IN CONTEXT

Chemistry

1661 Robert Boyle defines an element, laying the foundations for modern chemistry.

1754 Joseph Black identifies a gas, carbon dioxide, which he calls “fixed air”.

1772–75 Joseph Priestley and (independently) Sweden’s Carl Scheele isolate oxygen, followed by Antoine Lavoisier, who names the gas. Priestley also discovers nitric oxide, nitrous oxide, and hydrogen chloride, and experiments with inhaling oxygen and making soda water.

1799 Humphry Davy suggests nitrous oxide could be useful as an anaesthetic in surgery.

1844 Nitrous oxide is first used for anaesthesia by American dentist Horace Wells.

In 1754, Joseph Black had described what we now call carbon dioxide (CO2) as “fixed air”. He was not only the first scientist to identify a gas, but also demonstrated that there were various kinds of “air”, or gases.

Twelve years later, an English scientist named Henry Cavendish reported to the Royal Society in London that the metals zinc, iron, and tin “generate inflammable air by solution in acids”. He called his new gas “inflammable air” because it burned readily, unlike ordinary or “fixed air”. Today we call it hydrogen (H2). This was the second gas to be identified and the first gaseous element to be isolated. Cavendish set out to measure the weight of a sample of the gas, by measuring the loss of weight of the zinc-acid mixture during the reaction, and by collecting all the gas produced in a bladder and weighing it – first full of the gas, then empty. Knowing the volume, he could calculate its density. He found that inflammable air was 11 times less dense than ordinary air.

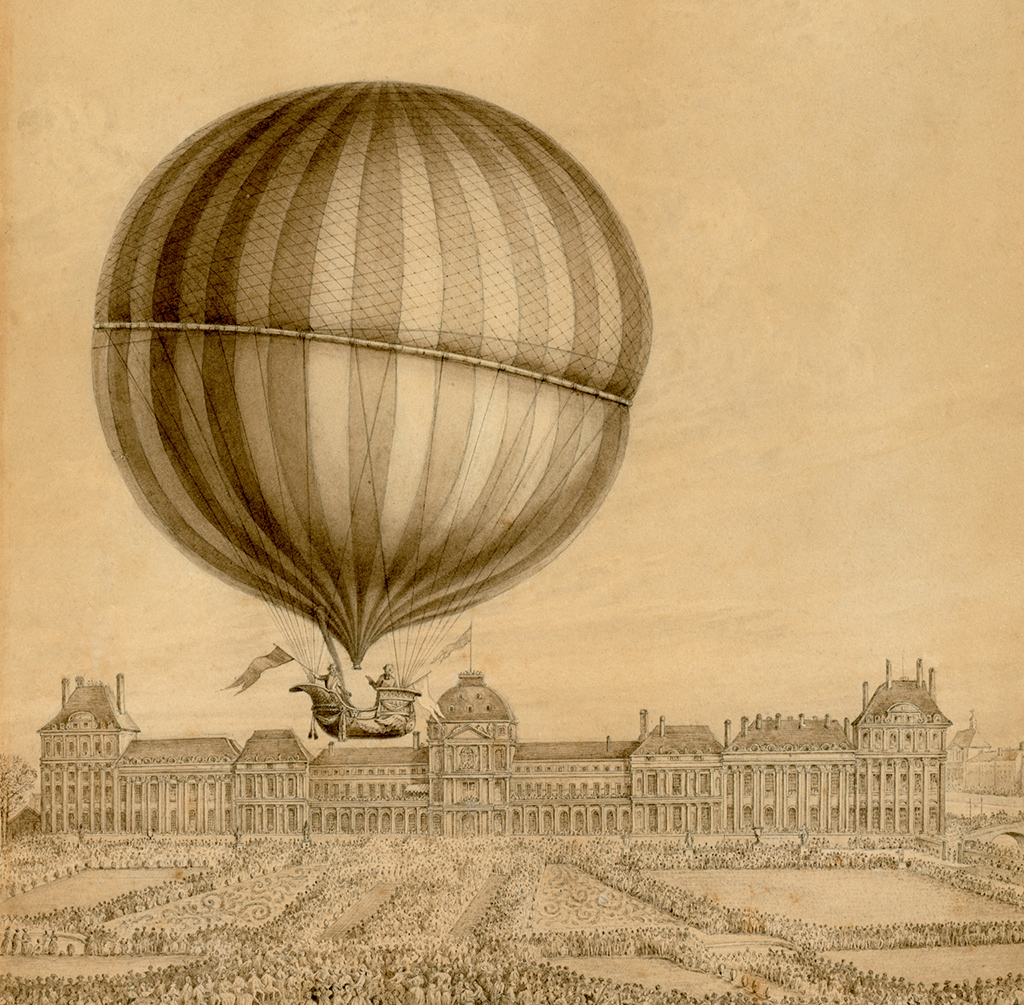

The discovery of low-density gas led to aeronautical balloons that were lighter than air. In France in 1783, inventor Jacques Charles launched the first hydrogen balloon, less than two weeks after the Montgolfier brothers launched their first manned hot-air balloon.

Explosive discoveries

Cavendish also mixed measured samples of his gas with known volumes of air in bottles, and ignited the mixtures by taking the tops off and applying lighted pieces of paper. He found that with nine parts of air to one of hydrogen there was a slow, quiet flame; with increasing proportions of hydrogen the mixture exploded with increasing ferocity; but pure, 100 per cent hydrogen did not ignite.

Cavendish’s thinking was still handicapped by an obsolete notion from alchemy that a fire-like element (“phlogiston”) was released during combustion. However, he was precise in his experiments and in his reporting: “it appears that 423 measures of inflammable air are nearly sufficient to phlogisticate 1,000 of common air; and that the bulk of the air remaining after the explosion is then very little more than four-fifths of the common air employed. We may conclude that…almost all the inflammable air and about one fifth of the common air…are condensed into the dew which lines the glass.”

"It appears from these experiments, that this air, like other inflammable substances, cannot burn without the assistance of common air."

Henry Cavendish

Defining water

Although Cavendish used the term “phlogisticate”, he managed to demonstrate that the only new material produced was water, and deduced that two volumes of inflammable air had combined with one volume of oxygen. In other words, he showed that the composition of water is H2O. Although he reported his findings to Joseph Priestley, Cavendish was so diffident about publishing the results that his friend the Scottish engineer James Watt was the first to announce the formula, in 1783.

Among his many contributions to science, Cavendish went on to calculate the composition of air as “one part dephlogisticated air [oxygen], mixed with four of phlogisticated [nitrogen]” – the two gases we now know make up 99 per cent of Earth’s atmosphere.

The first hydrogen balloon, inspired by Cavendish, was cheered by a huge crowd of spectators. As hydrogen is so explosive, modern balloons use helium.

HENRY CAVENDISH

One of the strangest and most brilliant pioneers of 18th century chemistry and physics, Henry Cavendish was born in 1731 in Nice, France. His grandfathers were both dukes, and he was immensely rich. After his studies at the University of Cambridge, he lived and worked alone in his house in London. A man of few words and shy of women, it was said that he ordered his meals by leaving notes for his servants.

Cavendish attended meetings of the Royal Society for about 40 years, and also assisted Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution. He did significant original research into chemistry and electricity, accurately described the nature of heat, and measured Earth’s density – or, as people said, “weighed the world”. He died in 1810. In 1874, the University of Cambridge named its new physics laboratory in his honour.

Key works

1766 Three Papers Containing Experiments on Factitious Air

1784 Experiments on Air (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London)

See also: Empedocles • Robert Boyle • Joseph Black • Joseph Priestley • Antoine Lavoisier • Humphry Davy