This section explores the many ways Wikipedia pages are grouped together. For example, pages can be grouped in the following ways:

Informally by topic

By date

Into hierarchical taxonomies (categories)

By format (for example, you can browse only high-quality featured articles)

Any way you like! If you follow links from one article to another, you create your own "group" of articles—your own personal story.

Written language has been around for thousands of years, but its format has changed many times. Stone carvings were expensive and time consuming (and decidedly nonportable) and were, therefore, used mostly for official state purposes. Medieval scholars wrote on valuable animal skins, which they periodically scraped clean and covered with new text. The printing press made written texts easily affordable and accessible.

Writing is circulated today in many formats, and each format has its own way of doing things. For example, newspaper articles are worded tightly to cut down on printing costs, and the most important information is placed at the beginning of the article so that you can conveniently stop reading at any point.

If you're an adult, books are second nature. Certain assumptions, such as the fact that the pages of a novel appear in a particular order or that the millions of extant copies of Sense and Sensibility all contain essentially the same text, are so ingrained that they hardly seem worth mentioning.

But Wikipedia violates many of these assumptions. It is a new medium, with its own strengths, weaknesses, and conventions.

The most striking feature of the World Wide Web—and of Wikipedia—is the link: text that takes you somewhere else and is traditionally underlined and colored blue. Early information theorists called links hypertext, and the term has become a catchall for the ways in which the Internet is different from the printed word.

What does hypertext mean on Wikipedia?

Wikipedia articles can be read in any order.

A Wikipedia article need not be read "cover to cover." In a single browsing session, you can read ten different paragraphs from ten related articles; indeed, this grazing approach is often the best way to gather information.

Wikipedia articles can be grouped in many ways, and these groups can overlap.

More generally, hypertext means that every page on Wikipedia references (links to) other pages—and of course, every page is linked to by other pages. Understanding how Wikipedia pages are linked to one another is key to browsing Wikipedia.

Because there are so many ways to explore related topics, Wikipedia is great for getting up to speed about subjects you don't know well—even areas in which you don't know what you don't know. (A search might lead you to a particular article, but that article itself can become a jumping-off point to another topic.)

There are three types of links on Wikipedia.

Internal links don't always have the exact title of the page they're linking to; any text can link to any page, which is occasionally confusing. For instance, clicking a bluelink that reads Samuel Clemens might take you to the page [[Mark Twain]] (and your reaction might be "Huh?" "I knew that, I suppose," or "Of course!").

Using the Random Article link is fun, but if you have work to do, you need a way to find specific articles (unless your research area is the dynamics of online encyclopedias). Using search is the best-known way to find Wikipedia articles, but other ways to inform your understanding of a topic exist. For example, you can

Most Wikipedia articles have traditional paragraph structures, but some take the form of lists. Each list item usually links to its own article. Thus, each list becomes a miniature index to its own topic area.

Wikipedia is pieced together collaboratively, bit by bit. It relies on contributors bold enough to slide new information into a complete-looking article. In this context, lists can feel particularly welcoming to new writers: After "This is a list of items" and "This list was written by a bunch of different people," the next logical thought is often "I can add another line item to the end of this list."

Consequently, lists abound throughout Wikipedia, indexing a staggering array of topics. Some are well maintained and quite complete, others more informal and amateurish. Sometimes they define an unexpected topic, such as [[List of songs about or referencing Elvis Presley]]), or provide a new view of a familiar topic, such as [[List of accidents and incidents on commercial airliners grouped by location]]. Smaller lists also exist within ordinary, paragraph-style articles.

Note

Lists help Wikipedia expand because they encourage the creation of redlinks—links to articles that haven't been written yet.

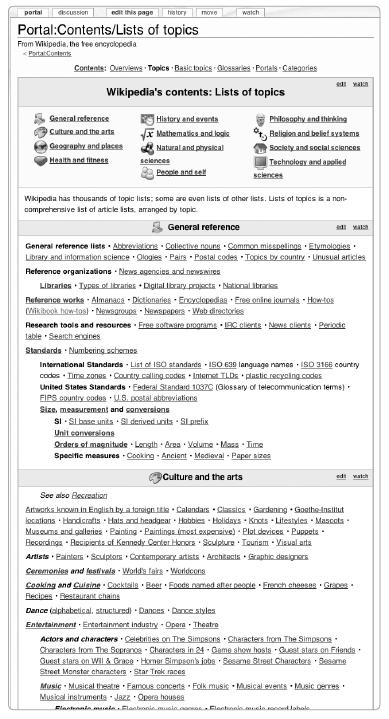

Of course, lists can be grouped. They can be organized chronologically, by theme, or by annotation. Many lists are accessible through the main contents page, which is linked on the global sidebar. Some of the links available from the contents page include the [[List of academic disciplines]], which provides a list of broad overview articles by academic discipline (such as engineering); these articles in turn link to more detailed articles. The [[List of overviews]] has a similar function: It presents a number of articles in a subject area (philosophy, for example) that give a survey of that area. The top-level page for lists is the Lists of Topics page, which is a directory of list articles.

One interesting way to proceed from a list is to click Related Changes in the left sidebar. Related Changes is a list of recent changes to any articles that the current page links to, which, in the case of a list article, includes all items in that list. If you're seeking editors working in your field of interest, this is one way to make quick contact.

You do have to filter out some noise: Related Changes shows changes to all pages linked to from a given page. If you apply it to [[List of glaciers]], you may find edits to [[Glacier]], [[Sierra Nevada]], or [[Mount Kilimanjaro]], alongside edits to less relevant articles such as [[Argentina]] and [[2007]]. For certain lists, Related Changes is an impractical way to proceed.

New lists are created all the time. But some existing lists are being phased out in favor of categories (a more rigid, automated classification scheme; see "Browsing by Categories" on Summary).

A great deal of debate has surrounded the relative merits of categories and lists. Lists can be annotated, reverted to older versions, and peppered with references. Categories, on the other hand, are more automated and thus work better with really large collections of pages.

If you're feeling nostalgic, you can browse Wikipedia using traditional library arrangement schemes: the Dewey Decimal Classification and the Library of Congress Classification. These schemes might seem archaic, but because they were designed to organize broad arrays of human knowledge (and secondarily to sort books), they can be interesting to browse.

See [[Library of Congress Classification]] for the top level of the classification. If you click one of the 21 linked articles, you'll drill down into the next level of classification, with topics linked to the appropriate articles. [[Category:Library of Congress Classification]] also lists the breakdown by letter codes. The article [[List of Dewey Decimal classes]] gives the first three digits of the Dewey class, with some topics linked to those articles.

Further, you can find an outline of Roget's Thesaurus, with appropriate articles wikilinked, at [[Wikipedia:Outline of Roget's Thesaurus]].

There are a wide variety of date- and time-related articles that list significant events during a particular date, year, or even century.

Articles exist that summarize the following:

Every year between 1700 BC and the present (see [[List of years]])

Every decade between the 1690s BC and the 2090s AD ([[List of decades]])

Every century between the 40th century BC and the 31st century AD ([[List of centuries]])

Every millennium between the 10th millennium BC and the 10th millennium AD (see [[List of centuries]] again)

Every geological division, epoch, period, and era (see [[List of time periods]] for these and many more)

Simply type a year in the search box or go to one of these lists.

As you might expect, the quality of these articles vary widely, usually in predictable ways. [[Jurassic]], [[December 2004]], and [[1800s]] are detailed; [[1485 BC]] is not. In general, the less-detailed articles are scattershot collections of factoids. If you're unsatisfied with a yearly article, move up to the decade or century level.

For most modern years, such as 1954, dozens of dedicated articles exist—for instance, [[1954 in architecture]] or [[1954 in baseball]]. However, 1954 in cricket is a category rather than an article, and if you want to learn more about crime in 1954, you might look at [[FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives by year, 1954]]. The overall [[Category:1954]] is the right place to start for intensive research, as it collects all these articles in one place and numerous subcategories will point you in the right direction.

Note

Year articles take precedence over other articles that might have numeric titles. For example, if you go to the article called [[137]], you get an article about the events occurring in the year 137 AD. As it happens, 137 is an interesting number in physics, but to read about that you should go to the article [[137 (number)]].

You can also find an article for every date from [[January 1]] to [[December 31]]. These are lists of anniversaries, not articles specific to a given year. They convey the significant events, births, and deaths for any date, such as January 20th—helpful, perhaps, for college students looking for a party theme. These lists populate the On this day … section of the main page. (The title convention is simply the month and day number, or April 1; no suffix is required for ordinals.) [[List of historical anniversaries]] is a handily arranged list of all these pages.

Note

If you ever find it too tiring to work out 20th century dates in Roman numerals, such as those you might find in old copyright notices, copy the letters (for example, MCMLXVIII) into Wikipedia and let a redirect take the strain.

Decade articles are in a familiar form: the first year of the decade plus s (for example, [[1660s]], no apostrophe). Again, [[List of decades]] is a handy list with coverage stretching from the 17th century BC to the 21st century AD.

Century articles are found in either the form [[18th century]] (for centuries AD, you can leave out the AD) or [[2nd century BC]] (for centuries BC). The Common Era convention of writing BCE and CE, as many scholars do, is also supported and used within Wikipedia, coexisting with BC/AD (refer to [[Common Era]] for background); date links using this convention will redirect to the proper articles. (If you're really clever, type 0 AD into Wikipedia. Go ahead!)

These by-date articles stretch not only into the past (there is a century article for [[40th century BC]], before which Wikipedia only has articles for millennia), but also into the far future. These future year articles record not only future anniversaries and future astronomical events, but also fictional events that are supposed to have happened in these years. (In the [[25th century]] article, for instance, we are reminded that Buck Rogers lived around 2419.)

Timelines provide detailed chronologies for various topics. The [[List of timelines]] lists timelines covering hundreds of topics, offering detailed perspectives for understanding history. If that's not enough, the [[Detailed logarithmic timeline]] and its linked pages could claim to be an education in itself.

Another way to find articles is to browse through categories. Categories, like lists, collect related articles. But although Wikipedia's software treats a list the same way it treats any other article, it treats categories differently. In order to place an article in a category, an editor does not edit the category's page. Instead, the editor adds a specialized tag to the article itself, and the MediaWiki software automatically populates the category page with every article tagged as a member of that category.

Alongside links and templates, categories help provide structure to the wiki. In every topic area, categories are created and used to group related pages together: For example, [[Category:American novelists]] contains thousands of articles about authors, for those interested in exploring American literature. In an area where you already have some expertise, the category system may be your best bet for finding content of interest.

The categories in which an article has been placed are listed at the very bottom of the article page, underneath the article text, in a small shaded box (Figure 3-9). Each category name is a link: Click one to visit the corresponding category page, which lists all the articles in that category.

Figure 3-9. The category listing at the bottom of an article, showing the categories in which an article appears: These are the categories for the article [[Exploding whale]].

A page can be placed in any number of categories; indeed, most articles are in more than one. No category excludes any other, and categories can even be placed inside other categories, which can themselves be placed inside other categories! This creates a tree structure (or a taxonomy, if you prefer). For example, the article [[Malta]] is in [[Category:Malta]], itself in [[Category:European microstates]], which is in [[Category:Microstates]], which is in [[Category:Countries by characteristic]]; this is then categorized under the broad category of [[Category:Countries]]. Browsing successive layers of subcategories is a useful way to find content: You can get to a high-level category any way you like and then drill down into a more specific area. Because Category is also a Wikipedia namespace, you can go directly to a category using the search box, for example, [[Category:Poets]].

Categories may be surprisingly specific as well as sweepingly broad. Some are just fun: [[Category:Toys]] has as subcategories [[Category:Toy cars and trucks]] and [[Category:Yo-yos]], whereas [[Category:Teddy bears]] is one subcategory of [[Category:Fictional bears]].

Everyone is welcome to categorize pages as needed, either by placing an article in an existing category or creating an entirely new category (see Chapter 9). As with every type of content, guidelines for creating and placing categories have been established. See, for example, [[Wikipedia:Naming conventions (categories)]] (shortcut WP:NCCAT).

When you click a category name from the linked categories at the bottom of an article, you are taken to a category page located in the Category namespace. These pages are divided into four main parts (Figure 3-10):

The top part describes the topic. This section is editable and may contain wikilinks to relevant encyclopedia articles. This section is not always present.

The second part lists the immediate subcategories of the category. For example, [[Category:American crime fiction writers]] is a subcategory of [[Category:American novelists]]. This section is only present if the category contains subcategories.

The third part of the page displays an automatically generated, alphabetical list of wikilinks to the articles in the category. This list is the heart of the category page—it is always present and is usually the section that proves most useful. A category can contain any number of pages; some contain thousands. It would be impractical to display such a large number of links on one page; on Wikipedia, a category page will only display as many as 200 links at a time, sorted alphabetically. Click the Next 200 link to jump to the next page of links.

Note

Alphabetical order is not always obvious: Articles about people, for example, are normally best sorted alphabetically by surname. However, if the correct sort tag hasn't been added to the biography, it will be alphabetized conventionally (i.e., by the first word in the page title, which is often the first name of the person). Details on sorting are in Chapter 9.

The last part of the page shows supercategories—the categories that this category belongs to. These categories appear in a shaded box named (somewhat confusingly) Categories, just like the categories for articles.

Figure 3-10. Example of a category page (the category of Fictional Countries), showing editable sections

Categories form a kind of parallel Wikipedia universe. If you're lucky, a small cluster of categories will cover just the articles you're seeking. Think of subcategories as being under a category, and you'll appreciate that clicking can take you both "up" (to a more comprehensive category) and "down" (to a more specialized category). You can move to a category of greater scope and generality or (conversely) narrow things down.

Therefore, the other significant part of a category page is the list of categories to which the page belongs, in other words, the supercategories for which this category is a subcategory. These are your ways inside the category system.

Up-and-down navigation is a very handy way to move from a related article to the one you really want. For example, you can move from a place in the right state but wrong county to a category of places in the state to a subcategory of places in the right county, where you'll find the title of the article you want. That journey is like going in and up and then down and out of the category system. Most browsing using categories requires a combination of navigating up (to a more comprehensive category) and down (to a subcategory) in search of the category of greatest interest, followed by a systematic search of pages in that category.

The article about the ocean sunfish (which is also known as the Mola mola) might be placed in the Molidae category, for the fish's scientific family name (Figure 3-11). Looking at the category page for Molidae displays the other species in this family (as long as those species have properly categorized articles).

Figure 3-11. The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) or common mola is the heaviest bony fish in the world, with an average weight of 1,000 kilograms. The species is native to tropical and temperate waters around the globe. (From [[Mola mola]], image from NOAA)

Navigating from this category, you may go up, down, or out to one of the linked pages. [[Category:Molidae]] is a subcategory of [[Category:Tetraodontiformes]]. If you're interested in the biology of related fish, click that link. Once there, you'll see various families of the order Tetraodontiformes (such as the Puffers) listed as subcategories. This category system follows standard scientific classification.

You can eventually get to [[Category:Water]] from the fish articles. Using a less-than sign (<) to mean "clicking up to the next category," here is the chain of subcategories:

Ray-finned fish < Bony fish < Fish sorted by classification < Fish < Aquatic organisms < Water

Tetraodontiformes is one of more than 50 subcategories of [[Category:Ray-finned fish]]. Going from [[Category:Water]],

Water < Inorganic compounds < Chemical compounds < Chemical substances < Chemistry

to find out where [[Category:Chemistry]] fits in, look at

Chemistry < Physical sciences < Scientific disciplines < Academic disciplines < Academia

Is there no end to this? Actually, keep clicking through categories:

Academia < Education < Society < Fundamental

and you end up here:

Fundamental < Articles < Contents

The [[Category:Contents]] is the top category of all categories.

This non-serious exploration makes a serious point: Wikipedia not only brings knowledge together, it also classifies it. You can find an exhaustive, unwieldy list of all categories at [[Special:Categories]], or try [[Wikipedia:Categorical index]] for an arrangement by topic.

The highest levels of categorization are so broad that they are usually impractical even as starting points. But they do provide a novel way to sort content from a distance, as Robert Rohde did in some statistics from October 2007.[19] Programmatically tallying the articles in the broadest categories (and their subcategories), he was able to estimate the composition of Wikipedia itself: 28.0 percent science, 10.5 percent culture, 16.0 percent geography, 6.3 percent history, 0.8 percent religion, 5.5 percent philosophy, 1.8 percent mathematics, 14.3 percent nature, 6.0 percent technology, 1.4 percent fiction, and 9.6 percent general biography. These categories are, of course, fluid and negotiable (for example, the Politics category is inside the Philosophy category).

You can also browse by article type rather than by topic.

Perhaps you want to read only the very best Wikipedia content. In this case, browse the Featured Content portal at [[Portal:Featured content]], which includes all types of content (including articles, images, and portals) deemed to be the best Wikipedia has to offer.

Featured articles, available directly at [[Wikipedia:Featured articles]] (shortcut WP:FA), have been vetted, reviewed, and voted on by community members. They meet high standards of completeness, accuracy, and referencing, and represent some of the very best articles available on the site. Try your hand as a critic at [[Wikipedia:Featured article candidates]] (shortcut WP:FAC). Good articles are articles that may not be as extensive as featured articles but are still excellent quality; you can browse a collection of these articles at [[Wikipedia:Good articles]] (shortcut WP:GA).

Featured lists can reveal odd Wikipedia content. Whereas a list page taken at random from Wikipedia will (at most) have some navigational value, a featured list such as [[List of Oz books]] will have a good lead section, images, and much greater credibility. See [[Wikipedia:Featured lists]] (shortcut WP:FL) for several hundred featured lists.

Articles of poor quality or in need of attention are also collected in maintenance categories, such as [[Category:Cleanup by month]]. Another quick way to find articles with problems is to search for misspelled versions of commonly misspelled words in order to find errors and typos to correct, or (perhaps more interesting) search for dead-wood phrases such as "it is important to remember that," which can be replaced with more precise wording. The project page at [[Wikipedia:Cleanup]], where you can add articles you find with problems, also provides a quick way to start getting involved. Finding poor-quality articles and systemized maintenance work will be covered thoroughly in Chapter 7.

Apart from text, images are the most common and important kind of media used in Wikipedia. They help bring the encyclopedia to life, showing places and people, plants and animals, book covers, and machinery types. They illustrate processes and diagram complicated procedures and systems. They include logos, trademarks, heraldic devices, and flags. You can also find large numbers of maps.

To find some of the very best images on Wikipedia, visit the list of featured images at [[Wikipedia:Featured pictures]] (shortcut WP:FP). There is also a link from this page to a category on the Wikimedia Commons for featured desktop backgrounds, or pictures whose aspect ratios are suitable for wallpapering your computer desktop. You can find some lovely images here.

To browse for other images, go to the Wikimedia Commons, where images are organized by category. The Commons is actually designed as a repository of media and images that all the Wikimedia projects can use and link to. Thus you may find images, for instance, that are described in languages other than English. More on searching the Commons is in Chapter 16.

Every media file found on Wikipedia is intended to illustrate an encyclopedia article, not to stand alone. Wikipedia and the Wikimedia Commons offer a range of these files, from short animations to sound recordings. For instance, in the article about Mozart, you'll find a list of a few dozen or so audio files; these are short excerpts of his works for illustrative purposes. All of the media files in Wikipedia should be freely available under the GFDL license.

Like images, finding media files is a bit easier on Wikimedia Commons than on Wikipedia itself; on Commons, you'll find categories for sounds and videos, subcategorized into animations, animal sounds, and so on.

Again, just as for images, each file has a description page. Confusingly at first, these pages are all within the Image namespace; Wikipedia does not separate different media file types into different namespaces.

To play media files, you can try Wikipedia's embedded media player, which will play media files in your web browser. Simply click the Play in Browser link next to the file icon. Alternatively, you can download the file. However, playing it may present some obstacles as you may need to download special software. The major sound file type used on Wikipedia is the audio format Ogg Vorbis, whereas video files use the Ogg Theora format. These formats are broadly similar to others used to play digital audio and video, such as MP3 and MPEG, and can be played on almost all personal computers. Unlike MP3, QuickTime, and many other common formats, however, Ogg formats are completely free, open, and unpatented. Microsoft Windows and Mac OS X computers do not support Ogg formats by default and require additional software to play them. If your computer does not automatically play these files when you click them, you'll need to download and install free software from the Internet to play them. Go to http://www.vorbis.com for links to versions of downloadable players or codecs suitable for common systems.

If you already have a media player such as Windows Media Player or RealPlayer, or iTunes for a Mac, you can first download the .ogg codecs—small programs that decrypt the format—for these players, which will enable them to play Wikipedia's files. For Linux/Unix users, many recent free Unix systems are able to play Vorbis audio without any new software; however, many media players are available if you don't have any audio software installed. [[Wikipedia:Media help (Ogg)]] has a list of the free players available for all systems and directions for downloading the Ogg codecs for other music players.

Music files may occasionally use the MIDI format (.mid or .midi extension). MIDI is usually playable without new software. Most computers have a MIDI-enabled player and sound card.

In addition to music files, a small but growing number of articles contain spoken versions of the article recorded in .ogg Vorbis format by volunteers. With the right player, you can listen to Wikipedia articles in your car! Go to [[Wikipedia:Spoken articles]], [[Category:Spoken articles]], and [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Spoken Wikipedia]] (shortcut WP:WSW) to find these articles.

[19] These figures are taken from an October 2007 post to the WikiEN-l mailing list: http://lists.wikimedia.org/pipermail/wikien-l/2007-October/083862.html

![The category listing at the bottom of an article, showing the categories in which an article appears: These are the categories for the article [[Exploding whale]].](tagoreillycom20090804nostarchimages315882.png.jpg)

![The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) or common mola is the heaviest bony fish in the world, with an average weight of 1,000 kilograms. The species is native to tropical and temperate waters around the globe. (From [[Mola mola]], image from NOAA)](tagoreillycom20090804nostarchimages315886.png.jpg)