IN CONTEXT

Earth science

1858 Antonio Snider-Pellegrini makes a map of the Americas joined to Europe and Africa, to account for identical fossils found on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

1872 French geographer Élisée Reclus proposes that motion of the continents caused the formation of the oceans and mountain ranges.

1885 Eduard Suess suggests the southern continents were once joined by land bridges.

1944 British geographer Arthur Holmes proposes convection currents in Earth’s mantle as the mechanism that moves the crust at the surface.

1960 American geologist Harry Hess proposes that seafloor spreading pushes apart the continents.

In 1912, German meteorologist Alfred Wegener combined several strands of evidence to put forward a theory of continental drift, which suggested that Earth’s continents were once joined but moved apart over millions of years. Scientists only accepted his theory once they had worked out what made such vast landmasses move.

Looking at the first maps of the New World and Africa, Francis Bacon had noted, in 1620, that the eastern coasts of the Americas are roughly parallel with the western coasts of Europe and Africa. This led scientists to speculate that these landmasses were once joined, challenging conventional notions of a solid, unchanging planet.

In 1858, Paris-based geographer Antonio Snider-Pellegrini showed that similar plant fossils had been found on either side of the Atlantic, dating back to the Carboniferous period, 359–299 million years ago. He made maps showing how the American and African continents may once have fitted together, and attributed their separation to the biblical Flood. When fossils of Glossopteris ferns were found in South America, India, and Africa, Austrian geologist Eduard Suess argued that they must have evolved on a single landmass. He suggested that the southern continents were once linked by land bridges across the sea, forming a supercontinent that he called Gondwanaland.

Wegener found more examples of similar organisms separated by oceans, but also similar mountain ranges and glacial deposits. Instead of earlier ideas that portions of a supercontinent had sunk beneath the waves, he thought perhaps it had split apart. Between 1912 and 1929, he expanded on this theory. His supercontinent – Pangaea – joined Suess’s Gondwanaland to the northern continents of North America and Eurasia. Wegener dated the fragmentation of this single landmass to the end of the Mesozoic era, 150 million years ago, and pointed to Africa’s Great Rift Valley as evidence of ongoing continental breakup.

Search for a mechanism

Wegener’s theory was criticized by geophysicists for not explaining how continents move. In the 1950s, however, new geophysical techniques revealed a wealth of new data. Studies of Earth’s past magnetic field indicated that the ancient continents lay in a different position relative to the poles. Sonar mapping of the sea bed revealed signs of more recent ocean-floor formation. This was found to occur at mid-ocean ridges, as molten rock erupts through cracks in Earth’s crust and spreads away from the ridges as new rock erupts.

In 1960, Harry Hess realized that seafloor spreading provided the mechanism for continental drift, and presented his theory of plate tectonics. Earth’s crust is made up of giant plates that continually shift as convection currents in the mantle below bring new rock to the surface, and it is the formation and destruction of ocean crust that leads to the displacement of continents. This theory not only vindicated Wegener but is now the bedrock of modern geology.

Wegener’s supercontinent is just one in a long series. Geologists think the continents may be converging again, to form another supercontinent 250 million years from now.

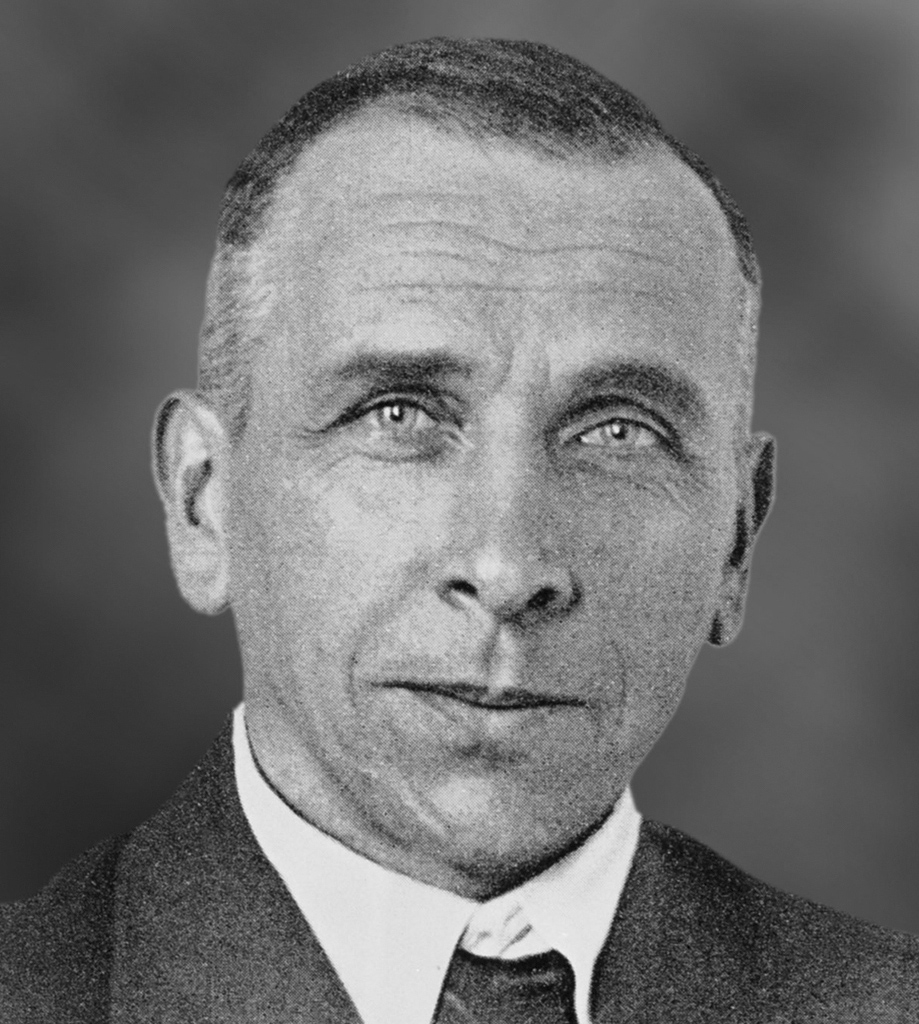

ALFRED WEGENER

Born in Berlin, Alfred Lothar Wegener obtained a doctorate in astronomy from the University of Berlin in 1904, but soon became more interested in earth science. Between 1906 and 1930, he made four journeys to Greenland as part of his pioneering meteorological studies of Arctic air masses. He used weather balloons to track air circulation and took samples from deep within the ice for evidence of past climates.

In between these expeditions, Wegener developed his theory of continental drift in 1912, and published it in a book in 1915. He produced revised and expanded editions in 1920, 1922, and 1929, but was frustrated by the lack of recognition for his work.

In 1930, Wegener led a fourth expedition to Greenland, hoping to collect evidence in support of the drift theory. On 1 November, his 50th birthday, he set out across the ice to fetch badly needed supplies, but he died before reaching the main camp.

Key work

1915 The Origin of Continents and Oceans

See also: Francis Bacon • Nicholas Steno • James Hutton • Louis Agassiz • Charles Darwin