Ruling Regions, Exploiting Resources

INTRODUCTION

Since Moses Finley shredded the modernist views of Michael Rostovtzeff, the consensus model of the Roman economy has tended to emphasize its primitiveness and underdevelopment, its subsistence base, and its relative lack of growth.1 Finley was strongly influenced, of course, by Karl Polanyi’s theoretical work on the embedded nature of ancient economies.2 Polanyi is also to be credited for introducing to the debate on the ancient economy the social structures of redistribution and reciprocity, and these have become important concepts alongside market exchange in our exploration of the Roman world.3 The formalist/substantivist debate that Polanyi’s work sparked has reverberated far longer in ancient history than it has in the social sciences and I have no wish to add to it. However, it is worth stating that it is possible to challenge Finley’s minimalism while at the same time endorsing parts of the substantivist view.4 Indeed, since Keith Hopkins made his first revisions to the minimalist model in 1980, the pendulum has started to swing back toward a more positive appraisal of the scale of activity and the possibilities of growth in the Roman economy.5 A compromise position is to recognize that the Roman economy possessed both primitive and progressive characteristics.6 As Henk Pleket has written, “primitive pre-capitalistic features were typical of large sectors of the economy … but at the same time … there were ‘niches’ of a more capitalistic economy, characterized by structural longdistance trade in staples (wine, oil, grain) and luxuries (textiles, spices, marble) and by production of those goods for the market.”7

Markets, both physical and conceptual, are increasingly recognized to have been of sophisticated type—at least at certain times and places.8 It is perhaps time that debate on the Roman economy moved on to discuss other issues, such as how this hybrid economy came into being and how it functioned.

Another important question concerns the nature of intervention by the Roman state in the economic sphere. Modernists have tended to extol the economic benefits of empire—though this view is also symptomatic of the modern colonial discourse. As Jules Toutain expressed it, “Economic life, within the actual bounds of the empire was at once national and international. … This very important evolution was favoured … by the fact of the empire itself and by the benefits which it shed for at least two centuries on all countries subject to Roman rule.”9

Primitivists have also let the empire off lightly by insisting on the limited impact of Rome on peasant subsistence economies.10 A key conclusion of this chapter, as we shall see, is that state intervention was in fact significant both in terms of scale and impact.

The work of Hopkins is of particular importance for my theme in that he attempted to establish a series of propositions about the Roman economy that focused on the impact of taxation on the development of trade.11 Specifically, Hopkins argued that frontier provinces were often net recipients of taxes raised elsewhere in the empire and that core Mediterranean provinces were net exporters of tax. In order to furnish the demands for specie, the tax exporting provinces were obliged to expand their involvement in interregional trade, with significant consequences for the Roman economy overall. In reaction to some critical responses,12 he returned to the theme in a 1996 article, defending his position and enlarging his view.13 Both articles are excellent examples of how theoretical studies can be presented in clear models, backed up by imaginative use of order-of-magnitude estimates and comparative approaches. Although my overall conclusions here will place a different emphasis, I endorse Hopkins’s general point that there was a potentially significant relationship between the economic exactions of the state and the overall relative patterns of economic growth and stagnation.

In recent years, debate has started to explore the tensions between global and local aspects of the Roman economic world.14 Peter Temin has stated, “Finley was wrong; ancient Rome had an economic system that was an enormous conglomeration of interdependent markets,”15 a point supported by Greg Woolf, who has made a strong case for identifying significant regional economic foci.16 There has been some fertile engagement with “new institutional economics” in recent discussion about the role of the state in the imperial economy.17 However, there is still a tendency for commentators to write about the Roman economy in the singular. I shall argue in this chapter that the economy is not only best understood as an agglomeration of globalized regional economies but that we can also define a series of major mechanisms at work that governed discrete areas of economic activity. In particular I shall focus on the role of the state as a motor of economic activity through its status as an imperial power. I am going to construct some simple models of my own, built around colonial discourse analysis, rather than complex economic theory. It needs to be stated at the outset that I am aware of the dangers of oversimplification inherent in such an exercise. Detailed consideration of individual economic instruments, such as the imperial fiscus or the taxation system, will no doubt reveal greater complexity due to regional specificities or evolution over time.18 The main purpose of this chapter, however, is not to outline a new general model for the Roman economy but to reignite debate about the economic face of Roman imperialism.

I want to start by contrasting two views on the economic face of colonialism:

Britain … had no reputation as a source of wealth. It is very doubtful that wealth was expected to accrue from its conquest, at least after the initial spoils of war had been claimed by the invading army. The empire’s provinces were an accidental by-product of politically motivated conquest and were rarely viewed as an economic resource to be exploited systematically.19

An imperial power which has just acquired a new province faces the huge task of organizing the territory and implementing its power. … Once the new imperial power has quelled any substantial military resistance, it needs to carry out some sort of census or survey to evaluate what it has acquired, make sure that the necessary communications systems are in place, and above all set up a system for the extraction of surplus by means of taxation. This “settlement” is the material face of the colonial project as a whole: the creation of order, government and infrastructure, often with ideological trappings of paternalism and altruism.20

Empires exploit territory and people, and there tend to be common patterns in the sequence of events that follow armed conquest of a region.21 When the French general Thomas-Robert Bugeaud set out to crush resistance in Algeria led by Abd el-Kader, his treatment of defeated tribes included a variety of measures—burning of settlements and crops, forced military recruitment, taking of hostages and female prisoners, exaction of tribute, forced resettlement and reallocation of lands, disarmament, placing of garrisons and imposition of military road networks, requisition of transport animals, and demands for labor corvées.22 This account of the multiplex exploitation of people and resources could equally be applied to the Roman Empire. The Roman sources, and the (rare) testimony of subject peoples such as the Jews, certainly suggest that the Roman state had an extraordinary capacity for swallowing up the wealth of the world.23 Yet many modern scholars have chosen to downplay the economic underpinnings of Roman imperialism.24

While I would agree that the motivations behind further conquests in the Roman Principate were often highly political, the emperors sought not only military glory but also to fulfill their responsibilities to keep an expensive show on the road.25 “Good emperors” were expected to balance the budget—that is, to ensure that revenues met or exceeded core expenditure—and to have control of financial records.26 Moreover, the annals of Roman history were full of details of the spectacular spoils of expansionism: Carthage’s indemnity after the Second Punic War was the equivalent of 100 million sesterces; in the second century BC Antiochus paid over 340 million sesterces; Pompey the great claimed to have raised provincial tax revenue by 140 million sesterces as a result of his Eastern triumph.27 As we shall see these were very substantial sums when set in the context of the overall imperial budget. Those at the center could not afford to ignore the potential importance of conquest for the imperial coffers (see fig. 5.1).28 The creation and maintenance of empire has ultimately to be linked to the exploitation of resources.29

FIGURE 5.1 The spoils of victory (short-term): the temple treasure from Jerusalem paraded through the streets of Rome as part of the triumph of Titus.

Comparative studies suggest that the economic encounter of colonizer and colonized is a defining aspect of most imperial systems. Michael Given’s perceptive book The Archaeology of the Colonized could equally be subtitled “the archaeology of taxation and tax evasion,” as it deals with the competing economic forces of imperial exaction and individual strategies of fiscal subterfuge.30 The difficulty for archaeologists is to demonstrate conclusively the traces of this recurrent battle, when so little of the written documentation of the census and taxation systems survives. Yet to ignore the impact of the encounters between subjects and the tax man is to turn our backs on what must have been key experiences of empire. In the Roman world, paying taxes was not a neat payroll deduction but an act of “public dispossession” on the part of an imperial agent. As Given writes, “Through the physical actions of paying taxes and working in labour gangs, people experience imperial rule in their bodies.”31 Taxation and other exactions thus represent the quiet violence of empires. In the Roman Empire, exploiting resources covered a wide range of activities in addition to taxation, including measures to exploit land, natural resources, and, above all, the labor of subject peoples. A recurrent problem for empires concerns how to promulgate and enforce rule-based order. Opposition to imperial systems is often rooted in economic and power inequalities, and while these inequalities are integral to the efficient functioning and maintenance of the empire, they are also a constant danger to its existence.32

The Roman Empire is sometimes presented as inefficient and disorganized in its attempts to collect taxes—witness the fact that practice varied hugely from province to province and that periodically there were general write-offs of arrears—with Hadrian seemingly absurdly generous in this respect in canceling 900 million sesterces of arrears.33 Yet this apparent failure could be taken another way—the Roman Empire was able to remit taxes periodically precisely because of its overall success in assessing tax liability across all provinces and a wide range of activities. Raising taxation from large and diverse territories is never easy—as the British Empire found to its cost in Boston—and by the standards of the ancient world, Rome was pretty good at it.34

Monetization and the rate of circulation of coinage are clearly important issues of debate, not least because of the extent to which the Roman Empire collected tax and rent in coin (see fig. 5.2).35 But it is clear that the state also extracted resources in other ways, too: in kind, through monopolies of key natural resources and in terms of labor, transport, and liturgical commitments.36 Thus, if I seem to give less attention here to coinage that you might expect, this is not for lack of interest or relevance but more so that I can open debate on a wider array of ways in which the empire was exploited economically.

FIGURE 5.2 The spoils of victory (long-term): rents being collected in coin and recorded by scribes in a funerary relief from the Moselle region.

In this chapter, then, I want to turn away from individual economic agents and focus on the state and its economic needs and systems. Just as the globalizing reach of Rome had an important role in the emergence of discrepant social identities, it also spawned discrete economic “identities.” A recent paper by Lisa Fentress has tried to refocus the debate about the Romanization of Africa around a fuller appreciation of the economic effects of empire and the process of disembedding that followed Rome’s attempts to mobilize the economic potential of its territories.37

While I reject her use of the word Romanization to describe this process, I think that Fentress and I are both broadly concerned with the same phenomenon—the behavioral consequences (intended or otherwise) of an empire’s efforts to exploit its subjects economically.

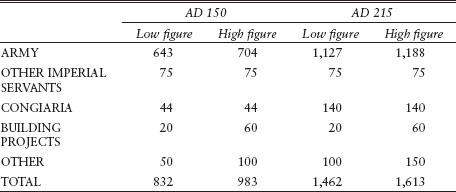

Estimates of imperial annual budget in millions of sesterces

Source: Duncan-Jones 1994, 45.

Note: To put this annual budget of around HS1,000,000,000 in perspective, we should first note the minimum census qualification for a senator of HS1,000,000.

THE IMPERIAL BUDGET

The cost of running the Roman Empire must have been a major preoccupation of those at the center of power. One of the paradoxes of the Roman Empire is that the costs of its conquest were drastically lower than the recurrent expense of its defense thereafter. The progression from an annually levied army of generally less than ten legions strong to a permanently maintained force of twenty-five to thirty legions, plus equivalent numbers of auxiliaries (for a total force of between 300,000 and 500,000 men), was a singularly important economic shift. Modern European states did not acquire similar standing armies until eighteenthcentury France or nineteenth-century Britain—in the medieval era, the resourcing of periodic levies of tens of thousands of troops for war was a major challenge to European states.38 In this light, the Roman state’s economic achievement is striking.

There have been few attempts to calculate the likely revenues and expenses of the Roman Empire at the height of the Principate.39 Table 5.1 suggests that a round figure of about 1 billion sesterces may have been required by the mid-second century AD. Although there are large lacunae in our knowledge, military expenditure was evidently a huge and recurrent element of the total. Richard Duncan-Jones’s figures are slightly higher than some previous estimates; these vary from as low as 300 million sesterces under Augustus to around 900 million in the Severan period.40 Taken together, the cost of the army and of salaries for officials involved in provincial or central government functions made up over 85 percent of the estimated total budget. States have a number of options over how to fund warfare and organize supplies for armies: seizing, making, buying, coercing, or taxing.41 For the Roman state, with its habitual approach to war in the Republic and its large standing armies in the Principate, ad hoc measures had to cede increasingly to systematic levying of tribute. This was the bottom line of running the empire—taxation simply had to deliver at least these levels of resources. The comments attributed to Cerialis by Tacitus convey the message clearly: “[N]o peace … without arms, no arms without pay, no pay without tribute.”42 Despite the many uncertainties in our knowledge of the imperial budgets and of revenues, it is clear that emperors were in a better position to understand their financial position because of detailed record keeping and a growing bureaucracy under control of financial specialists, the secretaries a rationibus. “Bad emperors” could impact negatively on their secretariat’s best efforts by emptying the coffers and cause headaches for those who followed after (succession was always an expensive moment for any princeps). Pertinax found only 1 million sesterces in the treasury on his accession, a fact that contributed significantly to his rapid fall from grace with the praetorian guard.43 The emperors Nerva, Marcus Aurelius, and Pertinax were obliged to auction off artworks and furniture to raise emergency funds.44 But by and large the system worked tolerably well in the first two centuries AD.

It is clear that there were major differences between the Late Republican tributary systems and the more regularized direct rule and taxation of the Principate; further changes occurred in late Roman times.45 But “bean counters” were common to all phases of Roman imperialism, as were fraud, bribery, malpractice, unjust impositions, and tax evasion. Many one-off taxes—such as those on trade goods at borders, on slave purchases, and on inheritance were around 5 percent of the value of the goods. These base levels of taxation may seem relatively low, but recurrent tribute on land was much more varied and could be as high as 25 percent, and “rents” on imperial estates in Africa, for instance, were levied at 33 percent of the main crops produced. In Egypt it is clear that there was a multiplicity of different taxes and that arrangements varied wildly within the province and across social groupings.46 In Judaea there are also hints in the Talmud and other ancient sources of heavy taxes being endured.47 The varied nature of provincial arrangements, often building on preexisting structures, and the accretion of additional exactions over time cumulatively represented a burden for many communities—made worse by the fact that some groups and communities were much more favorably treated. In the face of provincial disquiet at the impositions, Roman writers were conscious of the need to stress the necessary link between taxation and security: “And since it is quite impossible to maintain the empire without taxation, let Asia not begrudge its part of the revenues in return for permanent peace and tranquility.”48

For much of the Republican imperial age, the state took a somewhat backseat approach to taxation, appointing tax farmers (publicani) or enlisting local authorities to act on Rome’s behalf. In the Principate, the publicani were replaced by a combination of imperial financial officials and local agencies (urban magistrates or councils who oversaw collection). The conventional view is that the Roman officials simply dictated the sums required from a particular city or region and left to “local responsibles” the more complicated decisions about how that liability was to be apportioned to individuals.49

The Achaean town of Messene in the first century AD appears to have had an overall demand equivalent to 400,000 sesterces.50 The inscription that records the arrangements for dividing this large demand among the constituent groups in the town’s population reveals that the tax represented about 2 percent of the capital value of land. Evidently detailed census records underlay both the state’s appraisal of regional tax capacity and the calculations of local officials in apportioning shares of this across the community. Knowledge was thus crucial to power.51 The Messene inscription records how, under the watchful but approving gaze of the Roman praetorian legate, the council secretary Aristocles reported to the assembled townsfolk his success in collecting in 83.5 percent of the required total. Some of the local inhabitants appear to have been more successful than others in evading their obligations. For instance, Roman citizens and aliens living at Messene were responsible for 10 percent of the tax liability, but 33 percent of the net arrears. It is not improbable that the tax system was operated with built-in assumptions about acceptable levels of arrears and that provincial officials were perhaps only required to take action if revenue fell far short of the notional target or their overall provincial target was not reached. Aristocles seems to have been congratulated for his nearly 84 percent return by the provincial governor and his legate and by his fellow townsfolk.

The total tributum yielded by individual provinces no doubt varied greatly, but we should envisage that the expected returns were probably firmer target figures, as ultimately the imperial budget depended on these sums. Rogue emperors could blow holes in their own budgets through extravagance—at least this was part of the standard diagnosis of the “bad emperor.” So Caligula, we are told, spent 10 million sesterces, “the tribute of three provinces,” on a single banquet.52 These must have been small provinces as the average sum required of provinces in the mid-first century ought to have been closer to 20 million sesterces. Although the Hopkins model envisages net flow of tax income from the core Mediterranean provinces to those with large military garrisons (and thus high costs), it is also entirely plausible that frontier provinces were squeezed harder to meet financial targets. If so, that has major implications for the observed pattern of economic development in provinces such as Britain.53 Conversely more easily achievable targets in core provinces could have allowed officials on the spot considerable discretion on what sort of arrears were acceptable from different communities under their purview—providing ample scope for corruption one suspects.

The ability of some emperors exceptionally to write off arrears (and have the records of those tax debts publicly burned to reassure provincials) is testimony to the fact that for long periods, notwithstanding a shortfall on individual assessments, the empire raised more than the minimum sums required to meet its core costs. It is arguable, however, that the large army pay rises initiated by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in relatively quick succession did mark a turning point of sorts—in Duncan-Jones’s figures this represents a near doubling of the military budget in the space of a decade.54

While today we tend to discriminate between direct and indirect taxes, in Roman times the main difference was in terms of regularly levied taxes such as the poll tax (tributum capitis) or the land tax (tributum soli) and irregular liability for tax on sales or manumission of slaves, on inheritance, and so on.55 The 5 percent inheritance tax came to be of particular importance as it underwrote the retirement fund for the army. It was levied only on Roman citizens, whose numbers grew steadily in the provinces in the first two centuries AD and then exponentially so with the massive extension of citizenship by Caracalla in 212. As in many other areas of bureaucracy there is evidence of an increase in direct supervision of various taxes over time—accounting in part, at least, for the huge growth in the procuratorial service from 23 people under Augustus to 182 posts by the mid-third century.56 It is plausible that imperial officials with financial responsibilities had performance targets to meet and when a shortfall occurred might even have had discretion to make an additional tax levy, as the praetorian prefect Florentinus evidently proposed for Gaul in AD 357.57

Taxation and other revenue raising by the state was (unsurprisingly) unpopular and complaints about it were common. However, there is a general assumption in many books that the rates of taxation were low in comparison to modern times.58 There are several reasons to believe this may not be entirely accurate. Recurrent taxation, such as the land tax, may have been 25 percent of grain production in Egypt (and there was a plethora of additional taxes in Egypt).59 Although views vary on the extent of change to preexisting Ptolemaic landholding and tax systems under Rome, it is generally agreed that Egypt was effectively exploited for the benefit of both the Roman state and the uppermost tier of local landholders.60

The highest tribute rates may have applied to peoples that Rome wanted to make an example of or whose lands happened to be occupied by large garrisons. The taxes we generally hear about in the sources were those that were most resented by the Roman elite, close to the center of power. The 5 percent inheritance tax on Roman citizens—introduced by Augustus specifically to fund the discharge bonuses of the army—had a particularly large impact on the wealth in land and capital of the Italian elite and was a crucial exception to the general avoidance of putting a financial burden on the imperial elite.61 At the very least, this might suggest that the fiscal burdens imposed on subjects were heavier than is sometimes assumed, though the mixture of regular and irregular deductions must have made it hard for people to work out their overall burden. The expressive list of epithets for tax men contained in a second-century AD source gives a good flavor of public opinion about their work: “Should you wish to abuse a tax farmer, you might try saying: burden, pack-animal, garotter, sneak-thief, shark, hurricane, oppressor of the down-trodden, inhuman, nail in my coffin, insatiable, immoderate, Shylock, violator, strangler, crusher, highwayman, strip-jack-naked, snatcher, thief, overcharger, reckless, shameless, unblushing, pain in the neck, savage, wild, inhospitable, brute, dead weight, obstacle, heart of stone, flotsam, pariah, and all other vile terms you can find to apply to someone’s character.”62 We might also note the observation in Cassiodorus that sailors feared customs officials more than storms.63

As noted already, the actual rates of tributum imposed on provincial peoples reflected a settlement between them and the state based on their perceived merits. Siculus Flaccus summed up the situation well:“Certain peoples, with pertinacity, have waged war against the Romans, others having once experienced Roman military valour, have kept the peace, others who had encountered Rome’s good faith and justice, declared their submission to the Romans and frequently took up arms against their enemies. This is why each people has received a legal settlement according to merit: it would not have been just if those who had so frequently broken the peace and had committed perjury and taken the initiative in making war, were seen to be offered the guarantees as loyal peoples.”64

It is certainly plausible that these impositions could have been quite punitive on occasion. The ancient sources contain several explicit references to revolts being sparked by the nature of tribute exactions. For example, Dio on the Pannonian revolt in AD 6 noted the Illyrian view that it was Rome that was responsible, “for you send as guardians of your flocks not dogs or shepherds, but wolves.”65 A major grievance underlying the widespread uptake of the Boudican revolt in AD 60–61 evidently concerned taxation.66 In the reign of Domitian, the Nasamones of Syrtica revolted against the imposition of tribute, “exacted from them by force.”67 Similarly, in the reign of Tiberius a reinterpretation of the tribute levied in ox hides on the Frisians lying to the north of the Rhine River’s mouth by the centurion in charge of this region led to severe hardship followed by revolt.68 There was a careful balance to be struck between the precise level of tribute exacted and the ability of local communities to pay. Punitive levels of tribute imposed by Rome carried the risk of armed resistance. The examples cited above are a selection from a number of cases where things went wrong. Perhaps more surprising is how often the Romans managed to get the balance right.

The exact detail of Roman censuses, taxation, and tribute exactions will always be elusive because of the nonstandardization of Roman practices across the empire. It is simply not possible to model the picture in Britain in comparison with what we see in Egypt. However, the snippets of extant primary documentation relating to landholding, land management, census activity, and tax collection should encourage us to envisage a series of provincial systems that were based on systematic data gathering and rational accounting principles.69 The bottom line was the bottom line. Through a variety of methods it appears that the Principate was able to meet its budgetary needs most of the time. If we take 800 million sesterces as the average annual income figure for the first two centuries AD, that represents an aggregate tax take of 160 billion sesterces.

ROMAN ECONOMIES

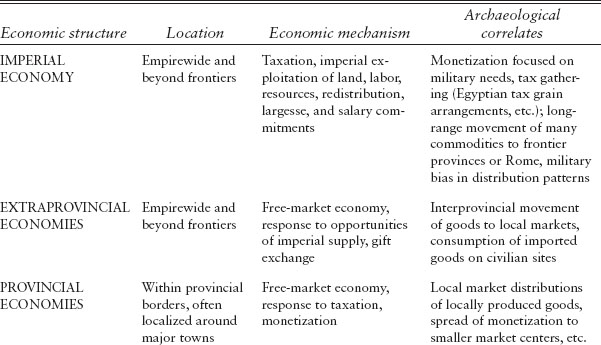

In this section I shall argue for the existence of three distinct economic entities in the Roman world: an imperial economy, an interconnecting series of extraprovincial economies, and a series of regionally centered provincial economies (see table 5.2). I shall explain each of these in turn in simple terms and then consider how they may have operated in harness with each other.

The raising of the revenues needed to pay for the costs of running the empire were one part of what we might define as the imperial economy.70 The other element of this concerned the economic structures set in place over time to transport and deliver needed resources to Rome and to the key functionaries of imperial rule—the armies and administrators in the provinces.71 The imperial economy thus concerned the revenues and disbursements of the state, incorporating the army and infrastructures of governance, the taxation system, the exploitation of resources and the supply issues relating to the needs of the state. A huge amount of economic activity is covered under this heading, though only occasionally can it be unambiguously identified from the archaeological evidence.

Different Roman economies?

The imperial economy intersected with extraprovincial economies, whereby interregional movement of goods took place across customs zones at provincial boundaries. Archaeological evidence is now clear-cut on this point: there was a huge expansion in the scale and nature of interregional movement of goods (including agricultural staples), only part of which can be attributed to the imperial economy.72 It can be difficult to differentiate between the mechanisms from the archaeological assemblages alone, but in Roman times the extraprovincial commercial trade should have been easily distinguishable from the imperial economy. The fact that there were specific exemptions from the customs dues (portoria) for goods carried under state contracts—for instance, for military supply—demonstrates that officials on the ground could in principle differentiate between the operation of imperial and extraprovincial economies. The former area was governed by paperwork—contracts, orders, and so on—as is clear from a number of detailed customs tariffs for example.73 Of course, there was considerable scope for fraud and tax evasion in the movement of goods and the blurring of the distinctions between different categories of cargo would have been to the advantage of the merchants and shippers involved.74

I suggest that provincial economies relate to the emergence or further evolution of local market systems and networks, increased rural productivity, and manufacturing activity—even where these were in part at least a response to the pressures/demands of the imperial economy. The provincial economy also integrated aspects of pre-Roman economic structures, in northern Europe often involving practices embedded in social customs.

To conceptualize the Roman economy in this way is, of course, to disaggregate elements that were not always clearly divisible in practice and which were in many respects interdependent. Like a complex financial spreadsheet, changes to one of these economic areas would have generated automatic adjustments in other areas as well.

What I think my model achieves is a clearer appreciation of how it was that the Roman economy could appear both so modern and so primitive at the same time, why scholars can recognize both formalist and substantivist elements, and how it was capable of generating both globalized and highly localized distributions of material culture. Above all, it focuses attention on the extent to which Rome’s financial needs acted as a driver of economic development and monetization in the provinces. A corollary of ruling regions was that the Roman state needed to capitalize on the possibilities for the exploitation of resources (natural, human, and in terms of farmed and manufactured products). The operation of the imperial economy might have had particularly large effects at certain times and places.

There were five key drivers in the imperial economy: the census, land, tax/tribute, resources, and supply systems. Each of these had large effects on the evolution of provincial and extraprovincial economies (summarized in Table 5.3). We can visualize these as links in a chain: knowledge– resource allocation–resource collection–resource exploitation–resource distribution. The overall aims were to assess and mobilize the economic potential of the empire and to collect and deliver the resources needed for the maintenance of the empire and the well-being of its key constituents. The imperial economy evolved and changed markedly over time, but the key proposition here is that at its peak it operated on a scale and at a level of sophistication that differentiates it from the vast majority of other ancient states.

The “road map” for the imperial economy was the census, working on the principle that knowledge equals power. As a vital fact-finding procedure that was coordinated by financial officials (and the army in frontier areas) the census underlay the exploitation of every province.75 It established the extent and value of provincial lands and the size of regional populations. These data enabled the state to set down figures for tax/tribute assessment, compulsory army recruitment, labor and other services (corvées, liturgies) to be rendered. Records were held centrally within provinces (and arguably in summary form, at least, at Rome; there were periodic revisions and adjustments to population figures, information on land productivity, and so on. There is no doubt that the census was far from perfect or infallible in representing the regional resources of the empire, but by premodern standards it must have been an extraordinarily useful instrument of imperial government, providing an empirewide basis for the effective exploitation of land, resources and people

LAND

Land was routinely “confiscated” from defeated enemies and accrued to the territory of Rome. Rome is often praised for the extent to which it subsequently returned control/ownership of such land to its previous owners, but it is clear that this was very often conditional on the terms of their surrender and their continuing good behavior. Put bluntly, loyal subjects were rewarded with generous land settlements, while those who resisted more fiercely or broke treaties were liable to be subjected to far less favorable settlements. Some of the land that was seized from defeated enemies was reallocated to colonists—often army veterans; some land was sold, some land became state land (ager publicus) or imperial estates for rental (a portfolio that grew over time). The nature and sophistication of Rome’s arrangements relating to conquered land changed significantly in the last centuries BC, developing from a complex series of ad hoc measures in the early stages of Roman expansionism into a fully imperial system of exploitation at a comparatively late date.76 Land was thus a significant lever to encourage the compliance of subject peoples and communities. Conventional studies of the Roman countryside emphasize the supposedly ubiquitous and irresistible rise of the villa estate in place of indigenous homesteads and farms,77 but the reality appears a good deal more complex, with some regions undergoing significant change and economic growth and others entering prolonged periods of material and social stasis.

| CENSUS (KNOWLEDGE) | •The census was a vital fact-finding procedure that underlay the exploitation of the provinces. Coordinated by financial officials (and the army in frontier areas), it established the extent and value of provincial lands, size of population, etc., and set down markers for tax/tribute assessment, compulsory army recruitment, labor, and other services (corvees, liturgies) to be rendered, etc. |

| •Periodically revised and records held centrally. | |

| •Census is crucial in providing solid basis for exploitation of land, resources, and people. | |

| •Knowledge = power. | |

| •Land was routinely confiscated from defeated enemies—the extent to which it was returned to previous owners very often conditional on terms of surrender and subsequent good behavior. | |

| •Loyal subjects rewarded with control of land. | |

| •Some land reallocated to colonists—often army veterans, some land sold, some land became state land (ager publicus) or imperial estates (growing over time). | |

| LAND (RESOURCE ALOCATION) | •Land was thus a significant lever to encourage compliance. |

| •Land sometimes surveyed, divided, and reallocated (centuriation). | |

| •Land was also subject to rules (especially imperial estates). | |

| Tax/tribute (resource colection) | •Taxation/tribute levied from neighbors and conquered peoples. No standard package, varied from case to case and many exemptions and special dispensations for communities seen as deserving. |

| •Taxation could be based on land or on capitation. Customs dues and market taxes on movement/sale of goods, inheritance tax on wealth. | |

| •Taxes collected by: tax farmers (publicani), local civic authorities, imperial officials—variable practice. | |

| •Tax collection not always efficient—periodic remissions of tax arrears (HS900 million under Hadrian), but note that the rich were more successful in deferring tax payments and benefiting from remissions. | |

| •In general, tax probably quite burdensome for poor, and some provinces and regions harder hit than others—explains some of visible differences in wealth accretion. | |

| NATURAL RESOURCES (RESOURCE EXPLOITATION) | •Natural resources were often exploited by Rome—gold, silver, copper, even iron mines; marbles and other decorative stones; salt; cedars of Lebanon; etc. |

| •Rise in scale of mining activity in first and secong centuries AD—especially for production of gold and silver coinage. | |

| •Much in imperial or state ownership, though some subcontracted. | |

| SUPLY (RESOURCE DISTRIBUTION) | •Supplying the system involved Rome and the armies. |

| •Economic impact of the empire went beyond moving specie to pay troops—major infrastructure for supplying food and other necessities to city of Rome and the frontier armies. | |

| •Population of city of Rome: c. 1 million. | |

| •Total size of army: c. 0.5 million. | |

| •Huge undertaking—fulfilled mostly by private shippers and traders working with state supply contracts. | |

| •Bureaucracy evolved over time, especially from time of Augustus onward. Praefectus annona in overall charge of supply system. | |

| •Imposes measure of price control and price fixing. |

Certain land was surveyed, divided, and reallocated in the process we know as centuriation.78 This was often linked to the census process as a means of evaluating a region’s worth and productive capacity. Land was also often subject to complex legal rules (especially imperial estates).79

TAX

As has already been described, taxation/tribute was levied from neighbors and conquered peoples alike. There was no standard package to be applied across the empire; the tax settlement varied from case to case and there were many exemptions and special dispensations for communities seen as deserving. Taxation was fundamentally based on land or on capitation, but there were many additional taxes that we should take account of. Customs dues and market taxes related to the movement/sale of goods, while inheritance tax was imposed on the property of Roman citizens.80 Taxes were collected by diverse means, often building on earlier local practices. In the Late Republic greater use was made of tax farmers (publicani), but under the principate the task was increasingly taken up by local civic authorities supported and cajoled by dedicated imperial financial officials.

Tax collection was certainly not always efficient, and it has often been noted that tax arrears built up recurrently in many provinces. The periodic remissions of these tax arrears (900 million sesterces under Hadrian), were more likely to benefit the rich who were probably more successful in deferring tax payments. In general, taxes were probably quite burdensome on the poor and some provinces and regions were harder hit than others. This may explain some of the visible differences in wealth accretion across the empire.

Natural resources were often exploited by Rome; there were imperial gold, silver/lead, copper, and even iron mines; quarries for marbles and other decorative stones: saltworks and brine springs; and even the cedars of Lebanon were decreed an imperial resource.81 The archaeological evidence suggests a substantial increase in the scale of mining activity in the first and second centuries AD, especially linked to the production of gold and silver coinage. Certain resources were placed under direct imperial control, while others were exploited by means of subcontracts with individuals or companies (socii) who shared the capital expense and risk. The overriding requirements of the state to exploit some key regional resources had a major impact on the socioeconomic evolution of communities living close to the resources. In northwest Spain, for instance, it is clear that the hundreds of Roman gold mines now known could not have been worked without significant labor inputs from the local people. In other words, Rome often mobilized the human resources of regions rich in natural resources to facilitate and bring down the direct cost of the exploitation of those resources.82

SUPPLY SYSTEMS

The Roman Empire was an unusually well-connected world by the standards of preindustrial ages.83 The economic impact of the empire went far beyond moving specie to pay troops. The Roman state moved raw material, agricultural staples, and manufactured goods on an unprecedented scale across large distances.84 “Supplying the system” involved mechanisms for the provisioning of the city of Rome and the armies.85 Over time a major infrastructure was created for satisfying the vast consumption needs of Rome (with a population of about one million) and the frontier armies (about half a million men). This was a huge undertaking for a preindustrial state—another area where we find the best comparisons among other imperial powers rather than the normative preindustrial states. This was fulfilled to a large extent by private shippers and traders working with state supply contracts.86 The bureaucracy evolved over time, especially from Augustus onward, and a high equestrian post—the praefectus annona—was created. The existence of the annona and the supply mechanisms that went with it created conditions in which by accident or design there was a measure of price control and price fixing.

DISCREPANT ECONOMIES

The broad spectrum of socioeconomic structures and practices that made up what we term the Roman economy ensured that individual experience of it was extremely varied. As a Talmudic source has put it, “The [Roman] government gives abundantly, and takes away abundantly.”87

This variation was conditioned partly by social factors (as noted already, wealthy people were often better at evading full payment of their liabilities), partly by geographical differences, and partly by historical and institutional differences. Where suitable structures of taxation already existed in pre-Roman societies, these were often adopted as a basic starting point for Roman exactions. It was comparatively rare for Rome to introduce universal measures of taxation and the patterns in most provinces reflected the gradual accretion of regionally focused impositions. Individuals and communities faced both opportunities and challenges from Rome’s exploitation of empire with varying levels of financial success. An economic theme I have been attempting to understand for a number of years concerns the extent to which Roman provinces appear to have been landscapes of opportunity or resistance.88 I hope to have shown how the unequal impact of the imperial economy provided new and unheralded scope for wealth creation in some areas, while at the same time denying opportunity in others because of the relative scale of exactions of regional surpluses. The diverse patterns of economic behavior that we can recognize in the archaeological record represent in part at least the emergence of distinctive economic identities. As with social identities, our understanding of the individual choices that contributed to the formation of different economic identities needs to recognize that these were often responding to a fundamental colonial discourse.

Early versions of this chapter were presented at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference in Cambridge in March 2006 and for the Miriam S. Balmuth Lectures in Ancient History and Archaeology series at Tufts Universty. I am grateful to several members of both audiences for constructive comments.

1 See, for example, Finley 1985, 33–34, 58–59, 78; Rostovtzeff 1957. For more recent debate on the primitivist/modernist divide, see, among others, Andreau 2002; Bang 1997; Drinkwater 2001; Garnsey and Whittaker 1998; Jongman 2002; Meikle 2002; and Saller 2002.

2 Polanyi,Arensberg, and Pearson 1957.

3 See, for example, Peacock and Williams 1986, 55–63.

4 Such challenges come in Horden and Purcell, 2000, 146–47, 150–51, 606. See also various papers in Harris 2005.

5 Harris 1993b, 2000; Hitchner 1993, 2005; Hopkins 1980, 1996; Horden and Purcell 2000, esp. 143–52, 342–77; Mattingly 1996a, 2006b; Temin 2001; Wilson 2002, 2006.

6 Mattingly and Salmon 2001b, 8–11.

7 Pleket 1993a, 317. Cf. the conclusion of Rathbone 2003b, 227: “Financing of marine commerce in the Roman world in the first two centuries AD cannot easily be constrained within the primitivist model of the ancient economy.”

8 Bang 2006; De Ligt 1993; Giardina 1986; Temin 2001.

9 Toutain 1930, 253.

10 See Garnsey and Saller 1987, 43: “The Roman economy was underdeveloped. This means essentially that the mass of the population lived at or near subsistence level. In a typical underdeveloped, pre-industrial economy, a large proportion of the labour force is employed in agriculture. … The level of investment in manufacturing industries is low….

Backward technology is a further barier to increased productivity.”

11 Hopkins 1980.

12 See Duncan-Jones 1992, 1994.

13 Hopkins 1996 essentially updates and supplements the 1980 article and attempts to answer the critics.

14 See Geraghty 2007 on globalization and the Roman economy.

15 Temin 2001, 181.

16 Woolf 1992a.

17 See, for example, Lo Cascio 2006, 2007; Kehoe 2007.

18 See for example, Alpers 1995, on the fiscus; and Cottier et al. 2009 on tax law in Asia Minor.

19 Millett 1995a, 12.

20 Given 2004, 49–50.

21 Barrett 1989; See Bang 2002, 2006 for reflections on the nature of the economic structures of tributary empires, comparing Rome and the Mughal Empire.

22 Germain 1955, 19–29.

23 Sibylline Oracles, 3.179, 3.189; cf. Ecclesiastes Rabbah, 1.7.

24 See chapter 1 of the present volume.

25 This is contra Love 1991, 272–74, which seems to argue that economic competition between the princeps and the patrician elite was a main driver behind the creation of the economic systems of the principate.

26 Following the model set by Augustus, see Suetonius, Augustus, 101.4; Tacitus, Annals,

1.11.

27 Polybius, Histories, 3.27; 21.43.19; Plutarch, Pompey, 45.3.

28 For other ancient evidence, see Frank 1933, 1:127–38.

29 Fulford 1992.

30 Given 2004.

31 Ibid., 93. There are echoes here of the views expressed by Barrett 1997. It is true, of course, that nonimperial regimes also exact taxation and labour, but the “paper trail” efficiency and the sometimes long-range nature of imperial impositions/exactions often give them a special character.

32 This theme is developed in Jones 2006 as a “Roman predicament facing the United States today.

33 See Johnson 2006 for the “lax tax” view; on Hadrian’s generosity with tax arrears, see Duncan-Jones 1994, 59–63; Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, 309; Dio, Roman History,

69.8.1.

34 Goldsmith 1987, 34–59, provides an overview of the Roman financial system, but the value of the book lies in its comparative framework of a number of preindustrial economies.

35 Aarts 2005; Duncan-Jones 1994, 95–247; Howgego 1992, 1994.

36 Adams 2001, 2007; Carreras Montfort 2002; Kolb 2002.

37 Fentress 2006.

38 Tilly 1990, 79.

39 See for instance, Duncan-Jones 1994, 33–46 (on which table 5.1 is largely based); see also the important discussion in Mattern 1999, 123–61, and the more speculative figures in Goldsmith 1987, 34–59.

40 See Duncan-Jones 1994, 33–37, for the detailed arguments. See also Mattern 1999, 130, n. 27.

41 Tilly 1990, 84–91.

42 Tacitus, Histories, 4.74.

43 Dio, Roman History, 73[74].5.4.

44 Mattern 1999, 136.

45 Duncan-Jones 1992, 187–210; 1994, 47–63; Lintott 1993, 70–96; Nicolet 1976, 1988, 2000.

46 See Capponi 2005, 123–55, for an up-to-date summary.

47 This is summarized in Roth 2002, 382.

48 Cicero, Letters to His Brother Quintus, 1.1.34.

49 Galsterer 2000, 353.

50 Inscriptiones Graecae 5.1.1432f; translation in Levick 1985, 75–85, no. 70.

51 Nicolet 1991.

52 Statius, Silvae, 10.4.

53 On the economy of Britain, see Fulford 2004; and Mattingly 2006c, 491–520.

54 Cf. Duncan-Jones 1994, 33–35.

55 Eck 2000b, 282.

56 Eck 2000a; 2000b, 284–87; cf. Shipley et al. 2006, s.v. “equestrians.”

57 Ammianus Marcellinus, Histories, 18.3.

58 Mattern 1999, 132, n 35.

59 Duncan-Jones 1994, 54–55.

60 Bagnall 2005; Rathbone 2002.

61 Mattern 1999, 126, 132–33.

62 Pollux, Onomasticon, 9.30–31.

63 Cassiodorus, Variae, 4.19.

64 Siculus Flaccus, De condicionibus agrorum, 7–8.

65 Dio, Roman History, 56.16.3.

66 Ibid., 62.3.3.

67 Ibid., 67.4.6.

68 Tacitus, Annals, 4.72.

69 Ørsted 1985; Peña 1998; Rathbone 1991.

70 See also Harris 2007 and Lo Cascio 2007 for the evolution from Late Republic to Early Principate.

71 For the supply of Rome, see Aldrete and Mattingly 1999; Garnsey 1988; Morley 1996; Pleket 1993b; and Sirks 1991, 2007. For the armies, see Erdkamp 2002; and Papi 2007.

72 Bonifay 2004; Greene 1986; Mattingly 1988a, 1996a; Panella and Tchernia 2002; Parker 1992.

73 Horden and Purcell 2000, 354–56.

74 Whittaker 1994, 110–13.

75 Nicolet 1988, 2000; cf. Capponi 2005, 83–96 (on Egypt). For the significance (and sophistication) of census records in the administration of the Ottoman Empire, see Given 2004; and Zarinebaf et al. 2005.

76 Rathbone 2003a.

77 Dark and Dark 1997; cf. Bayard and Collart 1996.

78 Campbell 2000; Dilke 1971.

79 Kehoe 1988, 2007.

80 Inheritance tax was closely linked to the military budget, being set up under Augustus to fund the discharge packages for time-expired soldiers. The extension of citizenship by Caracalla increased those liable to inheritance tax by many millions, at a time when army pay had increased dramatically.

81 Wilson 2007.

83 Adams 2007; Adams and Laurence 2001; Horden and Purcell 2000; Morley 2007; Purcell 2005a; Purcell and Horden 2005.

84 This is perfectly exemplified by the physical structures of the port of Rome; see Keay et al. 2005.

85 Aldrete and Mattingly 1999; Funari 2002; Papi 2007; Stallibrass and Thomas 2008; Whittaker 2002.

86 Sirks 1991, 2007.

87 Midrash Sifre de Bei Rab (Deuteronomy) 354.

88 Mattingly 1997c, reprinted in the present volume as chapter 6.