67 | CLINICAL FEATURES AND PATHOGENESIS OF FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA

GEORGES NAASAN AND BRUCE MILLER

First described by Pick in 1892 as frontal lobe dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) was neglected for almost a century before re-emerging as a clinically important neurodegenerative disease. It is the second most common dementia in patients under the age of 65 and the third, after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), in the elderly population. In neuropathological studies, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) was found to be the third leading neuropathological diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases with a prevalence of 4% after AD (42%) and vascular disease (VD; 23.7% isolated and 21.6% in combination with AD) (Brunnstrom et al., 2009).

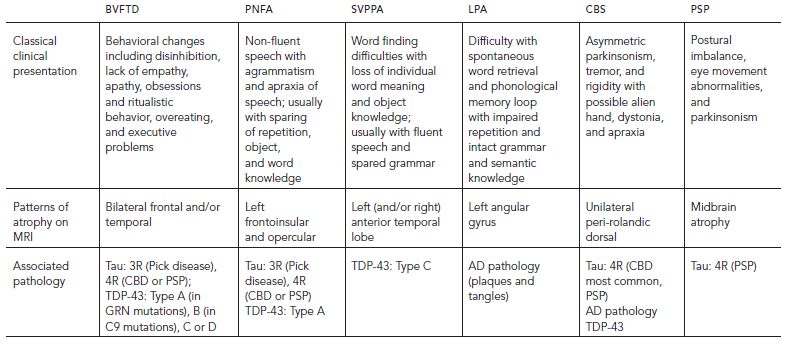

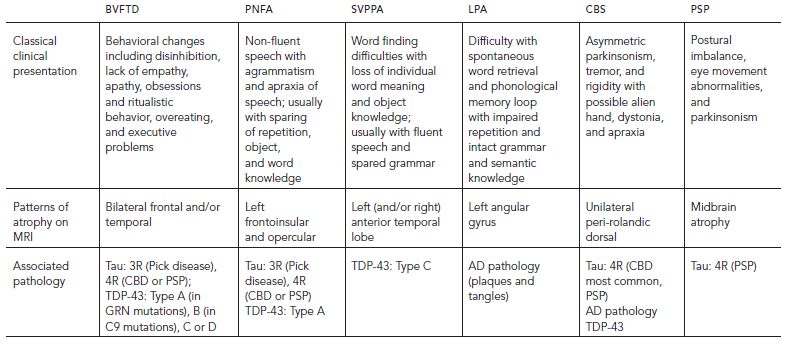

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is used to describe a group of clinical syndromes that are caused by frontal and/or temporal lobe dysfunction with a relative preservation of the posterior brain structures that are typically involved in AD and DLB. The clinical presentation of FTD is insidious and slowly progressive. The predominant symptom can be behavioral changes (orbitofrontal, medial frontal, and/or anterior temporal lobe), executive function impairment (dorsolateral frontal), and/or language impairment (perisylvian, frontoinsular, or anterior temporal lobe) giving rise to various clinical subtypes that are summarized in Table 67.1.

The term frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) refers to the pathological syndrome associated with predominant frontal and/or temporal lobe atrophy (Cairns et al., 2007). Most FTLD cases show neuronal aggregates of tau, TDP-43, or FUS. Some FTD subtypes overlap with other neurological syndromes, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease (FTD-MND) (Caselli et al., 1993; Lomen-Hoerth et al., 2002; Neary et al., 1990; Neary et al., 2000) and parkinsonism in corticobasal syndrome (CBS) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Novel genetic mutations in familial and sporadic cases of FTD have been identified in the past decade and their implications continue to be a major subject of research.

Frontotemporal dementia represents a disorder of behavior that is caused by neurodegeneration, and this concept can be difficult for physicians to understand. Often, FTD is ascribed to conditions of the “psyche,” without making an attempt to understand them as caused by degeneration in specific brain structures. In addition, patients with FTD may present fairly young, sometimes in their young adulthood, which is the typical age at presentation for many psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disease.

Many examples of FTD being misdiagnosed as a psychiatric disorder are reported in the literature and expose the medical and social burdens of a misdiagnosis on patients and their caregivers (Khan et al., 2012b). Approximately 30% of patients with a neurodegenerative disease are initially erroneously diagnosed as having a psychiatric illness, especially when the predominant presentation is behavioral issues (Woolley et al., 2011).

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DEMOGRAPHICS

The prevalence and incidence of FTD is variably reported and has been difficult to ascertain, partly because of the heterogeneity of the clinical syndromes and the pathological diagnoses that the terms FTD and FTLD encompass. It is likely that all of the previous studies have underestimated the true prevalence of FTD for a variety of reasons. First, many patients with FTD never get diagnosed and end up in mental institutions or prisons. Additionally, the co-association of FTD with memory difficulty, parkinsonian movement disorders, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis means that even when a neurodegenerative disorder is recognized, many FTD patients are classified as having another neurodegenerative condition.

Studies conducted by European investigators suggested that the prevalence of a clinical frontal-lobe predominant dementia was between 12% and 16% at autopsy (Brun, 1987; Greicius et al., 2002). The release of the Lund-Manchester criteria for the diagnosis of FTD in 1994 (The Lund and Manchester Groups, 1994), followed later by the publication of the Neary criteria in 1998, helped to establish a clinical framework from which researchers could attempt to determine the epidemiology of the disease (Neary et al., 1998). By applying those clinical criteria, the prevalence of FTD in the United Kingdom was found to be similar to that of AD in the age group of 45 to 65 and was estimated at 15 per 100,000 (Ratnavalli et al., 2002). In the Netherlands, the prevalence of FTD was found to be lower and peaked between the ages of 60 to 69 at 9.4 per 100,000. It was roughly four in 100,000 for the age groups 50 to 59 and 70 to 79 (Rosso et al., 2003). For individuals age 85 and greater, the prevalence of the frontal variant of FTD according to the Lund-Manchester criteria was calculated at 3% (Gislason et al., 2003).

TABLE 67.1. Clinical subtypes of frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia seems to peak in the sixth and seventh decades. The incidence of FTD was reported to be 2.2, 3.3, and 8.9 per 100,000 person-years in the age groups of 40 to 49, 50 to 59, and 60 to 69, respectively, as compared with 0.0, 3.3, and 88.9 for AD (Knopman et al., 2004). In the United Kingdom, the incidence of FTD in the age group of 45 to 64 was found to be 3.5 per 100,000 person-years as compared with 4.2 for AD (Mercy et al., 2008). The age of onset in FTD can vary according to the specific subtype of the disease. It is generally between 50 and 60 years of age and might be dependent on the underlying pathology and on genetic factors (Johnson et al., 2005; Rosso et al., 2003; Seelaar et al., 2008). Although patients with the bvFTD appear to have the earliest onset, patients with svPPA have an earlier onset than those with PNFA (Johnson et al., 2005).

In a study of the California State Alzheimer’s Disease Centers the frequency of FTD as a clinical diagnosis was different across ethnic differences: 4.2% in Asians and Pacific Islander and 4.7% in Caucasians, but was significantly less in Blacks (1.5%) and Latinos (2.4%) (Hou et al., 2006). Sadly most of this data was collected during the 1980s and 1990s when FTD was severely neglected and underdiagnosed in the United States, accounting for the low prevalence in this study.

The evidence for gender differences in FTD is conflicting. Although some studies report no significant differences (Hou et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2004; Mercy et al., 2008; Papageorgiou et al., 2009), others suggest that there is a male predominance in the behavioral and semantic subtypes and a female predominance in the non-fluent aphasia group (Ratnavalli et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2005). Frontotemporal dementia is strongly familial, and patients with FTD were reported to have a family history of dementia in 10% to 38% of the cases (Chow et al., 1999; Stevens et al., 1998). Psychiatric illnesses in these families, including major depression and schizoaffective disorders, were reported in 33% of patients with FTD (Chow et al., 1999).

Although the typical survival of patients with Alzheimer’s disease from the time of diagnosis to death is reported to be seven to 13 years from symptom onset (Garcin et al., 2009; Roberson et al., 2005), the survival of patients with FTD is shorter, ranging from 3.4 years for patients with bvFTD to closer to six years for those with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (Roberson et al., 2005).

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

BEHAVIORAL VARIANT OF FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA

Behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is the most common subtype of FTD (Johnson et al., 2005). An international consortium revised and published new criteria for the diagnosis of bvFTD in 2011 and compared their sensitivity with the previous criteria set forth by Neary in 1998 in 137 pathology confirmed cases of FTLD (Rascovsky et al., 2011). The new criteria were superior to the previous ones in picking up possible and probable bvFTD when it corresponded to a pathological diagnosis of FTLD. These criteria are summarized in Table 67.2.

Often bvFTD patients have little insight into their problems and interviewing an informant is essential in diagnosing bvFTD. In fact, in early stages, the diagnosis can be completely missed if patients are interviewed without an informant, and they can have an intact cognitive performance on routine neuropsychology testing (Miller et al., 1991).

TABLE 67.2. Diagnostic consensus criteria for FTD and PPA

|

BEHAVIORAL VARIANT OF FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA (BVFTD) I. Possible bvFTD (three out of the six following symptoms [a-f] should be present to meet criteria) A. Early behavioral disinhibition B. Early apathy or inertia C. Early loss of sympathy or empathy D. Early perseverative, sterotyped, or compulsive/ritualistic behavior E. Hyperorality and dietary changes F. Neuropsychological profile: executive/generation deficits with relative sparing of memory and visuospatial functions II. Probable bvFTD (all of the following [a–c] must be present) A. Meets criteria for possible bvFTD B. Exhibits significant functional decline C. Imaging results consistent with bvFTD III. Exclusion Criteria A. Pattern of deficits is better accounted for by other non-degenerative nervous system or medical disorders B. Behavioral disturbance is better accounted for by a psychiatric diagnosis C. Biomarkers strongly indicative of Alzheimer’s disease or other neurodegenerative process |

| PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA (PPA) |

|

I. Inclusion Criteria (All of a-c must be present) A. Most prominent clinical feature is difficulty with language B. Deficits are the principal cause of impaired daily living activities C. Aphasia should be the most prominent deficit at symptom onset and for the initial phases of the disease II. Exclusion Criteria A. Pattern of deficits is better accounted for by other non-degenerative nervous system or medical disorders B. Cognitive disturbance is better accounted for by a psychiatric diagnosis C. Prominent initial episodic memory, visual memory, and visuo-perceptual impairments D. Prominent initial behavioral disturbances III. Diagnostic Criteria for Non-fluent/Agrammatic Variant PPA (PNFA for progressive non-fluent aphasia) A. Clinical diagnosis of NFAV-PPA 1. Agrammatism in language production 2. Effortful, halting speech with apraxia of speech 3. Impaired comprehension of syntactically complex sentences 4. Spared single-word comprehension 5. Spared object knowledge B. Imaging-supported NFAV-PPA 1. Clinical diagnosis of NFAV-PPA 2. Imaging showing one or more of: a. Predominant left posterior fronto-insular atrophy on MRI b. Predominant left posterior fronto-insular hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT of PET IV. Diagnostic Criteria for Semantic Variant PPA (svPPA) A. Clinical diagnosis of SV-PPA 1. Poor confrontation naming 2. Impaired single-word comprehension 3. Poor object knowledge 4. Surface dyslexia and/or dysgraphia 5. Spared repetition 6. Spared motor speech (no distortions) and grammar B. Imaging-supported SV-PPA 1. Clinical diagnosis of SV-PPA 2. Imaging showing one or more of: a. Predominant anterior temporal lobe atrophy on MRI b. Predominant anterior temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET V. Diagnostic Criteria for Logopenic Variant PPA (LPA for logopenic progressive aphasia) A. Clinical diagnosis of LV-PPA 1. Impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech 2. Impaired repetition of sentences and phrases 3. Speech (phonological) errors in spontaneous speech and naming 4. Spared single-word comprehension and object knowledge 5. Spared motor speech (no distortions) 6. Absence of frank agrammatism B. Imaging supported diagnosis of LV-PPA 1. Clinical diagnosis of LV-PPA 2. Imaging must show one of: a. Predominant left posterior perisylvian or parietal atrophy on MRI b. Predominant left posterior perisylvian or parietal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET |

BEHAVIORAL VARIANT OF FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA

Patients with the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (see Case 1 later in chapter) often present initially to the psychiatry clinic with what appears to be a mania or depression, or to a marriage counselor because of marital problems. The first presenting symptom is often one of disinhibition and social inappropriateness (Miller et al., 1991). As an example, patients might become overly friendly, approaching strangers and starting conversations that are too personal or explicit. Excessive trust of strangers coupled with a difficulty in making sound judgments, can particularly make these individuals vulnerable to exploitation, both sexually and financially. In fact, many spouses may report that their loved ones were the subjects of an online or telephone prank involving investing suspicious amounts of money in unfounded organizations. Symptoms of disinhibition correlate mainly with a pattern of atrophy in the orbitofrontal cortex but can also involve the subgenual cingulate, medial prefrontal, and anterior temporal cortex, as well as the white matter tracts connecting those regions, as measured by voxel-based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging analysis (Hornberger et al., 2011; Peters et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2005).

Apathy, social withdrawal, and decreased motivation are often reported (Rosen et al., 2005). Informants may report a decrease in interest for previous hobbies and a general attitude of indifference. In an objective assessment of daytime activity using a wristwatch that measures motion, patients with bvFTD spent 25% of their day immobile compared with their caregivers, who spent 11% of their day immobile (Merrilees et al., 2012). Apathy was found to correlate with reduced gray matter density in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right ventromedial superior frontal gyrus, right anterior cingulate, right lateral orbitofrontal cortex, right caudate, right temporoparietal junction, and right posterior inferior and middle temporal gyri (Eslinger et al., 2012; Rosen et al., 2005; Zamboni et al., 2008). A subclassification of bvFTD presentations, separating between predominantly disinhibited and predominantly apathetic, was suggested in the past (Snowden et al., 2001); however, it was shown that most cases are often mixed, and if not, they mostly progressed to mixed within four years of disease duration (Le Ber et al., 2006).

Patients with bvFTD can make rude remarks or gestures without regard for other people’s feelings. They are often described as becoming self-centered and losing the ability to understand the feelings of others. Families often describe insensitivity to someone else’s illness or injury. Patients become emotionally distant and detached. This often creates a toxic dynamic for couples. Also, because the majority of the patients present at a younger age, children who may be in their early teenage years, or even younger, may complain that their father or mother had become less affectionate and less involved in their schooling and upbringing. Neuroanatomical correlates of empathy include the right anterior temporal and medial frontal regions in a large-scale correlation study by voxel-based morphometry analysis of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data (Rankin et al., 2006). Also, by similar methods, an impaired recognition of emotions, and specifically negative emotions such as sadness, correlated with right lateral inferior temporal and right middle temporal gyri (Rosen et al., 2006).

Patients with bvFTD can become obsessed with specific thoughts and display compulsory behavior, which may be either simple or complex. For example, there may be repetitive picking, chewing, lip smacking, or pacing; there may also be constant locking and unlocking, as well as rituals that can be bizarre in nature. Compulsions can also manifest as hoarding. Mental rigidity occurs and patients may become less flexible to changes in plans or routines. Examples include exercising at a specific hour every day, eating specific types of food at specific times of the day, and taking the same route when walking their dogs.

Informants often describe hyperorality and inability to refrain from eating, even after satiety is achieved. A change in diet and more specifically a craving for sweets is often reported, as well as eating non-food items. The excessive, compulsive eating can result in weight gain. Hyperorality can also manifest in excessive drinking of alcohol, smoking, or chewing gum. Hyperorality despite reported satiety was found to correlate with right orbitofrontal, insular, and striatal regions, supporting the hypothesis that this circuitry is involved in higher gustatory integration and internal satiety signaling (Woolley et al., 2007). In another study, overeating correlated with loss of tissue in the posterior hypothalamus (Piguet et al., 2011).

Neuropsychological testing in patients with bvFTD primarily reveals deficits in executive functions (Kramer et al., 2003), with a relative sparing of verbal and visual memory and performance that is error prone and perseverative. It is important to recognize that episodic memory can be impaired in bvFTD (Hodges et al., 2004), even in early stages, and especially in some genetic forms of the disease that involve the progranulin gene (van Swieten and Heutink, 2008). Rule violation errors on neuropsychological testing correlated with tissue loss in the right lateral prefrontal cortex (Possin et al., 2009). In contrast, executive function tasks seem to be more diffuse and invoke attention, and visuospatial and language networks. Specific tasks of the executive function testing can localize to a specific region of the brain. Verbal fluency, in which patients are asked to generate the maximum number of words they can think of that start with a specific letter in one minute, correlated with tissue loss in the left perisylvian cortex, while card-sorting tasks with the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Huey et al., 2009). Set shifting tasks such as trails-making correlated with tissue loss in prefrontal and posterior parietal regions (Pa et al., 2010). Patients with bvFTD usually have relatively spared performances on verbal and visual memory tasks as well as visuospatial tasks.

With new emerging neuroimaging techniques, it is proposed that neurodegenerative diseases may involve various regions of the brain that operate together and are collectively referred to as brain networks. For example, the default mode network, including the posterior cingulate, medial temporal, lateral temporoparietal, and dorsal medial prefrontal regions, is thought to be involved in Alzheimer’s disease (Greicius et al., 2003; Buckner et al., 2005). Seeley and colleagues have shown prominent deficits in functional connectivity in other networks such as the salience using task free functional MRI and this promising technique is likely to become standard in the assessment of patients with bvFTD (Seeley et al., 2009 (2009); Seeley et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2010).

FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA AND MOTOR NEURON DISEASE

The co-association of FTD and ALS is now accepted at a clinical, neuropathological, and genetic level (Caselli et al., 1993; Lomen-Hoerth et al., 2002; Neary et al., 1990; Neary et al., 2000). Patients with frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease (FTD-MND) have the typical features of bvFTD that are either preceded or shortly followed by typical features of ALS. Perhaps one of the features that should make the clinician suspicious of MND with bvFTD is the lack of weight gain that classically comes with hyperorality, but instead, there is loss of weight resulting from muscle atrophy and diminished desire to swallow. Also, patients with FTD-MND have the highest frequency of concomitant psychotic symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations, which are less common in more classical forms of bvFTD. Familial FTD-MND was found to correlate with a genetic mutation on chromosome 9 and, in recent years, the culprit gene, C9ORF72, was discovered (see next section).

BEHAVIORAL VARIANT OF FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA “PHENOCOPY”

After the publication of diagnostic criteria for bvFTD, a group of patients was identified that fulfilled the criteria without necessarily progressing to a clinically defined dementia state, frequently plateauing at mild stages of the disease (Davies et al., 2006). These patients are referred to as bvFTD “phenocopies” because they display the “phenotype” of the disease, presumably without evidence of an underlying neurodegenerative process. These patients also score better on measures of activities of daily living as compared to patients with bvFTD (Mioshi et al., 2009). On neuropsychology testing, executive functions that are usually impaired in bvFTD may be spared in patients with the phenocopy (Hornberger et al., 2008). Magnetic resonance imaging is usually normal and does not reveal the typical pattern of frontal lobe atrophy seen in patients with the progressive type (Davies et al., 2006; Kipps et al., 2007). Further functional imaging with fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) displays no hypometabolism in frontal brain regions (Kipps et al., 2009). Patients with the phenocopy often have a much longer survival and seldom get institutionalized, as opposed to their progressive counterparts who usually advance to death or institutionalization within three to four years (Davies et al., 2006; Garcin et al., 2009). Few of these cases that have come to autopsy have been reported in the literature as lacking the pathological changes typically seen in FTLD (Kertesz et al., 2005), however, there is not yet a large number of autopsies to definitively classify these patients as lacking a clear neurodegenerative process.

Recently the discovery of the C9ORF72 gene as implicated in the pathogenesis of FTD led to some re-examination of patients previously labeled as phenocopy. It was found that two out of four patients with the bvFTD phenocopy diagnosis harbored the mutation, raising concerns that there might in fact be an underlying neurodegenerative process in at least a subset of these slowly progressive patients (Khan, Yokoyama et al., 2012b).

PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA

Primary progressive aphasia should be diagnosed when a patient experiences a progressive decline in language in which other cognitive domains and behavior are relatively spared for two years (Mesulam, 1982). The hallmark of the PPAs is a predominant deficit in conversational skills and language with an initial relative sparing of other cognitive and behavioral domains such as memory, executive functions, and visuospatial skills (Mesulam, 1982, 2001). Care must be taken when assessing other cognitive domains in a patient who has a primary language deficit because language greatly influences virtually all other cognitive functions. As an example, a person who does not understand the meaning of words may have difficulty memorizing them on verbal learning tasks.

Initial studies found that a primary language deficit can be the presenting clinical syndrome of many underlying brain pathologies, including FTLD, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and Alzheimer’s disease (Galton et al., 2000; Kertesz et al., 2000; Neary et al., 1998). In the past decade, a clearer understanding of primary language disorders divided their clinical presentation into three primary subtypes, each with a different clinical presentation and a distinct focal neuroanatomical correlate (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Each subtype also provides clues for the prediction of the underlying pathological neurodegenerative process. The classification criteria for PPA set forth by an international group of PPA investigators are summarized in Table 67.2 (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011).

NON-FLUENT VARIANT OF PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA

Non-fluent variant of primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA) is characterized by difficulties in speech production including agrammatism, an effortful, slow speech and/or apraxia of speech, defined as presence of speech initiation difficulties, sound distortion or substitution, and deletion or transposition of syllables (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Hodges and Patterson, 1996; Neary et al., 1998). This can be apparent in spontaneous speech or when patients are given a polysyllabic word to say multiple times in a row. Phonemic paraphasias such as faulty syllable sequencing (amadant for adamant) or improper usage of phoneme (bumble for mumble) can occur. Patients are usually aware of their deficits and may try to correct their pronunciation errors, which often leads to frustration.

In addition to these deficits in language production, difficulty in understanding complex sentences with difficult grammatical syntax may indicate agrammatism in comprehension. Single-word comprehension is typically preserved and patients with nvfPPA perform within normal limits on word comprehension tasks (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Patients with nfvPPA are the most likely to have motor findings on their neurological examination consisting of rigidity, and slowing and reduced dexterity, usually observable in the right arm (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Brain atrophy is mostly localized to the left perisylvian region, and more specifically to the pars opercularis and pars triangularis (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). The clinical presentation of nfvPPA usually points to an underlying pathology of CBD or TDP-43 type A (see the following).

Semantic Variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia

The semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) (see Case 2 later in chapter) was initially described in its left predominant form, which presents with a loss of knowledge of words and objects in the setting of a relatively preserved speech production (fluent speech) and grammar both in production and comprehension (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Hodges et al., 1992). Surface dyslexia can occur and is defined as the inability to recognize (and correctly read) irregular words, sounding them out instead. For example, a patient with surface dyslexia might read choir as chore. Similarly, spelling errors resulting from the inability to recognize words also occurs: in a word such as orchestra, the “ch” is pronounced and yacht is spelled like “yat.’” Patients with svPPA perform poorly on confrontation naming and word recognition tasks. In fact, their speech often contains non-specific words such as thing or animal to circumvent words that they have lost the meaning of (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Conversational speech is usually comprehended, although patients may ask about the meaning of a specific word in conversation. Patients with svPPA usually exhibit no motor findings on their neurological examination (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004).

Patients with svPPA often develop more behavioral changes in the course of their disease than do those with other subtypes of PPA (Rosen et al., 2006). Prominent features of these behavioral manifestations include loss of empathy, irritability, mental rigidity, and compulsive behavior, as well as disruption of sleep, appetite, and libido, likely speaking for the role of the anterior temporal lobe and the orbital frontal cortex (where svPPA quickly spreads to) in the manifestation of these symptoms. When the predominant presentation is behavioral, then the syndrome is that of right-sided predominant svPPA. In a longitudinal study of patients with either the right or left predominant svPPA, it was found that the disease spread to the contralateral temporal lobe within three years so that patients with initial language problems develop the behavioral disturbances later on and vice versa (Seeley et al., 2005). Both progressed to a more frontal type of behavioral disturbance within seven years.

Brain atrophy in svPPA localizes to the anterior temporal lobes bilaterally and can involve both lateral and medial aspects of the temporal lobe, including the inferior, middle, and superior temporal gyrus (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). The clinical presentation of svPPA strongly indicates an underlying pathology of TDP-43 type C.

LOGOPENIC VARIANT OF PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA

Patients with the logopenic variant of PPA (lvPPA) have a deficit in phonological memory, often erroneously termed echoic memory. Phonological memory allows a person to hold short-term information by “repeating” and “hearing” it in his or her mind, such as when given a phone number to dial. Patients with lvPPA have a slow and syntactically simple speech with many word-finding difficulties. They have difficulties repeating and comprehending long sentences, regardless of their syntactic difficulties. Patients with lvPPA can have difficulty with calculation and with memory tasks (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Brain atrophy localizes to the angular gyrus and posterior aspects of the middle temporal gyrus (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). The underlying pathology of lvPPA appears to be that of plaques and tangles similar to that seen in classical Alzheimer’s disease (Alladi et al., 2007; Josephs et al., 2008). Also, neuroimaging using Pittsburgh compound-B PET demonstrated that these patients have an amyloid deposition pattern similar to that seen in classical Alzheimer’s disease (Rabinovici et al., 2008 (2008)). In fact, lvPPA is now considered another “atypical” presentation of the more classically memory-predominant presentation of Alzheimer’s disease.

CORTICOBASAL SYNDROME

Corticobasal syndrome (CBS) is clinically characterized by asymmetrical basal ganglia symptoms manifesting as parkinsonism, rigidity, akinesia, tremor; and cortical symptoms manifesting as apraxia, myoclonus, cortical sensory loss, and alien limb (Gibb, Luthert, & Marsden, 1989b; Kompoliti et al., 1998; Boeve et al., 2003). The clinical syndrome and the pathological diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration (CBD, discussed in the following) were used interchangeably for decades. Yet, CBS and CBD are two distinct entities. Corticobasal degeneration, a neuropathologically defined entity, a four-repeat tauopathy with distinctive cortical and subcortical tau aggregates has variable clinical presentations; and, CBS, a clinical syndrome, is associated with a wide spectrum of underlying pathologies (AD, CBD, PSP, or TDP-43) (Lee et al., 2011). The clinical presentation of patients with CBD pathology is variable but includes nfvPPA, bvFTD, and an executive motor disorder with prominent difficulties with gait. Patients who initially present with clinical bvFTD and are found to have CBD pathology on autopsy tend to be more apathetic than have florid disinhibition, are more anxious, and have a more dorsal and milder pattern of frontal atrophy when compared with patients with bvFTD who end up having a pathology of Pick disease (Rankin et al., 2011).

PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY

Progressive supranuclear palsy is a neurodegenerative disorder that is pathologically defined by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads in brainstem, basal ganglia, and cerebellar nuclei associated with abnormal four repeat tau protein deposition (Hauw et al., 1994). The most common clinical presentation is that of Richardson syndrome and includes postural instability, gait imbalance, multiple falls, and supranuclear gaze palsy that primarily affects vertical saccades. However, around 5% of patients may present with a behavioral syndrome similar to that of bvFTD without any sign of parkinsonism, falls, or eye movement abnormality until much later in the disease (Hassan et al., 2011; Josephs et al., 2011). These signs should be examined carefully in patients presenting with bvFTD because they may point to the diagnosis of PSP. Vertical saccade abnormalities in particular have been found to have a high predictability of PSP pathology (Boxer et al., 2012). Magnetic resonance imaging might reveal only mild frontotemporal atrophy with or without the classical decrease in midbrain size.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is pivotal in reaching a more objective and neuroanatomically guided diagnosis in FTD. Patients with bvFTD usually have bilateral frontal and temporal atrophy with the earliest changes apparent in frontoinsular structures and other regions of the salient network (Seeley et al., 2009 (2009), 2012; Suarez et al., 2009). Nearly all patients referred with bvFTD show prominent frontally predominant atrophy, a finding that is often ignored in reports from radiologists (Suarez et al., 2009). Non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia shows atrophy in the left perisylvian region, whereas svPPA shows parenchymal volume loss in left (or right) anterior temporal lobe (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004). Patients with CBS show asymmetrical peri-rolandic dorsal atrophy, whereas those with PSP may show midbrain atrophy and a “hummingbird” sign on sagittal T1 resulting from atrophy of the midbrain tegmentum with a relative preservation of the pons (Massey et al., 2012).

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-

PET) may help in confirming a diagnosis of FTD. In a pathology-confirmed study, FDG-PET was found to be reliable among different raters and aid in the differentiation between FTD and AD pathology (Womack et al., 2011). In FTD, it shows hypometabolism of frontal, anterior cingulate, and anterior temporal regions, whereas hypometabolism of temporoparietal and posterior cingulate regions was observed in AD (Foster et al., 2007; Poljansky et al., 2011). With the advent of biomarkers such as Pittsburgh Compound-B PET for the detection of amyloidosis in the brain, it is imperative to recognize that co-pathologies can occur and the pathologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease should not be conclusive in patients with a positive PiB-PET and an otherwise clinical presentation of FTD (Caso, Gesierich et al., 2012).

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAM

Electroencephalograms (EEG) may help distinguish FTD from AD, especially when using quantitative analysis and other computational methods (Caso et al., 2012; Lindau et al., 2003; Yener et al., 1996). Yet, EEG is not used in the routine diagnosis of FTD.

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID MARKERS

Measurement of tau and amyloid-β42 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with neurodegenerative diseases is helpful in differentiating FTD from AD. In AD, amyloid-β42 levels are low with tau levels being elevated. In FTD, the ratio of tau/amyloid-β42 is significantly lower than in AD because of preserved amyloid-β42 levels. Using a cutoff of 1.06, the tau/amyloid-β42 ratio has a 79% sensitivity and a 97% specificity in discriminating between the two neurodegenerative conditions (Bian et al., 2008); however, this finding has not been validated in neuropathology-confirmed series. Measurements of other biomarkers in CSF continue to be investigated, especially for the differentiation of different pathological subtypes of FTD such as FTD-TDP43 and FTD-tau (see the following) (Zhu et al., 2010).

HISTOPATHOLOGY

The major pathological hallmark of FTLD is atrophy of the frontal and anterior temporal lobes with microvacuolation and astrogliosis observed in affected areas on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In early pathological studies, cases that lacked the Pick disease pathology were roughly 80% and formed a group of unknown pathological etiologies that did not have typical Alzheimer’s disease pathology. This group was initially termed frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type.

Over the past two decades, neuropathologists have deciphered many distinct histopathologies that can underlie a pathological diagnosis of what is now referred to as frontotemporal lobar degeneration. These can be broadly classified according to the predominant abnormal protein deposition found on immunohistochemistry, and more specifically categorized according to the pattern of protein deposition. The two major proteins with which FTLD is associated are tau (FTLD-tau) and TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43; FTLD-TDP).

TAU

3-R TAU

The term Pick disease now refers to an FTLD pathology with observable Pick bodies that consist of intraneuronal argyrophilic inclusions. Pick bodies are mainly composed of abnormal three-repeat tau protein aggregates and stain strongly with antibodies against the tau protein on immunohistochemistry. In pathological series, Pick disease is found in roughly 15% to 20% of patients with FTD (Brun, 1987; Rosso et al., 2003).

4-R TAU

Corticobasal degeneration was initially described as a Pick-like pathology of corticodentatonigral degeneration with neuronal achromasia (Rebeiz et al., 1967). Later, its specific histopathology was described as ballooned neurons, neuronal loss, astrocytosis, and tau-positive neuronal and glial inclusions with the presence of coiled bodies and axonal and dendritic threads consisting of four-repeat tau protein isoforms (Gibb et al., 1989a; Gibb et al., 1990; Komori, 1999; Houlden et al., 2001), associated with an H1/H1 haplotype (Houlden et al., 2001). Progressive supranuclear palsy is another pathology related to four-repeat tau protein depositions and is summarized in the preceding.

TDP-43

One of the major non–tau-related pathologies of FTLD was initially termed FTLD-U for the presence of ubiquitin. In the past decade, pathological studies uncovered the implication of a protein called TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) as one of the major pathologies in FTLD-U (for ubiquitin) and FTD-MND (Neumann et al., 2006).

Three distinct histological patterns of FTLD with TDP-43 pathology were recognized based on the morphology and anatomical distribution of neuronal inclusions (Mackenzie et al., 2006; Sampathu et al., 2006). A unified classification was proposed in 2011 and another category was added based on emerging studies (Mackenzie et al., 2011). Each of the four subtypes was found to correlate well with different clinical and genetic forms of FTD. FTLD-TDP 43 type A consists of many neuro-cytoplasmic inclusions (NCI) and short dystrophic neuritis (DN) predominantly in layer 2 of the cortex, and correlates mostly with the clinical syndrome of bvFTD and PNFA, especially in GRN mutation cases. FTLD-TDP 43 type B consists mostly of moderate NCI and only few DN found in all layers of the cortex, and correlates mostly with bvFTD and FTD-MND, especially linked to C9orf72 mutation cases. FTLD-TDP 43 type C consists mostly of numerous long DN and only few NCI predominantly in layer 2 of the cortex, and correlates best with svPPA. Finally, FTLD-TDP 43 type D consists of many lentiform neuronal intranuclear inclusions and many short DN in all layers of the cortex, and correlates best with the familial syndrome of inclusion body myopathy with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia, which is associated with mutations in the valosin-containing protein gene. Because different pathologies and genetic factors might invoke different treatment options in the future, it is important to recognize the diversity of these pathologies and the clinical clues that allow a differentiation between them.

FUS

A small number of patients with FTD have a pathology that stains positive with ubiquitin antibodies but lack a TDP-43 (or tau) pathology. These were found to have fused in sarcoma (FUS) protein (Neumann et al., 2009), which was later found to be the underlying pathology in 5% to 10% of patients presenting with bvFTD (Seelaar et al., 2008; Urwin et al., 2010). Patients with the FTLD-FUS pathology present with a severe behavioral syndrome at a younger age, with a mean of 41 years old, accompanied by a high prevalence of psychotic symptoms and very little motor symptoms until much later in the disease (Urwin et al., 2010).

GENETICS

The genetics of FTD was a focus of interest in the past decade. Although roughly 40% of the cases have a family history, around 10% have an autosomal dominant pattern of genetic heritability (Rohrer et al., 2009). The bvFTD group has the largest proportion of familial cases while svPPA has the least.

MAPT

The microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT), located on chromosome 17, was identified in 1998 as a culprit for a subset of familial Pick disease then termed FTD and parkinsonism (Hutton et al., 1998). The gene was found to carry a mutation in 17.8% of patients with clinically determined FTD and 43% of those with a positive family history in the Netherlands (Rizzu et al., 1999). In other series, it was found in 32% of patients with FTD and a positive family history, whereas only rare in the absence of family history (Rosso et al., 2003). In more recent case series mutations in MAPT was found in roughly 3% to 14% of patients with FTD (Rohrer et al., 2009; Seelaar et al., 2008). In our series it accounts for approximately 17% of all our familial forms of FTD.

These patients tend to have symmetrical frontal and anterior temporal atrophy; therefore, bvFTD is the most common clinical presentation (Rohrer et al., 2009). The typical age at the time of presentation is around 50 years, although patients have been seen with much earlier and later years of onset. Gene carriers were found to exhibit alteration of the functional connectivity in the default mode network (DMN) similar to that seen in patients with bvFTD who are also carriers of the mutation. This finding, in the absence of clinical symptoms or evidence of atrophy on structural imaging, suggests that a change in functional connectivity may be an early sign of the disease (Whitwell et al., 2011).

GRN

Mutations in the progranulin gene (PGRN), also located on chromosome 17, vary in frequency and are found in 1% to 16% of patients with FTD (Rohrer et al., 2009). They account for approximately 8% of all of our familial forms of FTD. The mean age of onset in patients with a GRN mutation is usually higher than that of patients with an MAPT mutation averaging around 62 years of age (Seelaar et al., 2008). Most of the GRN mutations cause nonsense-mediated decay of granulin so that no protein is produced by one chromosome. This is called haploinsufficiency, and patients with the mutation produce approximately 50% of the normal levels of progranulin (Rademakers et al., 2007).

Patients with GRN mutations tend to have an asymmetrical neurodegenerative condition that begins in the frontal or temporal region and spreads out along one hemisphere. Many are diagnosed with bvFTD or nfvPPA, whereas others are suspected of having CBS or Alzheimer’s disease because of the spread into posterior brain regions. Additionally, the parkinsonian features found in some individuals lead them to be diagnosed with Parkinson disease.

Studies in knockout rat hippocampal cultures show that low progranulin levels reduce neural connectivity by decreasing the number of synapses and length of axons (Tapia et al., 2011). Interestingly, the number of neuronal vesicles per synapse was increased, similarly to observations in brains of patients with FTD and harboring the GRN mutation. The whole progranulin molecule seems to work as a neuronal growth factor that works at the neuronal level via the sortilin receptor, whereas it is broken down into smaller granulins molecules that activate inflammation. Histone deacetylase inhibitors increase the production of progranulin from the normal chromosome offering hope for a therapy for FTD related to this mutation.

C9ORF72

In the past two decades, several families with FTD-MND were reported, the genetic culprit being an autosomal dominant mutation that linked to a locus on chromosome 9. In 2011, a noncoding GGGGCC hexanucleotide expansion in the gene called C9orf72 was described and found to be strongly associated with the disease (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). It became the most common genetic mutation in familial FTD (11.7% of cases) and familial ALS (23.5% of cases). The expansion was found in 7% of Caucasians with sporadic ALS and 39.3% of Caucasians with familial ALS. In FTD, the expansion is found in 6% of individuals of European ancestry in the sporadic form and 24.8% in the familial form. It accounts for approximately two-thirds of our familial cases of FTD. Data for non-Caucasian ethnic groups is scarce but it has been reported in Asians. The mutation was found to have very strong penetrance with the typical age of onset in the sixth decade (Majounie et al., 2012).

Clinically, patients with the C9 mutation often present similarly to patients with sporadic bvFTD. In our series we found a higher prevalence of delusions in C9 carriers (approximately 21%) compared with patients with sporadic bvFTD (approximately 10%) (Sha et al., 2012). Measurements of gray matter atrophy by voxel-based morphometry analysis of MRI images of 76 subjects with bvFTD revealed differences in brain parenchymal volume loss across subjects with different genetic mutations: symmetric atrophy in dorsolateral, medial orbitofrontal, anterior temporal, parietal, occipital, and cerebellar regions was associated with mutations in the C9orf72, whereas anteromedial temporal atrophy was associated with mutations in the MAPT gene and temporoparietal atrophy with mutations in the progranulin gene (Whitwell et al., 2012).

TREATMENT

The treatment for FTD is complex and calls for a multidisciplinary approach. Perhaps the first approach for treatment focuses on the education of patients and their caregivers (Merrilees, 2007). The understanding that abnormal behavior stems from a brain dysfunction can be difficult to grasp and caregivers may become quickly tired and frustrated. It is crucial for caregivers to develop strategies to help effectively interact with patients suffering from FTD and to keep them safe from the faulty judgment that inherently accompanies their disease (Perry and Miller, 2001). Social support services including support groups, home health aides, and a day care center can provide a healthy environment in which patients with FTD, especially in more advanced stages, can continue to have a good quality of life, especially in the absence of more structured institutions and nursing homes to care for a young population with a dementing illness (Chemali et al., 2010; Chemali et al., 2012).

The pharmacological treatment of FTD can be divided into symptomatic or disease-modifying therapy. Disease-modifying treatments would ideally target the underlying molecule associated with the respective pathology. For that reason, specific clinicopathological correlations are important to differentiate among diseases that would respond to a specific disease-modifying agent. For example, if a drug were to target TDP-43 pathology, it would be crucial to differentiate between cases of bvFTD that have TDP-43 as their underlying pathology as opposed to tau. Such treatments are currently not available. The results of a large multicenter clinical trial of PSP (a tauopathy) with davunetide, a microtubule stabilizing small peptide, were reported in December of 2012. The study failed to detect an effect on primary outcome measures. Similarly, a trial for patients with progranulin mutations is contemplated for 2013.

Because FTD is associated with many aberrant behaviors that might be troublesome to patients, their caregivers, and their surroundings, symptomatic therapy, although not curative, is important for a healthy patient–caregiver dynamic. It also provides control to patients that might be considered disruptive to others, especially in assisted living and nursing home settings. Both selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antipsychotic medications have been used in the symptomatic treatment of FTD. Indeed, autopsy and imaging studies seem to suggest that there is a serotonergic deficit in patients with FTD, possibly related to the neural projections from the raphe nuclei to the frontal cortex (Huey et al., 2006). There are also PET and SPECT studies that implicate deficiencies in the dopaminergic systems, especially in the striatum, in FTD (Huey et al., 2006).

From the SSRIs, paroxetine (Paxil©) was the most studied in FTD. It was shown to improve behavior symptoms such as disinhibition and compulsions at a dose of 20 mg per day (Kerchner et al., 2011); however, because of its anticholinergic effect, paroxetine may worsen cognitive symptoms (Deakin et al., 2004). On the other hand, citalopram (Celexa©) has very little anticholinergic effect and had been successfully used in the treatment of behavioral symptoms in AD patients (Pollock et al., 2002). It was also shown to decrease behavioral symptoms in patients with FTD at a dose of 30 mg daily (Herrmann et al., 2011). Trazodone at a dose of 150 to 300 mg daily also helps control agitation and eating disorders in patients with FTD (Lebert et al., 2004). Antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine and risperidone have been used in the treatment of agitation and disinhibition in FTD. However, there is little evidence-based support for their use and the high risk of extrapyramidal symptoms argues against their use (Kerchner et al., 2011).

CASE 1

Mr. X is a 73-year-old right-handed man who presented to the clinic with his daughter and his fiancée. He was at baseline an accomplished man, holding a PhD in sociology and working in an academic setting until retirement. His ex-wife was a biology professor and had been deceased for more than 15 years. He met his current fiancée eight years ago after flirtatiously following her into a restaurant. His daughter describes him previously as a sophisticated man. She feels that at baseline her father was gregarious and outgoing, while being respectful.

Four years ago, Mr. X started making rude remarks to friends and strangers who attended his weekly movie night. In fact, he ended a friendship with a long-term woman after insulting her and calling her derogatory names in front of other guests. His social decorum declined since and his daughter describes him now as having “no filter,” telling people rude remarks to their faces. During the renewal of his driving license one year ago, he quarreled with his examiner and failed the test. He has also been walking up to strangers, starting conversations and touching them inappropriately; for example, hugging them. Furthermore, he is losing interest in activities he usually enjoyed doing such as fishing. He does not enjoy movies anymore but watches TV shows. His symptoms have all been slowly progressive over time.

Mr. X has lost the ability to be empathic and attentive to other people’s needs and emotions. Once, his fiancée was having a bout of diverticulitis with severe vomiting and he simply told her that he will be waiting for her in the car to go visit his daughter. He has become more self-centered and cares less about others’ needs.

His daughter also describes ritualistic behavior. For example, he enjoys saluting the sun and the moon. When he walks through a room, he high-fives the walls, the tables, and the chairs that are on his way, sometimes kissing the back of the chairs. His attention to grooming has diminished and he now wears the same clothes over and over again until they are worn down. He uses the bathroom frequently during the day without necessarily urinating. Moreover, he compulsively sticks his tongue out. He often repeats catch phrases as well as tunes that he sings or whistles constantly regardless of the social setting. He is described as impulsive. In addition, he has been having paranoid delusions for the past three years. He checks that all the doors are locked and there are no people hiding under the beds.

Regarding his eating behavior, at the onset of the disease he had a decreased appetite and lost some weight. He had decreased interest in the gourmet food he usually enjoyed. He started craving sweets and could eat candy all day. In addition, he was drinking more and smoking cigars.

In terms of memory complaints, Mr. X often asked the same question repeatedly. He forgot plans and errands. In terms of executive functions, he had difficulties with planning and organization, multi-tasking, concentration, judgment, and problem-solving. His fiancée in fact does all the finances and sorts his mail. His language and visuospatial domains were spared.

Mr. X does not report any memory, cognitive, or behavioral complaints when asked.

He has no pertinent family history except for alcoholism in his father and a non-specific behavioral syndrome in his paternal uncle with onset at 40 years old. His grandfather was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

On physical examination, Mr. X was wearing a green sweater, worn-out jeans, and tennis shoes. His behavior was childish and he giggled throughout the exam. He asked to leave the room multiple times to use the bathroom. He stuck out his tongue multiple times at the examiner. His neurological examination was essentially normal except for a mild increase in tone of his left arm. On his neuropsychology testing, he had difficulties with tasks of verbal and visual memory, as well as a decreased performance on design fluency with relative sparing of other domains.

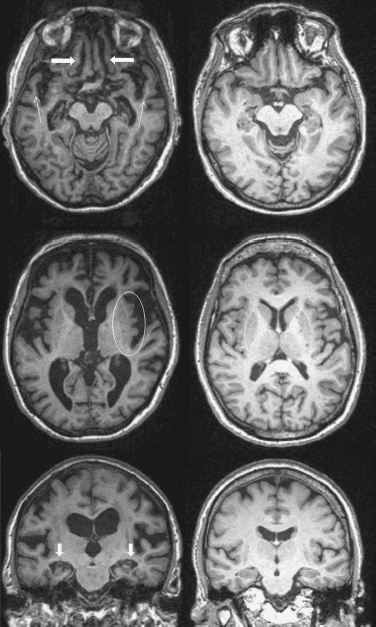

His MRI revealed bilateral orbitofrontal, bilateral insular, bilateral caudate, bilateral anterior temporal, and bilateral hippocampal volume loss, with generally worse parenchymal loss on the right than on the left (Fig. 67.1).

This case illustrates the typical presentation of a patient with bvFTD. Mr. X fulfills five out of the six criteria for the clinical diagnosis of bvFTD (see Table 67.2) with the exception of executive deficits on neuropsychology testing, possibly because of sparing of the dorsolateral structures. This case also demonstrates that patients with classical bvFTD can also have memory impairments and that the presence of short-term memory loss should not preclude the diagnosis.

Figure 67.1 Mr. X magnetic resonance image (MRI) (left) as compared with a normal control (right) shows bilateral orbitofrontal (thick arrows) and anterior temporal (thin arrows) parenchymal volume loss (top images), bilateral insular volume loss (oval, middle images), and bilateral hippocampal volume loss (arrows, bottom images). In this figure, all sequences are T1-weighted and the right side of the MRI images corresponds to the right hemisphere.

CASE 2

Ms. Y is a 50-year-old right-handed woman who presented to the clinic with a chief complaint of “forgetting words and names,” which started five years ago. This was first noticeable when she was reading stories to her two-year-old boy and she could not come up with the names of animals depicted in the story books, such as “rabbit” or “squirrel.” She initially was able to describe the words she could not come up with, but became worse over time. For example, she would say “the word that starts with H and that pushes things against the wall as opposed to screwing.” She also had difficulties recalling names of famous actors and names of cities. Moreover, she often asked about the meaning of words but had no difficulties comprehending and participating in general conversations.

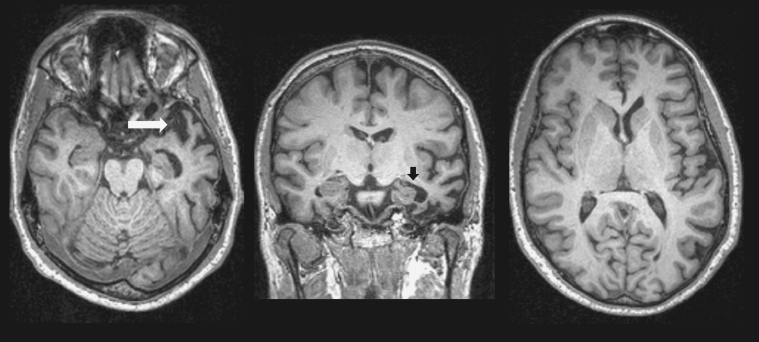

Figure 67.2 Ms. Y’s MRI reveals left anterior temporal lobe volume loss in axial (right) and coronal (middle) planes on T1 sequences (arrows). There is relative preservation of other brain structures (left).

She had no memory, executive function, visuospatial, motor, or behavioral complaints. She continued to be independent in her activities of daily living. Her family history was unremarkable.

On exam, Ms. Y was appropriately groomed. Her speech output was increased, fluent, and grammatically intact, with word-finding difficulties and frequent questioning of the meaning of words. She had difficulties naming objects around the room. She spelled “cough” as “coff,” “knot” as “naught” or “note,” “choir” as “cwier,” and she could not spell “yacht.” She named only four out of 15 items on a naming test and could point to the correct picture describing a word in five out of 16 cases. Her visuospatial and executive functions skills were intact. She has mild difficulties on verbal learning tasks likely confounded by her inability to understand the meaning of the words. She performed well on visual memory tasks. Her neurological examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Her MRI is shown in Figure 67.2 and reveals left anterior temporal lobe parenchymal volume loss with relative preservations of other brain structures. There is only a slight volume loss in the right anterior temporal lobe.

This case illustrates the typical presentation of svPPA. The history and exam are usually focally localizing to the anterior temporal lobe through a predominant deficit of loss of word and object knowledge. Behavioral disturbances arise when more right anterior temporal lobe structures become involved. The underlying pathology is almost always that of TDP-43. Notice that in most cases the family history is unremarkable as this is the least genetic related disorder of all FTDs.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Naasan has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. Miller receives grant support from the NIH/NIA and has nothing to disclose related to this chapter. Dr. Miller serves as a consultant for TauRx, Allon Therapeutics and Siemens Medical Solutions. He has also received a research grant from Novartis. He is on the board of directors for the John Douglas French Foundation for Alzheimer’s Research and for The Larry L. Hillblom Foundation.

REFERENCES

Alladi, S., Xuereb, J., et al. (2007). Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 130(Pt 10):2636–2645.

Bian, H., Van Swieten, J.C., et al. (2008). CSF biomarkers in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with known pathology. Neurology 70(19 Pt 2):1827–1835.

Boeve, B.F., Lang, A.E., et al. (2003). Corticobasal degeneration and its relationship to progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 54(Suppl 5):S15–19.

Boxer, A.L., Garbutt, S., et al. (2012). Saccade abnormalities in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 69(4):509–517.

Brun, A. (1987). Frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type: I. neuropathology. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 6(3):193–208.

Brunnstrom, H., Gustafson, et al. (2009). Prevalence of dementia subtypes: A 30-year retrospective survey of neuropathological reports. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 49(1):146–149.

Buckner, R.L., Snyder, A.Z., et al. (2005). Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J. Neurosci. 25(34):7709–7717.

Cairns, N.J., Bigio, E.H., et al. (2007). Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the consortium for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 114(1):5–22.

Caselli, R.J., Windebank, A.J., et al. (1993). Rapidly progressive aphasic dementia and motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 33(2):200–207.

Caso, F., Cursi, M., et al. (2012). Quantitative EEG and LORETA: valuable tools in discerning FTD from AD? Neurobiol. Aging 33(10):2343–2356.

Caso, F., Gesierich, B., et al. (2012). Nonfluent/agrammatic PPA with in-vivo cortical amyloidosis and pick’s disease pathology. Behav. Neurol. 26(1–2):95–106.

Chemali, Z., Schamber, S., et al. (2012). Diagnosing early onset dementia and then what? A frustrating system of aftercare resources. Int. J. Gen. Med. 5:81–86.

Chemali, Z., Withall, A., et al. (2010). The plight of caring for young patients with frontotemporal dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 25(2):109–115.

Chow, T.W., Miller, B.L., et al. (1999). Inheritance of frontotemporal dementia. Arch. Neurol. 56(7):817–822.

Davies, R.R., Kipps, C.M., et al. (2006). Progression in frontotemporal dementia: identifying a benign behavioral variant by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch. Neurol. 63(11):1627–1631.

Deakin, J.B., Rahman, S., et al. (2004). Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacol. 172(4):400–408.

DeJesus-Hernandez, M., Mackenzie, I.R., et al. (2011). Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72(2):245–256.

Eslinger, P.J., Moore, P., et al. (2012). Apathy in frontotemporal dementia: behavioral and neuroimaging correlates. Behav. Neurol. 25(2):127–136.

Foster, N.L., Heidebrink, J.L., et al. (2007). FDG-PET improves accuracy in distinguishing frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 130(Pt 10):2616–2635.

Galton, C.J., Patterson, K., et al. (2000). Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain 123(Pt 3):484–498.

Garcin, B., Lillo, P., et al. (2009). Determinants of survival in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 73(20):1656–1661.

Gibb, W.R., Luthert, P.J., et al. (1990). Clinical and pathological features of corticobasal degeneration. Adv. Neurol. 53:51–54.

Gibb, W.R., Luthert, P.J., et al. (1989). Corticobasal degeneration. Brain 112(Pt 5):1171–1192.

Gislason, T.B., Sjogren, M., et al. (2003). The prevalence of frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and the frontal lobe syndrome in a population based sample of 85 year olds. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 74(7):867–871.

Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Dronkers, N.F., et al. (2004). Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 55(3):335–346.

Gorno-Tempini, M.L., Hillis, A.E., et al. (2011). Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76(11):1006–1014.

Greicius, M.D., Geschwind, M.D., et al. (2002). Presenile dementia syndromes: an update on taxonomy and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 72(6):691–700.

Greicius, M.D., Krasnow, B., et al. (2003). Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100(1):253–258.

Hassan, A., Parisi, J.E., et al. (2011). Autopsy-proven progressive supranuclear palsy presenting as behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase 18(6):478–488.

Hauw, J.J., Daniel, S.E., et al. (1994). Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology 44(11):2015–2019.

Herrmann, N., Black, S.E., et al. (2011). Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20(9):789–797.

Hodges, J.R., Davies, R.R., et al. (2004). Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 56(3):399–406.

Hodges, J.R., and Patterson, K. (1996). Nonfluent progressive aphasia and semantic dementia: a comparative neuropsychological study. JINS 2(6):511–524.

Hodges, J.R., Patterson, K., et al. (1992). Semantic dementia: progressive fluent aphasia with temporal lobe atrophy. Brain 115(Pt 6):1783–1806.

Hornberger, M., Geng, J., et al. (2011). Convergent grey and white matter evidence of orbitofrontal cortex changes related to disinhibition in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134(Pt 9):

2502–2512.

Hornberger, M., Piguet, O., et al. (2008). Executive function in progressive and nonprogressive behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 71(19):1481–1488.

Hou, C.E., Yaffe, K., et al. (2006). Frequency of dementia etiologies in four ethnic groups. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 22(1):42–47.

Houlden, H., Baker, M., et al. (2001). Corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy share a common tau haplotype. Neurology 56(12):1702–1706.

Hu, W.T., Chen-Plotkin, A., et al. (2010). Novel CSF biomarkers for frontotemporal lobar degenerations. Neurology 75(23):2079–2086.

Huey, E.D., Goveia, E.N., et al. (2009). Executive dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia and corticobasal syndrome. Neurology 72(5):453–459.

Huey, E.D., Putnam, K.T., et al. (2006). A systematic review of neurotransmitter deficits and treatments in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 66(1):17–22.

Hutton, M., Lendon, C.L., et al. (1998). Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393(6686):702–705.

Ikeda, M., Ishikawa, T., et al. (2004). Epidemiology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 17(4):265–268.

Johnson, J.K., Diehl, J., et al. (2005). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: demographic characteristics of 353 patients. Arch. Neurol. 62(6):925–930.

Josephs, K.A., Whitwell, J.L., et al. (2008). Progressive aphasia secondary to Alzheimer disease vs FTLD pathology. Neurology 70(1):25–34.

Josephs, K.A., Whitwell, J.L., et al. (2011). Gray matter correlates of behavioral severity in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov. Disord. 26(3):493–498.

Kerchner, G.A., Tartaglia, M.C., et al. (2011). Abhorring the vacuum: use of Alzheimer’s disease medications in frontotemporal dementia. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 11(5):709–717.

Kertesz, A., Martinez-Lage, P., et al. (2000). The corticobasal degeneration syndrome overlaps progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 55(9):1368–1375.

Kertesz, A., McMonagle, P., et al. (2005). The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 128(Pt 9):1996–2005.

Khan, B.K., Woolley, J.D., et al. (2012b). Schizophrenia or neurodegenerative disease prodrome? Outcome of a first psychotic episode in a 35-year-old woman. Psychosomatics 53(3):280–284.

Khan, B.K., Yokoyama, J.S., et al. (2012a). Atypical, slowly progressive behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia associated with C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 83(4):358–364.

Kipps, C.M., Hodges, J.R., et al. (2009). Combined magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography brain imaging in behavioural variant frontotemporal degeneration: refining the clinical phenotype. Brain 132(Pt 9):2566–2578.

Kipps, C.M., Nestor, P.J., et al. (2007). Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia: not all it seems? Neurocase 13(4):237–247.

Knopman, D.S., Petersen, R.C., et al. (2004). The incidence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in Rochester, Minnesota, 1990 through 1994. Neurology 62(3):506–508.

Komori, T. (1999). Tau-positive glial inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and pick’s disease. Brain Pathol. 9(4):663–679.

Kompoliti, K., Goetz, C.G., et al. (1998). Clinical presentation and pharmacological therapy in corticobasal degeneration. Arch. Neurol. 55(7):957–961.

Kramer, J.H., Jurik, J., et al. (2003). Distinctive neuropsychological patterns in frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, and Alzheimer disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 16(4):211–218.

Le Ber, I., Guedj, E., et al. (2006). Demographic, neurological and behavioural characteristics and brain perfusion SPECT in frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 129(Pt 11):3051–3065.

Lebert, F., Stekke, W., et al. (2004). Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 17(4):355–359.

Lee, S.E., Rabinovici, G.D., et al. (2011). Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 70(2):327–340.

Lindau, M., Jelic, V., et al. (2003). Quantitative EEG abnormalities and cognitive dysfunctions in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 15(2):106–114.

Lomen-Hoerth, C., Anderson, T., et al. (2002). The overlap of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 59(7):1077–1079.

Lund and Manchester Groups. (1994). Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 57(4):416–418.

Mackenzie, I.R., Baborie, A., et al. (2006). Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol. 112(5):539–549.

Mackenzie, I.R., Neumann, M., et al. (2011). A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 122(1):111–113.

Majounie, E., Renton, A.E., et al. (2012). Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 11(4):323–330.

Massey, L.A., Micallef, C., et al. (2012). Conventional magnetic resonance imaging in confirmed progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. Mov. Disord. 27(14):1754–1762.

Mercy, L., Hodges, J.R., et al. (2008). Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology 71(19):1496–1499.

Merrilees, J. (2007). A model for management of behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 21(4):S64–S69.

Merrilees, J., Dowling, G.A., et al. (2012). Characterization of apathy in persons wth frontotemporal dementia and the impact on family caregivers. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. [Epub ahead of print]

Mesulam, M.M. (1982). Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann. Neurol. 11(6):592–598.

Mesulam, M.M. (2001). Primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 49(4):425–432.

Miller, B.L., Cummings, J.L., et al. (1991). Frontal lobe degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological, and SPECT characteristics. Neurology 41(9):1374–1382.

Mioshi, E., Kipps, C.M., et al. (2009). Activities of daily living in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: differences in caregiver and performance-based assessments. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 23(1):70–76.

Neary, D., Snowden, J.S., et al. (1998). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51(6):1546–1554.

Neary, D., Snowden, J.S., et al. (2000). Cognitive change in motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MND/ALS). J. Neurol. Sci. 180(1–2):15–20.

Neary, D., Snowden, J.S., et al. (1990). Frontal lobe dementia and motor neuron disease. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 53(1):23–32.

Neumann, M., Rademakers, R., et al. (2009). A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain 132(Pt 11):2922–2931.

Neumann, M., Sampathu, D.M., et al. (2006). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314(5796):130–133.

Pa, J., Possin, K.L., et al. (2010). Gray matter correlates of set-shifting among neurodegenerative disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy older adults. JINS 16(4):640–650.

Papageorgiou, S.G., Kontaxis, T., et al. (2009). Frequency and causes of early-onset dementia in a tertiary referral center in athens. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 23(4):347–351.

Perry, R.J., and Miller, B.L. (2001). Behavior and treatment in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 56(11 Suppl 4):S46–51.

Peters, F., Perani, D., et al. (2006). Orbitofrontal dysfunction related to both apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 21(5–6):373–379.

Pick, A. (1892). Uber die beziehungen der senilen hirnatropie zur aphasie [Pertaining to senile brain-atrophy and aphasia]. Prag. Med. Wchnschr. 17:165–167.

Piguet, O., Petersen, A., et al. (2011). Eating and hypothalamus changes in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 69(2):

312–319.

Poljansky, S., Ibach, B., et al. (2011). A visual [18F]FDG-PET rating scale for the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 261(6):433–446.

Pollock, B.G., Mulsant, B.H., et al. (2002). Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 159(3):460–465.

Possin, K.L., Brambati, S.M., et al. (2009). Rule violation errors are associated with right lateral prefrontal cortex atrophy in neurodegenerative disease. JINS 15(3):354–364.

Rabinovici, G.D., Jagust, W.J., et al. (2008). Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 64(4):388–401.

Rademakers, R., Baker, M., et al. (2007). Phenotypic variability associated with progranulin haploinsufficiency in patients with the common 1477C→T (Arg493X) mutation: an international initiative. Lancet Neurol. 6(10):857–868.

Rankin, K.P., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., et al. (2006). Structural anatomy of empathy in neurodegenerative disease. Brain 129(Pt 11):2945–2956.

Rankin, K.P., Mayo, M.C., et al. (2011). Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with corticobasal degeneration pathology: phenotypic comparison to bvFTD with pick’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 45(3):594–608.

Rascovsky, K., Hodges, J.R., et al. (2011). Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 134(Pt 9):2456–2477.

Ratnavalli, E., Brayne, C., et al. (2002). The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 58(11):1615–1621.

Rebeiz, J.J., Kolodny, E.H., et al. (1967). Corticodentatonigral degeneration with neuronal achromasia: a progressive disorder of late adult life. T. Am. Neurol. Assoc. 92:23–26.

Renton, A.E., Majounie, E., et al. (2011). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72(2):257–268.

Rizzu, P., Van Swieten, J.C., et al. (1999). High prevalence of mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau in a population study of frontotemporal dementia in the Netherlands. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64(2):414–421.

Roberson, E.D., Hesse, J.H., et al. (2005). Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65(5):719–725.

Rohrer, J.D., Guerreiro, R., et al. (2009). The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 73(18):1451–1456.

Rosen, H.J., Allison, S.C., et al. (2005). Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain 128(Pt 11):2612–2625.

Rosen, H.J., Allison, S.C., et al. (2006). Behavioral features in semantic dementia vs other forms of progressive aphasias. Neurology 67(10):1752–1756.

Rosen, H.J., Wilson, M.R., et al. (2006). Neuroanatomical correlates of impaired recognition of emotion in dementia. Neuropsychologia 44(3):365–373.

Rosso, S.M., Donker Kaat, L., et al. (2003). Frontotemporal dementia in the Netherlands: patient characteristics and prevalence estimates from a population-based study. Brain 126(Pt 9):2016–2022.

Sampathu, D.M., Neumann, M., et al. (2006). Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 169(4):1343–1352.

Seelaar, H., Kamphorst, W., et al. (2008). Distinct genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 71(16):1220–1226.

Seeley, W.W., Bauer, A.M., et al. (2005). The natural history of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 64(8):1384–1390.

Seeley, W.W., Crawford, R.K., et al. (2009). Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron 62(1):42–52.

Seeley, W.W., Zhou, J., et al. (2012). Frontotemporal dementia: what can the behavioral variant teach us about human brain organization? Neuroscientist 18(4):373–385.

Sha, S.J., Takada, L.T., et al. (2012). Frontotemporal dementia due to C9ORF72 mutations: clinical and imaging features. Neurology 79(10):1002–1011.

Snowden, J.S., Bathgate, D., et al. (2001). Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Psychiatry 70(3):323–332.

Stevens, M., van Duijn, C.M., et al. (1998). Familial aggregation in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 50(6):1541–1545.

Suarez, J., Tartaglia, M.C., et al. (2009). Characterizing radiology reports in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 73(13):1073–1074.

Tapia, L., Milnerwood, A., et al. (2011). Progranulin deficiency decreases gross neural connectivity but enhances transmission at individual synapses. J. Neurosci. 31(31):11126–11132.

Urwin, H., Josephs, K.A., et al. (2010). FUS pathology defines the majority of tau- and TDP-43-negative frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 120(1):33–41.

van Swieten, J.C., and Heutink, P. (2008). Mutations in progranulin (GRN) within the spectrum of clinical and pathological phenotypes of frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 7(10):965–974.

Whitwell, J.L., Josephs, K.A., et al. (2011). Altered functional connectivity in asymptomatic MAPT subjects: a comparison to bvFTD. Neurology 77(9):866–874.

Whitwell, J.L., Weigand, S.D., et al. (2012). Neuroimaging signatures of frontotemporal dementia genetics: C9ORF72, tau, progranulin and sporadics. Brain 135(Pt 3):794–806.

Womack, K.B., Diaz-Arrastia, R., et al. (2011). Temporoparietal hypometabolism in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and associated imaging diagnostic errors. Arch. Neurol. 68(3):329–337.

Woolley, J.D., Gorno-Tempini, M.L., et al. (2007). Binge eating is associated with right orbitofrontal-insular-striatal atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 69(14):1424–1433.

Woolley, J.D., Khan, B.K., et al. (2011). The diagnostic challenge of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: rates of and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with early neurodegenerative disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72(2):126–133.

Yener, G.G., Leuchter, A.F., et al. (1996). Quantitative EEG in frontotemporal dementia. Clin. EEG 27(2):61–68.

Zamboni, G., Huey, E.D., et al. (2008). Apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia: insights into their neural correlates. Neurology 71(10):736–742.

Zhou, J., Greicius, M.D., et al. (2010). Divergent network connectivity changes in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and alzheimer’s disease. Brain 133(Pt 5):1352–1367.