IN CONTEXT

Physics

1643 Evangelista Torricelli invents the barometer using a tube of mercury.

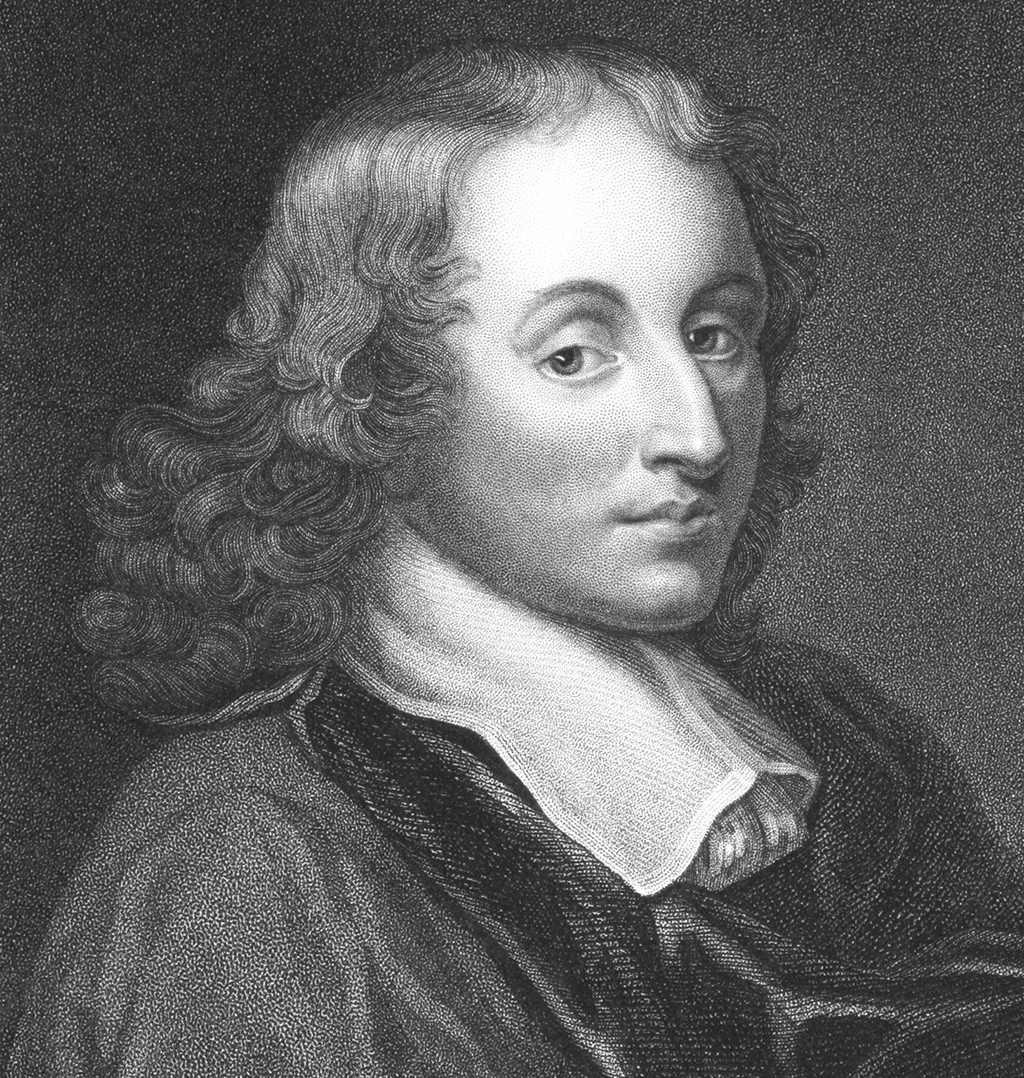

1648 Blaise Pascal and his brother-in-law demonstrate that air pressure decreases with altitude.

1650 Otto von Guericke carries out experiments on air and vacuums, first published in 1657.

1738 Swiss physicist Daniel Bernoulli publishes Hydrodynamica, describing a kinetic theory of gases.

1827 Scottish botanist Robert Brown explains the motion of pollen in water as a result of collisions with water molecules moving in random directions.

In the 17th century, several scientists across Europe investigated the properties of air, and their work was to lead Anglo-Irish scientist Robert Boyle to produce his mathematical laws describing pressure in a gas. This work was tied in to a wider debate about the nature of the space between stars and planets. The “atomists” held that there was empty space between celestial bodies, whereas the Cartesians (followers of the French philosopher René Descartes) held that the space between particles was filled with an unknown substance called the aether, and that it was impossible to produce a vacuum.

"We live submerged at the bottom of an ocean of the element air, that by unquestioned experiments is known to have weight."

Evangelista Torricelli

Barometers

In Italy, the mathematician Gasparo Berti carried out experiments designed to work out why a suction pump could not raise water more than 10m (33ft) high. Berti took a long tube, sealed it at one end and filled it with water. He then inverted the tube with its mouth in a tub of water. The level of water in the tube fell until the column was about 10m (30ft) high. In 1642, fellow Italian Evangelista Torricelli, hearing of Berti’s work, constructed a similar apparatus but used mercury instead of water. Mercury is more than 13 times denser than water, so his column of liquid was only about 76cm (30in) high. Torricelli’s explanation for this was that the weight of the air above the mercury in the dish was pressing down on it, and that this balanced the weight of the mercury inside the column. He said that the space in the tube above the mercury was a vacuum. This is explained today in terms of pressure (force on a certain area), but the basic idea is the same. Torricelli had invented the first mercury barometer.

French scientist Blaise Pascal heard of Torricelli’s barometer in 1646, prompting him to start some experiments of his own. One of these, carried out by his brother-in-law Florin Périer, was to demonstrate that air pressure changed depending on altitude. One barometer was set up in the grounds of a monastery in Clermont, and observed by a monk during the day. Périer carried the other to the top of Puy de Dôme, about 1,000m (3,200ft) above the town. The column of mercury was more than 8cm (3in) shorter at the top of the mountain than in the monastery garden. As there is less air above a mountain than there is above the valley below it, this showed that it was indeed the weight of the air that held the liquid in the tubes of mercury or water. For this, and other work, the modern unit of pressure is named after Pascal.

The barometer invented by Evangelista Torricelli used a column of mercury to measure air pressure. Torricelli correctly reasoned that it was the air pressing down on the mercury in the cistern that balanced the column of mercury in the tube.

Blaise Pascal’s experiments with barometers showed how air pressure varied with altitude. In addition to physics, Pascal also made significant contributions to mathematics.

Air pumps

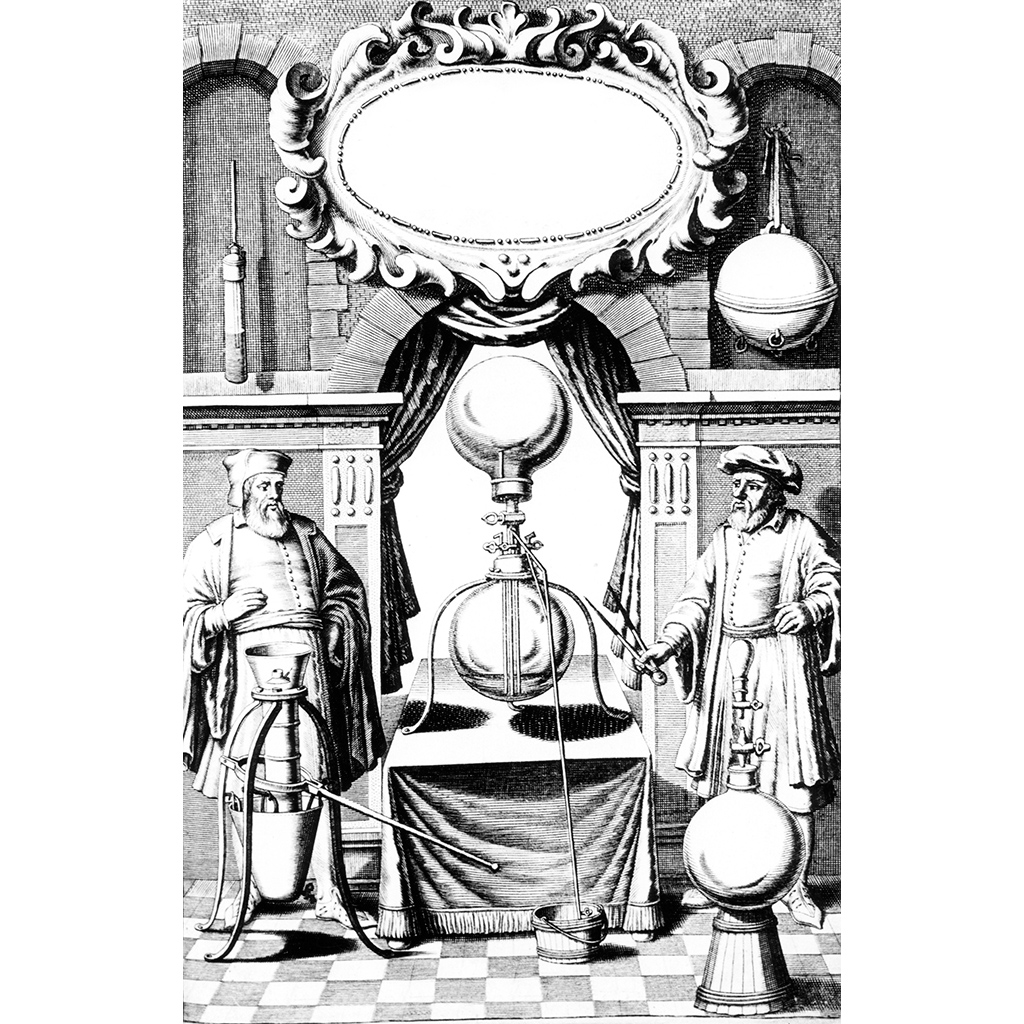

The next important breakthrough was made by Prussian scientist Otto von Guericke, who made a pump that was capable of pumping some of the air out of a container. He carried out his most famous demonstration in 1654, when he put two metal hemispheres together with an airtight seal between them and pumped the air out of them –two teams of horses were unable to pull the hemispheres apart. Before the air was pumped out, the air pressure inside the sealed hemispheres was the same as the air pressure outside. Without the air inside, pressure from the outside air held the hemispheres together.

Robert Boyle learned of von Guericke’s experiments when they were published in 1657. To carry out experiments of his own, Boyle commissioned Robert Hooke to design and build an air pump. Hooke’s air pump consisted of a glass “receiver” (container) whose diameter was nearly 40cm (16in), a cylinder with a piston below it, and an arrangement of plugs and stopcocks between them. Successive movements of the piston drew more and more air out of the receiver. Owing to slow leaks in the seals of the equipment, the near-vacuum inside the receiver could only be maintained for a short time. Nevertheless, the machine was a great improvement on anything made previously, an example of the importance of technology to the furthering of scientific investigation.

"Men are so accustomed to judge of things by their senses that, because the air is indivisible, they ascribe but little to it, and think it but one remove from nothing."

Robert Boyle

Experimental results

Boyle carried out a number of different experiments with the air pump, which he described in his 1660 book New Experiments Physico-Mechanical. In the book, he is at pains to point out that the results described are all from experiment, as at the time even such noted experimentalists as Galileo often also reported the results of “thought experiments”.

Many of Boyle’s experiments were directly connected to air pressure. The receiver could be modified to hold a Torricelli barometer, with the tube sticking out of the top of the receiver and sealed in place with cement. As the pressure in the receiver was reduced, the level of the mercury fell. He also carried out the opposite experiment, and found that raising the pressure inside the receiver made the level of the mercury rise. This confirmed the previous findings of Torricelli and Pascal.

Boyle noted that it became harder and harder to pump air out of the receiver as the amount of air left decreased, and also showed that a half-inflated bladder in the receiver increased in volume as the air surrounding it was removed. A similar effect on the bladder could be achieved by holding it in front of a fire. He gave two possible explanations for the “spring” of the air that caused these effects: each particle of the air was compressible like a spring and the whole mass of air resembled a woollen fleece, or the air consisted of particles moving randomly.

This was similar to the view of the Cartesians, although Boyle did not agree with the idea of the aether, but suggested that the “corpuscles” were moving in empty space. His explanation is remarkably similar to the modern kinetic theory, which describes the properties of matter in terms of moving particles.

Some of Boyle’s experiments were physiological, investigating the effects on birds and mice of reducing the pressure of the air, and speculating on how air is moved in and out of lungs.

Otto von Guericke built the first air pump. His experiments with the pump provided evidence against Aristotle’s idea that “Nature abhors a vacuum”.

"If the height of the mercury column is less on the top of a mountain than at the foot of it, it follows that the weight of the air must be the sole cause of the phenomenon."

Blaise Pascal

Boyle’s Law

Boyle’s Law states that the pressure of a gas multiplied by its volume is a constant, as long as the amount of gas and the temperature are kept the same. In other words, if you decrease the volume of a gas, its pressure increases. It is this increased pressure that produces the spring of the air. You can feel this effect using a bicycle pump by covering the end with a finger and pushing the handle in.

Although it bears his name, this law was first proposed not by Boyle, but by English scientists Richard Towneley and Henry Power, who carried out a series of experiments with a Torricelli barometer and published their results in 1663. Boyle saw an early draft of the book and discussed the results with Towneley. He confirmed them by experiment and published “Mr Towneley’s hypothesis” in 1662 as part of a response to criticism of his original experiments.

Boyle’s work on gases was particularly significant because of his careful experimental technique, and also his full reporting of all his experiments and their possible sources of error, whether or not they gave the expected results. This led many to seek to extend his work. Today, Boyle’s Law has been combined with laws worked out by other scientists to form the “Ideal Gas Law”, which approximates to the behaviour of real gases under changes of temperature, pressure, or volume. His ideas would also eventually lead to the development of the kinetic theory.

ROBERT BOYLE

Robert Boyle was born in Ireland, the 14th child of the Earl of Cork. He was tutored at home before attending Eton College in England and then touring Europe. His father died in 1643, leaving him enough money to indulge his interest in science full time. Boyle moved back to Ireland for a couple of years, but lived in Oxford from 1654 to 1668 so that he could carry out his work more easily, and then moved to London.

Boyle was part of a group of men studying scientific subjects called the “Invisible College”, who met in London and Oxford to discuss their ideas. This group became the Royal Society in 1663, and Boyle was one of the first council members. In addition to his interests in science, Boyle carried out experiments in alchemy and wrote about theology and the origin of different human races.

Key works

1660 New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects

1661 The Sceptical Chymist

See also: Isaac Newton • John Dalton • Robert FitzRoy