IN CONTEXT

Chemistry

1754 Joseph Black isolates the first gas, carbon dioxide.

1766 Henry Cavendish prepares hydrogen.

1772 Carl Scheele isolates a third gas, oxygen, two years before Priestley, but does not publish his findings until 1777.

1774 In Paris, Priestley demonstrates his method to Antoine Lavoisier, who makes the new gas and publishes his results in May 1775.

1779 Lavoisier gives the gas the name “oxygène”.

1783 Geneva’s Schweppes Company starts making the soda water Priestley invented.

1877 Swiss chemist Raoul Pictet produces liquid oxygen, which will be used in rocket fuel, industry, and medicine.

Following Joseph Black’s pioneering discovery of “fixed air”, or carbon dioxide (CO2), an English clergyman named Joseph Priestley became interested in investigating various other “airs”, or gases, and identified several more – most notably oxygen.

While a minister in Leeds, Priestley visited the brewery close to his lodgings. The layer of air above the brewing vat was already known to be fixed air. He found that when he lowered a candle over the vat, the candle went out about 30cm (12in) above the froth, where the flame entered the layer of fixed air floating there. The smoke drifted across the top of the fixed air, making it visible and revealing the boundary between the two airs. He also noticed that the fixed air flowed over the side of the vat and sank to the floor, because it was denser than “ordinary” air. When Priestley experimented with dissolving fixed air in cold water, sloshing it from one vessel to another, he found that it made a refreshing sparkling drink, which later led to the craze for soda water.

Releasing oxygen

On 1 August 1774, Priestley first isolated his new gas – which we now know as oxygen (O2) – from mercuric oxide in a sealed glass flask by heating it with sunlight and a magnifying glass. He later discovered that this new gas kept mice alive for much longer than ordinary air, was pleasant to breathe and more energizing than ordinary air, and supported the combustion of various substances he burned as fuel. He also showed that plants produce the gas in sunlight – a first hint of the process we call photosynthesis. At the time, however, combustion was thought to involve the release from a fuel of a mysterious material called phlogiston. Because this new gas did not burn, and therefore must contain no phlogiston, he called it “dephlogisticated air”.

Priestley isolated several other gases at about this time, but then went on a European tour, and did not publish his results until late the following year. Swedish chemist Carl Scheele had prepared oxygen two years before Priestley, but did not publish his results until 1777. Meanwhile in Paris, Antoine Lavoisier heard of Scheele’s work, was given a demonstration by Priestley, and promptly made his own oxygen. His experiments on combustion and respiration proved that combustion is a process of combining with oxygen, not liberating phlogiston. In respiration, oxygen absorbed from the air reacts with glucose and releases carbon dioxide, water, and energy. He named the new gas oxygène, or “acid-maker”, when he discovered that it reacts with some materials – such as sulphur, phosphorus, and nitrogen – to make acids.

This led many scientists to abandon phlogiston, but Priestley, though a great experimenter, clung to the old theory to explain his discoveries and made little further contribution to chemistry.

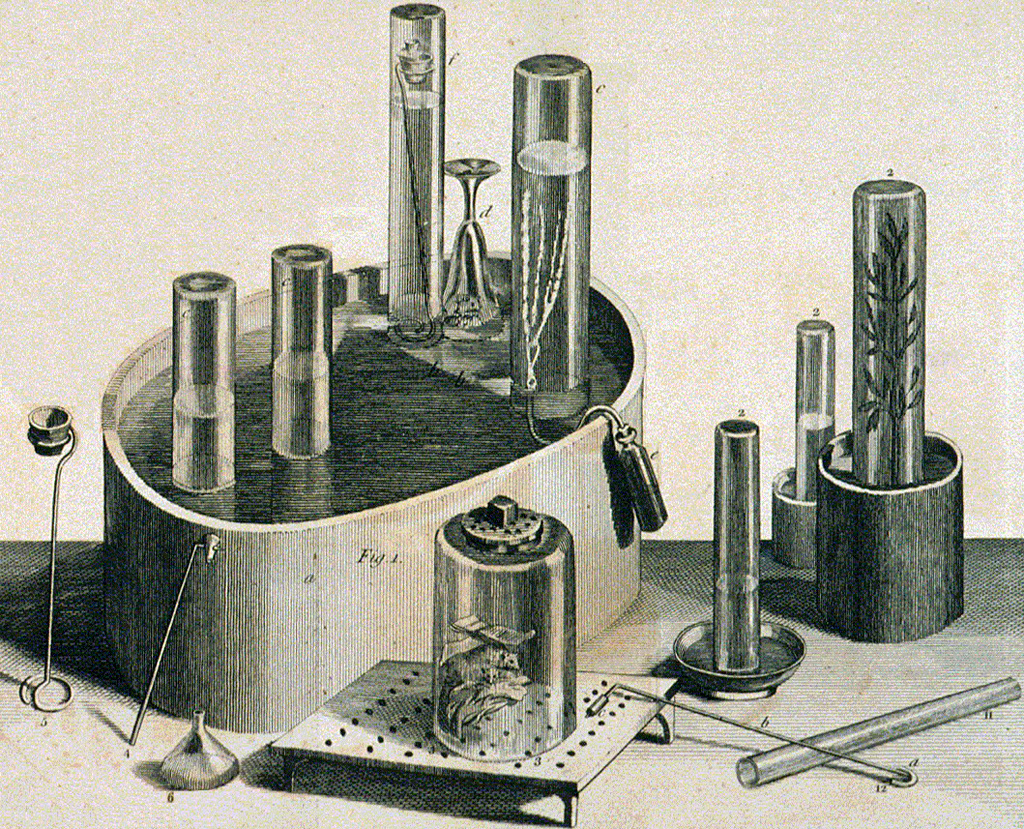

Priestley’s apparatus for his gas experiments appear in his book about his discoveries. At the front, a mouse is kept in oxygen under a jar; on the right, a plant releases oxygen in a tube.

"The most remarkable of all the kinds of air I have produced…is, one that is five or six times better than common air, for the purpose of respiration."

Joseph Priestley

JOSEPH PRIESTLEY

Born on a farm in Yorkshire, Joseph Priestley was brought up as a dissenting Christian, and was intensely religious and political all his life.

Priestley became interested in gases while living in Leeds in the early 1770s, but his best work was done after he moved to Wiltshire as librarian to the Earl of Shelburne. His duties were light and left him time to carry out research. He later fell out with the earl – his political views may have been too radical – and in 1780, he moved to Birmingham. Here he joined the Lunar Society, an informal but influential group of free-thinkers, engineers, and industrialists.

Priestley’s support for the French Revolution made him unpopular. In 1791, his house and laboratory were burned down, forcing him to move to London and then to America. He settled in Pennsylvania, and died there in 1804.

Key works

1767 The History and Present State of Electricity

1774–77 Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

See also: Joseph Black • Henry Cavendish • Antoine Lavoisier • John Dalton • Humphry Davy