This chapter looks at procedures and problems that are particular to women’s organs and the female body. It covers some of the conditions that affect large numbers of women—conditions for which it is sometimes difficult to get reliable women-centered information. Much is still unknown about many of these conditions, though new research findings emerge regularly.

These conditions are organized by anatomy. Some problems, of course, will involve more than one area of the body. The chapter focuses on benign (noncancerous) diseases or problems and on cancer prevention and diagnosis. It deals less with cancer treatments, since they tend to change quickly.

Other chapters in this book cover many topics related to medical concerns. In particular, see Chapter 2, “Intro to Sexual Health” for information on preventive care for sexual and reproductive health and what to expect in a gynecological exam, and Chapter 23, “Navigating the Health Care System” for information on how to find good care, how to work collaboratively with a health care provider, and where to find trustworthy and up-to-date health information.

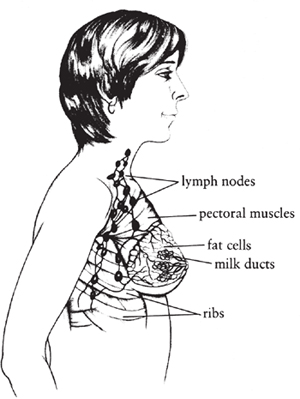

© Christine Bondante

A breast, showing the structure of milk ducts, lymph nodes, and fat cells.

Our breasts are dynamic organs. They change considerably during our lifetime in response to aging and to variations in our body’s hormone production. Understanding these changes can help reassure us when we think something is going wrong.

The breasts respond to estrogen and progesterone during each menstrual cycle, with growth and fluid retention that may be barely noticeable for some women but painful for others. The individual differences in breasts, along with the changes caused by age and menstrual cycles, can produce needless anxiety. We may worry that every change or pain is a symptom of cancer, when in fact most conditions causing change, lumps, or pain are benign.

Small cysts (a lobule or duct with fluid inside) may form, but they are usually smaller than a pea. Benign (noncancerous) tumors, such as fibroadenomas, may form during the teens and twenties and grow large enough to feel like smooth, mostly round, rubbery marbles that can be moved back and forth in place.

As we mature, small cysts may fill up further with fluid, sometimes causing tenderness and growing to sizes that can be felt with the fingers. By our fifties, dense glandular tissue and stroma begin to decrease (a process called involution), and fatty tissue increases. During perimenopause, hormone levels begin to fluctuate, and our usual cycles may become irregular. Effects of hormone changes on the breasts may include increased pain and lumpiness, which might be worrisome if we are looking for signs of breast cancer. Cancer rarely forms within cysts, but we may feel anxious while awaiting proof that a cyst is not cancer.

Some women’s breasts remain lumpy after menopause. Most benign lumps are caused by hormone stimulation, so if you are taking hormones after menopause, the breasts will continue to feel as they used to. Cysts rarely form after menopause, so if a new lump does form, it’s a good idea to have your health care provider examine it. Breast pain in the postmenopausal years may be coming from the chest wall, arthritis of the spine, or, only rarely, cancer.

There are several kinds of breast lumps. Cysts are fluid-filled sacs that develop from dilated lobules or ducts, most commonly during our forties or fifties. They can be identified by ultrasound or by removing the fluid and making sure no lump remains. Simple cysts—those that are just fluid, for example—don’t have to be removed unless they are causing pain or are so big that you can’t feel the surrounding breast tissue. A breast ultrasound is the best way to be sure a cyst is simple.

Treatment involves numbing the skin with a local anesthetic, inserting a thin needle into the cyst, and drawing the fluid into a syringe—a process called aspiration. The fluid may look gray and cloudy, dark and oily, or clear yellow or green. If a lump remains after aspiration, or if the fluid looks dark and bloody, you’ll need to have the area biopsied (tissue will be removed and examined under a microscope for further diagnosis). Cysts may refill with fluid after aspiration. If the same cyst continues to refill, removal may be recommended.

Fibroadenomas are benign growths that form mostly during our teens and twenties; some that form early may last throughout life. They may develop in one or both breasts. A fibroadenoma that’s getting larger is usually removed surgically. These growths sometimes shrink at menopause, as hormone levels decrease. Fibroadenomas are rarely associated with cancer, although some breast cancers can feel like fibroadenomas. The younger you are, the more likely it is that you have a fibroadenoma and not a cancer. Often a mammogram can confirm that the lump is a fibroadenoma, but the only way to be certain is by doing a biopsy and looking at the tissue under a microscope.

Pseudolumps are areas of dense normal breast tissue. They develop in many women during the premenopausal years. To make sure there is no cancer, these areas should be evaluated with good breast imaging and follow-up breast exams.

Cancer in the breast usually feels firm and hard. It often does not have clear edges but blends into the surrounding breast tissue. Breast cancers are usually about 1 centimeter (half an inch) in size before you can feel them; in women with firmer, lumpier breasts, they must be even larger to be felt.

First of all, don’t panic! More than 80 percent of all breast lumps are not cancer, especially in women under forty. Lumps in our breasts big enough to feel may be cysts, benign tumors such as fibroadenomas, pseudolumps, or cancers. It is impossible to tell the difference with physical examination alone. A lump that gets smaller over time is unlikely to be cancer. A lump that remains the same size or gets bigger could be cancer, so it should be medically evaluated.

Many women feel anxiety and fear upon finding a lump and immediately think it’s cancer. Our reactions may vary from wanting to go to the doctor immediately to being immobilized by fear. Finding a lump requires taking some decisive actions for yourself and your health. Tell someone you love about your concerns, so you can get some support and not have to go through the next steps alone. Then, contact your health care provider. Tell the appointment person or nurse that you have found a new breast lump and ask to be seen promptly.

Your clinician will do a physical examination of your breasts and determine whether further evaluation is necessary. She or he may suggest following the lump for one or two months, schedule you for diagnostic breast imaging (mammogram or ultrasound), and/or refer you to a breast specialist (usually a surgeon). If more information is needed, a biopsy may be recommended, since only a tissue sample determines for sure whether a lump is cancerous or benign.

This can be a very stressful time. Even though it’s likely that a breast lump is benign, statistics don’t always calm our fears. It helps to speak frankly with your health care provider about your concerns and to have the support of friends and/or family. It is also important to have confidence in your health care provider. If you are not comfortable with his or her recommendations, particularly a “wait and see” approach, be sure to say so. Getting a second opinion may be a good idea in this situation.

Breast discharge, itching on the areola, breast pain, and a breast infection are some of the other benign conditions of the breast that women experience. Nipple discharge, especially if it is bloody or coming from just one breast, should always be evaluated because it can be associated with cancer. Consult your health care provider for any persistent and troubling symptoms.

Mammography is the primary means of screening women at average risk for breast cancer. It utilizes a low dose of radiation to identify malignant tumors, especially those not easily felt by hand. A mammogram can also further investigate breast lumps that have already been identified, as well as other symptoms. Mammography involves X-ray radiation passing through the breast, producing an image on film or on a digital recording plate.

From 1975 to about 1990, the age-adjusted mortality rates from invasive breast cancer increased. In about 1990, they began to fall. By 2007, mortality had fallen by about one-third compared with its peak in 1989 and by 28 percent compared with 1975.1 It is not clear how much of the decline in mortality is due to screening mammography. (For a discussion of routine mammogram screening for all women over age forty).

Digital images can be enlarged and the contrast adjusted, enabling radiologists to concentrate on suspicious areas. This improves their ability to detect tumors in dense breast tissue. Digital images can also be stored and transmitted electronically, making it easier to consult with experts at a distance. For women under age fifty, women who are pre -or perimenopausal, and women who have dense breasts, digital mammography may work better, but for most women over age fifty, the use of digital mammography does not seem to catch cancers earlier or improve outcomes.

Ultrasound imaging—also called sonography—may be used to evaluate abnormalities that appear on regular mammograms. This technique excels in distinguishing solids from liquids, so it’s useful for differentiating solid tumors from fluid-filled cysts, which are benign. Ultrasound can also be used to guide needle biopsies. Ultrasound works by creating an image from reflected high-frequency sound waves emitted by a device called a transducer, a microphone that helps magnify the sound. Ultrasound is not useful as a screening tool by itself.

Recently, two medical devices have been developed to address the problem of missed tumors following mammography in women with dense breasts, a condition present in about one-third of women having mammograms today. One of these automated whole-breast ultrasound devices has been shown in a large, well-designed study to significantly improve cancer detection compared with mammography alone.2 This technique is not yet widely available.

MRI is quite effective in detecting invasive breast cancer, but it also can falsely identify benign lesions as malignant. It is not a substitute for regular mammography, nor is it for screening of the general population. Some recommend it for screening women at very high risk for breast cancer. MRI uses a powerful magnetic field and radio frequency pulses that are processed by a computer to create images of organs and tissues. It does not use ionizing radiation (X-rays) but does require an intravenous contrast injection.

PEM is used in addition to mammography to identify small invasive cancers and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—cancer that is confined to the milk ducts. PEM is not yet widely available and may not be covered by insurance. It uses gamma rays to detect “hot spots” of rapidly growing cells, and a computer analyzes the image to determine the size, shape, and location of the mass. The efficacy of PEM is still under study.

Like PEM, BSGI is used along with mammography. It is not widely available and needs more research to determine how well it works. It may not be covered by insurance. BSGI employs a radioactive tracer to identify cancer cells.

Thermography is used to assist in the diagnosis of breast cancer, but it produces too many false-positive and false-negative results to be used alone as a screening tool. It records the temperature of different areas of the body by measuring infrared radiation. Malignant tissue generally has a higher temperature than normal tissue because of its richer blood supply and higher metabolic rate.

In the future, as less invasive and more effective approaches are sought for early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, newer imaging technologies that look at breast cancer at the cellular level may become more widely used if there is clear evidence of their effectiveness as screening tools. Currently, BSGI and PEM involve fairly high doses of radiation and are therefore not appropriate for routine breast cancer screening.

All experts agree that mammograms can find breast cancers when they are small, are more curable, and need less treatment. But there is disagreement among experts over how many are found or missed, how many are successfully treated when found, how many don’t need treatment at all, when to begin a regular mammogram schedule, and when to end it.

For women between age forty and forty-nine, there is wide disagreement about screening mammograms.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a highly respected expert group, issued new guidelines in November 2009 recommending that women in this age group discuss with their clinicians when to start screening and whether to begin screening at age forty after considering the benefits and risks and discussing personal preferences.

In doing so, the USPSTF retracted its previous guideline for this age group, which recommended routine (that is, automatic) screening every one to two years starting at age forty.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) and the American College of Radiology (ACR), however, both continue to recommend routine screening every year starting at age forty for all women.

There is agreement that mammography reduces death from breast cancer, even in women between the ages of forty and forty-nine. The USPSTF agreed that screening in this age group was responsible for at least a 15 percent decrease in mortality. So why the different recommendations?

The USPSTF used a rigorous method of evaluating mammography studies. It relied almost exclusively on prospective randomized trials comparing death rates from breast cancer in those randomized for screening against those randomized for observation only. Since the benefits of screening mammography have been widely acknowledged, only one randomized trial started during the last twenty years (because randomizing would have to assign some women to “no mammography,” which most researchers would consider unethical). Critics of the USPSTF position assert that the weight of the USPSTF review is based on radiology studies that are out of date, but other experts dismiss this criticism.

In addition, different expert groups give different weight to the factors against and for routinely screening forty- to forty-nine-year-old women.

Factors against routine screening starting at age forty: Breast cancer is much less common in this group than in older women; the number of false-positive tests (in which the mammogram suggests a woman has cancer, but a biopsy shows no cancer) is higher for younger women; and starting mammograms at forty would mean having exams every two years for an average of thirty-four years. Over a lifetime, a woman’s chances of needing a biopsy to prove she didn’t have breast cancer might be as high as 50 percent.

Factors for routine screening in women starting at age forty: Cancers that are found in this age group tend to be more aggressive than those found in older women, and screening done every year, instead of every two years, may catch more of these aggressive cancers. While women may have to endure more biopsies, or anxiety with false-positive diagnoses, not getting screened can also produce anxiety.

It may be helpful to consider the comment of Dr. Ned Calogne, who chaired the USPSTF: “If I take 1,000 women age 40, over their lifetimes, 30 of them will die from breast cancer if we do no screening. If I screen every one of those women beginning at age 50 until she’s 74, we reduce the deaths from 30 to 23. And if I reach down and screen them in their forties, I can increase that by one additional life saved—at best.”3

Most experts agree that if a woman between the ages of forty and forty-nine is identified as being at high risk, she should be regularly screened (see “What Are the Risk Factors Associated with Getting Breast Cancer?”

All experts agree that women age fifty to seventy-four should be screened regularly.

Some experts say women in this group should be screened every year; others say every one or two years.

The USPSTF proposes screening every two years. It argues that the additional lives saved by screening yearly are not enough to justify an annual procedure. Screening at two-year intervals would preserve 81 percent of breast cancer mortality reduction seen with screening at one-year intervals.

The American Cancer Society and the American College of Radiology recommend screening every year. They argue that the 19 percent increase in breast cancer deaths that comes with screening only every two years is not acceptable.

For women over seventy-four, there is disagreement.

The USPSTF makes no recommendations, because there are no randomized studies for this age group. The ACS and the ACR recommend annual screening as long as a woman has a life expectancy of five to seven years (most experts believe that the benefits of mammography compared with no mammography show up only after five years). They also note that it is easier to find breast cancer in older breasts and breast cancer risk increases with age. They also believe that the risks of screening are small.

The decision to screen or not screen in this age group, all agree, should rest on a discussion with one’s clinician/primary care provider. Whether it’s better to be screened every year or every two years is disputed. The incidence of breast cancer continues to increase into one’s eighties, although most of these breast cancers are not as aggressive as those found in younger women.

Clearly, mammography can find curable breast cancers, even though there are disagreements about when to start routine screening. Weighing your personal preferences and concerns along with the recommendations of experts can be confusing and very stressful, especially if you have personal risk factors or friends or relatives who have faced breast cancer. Nevertheless, informed deliberation will help you make the best decision for you.

A woman living in the United States has a one in nine lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. While any woman can develop breast cancer, the chances increase with age. Breast cancer in men is extremely rare but does occur (about 1 in 100 individuals diagnosed with the disease will be male). Most breast cancer occurs in women with no family history or known genetic risk. In fact, 70 to 80 percent of women with breast cancer have none of the known risk factors besides age. Only 5 to 10 percent of cases are in women with high-risk mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. About 255,000 women per year are diagnosed with breast cancer, both noninvasive ductal carcinoma in situ (approximately 62,000) and invasive breast cancers (approximately 192,000). The National Cancer Institute estimates that there are more than 2.5 million women living with breast cancer in the United States.

Breast cancer incidence is highest in the United States and in western and northern Europe. The lowest rates are in Asia and Africa, although incidence rates have been rising in areas such as Japan, Singapore, and urban China. These regions are moving toward more Western economies and patterns of reproductive behavior. Although the influence of dietary patterns is complicated, higher caloric intake at younger ages can lead to earlier onset of menstruation, which is a risk for breast cancer.

PROBABILITY OF DEVELOPING INVASIVE BREAST CANCER AMONG WOMEN5* |

||||||||

CURRENT AGE IN YEARS** |

|

RISK PER 1,000 WOMEN *** |

||||||

|

|

in 10 years |

|

in 20 years |

|

in 30 years |

|

Lifetime |

30 |

|

4 |

|

17 |

|

41 |

|

123 |

40 |

|

14 |

|

37 |

|

68 |

|

120 |

50 |

|

24 |

|

56 |

|

86 |

|

109 |

60 |

|

34 |

|

67 |

|

86 |

|

91 |

70 |

|

37 |

|

58 |

|

— |

|

65 |

* Based on an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registry for 2005–2007. | ||||||||

** Women who are free from invasive breast cancer at their current age. | ||||||||

*** Number of women in 1,000 who would develop invasive breast cancer in the next period of time. |

||||||||

The established risk factors for breast cancer do not account for all of the breast cancer cases. Despite the billions of dollars spent on breast cancer research, we have much to learn about why some women develop breast cancer and others don’t.

Starting in the 1970s, the incidence of breast cancer rose at alarming rates. Much of this long-term increase is believed to be due to delayed childbearing and having few children. Obesity is also a factor. And as more women have screening mammograms, more cases are found; that accounts for some of the increase.

Between 2002 and 2003 there was a decrease in the incidence of breast cancer, particularly among women ages fifty to sixty-nine. This drop in the number of breast cancer cases coincides with the release of research findings from the Women’s Health Initiative study (nhlbi.nih.gov/whi), which prompted many women to discontinue their use of hormone therapy.

Many people believe that the industrial processes and environmental damage that began during or after World War II play a major role in rising rates of breast cancer in Western countries. Research into environmental connections to breast cancer is the focus of organizations and foundations such as Silent Spring Institute (silent spring.org). Such research is difficult and frustrating because it entails identifying geographic breast cancer patterns in a population that is very mobile and hard to track.

Reproductive hormones play a role in the development of breast cancer because they can affect cell growth as well as promote the growth of an existing cancer. As women age, the effect of estrogen on breast tissue decreases. As we go through perimenopause and become postmenopausal, breast tissue changes to fat.

On mammograms, young normal breast tissue appears thick and white, but as the breast ages and turns to fat, it shows up dark on breast imaging. In part, this accounts for why breast cancers, which appear white on a mammogram, are more easily detectible in women after fifty, who are usually approaching completion of perimenopause. As Dr. Susan Love has commented, “Looking for cancer on a young woman’s mammogram [is] like looking for a polar bear in the snow.”6 Having denser breasts—with more glandular tissue in relation to fatty tissue—is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer. More research is being done to try to figure out why dense breast tissue is a risk factor and what, if anything, can be done for women with dense breasts.

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was the first randomized controlled study looking at women and hormone therapy (HT, formerly called hormone replacement therapy or HRT). It began in 1991 with the first results released in 2002 (see nhlbi.nih.gov/whi for more information). The major objectives of the WHI were to study cancer, osteoporosis, and heart disease among older women. The trial was stopped early in 2002 when researchers found that women who had taken a particular estrogen and progestin had a greater incidence of several diseases compared with women receiving a placebo.

For healthy women who took estrogen plus progestin, the research demonstrated an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, blood clots, and breast cancer. This same group also had a decreased risk of colorectal cancer and fewer fractures. After 2002, hormone therapy use declined in the United States and around the world. Many believe that this decline explains in large part the decline in incidence of breast cancer shortly afterward.

In 2006, the National Cancer Institute reported on the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS), which included women who had undergone hysterectomy and were given estrogen without progestin. (Women with a uterus who take hormones usually include a form of progesterone along with the estrogen, to reduce the chances that estrogen “unopposed” will lead to endometrial cancer.) Results from this study comparing women receiving estrogen with women receiving a placebo found that there was no difference in the risk of heart attack, but there was an increased risk of stroke and blood clots among the estrogen group. The effect on the risk of developing breast cancer was uncertain. (Estrogen made no difference in risk for colorectal cancer, but there was a reduced risk of bone fractures in women who took it.) The Million Women Study conducted in the United Kingdom7 did show a clear increase in breast cancer among women on estrogen alone.

Follow-up studies have shown that the increased risk for breast cancer with hormone therapy—including both estrogen and progestin—diminishes within five years of discontinuing hormones. Recent studies report that the breast cancers developing in women taking both estrogen and progestin are more aggressive and more lethal than doctors previously thought.

What all of this means for women is that long-term use of hormones (greater than five years) increases breast cancer risk.8 Each woman needs to discuss hormone use with her health care provider to determine what makes the most sense for her own situation. Some women consider using bioidentical hormones as an alternative to conventional hormones. Bioidentical hormones are chemically identical to the hormones produced by your body; there are many FDA-approved hormones that fit the definition of bioidentical, and their long-term safety has yet to be established. (See Chapter 20, “Perimenopause and Menopause,” for more discussion.)

Breast cancer develops when changes occur in genes in breast cells. In that sense, all breast cancer has a genetic element. But genetic does not mean inherited. Only an estimated 5 to 10 percent of breast cancer cases result from an inherited genetic predisposition. In other words, more than 90 percent of all breast cancer cases result from factors that are not inherited and, in many cases, are unknown.

We all inherit half our genes from our mother and half from our father. There are some genes that dramatically increase the risk of breast cancer. Two of them are called BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations. Blood tests have been developed—and are now aggressively marketed commercially—that can identify these mutations. A positive test result (having one of these mutations) does not mean that an individual will definitely develop breast cancer. Nor does a negative test mean that a woman won’t develop breast cancer; it means only that her lifetime risk is the same as that of most other women in the industrialized world. But for those individuals who have an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, there is a significantly increased lifetime risk of developing breast, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers. BRCA1 carriers have an average cumulative breast cancer risk (up to age seventy) of 65 percent, compared with 45 percent for BRCA2 carriers.

It’s important to consider the family history of breast and ovarian cancer from both your mother’s and your father’s sides of the family. Genetic testing should be considered only in limited circumstances.10 It is usually recommended that individuals with breast and/or ovarian cancer undergo testing for BRCA mutations because if the results are negative, their children would not need to be tested. Individuals without breast and/or ovarian cancer who are most likely to benefit from genetic testing are those of us who believe—because of a family history of two or more first-degree relatives (such as a mother or sister) with breast and/or ovarian cancer—that we may be mutation carriers and, if so, who want to take some action to try to reduce our cancer risk.

All genetic testing should be accompanied by written, informed consent; complete information about benefits and risks; and professional counseling about options. This is best done through one of the many cancer risk assessment programs located throughout the country. A comprehensive list of programs can be found on the websites of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (nsgc.org) and American Board of Genetic Counseling (abgc.net).

If you have BRCA gene mutations, several possible strategies can reduce your risk of breast and ovarian cancer. These include taking drugs such as tamoxifen or raloxifene; prophylactic—that is, preventive—mastectomy; and having the fallopian tubes and ovaries removed. Because the science behind these strategies is changing so rapidly, and because these are major decisions with important risks to consider, it’s best to consult experts, pursue the latest information about these options, and consider their possible effects on your life.

When you find out you have cancer, it’s normal to feel shock, disbelief, fear, and anger. This psychological trauma comes exactly when you need to focus all your energy on learning about your treatment options. The most important thing to remember is that a diagnosis of breast cancer is usually not a medical emergency. This means that you have time to seek out opinions about the best way to proceed and to choose physicians with whom you feel comfortable. You have the right to have all of your questions answered and to understand your treatment options fully before deciding what to do.

Doing whatever your doctor suggests may be appealing at a time when you need to be taken care of, but it does not always result in the best care. Although most doctors have good intentions, they tend to offer only the treatment they know best. It’s wise to get a second opinion before committing yourself to a plan, even if you feel confident with your first doctor. This is especially true if your physician has not fully explained your surgical treatment options.

Lumpectomy and radiation therapy (also called breast-conserving therapy) when compared with mastectomy (removal of the entire breast) has the same survival rates; that is, the same percentage of women who don’t die of breast cancer. If your surgeon is not explaining this to you, then you should definitely seek a second opinion. While in some circumstances a mastectomy may be recommended and be better for keeping the cancer from spreading, you should fully understand why your doctor is recommending it. Some physicians may be slow to accept new therapies until there’s more experience with them; some may be unwilling or unable to discuss all available treatments. Some states, including Massachusetts, California, and Minnesota, have laws that require patients to be informed of all medical options.

Even though you may have a good relationship with your health care provider, if you live in a small town you should strongly consider going to the nearest large city with a research-oriented or university hospital. These institutions generally keep up with ongoing studies, use a team approach, and may be more flexible about treatment. A local women’s health center, the National Cancer Institute (cancer.gov), or the American College of Surgeons (facs.org) can help you find appropriate cancer centers and specialists. Cancer centers usually have special breast cancer centers. The advantage of getting a second opinion or of being treated at a breast cancer center is that a team of specialists—medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists—will be involved with your care from the beginning. Private oncologists may not practice in teams, making coordination of your care more difficult. Certain breast cancer centers offer more treatment choices, including clinical trials testing new therapies.

If you meet income guidelines and were diagnosed under a federally funded screening program for uninsured or underinsured women, Medicaid will cover treatment for breast cancer. Some communities have local support groups for women with cancer, where you may be able to get help with transportation to medical appointments and with child care, as well as encouragement from other women who have had or are having similar experiences.

Surgery is usually recommended within six to eight weeks of the biopsy, so it’s okay to take time to adjust, ask questions, and find out about your options. In some cases, chemotherapy is used over several weeks or months to reduce the size of the tumor prior to surgery (this is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

When you are trying to decide about treatment, the most pressing question is likely to be “How can I maximize my chances of disease-free survival?” But you will also want to understand the long-term effects of cancer therapy. To decide on the best treatment, you also need to know the size of the tumor, whether or not there is cancer in the lymph nodes, the hormone status of your tumor (called ER/PR), and what the HER-2/neu* status of your tumor is. These are specific for each woman’s cancer, and these tumor markers can help individualize and optimize your therapy. Most of this information is available after the biopsy, and it is used to recommend systemic therapies (endocrine/hormone therapy or chemotherapy) and/or radiation. Usually the medical oncologist is the one who discusses appropriate treatment options based on the biopsy or surgery results.

It is important to learn about all the available options. The entire field of breast cancer medicine is changing rapidly. Old, established theories and treatments are being questioned, while newer techniques have not been used long enough to be completely evaluated. The 2010 edition of Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book and her website (dslrf.org) contain up-to-date and credible information on breast cancer treatment as well as important current research. The National Breast Cancer Coalition website (breastcancer deadline2020.org) takes an activist approach. Getting balanced information on the pros and cons of various treatment options will help with knowing what questions to ask and how best to proceed with your care.

Cancers are classified in stages. These stages provide some information about prognosis for an individual, as well as a mechanism for comparison of treatments and outcomes in different populations. Staging for breast cancer is based on three elements: tumor size or extent (T); which lymph nodes, if any, contain cancerous cells (N); and metastases—cancer detected by X-rays or scans in other parts of the body (M).

When cancer is first diagnosed, the clinical stage is identified by physical exam and some testing for metastatic spread. After surgery, lab analysis of the breast tissue and lymph nodes removed will determine the pathologic stage. The stage is important because doctors usually base their recommendations for treatment on how well other women with cancer at the same stage and similar history have responded to various treatments. The TNM stage is then grouped into five categories or overall stages.

BREAST CANCER STAGES* |

|||

STAGE |

SIZE |

AXILLARY LYMPH NODES |

COMMENT |

0 |

DCIS |

Negative |

Noninvasive |

I |

Less than 2 cm |

Negative |

|

IIA |

2–5 cm Less than 5 cm |

Negative Positive |

|

IIB |

More than 5 cm |

Negative |

|

IIIA |

Less than 5 cm More than 5 cm |

Positive and matted Positive |

|

IIIB |

Any size and spread to chest wall, skin |

Negative or positive |

|

IIIC |

Any size |

Spread to other nodes |

|

IV |

Any size |

|

Spread beyond breast and nodes to other organs of the body |

* For more information on breast cancer stages, see cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/breast/page 7. |

|||

Breast cancers are classified by whether they are noninvasive (or in situ) or invasive breast cancer. In situ tumors are made up of cells that when seen under a microscope look like but do not behave like cancer. They remain encapsulated within their usual environment—inside the duct or the lobule. There are no blood vessels or lymphatic vessels there, so these cells have no access to other parts of the body. In contrast, invasive (also known as infiltrating) breast cancer goes through the walls of the ducts and lobules, invading the surrounding fatty/fibrous portion of the breast tissue where blood vessels and lymphatic vessels lie.

LCIS is not cancer now—it’s considered a risk factor for the development of breast cancer someday. Because LCIS is not preinvasive, there’s no need to remove it unless it is found on a core biopsy. Because a core biopsy is a limited sample, the recommendation in this case is to have more tissue removed and examined to be sure there is no neighboring in situ or invasive cancer.

In studies of women with LCIS, 20 to 40 percent developed cancer (mostly invasive ductal carcinomas) over twenty years or more. Such cancers may occur anywhere within either breast, not only in the area where the biopsy was done.

DCIS is a noninvasive cancer. Many scientists believe DCIS will become invasive cancer if enough time passes. But it may never become an invasive cancer in your lifetime. More women get this diagnosis now because improvements in technology have made it possible to find more and more DCIS with screening mammograms. Because DCIS can become an invasive cancer, treatment is usually recommended. There is unfortunately no way yet to tell which women really need treatment.

If you receive this diagnosis, get a second pathology opinion—preferably with a breast pathologist—before agreeing to any treatment. If possible get an opinion from a breast cancer center where you could meet with a multidisciplinary team of breast specialists.

Women diagnosed with DCIS have approximately a 1 percent risk of developing metastatic disease and 96 to 98 percent are alive ten years after diagnosis.12 Treatment aims to remove the area of DCIS and reduce the chance of a local recurrence within the breast. For years the customary treatment for DCIS was mastectomy. Early studies comparing a more breast-conserving approach with lumpectomy combined with radiation therapy showed similar rates for local recurrence of disease and no difference in survival. Now women have a choice regarding treatment options. For breast-conserving therapy, a procedure similar to lumpectomy, called wide excision or partial mastectomy, is performed with the goal of clearing the margins of DCIS (meaning no DCIS is found at the edges of the tissue removed). For some women, even after several excisions, DCIS remains at the margins and mastectomy is recommended.

There is a lack of consensus in the medical community regarding whether radiation therapy is needed for all women diagnosed with DCIS. Studies have not yet provided strong evidence suggesting that adding radiation therapy is more or less effective than wide excision alone.

In invasive or infiltrating breast cancer, the breast cancer cells have moved outside the ducts or lobules into the surrounding tissue. Because the tumor cells can spread to other parts of the body, through either the blood or the lymph system, treatment usually requires both local surgical and possibly radiation therapy, along with systemic treatments, such as hormone-locking medicines and/or chemotherapy.

An unusual but very aggressive form of breast cancer is known as inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). The first symptom is usually redness of the skin, along with an orange peel appearance of the skin called peau d’orange (which is why it is called inflammatory). Usually an antibiotic is prescribed to see if the redness is caused by an infection. If it doesn’t get better, a biopsy of the breast and the skin will diagnose the cancer. The usual treatment is chemotherapy first, followed by mastectomy and radiation.

As researchers discover more about the biology of breast cancer, treatment theories change. Breast cancer, in general, grows slowly. Most breast cancers have been growing for six to ten years before they are large enough to be seen on a mammogram or felt during an exam. During this time, cancer cells could be spreading (metastasizing), through blood vessels and the lymphatic system, to other places within the body. This doesn’t always happen—not all breast cancer cells survive outside the breast. Also, the size of the cancer doesn’t always correspond to how aggressive it is; the type of cells in it will affect what happens, too. However, there is no sure cure. A classic saying among breast cancer survivors is that you don’t know you’re cured until you die from something else. Women who have been successfully treated “so far” refer to being NED, or having No Evidence of Disease.

Current treatments for breast cancer are either local (therapy to the breast) or systemic (therapy to the whole body). Surgery and radiation are local therapies; chemotherapy, endocrine/hormone therapy, and biologic/targeted therapy are systemic therapies because they reach other parts of the body beyond the breast.

Almost all women with breast cancer get some kind of local therapy, typically a combination of surgery with or without radiation therapy. The two usual surgical treatment options are (1) lumpectomy (breast-conserving therapy) followed by localized radiation to the affected area or (2) mastectomy. Some sort of lymph node testing is done for invasive cancers or noninvasive cancers that are more than 5 centimeters in size. A sentinel node procedure can be done when there are no palpable nodes (nodes that can be felt) under the arm. This involves removing only the nodes closest to the cancer, called the sentinel nodes. If those nodes do not show a spread of the cancer from the breast, then the more extensive operation removing more axillary nodes, which used to be standard, is not needed.

Overall survival depends on whether cancer cells have already spread beyond the breast to other parts of the body, and if so, on the effectiveness of systemic therapy. Local therapy may make a difference in the risk of local recurrence within the breast or how likely the cancer is to come back within the breast/chest area. In general, deciding whether it’s a good idea to have systemic therapy (such as hormone/endocrine therapy) depends on what testing suggests about whether the cancer might spread and on how you feel about the risks and side effects.

Questions to ask your health care team so that you can be as well informed as possible include the following.

At initial diagnosis:

• Please explain to me the type of breast cancer that I have. Is it noninvasive DCIS or invasive cancer?

• How can I get an appointment with a breast surgeon? Are there hospitals near where I live that have multidisciplinary breast cancer programs with a team of breast specialists I can meet in one visit?

• What information do I need to bring with me to my visit?

• Do you have a breast pathologist who can review my slides? How would we get a second opinion on the pathology?

• Can we review my pathology report? What is meant by “grade”?

• What is staging and what is my stage of disease?

• Do I need any additional testing and if so, why?

• What support services are available for me and whom can I talk with?

• Is there someone who can follow me through treatment and be available to answer questions?

When discussing local surgical treatment options:

• Can I have a breast-sparing lumpectomy and radiation therapy?

• If not, why not?

• Can you walk me through the surgical procedure?

• Will there be a lymph node procedure, and if so, what kind?

• Explain your technique for a sentinel node biopsy (used to determine if cancer has spread into the lymphatic system). What does it mean when a sentinel “lights up”? How many of these procedures have you done? How many false-negative cases are there?

• What is the risk of a local recurrence in my breast or chest wall if I have a mastectomy?

• What is my risk of developing breast cancer in my other breast?

• If mastectomy is recommended or if I choose to have a mastectomy, can breast reconstruction be done? What types of reconstruction would be available?

• If I have a lumpectomy (also called partial mastectomy and wide excision), what are the chances you will not get clear margins?

• How many breast surgeries do you do in one month?

• How will the pathology results of my surgery influence my overall treatment?

• Walk me through the recovery process. What will I be able to do and not be able to do?

• What restrictions will there be on my activity? Can I exercise?

• How long do I need to miss work?

• If I have a mastectomy, how long will I be in the hospital? Will I need help at home afterward?

• What are possible short-term and long-term complications of the surgery?

Questions for the radiation oncologist:

• What happens during the radiation treatments?

• What will the side effects be?

• Will I be tired from my treatments? Can I work during my radiation therapy?

• How many treatments will I need?

• I hear there is a shorter course of radiation therapy that takes less than six weeks. Can I have the shorter treatment? If not, why not?

Questions for the medical oncologist:

• Please explain to me what ER and PR and HER-2/neu mean.

• How are these markers used in planning my treatment?

• When would chemotherapy begin?

• What are the immediate (short-term) and long-term side effects of the drugs I’m supposed to take?

• What happens to my veins? What is a port, and will I need a port during treatment?

• Is there a clinical trial appropriate for me?

• If I need chemotherapy, can someone give me a tour of the treatment area?

• Are there integrative therapies such as Reiki, acupuncture, and massage that I might use to help manage the side effects?

Lifestyle questions:

• What exercise can I do during my treatment?

• Can I dye my hair during treatment? Will I lose my hair during treatment?

• Can I travel during treatment?

• Will I gain weight or lose weight during treatment?

• Are there special foods that I should eat or avoid during my treatment?

Some women who have had a mastectomy feel comfortable doing nothing to “fill in” the place where a breast is missing, choosing not to get an external prosthesis or have breast reconstruction surgery:

I refuse to have my scars hidden or trivialized behind lambswool or silicone gel. . . . I refuse to hide my body simply because it might make a woman-phobic world more comfortable. . . . I am personally affronted by the message that I am only acceptable if I look “right” or “normal.”

Others of us don’t want a visible scar, and some worry that other people may be repelled by it. Some decide to use a prosthesis inside a bra, to fill in the area and “match” the other side under clothing. Some prefer to have breast reconstruction done by a plastic surgeon; this is done by using your own tissue and/or an implant.

With an external prosthesis, you may look as if nothing has changed, as long as you wear your bra, which holds the prosthesis in place. It may shift under your clothes or feel heavy; it may be hot in the summer and cold in the winter. However, the feel, fit, and comfort of prostheses are continually improving. Stores and online companies that specialize in prosthesis fitting can custom-make one to fit your anatomy. You can get a temporary prosthesis after surgery; once your scar has healed, you can be fitted for a permanent one. Many health plans cover all or part of the cost of a prosthesis. Medicare will pay for one every year or two if you get a prescription from your doctor. If you have health care insurance, ask your insurance company what costs it will cover.

Breast reconstruction is a surgical option either at the time of the mastectomy or later. Some physicians pressure women to start reconstruction at the same time that they undergo a mastectomy. Although this may provide a psychological boost and slightly reduce the number of surgeries, it’s also okay to wait and see how you feel. If it seems that you have too many decisions to make all at once—sorting out your cancer therapy as well as whether to have reconstruction and what kind—then don’t rush into it. You will also want to learn about important safety considerations, especially regarding silicone breast implants.

Surgical reconstruction involves using either an implant under the chest muscle or your own tissues, with blood vessels, moved from your back, abdomen, or buttocks to your chest area (called a flap reconstruction). Sometimes an implant is used to supplement the tissue transfer operation. Reconstruction is not without risks, both during surgery (risk of blood loss or infection) and later on, but it also may have physical and emotional benefits.

An implant is a flexible synthetic envelope made of silicone and filled with salt water (saline) or silicone gel. The implant is placed behind the pectoral muscle or a flap of your own tissue and then the skin is sewn together. If there’s not enough space for the implant, a flexible expander is put in first to stretch the overlying tissues with saline injections over three to six months. Once the space is the right size, the expander is removed and replaced with a permanent implant.

Many women have developed debilitating conditions after breast implant surgery. The two major breast implant manufacturers have both reported a very high rate of complications after reconstruction with their implants. Here are the statistics from one company, for women two or three years after surgery: 46 percent needed additional surgery; 25 percent had their implants removed; 6 percent had substantial breast pain; 6 percent had necrosis (death of tissue); and 6 percent had ruptured implants, often with “silent” and prolonged leakage of silicone into their bodies.13 These complications were expected to increase over the following years.

Both manufacturers also reported a significant increase of symptoms associated with autoimmune diseases, including joint pain, fatigue, hair loss, and muscle pain. This increase happened within two years of getting implants.14 Unfortunately, the companies never published those findings in medical journals.

We need more research on women who have had breast implants for at least ten to twelve years, since most leakage or rupture occurs after that period of time. Some research has found an increase in fibromyalgia and some autoimmune diseases among women with leaking silicone gel breast implants. We need better research to determine how often women with leaking silicone implants suffer from autoimmune symptoms, not just autoimmune diseases.

Make sure you consult a board-certified plastic surgeon to find out what type of reconstruction is best for you. If the reconstruction uses muscle from somewhere else on your body (such as a TRAM flap), you will lose strength at the spot it came from. This is less likely if you have a tissue transfer that does not use muscle, such as the DIEP flap, which instead uses fat and skin tissue from the abdomen. If you want to consider a TRAM flap or DIEP flap, it’s especially important to find a plastic surgeon who is very experienced at that type of procedure, because experience increases the chances of success in these more complicated surgeries.

For any reconstruction, ask how long the recovery period is for the operation being recommended. If you smoke or have diabetes, complications may be more likely, as your blood vessels may be narrower or damaged, and healing can be more difficult. If you are active, especially in a particular sport, ask your surgeon to try to make it possible for you to return to this activity eventually. Once you get a recommendation, ask to speak with other women who have had the same procedure, both with this surgeon and with others. You can find other women to talk to through oncology social workers as well as through breast cancer support groups and other organizations. Breast Cancer Action (bcaction.org) is a great place to start.

If you have one breast removed, the plastic surgeon will probably try to make your two breasts look as similar as possible. This is difficult with implants, which tend to make the new breast much higher and rounder than the remaining breast. Some plastic surgeons recommend a breast lift and/or an implant in the remaining breast, so that the two breasts will be more symmetrical.

Consider the possible problems that can result from additional surgery and its risks. Further recovery time and side effects, such as loss of nipple sensation, should be taken into account. It is also important to know that an implant in the remaining (healthy) breast is likely to interfere with the accuracy of mammography, since the implant shows up as a solid white shape on the mammogram, hiding any cancer above or below it. To try to improve the accuracy, whenever you go for a mammogram, the technician should take additional mammography views (called displacement views). These views are important to detect cancer, but they expose you to more radiation and could thus increase your risk of breast cancer in the future. In addition, the pressure from a mammogram can cause an implant to break or leak. For those reasons, women who undergo reconstruction should seriously consider whether they want the additional risk of an implant in the remaining breast.

If you are considering reconstruction, make sure the surgeon understands what you want; she or he may have something different in mind. It’s important to mention what size you would like to be and make sure the surgeon agrees. If you are planning a TRAM flap or DIEP flap, talk to your surgeon about how you feel about having a second scar where your own tissue will be taken for the operation. Your body size and how much flesh you can spare may be a factor in whether these procedures work for you. Some plastic surgeons suggest a tissue flap with an implant, but that means you have the longer recovery time of the flap surgery and all the long-term complications of the breast implant. Ask about newer procedures that may be less damaging. Take time to become as well informed about reconstruction as you are about treatment.

Whatever type of reconstruction you choose, the surgeon can create a nipple and areola using darker, grafted skin or a tattoo. This is usually done several months after the reconstruction surgery.

More than 200,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed every year in the United States; more than 44,000 women in the United States die of breast cancer each year. Currently, about three-quarters of women who get breast cancer are still alive ten years later, and almost two-thirds are still alive fifteen years later. Many women live long, healthy lives after a breast cancer diagnosis. But even with all the indicators available, it is difficult to make predictions for any specific woman. An individual’s immune system and general health are part of the picture, but there are still many unknown factors.

Current research is focusing on identifying biomarkers—proteins in the blood that indicate the presence of cancers and how they will behave. Research is also looking at ways to keep cancer cells from reproducing, such as cutting off the blood supply to tumors and changing the genetic instructions that make them grow out of control; and developing drugs that can target cancer cells without killing healthy ones. In the foreseeable future, further work in these areas should result in more individualized and effective treatments—and perhaps even a cure. Participating in research such as comparative studies or clinical trials of new treatments is an opportunity to contribute to progress in breast cancer research and can be meaningful for some women.

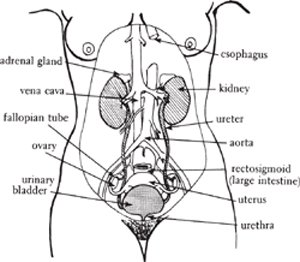

The uterus (womb) is a pear-sized organ made up of muscle that sits in the lower abdomen. It is lined with endometrium, hormonally sensitive tissue designed to nourish a developing embryo. Each month that a woman doesn’t conceive, this lining is shed through a menstrual period. The uterus can stretch to accommodate a growing fetus, then push the baby out and return almost to its former state. The cervix is the opening to the uterus. It protects the inside of the uterus from the outside world and then opens during labor to let a baby out.

This section covers some of the major conditions and problems we may experience with these parts of our body. For more information on the anatomy and function of the uterus and cervix, see Chapter 1, “Our Female Bodies.”

Fibroids are solid benign smooth-muscle tumors* that appear, often in groups, on the outside, inside, or within the wall of the uterus, possibly changing the size and shape of it. Many fibroids cause no problems at all, and many woman do not even know that they are present. Most women with fibroids can conceive and carry a pregnancy to term without any special treatment.

© Casserine Toussaint

A uterus without fibroids, left, and a uterus with fibroids (benign growths), right

Some fibroids, depending on size and location, can cause heavy vaginal bleeding, abdominal or back pain, urinary problems, and constipation. Sometimes they may make a woman’s belly look bigger. Fibroids that bulge into the uterine cavity (submucous fibroids) may make it difficult to conceive or to sustain a full-term pregnancy. There are several way to remove fibroids—which one is best depends on the size and location of the fibroids, as well as the skills of your surgeon. In at least 10 to 50 percent of cases in which fibroids are removed, new fibroids grow. However, only about 20 percent of women will require more treatment.

About 30 percent of all women get fibroids by age thirty-five and almost 80 percent of women will have fibroids by age fifty. Black women are more likely to have them, and to get them at a younger age. The cause of fibroids is unknown. About 40 percent of fibroids will grow during pregnancy, usually within the first three months. Some researchers used to think that using oral contraceptives made fibroids grow, but this is not as clear with low-dose pills. Very rarely, taking estrogen after menopause might affect fibroids.

Fibroids may be discovered during a routine pelvic exam. Because fibroids can grow, they should be monitored. If they haven’t grown any more by the time you have your next monitoring exam several months later, a yearly checkup will be enough. Ultrasound can give more definite information about the number and size of fibroids, but this is not always necessary.

If you have fibroids and abnormal bleeding, be sure to get carefully checked for other possible causes of the bleeding (see “Abnormal Uterine Bleeding”).

In many cases, no treatment is necessary for fibroids; this is called watchful waiting. If you are nearing menopause, the natural decline in estrogen levels at that time usually shrinks fibroids. Although many physicians recommend hysterectomy—removal of the uterus— as a treatment for fibroids, this is usually not necessary.

Myomectomy. If you have excessive bleeding, pain, urinary difficulties, or problems with pregnancy, you may want to have an operation called a myomectomy to remove the fibroids. Done by a skilled practitioner, myomectomy avoids some of the problems associated with hysterectomy and poses no greater risks. Even large, multiple fibroids can be removed with a myomectomy. There are several approaches, depending on the size and location of the fibroids.

Embolization of the uterine arteries. This procedure, performed by an interventional radiologist, cuts off blood supply to the fibroids, making them shrink. It reduces bleeding and tumor or uterus size in most women who have it done. The recovery time is typically shorter than for surgical removal of fibroids, if the procedure goes smoothly. Complications may include severe pain and fever that might require an emergency hysterectomy, damage to the uterus or other organs, and loss of ovarian function due to a constricted blood supply (this leads to premature menopause). For these reasons, this may be a risky approach for a woman who still wants to get pregnant.

Focused ultrasound surgery. Also called focused ultrasound ablation, this is another less-invasive option, but it can be used only for smaller fibroids and is not widely available.

Other treatments. Sometimes the drug leuprolide acetate (Lupron) is recommended to help shrink fibroids in women approaching menopause or planning to have surgery. However, Lupron has many negative effects, some of which may last many months beyond use of the drug. These include hot flashes, vaginal dryness, trouble with memory and concentration, and bone thinning. Also, after the Lupron is stopped, the fibroids can grow back.

The newest treatment, a medicated intrauterine device (IUD) called Mirena put into the uterus, can reduce bleeding and possibly enable you to avoid surgery.

Some women try to prevent or reduce fibroids by avoiding processed foods and the hormones usually found in commercial meat, dairy, and egg products, but there is no evidence that this will work. If your fibroids cause heavy bleeding, see the self-help treatments. Yoga exercises may ease the feelings of heaviness and pressure; some women find visualization techniques helpful, too.

Polyps are a focal buildup of the uterine lining. Sometime benign polyps can grow in the uterine lining and cause a woman to have heavy periods or bleeding between periods. Once they are diagnosed—usually by ultrasound, and sometimes by a procedure with a thin fiberoptic instrument called a hysteroscope—they are typically easy to remove. Removal is usually recommended because of the small risk (fewer than 3 out of 100 polyps) that they may be precancerous, and to treat abnormal bleeding.

The endometrium can also become hyperplastic owing to abnormal growth of the endometrial cells. This condition can cause abnormal uterine bleeding, especially in women who are not ovulating regularly or who are taking estrogen without progesterone (or a progesterone-like substance like a progestin). While endometrial hyperplasia is benign, another condition called atypical endometrial hyperplasia can be a precursor of cancer of the lining of the uterus (endometrial cancer). In this circumstance, a hysterectomy is sometimes recommended to prevent the development of uterine cancer. Benign endometrial hyperplasia may be treated with high-dose progesterone, depending on the woman’s age or intention to become pregnant, or with the Mirena IUD, which contains a progestin.

Endometrial cancer is the most common pelvic cancer, affecting fourteen out of every ten thousand women yearly. Most women with this cancer are over fifty and past menopause; 10 percent are still menstruating. If you are heavy for your size, take synthetic estrogen without a progestogen, or have diabetes, high blood pressure, or a hormone imbalance that combines high estrogen levels with infrequent ovulation, your risk of uterine cancer is increased.

During the early 1970s, there was a sharp rise in the incidence of uterine cancer because of estrogens prescribed for menopausal women without any additional progestogen (progestin or progesterone) to reduce the chances of endometrial hyperplasia. Taking progestogens usually prevents the development of this condition in women taking estrogen.

Bleeding (including light staining) after menopause is the most common symptom of uterine cancer. However, most women who bleed do not have cancer. For women who are still menstruating, increased menstrual flow and bleeding between periods may be the only symptoms. Unfortunately, the Pap test, while effective at detecting cervical cancer, is not reliable for detecting uterine cancer. If you have the above symptoms, your medical practitioner will probably recommend an aspiration or endometrial biopsy to sample the uterine lining—this is a simple office procedure. In some cases, a dilation and curettage (D&C) is preferred (performed with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia). Make sure that you have discussed the risks and benefits of these alternatives before making a decision.

Because endometrial cancer appears to be influenced by factors such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, controlling these conditions with self-help methods may prevent this type of cancer from developing. Exercise and a healthy diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables is the best strategy.

When uterine cancer is found early, the success rate of conventional treatments is very high. Medical treatment for uterine cancer includes surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. There is wide disagreement about which is best. Outside the United States, radiation is used frequently with good results. Hysterectomy is the most common treatment in the United States. Follow-up radiation after surgery is possible if the tumor was large, if it is found or suspected to have spread to the lymph nodes, or if cellular changes suggest a fast-growing tumor. Hysterectomy can often be done laparoscopically. If the cancer comes back after one of these treatments, progestogen treatment may help slow it down.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (which may include clots of blood) or bleeding happening outside the normal cyclic menstruation is referred to as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). AUB is a common gynecological problem, but its causes can be tricky to diagnose. The most likely cause of AUB for any woman depends on whether she is premenopausal, perimenopausal (near menopause), or postmenopausal.

Some causes of AUB include hormonal imbalances, pregnancy, the use of hormonal contraceptives (birth control pills or Depo-Provera, for instance), fibroids, endometrial polyps, infection, and, more rarely, precancerous or cancerous growths. Infrequently, bleeding that seems to be coming from the vagina may actually come from the urinary tract or gastrointestinal tract. For severe bleeding without an obvious explanation, ask to be screened for von Willebrand disease, especially if you have a history of other bleeding problems.

Fibroids can cause heavy, longer periods, sometimes with cramping and clots. More commonly, this occurs when the fibroids are submucosal and impinge on the uterine lining. Such periods are usually not irregular.

In addition to being a sign of a possible physical problem, heavy and/or irregular bleeding is a nuisance. It can also result in anemia from low iron and thus cause fatigue. Sometimes, heavy and prolonged bleeding may be part of the normal transition to menopause.

During perimenopause (the transition to menopause), new and different bleeding patterns are common. That makes it hard to decide when the menstrual cycle is normal and when there is a problem. The amount of blood flow may vary from month to month. Women sometimes skip their period for a few months, and then have regular periods again. However, if you are experiencing many episodes of irregular bleeding as described in the box above, it could be a sign of a medical problem that should be addressed.

Women who take hormone therapy may experience normal or abnormal uterine bleeding. You should understand what pattern is expected with your hormone prescription and contact your health care provider if your bleeding is different from what you’ve been told to expect.

Vaginal bleeding is abnormal in any woman who is postmenopausal (has gone a full year without any menstrual periods), unless she is taking hormones.

Clinicians will review a woman’s medical history. For premenopausal women who are missing periods, the bleeding pattern may suggest pregnancy or ovulation (producing an egg). A pregnancy test can find out whether an abnormal pregnancy is causing AUB. Blood tests can check for anemia, thyroid function, and female hormone levels. Other symptoms, such as pelvic pain or hair growth, can suggest other particular causes of AUB.

A clinician may be able to detect uterine abnormalities such as fibroids through a pelvic exam. Women with AUB should get a Pap test if one has not been performed recently.

Adenomyosis (endometriosis in the wall of the uterus, a condition affecting about 10 percent of women) is another cause of heavy and painful periods. It can be diagnosed only with an expensive MRI or a surgical specimen during a hysterectomy.

Four special tests are often used to evaluate AUB, as follows.

Endometrial biopsy: This is a quick office procedure involving the removal of tissue from the uterine lining (endometrium) to check for precancerous and cancerous cells. A thin tube, which is a suction device, is inserted into the uterus through the vagina and the cervical opening. It withdraws samples of uterine tissue for analysis. This may cause cramping, and some women will need pain medication, including anesthesia.

Transvaginal ultrasound: In this test, a wand placed in the vagina produces sound waves that create an image of the pelvic organs. The test can identify uterine fibroids. It measures the endometrial lining and may indicate abnormalities in the endometrium.

Sonohysterogram, or saline infusion sonography: This special kind of transvaginal ultrasound involves putting saline (salt water) into the uterus through a thin tube, to improve the image and detection of abnormalities.

Hysteroscopy: Diagnostic hysteroscopy involves threading a thin flexible scope into the uterus to view the contents of the uterine cavity. It can be done in the office or at a surgical procedure unit. Operative hysteroscopy is done at the hospital with anesthesia. A slightly larger scope is used to look at the uterine cavity and remove abnormal tissue such as fibroids or polyps.

The treatment for abnormal bleeding depends on what is thought to be its cause. A woman’s age and plans for childbearing, as well as her preference, are important in planning the treatment. Treatments range from observation (and taking iron, if a woman is anemic) to hysterectomy, or removing the uterus.

Various medications can reduce or regulate abnormal bleeding and relieve pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen) taken for pain may also reduce bleeding. Tranexamic acid is a medication that significantly decreases menstrual bleeding. Only recently introduced in the United States, it has been available in other countries for many years. Birth control pills make the cycle more regular and reduce bleeding, but there is some controversy about using them during perimenopause (See the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research for more information: cemcor.org).

An IUD (intrauterine device) treated with a progestin, such as the levonorgestrel-releasing Mirena, can be a nonestrogen hormonal option for controlling bleeding. Some other drugs, such as danazol and Lupron, reduce bleeding even more but also have serious negative side effects (see above); they are typically used for only a short time, to postpone or prepare you for surgery.

Noninvasive outpatient surgery (endometrial ablation) may be done with several techniques that cauterize, freeze, or remove the lining of the uterus to reduce bleeding. These include operative hysteroscopy (where the uterine lining is surgically removed) or the use of specially designed instruments such as the thermal balloon (ThermaChoice) or NovaSure to cauterize or even freeze the uterine lining. Endometrial ablation is an option after more serious causes of abnormal bleeding are ruled out. It may be less effective in the presence of fibroids. Hysterectomy is the only known effective treatment for adenomyosis.

Always discuss the particulars of your situation and your choices with your clinician. If you are uncomfortable with the options offered, try to get a second opinion.

If you are premenopausal, you may be able to stabilize your menstrual flow by reducing stress and changing your diet. Cutting down on animal fat and adding fiber helps to restore normal hormonal balance by lowering cholesterol, which is converted to estrogen in your body.

There is controversy about whether soy products—and which types—are beneficial for AUB or may help to regulate periods. Supplements of vitamins A, E, and C with bioflavonoids may help if your diet does not include enough of these vitamins. (Take no more than 10,000 IU of a vitamin A supplement twice a day, since larger doses can be toxic. One carrot contains 8,000 IU, and dark green leafy vegetables contain a lot, too, so you can get enough vitamin A from food.) If you are bleeding heavily, increase your iron intake to prevent anemia.

Some women find that Chinese medicine, including acupuncture and Chinese herbs, helps to restore hormonal balance. If you are approaching menopause, the bleeding may stop by itself as your hormone levels get lower.

The underlying cause of very heavy periods may be von Willebrand disease (VWD), the world’s most common inherited bleeding disorder. It’s a deficiency in the amount or quality of a protein that is required for blood to clot. VWD affects about 1 percent of people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds. Both men and women can inherit it from either parent. Because of our monthly periods, VWD affects females more frequently than males, but health care providers don’t always realize that is what’s wrong. The bleeding can range from being simply annoying to interfering with school, work, sleep, and mood.

VWD bleeding can be described as “oozing and bruising.” Bleeding typically occurs in the mucous membranes (for example, in the mouth after dental work, or in the rest of the gastrointestinal system). The most common symptoms are heavy or prolonged periods, easy bruising, prolonged nosebleeds, and prolonged bleeding following surgery, injury, dentistry, and childbirth. Other signs can be bleeding into the joints and urine. VWD may result in miscarriage and unnecessary surgery, including D&C, uterine ablations, and hysterectomy at a young age. Affected family members can have different bleeding patterns, as can people with the same type of VWD. Absence of bleeding does not rule out the disease. People with severe VWD have the same level of joint damage as do those with moderate hemophilia.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening all women with severe uterine bleeding for VWD. A federally supported U.S. hemophilia treatment center, if near you, may be a good place to seek help.

There is no cure for VWD, but there are effective treatments. Treatment varies according to how severe your condition is, and may include hormones, a synthetic nasal spray, or medication that is injected under the skin or infused into a vein. You may need to see a hematologist (blood specialist) familiar with VWD for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Cervicitis is a general term for inflammation of the cervix. A Pap test report or cervical biopsy may mention it, but it’s not always a real disease or disorder. Cervicitis may accompany vaginal infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and sexually transmitted infections.

Cervical eversion (also called ectropion) occurs when the kind of tissue that lines the cervical canal grows on the outer vaginal part of the cervix, making it red, with a bumpy-looking texture that is smooth to the touch. If the inside (columnar epithelium) puckers out, that is referred to as eversion. This is a common physical variation. Most women do not have any symptoms, although eversion can cause bleeding during a Pap test. Eversion requires no treatment unless it is accompanied by infection. Those of us whose mothers took diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy are more likely to have this condition.

Cervical erosion is a pinkish-red sore on the cervix, next to the cervical opening. This rare condition causes little discomfort. Most cases referred to as erosion in the past were really eversion.

Cervical polyps consist of excess cervical cells that “pile up” within the cervical canal. They appear as bright red tubelike protrusions from the cervical opening, either alone or in clusters. Polyps are very common and usually benign. Most polyps contain many blood vessels with a fragile outer wall, so bleeding may occur after intercourse or other vaginal penetration, douching, or self-exam. Polyps may also bleed during pregnancy, when hormonal changes stimulate growth of blood vessels in all cervical, vaginal, and uterine tissue.

Cells from the polyps will be collected as part of a Pap test. Cervical polyps are almost never cancerous.

Polyps do not necessarily require treatment. When they are small and there is little or no contact bleeding, you or your clinician can usually just keep track of them with regular exams. Removing cervical polyps is often recommended as a preventive measure but is not required. You may want to have them removed if the polyps begin to grow. This is a simple office procedure where your practitioner twists the polyp off and scrapes or cauterizes the base. If your polyp is very large (this is rare), or if you have several of them, you may have to go to the hospital for removal. Sometimes polyps grow back after removal.

Cancer of the cervix is responsible for the deaths of half a million women around the world every year. In some countries, it is the leading cause of cancer death in women. Cervical cancer deaths are on the decline in the United States, probably as a result of Pap tests (which can catch cervical cancer early) and the treatment of precancerous cervical problems called dysplasia. Most cervical cancer results from human papillomavirus (HPV) infections that are transmitted through sexual contact (In Chapter 11, “Sexually Transmitted Infections). The Pap test, often done as part of a routine gynecologic exam (see “Pap Tests”), is a screening test for precancerous or cancerous changes in cervical cells. Most of the cellular abnormalities we call dysplasia are now thought to be caused by HPV, but only some types of HPV are associated with cervical cancer. Tests that can identify the presence of these “high-risk” HPV types are now available.