(Abi Stafford in George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker)

I really enjoy cross-training. It makes me feel more energetic and helps so much with my overall strength.

—ABI STAFFORD, NYCB principal

Cross-training is the new buzzword for today’s serious dancer. Besides helping you nail more athletic choreography, it also reduces fatigue and injuries while improving the muscular shape of your body—that is, if you know what to do! Picking specific workouts and adding them to your dance schedule can be confusing, especially when the wrong match leaves you with bulkier muscles or a bad case of burnout. This chapter describes how to create an overall fitness program that works for you.

Why isn’t dance class enough? While regular class is essential to excel in a specific dance technique, it bypasses certain muscle groups, and it does not raise your heart rate sufficiently. In fact, 85 percent of technique class is not up to the stamina required to perform on-stage. The constant repetition of dance steps also stresses vulnerable areas of the body associated with teenage growth spurts, prior injuries, and your physique (for example, being tight- or loose-jointed). Thus, the value of an individualized cross-training program is twofold:

1. It improves your general level of fitness according to essential physical parameters (strength, flexibility, and aerobic capacity).

2. It compensates for specific areas of vulnerability after the age of twelve when dance training becomes more intense.

Still, cross-training is only effective if the workouts complement your dance schedule. While nonathletes can cross-train year-round to spice up their fitness program and prevent pain by alternating routines, dancers who add it onto a new training program or during a busy work period are significantly more prone to overuse injuries. This happened to sixteen-year-old Jason, whose intensive summer dance program introduced an hour of cross-training on top of a full day of classes and rehearsals. By the end of the month, he had developed a bad case of tendonitis, much to his dismay, and missed the final dance recital. The key to cross-training is to know what to do, when to do it, and how to find qualified instructors. The best time is to use it to get in shape or recover from an injury.

Cross-Training: Maximizing Your Dance Potential

The idea behind cross-training is that you use different routines to create a total body workout that increases endurance, strength, and flexibility, rather than focusing on only one of these components. In addition, because the body requires twelve to twenty-four hours to benefit from a workout, there are two ways to proceed. You can do two or more workouts on the same day (for example, aerobics, weight lifting, and stretching), followed by a free day. Or you can alternate a harder day (such as thirty minutes of interval training on the elliptical machine) with an easier day (like a Pilates session). According to Marika Molnar, professional dancers who need to prepare for late-night performances may choose to work out in the morning and the evening to get into shape.

Expert supervision with certain workouts like Pilates is essential to ensure that you use the correct muscles without getting injured. Contact information for each of the major programs in this chapter is provided in Appendix A. Still, when in doubt, ask about a teacher’s credentials. It takes several hundred hours of teacher training to understand how to modify exercises for individual students. An experienced teacher is someone who can take your anatomy, injuries, and emotional makeup into account and make suggestions specifically for you.

Meanwhile, please avoid power sessions with even the most experienced teachers, whether the focus is on exhausting routines, sweltering heat, or extreme positions. Although it may seem as if you are getting a better workout, the point of cross-training is to enhance your fitness level without adding undue stress to your body. Needless to say, the floor also needs to be resilient if you are doing impact exercises, such as jumping.

What Constitutes a Good Workout?

Regardless of the type of activity, a solid program eases you into a routine, beginning with a slow five- to ten-minute warmup that gradually progresses into more evolved exercises, followed by the same amount of time cooling down. This approach protects you from the initial shock associated with any new activity. To help you progress, a program should also challenge your body by varying the content, intensity, and timing of exercises. Known as the overload principle, this method prevents your body from adapting to any one routine and becoming complacent. Here is how cross-training works.

Tip

Exercises that teach you to isolate specific muscles rather than gripping a whole area like the buttocks enhance the fluidity of dance movements.

Aerobic Conditioning

Most people know that cardiovascular fitness is good for the heart. Unfortunately, few dancers realize that it also helps them to perform for longer periods by reducing the buildup of lactic acid (or lactate), which causes a burning sensation and muscle fatigue. Dancing generally involves rapid bursts of high-intensity exercise that is time-limited, because your energy comes from the muscles’ carbohydrate or glycogen stores, not oxygen. Hence, the term anaerobic (“without air”) is used to describe dance. Technique class will not prepare you to work for an extended performance of Twyla Tharp’s nonstop choreography, for instance, In the Upper Room.

An aerobically fit dancer, in contrast, has a definite advantage. First, this form of exercise helps your body tap your carbohydrate stores more efficiently during sudden dance movements. It also conditions the heart to pump more oxygen to the working muscles. This can mean the difference between your heart rate beginning to return to normal within sixty seconds after a taxing variation and heavy panting for five minutes in the wings. This is true for all dancers, but especially if you are muscular with more fast-twitch muscle fibers that lack endurance. The fact that aerobic exercise also increases the diameter of the less bulky fast-twitch type A fibers, giving you a sleeker look, is an added bonus. Chapter 8 describes how all dancers can use endurance workouts to safely manage their weight. Still, the challenge is to know which workouts to choose, as well as the duration and intensity to get the best results.

The most straightforward approach is to do something that you enjoy, like the treadmill, and build up to a thirty-minute routine three times a week. The simplest, albeit less precise, way to gauge if your heart rate is sufficiently elevated while exercising is the talk test: You can talk but not sing or hold a conversation. You will definitely see an improvement in your stamina through regular exercise.

To achieve peak condition follow in the footsteps of Stella, a talented contemporary dancer. Knowing from past experience that many aerobic workouts place extra stress on the joints, she chooses to use the elliptical machine. This piece of gym equipment exercises both the upper and lower body for a great aerobic workout, while minimizing the physical impact on your joints. It’s also an excellent way to burn fat. In contrast, high-impact activities where you’re pounding the ground, like jogging or jumping rope, can cause overuse injuries, such as tendonitis. Other aerobic exercises can be problematic for different reasons, says Marika Molnar. The following list of common workouts gives you an idea of the potential negative repercussions for dancers.

• Riding the stationary bike with high resistance (10mph or more) can create bulk and back strain.

• Spinning on a stationary bike with no resistance can strain the kneecaps.

• Swimming in cold water can increase appetite.

• Jogging can strain the foot, ankle, and knee, especially with turnout.

• Power walking can place stress on the hips.

• Climbing stairs can exacerbate bad backs.

• Jumping rope can stress all the joints of the lower body.

Some dancers can do these activities without problems. For example, NYCB principal Yvonne Borree loves swimming, joking: “My friends say I look like a swan on the kickboard.” Abi Stafford uses the stationary bike with moderate resistance (less than 10mph). For dancers who use the bicycle and need to reduce strain on the lower back, consider working on the recumbent bike with an armchair-type design. However, if you do develop any untoward effects from an aerobic activity, please switch to a different workout.

In Stella’s case, she’s satisfied with the elliptical machine. Her goal is to develop an aerobic foundation by working at 75 percent of her maximum heart rate (MHR) three times a week for thirty minutes over the next two weeks. This number will vary, depending on your age and gender (see box on the next page). Stella programs the machine at her gym to monitor her target heart rate as a twenty-year-old woman: 154 beats per minute. Of course, Stella can check her pulse by following the procedure in the box, or order a sports bra with a built-in heart monitor and a stopwatch at www.numetrex.com.

The next step for Stella is to gradually replace two of her steady routines with interval training, alternating a two-minute high-intensity workout at 90 percent MHR (185bpm) with a two-minute moderate rest period of 65 percent MHR (134bpm). This type of training, which mimics dancing, helps her heart rate drop even more quickly after a burst of intense activity while providing more power for strength and endurance.

% Maximum Heart Rate (MHR)

Subtract age from 226 for women and 220 for men. Multiply this number by a specific percentile to get your target heart rate. (For example, to calculate 75 percent MHR, multiply by 0.75.)

Count Your Heart Rate

Press three middle fingers on the wrist of the other hand beneath base of the thumb. Count the number of beats for ten seconds watching the second hand on a clock and multiply by six to determine beats per minute (bpm).

The last form of conditioning involves sprinting, which is not really aerobic but helps build even more stamina for three-minute dance variations and other athletic choreography. It is one way to move from an aerobic foundation (continuous) and power (interval) to recovering even faster from high-intensity bouts (sprinting). This activity alternates thirty seconds of working to your absolute limit in any workout with ninety seconds where you stop and rest. Unfortunately, this isn’t the right activity for Stella’s naturally muscular body. A single bout of sprinting causes the body to release significant amounts of human growth hormone, which remains elevated for as much as two hours. The good news is that underdeveloped dancers can use three twenty-minute weekly sessions of sprinting to increase muscle mass. Just ease into it.

In summary, for most dancers it is sufficient to lay a sound aerobic foundation with continuous training three times per week for thirty minutes at a moderate level of intensity (75 percent of maximum heart rate). The choice of exercise depends on your schedule, motivation, and physical needs. As with all cross-training (endurance, strength, and flexibility), it will take at least six weeks to get into peak condition.

Strength Training

The other part of the picture is strengthening your muscles to help you move more easily without unnecessary effort, while maintaining your speed and range of motion. Body type will obviously come into play, as a loose-jointed dancer will benefit from different exercises than one who tends to be tight. Rehabilitating prior injuries is equally crucial, as Megan LeCrone discovered when she sprained her ankle for the second time after joining the company. A physical assessment by a dance medicine specialist, such as a physical therapist, can give you instant feedback about an appropriate exercise program by using the fitness screening at the end of this book. For example, a number of NYCB dancers have discovered that they had unrecognized weaknesses and muscle imbalances or needed to strengthen one group of muscles to work better with another group.

At the same time, the most important aspect of a cross-training program (apart from a sprung floor and a good instructor) is a balance of stretching and strengthening. Although it might seem counterintuitive, each time you perform an exercise to strengthen a muscle, you also shorten it. Stretching is necessary to counteract this response. While dancers can do this on their own, Pilates and the Gyrotonic Expansion System cover both aspects of conditioning in a complete way. These programs address key areas like the abdominals, pelvis, and back (the core muscles), which support the spine, and the lower body, with particular emphasis on the foot and ankle.

They also tap into slow-twitch muscle fibers, which do not create extra bulk, according to exercise physiologist Dr. Mathew Wyon. Stella, our contemporary dancer, was happy to hear this. Her gynecologist had advised her to start a weight-lifting program to increase her bone density, which was slightly below normal because of primary amenorrhea (menarche after age fifteen). This menstrual problem arose from years of fruitless dieting to streamline her muscular build. It is reassuring to know that she can use light weights to help her bones, as well as strengthen her body, without jeopardizing her leaner look. Even better, she can eat three healthy meals plus snacks with some helpful guidance. She sought a referral from the American Dietetic Association (www.eatright.org) for a sports nutritionist in her area. Follow-up phone interviews allowed her to identify one who worked with dancers.

Male dancers often need to build muscle mass for partnering, as well as for aesthetics. Julian, who hopes to get hired for the annual Radio City Christmas Spectacular, uses his local gym to get access to dumbbells and heavy weights. He learns to stress various muscle groups, such as his upper body and the core muscles that protect his back, under the supervision of a personal trainer. While everyone has a different starting point, the goal is to increase the amount of weight lifted with each additional set. Dr. Lawrence DeMann from NYCB’s medical team offers the following example: “Let’s say for instance, you lift a weight of fifty pounds and you can do that ten times. By the time you get to ten it’s a little bit hard. The next set, you add ten more pounds, so you really can’t do ten repetitions. You’re struggling to do just eight. Then, the next set you add another ten pounds, so you’re now lifting seventy pounds and you’re struggling to do even five or six repetitions.”

Muscle gain requires that you fatigue as many muscle fibers as possible, because they strengthen and grow in response to stress. For the record, this does not mean overtraining, which is associated with impaired performance. Aim to lift weights four times a week with a day off between sessions. If you do not see improvement, cut back on regular aerobic exercise, as this workout burns extra calories in addition to speeding up your metabolism. Sprinting will help you consolidate your gains.

Regular strength training should be done at least twice a week. We do not recommend that teenage dancers use heavy weights during periods of rapid growth. It is also important to have appropriate supervision. A personal trainer can help you develop a fitness program at your gym. Athletic trainers and physical therapists, in contrast, focus on injury rehabilitation and prevention.

Range of Motion Training

Stretching is an important part of maintaining your natural flexibility, which tends to decrease with age. However, there are periods when you need to back off, like adolescent growth spurts, when you temporarily lose flexibility as your bones shoot up while your muscles, ligaments, and tendons lag behind. Carol is a sixteen-year-old ballet student who thought she was losing her talent when she grew almost four inches in a year. Rather than back off, she would sit in a side split for an hour in front of the television until she eventually tore some muscle fibers in her adductors (the muscles on the inside of the thigh). This is a serious injury because the damage creates a tight band of scar tissue, which she now has to deal with in physical therapy.

The best time to stretch is when you are warm, preferably after dance class as part of cooling down. Yet be aware that your muscles are also fatigued, so take it easy by following the instructions for static stretching in Chapter 5. In addition, stretching is not a competition between you and the most loose-jointed dancer in your class. Instead, keep the focus on your own needs and capabilities, stretching each of your major muscle groups to the point of mild discomfort, knowing it’s not how hard you stretch but how often.

There are also distinct disadvantages to long stretches (more than thirty seconds) before you dance. A study in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise by Canadian researchers at the Memorial University of Newfoundland shows that students who warm up on the stationary bike for five minutes and stretch their legs to the point of discomfort, maintaining three different static stretches for forty-five seconds each, do not do well. This is true even though they only repeat the stretch three times, with fifteen-second rest breaks. The results indicate a significant decrease in their balance, reaction time, and movement time, compared to a group that did not stretch and rested after cycling. The authors speculated that stretching may change muscle compliance or the tendency to yield.

Thus, stretching is a double-edged sword. Dancers must lengthen their muscles to avoid pulls and tears due to tightness. However, it is necessary to do it correctly by following general guidelines for stretching different muscles. For example, it is important to stretch the hamstrings and the quadriceps, which are your primary muscles for locomotion. Called antagonistic muscles because they either raise the knee up or curl the leg back, they tend to be extremely unbalanced in terms of strength. By properly stretching the weaker hamstrings, you are less likely to overload them with your more powerful quadriceps. It is also crucial to stretch the calves, the iliotibial band along the outside of the thigh, hip flexors, chest, and front of the shoulders. For details, check out Stretching by B. Anderson (details are in Appendix A).

Choosing a Strengthening and Stretching Program

Because there are so many programs to choose from, the pressure to find the right one can feel overwhelming. By far, the most popular conditioning programs among dancers are Pilates, Gyrotonic, and yoga. All three are considered mind-body methods, because of the high level of mental concentration required. They also emphasize breathing, postural alignment, balance, coordination, and imagery (visualizing your spine as a strand of pearls as you roll back down from the sitting position to the floor, for example). Some performers focus on a couple of different programs; others switch from one to another. To see improvement, you need to take two to three classes a week under the guidance of an experienced teacher.

Pilates

This unique workout is an excellent start-up program for most beginners because it works in a linear progression, with both sides of the body moving in unison. It is also a favorite among professional dancers like Abi Stafford, who continued to use it after her ankle surgery to retain extra strength and flexibility. Other dancers, like eighteen-year-old Karen, find it quite helpful during their growth spurts as a way to stay in shape, rather than pushing too hard in dance class. The Pilates technique also allows ballet dancers to exercise in their position of function (that is, turned out).

Devised by German gymnast Joseph Pilates in the 1920s, this program was a well-kept secret in the dance world long before Hollywood discovered it in the mid-1980s as a way to develop an ultratoned body—without having to go for the burn. Pilates (pronounced pul-LAH-tees) appears deceptively easy. It provides incredible core strength in the abdominals and lower torso, the “powerhouse” of the body and the foundation for every movement, with a combination of yoga and calisthenics. Deep concentration and rhythmic breathing are emphasized. Gentle stretching accompanies each strengthening exercise.

The two main components of Pilates exercises are matwork, involving a series of calisthenic exercises performed on a padded mat, and machines, using springs, ropes, slings, and pulleys for additional resistance. Although the matwork is often taught separately today at gyms, you will achieve the best results if you practice both in one session. The machines ease you into some of the more complex movements, taking you to a whole new level, where you work on all the muscle groups. Color-coded springs make it easy to adjust the level of resistance, which can change the difficulty of the exercise. This makes it easier to go through a full range of motion, such as leg circles, where you both stretch and strengthen the limbs.

Pilates instructor Deanne Lay believes in the many benefits of this type of conditioning. However, she says, “These can be outweighed if your placement is off. It needs to be taught correctly from the beginning, so that you learn the right movement patterns.” A good example is the focus on the “neutral spine” (the natural arch under the lower back), which is based on medical knowledge over the last decade due, in large part, to input from physical therapists who use Pilates during rehab. Marika Molnar explains: “The danger of the flat back is that it puts a lot of pressure on the lower discs and joints. With the neutral spine, you’re in a better place to work your deep abdominals that stabilize the back and prevent injuries.” To locate a qualified practitioner, contact the Pilates Method Alliance.

Gyrotonic

Another popular conditioning program is Juliu Horvath’s Gyrotonic Expansion System, which uses many of the same principles as Pilates. In fact, certain dancers find that these conditioning programs complement each other. The main difference with Gyrotonic is that the machines are inspired by Horvath’s deep interest in yoga. As a former ballet dancer in Romania, he prefers to work three-dimensionally on the body in circular, spiraling movements that span multiple joints and also allow for turnout. The result is that the left and right sides of the body work independently at the same time, using pulleys that are connected to separate weight sources. Dancer Wendy Whelan prefers using this asymmetrical approach because of her pronounced scoliosis; she found that Pilates, which worked both sides in unison, was painful.

As with Pilates, the origin for all movements in Gyrotonic stems from the core abdominals. In addition to working both sides independently, you focus on the upper and lower body. Some dancers find this dual emphasis places undue stress on vulnerable areas. Others, like Wendy and Megan LeCrone, who also switched from Pilates to Gyrotonic, find that the extra focus on movement is a liberating experience. “It helped me to know when to use my strength and when not to,” Megan says. “I felt a greater awareness about my body while I was moving.” Yet the ultimate test is how a program or specific exercise feels to you, regardless of what works for someone else. If your back starts to hurt, for example, it’s time to have a discussion with your teacher about eliminating exercises or changing your approach. Both teacher and student need to be open to feedback in a healthy cross-training program.

It is best to ease into a new routine. In this case, the floor version of Gyrotonic without machines is called Gyrokinesis, which simulates movements on the machine on your back, stomach, and in seated positions. Michelle, a twenty-seven-year-old musical theater dancer, likes it because it focuses on stretching and strengthening movements, frees up her joints, and improves coordination. She also uses some of the movements to warm up for dance class and performances, whereas Abi uses Pilates matwork. For referrals, check out Juliu Horvath’s studio information on the general Gyrotonic Web site at www.gyrotonic.com.

Yoga

In India the Sanskrit word yoga refers to bringing mind, body, and spirit together as a way to enlightenment. It’s up to you to choose whether to make it a way of life or simply a form of exercise. The traditional form, called hatha yoga, has become associated with the asanas, or postures, considered to be fitness exercises for many people in the West. Traditional yoga is a set of sequences, including breathing exercises, that improve strength, flexibility, and physical well-being. Megan, who has struggled with perfectionism, says, “I now do breathing exercises from yoga before a performance. You have all that adrenaline, knowing you have to go onstage. But instead of playing with my pointe shoes, costume, and headpiece, I do ten deep breaths in and out. I use yoga to calm down.”

Hilary Cartwright teaches Yoga for Dancers, a class that also emphasizes breathing and is especially suited for performers (see www.hilarycartwright.com). The class doesn’t begin with extreme positions, but builds up to more difficult movements like a dance class. Some steps are also done in a mini turned-out position, because it is more dancer-friendly than standing with the feet parallel. “It’s not about how big the back bend is or how deep the stretch,” says NYCB corps dancer Dena Abergel, “but strengthening your core muscles to create fluid movement.” It isn’t power yoga, which often forces dancers into extreme positions that may create injuries. While Yoga for Dancers is mainly available in New York City, traditional hatha yoga with an experienced teacher is a safe and reliable option for dancers outside of New York. Find out more about your yoga options by checking out the yoga Web sites featured in Appendix A.

Weight Training

As we have already learned, using weights is an essential element of building muscle strength. While it’s a good idea to work out a program with professional guidance, these are a couple of examples of working your upper body. The goal for each of the following exercises is three sets of ten slow repetitions, three times per week. It’s always important when standing to relax the knees and contract the abdominals to support your spine. Pick a manageable but challenging weight to avoid injury.

For example, Melissa, an aspiring tap dancer, uses a three-pound weight in each hand to do bicep curls, holding her arms straight in front of her with palms facing the ceiling, shoulder-width apart and perpendicular to the floor. She then curls her arms toward her chest and lengthens them back out for her set repetitions. Next, she works on her deltoids (the front, side, and back of the shoulders), extending her arms straight in front, palms facing each other at shoulder height. She holds them there for a moment and slowly lowers her arms back down to her side for each set. Melissa does the same exercise taking her arms out to the side up to shoulder height with palms facing down before lowering them to her start position. She completes the last deltoid exercise by raising her arms straight back aligned with the shoulder joint, going only as high as she can before bringing them back down. (Note: If you don’t have dumbbells, you can use ankle weights instead.) A professional, such as a Pilates instructor or a personal trainer, can provide a full set of upper-body exercises.

Impediments to Cross-Training

By now, I hope that the benefits of improving strength, flexibility, and aerobic capacity are evident in terms of their positive impact on your dancing. So what holds many dancers back from adding them to their routine? I’m afraid some of it has to do with the difficulty of changing ingrained habits even if it helps you get to the next level in your career. Traditionally, dancers have always relied on class to prepare them for the stage. Many of their teachers still believe that hard work is sufficient, since they relied on class as well. There is also the idea that dancers are artists, not athletes. Yet change is in the air. Many schools have begun to add cross-training to their curriculum, breeding a new generation of savvy dancers who are comfortable going to the gym or seeking out other ways to improve their overall fitness. Thus, while the more seasoned professionals may be sticking to their old routines—at least until they get injured—young dancers are more open to change if it will help them achieve their goals.

At the same time, dancers need to use cross-training realistically in their professional life. Do more during the layoff to stay performance-ready, but cut back during the season. Abi Stafford agrees, saying, “I don’t do a whole lot at the gym or Pilates when I’m performing because it’s too much. But I miss it.” It’s fine to combine cross-training with daily technique classes if you feel up to it and your dance schedule does not exceed five hours per day. Otherwise, you may set yourself up for an overuse injury. In a survey of five hundred injury reports, 79 percent occurred after the fifth hour of dancing. A well-paced conditioning program can use cross-training in addition to dance classes for getting back into shape.

Getting Fit for Dance

Cross-training can help you in various situations both during and after the season or for an intense summer program. However, it works best when you are rested and need to get ready for a demanding dance schedule. Here is a case study of a professional dancer who used it to prepare for rehearsals and performances.

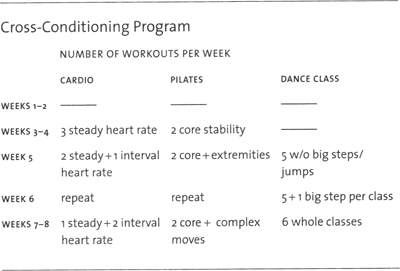

Amanda is a young modern dancer who has just returned from a long, tiring tour. She hopes to regain her energy over an eight-week break by sleeping ten hours a night and letting her mom prepare her favorite home-cooked meals. Two weeks go by before she even considers doing any kind of exercise. Fortunately, her company’s physical therapist has provided helpful suggestions about easing back into dance. Amanda decides it’s worth a try. This is only her first year as a professional dancer and she wants to return to the company in peak condition. Here is her program (see table).

The first two weeks of exercise (weeks 3 and 4 of her eight-week break) start off with three weekly sessions on the stationary bike. She stays within a moderate rate that’s less than 10mph, bringing her up to 75 percent of her maximum heart rate for thirty minutes. This provides an aerobic foundation. Amanda also adds two weekly Pilates sessions, focusing on core stability (abs, pelvis, and lower back) and motor control to establish correct alignment in preparation for more complex exercises that lie ahead.

The next two weeks (weeks 5 and 6) Amanda replaces one steady aerobic workout with one interval training routine where she alternates between 90 percent and 65 percent MHR. She adds simple arm and leg movements to her Pilates sessions, such as leg circles, while continuing to stabilize her core. This is also the time when she brings in one dance class, five days a week, omitting big jumps, partnering, and complex combinations until week 6 (see below).

The last two weeks (weeks 7 and 8) include one steady and two interval aerobic workouts, and two Pilates sessions with complex exercises, such as stabilizing the pelvis by raising it off the mat in a bridge while lying on her back, extending one leg out and in, with a repeat to the other side, and rolling down. She completes six weekly dance classes, working full-out. All of this helps her focus physically and mentally in preparation for going back to work.

In contrast to professional dancers, Joe is a student who plans to take a summer intensive in July and return to his old dance school in September. He will need to rest for at least two weeks in August. He can then alternate cross-training with a modified dance class in the third week, before gradually working up to five or six full dance classes in the last week prior to returning to his regular dance program.

Cross-training is proving to be beneficial for dancers in every genre, beginning in adolescence when most injuries first occur. However, you need to find the right workout, pace yourself according to your needs, and have proper guidance. It is equally important to enjoy your workouts and have fun. Remember, even adding a little more exercise at a time will really help your dancing.