Chapter 4

Social Proof

When people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate one another.

—Eric Hoffer

A few years ago, the managers of a chain of restaurants in Beijing, China, partnered with researchers to accomplish something decidedly profitable—increasing the purchase of certain menu items in a way that was effective yet costless. They wanted to see if they could get customers to choose them more frequently without lowering the items’ prices or using more expensive ingredients or hiring a chef who had more experience with the dishes or paying a consultant to write more enticing descriptions of them on the menu. They wanted to see if, instead, they could just give the dishes a label that would do the trick. Although they found a label that worked particularly well, they were surprised it wasn’t one they’d thought to use previously for this purpose, such as “Specialty of the house” or “Our chef’s recommendation for tonight.” Rather, the label merely described the menu items as the restaurant’s “most popular.”

The outcome was impressive. Sales of each dish jumped by an average of 13 to 20 percent. Quite simply, the dishes became more popular because of their popularity. Notably, the increase occurred through a persuasive practice that was costless, completely ethical (the items were indeed the most popular), easy to implement, and yet never before employed by the managers. Something similar happened in London when a local brewery with a pub on its premises agreed to try an experiment. The pub placed a sign on the bar stating, truthfully, that the brewery’s most popular beer that week was its porter. Porter sales doubled immediately. Click, run.

Results such as these make me wonder why other retailers don’t provide similar information. In ice-cream or frozen-yogurt shops, customers can often choose from an array of toppings for their order—chocolate bits or coconut flakes or cookie crumbles, and so on. Owing to the pull of the popular, you’d think managers would know to post signs describing the most frequently chosen topping or topping combination that month. But, they don’t. Too bad for them. Especially for customers who wouldn’t order a topping or who would order just one, true popularity information should result in more selections. For example, many McDonald’s restaurants offer a “McFlurry” dessert. When customers in one set of McDonald’s were told, “How about a dessert? The McFlurry is our visitors’ favorite,” McFlurry sales jumped 55 percent. Then, after a customer ordered a McFlurry, if the clerk said, “The [x] flavor is our visitors’ favorite McFlurry topping,” customers increased their extra topping purchases by an additional 48 percent.

EBOX 4.1

Although not all retailers understand how to harness popularity profitably, media giant Netflix learned that lesson from its own data and began operating on it immediately. According to technology and entertainment reporter Nicole LaPorte (2018), the company had “long prided itself on being highly secretive about things like watch-time and ratings, gleefully reveling in the fact that because Netflix doesn’t have to answer to advertisers, it doesn’t need to reveal any numbers.” But in an unexpected 2018 policy reversal, it began off-loading reams of information about its most successful offerings. As LaPorte put it, “In its letter to shareholders, Netflix rattled off titles and how many people had streamed them in a way that felt like a drunken sailor had taken over the normally heavily fortified battleship and was spilling trade secrets.”

Why? By then, company officials had seen that popularity precipitates popularity. Chief Product Officer Greg Peters disclosed the results of internal tests in which Netflix members who were told which shows were popular, then made them more so. Other company executives were quick on the uptake. Content head Ted Sarandros declared that going forward, Netflix would be more forthcoming “about what people are watching around the world.” Chairman and CEO Reed Hastings affirmed this promise, stating, “We’re just beginning to share that data. We’ll be leaning into that more quarter by quarter.”

Author’s note: These statements from Netflix executives tell us there are no dummies in leadership there. But one additional statement by Sarandros was most impressive to me: “Popularity is a data point that people can choose to use . . . We don’t want to suppress it if it’s helpful to members.” The key insight is that suppressing true popularity, as the company had done in the past, was unhelpful not only to its immediate profits but also to its subscribers’ prudent choices and resultant satisfaction—and, therefore, to the company’s long-term profits.

Social Proof

To discover why popularity is so effective, we need to understand the nature of yet another potent lever of influence: the principle of social proof. This principle states that we determine what is correct by finding out what other people think is correct. Importantly, the principle applies to the way we decide what constitutes correct behavior. We view an action as correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it. As a result, advertisers love to inform us when a product is the “fastest growing” or “largest selling” because they don’t have to convince us directly that their product is good; they need only show that many others think so, which often seems proof enough.

The tendency to see an action as appropriate when others are doing it works quite well normally. As a rule, we make fewer mistakes by acting in accord with social evidence than by acting contrary to it. Usually, when a lot of people are doing something, it is the right thing to do. This feature of the principle of social proof is simultaneously its major strength and major weakness. Like the other levers of influence, it provides a convenient shortcut for determining the way to behave, but at the same time, it makes one who uses the shortcut vulnerable to the attacks of profiteers who lie in wait along its path.

The problem comes when we begin responding to social proof in such a mindless and reflexive fashion we can be fooled by partial or fake evidence. Our folly is not that we use others’ behavior to help decide what to do in a situation; that is in keeping with the well-founded principle of social proof. The folly occurs when we do so automatically in response to counterfeit evidence provided by profiteers. Examples are plentiful. Certain nightclub owners manufacture a brand of visible social proof for their clubs’ quality by creating long waiting lines outside when there is plenty of room inside. Salespeople are taught to spice their pitches with invented accounts of numerous individuals who have purchased the product. Bartenders often salt their tip jars with a few dollar bills at the beginning of an evening to simulate tips left by prior customers. Church ushers sometimes salt collection baskets for the same reason and with the same positive effect on proceeds. Evangelical preachers are known to seed their audience with ringers, who are rehearsed to come forward at a specified time to give witness and donations. And, of course, product-rating websites are regularly infected with glowing reviews that manufacturers have faked or paid people to submit.1

People Power

Why are these profiteers so ready to use social proof for profit? They know our tendency to assume an action is more correct if others are doing it operates forcefully in a wide variety of settings. Sales and motivation consultant Cavett Robert captured the principle nicely in his advice to sales trainees: “Since 95 percent of the people are imitators and only 5 percent initiators, people are persuaded more by the actions of others than by any proof we can offer.” Evidence that we should believe him is everywhere. Let’s examine a small sample of it.

Morality: In one study, after being told that the majority of their peers favored the use of torture in interrogations, 80 percent of college students saw the practice as more morally acceptable. Criminality: Drinking and driving, parking in handicapped zones, retail theft, and hit-and-run violations (leaving the scene of a caused auto accident) become more likely if possible perpetrators believe the behavior is performed frequently by others. Problematic personal behavior: Men and women who believe that violence against an intimate partner is prevalent are more likely to engage in such violence themselves at a later time. Healthy eating: After learning that the majority of their peers try to eat fruit to be healthy, Dutch high school students increased fruit consumption by 35 percent—even though, in typical adolescent fashion, they had claimed no intention to change upon receiving the information. Online purchases: Although product testimonials are not new, the internet has changed the game by giving prospective customers ready access to the product ratings of numerous prior users; as a result, 98 percent of online shoppers say authentic customer reviews are the most important factor influencing their purchase decisions. Paying bills: When the city of Louisville, Kentucky, sent parking-ticket recipients a letter stating that the majority of such citations are paid within two weeks, payments increased by 130 percent, more than doubling parking-ticket revenue to the city. Science-based recommendations: During the COVID-19 outbreak of 2020, researchers examined the reasons Japanese citizens employed to decide how often to wear face masks, as urged by the country’s health scientists; although multiple reasons were measured—such as perceived severity of the disease, likelihood mask-wearing would protect oneself from infection, likelihood mask-wearing would protect others from infection—only one made a major difference in mask-wearing frequency: seeing other people wearing masks. Environmental action: Observers who perceive that many others are acting to preserve or protect the environment by recycling or conserving energy or saving water in their homes then act similarly.

In the arena of environmental action, social proof works on organizations too. Many governments expend significant resources regulating, monitoring, and sanctioning companies that pollute our air and water; these expenditures often appear wasted on some of the offenders who either flout the regulations altogether or are willing to pay fines that are smaller than the expense of compliance. But certain nations have developed cost-effective programs that work by firing up the (nonpolluting) engine of social proof. They initially rate the environmental performance of polluting firms within an industry and then publicize the ratings so all companies in that industry can see where they stand relative to their peers. The improvements have been dramatic—upwards of 30 percent—almost all of which have come from changes made by the relatively heavy polluters, who recognized how poorly they’d been doing compared with their contemporaries.

Researchers have also found that procedures based in social proof can work early in life—sometimes with astounding results. One psychologist in particular, Albert Bandura, led the way in developing such procedures to eliminate undesirable behavior. Bandura and his colleagues have shown how people suffering from phobias can be rid of these extreme fears in an amazingly simple fashion. For instance, in an initial study, nursery-school-aged children, chosen because they were terrified of dogs, merely watched a little boy playing happily with a dog for twenty minutes a day. This exhibition produced such marked changes in the reactions of the fearful children that after only four days, 67 percent of them were willing to climb into a playpen with a dog and remain confined there petting and scratching the dog while everyone else left the room. Moreover, when the researchers tested the children’s fear levels again, one month later, they found the improvement had not diminished during that time; in fact, the children were more willing than ever to interact with dogs.

An important practical discovery was made in a second study of children who were exceptionally afraid of dogs: To reduce the children’s fears, it was not necessary to provide live demonstrations of another child playing with a dog; film clips had the same impact. Tellingly, the most effective clips were those depicting multiple other children interacting with their dogs. The principle of social proof works best when the proof is provided by the actions of many other people. We’ll have more to say shortly about the amplifying role of “the many.”2

READER’S REPORT 4.1

From the director of recruitment and training at a Toyota dealership in Tulsa, Oklahoma

I work for the largest automotive retailer in Oklahoma. One of the biggest challenges we face is getting quality sales talent. We had seen poor return on our newspaper ads. So we decided to run our recruitment ads on radio during the after-work drive time. We ran an ad that focused on the great demand for our vehicles, how many people were buying them, and, consequently, how we needed to expand our sales force to keep up. As we hoped, we saw a significant jump in the number of applications to join our sales team.

But, the biggest effect we saw was an increase in customer floor traffic, an increase in sales in both the new and used vehicle departments, and a noticeable difference in the attitudes of our customers. The wildest thing was that the total number of sales increased by 41.7 percent over the previous January!!! We did almost one-and-a-half times the amount of business as the year before in an automotive market that was down by 4.4 percent. Of course, there could be other reasons for our success, such as a management change and a facilities update. But, still, whenever we run recruitment ads saying we need help to keep up with the demand for our vehicles, we see a significant increase in vehicle sales in those months.

Author’s note: So a reference to large consumer demand greatly affected customer attitude and actions toward the dealership’s cars and trucks. This is consistent with what we have already described in this chapter. But there’s something we haven’t yet described that helps account for the outsized effects the dealership witnessed. The high-demand information was “slipped into” an ad to recruit salespeople. Its notable success fits with evidence that people are more likely to be persuaded by information, including social-proof information, when they think it is not intended to persuade them (Bergquist, Nilsson, & Schultz, 2019; Howe, Carr, & Walton, in press). I am sure that, if the dealership’s ad had made a direct appeal for purchases—declaring, “People are buying our vehicles like crazy! Come get yours”—it would have been less effective.

After the Deluge

When it comes to illustrating the strength of social proof, one example is far and away my favorite. Several features account for its appeal: it offers a superb instance of the underused method of participant observation, in which a scientist studies a process by becoming immersed in its natural occurrence; it provides information of interest to such diverse groups as historians, psychologists, and theologians; and, most important, it shows how social evidence can be used on us—not by others but by ourselves—to assure us that what we prefer to be true will seem to be true.

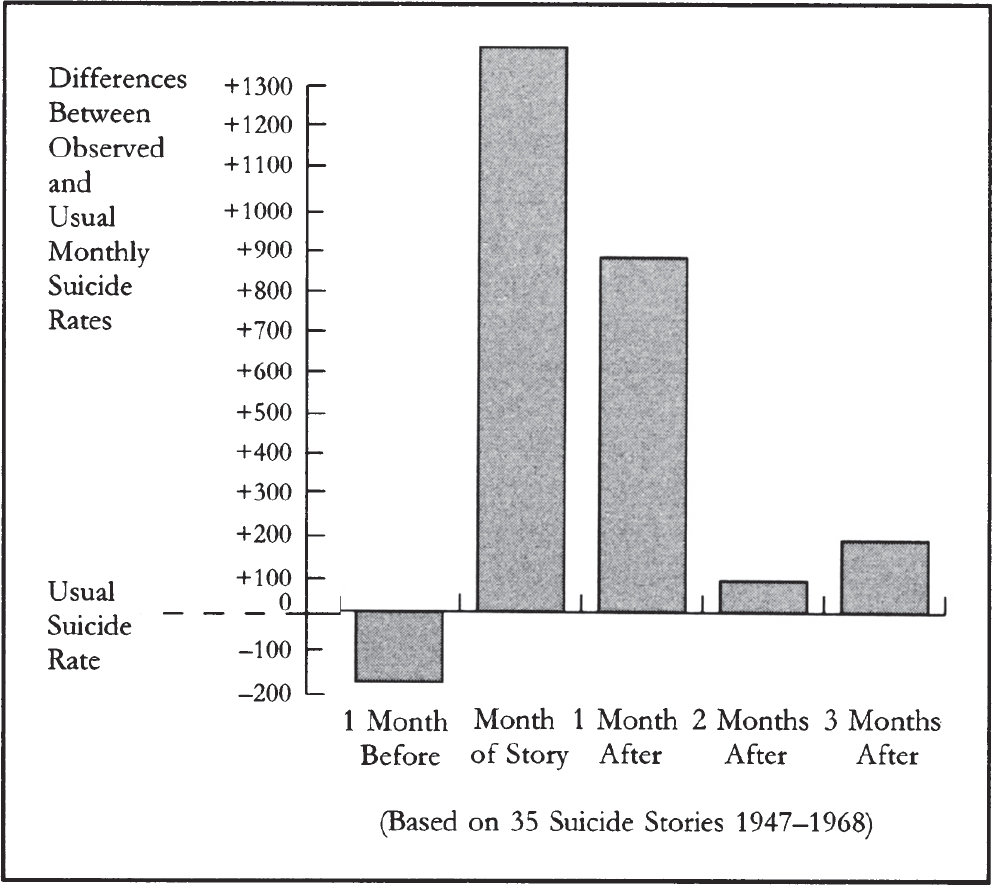

The story is an old one, requiring an examination of ancient data, for the past is dotted with end-of-the-world religious movements. Various sects and cults have prophesied that on a particular date there would arrive a period of redemption and great happiness for those who believed in the group’s teachings. In each case, it has been predicted that the beginning of a time of salvation would be marked by an important and undeniable event, usually the cataclysmic end of the world. Of course, these predictions have invariably proved false, to the acute dismay of the members of such groups.

However, immediately following the obvious failure of the prophecy, history records an enigmatic pattern. Rather than disbanding in disillusion, the cultists often become strengthened in their convictions. Risking the ridicule of the populace, they take to the streets, publicly asserting their dogma and seeking converts with a fervor that is intensified, not diminished, by the clear disconfirmation of a central belief. So it was with the Montanists of second-century Turkey, with the Anabaptists of sixteenth-century Holland, with the Sabbataists of seventeenth-century Izmir, and with the Millerites of nineteenth-century America. And, thought a trio of interested social scientists, so it might be with a doomsday cult based in twentieth-century Chicago. The scientists—Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schachter—who were then colleagues at the University of Minnesota, heard about the Chicago group and felt it worthy of close study. Their decision to investigate by joining the group, incognito, as new believers and by placing additional paid observers among its ranks resulted in a remarkably rich firsthand account of the goings-on before and after the day of predicted catastrophe, which they provided in their eminently readable book When Prophesy Fails.

The cult of believers was small, never numbering more than thirty members. Its leaders were a middle-aged man and woman, whom, for purposes of publication, the researchers renamed Dr. Thomas Armstrong and Mrs. Marian Keech. Dr. Armstrong, a physician on the staff of a college’s student-health service, had a long-held interest in mysticism, the occult, and flying saucers; as such, he served as a respected authority on these subjects for the group. Mrs. Keech, though, was the center of attention and activity. Earlier in the year, she had begun to receive messages from spiritual beings, whom she called the Guardians, located on other planets. It was these messages, flowing through Marian Keech’s hand via the device of “automatic writing,” that formed the bulk of the cult’s religious belief system. The teachings of the Guardians were a collection of New Age concepts, loosely linked to traditional Christian thought. It was as if the Guardians had read a copy of the Bible while visiting Northern California.

The transmissions from the Guardians, always the subject of much discussion and interpretation among the group, gained new significance when they began to foretell a great impending disaster—a flood that would begin in the Western Hemisphere and eventually engulf the world. Although the cultists were understandably alarmed at first, further messages assured them they, and all those who believed in the lessons sent through Mrs. Keech, would survive. Before the calamity, spacemen were to arrive and carry off the believers in flying saucers to a place of safety, presumably on another planet. Little detail was provided about the rescue except that the believers were to ready themselves for pickup by rehearsing certain passwords to be exchanged (“I left my hat at home.” “What is your question?” “I am my own porter.”) and by removing all metal from their clothes—because the wearing of metal made saucer travel “extremely dangerous.”

As the researchers observed the preparations during the weeks prior to the flood date, they noted with special interest two significant aspects of the members’ behavior. First, the level of commitment to the cult’s belief system was very high. In anticipation of their departure from doomed Earth, irrevocable steps were taken by the group members. Most incurred the opposition of family and friends to their beliefs but persisted, nonetheless, in their convictions, often when it meant losing the affections of these others. Several members were threatened by neighbors or family with legal actions designed to have them declared insane. Dr. Armstrong’s sister filed a motion to have his two younger children removed from his custody. Many believers quit their jobs or neglected their studies to devote all their time to the movement. Some gave or threw away their personal belongings, expecting them shortly to be of no use. These were people whose certainty they had the truth allowed them to withstand enormous social, economic, and legal pressures and whose commitment to their dogma grew as they resisted each pressure.

The second significant aspect of the believers’ preflood actions was a curious form of inaction. For individuals so clearly convinced of the validity of their creed, they did surprisingly little to spread the word. Although they initially publicized the news of the coming disaster, they made no attempt to seek converts, to proselytize actively. They were willing to sound the alarm and to counsel those who voluntarily responded to it, but that was all.

The group’s distaste for recruitment efforts was evident in various ways besides the lack of personal persuasion attempts. Secrecy was maintained in many matters—extra copies of the lessons were burned, passwords and secret signs were instituted, the contents of certain private tape recordings were not to be discussed with outsiders (so secret were the tapes that even longtime believers were prohibited from taking notes on them). Publicity was avoided. As the day of disaster approached, increasing numbers of newspaper, TV, and radio reporters converged on the group’s headquarters in Marian Keech’s house. For the most part, these people were turned away or ignored. The most frequent answer to their questions was, “No comment.”

Although discouraged for a time, the media representatives returned with a vengeance when Dr. Armstrong’s religious activities caused him to be fired from his post on the college health-service staff; one especially persistent newsman had to be threatened with a lawsuit. A similar siege was repelled on the eve of the flood when a swarm of reporters pushed and pestered the believers for information. Afterward, the researchers summarized the group’s preflood stance on public exposure and recruitment in respectful tones: “Exposed to a tremendous burst of publicity, they had made every attempt to dodge fame; given dozens of opportunities to proselyte, they had remained evasive and secretive and behaved with an almost superior indifference.”

Eventually, when all the reporters and would-be converts had been cleared from the house, the believers began making final preparations for the arrival of the spaceship scheduled for midnight that night. The scene as viewed by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter must have seemed like absurdist theater. Otherwise ordinary people—housewives, college students, a high school boy, a publisher, a physician, a hardware-store clerk and his mother—were participating earnestly in tragic comedy. They took direction from a pair of members who were periodically in touch with the Guardians; Marian Keech’s written messages were being supplemented that evening by “the Bertha,” a former beautician through whose tongue the “Creator” gave instruction. They rehearsed their lines diligently, calling out in chorus the responses to be made before entering the rescue saucer: “I am my own porter.” “I am my own pointer.” They discussed seriously whether the message from a caller identifying himself as Captain Video—a TV space character of the time—was properly interpreted as a prank or a coded communication from their rescuers.

In keeping with the admonition to carry nothing metallic aboard the saucer, the believers wore clothing from which all metal pieces had been torn out. The metal eyelets in their shoes had been ripped away. The women went braless or wore brassieres whose metal stays had been removed. The men had yanked the zippers out of their pants, which were supported by lengths of rope in place of belts.

The group’s fanaticism concerning the removal of all metal was vividly experienced by one of the researchers, who remarked, twenty-five minutes before midnight, that he had forgotten to extract the zipper from his trousers. As the observers tell it, “this knowledge produced a near panic reaction. He was rushed into the bedroom where Dr. Armstrong, his hands trembling and his eyes darting to the clock every few seconds, slashed out the zipper with a razor blade and wrenched its clasps free with wirecutters.” The hurried operation finished, the researcher was returned to the living room—a slightly less metallic but, one supposes, much paler man.

As the time appointed for their departure grew close, the believers settled into a lull of soundless anticipation. Fortunately, the trained scientists were able to provide a detailed account of the events that transpired during this momentous period.

The last ten minutes were tense ones for the group in the living room. They had nothing to do but sit and wait, their coats in their laps. In the tense silence two clocks ticked loudly, one about ten minutes faster than the other. When the faster of the two pointed to twelve-five, one of the observers remarked aloud on the fact. A chorus of people replied that midnight had not yet come. Bob Eastman affirmed that the slower clock was correct; he had set it himself only that afternoon. It showed only four minutes before midnight.

These four minutes passed in complete silence except for a single utterance. When the [slower] clock on the mantel showed only one minute remaining before the guide to the saucer was due, Marian exclaimed in a strained, high-pitched voice: “And not a plan has gone astray!” The clock chimed twelve, each stroke painfully clear in the expectant hush. The believers sat motionless.

One might have expected some visible reaction. Midnight had passed and nothing had happened. The cataclysm itself was less than seven hours away. But there was little to see in the reactions of the people in the room. There was no talking, no sound. People sat stock-still, their faces seemingly frozen and expressionless. Mark Post was the only person who even moved. He lay down on the sofa and closed his eyes but did not sleep. Later, when spoken to, he answered monosyllabically but otherwise lay immobile. The others showed nothing on the surface, although it became clear later that they had been hit hard. . . .

Gradually, painfully, an atmosphere of despair and confusion settled over the group. They reexamined the prediction and the accompanying messages. Dr. Armstrong and Mrs. Keech reiterated their faith. The believers mulled over their predicament and discarded explanation after explanation as unsatisfactory. At one point, toward 4 A.M., Mrs. Keech broke down and cried bitterly. She knew, she sobbed, that there were some who were beginning to doubt but that the group must beam light to those who needed it most and that the group must hold together. The rest of the believers were losing their composure, too. They were all visibly shaken and many were close to tears. It was now almost 4:30 A.M. and still no way of handling the disconfirmation had been found. By now, too, most of the group were talking openly about the failure of the escort to come at midnight. The group seemed near dissolution. (pp. 162–63, 168)

In the midst of gathering doubt, as cracks crawled through the believers’ confidence, the researchers witnessed a pair of remarkable incidents, one after another. The first occurred at about 4:45 a.m. when Marian Keech’s hand suddenly began transcribing through “automatic writing” the text of a holy message from above. When read aloud, the communication proved to be an elegant explanation for the events of that night. “The little group, sitting alone all night long, had spread so much light that God had saved the world from destruction.” Although neat and efficient, this explanation was not wholly satisfying by itself; for example, after hearing it, one member simply rose, put on his hat and coat, and left, never to return. Something additional was needed to restore the believers to their previous levels of faith.

It was at this point that the second notable incident occurred to supply that need. Once again, the words of those who were present offer a vivid description:

The atmosphere in the group changed abruptly and so did their behavior. Within minutes after she had read the message explaining the disconfirmation, Mrs. Keech received another message instructing her to publicize the explanation. She reached for the telephone and began dialing the number of a newspaper. While she was waiting to be connected, someone asked: “Marian, is this the first time you have called the newspaper yourself?” Her reply was immediate: “Oh yes, this is the first time I have ever called them. I have never had anything to tell them before, but now I feel it is urgent.” The whole group could have echoed her feelings, for they all felt a sense of urgency. As soon as Marian had finished her call, the other members took turns telephoning newspapers, wire services, radio stations, and national magazines to spread the explanation of the failure of the flood. In their desire to spread the word quickly and resoundingly, the believers now opened for public attention matters that had been thus far utterly secret. Where only hours earlier they had shunned newspaper reporters and felt that the attention they were getting in the press was painful, they now became avid seekers for publicity. (p. 170)

Not only had the long-standing policies concerning secrecy and publicity done an about-face, but so, too, had the group’s attitude toward potential converts. Whereas likely recruits who previously visited the house had been mostly ignored, turned away, or treated with casual attention, the day following the disconfirmation saw a different story. All callers were admitted, all questions were answered, all visitors were proselytized. The members’ unprecedented willingness to accommodate new recruits was perhaps best demonstrated when nine high school students arrived on the following night to speak with Mrs. Keech.

They found her at the telephone deep in a discussion of flying saucers with a caller whom, it later turned out, she believed to be a spaceman. Eager to continue talking to him and at the same time anxious to keep her new guests, Marian simply included them in the conversation and, for more than an hour, chatted alternately with her guests in the living room and the “spaceman” on the other end of the telephone. So intent was she on proselyting that she seemed unable to let any opportunity go by. (p. 178)

To what can we attribute the believers’ radical turnabout? Within a few hours, they had moved from clannish and taciturn hoarders of the Word to expansive and eager disseminators of it. What could have possessed them to choose such an ill-timed instant—when the failure of the flood was likely to cause nonbelievers to view the group and its dogma as laughable?

The crucial event occurred sometime during “the night of the flood” when it became increasingly clear the prophecy would not be fulfilled. Oddly, it was not their prior certainty that drove the members to propagate the faith, it was an encroaching sense of uncertainty. It was the dawning realization that if the spaceship and flood predictions were wrong, so might be the entire belief system on which they rested. For those huddled in Marian Keech’s living room, that growing possibility must have seemed hideous.

The group members had gone too far, given up too much for their beliefs to see them destroyed; the shame, the economic cost, the mockery would be too great to bear. The overarching need of the cultists to cling to those beliefs seeps poignantly from their own words. From a young woman with a three-year-old child:

I have to believe the flood is coming on the twenty-first because I’ve spent all my money. I quit my job, I quit computer school. . . . I have to believe. (p. 168)

From Dr. Armstrong to one of the researchers four hours after the failure of the saucermen to arrive:

I’ve had to go a long way. I’ve given up just about everything. I’ve cut every tie. I’ve burned every bridge. I’ve turned my back on the world. I can’t afford to doubt. I have to believe. And there isn’t any other truth. (p. 168)

Imagine the corner in which Dr. Armstrong and his followers found themselves as morning approached. So massive was the commitment to their beliefs that no other truth was tolerable. Yet those beliefs had taken a merciless pounding from physical reality: No saucer had landed, no spacemen had knocked, no flood had come, nothing had happened as prophesied. Because the only acceptable form of truth had been undercut by physical proof, there was but one way out of the corner for the group. It had to create another type of proof for the truth of its beliefs: social proof.

This, then, explains the group members’ sudden shift from secretive conspirators to zealous missionaries. It also explains the curious timing of the shift—precisely when a direct disconfirmation of their beliefs had rendered them least convincing to outsiders. It was necessary to risk the scorn and derision of nonbelievers because publicity and recruitment efforts provided the only remaining hope. If they could spread the Word, if they could inform the uninformed, if they could persuade the skeptics, and if, by so doing, they could win new converts, their threatened but treasured beliefs would become truer. The principle of social proof says so: The greater the number of people who find any idea correct, the more a given individual will perceive the idea to be correct. The group’s assignment was clear; because the physical evidence could not be changed, the social evidence had to be. Convince, and ye shall be convinced.3

Optimizers

All the levers of influence discussed in this book work better under some conditions than others. If we are to defend ourselves adequately against any such lever, it is vital that we know its optimal operating conditions in order to recognize when we are most vulnerable to its influence. In the case of social proof, there are three main optimizing conditions: when we are unsure of what is best to do (uncertainty); when the evidence of what is best to do comes from numerous others (the many); and when that evidence comes from people like us (similarity).

Uncertainty: In Its Throes, Conformity Grows

We have already had a hint of when the principle of social proof worked best with the Chicago believers. It was when a sense of shaken confidence triggered their craving for converts, for new believers who could validate the truth of the original believers’ views. In general, when we are unsure of ourselves, when the situation is unclear or ambiguous, when uncertainty reigns, we are most likely to accept the actions of others—because those actions reduce our uncertainty about what is correct behavior there.

One way uncertainty develops is through lack of familiarity with the situation. Under such circumstances, people are especially likely to follow the lead of others. Remember this chapter’s account of restaurant managers in Beijing who greatly increased customers’ purchases of certain dishes on the menu by describing them as most popular? Although the labeled popularity of an item elevated its choice by all sorts of diners (males, females, customers of any age), there was one kind of customer that was most likely to choose based on popularity—those who were infrequent and, therefore, unfamiliar visitors. Customers who weren’t in a position to rely on existing experience in the situation had the strongest tendency to resort to social proof.

Consider how this simple insight made one man a multimillionaire. His name was Sylvan Goldman and, after acquiring several small grocery stores in 1934, he noticed his customers stopped buying when their handheld shopping baskets got too heavy. This inspired him to invent the shopping cart, which in its earliest form was a folding chair equipped with wheels and a pair of heavy metal baskets. The contraption was so unfamiliar-looking that, at first, none of Goldman’s customers used one—even after he built a more-than-adequate supply, placed several in a prominent place in the store, and erected signs describing their uses and benefits. Frustrated and about to give up, he tried one more idea to reduce his customers’ uncertainty, one based on social proof. He hired shoppers to wheel the carts through the store. His true customers soon began following suit, his invention swept the nation, and he died a wealthy man with an estate of over $400 million.4

READER’S REPORT 4.2

From a Danish university student

While in London visiting my girlfriend, I was sitting in an Underground station on a stopped train. The train failed to depart on time, and there was no announcement as to the cause. On the opposite side of the platform, another train had stopped too. Then, a strange thing happened. A few people started leaving my train and boarding the other one, which sparked a self-feeding, self-amplifying reaction, making everybody (about 200 people, including me) disembark my train and board the other. Then, after several minutes, something even more peculiar happened: A few people started leaving the second train, and the whole mechanism was produced again in the reverse order, making everybody (including me, once again) go back to the original train, still without any announcement to justify the retreat.

Needless to say, it left me with a rather silly feeling of being a mindless turkey following every collective impulse of social proof.

Author’s note: In addition to a lack of familiarity, a lack of objective cues of correctness in a situation generates feelings of uncertainty. For example, in this situation, there were no announcements. Consequently, social proof took over to guide behavior, no matter how farcically. Click, run (back and forth).

In the process of trying to resolve our uncertainty by examining the reactions of other people, we are likely to overlook a subtle, but important fact: especially in an ambiguous situation, those people are probably examining the social evidence too. This tendency for everyone to be looking to see what everyone else is doing can lead to a fascinating phenomenon called pluralistic ignorance. A thorough understanding of the phenomenon helps explain a troubling occurrence: the failure of bystanders to aid victims in agonizing need of help.

The classic report of such bystander inaction and the one that has produced the most debate in journalistic, political, and scientific circles began as an article in the New York Times: a woman in her late twenties, Kitty Genovese, was killed in a late-night attack while thirty-eight of her neighbors watched from their apartment windows without lifting a finger to help. News of the killing created a national uproar and led to a line of scientific research investigating when bystanders will and will not help in an emergency. More recently, the details of the neighbors’ inaction—and even whether it had actually occurred—has been debunked by researchers who uncovered shoddy journalistic methods in this specific case. Nonetheless, because such events continue to arise, the question of when bystanders will intervene in an emergency remains important. One answer involves the potentially tragic consequences of the pluralistic-ignorance effect, which are starkly illustrated in a UPI news release from Chicago:

A university coed was beaten and strangled in daylight hours near one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city, police said Saturday.

The nude body of Lee Alexis Wilson, 23, was found Friday in dense shrubbery alongside the wall of the Art Institute by a 12-year-old boy playing in the bushes.

Police theorized she may have been sitting or standing by a fountain in the Art Institute’s south plaza when she was attacked. The assailant apparently then dragged her into the bushes. She apparently was sexually assaulted, police said.

Police said thousands of persons must have passed the site and one man told them he heard a scream about 2 p.m. but did not investigate because no one else seemed to be paying attention (emphasis added).

Often an emergency is not obviously an emergency. Is the man lying in the alley a heart-attack victim or a drunk sleeping one off? Is the commotion next door an assault requiring the police or an especially loud marital spat where intervention would be inappropriate and unwelcome? What is going on? In times of such uncertainty, the natural tendency is to look around at the actions of others for clues. From the principle of social proof, we can determine from the way the other witnesses are reacting whether the event is or is not an emergency.

What is easy to forget, though, is that everybody else observing the event is likely to be looking for social evidence to reduce their uncertainty. Because we all prefer to appear poised and unflustered among others, we are likely to search for that evidence placidly, with brief, camouflaged glances at those around us. Therefore, everyone is likely to see everyone else looking unruffled and failing to act. As a result, and by the principle of social proof, the event will be roundly interpreted as a nonemergency.

A Scientific Summary

Social scientists have a good idea of when bystanders will offer emergency aid. First, once uncertainty is removed and witnesses are convinced an emergency situation exists, aid is very likely. Under these conditions, the number of bystanders who either intervene themselves or summon help is quite comforting. For example, in four separate experiments done in Florida, accident scenes involving a maintenance man were staged. When it was clear that the man was hurt and required assistance, he was helped 100 percent of the time in two of the experiments. In the other two experiments, where helping involved contact with potentially dangerous electric wires, the victim still received bystander aid in 90 percent of the instances. The situation becomes very different when, as in many cases, bystanders cannot be sure the event is an emergency.

Devictimizing Yourself

Explaining the dangers of modern life in scientific terms does not dispel them. Fortunately, our current understanding of the bystander-intervention process offers real hope. Armed with scientific knowledge, an emergency victim can increase markedly the chances of receiving aid from others. The key is the realization that groups of bystanders fail to help because the bystanders are unsure rather than unkind. They don’t help because they are unsure an emergency actually exists and whether they are responsible for taking action. When they are confident of their responsibilities for intervening in a clear emergency, people are exceedingly responsive.

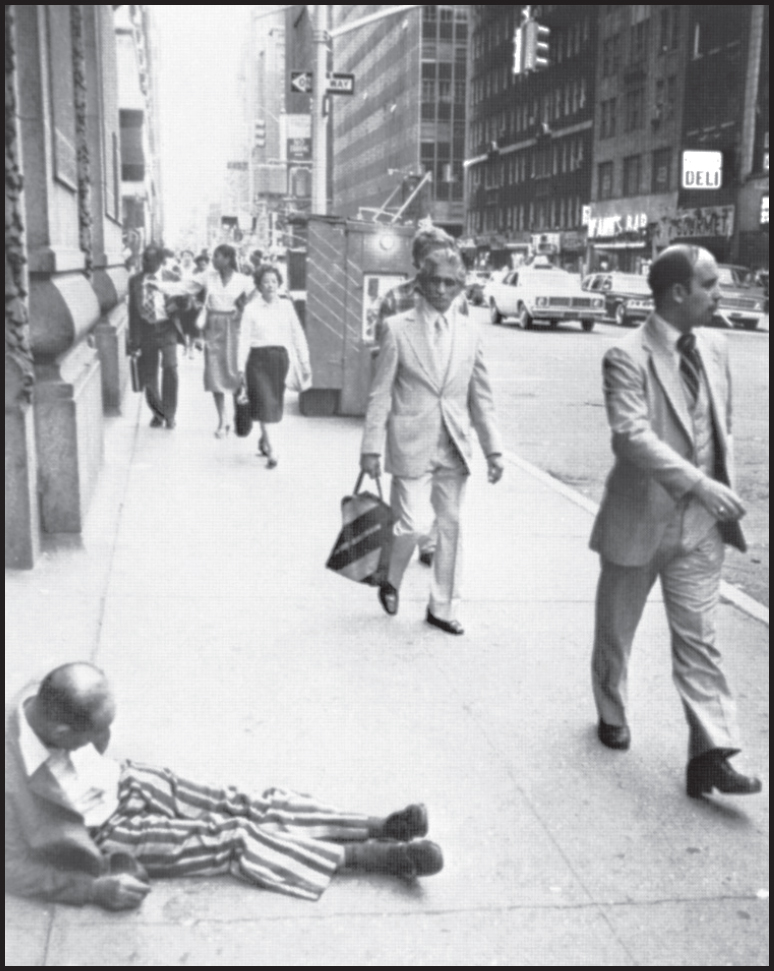

Figure 4.1: Victim?

At times like this one, when the need for emergency aid is unclear, even genuine victims are unlikely to be helped in a crowd. Think how, if you were a second passerby in this situation, you might be influenced by the first passerby to believe that no aid was called for.

Jan Halaska, Photo Researchers, Inc.

Once it is understood that the enemy is the state of uncertainty, it becomes possible for emergency victims to reduce this uncertainty, thereby protecting themselves. Imagine, for example, you are spending a summer afternoon at a music concert in a park. As the concert ends and people begin leaving, you notice a slight numbness in one arm but dismiss it as nothing to be alarmed about. Yet, while moving with the crowd to the distant parking areas, you feel the numbness spreading down to your hand and up one side of your face. Feeling disoriented, you sit against a tree for a moment to rest. Soon you realize something is drastically wrong.

Sitting down has not helped; in fact, control of your muscles has worsened, and you are having difficulty moving your mouth and tongue to speak. You try to get up but can’t. A terrifying thought rushes to mind: “Oh, God, I’m having a stroke!” People are streaming by without paying attention. The few who notice the odd way you are slumped against the tree or the strange look on your face check the social evidence around them and, seeing no one reacting with concern, walk on convinced that nothing is wrong, leaving you terrified and on your own.

Were you to find yourself in such a predicament, what could you do to overcome the odds against receiving help? Because your physical abilities would be deteriorating, time would be crucial. If, before you could summon aid, you lost your speech or mobility or consciousness, your chances for assistance and for recovery would plunge drastically. It would be essential to request help quickly. What would be the most effective form of that request? Moans, groans, or outcries probably would not do. They might bring you some attention, but they would not provide enough information to assure passersby a true emergency existed.

If mere outcries are unlikely to produce help from the passing crowd, perhaps you should be more specific. Indeed, you need to do more than try to gain attention; you should call out clearly your need for assistance. You must not allow bystanders to define your situation as a nonemergency. Use the word “Help” to show your need for emergency aid, and don’t worry about being wrong. Embarrassment in such a situation is a villain to be crushed. If you think you are having a stroke, you cannot afford to be worried about the possibility of overestimating your problem. The difference is that between a moment of embarrassment and possible death or lifelong paralysis.

Even a resounding call for help is not your most effective tactic. Although it may reduce bystanders’ doubts that a real emergency exists, it will not remove several other important uncertainties within each onlooker’s mind: What kind of aid is required? Should I be the one to provide the aid, or should someone more qualified do it? Has someone else already acted to get professional help, or is it my responsibility? While the bystanders stand gawking at you and grappling with these questions, time vital to your survival could he slipping away.

Clearly, then, as a victim you must do more than alert bystanders to your need for emergency assistance; you must also remove their uncertainties about how that assistance should be provided and who should provide it. What would be the most efficient and reliable way to do so? Based on research findings, my advice would be to focus on one individual in the crowd, then stare at, speak to, and point directly at that person and no one else: “You, sir, in the blue jacket, I need help. Call 911 for an ambulance.” With that one utterance, you would dispel all the uncertainties that might prevent or delay help. With that one statement you will have put the man in the blue jacket in the role of “rescuer.” He should now understand that emergency aid is needed; he should understand that he, not someone else, is responsible for providing the aid; and, finally, he should understand exactly how to provide it. All the scientific evidence indicates the result should be quick, effective assistance.

READER’S REPORT 4.3

From a woman living in Wrocław, Poland

I was going through a well-lighted road crossing when I thought I saw somebody fall into a ditch left by workers. The ditch was well protected, and I was not sure if I really saw it—maybe it was just imagination. One year ago, I would continue on my way, believing that the people passing by who had been closer saw better. But I had read your book. So, I stopped and returned to check if it was true. And it was. A man fell into this hole and was lying there shocked. The ditch was quite deep, so people walking nearby couldn’t see anything. When I tried to do something, two guys walking on this street stopped to help me pull the man out.

Today, the newspapers wrote that during the last three weeks of winter, 120 people died in Poland, frozen. This guy could have been 121—that night the temperature was –21C.

He should be grateful to your book that he is alive.

Author’s note: Several years ago, I was involved in a rather serious automobile accident that occurred at an intersection. Both I and the other driver were hurt: he was slumped, unconscious, over his steering wheel while I had staggered, bloody, from behind mine. Cars began to roll slowly past us; their drivers gawked but did not stop. Like the Polish woman, I, too, had read the book, so I knew what to do. I pointed directly at the driver of one car and said, “Call the police.” To a second and third driver, I said, “Pull over, we need help.” Their aid was not only rapid but infectious. More drivers began stopping—spontaneously—to tend to the other victim. The principle of social proof was working for us now. The trick had been to get the ball rolling in the direction of help. Once that was accomplished, social proof’s natural momentum did the rest.

In general, then, your best strategy when in need of emergency help is to reduce the uncertainties of those around you concerning your condition and their responsibilities. Be as precise as possible about your need for aid. Do not allow bystanders to come to their own conclusions because the principle of social proof and the consequent pluralistic-ignorance effect might well cause them to view your situation as a nonemergency. Of all the techniques in this book designed to produce compliance with a request, this one is the most important to remember. After all, the failure of your request for emergency aid could mean the loss of your life.

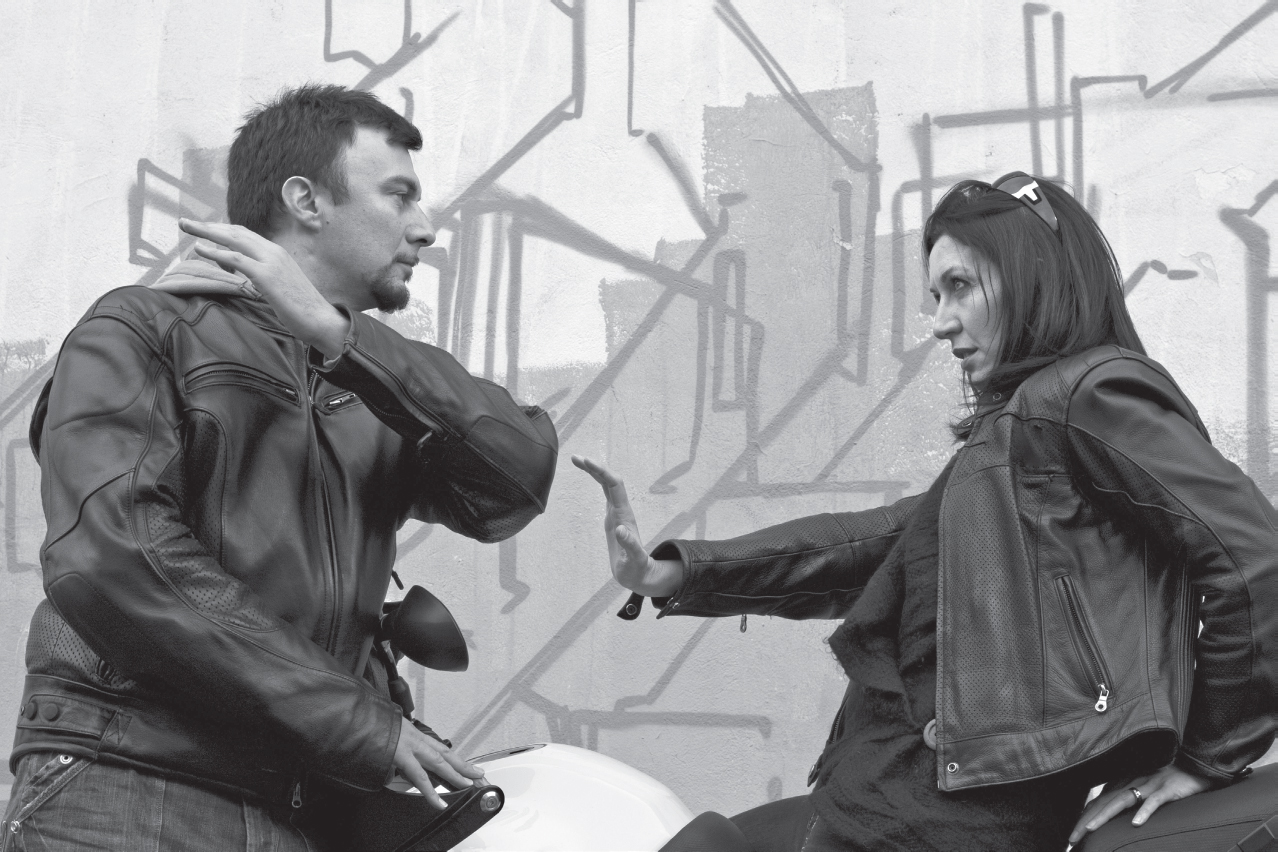

Besides this broad advice, there is a singular form of uncertainty for women that they need to dispel in a unique emergency situation for them—a public confrontation in which a woman is being physically attacked by a man. Concerned researchers suspected witnesses to such confrontations may not help because they are uncertain about the nature of the pair’s relationship, thinking intervention might be unwelcome in a lovers’ quarrel. To test this possibility, the researchers exposed subjects to a staged public fight between a man and a woman. When there were no cues as to the sort of relationship between the two, the great majority of male and female subjects (nearly 70 percent) assumed that the two were romantically involved; only 4 percent thought they were complete strangers. In other experiments where there were cues that defined the combatants’ relationship—the woman shouted either “I don’t know why I ever married you” or “I don’t know you”—the studies uncovered an ominous reaction on the part of bystanders. Although the severity of the fight was identical, observers were less willing to help the married woman because they thought it was a private matter in which their intervention would be unwanted and embarrassing to all concerned.

Figure 4.2: To get help, you must shout correctly.

Observers of male–female confrontations often assume the pair is romantically involved and that intervention would be unwanted or inappropriate. To combat this perception and get aid, the woman should shout, “I don’t know you.”

Tatagatta/Fotolia

Thus, a woman caught in a physical confrontation with a man, any man, should not expect to get bystander aid simply by shouting for relief. Observers are likely to define the event as a domestic squabble and, with that definition in place, may well assume that helping would be socially inappropriate. Fortunately, the researchers’ data suggest a way to overcome this problem: by loudly labeling her attacker a stranger—“I don’t know you!”—a woman should greatly increase her chances for receiving assistance.5

The Many: The More We See, the More There Will Be

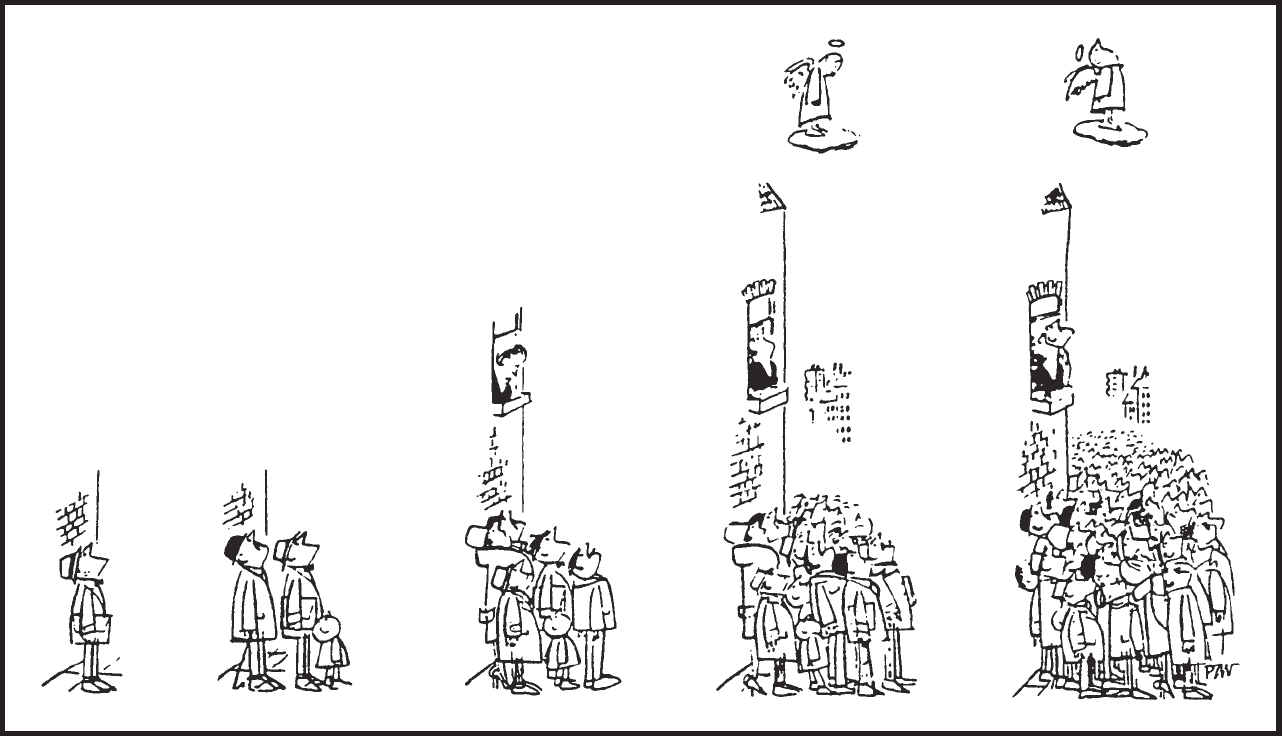

A bit earlier I stated that the principle of social proof, like all other levers of influence, works better under some conditions than others. We have already explored one of those conditions: uncertainty. For sure, when people are unsure, they are more likely to use others’ actions to decide how they themselves should act. In addition, there is another important optimizing condition: the many. Any reader who doubts that the seeming appropriateness of an action is importantly influenced by the number of others performing it might try a small experiment. Stand on a busy sidewalk, pick an empty spot in the sky or on a tall building, and stare at it for a full minute. Very little will happen around you during that time—most people will walk past without glancing up, and virtually no one will stop to stare with you. Now, on the next day, go to the same place and bring along some friends to look upward too. Within sixty seconds, a crowd will have stopped to crane their necks skyward with the group. For those passersby who do not join you, the pressure to look up at least briefly will be nearly irresistible; if the results of your experiment are like those of one performed by researchers in New York City, you and your friends will cause 80 percent of all passersby to lift their gaze to your empty spot. Moreover, up to a point (around twenty people), the more friends you bring along, the more passersby will join in.

Social-proof information doesn’t have to be only visual to sweep people in its direction. Consider the heavy-handed exploitation of the principle within the history of grand opera, one of our most venerable art forms. There is a phenomenon called claquing, said to have begun in 1820 by a pair of Paris opera-house habitués named Sauton and Porcher. The men were more than operagoers, though. They were businessmen whose product was applause; and they knew how to structure social proof to incite it.

Figure 4.3: “Looking for Higher (and Higher) Meaning”

The draw of the many is devilishly strong.

© Punch/Rothco

Organizing their business under the title l’Assurance des succès dramatiques, they leased themselves and their employees to singers and opera managers who wished to be assured of an appreciative audience response. So effective were Sauton and Porcher in stimulating genuine audience reaction with their rigged reactions that, before long, claques (usually consisting of a leader—chef de claque—and several individual claqueurs) had become an established and persistent tradition throughout the world of opera. As music historian Robert Sabin (1964) notes, “By 1830 the claque was a full-bloom institution, collecting by day, applauding by night . . . But it is altogether probable that neither Sauton, nor his ally Porcher, had a notion of the extent to which their scheme of paid applause would be adopted and applied wherever opera is sung.”

As claquing grew and developed, its practitioners offered an array of styles and strengths—the pleureuse, chosen for her ability to weep on cue; the bisseur, who called “bis” (repeat) and “encore” in ecstatic tones; and the rieur, selected for the infectious quality of his laugh. For our purposes, though, the most instructive parallel to modern forms can be observed in the business model of Sauton and Porcher and their successors: They charged by the staffer, recognizing that the more claqueurs they sent to be scattered among an audience, the greater would be the persuasive impression that many others liked the performance. Claque, run.

Operagoers are hardly alone in this respect. Present-day observers of political events, such as US presidential debates, can be significantly affected by the magnitude of audience reaction. Candidates’ perceived performances in US presidential debates have been of no small significance in election outcomes, as political scholars have noted their critical impact. For this reason, researchers have investigated the factors that have led to debate success and failure. One of those factors has been how the responses of audiences attending a debate have affected the responses of those observing remotely, usually on TV but also on radio and streaming video. By presenting the candidates’ true performances but technologically modifying the responses (applause, cheering, laughing) of on-site audiences, researchers have examined the influence of these altered responses on remote audiences’ views of the candidates. Their findings were consistent: in a 1984 Ronald Reagan–Walter Mondale debate, a 1992 Bill Clinton–George Bush debate, and a 2016 Donald Trump–Hillary Clinton debate, whichever candidate seemingly received the strongest response from the on-site audience won the day with the remote audiences, in terms of debate performance, leadership qualities, and likability. Certain researchers have become concerned with a tendency in presidential debates for candidates to seed the on-site debate audiences with raucously loud followers whose effusive responses give the impression of greater-than-actual support in the room. The practice of claquing is far from dead.6

READER’S REPORT 4.4

From a Central American marketing executive

As I read the chapter about social proof, I recognized an interesting local example. In my country, Ecuador, you can hire a person or groups of people (traditionally consisting of women) to come to the funeral of a family member or friend. The job of these people is to cry while the dead person is being buried, making, for sure, more people start to cry. This job was quite popular a few years ago, and the well-known people that worked in this job received the name of “lloronas,” which means criers.

Author’s note: We can see how, at different times and in different cultures, it has been possible to profit from manufactured social proof. In today’s TV sitcoms, we no longer have claqueurs and rieurs to fool us into laughing longer and harder. Instead, we have “laugh-trackers” and “sweeteners”—audio technicians whose job is to enhance the laughter of studio audiences to make the programs’ comic material seem funnier to their true targets: TV viewers such as you and me. Sad to say, we are likely to fall for their tricks. Experiments show that the use of fabricated merriment leads audiences to laugh more frequently and longer, as well as to rate humorous material funnier (Provine, 2000).7

Why Does “The Many” Work So Well?

A few years ago, a shopping mall in Essex, England, had a problem. During normal lunch hours, its food court became so congested that customers encountered long waits and a shortage of tables for their meals. For help, mall managers turned to a team of researchers who set up a study that provided a simple solution based on the psychological pull of “the many.” The solution also incorporated all three of the reasons why this optimizer of social proof works so forcefully: validity, feasibility, and social acceptance.

The study itself was straightforward. The researchers created two posters urging mall visitors to enjoy an early lunch at the food court. One poster included an image of a single person doing so; the other poster was identical, except the image was of several such visitors. Reminding customers of the opportunity for an early lunch (as the first poster did) proved successful, producing a 25 percent increase in customer activity in the food court before noon. But the real success came from the second poster, which lifted prenoon consumer activity by 75 percent.

VALIDITY

Following the advice or behaviors of the majority of those around us is often seen as a shortcut to good decision-making. We use the actions of others as a way to locate and validate a correct choice. If everybody’s raving about a new restaurant, it’s probably a good one that we’d like too. If the great majority of online reviewers is recommending a product, we’ll likely feel more confident clicking the purchase button. In the shopping-mall posters example, it appears that visitors exposed to a photo of multiple others taking a prenoon lunch were particularly swayed to view the idea as a good one. Additional studies have shown that ads presenting increasingly larger percentages of customers favoring a brand (“4 out of 7” versus “5 out of 7” versus “6 out of 7”) get increasingly more observers to prefer the brand; moreover, this is the case because observers assume that the brand with the largest percentage of customers preferring it must be the right choice.

Often no complex cognitive operations are necessary for others’ choices to establish validity; the process can be more automatic than that. For example, fruit flies possess no complex cognitive capacities. Yet when female fruit flies viewed other females mating with a male that had been colored a particular tint (pink or green) by researchers, they became much more willing to choose a mate of the same color—70 percent of the time. It’s not just fruit flies that respond to social proof without cognitive direction. Consider the admission of prominent travel writer Doug Lansky who, while visiting England’s Royal Ascot Races, caught a glimpse of the British Royal Family and readied his camera for a photo. “I got the Queen in focus, with Prince Charles and Prince Philip sitting beside her. Suddenly, it hit me: Why did I even want this picture? It’s not like there’s a world shortage of Royal Family photos. No tabloids were going to pay me big money for the shot. I was no paparazzi. But, shutters firing around me like Uzis, I joined in the frenzy. I couldn’t help myself.” Click, run . . . click, click, click.

Let’s stay in England for an enlightening historical illustration of the power of “the many” to validate a choice and initiate contagious effects. For centuries, people have been subject to irrational sprees, manias, and panics of various sorts. In his classic text, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Charles MacKay listed hundreds that occurred before the book’s first publication in 1841. Most shared an instructive characteristic—contagiousness. Others’ actions spread to observers, who then acted similarly and thereby validated the correctness of the action for still other observers, who acted similarly in turn.

In 1761, London experienced two moderate-sized earthquakes exactly a month apart. Convinced by this coincidence that a third, much larger quake would occur on the same date a month later, a soldier named Bell began spreading his prediction that the city would be destroyed on the fifth of April. At first, scant few paid him any heed. But those who did took the precaution of moving their families and possessions to surrounding areas. The sight of this small exodus stirred others to follow, which, in cascading waves over the next week, led to near panic and a large-scale evacuation. Great numbers of Londoners streamed into nearby villages, paying outrageous prices for any accommodations. Included in the terrified throngs were many who, according to MacKay, “had laughed at the prediction a week before, [but who] packed up their goods, when they saw others doing so, and hastened away.”

After the designated day dawned and died without a tremor, the fugitives returned to the city furious at Mr. Bell for leading them astray. As MacKay’s description makes clear, their anger was misdirected. It wasn’t the crackpot Bell who was most convincing. It was the Londoners themselves who validated his theory, each to the other.8

EBOX 4.2

We don’t have to rely on events from eighteenth-century England for examples of baseless, social proof–fueled panics. Indeed, owing to particular internet features and capacities, we are now seeing instances sprouting like weeds all around us.

In late 2019 and early 2020, alarming rumors went viral that claimed men in white vans were abducting women for purposes of sex trafficking and selling their body parts. Propelled by the social-media giant Facebook’s algorithms giving prominence to posts that are widely shared or trending, the tale, which began in Baltimore, spread in snowballing fashion around the United States and beyond. As a consequence, white van owners in multiple cities reported being threatened and harassed by residents after the rumor began circulating in their communities. One workman lost jobs after being targeted in a Facebook post. Another was shot to death by two men reacting to a false claim of an attempted abduction. This, even though authorities have never found a single actual incident.

No matter. For instance, the mayor of Baltimore, Bernard Young, was sufficiently moved by the story to issue an unnerving televised warning to the women of his city: “Don’t park near a white van. Make sure you keep your cellphone in case somebody tries to abduct you.” What was Mayor Young’s evidence for the threat? It was nothing that came from his own police.

Instead, he said, “It was all over Facebook.”

Author’s note: It’s telling that perceived validity of the rumor developed from unfounded fears, rendered contagious by the algorithms of a frequently checked social-media feed. “Truth” was established without physical proof; there was only social proof. That was enough, as it often is.

There’s an age-old truism that makes this point: “If one person says you have a tail, you laugh it off as stupid; but, if three people say it, you turn around.”

FEASIBILITY

If we see a lot of other people doing something, it doesn’t just mean it’s probably a good idea. It also means we could probably do it too. Within the British shopping-mall study, the visitors seeing a poster of multiple others taking an early lunch might well have said to themselves something like, “Well, this idea seems doable. I guess it’s not a big deal to arrange shopping plans or work hours to have an early lunch.” Thus, besides perceived validity, a second reason “the many” is effective is that it communicates feasibility: if lots can do it, it must not be difficult to pull off. A study of residents of several Italian cities found that if residents believed many of their neighbors recycled in the home, then they were more willing to recycle themselves, in part, because they saw recycling as less difficult to manage.

With a set of estimable colleagues leading the way, I once did a study to see what we could best say to influence people to conserve household energy. We delivered one of four messages to their homes, once a week for a month, asking them to reduce their energy consumption. Three of the messages contained a frequently employed reason for conserving energy—“The environment will benefit”; “It’s the socially responsible thing to do”; or “It will save you significant money on your next power bill”—whereas the fourth played the social-proof card, stating (honestly), “Most of your fellow community residents do try to conserve energy at home.” At the end of the month, we recorded how much energy was used and learned that the social proof–based message had generated 3.5 times as much energy savings as any of the other messages. The size of the difference surprised almost everyone associated with the study—me, for one, but also my fellow researchers and even a sample of other homeowners. The homeowners, in fact, expected that the social-proof message would be least effective.

When I report on this research to utility-company officials, they frequently don’t trust it because of an entrenched belief that the strongest motivator of human action is economic self-interest. They say, “C’mon, how are we supposed to believe that telling people their neighbors are conserving is three times more effective than telling them they can cut their power bills significantly?” Although there are various possible responses to this legitimate question, there’s one that’s nearly always proved persuasive for me. It involves the second reason, in addition to validity, that social-proof information works so well—feasibility. If I inform homeowners that by saving energy, they could also save a lot of money, it doesn’t mean they would be able to make it happen. After all, I could reduce my next power bill to zero if I turned off all the electricity in my house and coiled up on the floor in the dark for a month, but that’s not something I’d reasonably be able to do. A great strength of “the many” is that it destroys the problem of uncertain achievability. If people learn that many others around them are conserving energy, there is little doubt as to its feasibility. It comes to seem realistic and, therefore, actionable.9

SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE

We feel more socially accepted being one of the many. It’s easy to see why. Think again of the British shopping-mall study. Visitors either encountered a poster showing a single shopper taking an early lunch in the mall’s food court or multiple shoppers doing so. To follow the example of the first poster, observers risked the social disapproval of being viewed as a loner or oddball or outsider. The opposite was true of following the example of the second poster, which assured observers of the personal comfort of being among the many. The emotional difference between those two experiences is significant. Compared to holding an opinion that fits with the group’s, holding an opinion that is out of line creates psychological distress.

In one study, research participants were hooked up to a brain scanner while they received information from others that conflicted with their own opinions. The conflicting information came either from four other participants or from four computers. Conformity was greater when the conflicting information came from the set of persons than from the set of computers, even though participants rated the two kinds of judgments as equally reliable. If participants viewed the reliability of the two sources of information as the same, what caused them to conform more to their fellow participants’ choices? The answer lies in what occurred whenever they resisted the consensus of other people. The sector of their brains associated with negative emotion (the amygdala) became activated, reflecting what the researchers called “the pain of independence.” It seems that defying other people produced a painful emotional state that pressured participants to conform. Defying a set of computers didn’t have the same behavioral consequences, because it didn’t have the same social-acceptance consequences. When it comes to group dynamics, there’s an old saying that gets it right: “To get along, you have to go along.”

Take, for example, the account by Yale psychologist Irving Janis of what happened in a group of heavy smokers who came to a clinic for treatment. During the group’s second meeting, nearly everyone took the position that because tobacco is so addicting, no one could be expected to quit all at once. But one man disputed the group’s view, announcing that he had stopped smoking completely since joining the group the week before and that others could do the same. In response, his former comrades banded against him, delivering a series of angry attacks on his position. At the following meeting, the dissenter reported that after considering the others’ point of view, he had come to an important decision: “I have gone back to smoking two packs a day; and won’t make any effort to stop again until after the last meeting.” The other group members immediately welcomed him back into the fold, greeting his decision with applause.

These twin needs—to foster social acceptance and to escape social rejection—help explain why cults can be so effective in recruiting and retaining members. An initial showering of affection on prospective members, called love bombing, is typical of cult-induction practices. It accounts for some of the success of these groups in attracting new members, especially those feeling lonely or disconnected. Later, threatened withdrawal of that affection explains the willingness of some members to remain in the group: After having cut their bonds to outsiders, as the cults invariably urge, members have nowhere else to turn for social acceptance.10

Similarity: Peer-suasion

The principle of social proof operates most powerfully when we are observing the behavior of people just like us. It is the conduct of such people that gives us the greatest insight into what constitutes correct behavior for ourselves. As with “the many,” an action coming from similar others increases our confidence that it will prove valid, feasible, and socially acceptable should we perform it. Therefore, we are more inclined to follow the lead of our peers in a phenomenon we can call peer-suasion.

Studies have shown, for example, students worried about their academic performance or about their ability to fit in at school improved significantly when informed that many students like them had the same concerns and overcame them. Consumers became more likely to follow the consensus of other consumers about purchasing a brand of sunglasses when told the others were similar to them. In the classroom, when adolescent aggression is frequent, it spreads contagiously—but almost entirely within a peer group; for instance, frequent aggression of boys in a class has little effect on the aggressiveness of the girls and vice versa. Employees are more likely to engage in information sharing if they see it modeled by fellow coworkers than by managers. Physicians who overprescribe certain drugs, such as antibiotics or antipsychotics, are unlikely to change this behavior in a lasting fashion unless informed that their prescription rate exceeds the norm of their peers. After an extensive review of environmental behavior change, the economist Robert Frank stated, “By far the strongest predictor of whether we install solar panels, buy electric cars, eat more responsibly, and support climate-friendly policies is the percentage of peers who take those steps.”11

Figure 4.4: “Freethinking Youth”

We frequently think of teenagers as rebellious and independent-minded. It is important to recognize, however, that typically this is true only with respect to their parents. Among their peers, they conform massively to what social proof tells them is proper.

© Eric Knoll, Tauris Photos

This is why I believe we are seeing an increasing number of average-person testimonials on TV these days. Advertisers know that one successful way to sell a product to ordinary viewers (who compose the largest potential market) is to demonstrate that other “ordinary” people like and use it. Whether the product is a brand of soft drink or a pain reliever or an automobile, we hear volleys of praise from John or Mary Everyperson.

Compelling evidence for the importance of similarity in determining whether we will imitate another’s behavior can be found in a study of a fundraising effort conducted on a college campus. Donations to charity more than doubled when the requester claimed to be similar to the donation targets, saying “I’m a student here too,” and implying that, therefore, they should want to support the same cause. These results suggest an important consideration for anyone wishing to harness the principle of social proof. People will use the actions of others to decide how to behave, especially when they view those others as similar to themselves.

I took this consideration into account when, for three years, I served as chief scientist for a then startup firm, Opower, that partners with utility companies to send residents information about how much energy their household is using compared with their neighbors. A crucial feature of the information is that the comparison is not with any neighbors but is specifically with neighbors whose homes are nearby and comparable along dimensions such as size—in other words, “Homes just like yours.” The results, driven mainly by householders reducing their energy consumption if it is greater than their peers’, have been astounding. At last count, these peer comparisons have saved more than thirty-six billion pounds of CO2 emissions from entering the environment and more than twenty-three trillion watts per hour of electricity from being expended. What’s more, the comparisons are presently generating $700 million in bill savings to utility customers per year.

Peer-suasion applies not only to adults but also to children. Health researchers have found, for example, that a school-based antismoking program had lasting effects only when it used same-age peer leaders as teachers. Another study found that children who saw a film depicting a child’s positive visit to the dentist lowered their own dental anxieties principally when they were the same age as the child in the film. I wish I had known about this second study when, a few years before it was published, I was trying to reduce a different kind of anxiety in my son, Chris.

I live in Arizona, where backyard swimming pools abound. Regrettably, each year, several young children drown after falling into an unattended pool. I was determined, therefore, to teach Chris how to swim at an early age. The problem was not that he was afraid of the water; he loved it, but he would not get into the pool without wearing his inflatable inner tube, no matter how I tried to coax, talk, or shame him out of it. After getting nowhere for two months, I hired a graduate student of mine to help. Despite his background as a lifeguard and swimming instructor, he failed as I had. He couldn’t persuade Chris to attempt even a stroke outside his plastic ring.

About this time, Chris was attending a day camp that provided a number of activities to its group, including the use of a large pool, which he scrupulously avoided. One day, shortly after the graduate-student incident, I went to get Chris from camp and, with my mouth agape, watched him run down the diving board and jump into the deepest part of the pool. Panicked, I began pulling off my shoes to jump in to his rescue when I saw him bob to the surface and paddle safely to the side of the pool—where I dashed to meet him.

“Chris, you can swim!” I said excitedly. “You can swim!”

“Yes,” he responded casually, “I learned how today.”

“This is terrific! This is just terrific. But how come you didn’t need your plastic ring today?

“Well, I’m three years old, and Tommy is three years old. And Tommy can swim without a ring, so that means I can too.”

I could have kicked myself. Of course it would be to little Tommy, not to a six-foot-two graduate student, that Chris would look for the most relevant information about what he could or should do. Had I been more thoughtful about solving Chris’s swimming problem, I could have employed Tommy’s good example earlier and perhaps saved myself a couple of frustrating months. I could have simply noted at the day camp that Tommy was a swimmer and then arranged with his parents for the boys to spend a weekend afternoon swimming in our pool. My guess is that Chris’s plastic ring would have been abandoned by the day’s end.12

READER’S REPORT 4.5

From a university teacher in Arkansas