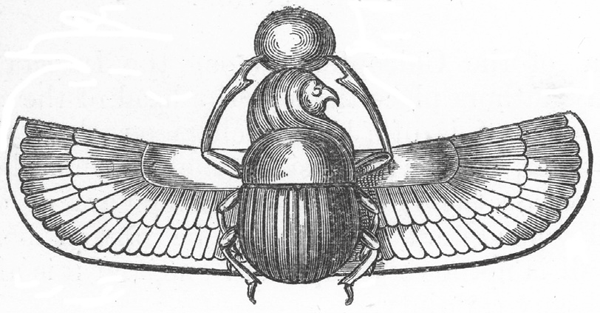

Fig. 29 Some ancient Egyptian scarab representations were more fanciful than others, but their sheer numbers and diversity speak of the reverence directed at dung beetles.

A CLOSER LOOK – WHO LIVES IN DUNG?

THE ANCIENTS KNEW, only too well, who lived in dung. And they celebrated these creatures with idolatrous zeal. Obviously, my favourite exhibit at the British Museum is the 1.5 m long, 1 m high, giant stone sculpture of a sacred scarab. It is beautiful. It was created around 332–330 BC, during the Egyptian Ptolemaic period. This was something like 1,800–2,300 years after scarabs were truly held sacred, and was made during a period of sentimental nostalgia for the good old days. Although, perhaps, a pastiche, it’s an awe-inspiring piece of art – figurative yet symbolic, mundane yet iconic. It draws from a familiarity with the natural world of excrement that might surprise today’s prudish, urban, urbane, reader. At the height of scarabmania, during the Early Middle Kingdom, around 2000 BC, scarab amulets, necklaces and brooches were by far the most popular items of domestic jewellery; many thousands of them have been unearthed in archaeological digs and there was a Mediterranean-wide industry in manufacturing them, from Sardinia to the Levant.

Though they represent the same type of creature, these models are not all the same. It seems clear that various artisans, in different localities, throughout the centuries, have used a variety of prototypes on which to base their works. Such is the number of well-preserved scarab artefacts that one entomologist (Klausnitzer 1981) has tried to identify which genera might be represented: Scarabaeus, Catharsius, Gymnopleurus, Copris and Hypselogenia, he suggests, and his side-by-side comparisons of beetle outlines and carved effigies are pretty plausible. I don’t think there is any suggestion that ancient scarab carvers knew much about dung beetle classification, or even that there might have been different species, but the fact that we can look at their art, 4,000 years later, and identify the different insects shows, surely, that they had an intimate knowledge of the beetles, that they had seen them, held them in their hands, and examined them carefully enough to reproduce them so accurately in their carvings and quartz ceramic faience modelling.

Fig. 29 Some ancient Egyptian scarab representations were more fanciful than others, but their sheer numbers and diversity speak of the reverence directed at dung beetles.

In this chapter I’d like to suggest that not enough people get to appreciate or handle dung beetles; or dung flies, or the many other dung critters for that matter. Which is a shame. I’ve been fascinated by dung and its denizens since I was a boy. The very first entomological survey I ever wrote up, in my awkward 17-year-old prose, using my best schoolroom handwriting in a large ruled hardback exercise book, and with a scattering of amateurish sketch drawings pasted in, was pompously entitled ‘The South Heighton Aphodius, being an account of those species in the genus Aphodius, in the family Scarabaeidae… etc, etc… found in the parish of South Heighton and parts of Newhaven, Tarring Neville, Beddingham… etc, etc… between 1970 and 1975.’ Just so there was no doubt, I dated it MCMLXXV. I think I was reading too much Victorian literature at the time. It’s tucked away in a corner of my bookshelves now, to remain obscure and unread for a couple of hundred years, when it might be unearthed as a curious historical artefact. My interest in decaying organic matter has stayed with me, and this chapter is, on a more personal note, an exploration of my journey through excreta. Here I’ll be giving details of some of my favourite dung animals, and how to go about finding and observing them. But first a necessary health warning.

Dung is, as first noted in chapter 1, largely made up of bacteria; and these are mostly the kind of bacteria that you don’t want to end up on your food. So, rule number 1: if you’re going to become a scatologist, always wash your hands before eating.

Some years ago I was taken to task after writing what I thought was an amusing article about collecting insects (Jones 1986). In it I related the specialist wet-finger technique for collecting small beetles. This is perfect if you see a tiny beetle running across a hard surface such as a fence post or a log. You simply lick the end of your finger, dab it onto the beetle, lift it up by the adhesion of your spittle on the glossy dome of its wing cases, place a glass collecting tube over the wriggling insect stuck on your finger, and give your hand a smart tap; this dislodges the insect down into the tube. Voilà. I went on to make a joke about how the flavour of one’s finger changes through the day, especially if you have been out dung-beetling. Sadly, my cavalier attitude to personal hygiene was found to be rather tiresome, and someone was obliged to point out that this is just the way to pick up nasty intestinal complaints. Possibly even fatal diseases. They said so in a letter to the editor.

Proper books on dung beetles will insist that disposable rubber gloves should be worn at all times. And this does add something of a formal surgical nature to the dissection of the pat. Many students of dung avoid handling it altogether by using the immersion technique for finding dung beetles – simply put the entire dropping into a large bucket of water. As it disintegrates, the insects within float to the surface, where they can be seen waving their legs about. They can then be hooked out. This doesn’t always work though; Aphodius granarius was always regarded as being very scarce in Finland, which is, as everyone knows, an international centre for dung beetle research. This is because it does not rise to the surface of the water. Manual searching of pats, however, revealed that it is in fact widespread throughout Scandinavia, and frequently found in the UK. The Finns need to abandon their buckets and sharpen their trowels.

You don’t actually need to get down there and in it, to find dung insects. You can observe closely, or at a distance, and watch the comings and goings of endless flies and beetles. Take the advice of a hardened dung-beetler, Eric Matthews, previously of the University of Puerto Rico. He wrote a seminal 18-page paper (Matthews 1963) on the rolling behaviour of the tumblebug, Canthon pilularius, and he clearly states his modus operandi:

The methods used consisted of sitting down and watching the activities of the scarabs.… The author always camped in the immediate area of observation so that he could be present for every phase of activity from beginning to end. Often days were spent in the same spot.… No special techniques were used and no experimentation was attempted.

In other words, he wrote about what he did on his holidays. What a lark, eh? At the other extreme, I am hugely impressed by the energy and verve of another US entomologist, Leland Ossian Howard, whose 1900 paper is a monument to the study of insects associated with human dung (Howard 1900). His was not just a personal exploration of a few sample stools; it was an intense and detailed forensic analysis of large army camp latrines. This was supreme dedication, and his paper is beautifully illustrated with engravings of all the most important flies, and their maggots. For more inspiration, I can thoroughly recommend the excellent general introductions to northern hemisphere temperate dung faunas by Putman (1983), Skidmore (1991) and Floate (2011).

At the gentler end of one’s leisure activities, dung study can be contemplated during a country walk, picnic or safari. You can simply sit and watch the farm animals, or the wildlife, and what they are depositing. If you are lucky enough to be in the vicinity of fresh elephant dung in the spring or summer savannah, you may be inundated by thousands of them. Anywhere south of Bordeaux you might see rollers at work, and be inspired just as were the ancient Egyptians. Just rest easy and watch them go about their business. If you do decide to explore deeper, I recommend a narrow garden trowel, or a stout penknife, but if this is not to hand it is easy enough to tip over the dropping with a stick, to see what is sheltering beneath. So it was when I found myself beside some unusually large spoor (dog I guessed, rather than bear) in a disused Florida orange grove back in 1991. Flicking it over with a dead twig, I uncovered the exquisitely viridescent rainbow scarab, Phanaeus vindex, looking as if it had been shaped from beaten gold and copper, and sporting, in the male, a huge back-curved head horn. Wonderful.

For larger cow and horse droppings, start at the edge, prising apart any natural fissures, and looking into the grass roots under the dung. Small excavations in the dung may show where a diminutive dung beetle is hollowing out a morsel. Sometimes just the tail end and the back legs are visible. A pile of earth beside or under the dung will be the spoil from a tunneller. Unless you are prepared for serious digging, it may be enough to expose the burrow entrance and wait; eventually the beetle may come back up to the surface. Serious entomologists will stick something like a straw into the hole, then dig down until a deeper section of the tunnel is exposed and the process can be repeated. Be warned, this can go on for several metres.

Dung heaps are different from dung, and not a few entomologists insist on the term manure heaps by way of distinguishing them. They have straw, sawdust, hay or whatever other stable, hutch or barn bedding is mixed in with them. Today they are relatively transient piles, easily moved around by JCB and tractor, but in times past they were long-lived, added to, and taken away from, piecemeal, as the farm animals provided and the farmer needed. Over many years they can mature and acquire an important diverse community. They might have fewer strictly dung beetles, but are still rich in decaying organic matter fauna, and they can get quite ripe, in a fermenting, mouldering kind of way. I’m very much a get-stuck-in-there naturalist, but I well remember Earnest Lewis, a coleopterist friend of my father’s, sitting down in smart three-piece suit and tie, and polished leather shoes, to dissect the edge of a manure heap on a short country walk when he came to visit us. He took a small trowel and a plastic sheet and could have gone on to have cocktails with the squire later in the day. I used my bare hands and probably needed a bath before my Mum let me back in the house. So, please, when you’re done, do wash your hands.

THE ENGLISH SCARAB – NOT SO SACRED

We don’t get the roller scarabs, sacred or otherwise, in the UK, and for this I am sad. Our dung fauna is impoverished compared to a mainland Europe only a few miles away over the water, and it is also outperformed by Scandinavia. This is a blunt geohistorical fact, an unfortunate consequence of retreating glaciers after the last ice age and the flooding of Doggerland as it sank between the North Sea and the English Channel, effectively cutting us off from colonists moving north as global temperatures rose 15 millennia ago. Nevertheless there are some real gems amongst the 400 or so dung-associated invertebrates here. And travelling to foreign climes, where the dung is remarkably similar to that in Britain, is a real adventure to be seized with relish.

The nearest we get to a proper scarab in the UK is in the large glossy domed form of Copris lunaris. At one time it was grandly called the English scarab, which is a bit odd because this exceedingly handsome beetle no longer occurs in England, or anywhere in the British Isles for that matter, unless you count Jersey and Guernsey, and most people don’t. The name was coined, slightly after the fact, it has to be said, when conservation organisations were writing biodiversity action plans for various charismatic endangered species during the 1990s. Everything needed an English name, otherwise journalists and politicians, let alone the general public, wouldn’t have a clue. By then it was already considered extinct in the UK. It was always very rare, and was last definitely seen here when a specimen flew into the entrance hall of the Juniper Hall Field Station near Box Hill, on the North Downs in Surrey, at 10.30 p.m., on 27 May 1955. This area of ancient grazed chalk downland would have been perfect.

I grew up on the South Downs, in East Sussex, and this was always a beetle I half fancied I might find. In my dreams. Except my dreams just might have come true, if I’d been lucky enough. In 1994 Peter Hodge was given a specimen of Copris found in a glass-topped display case of insects, made at some time past by a local naturalist, H.L. Gray, and later donated by his widow to Lancing College, in West Sussex. The tantalising handwritten data label stated ‘Lancing Ring, 19.9.60’. The first thought was that this might refer to 1860, when this species was known from nearby Shoreham, but the beetle had been mounted on the back of card cut from some printed material; from the typography, and other beetle mounts in the collection, it could be dated directly to 1960 (Hodge 1995). I had been kicking around these exact same chalk downs a decade and a half later, but never saw it. I tried my darnedest though.

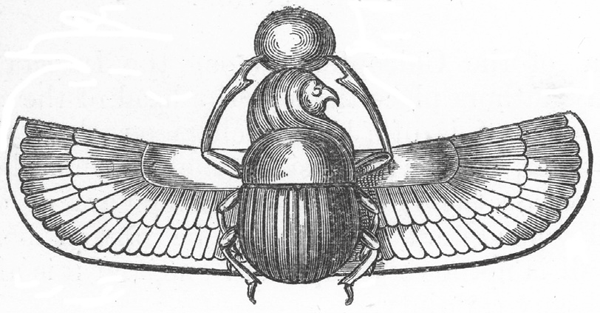

Fig. 30 A unicorn amongst beetles, Copris lunaris, marvellously structured, enchantingly elegant, mythically rare. An affectionate engraving from Michelet (1875).

At least it is pretty widespread in France, and I got a great thrill finding it in the meadowland attached to a sun-bleached holiday gîte in southern Burgundy a few years back. I did not need to self-bait for it. It’s a magnificent creature: the male has a long back-curved horn on its head (a feisty tunneller, no doubt), the female a slightly smaller one. Its body is sturdy, elegantly rectangulo-subovate, gently ribbed along its wing-cases, delicately dimpled across the thorax, entirely a lustrous black, looking for all the world as if it were sculpted from obsidian. I’m going to commission my own scarab amulet, based on this mythically rare beast – a unicorn amongst beetles.

Another unicorn, but one that does turn up in Britain occasionally, is the almost globular Odonteus armiger. Whether it is a dung beetle or not is still being teased out. Current consensus is that it feeds on subterranean fungi. It has been found burrowing down 30–40 cm to get at them. There was a notion, not very convincing, that it is associated with rabbit warrens, the fungi somehow benefiting from the buried crottels, implying that the beetle was an indirect coprovore. Old beetle monographs state things like ‘In dung; generally taken on the wing.’ They also like to relate things like: ‘Mr Mason’s specimen [Croydon, 1880s] is one of the most recent instances of its capture in Britain; seeing a beetle flying past, he knocked it down with his stick to see what it was, and found it to be this very rare species’ (Fowler 1890). I’ve never seen one alive, but occasionally I hear of a sighting, and am lost to a moment of quiet reverie. And I wonder if, in my dotage, I will be as accurate with my cane, as I potter about in the grounds of the care home.

These are, admittedly, unlikely finds, but the common dor beetles (Geotrupidae) are just as impressive. When my family first moved to Newhaven, in Sussex, after my father’s office relocated to nearby Lewes in 1965, we had the South Downs on our doorstep. It wasn’t long before we were off exploring the rolling hills around South Heighton, Tarring Neville and Firle. Many of these were grazing meadows and although it would take a few more years before I really got stuck into dung beetles, I well remember Dad and me finding scores of Geotrupes on one evening stroll to nearby Bishopstone.

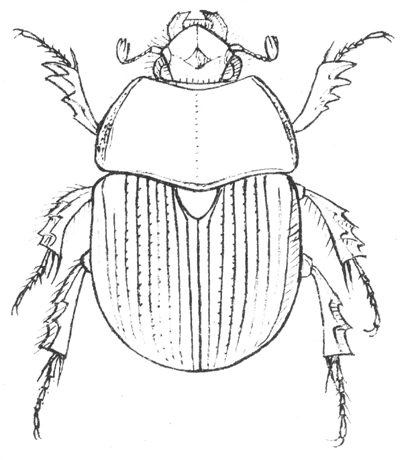

Fig. 31 A dumbledor, or dor beetle, Geotrupes, a picture of the robust earth mover.

They were buzzing about, low, bumbling, over the grass, and we didn’t need a net to catch them. I was astonished at their power, as one clawed its dumpy clockwork way out of my cupped hands, pushing its smooth blunt head forwards, as it heaved with its broad toothed legs. When it took to the air it was like a miniature helicopter taking off from my palm, and I can almost feel the memory of that downdraft on my skin now. And somewhere at the back of my brain is the gentle buzzing note they make as they fly past; the sound of a summer evening in a childhood of blessed memory.

The name ‘dor’ is derived, according to my dictionaries, from the sound of the insects flying, and although these books often suggest bumblebees (or ‘humblebees’), any entomologist worth their salt will tell you that bees hardly buzz when they’re in flight. ‘Dor’ definitely applies to these giant dung beetles. I’m not sure if it was dung beetles or bumblebees that inspired J.K. Rowling to call Harry Potter’s headmaster Dumbledore (using the later alternative spelling), but when I snatched one out of the air on the banks of the Wolfgangsee near Salzburg in 2013, my Austrian in-laws were immediately familiar with the professor’s name. They remained politely enthralled as I enthusiastically introduced them to the ecological concepts behind the natural recycling of decaying organic matter.

Although it sounds a bit like a bottle of craft ale or a cross-Channel ferry, the pride of Kent is actually a beetle. Emus hirtus is an enormous furry rove beetle; again it’s very rare, and I’ve never seen one. It is not, however, extinct, and has been reported regularly, if exceedingly sporadically, in the Elmley Marshes National Nature Reserve, on the Isle of Sheppey. It first turned up there in the gents’ toilets near the car park in 1997, but puts in an occasional appearance for the reserve wardens or visiting naturalists. A flying specimen was also reputedly caught by one of the reserve staff, on his bare chest, as he motored round the meadows on a quad bike.

The rove beetles are an exceptionally successful group of insects. They have very short wing-cases, under which tightly folded membranous flight wings are protected. This gives them the double advantage of having an extremely flexible body form to wriggle into tight spaces, but still retaining the ability to take to the air. Plenty live in dung, from the flat slow dung-feeders such as Oxytelus and Anotylus, to the predatory Philonthus and parasitoid Aleochara. Emus is a fierce predator, a fast and efficient killing machine that will tackle flies, maggots, grubs, dung beetles; indeed whatever it can get its teeth into. It only ever seems to appear at fresh cow dung, and coleopterists visiting Elmley can be identified by their insistence on closely following the cow herds around (or being closely followed by the cows according to RSPB naturalist Rosie Earwaker), in the hope of spotting Emus at a steaming pile of excrement only minutes old (Telfer et al. 2004).

Unlike the smooth and shiny scarabs, Emus is covered with grey and gold fur, and when it flies it looks just like a manic bumblebee. Accounts of its activities at the pat vary. The late A.M. Massee (a respected and knowledgeable entomologist, but also a notorious raconteur) reported that he had seen Emus fly down to a fresh liquid cow pat, dive in and emerge a short time later, its coat of luxurious golden hairs remarkably unsullied. This is slightly at odds with the advice given by Föreningen SydOstEntomologerna (South-east Sweden Entomological Society) which suggests that to catch Emus ‘smack the beetle with a firm hand down into the smeary dung, find it by digging and put it in your tube with some absorbent tissue’, implying that the beetle becomes mired. I’m sure they washed their hands afterwards.

I suspect that Emus avoids clogging its fur coat by pushing under the dung, amongst the grass root thatch, rather than trying to swim in the gloop. This is exactly what the slightly smaller, and slightly more demure, Ontholestes tessellatus does. It’s not so large as Emus, but is still attractively decorated with a variegated pattern of glistening metallic brownish hairs. It too seems to avoid becoming sullied, despite a similar predilection for glistening, ultra-fresh dung. Ontholestes is always intent on catching flies and is hyperactive on the fresh dropping, flicking backwards and forwards with a frenetic, jerky gait.

Other show-off rove beetles to look out for, disporting natty black and red tones this time, are Philonthus spinipes, a recent spiny-legged arrival into Europe from the Far East, and Platydracus stercorarius, the generic name of which aptly translates as ‘flat dragon’. Again, they are fast, agile hunters, gone in a twinkling.

FLIES – THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE BUGLY

Finding the yellow dung fly, Scathophaga stercoraria, wins nobody any prizes. This is a common, verily ubiquitous, insect and, just like me and the other keen first-year university students in Ashdown Forest, all you need do is sit close to a fresh animal dropping, and they come zooming in. The males, with their fuzzy yellow plumage, are very distinctive, but amongst them are the olive grey females. To be honest, it’s easier to find the females sitting about on the herbage; here they are hunters, attacking and eating other small flies. As soon as they arrive at the pat, though, they become embroiled in a mêlée of over-amorous males. After the pat has dried a little, and developed a tough fibrous rind, the adult dung flies will have moved on, but lift up the lid of the pat, and long, white, narrowly conical maggots squirming in the ooze at least show that the flies have done their job here.

It’s when the dung starts to dry out that one of the most charismatic of flies may deign to visit. The hornet robber fly, Asilus crabroniformis, is northern Europe’s biggest fly, and although its black and yellow colour scheme may evoke a fear of waspish stinging, it is the mouth end that delivers the danger. This ferocious predator sits atop a dry pat, darting up rapidly to snatch flying insects out of the air. It is quite capable of wrestling a dor beetle and coming out on top. It has strong bristly legs, which it uses a bit like a grapple, and sharp piercing mouthparts with which it skewers its victim.

Fig. 32 Asilus crabroniformis, disarmingly illustrated by Shaw (1806), but it is the mouth end that does the damage, at least to flying dung beetles, not the pointed tail.

The family move to Newhaven soon brought this large insect to my attention, and I even have a vague memory of it appearing in the garden once or twice – though not on dung. The last time I saw it was in Poverty Bottom, one of the softly rounded glacier-hewn valleys through the South Downs behind Denton, where I sat one fine summer day of the school holidays, watching them taunt dragonflies and eat the occasional blow fly. One of our neighbours walked past, with his dog, and after watching me stalk a cow pat and swat my net over the top of it, enquired politely what I intended to do with the dung now that I had caught it. I hope I was able to make his eyes bulge with wonder, or fear, as I showed him the monstrous creature in the folds of the net.

For most of the other dung-feeding flies, I expect people narrow their eyes in disgust and loathing. The most obvious ones on the freshly dropped stool are greenbottles (Lucilia), bluebottles (Cailiphora) and mottled dung flies (Polietes). They can form a raucous bristling mass over the dung, taking to the air in deafening buzzing clouds if disturbed. Looking at a dropping alive with flies, it always amazes me that the links between excrement and fly-spread diseases took so long to be recognised. Mind you, they are still misunderstood and misrepresented today.

None of the flies mentioned above, nor for that matter the common yellow dung fly, Scathophaga stercoraria, or a whole host of others bombing or bobbing about on the pat, ever cause any real harm. They do not come indoors, are not attracted to human food and are not implicated in the spread of human diseases. They might fly irritatingly about your head (face flies, Musca autumnalis), or try to bite you (stable flies, Stomoxys calcitrans) when you’re off walking through the countryside, but that’s another matter. The only dung-breeding flies which do come indoors are the appropriately named house fly (Musca domestica) and lesser house fly (Fannia canicularis). Fannia is the small pale grey fly you often see flying in erratic zigzags beneath the hanging light, then landing adroitly upside down on the bottom of the light bulb. Fannia will not, though, fly down to land on your food. It is simply marking out a three-dimensional aerial territory in which to meet a potential mate; away from your kitchen these flies zigzag about under spreading branches or in the shade of an overhanging shrub. You will never see one on the dinner plate.

This, unfortunately, cannot be said for the house fly. When bacterial and microbial diseases first began to be understood in the late 19th century, it was the house fly which became the target of insect plague rhetoric. It wasn’t long before more than 100 types of bacteria, virus and protozoa had been found hitching a lift on house flies, and a single house fly was found carrying 6.6 million bacteria (Hewitt 1914). Along with mosquitoes (which thankfully do not breed in dung), the house fly became public enemy number one; it was the insect menace to which book and poster campaigns were targeted. And all because it bred in filth.

Oddly, you don’t find many house flies buzzing around in grazing meadows. Out in the wild they tend to be rather secretive. They also prefer manure heaps to fresh pats. This has had the strange effect of making them much less of house flies in the 21st century. In Britain, at least, they are no longer house flies, but farm flies. In 17 years of living in my current house in south-east London, I have found a house fly indoors just the once. I blamed the over-aromatic state of the guinea-pig’s hutch, just outside the back door, for this. At other times there just is not the manure lying around any more. Along with the lesser earwig, house flies have declined in towns and cities, following the decline of horse-drawn transport. But whenever we go on holiday to rural France, we spend hours each day patrolling with the flip-flop of doom, leaving a trail of swatted corpses behind us.

House flies lay batches of about 150 eggs at a time, with half a dozen batches over a fly’s lifetime of a week or a month. The maggots are fully fed in 3–30 days depending on the ambient temperature. A week or so later and the new adults have emerged. In temperate Eurasia and North America there can be a staggered range of 10–12 generations a year, but since they overlap the flies are constantly on the wing. In the tropics the fly is continually brooded and the flies can easily reach pest proportions. In Australia the house fly is replaced by the bush fly, Musca vetustissima, and if we thought we knew pest proportions in the Old World, European colonists to the southern hemisphere were totally unprepared for the multitudes on a biblical scale presented by this diminutive insect. The bush fly gets more prominent treatment in chapter 10.

Back at the manure heap, the suppurating fermentation is attracting lots of flies, and one of the most dramatic is the drone fly, Eristalis tenax. This large brown and orange hover fly is so named for its close resemblance to the male (drone) honeybee. It lays its eggs in nearby ditches, where the dank liquid outflow from the manure, or seeping spillage from the slurry lagoon, mixes with water draining from the fields, and also in streams where raw sewage is still discharged. The large pale maggot has a long ‘rat tail’, the telescopic breathing tube with which it takes air from the surface.1

The ancients understood a little about scarabs, but were not quite so up on fly ecology. The drone fly is the bugonia or oxen-born bee of myth, fable and the Bible. Until well into the Middle Ages it was authoritatively reported that a swarm of bees would appear, by spontaneous generation, from the body of a cow, especially one which had been bludgeoned to death, and had its nose and throat blocked to stop its soul leaking out. Feral honeybees will nest in hollow trees and rock crevices, but not in the rank putrescence of a rancid corpse. To the drone flies, though, liquefying carrion or draining faecal sludge are close enough decaying organic matter for either to suffice.

Samson, strong-man of the Israelites, was similarly mistaken when, wandering through the desert, he came across the dead body of a lion, buzzing with insects. He later offered a riddle to some truculent in-laws (uncircumcised Philistines): ‘Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness’ (Judges 14:14). His implication was that something edible (‘meat’ in an archaic sense) came from the predator, and that the strong lion was now a source of honey. Of course these were drone flies, nothing to do with honeybees – the mistake continues to this day, much to the frustration of picture editors worldwide. The myth of the oxen-born bee had been sorted out by the 19th century (Buckton 1895), but this hasn’t stopped sugar manufacturers Tate & Lyle using the quote, along with a dead lion and a swarm of ‘bees’, on tins of their famous golden syrup. Go and visit the factory at West Silvertown, in the old London docklands, and you’ll see a representation of the tin, the size of a transit van, projecting from the corner of the building. Bonkers and brilliant.

I realise we’ve ambled quite a distance from rural grazing meadows to industrial North Woolwich, so in an attempt to reboard the train of thought, I’m going to retrace my steps back to Poverty Bottom and the South Downs near Denton. It was somewhere around there, back in the late 1960s, that I first came face to face with the noon fly. Apparently Mesembrina meridiana, gets its 12 o’clock meridian name from its habit of basking in the full sun at the height of the day, and that’s just about right. If dors are the symbols of dusk, then this huge, black, shining fly is the embodiment of the midday sun. Here it sits, in the crook of a stunted hawthorn bush, or on a tree trunk, soaking up the warmth, darting off rapidly if disturbed, but often returning a few moments later to its perch. It hardly ever visits dung; it doesn’t need to.

In contrast to the profligacy of a house fly’s many hundreds of eggs, or even the many scores laid by the yellow dung fly, Mesembrina may only lay five or six eggs, one at a time, a day or two apart, in the freshest dung it can find. The large egg has a spine-like process at one end, possibly to give it buoyancy in the liquid medium. The fly’s frugal egg-laying policy echoes the slow but careful brood strategy of the large roller scarabs, but unlike them Mesembrina offers no maternal care to her young. The single egg deposit means a bigger egg, and a bigger hatchling maggot; and although this one will eat the dung itself, if there is nothing else around, it much prefers to eat other larvae. It is a formidable predator. Laying more than one egg per pat would be a counterproductive effort, as one would more than likely eat the other. By getting in quick, the female noon fly is trying to ensure that her single offspring will be top maggot, the biggest fish in the pond. Consequently, with only one egg to lay each day, Mesembrina can afford to sun herself leisurely most of the time. Taking a siesta.

There is no such luxury for the ant flies. The Sepsidae have nothing to do with ants, of course, but vaguely resemble them by virtue of their small size, shiny, black, narrow-waisted bodies and large bobble heads. Their most distinctive feature is a small black spot at the end of their wings. These are all the more prominent due to the flies’ habit of slowly waving their wings about in a deranged semaphore. Sometimes both wings sweep together, sometimes they alternate, sometimes they gyrate in what looks like completely asynchronous chaos.

The purpose of the wing-waving is still unclear. In other flies such activity is closely associated with mating, and forms part of a complex who-are-you? mate recognition dance. But sepsids dance even when there is only one sex (males) about. Sometimes there are clouds of them, with aggregations of 30,000–50,000 recorded. These may be mass emergences of adults following hibernation. All-male clouds suggest lekking, a behaviour where males congregate in one spot to attract females. The fact that these congregations have a distinctive smell (at least to the human nose) suggests there may be some female-attracting pheromone scent involved. When I sat down in a grazing meadow near Hastings to eat my packed lunch one rather dull April day in 1976, I do not believe it was the odour of my ham sandwiches, or flask of tea, which brought out the cloud of many hundreds of wing-waggling sepsids from the grass tussock I was leaning against. Within minutes they were all over my backpack, crawling up my legs, getting in my hair. It was all very peculiar. I think I was just there in the right place at the right time to see this strange phenomenon. Fresh dung can attract huge numbers, although they have to be careful of the larger and much more dangerous yellow dung flies, which could quite easily mistake a sepsid for a tasty snack.

The horse bot fly maggot travels to the dung by a convoluted and circuitous route. It arrives already packaged in the dung, when it is dropped by the horse, having been living quite happily inside the animal’s digestive tract for the last few months. It’s tough exterior is completely immune to the plant-digesting processes going on in there. Gasterophilus intestinalis (that’s Graeco-Latin for ‘intestinal stomach-lover’) is well named. It started out as a narrow white egg, one of up to 1,000 glued individually onto the hairs on the horse’s flanks or front legs by the female fly, using a neatly upturned egg-laying tube at the tip of her abdomen. As the horse licks itself, the eggs are stimulated to hatch immediately and the tiny larvae burrow into the mucosal membranes of the poor animal’s tongue and mouth. After about a month they allow themselves to be swallowed, and now half burrow to the lining of the horse’s stomach using a series of hooked barbs around the mouthparts and skirts of backward-pointing bristles around the body. For the next 9–12 months they chew away at the stomach membranes, and with clusters of many hundreds of them in some victims, they can cause the hosts quite some distress, what with ulceration, possible infections and interference with normal digestion.

Eventually, when fully grown, the now large (1.5–2.0 cm), fat, dirty cream, bristly larva relinquishes its hold on the stomach wall and is passed down with the faeces, through the intestines to exit the horse and land in the field. Here it pushes out and burrows down into the soil, grass thatch or dried manure to harden into a dark spiky pupa. The adult fly emerges a few weeks later in late summer or autumn.

When I uncovered a freshly deposited maggot in a mound of horse droppings in a field between Fairwarp and Duddleswell, north of the equally unlikely sounding Uckfield, in East Sussex, in August 1974, I could not for the life of me imagine what it might be. By then I reckoned myself quite an expert on insects, and could tell it was some sort of giant fly larva, but its identity perplexed me. So I did what any sensible person would do – I took it home to rear it. Of course the secret to rearing unknown larvae is to take as much of the foodstuff too, so I stowed it in my now empty sandwich box with plenty of fresh horse dung. Simple.

I can’t quite remember whether my Mum had anything to say about the matter. The exact details of our exchange evade me now. Thankfully it pupated within 24 hours and I was able to transfer it to a jam-jar of less pungent, therefore less complaint-worthy, garden soil. A fine orange and brown furry fly emerged later that year. I had never seen anything like it. I wonder if I will ever see it again. By 1974 this was already a scarce insect because it was already being widely persecuted, on the way to being eradicated. That’s the trouble with agricultural pests, especially ones causing grievous bodily harm to horses; they somehow don’t qualify for conservation status. Instead, they attract the attention of pharmaceutical companies, trying to poison them. The flanks of horses are now drenched with insecticide to kill the eggs. More chemicals are given as oral gels, liquids or feed additives to kill the maggots living in the gut. In Britain, at least, where there is no wild horse-like animal to act as a natural reservoir, it does not take much to eliminate the horse bot. It may still linger where feral horses roam, chemical-free, on Dartmoor or in the New Forest, but even here doped feed can be left out for them if the fly ever came to be regarded as a local nuisance again. Although this is not a dung fly it is, nevertheless, a fly associated with dung, but for how much longer? The veterinary chemicals given to farm animals will have a darker, more profound effect in chapter 10.

What route the tiny shining spider beetle Gibbium aequinoctiale took into the deep underground passages of the Silverwood Colliery on the outskirts of Rotherham remains unknown. They were discovered here in the 1990s. Coal miner Andrew Constantine noticed them, because his brother Barry was an entomologist, and he knew that anything eking out a living 800 m below sea level in the dark, disused tunnels was bound to be something unusual. It took several years, though, before he could be convinced to collect any specimens, because the beetles only occurred in the old roadways that the miners used as latrines, and here they were feeding on human excrement (Constantine 1994).

A deep-shaft coal mine is not your average workplace; there are no lavatories, toilets or restrooms, no plumbing, no water, no sanitation of any kind. Down at the coalface for hours on end, the miners took whatever convenience they could when the need arose, so they used the abandoned roadways as unofficial earth closets, except there was no earth down there either. The walls were bare coal, the floors crumbly mudstone. Unlike latrines on the surface, which might be leached by rain, visited by dung beetles and flies, and eventually absorbed back into the environment, down in the cold coal underworld no dung recycling took place. Instead, the stools slowly began to dry out until they reached the consistency of fruit cake. This is not a faecal incarnation represented on the Bristol stool chart. It was in this almost non-decaying organic matter in which the beetles were breeding – hundreds of ’em. Since this unusual habitat was first noted, specimens of the beetle have also been found in similar circumstances in coal pits in Staffordshire and Durham.

Several species of spider beetle are known to feed on fallen seeds, mould, pollen stores in bees’ nests and stored foods in human habitations. They are adaptable feeders, and many have become cosmopolitan household pests by invading our larders. It was suggested that down the pit they may have been feeding on spilled food, but who eats their sandwiches in the lavatory? As Mr Constantine observes: ‘The miners understandably take their meal breaks well away from these roadways, so there is no food debris for the beetles to feed on.’ Pit ponies were used in the mines from their opening in the 19th century until about the late 1960s, so one scenario is that the spider beetles somehow arrived with the ponies’ feed and straw bedding. However they got there, the Silverwood colonies of G. aequinoctiale are, as far as I know, the only coprophagous members of this family.

There are plenty more deep mysteries to fathom. Where has Aphodius subterraneus gone? This once widespread dung beetle has vanished from the UK; the last one was recorded at Scarborough in 1954. Why is the scarce northern and western British form of the dor beetle Trypocopris vernalis shiny blue-black, but in southern Europe a rich iridescent green? Does anything specialise in mole dung? How did a specimen of the South African Onthophagus flavocinctus end up dead in a puddle on a bridle path in the middle of East Sussex in 1967? If enough people become interested enough in dung and its inhabitants, who knows what new and exciting discoveries are still out there waiting to be made.

1 Eristalis really does like the most rancid material. Geoff Hancock was pleased as punch when he found himself ankle deep in a moist tapir latrine in Costa Rica, and took the opportunity to collect and breed out several hover fly larvae, including that of Eristalis alleni, the immature stages of which had never been seen before.