IN CONTEXT

Meteorology

1643 Evangelista Torricelli invents the barometer, which measures air pressure.

1805 Francis Beaufort develops the Beaufort scale of wind force.

1847 Joseph Henry proposes a telegraph link to warn the eastern United States of storms coming from the west.

1870 The US Army Signal Corps begins creating weather maps for the whole USA.

1917 The Bergen School of Meteorology in Norway develops the notion of weather fronts.

2001 Systems of Unified Surface Analysis use powerful computers to give highly detailed local weather.

Acentury and a half ago, notions of weather prediction were deemed little more than folklore. The man who changed that and gave us modern weather forecasting was British naval officer and scientist Captain Robert FitzRoy.

FitzRoy is better known today as the captain of the Beagle, the ship that carried Charles Darwin on the voyage that led to his theory of evolution by natural selection. Yet FitzRoy was a remarkable scientist in his own right.

FitzRoy was just 26 when he sailed from England with Darwin in 1831. Yet he had already served more than a decade at sea, and had studied at the Royal Naval College at Greenwich, where he was the first candidate to pass the lieutenant’s exam with perfect marks. He had even commanded the Beagle on an earlier survey trip around South America, where the importance of studying the weather was impressed upon him. His ship had almost come to grief in a violent wind off the coast of Patagonia after he had ignored the warning signs of falling pressure on the ship’s barometer.

"With a barometer, two or three thermometers, some brief instructions, and an attentive observation, not of instruments only, but the sky and atmosphere, one may utilise Meteorology."

Robert FitzRoy

Naval weather pioneers

It was no coincidence that many of the first breakthroughs in weather forecasting came from naval officers. Knowing what weather lay ahead was crucial in the days of sailing ships. Missing a good wind could have huge financial consequences – and being caught at sea in a storm could be disastrous.

Two naval officers in particular had already made significant contributions. One was Irish mariner Francis Beaufort, who created a standard scale showing the wind speed or “force” linked to particular conditions at sea, and later on land. This allowed the severity of storms to be recorded and compared methodically for the first time. The scale ranged from 1, indicating “light air” to 12, “hurricane”. The first time the Beaufort scale was used was by FitzRoy on the Beagle voyage. Thereafter it became standard in all naval ships’ logs.

Another naval weather pioneer was American Matthew Maury. He created wind and current charts for the North Atlantic, which resulted in dramatic improvements for sailing times and certainty. He also advocated the creation of an international sea and land weather service, and led a conference in Brussels in 1853 that began to coordinate observations on conditions at sea from all around the world.

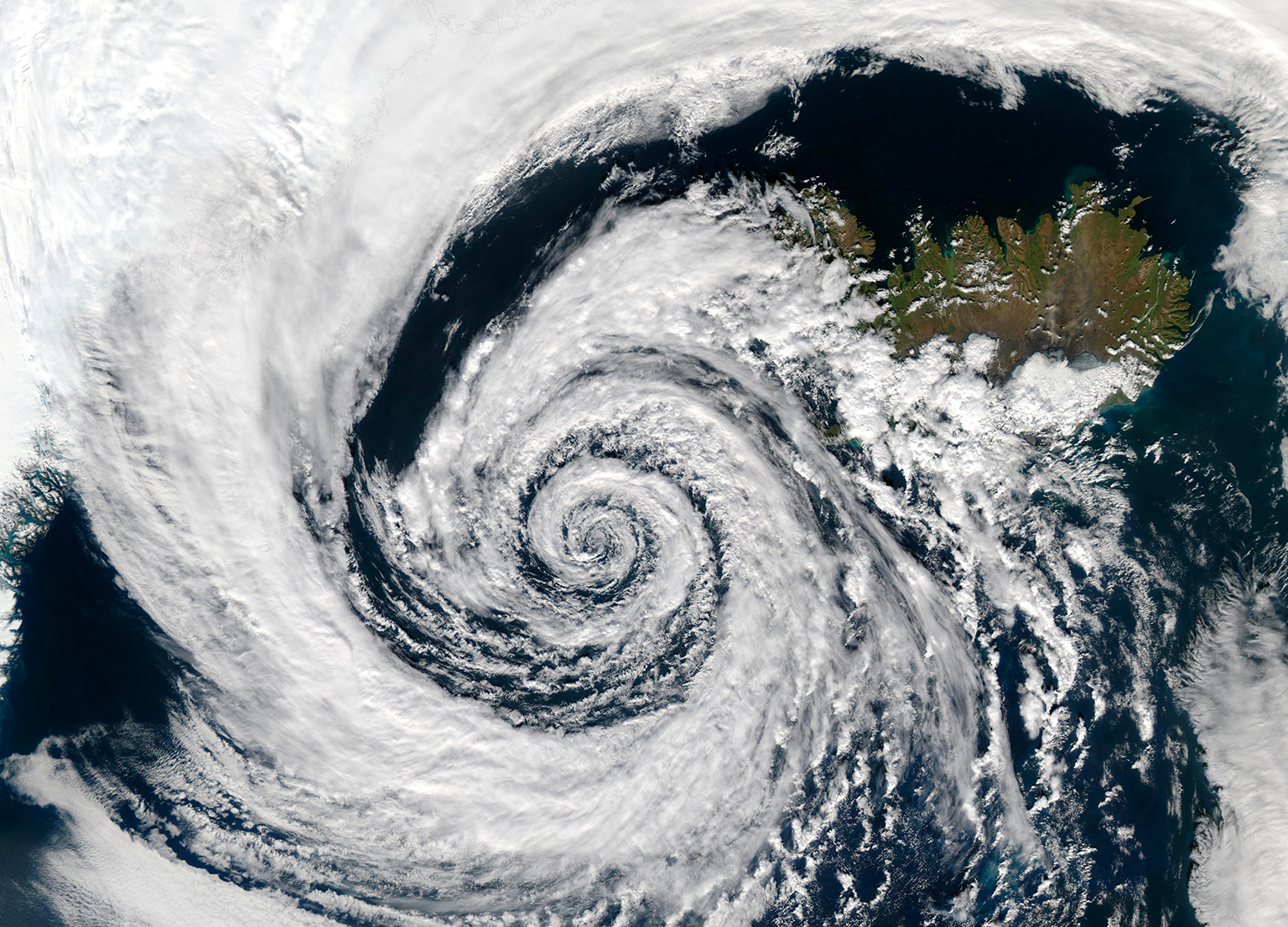

Before FitzRoy began his weather reporting systems, mariners had already observed that winds form cyclonic patterns in hurricanes, and that wind direction could be used to predict the storm’s path.

The Meteorogical Office

In 1854, FitzRoy, encouraged by Beaufort, was given the task of setting up the British contribution at the Meteorological Office. But with characteristic zeal and insight, FitzRoy went much further than his brief. He began to see that a system of simultaneous weather observations from around the world could not only reveal hitherto undiscovered patterns, but actually be used to make weather predictions.

Observers already knew that in tropical hurricanes, for instance, the winds blow in a circular or “cyclonic” pattern around a central area of low air pressure or “depression”. It was soon realized that most of the large storms that blow in the mid-latitudes show this cyclonic depression shape. So the direction of the wind gives a clue as to whether the storm is approaching or receding.

In the 1850s, better records of weather events, and the use of the new electric telegraph to communicate over long distances, almost instantly revealed that cyclonic storms, which form over land, move eastwards. In contrast, hurricanes (tropical North Atlantic storms) form over water and migrate westwards. So in North America when a storm hit one place far inland, a telegraph could be sent to warn places further east that a storm was on its way. Observers already knew that a drop in air pressure on the barometer gave warning of a storm to come. The telegraph allowed such readings to be relayed rapidly over great distances and therefore gave warnings much further in advance.

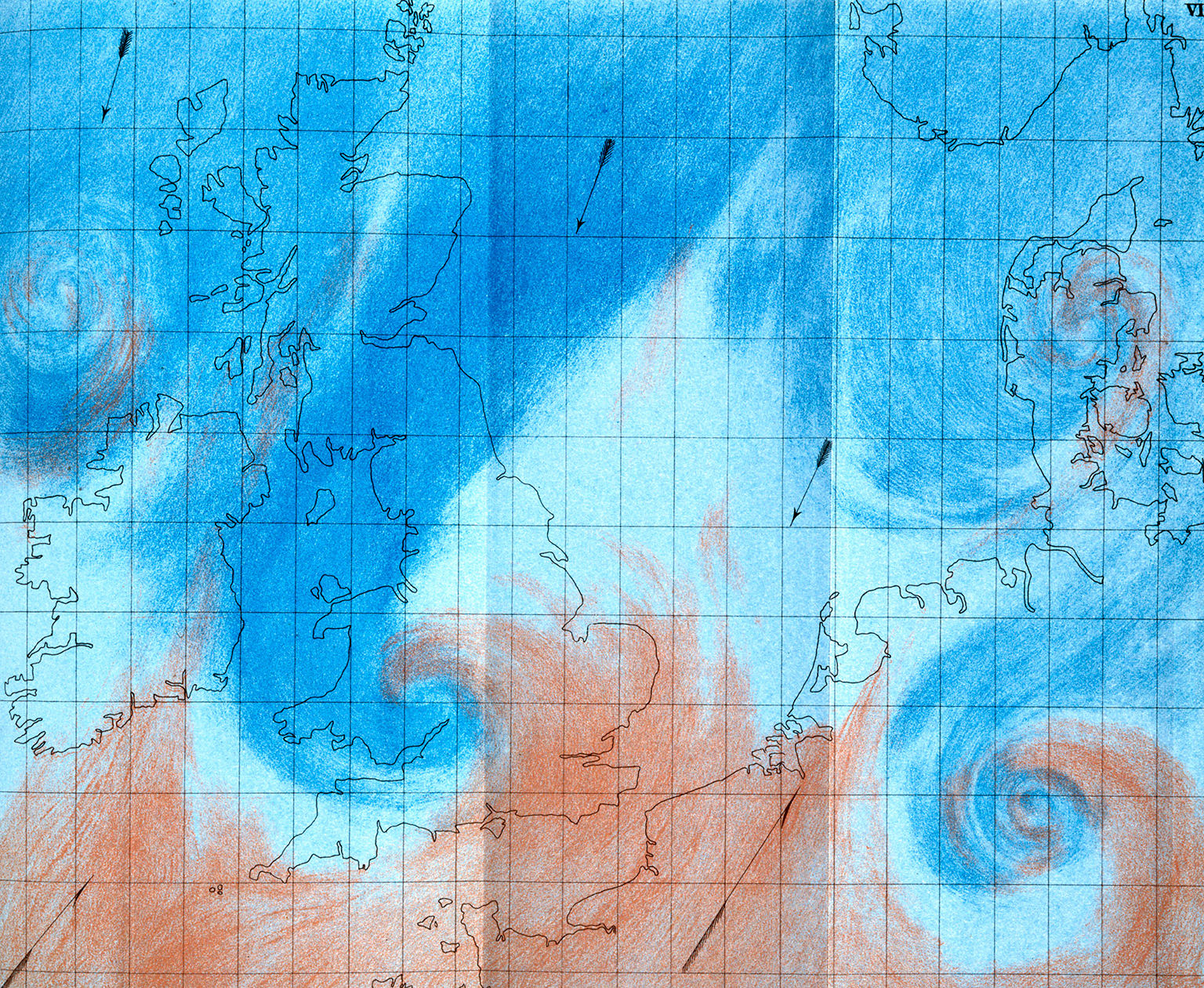

FitzRoy coloured his daily “synoptic” charts in crayon. This one, made in 1863, shows a low-pressure front bringing storms towards northern Europe from the west. The lower right of the chart reveals a cyclone forming.

Synoptic weather

FitzRoy understood that the keys to weather prediction were systematic observations of air pressure, temperature, and wind speed and direction taken at set times from widely spread locations. When these observations were sent instantly by telegraph to his coordinating office in London, he could build up a picture or “synopsis” of weather conditions over a vast area.

This synopsis gave such a complete picture of the weather conditions that it not only revealed current weather patterns on a wide scale, it also enabled weather patterns to be tracked. FitzRoy realized that weather patterns were repeated. From this, it was clear to him that he could work out how weather patterns may develop over a short time in the future, from how they have developed in the past. This provides the basis for a detailed forecast of the weather at any and every point within the region covered. This was a remarkable insight that formed the basis of modern forecasting.

The observation figures alone were enough, but FitzRoy also used them to create the first modern meteorological chart, the “synoptic” chart that revealed the swirling shapes of cyclonic storms as clearly as satellite pictures do today. FitzRoy’s ideas were summed up in his book, entitled simply The Weather Book (1863), which introduced the word “forecast” and laid out the principles of modern forecasting for the first time.

A crucial step was to divide the British Isles into weather areas, collate current weather conditions, and use past weather data from each area to help make forecasts. FitzRoy recruited a network of observers, particularly at sea and in ports in the British Isles. He also obtained data from France and Spain, where the idea of constant weather observation was catching on. Within a few years, his network was operating so effectively that he could get a daily snapshot of weather patterns right across Western Europe. Patterns in the weather were revealed so clearly that he could forecast how it was likely to change over the next day at least – and so produce the first national forecasts.

"I try, by my warnings of probable bad weather, to avoid the need for a life-boat."

Robert FitzRoy

Daily weather forecasts

Every morning, weather reports would come to FitzRoy’s office from scores of weather stations across Western Europe, and within an hour, the synoptic picture was worked out. Instantly, forecasts were despatched to The Times newspaper to be published for all to read. The first weather forecast was published by the newspaper on 1 August 1861.

FitzRoy set up a system of signalling cones in highly visible places at ports to warn if a storm was on the way and from which direction. This system worked so well that it saved countless lives.

Some shipowners, however, resented the system when their captains began to delay setting sail if warned of a storm. There were also problems disseminating the forecasts in time. It took 24 hours to distribute the newspaper, so FitzRoy had to make forecasts for not just one day ahead but two – otherwise the weather would have happened by the time people read his forecasts. He was aware that longer-range forecasts were far more unreliable, and was frequently exposed to ridicule, particularly when The Times disassociated itself from mistakes.

FitzRoy’s legacy

Faced with a barrage of ridicule and criticism from vested interests, the forecasts were suspended and FitzRoy committed suicide in 1865. When it was discovered that he had spent his fortune on his research at the Meteorological Office, the government compensated his family. But within a few years, pressure from mariners ensured that his storm warning system was again in widespread use. Picking up the detailed forecasts and storm warnings for particular shipping areas is now an essential part of every mariner’s day.

As communications technology improved and added ever more detail to the observational data, the value of FitzRoy’s system came into its own in the 20th century.

Modern forecasting

Today, the world is dotted with a network of more than 11,000 weather stations, in addition to the numerous satellites, aircraft, and ships – all continuously feeding information into a global meteorological data bank. Powerful number-crunching supercomputers churn out weather forecasts that are, in the short-term at least, highly accurate, and a huge range of activities, from air travel to sporting events, rely on them.

This weather station, located in the remote mountains of Ukraine, sends data on temperature, humidity, and wind speed via satellite to weather supercomputers.

"Having collated and duly considered the Irish telegrams [or from any other weather area], the first forecast for that district is drawn…and forthwith sent out for immediate publication."

Robert FitzRoy

ROBERT FITZROY

Born in 1805 in Suffolk, England, to an aristocratic family, Robert FitzRoy joined the Navy aged just 12. He went on to serve many years at sea as an outstanding sea captain. He captained the Beagle on two major survey voyages to South America, including the round-the-world voyage with Charles Darwin. FitzRoy was, however, a devout Christian who opposed Darwin’s theory of evolution. After leaving active service in the Navy, FitzRoy became governor of New Zealand, where his even-handed treatment of the Maori earned him the resentment of the settlers. He returned to England in 1848 to command the Navy’s first screw-driven ship, and was appointed head of the British Meteorological Office when it was established in 1854. There he developed the methods that became the foundation of scientific weather forecasting.

Key works

1839 Narrative of the Voyages of the Beagle

1860 The Barometer Manual

1863 The Weather Book

See also: Robert Boyle • George Hadley • Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis • Charles Darwin