Metals and Metalla

ROMAN COPPER-MINING LANDSCAPE IN THE WADI FAYNAN, JORDAN

MINING AND METAL PRODUCTION IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The prospect of increasing state revenues may not have been the prime motor of imperial expansion, but the Roman state and its ruling order became adept at exploiting the opportunities that conquest and domination afforded them. Indeed, this was a necessity for the maintenance and prolongation of the empire. Just sustaining an army of 500,000 men should have been challenge enough; but the Roman Empire was extraordinarily profligate in other ways.1 Conspicuous consumption at the center ran at a terrifying level (whether on the imperial court, on the building schemes of emperors, or on luxuries and status symbols in elite society). This was an empire whose elite class allegedly spent up to 100 million sesterces on the annual trade for eastern exotics.2 It is no wonder that Rome was known as Daqin in fourth-century China—literally, “treasure country.”3 A particular problem with this sector of the extraprovincial economy was that it was extra-empire, too, and took wealth beyond the range of state taxation. How did the Roman Empire make good the loss of specie beyond its borders? One measure, of course, was to tax the Eastern import trade more highly than other interregional trade (25 percent instead of 5 percent). However, that still left a substantial potential trade gap, represented by a large net outflow of gold and silver coinage.

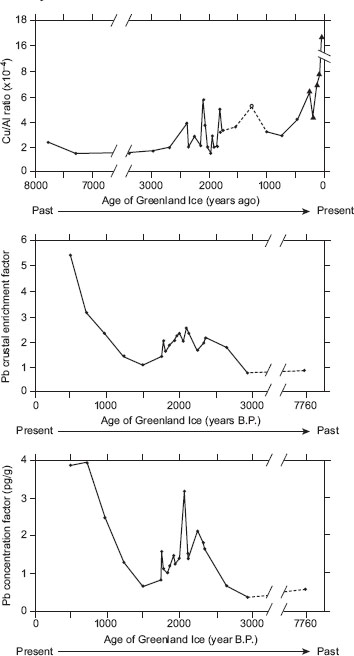

Mining and metallurgy were key operations used by Rome to plug this gap. The scale of Roman mining activity is demonstrated by the emerging picture of global pollution registered in the Greenland ice cores (see fig. 7.1).4 Analysis of the ice cores has revealed that fresh layers of ice are formed each year and that by counting back, the ice can be accurately dated, much as tree rings. The chemical analysis of ice across time has now shown that the major pre–Industrial Revolution peak in hemispheric pollution occurred in the Roman period, with notable peaks in both copper and lead.5

FIGURE 7.1 Summary charts of the Greenland ice-core data on hemispheric copper and lead pollution levels, showing significant peaks in the Roman era. (Redrawn from Hong et al. 1994.)

FIGURE 7.2 The largest of several hundred known Spanish gold mines; the main opencast mine at Las Medulas is 2–2.5 kilometers across.

The evidence of mining and quarrying in the Roman world is cumulatively impressive, but difficult to evaluate in quantifiable ways.6 It is clear from analysis of literary and epigraphic data that Rome did not have a single centralized bureau for the management of mines and quarries but a range of provincial posts was created over time to deal with particular local circumstances. There were inevitably some strong similarities in regional practice, but no overall blueprint.7

Literary and archaeological evidence for the scale of mining fills out the picture. We are told that the mines in Spain yielded 36 million sesterces annually in the second century BC.8 By the first century AD, the substantial gold fields of northwest Spain were contributing 20,000 pounds (over 6 metric tons) of gold a year, the equivalent of about 85 million sesterces.9 The Las Medulas mining complex was the largest of more than 230 gold mining sites in northwestern Spain, and its scale illustrates the human dimension of this activity (see fig. 7.2).10 The main opencast mine here was about 2–2.5 kilometers across and more than 100 meters deep—almost certainly the largest preindustrial, constructed hole on the planet. The deposits of gangue and other mine waste were spread across 5.7 square kilometers around the 5.39 square kilometers of opencast mines. The extraction of over 93.5 million cubic meters of the landscape here was assisted by impressive hydraulic technology, with mountain-ridge aqueducts traversing over 100 kilometers of incredibly difficult terrain to reach the vast header tanks at the top of the Las Medulas mine.11

However, the large scale and sophisticated technologies of early imperial mining operations masks a paradox. One of the great anomalies of the Roman economy is the fact that many of the Spanish mines went out of production or declined markedly in scale by the later second century AD.12 The same is also true of mining activity in many other provinces—initial large activity that was not sustained on the same scale into later antiquity.

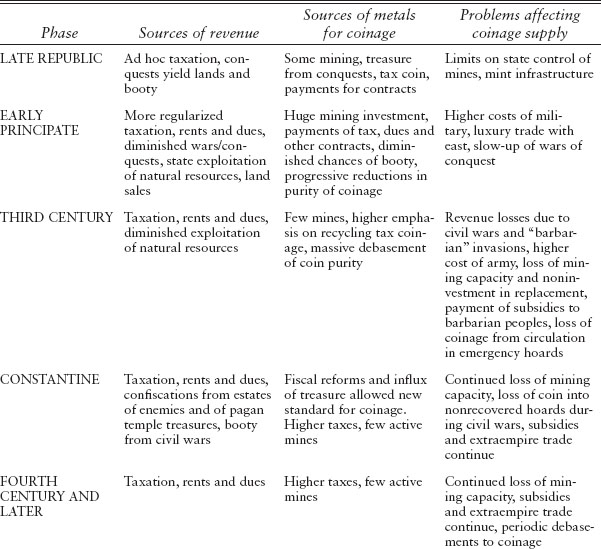

Table 7.1 illustrates some of the potential changes in the fiscal policies of the empire from the Late Republican era until the late fifth century AD. A key question that arises here concerns why an imperial power would tolerate a massive reduction over time in its capacity to make good through mining a recurrent shortfall in the availability of metal for coinage. Yet that is what seems to have occurred in the Roman Empire. From a peak in the first and second centuries AD, Roman mining productivity appears to have declined significantly thereafter, a position exacerbated by the loss of the Dacian gold mines in the late third century.13 This does not mean that the empire no longer had need for generating reserves of precious metals, and mining certainly continued at a large scale in some regions (as the Faynan case study below illustrates). However, it seems clear on current evidence that the mining output of the late Roman Empire was considerably less than that of the High Empire. The idea that the most abundant and accessible deposits were becoming worked out can only be partly true—the medieval and early modern miners in Europe, for instance, successfully revisited many of the same deposits with essentially similar technology.14 What this suggests is that the later Roman Empire put greater emphasis on other methods of securing the supply of coinage needed for the imperial budget.

Revenue streams, availability of metals and coinage

We need to distinguish here between apparent cycles of economic decline and the application of different strategies to the problem of producing/raising specie. In the Early Principate the solution was to embark on remarkable, but costly, mining operations; in later Roman times the emphasis had shifted somewhat to the alternatives of exacting higher levels of tax, debasing the purity of the coinage and translating part of the cost of the army into payments in kind. Taxation in kind also became more significant in some regions. Prospecting and developing mineral resources was expensive and not necessarily productive in full proportion to the effort expended. Costs tended to rise over time because mining worked out the most accessible deposits, necessitating deeper and more dangerous galleries. Fundamentally, then, the scaling down of mining activity does not indicate a collapse of Rome’s attempts to exploit resources; rather, this represents a refocusing of attention onto other forms of exploitation and other resources. This is surely reflected more generally by the increased evidence for state intervention in economic activity from the time of Diocletian onward, as indicated by maximum price edicts, staterun workshops for army supply, enforcing hereditary occupations, and so on.15 The empire may also have attempted to make up some of the shortfall in precious metals by importing gold from West Africa via the Saharan trade routes.16

MINING AND THE COLONIAL BODY

Study of the mining regions also illuminates the human dimension of the Roman Empire’s exploitation of resources. Even with water to assist with the moving and washing of ore-bearing deposits at Las Medulas, that mine must have involved the labor of a huge number of people in scenes that can best be imagined from the photographs by Sebastião Salgado of the Brazilian gold mine of the Serra Palada—a modern relic of preindustrial labor conditions (see fig. 7.3).17 How was this labor mobilized and paid for? The common assumption is that such mines involved a combination of salaried free labor and forced labor, particularly in the form of criminals condemned to the metalla for serious offenses. However, other forms of labor exploitation are also to be expected in Roman mining districts. Some degree of forced labor may have been more generally imposed as munera (required duties) on whole communities. In some of the main mining areas of the empire it is likely that the provision of labor was an obligation imposed by Roman peace settlements with local peoples—especially as in northwestern Iberia where armed resistance had been protracted. Studies of the settlement pattern around the northern Spanish mines suggest a significant level of reorganization of local communities to support the mining activity—a point now backed up by the discovery of an edict of Augustus from El Bierzo.18 This document details the favorable treatment of one small community (the Castellani Paemeiobrigenses of the Susari) who had not joined a rebellion against Rome. The clear implication is that other communities were harshly penalized and that Rome’s exploitation of this region involved not only natural resources but human labor as well.19

FIGURE 7.3 A glimpse of preindustrial labor conditions? Brazilian gold mine at Serra Palada. (Photograph © Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images).

Roman mines and quarries provide evidence of other forms of violence to the body. The metalla attained the direst repute through the writings of Christian accounts of martyrdoms, but they operated across longer time frames and against a broader range of people deemed socially unfit. The committal of people for extreme punishment was clearly designed to be exemplary and in addition to the customary floggings inflicted on people before they were even sent to the metalla, there were additional indignities such as being shackled, having marks tattooed or branded on the forehead, the head being half-shaved. In extreme cases people were emasculated, blinded in one eye, or maimed in one leg.20

However, the ugliness of imperial exploitation of people in such places went beyond visible marks on the bodies of slave workers or the mass imposition of some degree of forced labor on communities. The hundreds of imperial mines in Spain and elsewhere must also have relied heavily on free labor, in much the same way that gold and diamond mines in southern Africa lure workers with promises of higher than average wages, but at the cost of drastically shortened life-expectancy. The deliberate, accidental, and incidental side effects of Rome’s exploitation of resources all had a sociopolitical as well as an economic dimension. They serve to illustrate the way in which subject people experienced the imperial economy in a physical way.

INTRODUCTION TO THE WADI FAYNAN

The rest of this chapter will present a single case study of a Roman imperial mining operation (metalla) as an example of the potential environmental and human consequences of large-scale Roman metal production. As such, it stands for many instances of Rome’s exploitation of the key natural resources of provincial territories. Tacitus, for instance, was explicit in describing the mineral resources of Britain as the “spoils of victory.”21 However, as we shall see, the consequences of Rome’s pursuit of economic gain carried a high human and environmental cost. Here I draw on the results of the Wadi Faynan landscape survey (1996–2000). Directed by Graeme Barker, David Gilbertson, and myself, this project was an interdisciplinary and diachronic investigation of evidence of environmental and climatic change, settlement pattern, and human activity.22

FIGURE 7.4 Map of Jordan showing mineral resources and location of Wadi Faynan, ancient Phaino. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

FIGURE 7.5 Overall plan of Khirbat Faynan, ancient Phaino, showing main structures and slag heaps. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

The sedimentary copper ores of southern Jordan represent one of the rare abundant copper sources in the Levant and have through many phases of prehistory and history been a key resource at the regional scale (see fig. 7.4). Copper mining on both sides of the rift valley south of the Dead Sea has a long history, with Beno Rothenberg’s studies at Timna on the west side being particularly well known. But as recent work of the Deutches Bergbau-Museum has shown, the evidence from the eastern side of the Wadi Araba is, if anything, even more impressive.23 Copper sources there have been exploited since the seventh millennium BC, with early peaks of activity in the Early Bronze Age and Iron Age. It is also clear that the Roman phase of exploitation was on a very significant scale. In the Roman phase, large tap furnaces were the norm, with separation of slag and metal within the furnace and the tapping process producing large plates of distinctive vitreous slags.

The total volume of slag at sites in the Wadi Faynan region far exceeds the quantities reported by Rothenberg for Timna or recorded at the lesser Jordanian sites in Wadi Abu Kusheiba.24 Andreas Hauptman and his collabrators have estimated that the slag heaps at the four largest Iron Age production sites contain a total of over 100,000 metric tons of slag, representing perhaps 6,500–13,000 metric tons of copper. Although there appears to have been a decline in production in the late Iron Age and early Nabataean period, there is some evidence to suggest continuing or reviving mining activity under the Nabataean kingdom.25 Roman interest in annexing the Nabataean kingdom under Trajan may have been influenced by knowledge of the copper resources. In the Roman period, the smelting of copper is thought to have been particularly concentrated at the site of Khirbat Faynan (ancient Phaino), where Hauptman estimates that about 40,000–70,000 metric tons of slag and 2,500–7,000 metric tons of Roman copper were produced (see fig. 7.5).26 It appears that ore was brought into the smelters at Khirbat Faynan from quite a large region and not simply from the nearest cluster of mines, located a few kilometers to the north.

FIGURE 7.6 (a) and (b) The Wadi Faynan in Roman and Byzantine times, showing the location of the mines, the mining control site (Khirbat Ratiye WF1415), the smelting and administrative center (Khirbat Faynan WF1) and the field system (WF4). (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007).

Phaino was set back from the main Roman road up the Wadi Araba, linking the Red Sea port of Aqaba (Ailat) and the Dead Sea (see fig. 7.4). It was the terminus of an eastward spur of the route that ran across the Negev connecting the Mediterranean port of Giza with the Wadi Araba road. The mining center sat just at the mountain front, where tracks ascend to the Jordanian plateau, on top of which ran the major eastern frontier roads and the routes connecting Petra with the trans-Jordanian cities.27 The site was thus both isolated, but tied into Roman communications networks. As this region comprised a pre-desert environment in Roman times (as today), the location presented considerable challenges for maintaining and supplying a substantial mining and smelting workforce.

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE MINING LANDSCAPE

The Wadi Faynan survey concentrated on an area of just over 30 square kilometers of landscape, with some reconnaissance beyond—notably to locate the more remote mining sites.28 Over 1,500 archaeological structures have been recorded in this small zone, allowing our team to construct a multiperiod analysis of settlement, mineral exploitation, land use, and environmental change.29 The mines themselves are focused in several groups, with the main cluster just to the north and northeast of the main Roman smelting sites (see fig. 7.6). Detailed survey and classification of the workings, which comprise extensive shafts, adits, and galleries has been carried out by the Bochum mining museum, but the results are still only partially published.30

The mining works are far harder to date than production sites, and many of the more obvious adits and shafts may well have been exploited in more than one phase of extraction. Some of the most impressive evidence is found in the Wadi Khalid and the Qalb Ratiye about 1–3 kilometers north of the Wadi Faynan. The main Roman mines appear to have targeted low-grade massive brown sandstone (MBS) ores in the Qalb Ratiye, 2 kilometers north of Khirbat Faynan and at Umm al-Amad in the mountains to the south of the Faynan. The higher-grade dolomitelimestone-shale (DLS) ores previously exploited in the Bronze Age and Iron Age mining phases are believed by Hauptmann to have been worked out by this date, leading to the switch. However, some Roman ceramics and coins have been noted around mines in the Wadis Dana, Khalid and al-Abyad; when linked with the Nabataean/Roman date of the addition of a third shaft at a double-shaft Iron Age mine in the Wadi Khalid, this strongly suggests that there was some additional reworking of the DLS ore beds. However, the distinctive pollution signature of the Roman-period smelting activity indicates that the Roman mining operations overall focused predominantly on the MBS ore-beds.31

FIGURE 7.7 The Umm al-Amad mine gallery.

There is no doubt that the landscape impact of the mining activity has been considerable, as can be seen by the large deposits of mine tailings (waste) in the minor channels and the bed of the Wadi Dana and in other tributaries of the Wadi Faynan running down from the escarpment where the major exposures of the mineral-rich strata occurred.

To give some idea of the scale of the enterprise, I shall briefly describe the largest known mine chamber, which lies high in the mountains about 12 kilometers south of Khirbat Faynan. The entrance to Umm al-Amad (Mother of the Pillars) comprises a low slit supported on piers of unquarried rock in a near sheer cliff face. On my first visit in 1998, entering the mine involved a flat-out crawl over a dense layer of smouldering goat droppings, through acrid smoke—a truly unforgettable experience. Once inside, the chamber roof heightens, opening into a vast main gallery (120m x 55m, and up to 2.5m high) supported on rows of undug rock arches (see fig. 7.7). The impression is breathtaking.32

FIGURE 7.8 Plan of Khirbat Ratiye and associated structures—probably housing for the mine workforce. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

The archaeology of the Wadi Faynan focuses on Khirbat Faynan (WF1), the large settlement at the junction of the three main tributaries of the upper Wadi Faynan—the Wadis Dana, Ghuwayr, and Shayqar (see fig. 7.6)—with an impressive group of associated sites: the South Cemetery, an aqueduct, a water pool and mill, slag heaps, and an extensive field system that extends down the Wadi Faynan to the west (WF4). This site is without doubt to be identified with ancient Phaino, the center of Roman copper mining in the Jordanian desert.33 The preserved remains have the character of a mining town, ornamented in late antiquity with a series of churches—these latter reflecting the fact that it became a focus of pilgrimage following the martyrdom of Christians there during the Great Persecution.34 At Khirbat Faynan itself, the extensive and dense settlement suggests an urban center with a fortified administrative building at its center (see fig. 7.5).35

The Qalb Ratiye mines were controlled by a large fortified building Khirbat Ratiye (WF1415), again suggesting the presence of some soldiers and a small bureaucracy, while the simple huts gathered around the enclosure may well have housed the miners themselves (see fig. 7.8).36 Although major settlement concentrates on the two Khirbats, some smaller settlements are dispersed across the landscape. A number of village-like settlements are known close to the mountain face and some of these could potentially have housed miners and mining-related personnel.37 On the other hand, some well-built farms that had existed in the landscape in the Nabataean period appear to have been abandoned—perhaps a sign of increased centralization of land and control in the valley.38

Smelting activity in the landscape was quite widely dispersed in the Bronze Age and Iron Age periods, but in the Roman period, smelting appears to have been almost exclusively concentrated at Khirbat Faynan, where the main visible slag heaps are of Roman date. The implications of this are important, as Roman activity is attested at a number of separate mining sites—from where the ore was evidently transported for centralized processing. The thick-walled furnaces and large tap slags of the Roman period indicate very intensive and large-scale production.39

The great field system WF4, covering over 100 hectares (250 acres) and extending over 5 kilometers west from the Khirbat Faynan, was already partially developed in pre-Roman times.40 A series of “Nabataean” farms have been located in connection with discrete subareas of the overall field system. Analysis of surface pottery suggests that these sites did not continue in occupation into the Roman period. One possible interpretation of this is that the control of land was also centralized and unified under Rome, with farming henceforth carried out by people based in the main settlement at Phaino.41 The technology of the runoff and floodwater farming systems here was designed to combat the essential background aridity and sustain a level of agriculture normally reserved for a better-watered zone. Productivity was thus artificially raised above the normal carrying capacity of such a landscape, but in so marginal a zone its long term maintenance was fragile. A peculiarity of the field system is that large parts of it are carpeted in dense ceramic scatters of broadly Roman-Byzantine date, despite the absence of substantial dwellings of this phase within the fields (see fig. 7.9).42 The explanation for this anomalously high shard density lies in the pollution history of the Roman landscape.

FIGURE 7.9 Shard density within the Roman/Byzantine developed field system. The high concentrations of shards, especially in the northern fields, almost certainly indicate intense manuring of the prime agricultural land to try to counteract declining productivity of the land as a result of intense industrial pollution. The southern fields are more steeply terraced and were probably exploited primarily for vines and olives. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

The archaeological character of the Roman settlement and activity appears to have been very different to that of the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Nabataean periods and appears to testify to a high degree of centralized control. The new evidence of this archaeological landscape can now be compared with the scant historical documentation about the area.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT

As has been noted already, Khirbat Faynan is almost certainly to be identified with ancient Phaino, the infamous center of Roman copper mining in the Jordanian desert and scene of horrific persecution of Christians in the fourth century AD.43 Little is known of the site before it entered Eusebius’s account of the Great Persecution, but it was clearly at that date under imperial control and being managed as part of the res privata of the emperor. It is plausible, though at present unprovable, that the copper mines had been taken into state ownership at the time of the Roman annexation of Nabataea in AD 106—ore deposits were one of the key resources that drove imperial expansion (and helped pay for it). The essential story of the Roman period in the Wadi Faynan region is thus that of an imperial power refashioning a landscape in order to exploit its resources. As we shall see, the nature of the Roman settlement and activity falls outside the norms of what one might expect of such a region. The operation of Rome’s imperial economy can be read in the landscape that resulted.

When they annexed the Nabataean kingdom in AD 106,44 the Romans would already have known that the exploitation of copper was well established in Faynan, and the abundance of Nabataean wares and an apparent Nabataean date for extensive parts of the large field system show that support infrastructures were in place.45 Nonetheless, it seems clear that imperial incorporation led to an intensification and reorganization of metal production here that was to have profound consequences. First, let us consider the practicalities of the Roman takeover of the mines and of the settlement of Phaino. The Roman state claimed ownership of all significant mineral deposits and decorative stones,46 though the exploitation of these was variously handled. Sometimes, the imperial monopoly was strictly maintained by the direct management of mining activities by imperial officials (military prefects or civil procurators), in other cases the rights of exploitation were leased to private companies, who contracted with the state to hand over a fixed percentage of the output.47

A good example of the former type of control concerns the extraordinary measures put into effect to exploit the granites and porphry of the Eastern Egyptian desert.48 The scale, complexity and expense of the enterprise there is revealed by the establishment and maintenance of quarries, slipways and workshops, forts and fortlets, settlements for workers, animal feeding stations, wells, tracks and roads, and massive wheeled vehicles to transport 200–metric ton columns across the desert to the Nile.49 The research has also highlighted the need to assemble and provision a very large and skilled workforce. The documentary records of the quarry sites, in the form of many ostraca (documents written in ink on pottery shards) on site and associated papyrological evidence, reveal a high level of organization of everything from orders for bread to the requisitioning of hundreds of draft animals (principally camels) from settlements along the Nile and in the Fayum.50 They also demonstrate that most of the quarry workers were paid wage earners not the slaves or forced labor of popular imagination.51 The palaeobotanical studies of Marijke van der Veen have demonstrated that the diet of many of the people at the quarries was better than had been previously imagined (when a predominantly slave labor force was envisaged) but the vast bulk of those foodstuffs were evidently produced in the Nile Valley several days journey to the west and imported.52 Fish bones indicate that some commodities were also obtained from the Red Sea ports on the coast to the east of the mines. The pottery assemblages are also revealing of the supply mechanisms of an imperial operation.53 What the Egyptian quarries highlight are the lengths and expense that the Roman state was prepared to go to control the supply of both everyday necessities and of selected high-status commodities.

It is likely that the organization of the Faynan copper mines was not dissimilar in type, if not in every detail. There is certainly every indication that Phaino was one of the largest mining centers in the Roman eastern Mediterranean and was almost certainly under direct imperial control judging by late Roman references to Christians being condemned to work in the mines there. But unlike the Egyptian desert, there is no trace here of a major military camp at the heart of the mining district, though the literary sources imply the presence of some troops. The scale of the major buildings at Khirbat Faynan and Khirbat Ratiye suggest that we are dealing with fortlets manned by small groups of troops and this has implications for the nature of the workforce—commonly assumed to have primarily comprised slaves and forced labor.

The historical documentation, centered on two works of Eusebius of Caesarea, paints an horrific picture of Roman judicial savagery against the Christians sent to Phaino.54 It is important to put the use of condemned labor in Roman mines into context, as the popular image derived from the sensational accounts of writers such as Eusebius is misleading in certain respects: “Of the martyrs in Palestine, Silvanus, bishop of the churches about Gaza, was beheaded at the copper mine at Phaino with others, in number forty save one; and Egyptians there, Peleus and Nilus, bishops, together with others endured death by fire.”55

In AD 302, Diocletian and Maximian wrote to the proconsul of Africa instructing him to ignore customary rules of status in dealing with Manicheens—contrary to normal practice, if guilty, even rich people were to be sent to the mines of Phaino or the imperial quarries of Proconnesos. This demonstrates that Phaino was certainly under imperial control at that date, and evidently one of the larger mining centers in the east. But we should note that condemning people to the mines was conceived primarily as an extreme punishment (a deferred death sentence). In a later persecution of the mid-fourth century, the Arians in Alexandria “demanded that … [Eutychius, a subdeacon] should be sent away to the mines; and not simply to any mine but to that of Phaino where even a condemned murderer is hardly able to live a few days.”56 Some groups of Christians were physically disabled before being shipped there, some being lamed, others emasculated.57 Another group of Christians sent from Egypt had the left leg tendon severed and the right eye gouged out before arriving at the mines.58 A crucial aspect of such mutilation was that it made convict labor easier to supervise by a limited number of overseers or a small military contingent.

One could easily conclude that slaves and condemned prisoners made up the vast bulk of the workforce at Phaino and that the severe and extreme measures taken against Christians sent there in the period 303–13 were a normal pattern of brutality at the mines. The reality was almost certainly rather different.

The question is, how normal was the situation recorded by Eusebius? Fergus Millar’s study of the legislation condemning people ad metallum is a valuable starting point for considering the true nature of such punishment.59 The Roman state had possibly been sending people to Faynan as a form of capital sentence ever since the annexation of Nabataea in AD 106. My guess is that numbers may not have been particularly large per year, but Roman justice probably ensured a steady flow of people of generally low status and low importance. This practice continued into late antiquity, but it was only when Christians (including people of wealth, education, and status) entered this world, suffered martyrdom, and were subsequently remembered by hagiographers such as Eusebius, that the spotlight of history is turned on this issue. This applies not only to the Great Persecution of 303–12, but also to later persecutions of Catholics by Arian Christians in the AD 350s and again in the 360s and 370s, when the fate of educated Christians in the mines of Phaino again became a matter of record. It is equally clear that persecution of the Christians produced not simply high-profile individual victims but also unexpectedly large numbers of them in the justice system. Entire communities were arraigned, and to the surprise of the imperial authorities, refused en masse to yield to the threats and persuasions of the Roman judicial system. Given the chance to recant, and knowing the awful consequences of persisting, the more committed Christians refused to renounce their faith. This was an unanticipated outcome and the necessity of enforcing the threatened punishment—with the dispatch to the mines of hundreds of ordinary people (men, women, and children)—must have imposed a burden on the Roman system of supervised forced labor. There are thus grounds for doubting the typicality of the picture of treatment of Christians condemned to the mines.

In this light, I think it is possible to reconstruct something of what occurred at the height of the persecutions from Eusebius’s highly emotive account. From AD 306 onward, increasing numbers of Christians were transported from Egypt and Palestine and some at least of these were prejudicially maimed before being sent to “dig for copper.”60 At first small numbers may have been involved, but as the persecution grew in scale and intensity, it appears that large groups of Christians were sentenced en bloc to the mines at Phaino.61 The majority of them were evidently housed there in communal “barracks.”62 It is difficult to come up with hard figures, but it appears that several hundred people may have been sent there over a five-year period and this may have presented unforeseen problems for the officials and soldiers stationed at the mine. With unprecedented numbers of condemned people being sent there, some even with their families, supervision and control of the workforce (and with it the security of the operation) could have been compromised. The maiming of some of the groups prior to dispatch to Phaino could be a consequence of this. It certainly does not seem to have been routine practice.

The presence of so many Christians, including several bishops, led to the growth of a Christian community with “houses for church assemblies,”63 appointing its own bishop,64 and, because they were denied written scriptures, listening to recitation by a blind Egyptian who knew them by heart.65 It appears that those who became too old or infirm to work in the mines were allowed to live on, fasting and praying, in a separate settlement near the mines and this evidently became a special focus of the Christian community, led by the Bishop Silvanus and the blind “reader” John.66 Despite a presumably high mortality rate, the community was periodically reinforced as new batches of Christians were sent there; in 306–7, most arrivals appear to have been from Palestine and Gaza; in 308–9 we hear of two groups from Egypt, one comprising 97 men, women, and children, and another of about 65 (detached from a group of 130 condemned Christians).

However, a major disaster befell the Christian community in AD 311, after the Roman governor of Palestine, Firmilianus, had visited Phaino and, observing the growing strength of the Christian community in bondage there, wrote to the emperor Maximin to inform him about it.67 The emperor then demanded a purge of the Christians at Phaino, which was carried out by the superintendent of the mines, supported by a military commander, or dux (presumably these were the two key imperial officials on the ground at Phaino). The measures taken included, first, the execution (by decapitation or burning) of people identified as the leaders of the Christian community—the Palestinian bishop Silvanus of Gaza and four Egyptians (two bishops, Peleus and Nilus, and two of the laity, Patermuthius and Elijah); second, the decapitation of all those who were “shattered by age or sickness in the mines, and those who were unable to work”; and, third, the dispersal of the remaining “able-bodied” Christians among a number of other mines and quarries in the Levant (Cyprus, Lebanon, Palestine).68 The old and infirm group comprised Silvanus and thirty-nine other “confessors,” who were evidently executed “in a single day,” suggesting a brutal and sudden move against the Christian community at the mines.

The Christian martyr tradition at Phaino was not based, therefore, on the large number of deaths that probably occurred there as a result of injury, sickness, or routine ill-treatment. Rather it related to a specific set of historical events in AD 311, probably lasting a few days only, in which soldiers at the mines executed a number of the leading Christians, along with all those incapable of further physical work, and forcibly broke up the Christian community. It suggests that there was a realization on the part of the Roman authorities that the policy of sending Christians en masse to Phaino had been a mistake, in that it had created unexpected problems of control at a mine that lacked a major military garrison post. The effect of the purge was to break up the Christian community that had flourished in the absence of strong supervision and to eradicate those unfit for hard labor. The logical conclusion to be drawn from this is that—although used to dealing with some condemned prisoners—the mines in Faynan were not normally run as a large-scale penal colony with a big military garrison. This seems to fit with the archaeological evidence.

It is thus likely that at no time would condemned people have made up the entirety of the labor force and that normally they served hard labor alongside people who were paid good salaries (by ancient world standards) for doing specialized and often highly technical work. That is increasingly clear from mining and quarry sites elsewhere in the Roman world, where slaves and criminals are virtually unheard of in surviving documentation, but salaried staff are now well attested on ostraca, inscriptions, papyri, writing tablets, and the like.69 Problems with using slave labor include the fact that it requires constant supervision and that it is difficult to motivate other than by brutality (which reduces the working life of many of its victims). Free labor can sometimes be encouraged by differential pay scales to work more diligently and with a higher degree of technical skill. Many aspects of mining and smelting involve a high level of knowledge and technique as well as brawn. On the other hand, the Roman Empire had a tradition of disposing of some of its condemned criminals and dissidents to the mines and quarries as disposable labor in dangerous and heavy work. The logical conclusion is that, as an imperially controlled mining center, Phaino drew on a mixed pool of forced labor and free (perhaps migrant) workers. We know soldiers were present, but they appear to have been relatively few in number. If the overall labor force at the mines was suddenly increased this would have had implications not only for supervision of the mine works, but also for logistical supply. It is for these reasons that the influx of large numbers of unrepentant Christians would have presented problems for the mining authorities and created a situation that was rather abnormal.

Nonetheless, the account of the Christian sources provide several important insights into the working of the mines: we learn that some workers were housed in barracks-like accommodations; there was a community of people not directly involved in the mining and smelting operations and this was separated in some way from the main center of habitation; some forced labor was involved in work inside the mines; and there was an inspector of mines and a military officer at Phaino. A possible way to correlate this with the available archaeological data is to assume that the mining and smelting operations were administratively highly centralized at Faynan and that some of the mining workforce, along with the smelting crews, administrative personnel and military backup was accommodated in structures on the north and south banks of the Wadi Ghuwayr, close to the major Roman slag heaps (WF1 and WF11). The separate community of Christians no longer able to work must clearly have been fairly close at hand, even if physically distinct from the rest of the mining settlement. One possibility is that it was located on the east bank of the Wadi Shayqar in the area known as WF2, close to the location of a later church and Christian cemetery (perhaps reflecting a continued importance of that zone for the Byzantine Christian community).

There were clearly some significant changes in the Byzantine period when Faynan became a center of Christian pilgrimage on account of the martyrs, and a sizable Christian community lived at the site (and almost certainly continued to work as free labor in the mines). Bishops of Phaino are mentioned in church councils and synods of 431, 449, 518, and 536, and a Bishop Theodore is attested in an inscription from WF1 in 587–88.70

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

As we have seen, the town of Phaino served as the center for the administration of the mining district, and was the location where virtually all the smelting activity was centralized. Throughout the mountain front there were numerous mines, though the main concentration of Roman galleries were in the Ratiye Valley a few kilometers to the north of Khirbat Faynan. The major field system (WF4) was a key resource for the food supply of the mining community. All these elements (town, mines, smelting sites, and field systems) appear to have been under direct state control.

The human impact of the Roman organization of the mines at Faynan can be summarized as follows:

• There is a likelihood that the entire zone of the mines was taken into state ownership, with central authority over the district being exercised by Roman officials, perhaps backed by a few troops, based at Phaino.

• Some of the labor for the mines is believed to have been provided by slaves or convicts, but some of the mining personnel and certainly the more specialist engineering and metallurgical roles would have depended on a salaried labor force, as in other imperial mining and quarrying operations.

• Ownership of the territory around the mines allowed the state to organize food production within the runoff agriculture zone in a more unified way, possibly with an agricultural labor force also being maintained on site.

• The isolation of the mining district and the distance of many of the mines from the centralized smelting facilities at Phaino would have required a large number of draft animals and animal handlers to be based at the site on a year-round basis to transport the ore from the actual mines to the furnaces, and to bring in supplies of fuel and perhaps additional foodstuffs. All this would have greatly added to the needs of the settlement for food and water provision.

• The mine would have been a heavy net consumer of people given the dangerous and demanding nature of the work, and the intrinsic unhealthiness of smelting for everyone living in close proximity.

• Even if there is little evidence for a heavy military garrison in the Wadi Faynan, it is clear that this was a landscape of significant control and surveillance.71

An important component of the work of the Wadi Faynan project has been the investigation of the pollution signature of the ancient mining and smelting activity and an assessment of its impact on the landscape and people of the region.72 There is now compelling evidence to demonstrate that the Roman landscape in the Faynan was severely compromised by the scale of smelting activity (see fig. 7.10). The aridity and polluted nature of the environment of the Wadi Faynan thus posed serious problems for the Roman administrators of the mines as far as

• how to sustain a large labor force in the pre-desert landscape on a year-round basis (food and water)

• how to supply the fuel requirements of large-scale metal smelting (timber and charcoal)

• how to combat the negative impacts on population and landscape of the local pollution produced by intensive metallurgy

That Roman mining activity here extended well into the Byzantine period was both a triumph and a disaster. What we have in the Wadi Faynan is a landscape that was systematically organized and comprehensively despoiled by the Romans. The well-known phrase of Tacitus, “Where they make a desert, they call it peace,” has a particular resonance in the context of the evidence for the environmental degradation and pollution in Faynan.73 It is to those aspects of the mining and smelting regime that we should now turn.

Hauptmann’s estimate of Roman copper production at 2,500–7,000 metric tons should probably be seen as a minimum order of magnitude range, with a distinct possibility that actual production exceeded this level. Extrapolated on a four-hundred-year production period, the average annual copper yield of the mines based on Hauptmann’s figures would have been in the order of 6.25–17.5 metric tons per year.74

The production of 6.25–17.5 metric tons of copper each year would have necessitated the smelting of about 60–175 metric tons of ore, consuming around 80–258 metric tons of charcoal.75 Perhaps unsurprisingly in a pre-desert environment, there are indications of diminishing local supplies of suitable timber over time, with the possibility that large quantities of wood or charcoal were brought into the mining center on pack animals. It is clear that by the Roman period charcoal for the furnaces was brought in from the plateau above, whereas in the Iron Age a wide array of trees and scrub grew locally.76 There are significant implications from this. The 80–258 metric tons of charcoal represents 1,200–4,000 donkey loads per year. Movement of the 60–175 metric tons of ore within the mining region from mine to smelters necessitated a further 900–2,600 donkey loads. Similarly, the copper produced at Faynan would have entailed an average of between 100 and 250 donkey loads annually for its export from the mines. The food supply needs of the mining community may have been as high as an additional 2,800 loads annually.

Added together, the import of foodstuffs and other goods not produced locally, the movement of ore from the mines to the smelters, and the import of charcoal for the furnaces and the export of copper (under suitable security arrangements) must have accounted for a considerable number of pack animals (probably mostly camels or donkeys). The fodder needs of these animals was an additional burden on the system, perhaps met by a combination of additional grain imports and by exploiting available grazing within the valley. If the landscape was extensively grazed by pack animals associated with the mines this has implications for the access to this resource of contemporary pre-desert pastoral groups. Supplying and feeding the mining operations would have become more difficult over time, with charcoal and other fuel having to be fetched from longer distances and grazing resources in the valley potentially reduced.

What about the potential for growing food within the valley? The selection of the Wadi Faynan as the Roman mining center was undoubtedly connected with the fact that there was a good water supply in the Wadi Ghuwayr and the largest expanse of potentially cultivable land in the Araba region. This could only be exploited through the use of runoff farming technology, exploiting the seasonal rainfall and flash floods of the area.77 Progressive additions to the field system increased its integral nature, its scale, and its hydraulic sophistication. The technology of the runoff and floodwater farming systems here was designed to combat the essential background aridity and sustain a level of agriculture normally reserved for a better-watered zone. Productivity was thus being artificially raised above the normal carrying capacity of such a landscape, but in so marginal a zone its long-term maintenance was fragile.

FIGURE 7.10 Graph demonstrating Roman date of pollution levels in a section excavated behind a barrage. The peak levels of a wide range of pollutants (beryllium, copper, arsenic, strontium, thallium, lead) can be equated with the more extreme pollution incidents of modern industrial metallurgical extraction and processing. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

FIGURE 7.11 Declining modern plant fertility with distance from Roman slag heaps in the Wadi Faynan. (From Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007.)

As already observed, a peculiarity of the field system is that large parts of it are carpeted in dense spreads of broken potery of broadly Roman-Byzantine date. The geochemical analyses have demonstrated the degree to which the landscape was affected by toxic pollution from the largescale smelting activity around the Khirbat. Brian Pyatt and John Grattan have demonstrated the continuing effects of pollution in the modern landscape of Faynan on plant fertility. The pollution reduces the yield of seed production on wild barley plants close to the major slag heaps to about 50 percent of the yield of plants 1 kilometer away. There is a demonstrable and progressive decline in plant fertility as one approaches the slag heap—an obvious pollution hot spot (see fig. 7.11).78

The intense smelting activity around Khirbat Faynan would have produced a dense pall of airborne pollution, from which many particles would have entered the ecosystem by falling on crops, bare fields, and the uncultivated landscape—where it would have been taken up by wild plants. The extent of Roman pollution can be guaged in part from our studies of pollution signatures in buried soil horizons close to the smelters, to the presence of toxins in samples of human bone from Byzantine cemeteries and from the continuing significant levels of heavy metals in present-day vegetation, invertebrates, and grazing animals. Radiocarbon dating of the deep sequence of deposits that built up behind a Roman barrage wall adjacent to Khirbat Faynan provides a consistent picture of the Roman/Byzantine period as a time of peak levels of heavy metal pollution from the smelting activity.79

From an area of probable Roman ore washing and intense smelting adjacent to the Khirbat Faynan, the occurrence of a broad and deadly cocktail of poisons at drastically unsafe levels is a signal demonstration of the hazards to human health that the metallurgical production posed (see fig. 7.10).80 The revelation that high levels of the pollutants are still present even in modern vegetation and fauna living or grazing close to the major slag heaps is still more alarming. The local bedouin have for generations raised goats that are renown in Jordan for their resistance to common goat parasites. Pollution studies of samples of modern goat milk, urine, and hair now suggest that the explanation of this is that the goats have highly toxic guts that are not welcoming to parasites! Of even more concern for our research project was the demonstration that the dust particles within modern bedouin tents (where the team’s daily flatbread was produced using imported flour) contaminated the finished product.81 It is clear that the ancient mining community lived in a toxic landscape, where their food and water supplies were readily compromised by airborne pollution. Their health was further affected by their daily handling of toxic mine waste, ores, slags, and other waste materials.

It is also highly likely that ancient attempts to counter pollution in the landscape may simply have exacerbated the effects. Although perhaps not understood at the time as a consequence of pollution, problems of diminished plant or soil fertility can hardly have gone unremarked in antiquity. Study of the dense carpet of pottery within the field system is informative here. Some of the shards relate to pre-Roman sites and structures, but the vast bulk of the material dates to the later phases of use (late Roman–Byzantine) when the bioaccumulation of toxic material within the soil would have been at its worst.

Thus, the dense carpet of shards in the fields (and the relative absence of major rubbish deposits around Khirbat Faynan itself) almost certainly indicates a sustained and large-scale collection of domestic and household waste from the major settlement and the manuring of the land with it.82 Human and animal waste has been known to improve soil and crop fertility since antiquity, and this was the obvious strategy for the ancient farmers of Faynan to adopt in response to declining yields. However, the ancient inhabitants of Faynan cannot have appreciated that the unfortunate side effect of this policy was to add the fraction of heavy metal components excreted by humans and animals to the farmland. Over time this would have increased the level of heavy metals in the soil—and thus in the crops grown on the land (making them more dangerous to those who consumed them). The fertilizing effect of manuring would equally have been increasingly nullified by the higher levels of pollution. If manuring was perceived as a simple remedy to falling productivity, it was in fact almost certainly a factor in exacerbating it.

FIGURE 7.12 Pollution levels in Byzantine skeletons from the mining settlement at Khirbat Faynan, with dashed line indicating “safe” occurrence. (From Grattan et al. 2002.)

The effects on human health of exposure to the metallurgical pollution can be predicted by comparison with better-documented studies of industrialized production.83 Copper and lead are well known poisons and both occurred at very dangerous levels in the Faynan ores. There is a large catalog of other contaminants and poisons present here—arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, mercury, thallium (see fig. 7.10). Ingestion of these toxins could lead to death from a variety of complications, but the overall cocktail is likely to have been a significant factor in reduced life expectancy for all exposed to it. The high levels of copper, lead, and other harmful contaminants would have made this population exceptionally vulnerable to any significant epidemic. This has been corroborated by studies of bioaccumulation of these same pollutants in human skeletons from the Byzantine cemetery (see fig. 7.12).84 Two tombstones from the South Cemetery (WF3), evidently dating to AD 455–56, commemorated not only individual deaths but some exceptional event that had led to “the death of a third of the community.”85 The population tended to die young and needed continuous reinforcement from outside the valley, whether in the form of convict labor or free workers attracted by the higher than average wages paid by such operations. It is a terrible irony that far more Christians evidently died at Faynan after the persecutions, when they chose voluntarily to go and live and work there, than during them.

CONCLUSION

The new data from the Wadi Faynan survey provides a particularly graphic picture of the potential impacts of a Roman mining operation. The environmental and human damage inflicted by the metalla at Phaino are now well delineated. The infamous events of the Great Persecution there can also be more fully assessed within the context of a long-term mining operation and the extraordinary nature of the precise events of AD 303–12 understood. The story of Rome’s exploitation of metals from a remote desert region represents in a microcosm key elements of the Roman imperial economy outlined in chapter 5. What we have here is an operation that defies normal rules of economic rationality in the service of a superstate. The ecological and human consequences of the rape of this landscape were profound in antiquity and are still with us to the present day.86

Versions of this chapter have been delivered as lectures or at various conferences in Oxford, Leicester, St. Andrews, and London, England and Aberystwyth, Wales.

1 Comparison with the Chinese empire may be instructive to set this profligacy in perspective; see Portal 2007. At the very least, the Roman emperors’ behavior does not seem to have been particularly unusual.

2 Pliny, Natural History, 6.101, 12.84; De Romanis and Tchernia 1997; Tomber 2008.

3 Ying 2004.

4 While the hemispheric pollution represented on Greenland could have implicated China, India and Parthia/Persia also, there is general agreement that the Roman contribution to this pollution picture was likely to have been large.

5 Hong et al. 1994, 1996. See Wilson 2007 for reflections on the implications of this for Roman metallurgical production.

6 Mines: Davies 1935; Domergue 1990, 2008; Orejas 2001, 2003. Quarries: Maxfield 2001; Maxfield and Peacock 2001a, 2001b; Peacock and Maxfield 1997, 2007.

7 Hirt 2004; Granino Cecerere and Morizio 2007.

8 Polybius, Histories, 34.9.9; Strabo, Geography, 3.2.10.

9 Pliny, Natural History, 33.4.78.

10 Sánchez-Palencia. 2000, esp. 156–57.

11 Sanchez Palencia 2000, 189–207; cf. also, Sanchez Palencia et al. 1996.

12 See Wilson 2007 for a good discussion of the archaeological, epigraphic, numismatic, and environmental data.

13 Hanson and Haynes 2004; Oltean 2007.

14 Bartels et al. 2008, 113–96.

15 Garnsey and Whittaker 1998.

16 Garrard 1982; cf. Wilson 2007, 122–23, for an up-to-date review of the evidence.

17 Salgado 1993.

18 Sanchez-Palencia 2000, 252–306. For the edict, see Sanchez-Palencia and Mangas 2000.

19 Hingley 2005, 102–5.

20 See Millar 1984 for an excellent overall review.

21 Tacitus, Agricola, 12.6: Fert Britannia aurum et argentum et alia metalla, pretium victoriae.

22 See Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007 for the published final report; see also Barker 2000, 2002; Barker and Mattingly 2007; and Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 for interim statements and other relevant publications.

23 On the impressive work of the Deutches Bergbau-Museum see, among others, Hauptmann 2000, 2007; on Timna, see Rothenberg 1999a, 1999b.

24 Hauptmann 2007, 94–109; Hauptman et al. 1992, 3, 21.

25 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 291–303.

26 Hauptmann 2000, 97; 2007, 52–53, 147.

27 Freeman 2001, 433–44; Talbert 2000, maps 70–71; Tsafrir, Di Segni, and Green 1994.

28 See Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 3–57, for the topography of Faynan and the background to the survey.

29 See Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 98–140, for an overview of site typology, and 305–48 for a summary of the Roman and Byzantine evidence.

30 Weisgerber 1989, 1996, 2003; a general listing of the Bochum Bergbau Museum’s surveys of mining and smelting sites is provided in Hauptmann 2000, 62–100, and 2007, 85–156. Cf. Willies 1991 for a detailed survey of a Roman mine close to Timna.

31 On the pollution signatures and the ores, see Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 311–12, 340–43.

32 Hauptmann 2000, 94–95; cf. Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 311, figs. 10.3–10.4.

33 Lagrange 1898; 1900.

34 Sartre 1993, 139–42.

35 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 313–19.

36 Ibid., 319–21.

37 Ibid.,, 321–25.

38 Ibid., 295–301, 325.

39 Ibid., 313, 321.

40 Ibid., 140–74, 295–301, 327–33.

41 Ibid., 327–31.

42 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 166–69.

43 Sartre 1993, 139–42.

44 For another client kingdom taken down by Rome under suspicious circumstances, see chapter 3 of the present volume.

45 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 293–94, figs 9.19–9.20.

46 Suetonius, Tiberius, 49.2.

47 Hirt 2004.

48 Maxfield and Peacock 2001a, 2001b; Peacock and Maxfield 1997, 2007.

49 See Maxfield 2001, 2003, for succinct summary accounts.

50 Adams 2001 details the complex arrangements made for requisitioning animals.

51 Cuvigny 1996.

52 Van der Veen 1998, 2001; Van der Veen and Tabinor 2007.

53 Tomber 1996.

54 Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine (MP) and Ecclesiastical History (EH). See Gustafson 1994 for a discussion of the literary evidence but lacking knowledge of the archaeological correlates.

55 Eusebius, EH, 8.13.5.

56 Athanasius, Orations against the Arians, 60.765–66.

57 Eusebius, MP, 7.4.

58 Ibid., 13.1–3.

59 Millar 1984.

60 Eusebius, MP, 13.1–3.

61 Ibid., 5.2, 7.2.

62 Ibid., 13.4.

63 Ibid., 13.1–3.

64 Ibid., 13.4.

65 Ibid., 13.6–8.

66 Ibid., 13.1, 13.9–10.

67 Ibid., 13.1–3.

68 Ibid.,13.9–10.

69 Maxfield 2001, 154–55; 2003.

70 Sartre 1993, 142, 145–46.

71 This is a theme developed in an unpublished PhD thesis by my student Hannah Friedman (2008).

72 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 334–48; Grattan et al. 2002, 2003, 2004; Grattan, Huxley, and Pyatt 2003; Pyatt et al. 1999, 2000, 2005.

73 Tacitus, Agricola, 30: ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant.

74 Hauptmann 2000, 97.

75 Figures derived from Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 345–46; for a slightly different set of estimates, cf. the figures in Rihll 2001.

76 Barker 2002, 501; Engel 1993; Engel and Frey 1996; cf. Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 344–46.

77 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 150–74; cf. Barker et al. 1996a, 191–225.

78 Barker et al. 2000, 44–45; Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 86–89.

79 Barker et al. 2000, 44–46; 2007, 335–43.

80 Grattan et al. 2003.

81 Grattan, Huxley, and Pyatt 2003.

82 See Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 328–32, 348 for a fuller discussion.

83 Ibid., 340–43, 410–12; Grattan et al. 2002.

84 Grattan et al. 2002.

85 Sartre 1993, nos. 107–8.

86 Barker, Gilbertson, and Mattingly 2007, 38–57, 369–95, for discussion of the modern bedouin population of Faynan.