IN CONTEXT

Earth science

1824 Norwegian Jens Esmark suggests that glaciers are responsible for the creation of fjords, erratics, and moraines.

1830 Charles Lyell argues that the laws of nature have always been the same, so the clues to the past lie in the present.

1835 Swiss geologist Jean de Charpentier argues that erratics near Lake Geneva were transported by ice from the Mont Blanc area in an “Alpine glaciation”.

1875 Scottish scientist James Croll argues that variations in Earth’s orbit could explain the temperature changes that cause an ice age.

1938 Serbian physicist Milutin Milankovic relates changes in climate to periodic changes in Earth’s orbit.

When glaciers sweep across a landscape, they leave signature features behind them. Glaciers can scour rocks flat or leave them smoothly rounded, often with striations (scratch marks) showing the direction in which the ice moved. They also leave behind erratics – boulders that have been carried long distances by the ice. These can usually be identified because their composition is different from the rocks on which they lie. Many erratics are too large to have been moved by rivers, which is the usual way that rocks are carried across a landscape. A rock of a different kind from rocks around it, therefore, is a tell-tale sign that a glacier once passed by. Another is the presence of moraines in valleys. These are piles of boulders that were pushed aside when the glacier was growing, and left behind when it retreated.

Riddle of the rocks

Geologists in the 19th century recognized such features as striations, erratics, and moraines as evidence of glaciers. What they could not explain was why such features were found in areas on Earth that had no glaciers. One theory argued that rocks were moved by repeated flooding. Floods could explain the “boulder drift” (the sands, clays, and gravels that included erratic boulders) that overlay much of the bedrock of Europe. The material might have been deposited when the last flood retreated. The largest erratics could have been caught up in icebergs, which deposited the rocks when they melted. But the theory could not explain all of the features.

The ice age revealed

During the 1830s, Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz spent several holidays in the European Alps studying glaciers and their valleys. He realized that glacial features everywhere, not just in the Alps, could be explained if Earth had once been covered in far more ice than at present. The glaciers of today must be the remnants of ice sheets that had at one time covered most of the globe. But before he published his theory Agassiz wanted to convince others. He had met William Buckland, a prominent English geologist, while excavating fossil fishes in the Old Red Sandstone rocks in the Alps. When Agassiz showed him the evidence for his theory of an ice age, Buckland was convinced, and in 1840 the two men toured Scotland to look for evidence of glaciation there. After the tour, Agassiz presented his ideas to the Geological Society of London. Although he had convinced Buckland and Charles Lyell – two of the leading geologists of the day – the other members of the society were unimpressed. A near-global glaciation seemed no more probable than a global flood. However, the idea of ice ages gradually gained acceptance, and today there is evidence from many different fields of geology that ice has covered much of Earth’s surface many times in the past.

Agassiz was the first to suggest that large erratics, such as these in the Caher Valley of Ireland, were deposited by ancient glaciers.

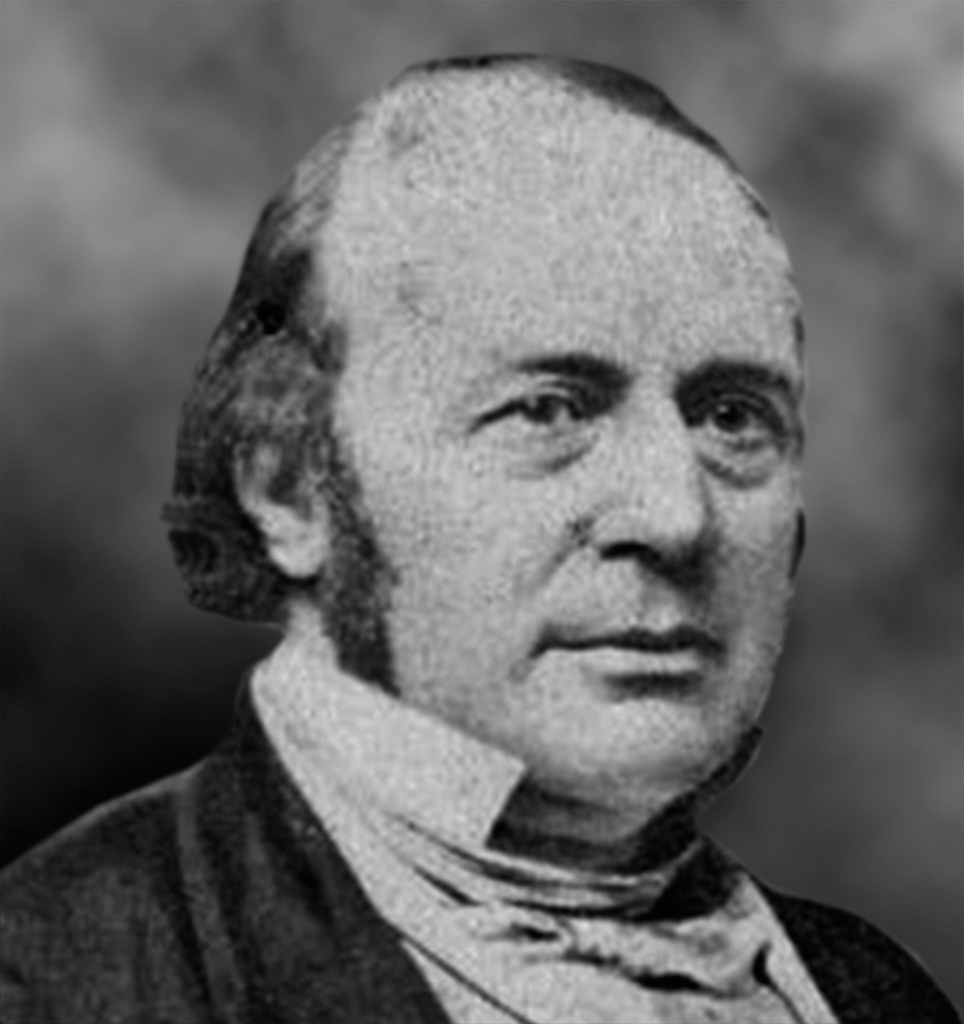

LOUIS AGASSIZ

Born in a small Swiss village in 1807, Louis Agassiz studied to be a physician, but became a professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. His first scientific work, under the French naturalist Georges Cuvier, involved classifying freshwater fish from Brazil, and Agassiz went on to undertake extensive work on fossilized fish. In the late 1830s, his interests spread to glaciers and zoological classification. In 1847, he took a post at Harvard University in the USA.

Agassiz never accepted Darwin’s theory of evolution, believing that species were “ideas in the mind of God” and that all species had been created for the regions they inhabited. He advocated “polygenism”, a belief that different human races did not share a common ancestor, but were created separately by God. In recent years, his reputation has been tarnished by his apparent advocacy of racist ideas.

Key works

1840 Study on Glaciers

1842–46 Nomenclator Zoologicus

See also: William Smith • Alfred Wegener