59 | CLINICAL AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

JASON HASSENSTAB, JEFFREY BURNS, AND JOHN C. MORRIS

Alois Alzheimer reported in a meeting of German psychiatrists in 1906 his conclusion that a pathologic brain process, marked by microscopic lesions now recognized as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, was responsible for the dementia and psychosis experienced for years by a woman before she died at age 55. His report generated little enthusiasm or interest from the audience and for many years thereafter what became known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was considered to be an unusual presenile dementing disorder and garnered little attention. Studies in the 1960s, however, by Bernard Tomlinson, Gary Blessed, and Martin Roth in Great Britain (Tomlinson et al., 1968, 1970) showed conclusively that the neuropathology of the presenile disorder was identical to that of the far more numerous older cases of “senile dementia,” thus establishing that AD is the same clinicopathologic disorder regardless of its age at onset. Based on this knowledge, Robert Katzman in 1976 correctly presaged the rapidly increasing prevalence and malignancy of AD (Katzman, 1976).

Alzheimer’s disease is by far the most common cause of dementia and is present in 77% of demented individuals (Barker et al., 2002). It is strongly age-associated and thus typically is a disorder of older adulthood: 7% of persons affected by AD are age 65 to 74, 53% are 75 to 84, and 40% are 85 and older (Hebert et al., 2003). The prevalence of AD doubles every five years after the age of 65, affecting as many as 47% of people 85 years and older (Evans, 1987). Increased life expectancy in the United States and other developed countries has fueled an unprecedented growth in the elderly population that, in the absence of truly effective therapies, ensures continued dramatic increases in the prevalence of AD. In the United States alone, costs of caring for individuals with AD are estimated to be over $200 billion annually (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). Although these figures very likely are underestimates given that AD is considerably underrecognized in clinical practice (Lavery et al., 2007) and on death certificates (Wachterman et al., 2008), the number of cases of AD, currently estimated to be 5.3 million in the United States, are expected to nearly triple over the next 50 years (Hebert, 2001).

This chapter reviews the clinical and neuropsychological characteristics and course of dementia caused by AD with a focus on its earliest symptomatic stages, because the typical person affected by AD is not profoundly demented (48% of individuals affected by AD are mildly demented, 31% are moderately demented, and only 21% are severely demented [Hebert et al., 2003]). The chapter is written from the viewpoint of the clinician. It addresses the variability in current sets of clinical diagnostic criteria for AD and provides the rationale for the use of biological markers (biomarkers) to aid in moving the diagnostic process from a syndromic to a quantitative basis. Full discussions of biomarkers are found elsewhere in this section (imaging, Chapter 62; fluid, Chapter 63). Similarly, other illnesses that are considered in the differential diagnosis of AD dementia are addressed (dementia with Lewy bodies, Chapter 66; frontotemporal dementia, Chapter 67; vascular dementia, Chapter 68; prion disease, Chapter 69) and therapeutic approaches for AD dementia are the focus of Chapters 64 and 65. Genetic factors for AD are fully discussed in Chapter 60.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease is defined histopathologically by the presence of the hallmark lesions of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Plaques are composed of extracellular beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptide deposited in the cerebral cortex as amorphous aggregates (diffuse plaques) and those with degenerating dendrites that contain hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates (neuritic plaques). NFTs are intracellular fibrillar aggregates of the hyperphosphorylated form of the microtubule-associated protein tau. NFTs are not specific for AD, suggesting that they may represent a secondary response to neuronal injury, at least in some instances. On the other hand, there is a strong association of Aβ plaques with AD. Down Syndrome and autosomal dominantly inherited AD, caused by deterministic mutations (or duplications) in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) genes are rare but highly penetrant genetic causes of AD and are linked mechanistically by the overproduction of Aβ or an alteration in the ratio of the Aβ42 isoform to Aβ40. Hence, Aβ dysregulation (e.g., overproduction, reduced clearance, altered processing) is hypothesized as a critical “upstream” factor in the pathogenesis of AD (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). When AD dementia is present, however, NFTs correlate more strongly with cognitive dysfunction than do plaques, perhaps because NFTs are more associated with synaptic and neuronal injury. The full-blown AD process involves many other pathologic factors, including neuroinflammation, microglial activation, oxidative stress, and cell cycle abnormalities, that may contribute to disease progression. Although the precise cause(s) of AD remain unknown (Small and Duff, 2008), recent evidence of a gene mutation that results in inhibition of the proteolytic processing of APP into amyloidogenic peptides is associated with reduced incidence of cognitive decline and AD dementia in older adults, providing additional support for the amyloid hypothesis of AD (Jonsson et al., 2012).

Several sets of criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of AD, based on the recognition of plaques and NFTs, have been developed but emphasize slightly different facets, such as whether diffuse and neuritic plaques or only neuritic plaques are considered (Nelson et al., 2012). A consensus panel now has recommended standard guidelines for the neuropathological assessment of AD and for its clinicopathologic correlations (Hyman et al., 2012). These new guidelines recognize a preclinical stage of AD, wherein Aβ deposits appear to accumulate over many years as plaques in the cerebral cortex in the absence of symptoms (Price and Morris, 1999). This preclinical stage is hypothesized as a clinically silent pathologic cascade resulting in increasing synaptic and neuronal loss that eventually produces the symptomatic stage (Jack et al., 2010; Perrin et al., 2009). This hypothesis also suggests that attempts to treat individuals with symptomatic AD may require a combination of drugs that target the multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in the cascade. Because (presumably) irreversible neuronal loss already is substantial in medial temporal lobe structures by the time AD symptoms first appear (Price et al., 2001), detection of preclinical AD (before the brain is badly damaged) is desirable to enable possible “secondary prevention” strategies where therapeutic interventions aim to delay or possibly even prevent the appearance of symptomatic AD.

THE ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE CONTINUUM

Work groups convened by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association (AA) to revise clinical diagnostic criteria for symptomatic AD proposed a continuum that begins with the preclinical AD stage and then gradually manifests with subtle symptoms of mild cognitive impairment that then progresses to fully developed AD dementia. Compelling support for the AD continuum comes from a study of dominantly inherited AD. Representing less than 1% of all AD, individuals from families with autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) are at 50% risk of inheriting a causative mutation for AD (i.e., in the PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP genes) from their affected biological parent. Virtually all mutation carriers (MCs) will develop symptomatic AD, generally at the same age as their affected parent (the mean age of symptom onset in ADAD families is ~46 years), whereas their sibling non-carriers have no more risk for AD than the general population. The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) has demonstrated that abnormal levels of Aβ42 (the most pathogenic isoform of Aβ) measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) begin in asymptomatic MCs about 20–25 years prior to estimated age at onset (AAO) for symptomatic AD (Bateman et al., 2012). Cerebral deposits of fibrillar Aβ are detected with molecular imaging about 15 years prior to estimated AAO, as are abnormalities in CSF levels of tau protein (and of its phosphorylated species); volumetric brain loss also is detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) about 15 years prior to estimated AAO. Brain hypometabolism and deficits in episodic memory performance occur about 10 years before estimated AAO, and global cognitive impairment begins about 5 years before estimated AAO (Bateman et al., 2012). These findings are consistent with a continuous pathologic cascade in preclinical AD that ultimately manifests as symptomatic AD and suggest that abnormalities in Aβ metabolism begin more than two decades before symptomatic onset of AD. This provides a potential “window” for prevention therapies in asymptomatic individuals who are destined to develop symptomatic AD and further offers the opportunity to directly test the amyloid hypothesis with clinical trials of anti-Aβ monotherapies in asymptomatic MCs with preclinical AD. The extent to which these observations in DIAN extrapolate to the far more common “sporadic” form of late onset AD is unknown. Because abnormal biomarkers were present in DIAN only in MCs destined to develop symptomatic AD, however, it is likely that the same biomarker abnormalities in cognitively normal older adults also will predict symptomatic AD if the individuals continue to live.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

In 1984 uniform clinical diagnostic criteria were introduced by a Work Group convened by the National Institute on Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) (McKhann et al., 1984). These criteria provided the basis for the accurate recognition of the clinical disorder. The application of these clinical criteria firmly established AD as the dominant cause of dementia. The NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for the diagnosis of probable AD have been the underpinnings of AD clinical trials and research for over 25 years. To incorporate new knowledge resulting from this research, NIA-AA work groups recently updated these criteria. The new criteria recognize AD as a neuropathological entity that progresses from an asymptomatic stage (preclinical AD; Sperling et al., 2011) to a prodromal symptomatic stage (mild cognitive impairment; Albert et al., 2011) to the fully expressed AD dementia syndrome (McKhann et al., 2011). By definition, preclinical AD presently is detected solely by biomarkers, antecedent to symptomatic stages of AD. Only the clinical diagnosis of symptomatic AD, encompassing MCI and AD dementia, is addressed here.

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

The term mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was introduced to characterize the boundary of aging and dementia (Flicker et al., 1991). The earliest symptoms of AD are insidious and almost all patients with AD progress through a stage of subtle cognitive impairment that may not interfere importantly with daily functioning. Clinical criteria for MCI were intended to characterize this prodromal stage, prior to the diagnosis of overt dementia (Petersen et al., 1995). Because MCI was not defined as a clinicopathologic entity, however, it can represent the earliest symptomatic stage of many underlying pathologies (not all of which necessarily progress to dementia) and thus MCI is heterogeneous in nature with highly variable outcomes.

The revised criteria for MCI move toward providing an etiologic diagnosis for this condition when it is considered to be a symptomatic predementia phase of AD (Albert et al., 2011). These criteria nominally appear consistent with consensus criteria for MCI published in 2004 (Winblad et al., 2004) and require: (1) a change in cognition, self-reported or noted by an observer; (2) objective impairment in one or more cognitive domains; (3) independence in functional activities; and (4) absence of dementia (because functional independence is preserved). Unfortunately, the revised criteria for MCI broaden the definition of “independence in functional activities” to include “mild problems performing complex tasks . . . such as paying bills, preparing a meal, or shopping” and allow reliance on aids and assistance to accomplish these tasks to qualify as “independent.” Because the differentiation of MCI from dementia rests solely on the criterion of functional independence (McKhann et al., 2011), this blurring of what represents “independence” leaves the diagnostic distinction entirely to the individual judgment of the clinician, resulting in nonstandard and arbitrary classifications (Morris, 2012). The “problematic” threshold for distinguishing the “essentially preserved” functional activities in MCI from the subtle functional deficits that accompany the milder stages of AD dementia (Petersen, 2004), combined with the heterogeneity of MCI, have left the field struggling to characterize this condition. In response, some investigators have recommended that the term “MCI” be replaced by etiological diagnoses, particularly when AD is believed to be the underlying causative disorder as determined by an appropriate clinical phenotype and/or by biomarker evidence (Dubois et al., 2010; Morris, 2012) (Table 59.1).

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

Revised criteria for probable AD dementia include the presence of dementia and no evidence for other dementing conditions (neurologic disorders or medical comorbidities) or medications that can substantively impair cognition (Table 59.1). When there is an atypical course or an etiologically mixed presentation, possible AD dementia is diagnosed. These criteria recognize advances in AD biomarkers and, when deemed appropriate by the clinician, encourage their use to enhance confidence that the etiology of the dementia syndrome is AD. Biomarkers reflect either the molecular pathology of AD or the presumed downstream effects of the underlying pathology (Table 59.2). The primary use of AD biomarkers currently remains in investigational studies but increasingly will become optional diagnostic tools. Indeed, the Food and Drug Administration in April 2012 approved the use of the 18F amyloid imaging tracer, florbetapir, for the indication of “brain imaging of amyloid plaques in patients . . . being evaluated for AD and other causes of cognitive decline” (“FDA Approves Amyvid®,” 2012). Nonetheless, much work is needed before the clinical utility of AD biomarkers for diagnostic considerations can be fully realized. A biomarker should detect a fundamental feature of AD neuropathology and should be validated using histopathologically confirmed AD cases. A biomarker should be precise in that it should detect AD early in its course and distinguish it from other dementias. Both the sensitivity and specificity of an AD biomarker should be at least 80%, with a positive predictive value approaching 90%. Biomarkers represent continuous biological processes, yet the cutpoints to define a “positive” or “negative” test impose an artificial dichotomous outcome on this continuum and will occasionally produce ambiguous or indeterminate results. There is a great need to standardize both the CSF and imaging biomarkers across laboratories. Practicing physicians have varying degrees of access to AD biomarkers, and reimbursement procedures have yet to be established. An ideal biomarker should be reliable, non-invasive, simple to perform, and inexpensive. The ultimate “test” will be to determine the utility of AD biomarkers in the clinic (Schoonenboom et al., 2012). Although the revised criteria for AD dementia do not recommend the use of biomarkers for routine diagnostic purposes, other proposed criteria now require biomarker evidence for the diagnosis of AD (Dubois et al., 2010).

TABLE 59.1. Current versions of lexicons and diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease

|

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR1; 2000) Criteria for AD: the development of memory impairment and deficits in executive function, language, praxis, and/or perception that represent a decline from previous functioning, impair social or occupational activities, have a gradual onset and progression, and are not attributable to another disease |

|

2. International Working Group for New Research Criteria for the Diagnosis of AD (Dubois et al., 2010) Alzheimer’s disease: use of this term is restricted to the clinical disorder, encompassing the full symptomatic spectrum from predementia to dementia. The diagnosis is established by the presence of episodic memory loss and imaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker evidence of AD. The term “AD” can be subdivided into “prodromal AD” (predementia stage of AD) when instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are preserved and “AD dementia” when the cognitive loss interferes with IADLs AD pathology: the neurobiologic changes responsible for AD, regardless of whether the clinical disorder is present Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI): cognitive impairment that is too mild to interfere with IADLs but for which no attributable disease can be discerned |

|

3. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for AD (Albert et al., 2011; McKhann et al., 2011; Sperling et al., 2011) Dementia: encompass the spectrum of dementia, from the mildest to most severe stages, and defined as cognitive deficits that represent a decline from previous levels of function and interfere with IADLs AD dementia: meets criteria for dementia, and cognitive decline is marked by insidious onset with progressive worsening and other illnesses that can explain or contribute to the cognitive loss are absent. Biomarker evidence for AD may enhance confidence in the clinical diagnosis, but such evidence is not presently ready to be incorporated into the routine diagnostic process MCI due to AD: concern about cognitive change (either self-reported or from an informant or observer), impaired performance in one or more cognitive domains, and independence in IADLs (distinguishing this condition from dementia). However, “independence” is expansively operationalized to include problems in performing IADLs and to include dependence on aids or assistance to function in daily life. AD biomarkers may be used to increase certainty that AD pathology is the cause of MCI, although currently there remain limitations in how biomarker evidence is interpreted. Preclinical AD: AD is defined as the underlying neuropathologic disorder and represents a continuum of pathophysiologic changes that eventually result in cognitive decline. Biomarkers of AD pathology provide hypothetical staging categories for preclinical AD (i.e., when cognitive symptoms and decline are undetectable by current clinical methods but AD lesions are present in the brain) |

|

4. Washington University (Morris, 2012) Alzheimer’s disease: the neurodegenerative brain disorder, regardless of clinical status, that results in a continuous process of synaptic and neuronal deterioration • AD is characterized by two major stages: • Symptomatic AD is defined by intra-individual cognitive decline that interferes (from subtle to severe) with daily function. It can be subclassified on severity of symptoms: |

|

Biomarkers for the molecular pathology of AD |

|

Cerebrospinal fluid Reduced levels of amyloid β-42 (Aβ42) Elevated levels of total tau or phosphorylated tau (p-tau) |

|

Positron emission tomography (PET) Retention in cerebral cortex of amyloid tracers such as [11C] Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) or [18F] Florbetapir (Amyvid®) |

|

Biomarkers for the consequences of AD pathology |

|

PET Hypometabolism in temporoparietal cortex as demonstrated by decreased [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake |

|

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Volume loss in: Hippocampus Medial, basal, lateral temporal lobe Medial parietal lobe Whole brain |

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

Because biomarkers have not yet been established for clinical practice, clinical methods currently provide the key information needed to diagnose AD dementia and create a differential diagnosis: history taking, mental status testing, and neurological examination. The diagnosis of AD dementia at present rests on the documentation of (1) intraindividual cognitive decline that (2) interferes with daily function.

HISTORY TAKING

Serial cognitive testing provides objective evidence of progressive cognitive decline but such data rarely are available in the acute patient care setting. Fortunately, the observations of a knowledgeable informant also are sensitive and reliable for detecting meaningful intraindividual cognitive decline that characterizes dementia (Carr et al., 2000). Whenever possible, therefore, a person who knows the patient well should be interviewed to assess whether the individual’s current levels of cognitive function represent a decline from previously attained levels. In this way, the patient serves as his or her own control and mitigates the fact that specific cognitive strengths and weaknesses and activities of daily life vary widely among individuals. Factors that can influence cognitive test performance, such as literacy and educational attainment, native language, and cultural background, also are minimized. Even in the early stages of AD dementia, most patients lack insight into their cognitive problems. Patient self-report thus is less reliable that the report of an informant (Carr et al., 2000).

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is an informant-based clinical assessment and dementia staging instrument that is widely used in research settings to determine the presence of absence of dementia and, when present, its severity (Morris, 1993). Semistructured interviews are conducted by an experienced clinician independently with the informant and the patient to assess the patient’s abilities in each of six domains: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, function in community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. Incorporated into the interviews are portions of the Dementia Scale (informant) and Information-Memory-Orientation test (patient) (Blessed et al., 1968), and also included are an aphasia battery, medical and psychiatric histories, and medication inventory. Using all information, the clinician rates each of the six CDR domains along five levels of impairment from none to maximal (rated as 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3). Combining the domain scores in accordance with a scoring algorithm produces a global CDR score, where 0 indicates cognitive normality and 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 indicate very mild, mild, moderate, and severe dementia.

The CDR is the primary global staging instrument for the Uniform Data Set (UDS; Morris et al., 2006; Weintraub et al., 2009), which, since 2005 has been the standard clinical and cognitive instrument for the evaluation of all cognitively normal control participants and individuals with MCI and AD dementia at the federally funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs). Also included in the UDS are additional informant-based scales that capture other aspects of dementia, including neuropsychiatric features (Neuropsychiatric Inventory; Cummings et al., 1994), and functional abilities (Functional Assessment Questionnaire; Pfeffer et al., 1982). Mood and depression are assessed in the patient with the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al., 1983). Few practitioners, however, have the training and expertise, much less the time, to administer the UDS or derive the CDR. A derivative of the informant portion of the semistructured interview used to score the CDR is the Ascertain Dementia 8 (AD8; Galvin et al., 2005), a brief eight-item questionnaire that can be used in practice settings as a dementia screening tool.

The AD8 can be completed in two to three minutes and can be administered in person or by telephone; it also can be self-administered by the informant. The eight questions (Table 59.3) ask whether there has been a change due to cognitive decline in the ability of the patient to perform daily tasks. Scores of 2 or more on the AD8 provide good discrimination between cognitive normality and even early-stage AD dementia with a positive predictive value of 87% (Galvin et al., 2005). Poor performance on the AD8 corresponds to biomarker evidence of AD dementia (Galvin et al., 2010). However, the AD8 is a screening, not a diagnostic, instrument and should be used to identify persons who would benefit from an evaluation for possible dementia.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL TESTING

MENTAL STATUS TESTS

Standard cognitive testing can be very useful at the bedside. The ideal information for detecting dementia comes not from a comparison of an individual’s cognitive performance with others (i.e., comparison of individual performance with normative values derived from age- and education-matched controls), but from whether an individual has declined from his/her past abilities. Such information is best captured at an initial evaluation by a careful history. Bedside cognitive testing is often accomplished using mental status tests, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975). The MMSE is widely used and has modest sensitivity but fair specificity for detecting dementia (Galvin et al., 2005). The accuracy of the MMSE depends on the age, cultural background, and educational level of the individual. A standard cutpoint score of 23 or less as indicative of dementia has poor accuracy in individuals with education levels at the low and high end of the spectrum (Galvin et al., 2005). In addition, individuals who receive a clinical diagnosis of MCI often score in the normal range for elderly adults (Ismail et al., 2010). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., 2005) is another popular bedside mental status examination that was designed to be more sensitive to frontal and subcortical pathology and to detect cognitive changes in individuals who score in the normal range on the MMSE. Like the MMSE, the MoCA has been validated in several languages and cultures. Some reports show the MoCA to be superior to the MMSE in sensitivity and specificity for detecting MCI and AD (Freitas et al., 2011).

TABLE 59.3. The AD8: dementia screening interview to differentiate aging and dementia

| Is there repetition of questions, stories, or statements? |

| Are appointments forgotten? |

| Is there poor judgment (e.g., buys inappropriate items, poor driving decisions)? |

| Is there difficulty with financial affairs (e.g., paying bills, balancing checkbook)? |

| Is there difficulty in learning or operating appliances (e.g., television remote control, microwave oven)? |

| Is the correct month or year forgotten? |

| Is there decreased interest in hobbies and usual activities? |

| Is there overall a problem with thinking and/or memory? |

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

Although mental status tests can be useful to screen for the presence of global cognitive difficulties, they are not designed to detect the subtle cognitive changes seen in early symptomatic AD and can be strongly affected by the demographic characteristics of the patient. Mental status tests also cannot provide a comprehensive assessment of specific domains of cognitive functioning, which can be critical for differential diagnosis, tracking change over time, and for treatment planning. A full neuropsychological evaluation is useful when there is a question of more subtle cognitive impairment, or when a more thorough assessment of cognitive strengths and weaknesses is necessary. Neuropsychological evaluations are also indicated when attempting to establish the cognitive fitness or competency of an individual with dementia to perform activities of daily living, including working and driving, and their capacity to make medical, legal, and financial decisions (Moberg and Kniele, 2006). In moderate to severe AD (CDR 2–3), neuropsychological assessment becomes less useful, because patients with advanced AD have pronounced global cognitive deficits that preclude testing. A typical neuropsychology referral involves history taking with the patient and often an informant, and several hours of testing using standardized measures of cognitive functioning. The neuropsychologist then compares the cognitive profile of the individual to normative data (see section on normative data in neuropsychological assessment for more information) and generates a report describing the cognitive profile and the most likely contributing factors, and may include recommendations for treatment. Tests administered usually include an estimate of premorbid functioning and assessments of fluid and crystallized intelligence, attention, working memory, processing speed, visuospatial skills, language, executive functioning, and several aspects of memory. Mood and personality assessments may also be completed. Neuropsychologists are typically Ph.D. level clinical psychologists who, in addition to training in psychopathology and psychotherapy, have completed specialized internship and fellowship training in neuropsychological assessment. As such, they are well suited for assessment of mood and personality and can play a valuable role in differential diagnosis.

NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION

The neurological examination is a standard part of the assessment of a patient with dementia to detect neurological deficits and signs that may suggest possible causes of dementia. In typical AD dementia, the neurological examination is nonfocal and generally unremarkable, particularly in the mild-moderate stages. In more advanced AD dementia, the apparent inability to cooperate may result in gegenhalten (oppositional resistance) when limb muscles are passively stretched. Cortical release signs (suck and grasp reflexes) may be elicited in late-stage AD dementia, and not infrequently there are mild extrapyramidal signs (usually bradykinesia and gait and tone abnormalities) and occasionally myoclonus. The risk of seizures is increased in advanced AD dementia (Romanelli et al., 1990) but seizures are uncommon in the mild-moderate stages (Irizarry et al., 2012).

Aphasia (language dysfunction), apraxia (disordered purposeful movement, distinct from paresis), and agnosia (disordered perception) may develop in later stages of AD dementia. For individuals with milder stages of dementia, deficits in these areas usually are limited to word-finding difficulty for names of people and objects (dysnomia) and perhaps constructional apraxia (i.e., visuospatial impairment as manifested by poor clock drawing performance). Occasionally, AD dementia presents as an asymmetric (“focal”) cortical syndrome. Unexplained language dysfunction with relative sparing of memory may indicate the presence of a variant of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, such as nonfluent progressive aphasia or semantic dementia, but atypical AD also can cause progressive aphasia. AD also can present as posterior cortical dysfunction (Renner et al., 2004). The dysfunction can include partial or full examples of the disconnection syndrome, alexia without agraphia (generally involving pathology in the left occipital lobe and splenium of the corpus callosum) and Gerstmann syndrome (dyscalculia, agraphia, right-left disorientation, and finger agnosia), implicating pathology in the left parietal lobe. In one series of 100 “focal” cortical syndrome cases that were examined postmortem, 34 of 100 were attributed to histopathological AD and close to one-half (12 of 26) of the cases with progressive aphasia had neuropathologic AD (Alladi et al., 2007). Visual agnosias include Balint syndrome, where there is failure to properly synthesize all components in the visual field (simultanagnosia) owing to bilateral occipitoparietal pathology that occasionally can be AD (Graff-Radford et al., 1993).

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Depression, B12 deficiency, polypharmacy, and hypothyroidism are not infrequent disorders in older adults and have been associated with cognitive impairment. Screening for these treatable disorders is recommended in the evaluation of possible contributors to dementia (Knopman et al., 2001). Treatment of these disorders is unlikely to completely reverse cognitive deficits. Nevertheless, the high frequency of these co-morbidities and the potential for at least partial amelioration of cognitive symptoms justifies screening.

RADIOLOGICAL EVALUATION

STRUCTURAL IMAGING

Structural neuroimaging, either MRI or non-contrast computed tomography, is recommended to evaluate potential causes of dementia (Knopman et al., 2001). Up to 5% of patients with dementia have imaging evidence for brain neoplasms, subdural hematomas, communicating hydrocephalus, or other structural lesions that may contribute to the cognitive symptoms. Although not specific for AD, neuroanatomic changes consistently have been linked with AD brain pathology and MRI volumetrics are increasingly being used as a “downstream” biomarker for AD dementia that indirectly detects cell loss and AD neuropathological burden (Du et al., 2003; Jack et al., 2002). Cerebral atrophy also is associated with normal aging (Fotenos et al., 2005). Programs have been developed to indicate whether the degree of quantitative volumetric loss (either regional, such as for the hippocampus, or whole brain) falls in the range of “normal” or “pathologic” atrophy.

PHENOMENOLOGY OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

Course

Alzheimer’s disease is a uniformly fatal disorder. The duration of AD dementia, from initial appearance of symptoms until death, averages 7 to 10 years, although shorter and longer periods of survival are not uncommon. Staging of dementia generally describes three levels of severity: very mild/mild (corresponding to CDR 0.5 and CDR 1), moderate (CDR 2), and advanced (CDR 3). Although an inevitably progressive disorder, the rate of progression of AD dementia is stage-dependent such that the less the dementia severity, the slower the rate of progression. For example, the median time to progression to a higher CDR score was 3.07 years for CDR 0.5 individuals with AD dementia versus 2.41 years for CDR 1 individuals (Williams et al., 2012). Older age and the presence of the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) are associated with more rapid progression (Cosentino et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2012).

FEATURES OF VERY MILD/MILD ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

The evaluation seldom is sought by the patient, who typically is unaware that there is a “problem,” but most often by family or friends. The clinical hallmark of AD dementia is impairment in the learning and retention of new knowledge, such that details of events and conversations are not recalled and questions and statements often are repeated. Performance for autobiographical memory, where the individual’s ability to correctly recall events (independently related by the family) in which s/he had recently participated is assessed, is at least as informative for memory function as brief memory tests (Dreyfus et al., 2010). Patients may have difficulty in remembering appointments or to take their medications and often demonstrate misplacement of items without independent retrieval. Temporal and geographical disorientation may result in forgetting the date or day of the week and difficulty in navigating unfamiliar areas. Executive dysfunction is manifested by less facility in organizing information and in impaired decision-making. There is less ability to perform cognitively demanding behaviors, such as operating a motor vehicle or managing the household finances (Table 59.4). Although language skills generally are preserved, difficulties with word retrieval are common and may result in slow, hesitant speech. Personality generally is maintained, although family and friends may note that the affected individual is “quieter” or withdrawn, especially in social settings. Many activities in the community (shopping; attending religious services) and at home (cooking; laundry) still may be performed, if less well than previously, without assistance from others and self-care tasks (dressing, grooming, bathing, toileting) generally are completed independently. Hence, to the casual observer the affected person looks and acts normally, and it is only those who know the person well who are aware of the decline from previously attained levels of cognition and function.

TABLE 59.4. Alzheimer’s disease dementia clinical phenotype: mild stage

| Gradual onset and progression |

|

Informant report

Frequent repetition, misplaced items, difficulty recalling names Functional impairment

Affected individual

|

|

Keys

Decline from prior levels Consistency of problems Interference with daily function |

|

Probe for intraindividual cognitive decline

Ask if a “problem” represents a change from prior abilities |

| Obtain concrete examples of how cognitive problems interfere with everyday function |

|

Use judgment

Discordance of informant report vs. individual performance Alzheimer dementia phenotype can be present in high-functioning persons who still perform well on tests Individual’s self-report of whether or not there are cognitive problems often is unreliable |

FEATURES OF MODERATE ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

Progressive decline in cognitive and functional abilities now necessitates supervision for almost all aspects of the individual’s daily life, and the dementia is obvious even to people who do not know the patient well. New information quickly is forgotten, and recall of even highly learned information may be impaired. Attention also is impaired and the patient is more distractible, with the consequence that attempted tasks are not completed. Disorientation for even familiar settings may result in the individual failing to recognize a home they have visited many times. Elopement is a serious risk as the patient cannot find the way home nor communicate appropriately to others where they live or with whom. Judgment and problem solving abilities are notably impaired, such that it is unsafe for the individual to be home alone because of safety and security concerns (e.g., leaving the doors unlocked; inviting strangers into the house; failing to turn off the stove burners; acquiesce to solicitations for money). The affected individual also must be accompanied in all activities outside of the home. Although the individual may engage in some basic tasks, including cooking, cleaning, and self-care, these generally require supervision. Although patients may continue to dress themselves, supervision may be needed to ensure that the patient does not repeatedly wear the same soiled clothes or put them on improperly; prompting often is needed to have them bathe. Medications must be administered to the patient. The increased dependence of the patient often results in considerable burden for the primary caregiver, who most often is the spouse or adult child of the patient, and negatively affects the caregiver’s health. Additional care often is sought from unpaid (family and friends) and paid caregivers. Institutionalization also may be considered, particularly when there is frequent incontinence, wandering, or behavioral abnormalities.

ADVANCED ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DEMENTIA

Patients in the advanced stages of AD dementia lack comprehension, may no longer remember loved ones, and fail to recognize their home or other familiar surroundings. They lose the ability to perform even simple activities of daily living. Night and day are confused. Eventually patients become near-mute and nonambulatory and require total care for dressing, hygiene, eating, and toilet functions as sphincter control is lost. The patient ultimately succumbs to medical complications such as inanition, aspiration, pneumonia, and sepsis arising from urinary tract infections or decubitus ulcers.

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC FEATURES

Neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms are common in AD dementia and contribute to the clinical profile of the disease. Neuropsychiatric problems do not occur in all persons with AD dementia, but generally emerge during the moderate stage of dementia. Neuropsychiatric symptoms can be subclassified as mood disturbances, psychosis (delusions and hallucinations), and personality changes and are observed in a majority of patients with dementia (Sink et al., 2005). Neuroimaging and pathological studies have demonstrated that neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms reflect associations with regional pathology as indicated by discrete areas of atrophy, hypometabolism or decreased blood flow (Bruen et al., 2008). For instance, patients with apathy are more likely to have disproportionate dysfunction in the medial frontal and anterior cingulate regions, whereas agitation is higher in those with increased NFT burden in the left orbitofrontal cortex.

The relationship of AD and depression is complicated, but 30% or more of individuals with AD dementia will have at least some depressive features, although the percent meeting criteria for major affective disorder is much lower (Olin et al., 2002). Depressive symptoms in individuals with AD may be a manifestation of pathology in the locus ceruleus and the substantia nigra and thus may be an early symptom of AD pathology (Bruen et al., 2008). Importantly, effectively treating depression can have an impact on the severity of cognitive-related disability, and a low threshold for treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with cognitive impairment is important as some associated cognitive impairments may be improved (McNeil, 1999).

Agitation and aggression are particularly difficult to manage. Agitation represents disruptive psychomotor activity. Hallucinations and delusions occur in about 30% of cases at some point during the course of the illness (Lyketsos et al., 2002). Visual hallucinations are a key feature of dementia with Lewy bodies but are less common in AD and, when present, generally occur in the later stages. Delusions of spousal infidelity and theft are common. Misidentification syndromes such as the Capgras syndrome or reduplicative paramnesia can also occur. Capgras syndrome is the belief that a family member or friend has been replaced by an identical appearing impostor. Reduplicative paramnesia is the delusion that a place (such as one’s house) has been duplicated in and exists in two or more places. For instance, the patient may believe their house is somewhere else and that the house they are in is identical to their own. Treating these distressing neuropsychiatric symptoms should first seek to identify the possible physical, social, and environmental precipitants and to remove or reverse them. When non-pharmacologic interventions fail, atypical antipsychotics may provide some relief from agitation or psychosis but randomized clinical trials generally fail to demonstrate benefit (Sink et al., 2005). Metaanalyses indicate that the use of antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia is associated with increased mortality, primarily related to cardiovascular events.

BIOMARKERS FOR ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

An autopsy study of 919 individuals with a clinical diagnosis of AD dementia at federally-funded ADCs found that the clinical diagnosis was relatively inaccurate, with mismatches between the clinical and neuropathologic diagnoses in 16.7% of cases (Beach et al., 2012). Although it is possible that the ADCs were referred more complicated cases than are encountered in routine practice, the expertise of these tertiary care centers might be expected to compensate and yield more accurate diagnoses. Hence, diagnostic misclassification is not inconsiderable for cases of presumed AD dementia. The advent of biomarkers of the molecular pathology of AD is anticipated to improve clinical diagnostic accuracy. Biomarkers also may provide more precise and sensitive measures of disease progression and may allow shorter trials with smaller sample sizes by using biomarkers as surrogate end points. For example, in early symptomatic AD, individuals who were most likely to cognitively decline rapidly were identified by CSF markers for AD (Snider et al., 2009), potentially helping to reduce the number of participants needed to demonstrate a drug effect in trials of MCI and early-stage AD individuals.

Despite promising results, biomarkers must be shown to be at least as accurate as clinical diagnosis alone before their role in the routine assessment in patients with cognitive impairment can be determined. It is likely that a panel of biomarkers rather than a single test will have the most utility for the diagnosis of AD and, in cognitively normal persons, for predicting who will progress to symptomatic AD (de de Leon et al., 2001). A major remaining problem for the field is the lack of standardization of the analytic techniques to determine CSF biomarkers. Even the time of collection of CSF is important as CSF Aβ42 levels have diurnal fluctuations (Batemen et al., 2007). Different assay platforms also introduce variability. Harmonization of laboratory measurements are needed to minimize current intercenter variations in CSF assays (Mattsson et al., 2011).

Although there remains some uncertainty as to precisely how biomarkers will ultimately be incorporated into the standard evaluation of cognitive impairment, a variety of biomarker measures are currently available for the practicing physician and may provide clinically relevant information in specific circumstances. Measures of amyloid and tau in CSF are commercially available. Although the PET radioligand 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB; Klunk et al., 2004) has dominated amyloid imaging research because it enters the human brain rapidly and has very high selectivity and nanomolar affinity for Aβ plaques, it has a half-life of only 20 minutes. Its use is thus limited to medical centers with on-site cyclotrons and 11C radiochemistry expertise. Tracers labeled with 18F have a longer half-life (close to two hours) and allow for wider distribution from commercial producers.

Amyloid imaging with 18F florbetapir now is commercially available for detecting the presence of cerebral amyloid deposits in individuals with cognitive decline and additional 18F amyloid tracers are in development. Structural neuroimaging techniques are becoming readily available for volumetric quantification. The use of biomarkers to aid the clinical evaluation of individuals with cognitive impairment is likely to accelerate in coming years. Early recognition of disease will be increasingly important if disease modifying therapies are developed, in particular because those therapies are likely to have greatest efficacy early in the course of disease before major neurodegeneration has occurred.

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a number of modifiable risk factors. Cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia are associated with a higher risk of developing AD, whereas lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet (low fat consumption, moderate alcohol consumption, Mediterranean diet), and cognitive engagement are associated with a lower risk of developing AD. These observations suggest that interventions designed to modify these factors may influence AD risk. The observational nature of the data and methodological limitations of the studies, however, limit the scientific quality of the data and make them insufficient for drawing firm conclusions on the association of any modifiable risk factor with cognitive decline or AD. Further studies are necessary, including long-term population-based studies and randomized controlled trials to further investigate these strategies. Intriguing but nonsignificant data from a population-cohort study suggests that age-adjusted dementia incidence may be declining (Schrijvers et al., 2012). This observation would be consistent with a concept that risk of dementia may be modifiable by trends in social (increased years of education) and medical (better treatment of cardiovascular disease) factors; it also is inconsistent with dementia as an inevitable consequence of aging (Larson and Langa, 2012).

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

The limbic structures, including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, are among the brain regions involved in the earliest stage of symptomatic AD, with increasing involvement of frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices as the disease progresses (e.g., Bondi et al., 2008; Braak and Braak, 1991). In line with this, numerous studies have shown that episodic memory tasks typically are the first to evidence change in symptomatic AD and the structures underlying episodic memory function (medial temporal lobe, precuneus, and other limbic areas) are the first to show changes in volume, connectivity, and task-related brain activity (Bondi et al., 2008; Buckner et al., 2009). These changes also are excellent predictors of disease state (Putcha et al., 2011; Yassa et al., 2011). The AD dementia syndrome is thus characterized by prominent episodic memory deficits with rapid forgetting of material, executive dysfunction, and additional deficits in certain aspects of language, visuospatial abilities, and attention.

Subtle declines in episodic memory in older adults may precede the recognition of symptomatic AD (see Bondi et al., 2008 for review). The traditional view that the first cognitive change is represented by episodic memory deficits may not always be the case. As Storandt (2008) notes, a circularity bias exits when group designations such as MCI are based on neuropsychological status. For example, if a diagnosis of MCI is contingent on episodic memory deficits, it is not surprising that affected individuals most often exhibit significant differences in episodic memory. Longitudinal cognitive and clinical assessments over several years in individuals who subsequently had AD confirmed that deficits occur in non-episodic memory domains in over one-third of cases (Storandt, 2008; Storandt et al., 2006). Personality changes, difficulties with executive or visuospatial functions, slowing of psychomotor speed, or combinations of these appeared to mark initial cognitive decline in some persons (Johnson et al., 2009; Storandt, 2008). Information about intraindividual changes that is gathered from collateral sources also detected subtle cognitive decline that was so minimal it did not meet the cutoffs used to classify MCI. Similarly, others have reported that persons without dementia but with notable personality changes were much more likely to develop dementia two years later (see Storandt, 2008, for review).

Difficulties with attention and executive functioning commonly occur in patients at early stages of AD, and continue to worsen with the progression of the disease. It may be the case that early episodic memory deficits are a result of multiple factors, including difficulty with attention and executive functioning mechanisms. Attention and executive functioning represent somewhat overlapping constructs with many aspects, but the processes of inhibitory control and maintenance of task sets appear to play a critical role in early AD (Buckner, 2004; Storandt, 2008). Neuropsychological tasks that emphasize these processes are very sensitive indicators of the early stage of symptomatic AD. For example, the Stroop test (Stroop, 1935) and the Trail Making test (Reitan, 1992) are good examples of measures that assess these processes. The incongruent condition of the Stroop test requires the patient to inhibit a more salient overlearned response (reading a word) in favor of a less salient response (naming the contrasting ink color). Patients with symptomatic AD, even at early stages, will perform much more slowly and make more errors on this task compared with the baseline conditions where they are asked to simply read words or name color blotches (Amieva et al., 2004). Similarly, individuals with symptomatic AD will have considerable difficulty on the Trail Making B test, which requires them to switch between one overlearned task to another overlearned task to connect a series of numbers and letters (Albert, 2008).

NORMATIVE DATA IN NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Clinical assessment of an individual can be understood as having two distinct forms. An idiographic approach considers the individual as a unique agent with characteristics that set him or her apart from other individuals and refers to theories that are applicable to that specific case. In contrast, the nomothetic approach describes general laws of functioning that apply to all individuals and groups of individuals (Persons and Tompkins, 1997). Neuropsychological assessment emphasizes the nomothetic approach, in that a patient’s score on a cognitive test is compared to the average performance of a larger group of demographically similar individuals who are typically free from disease. This larger group is referred to as a normative data set and may include individuals with a wide range of demographics (e.g., ages, educational achievement) and linguistic and ethnic backgrounds. In addition to healthy normative data sets, a patient’s score can be compared to disease- (e.g., MCI or dementia) or cohort- (e.g., inpatients, on/off medications, age-groups) specific normative data sets. Normative data often are provided by the authors or publishers of a particular test or by other investigators attempting to validate an instrument in a particular clinical population. Attending carefully to the selection of normative data sets for clinical application is critical for interpretation of raw test scores. Normative data can be quite heterogeneous in terms of the size and demographics of the sample, and the time at which the data were collected may introduce cohort effects. Normative data sets are not consistent in accounting for potential moderator variables such as education, gender, or cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Manly, 2008). Also, generalizability may be compromised by geographic limitations, because the samples may be representative of a certain region or collection of disparate regions in the United States or elsewhere (Kalechstein et al., 1998). Differences between these normative samples can significantly alter interpretation of test results. Kalechstein, van Gorp, and Rapport (1998) applied different sets of normative data to scores on commonly used cognitive tests for a group of individuals of various ages and education levels. Interpretation of performance was drastically affected depending on which set of normative data were used for comparison. In the most extreme cases, a score from a single test could span as many as four clinical classifications (e.g., Average, Low Average, Borderline, and Impaired). In other words, the percentile rank for a score on a single test could range from greater than the 25th percentile (Average) to less than the 2nd percentile (Impaired), depending on which normative data set was used for comparison.

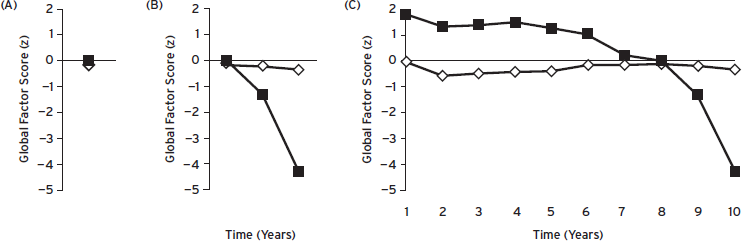

Several studies have noted that many individuals continue to perform well on cognitive tests despite having substantial neuropathological abnormalities that ultimately lead to symptomatic AD (Knopman et al., 2003; Price et al., 2009; Schmitt et al., 2000). These individuals tend to be more educated, have larger brain volumes, and may be more socially engaged (James et al., 2011; Roe et al., 2011; Scarmeas and Stern, 2003). This phenomenon has been described as a reserve capacity that may prolong the prodromal period of AD (Roe et al., 2011). However, others have noted that an overreliance on insensitive cognitive tests and the relatively few studies that track intraindividual change may fail to detect subtle cognitive decline in these individuals. Although serial neuropsychological evaluation is ideal for assessment of intraindividual change, this may be impractical for a number of reasons. Thus, most referrals for neuropsychological assessment provide a cross-sectional view of cognitive functioning. Without a careful history taking, which should include the patient and a reliable informant, it is possible that an apparently normal-looking cognitive profile may actually represent a significant decline from a former level of cognitive functioning (Fig. 59.1). This is often the case for high-functioning individuals.

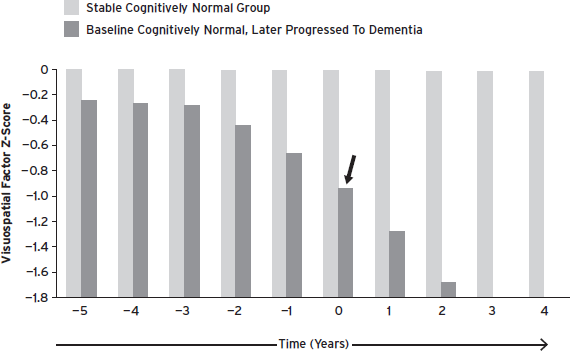

Storandt and Morris (2010) describe an ascertainment bias, which highlights methodological issues related to determining the clinical diagnosis of dementia. They point out that many studies of so-called “cognitive reserve” have used insensitive mental status examinations as the only outcome measures. They also note that individuals who already have early cognitive impairment are included in normative samples, thereby lowering the group mean and reducing the sensitivity to detect impairment (Fig. 59.2). In a carefully assessed sample that was followed through autopsy confirmation of AD, application of commonly used standard deviation cutoffs of −1.0 or −1.5 on episodic memory tests detected only 23% and 44%, respectively, of patients who later developed AD. When this same sample was compared with a robust control group composed of individuals who never progressed to CDR greater than 0, sensitivity and specificity increased greatly but still was inaccurate in over 30% of cases (Storandt and Morris, 2010). These findings underscore the need for development of robust normative data, and also emphasize that an approach that uses standard deviation cutoff scores for classification may not be ideal, even with very robust normative data.

One potential solution is the development of a single comprehensive set of normative data that would include a large, demographically and geographically diverse sample with complete biomarker and neuroimaging data. Cerebrospinal fluid analytes and neuroimaging markers (including structural and functional MRI, amyloid imaging, and white matter imaging) could be used to identify individuals most likely to develop AD and classify them appropriately in the normative data set. An individual’s cognitive profile could then be compared with the normative group that is free of detectable AD neuropathology and could also be compared with a group with AD neuropathology but who show no clinical symptoms. However, this would be a costly and likely impractical endeavor making a set of “local norms” an appealing option (Kalechstein et al., 1998). Local norms would have the advantage of being ideally similar to the group to which each individual would be compared.

Figure 59.1 Global factor Z-score cognitive trajectories for two individuals seen over 10 annual follow-up visits. (A) At follow-up visit 8, both individuals score very close to the mean of the reference sample, indicating “normal” cognitive performance. (B) In subsequent assessments, one individual (filled black squares) declined at visit 9 to approximately 1.5 standard deviations below the mean performance of the reference sample and at visit 10 to over four standard deviations below the mean of the reference sample. (C), Cognitive performance at assessments prior to visit 8 for the same individual (filled black squares) reveal that decline had begun well before visit 8. Based on visit-specific neuropsychological performance alone, this individual might be considered as “cognitively normal” (visit 8) or “mild cognitive impairment” (visit 9), but neither of these considerations can be supported once intraindividual decline is taken into account. (Courtesy of Storandt, M.)

Figure 59.2 Longitudinal change in visuospatial domain factor scores in older adults who were cognitively normal at entry. The stable cognitively normal group never progressed to a CDR > 0. The autopsy-confirmed group began to decline 3 years prior to receiving a clinical diagnosis of dementia at year 0 (black arrow). Please note that the x-axis (time in years) is only applicable to the Stable group. Including asymptomatic persons with preclinical AD artificially lowers normative values. As a result, means and cutpoints used to detect impairment are too low. (Johnson et al., 2009.)

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE IN DIVERSE POPULATIONS

The tremendous growth of ethnic minorities in the United States and Western Europe places increasing emphasis on the need for cognitive measures and normative data that are appropriate to adequately assess individuals of different ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds. Neuropsychology is in a position to benefit from advances in psychometric methods that move beyond the scrutinizing of between-group test score discrepancies, yet the vast majority of traditional neuropsychological measures commonly in use have not been properly validated for use in minority populations (Manly, 2008; Pedraza and Mungas, 2008). Thus, making diagnostic decisions using neuropsychological tests can be problematic when used on individuals who are not white, have at least two years of college education, are native English speakers, and from at least the midlevels of socioeconomic status (see Manly, 2008 for review). There have been large-scale efforts to develop normative data sets (see Pedraza and Mungas, 2008 for review), but there is still insufficient normative data for the two largest ethnic minorities groups in the United States, blacks and Hispanics. As such, classification accuracy rates for ethnic minorities using traditional normative data sets, especially for difficult diagnoses like prodromal AD, are unacceptable. Pedraza and Mungas (2008) found that using traditional cutoff values of −1.0 standard deviations below the mean for a primarily white sample resulted in classification of 24% to 56% of cognitively normal blacks as cognitively impaired. Results were dramatically improved when using ethnically-specific normative data from Mayo’s Older African American Normative Studies (MOAANS; Lucas et al., 2005). Even when the most likely moderator variables such as age, gender, education, and ethnic backgrounds are taken into account either statistically as covariates or through use of specific normative data sets, other factors can significantly influence cognitive test performance. In a seminal manuscript, Manly and colleagues (Manly et al., 2002) found that using reading level as a proxy for quality of educational attainment largely attenuated differences in neuropsychological test performance between older blacks and whites. These findings appear to extend to blacks with AD. Chin and colleagues (Chin et al., 2012) found that controlling for quality of education using a reading level score, even after including reported years of education as a covariate, attenuated observed differences between blacks and white Non-Hispanics with AD on every neuropsychological test included in the analyses, as well as performance on mental status examinations. Interestingly, the attenuating effect remained after consideration of differences in functional impairment and disease duration, suggesting that use of reading level as a proxy for quality of education is a powerful predictor of neuropsychological performance even in patients with substantial clinical symptoms of AD.

Normative data sets that include mixed ethnicities may provide more accurate performance estimates for ethnic minorities than norms based exclusively on whites. However, grouping people of diverse ethnic backgrounds together may diminish the impact of cultural variables that are unique to particular ethnicities (Lucas et al., 2005). Persons of different ethnic backgrounds may approach the testing situation with different experiences and attitudes that can significantly affect performance. Participants may not be accustomed to the emphasis on speeded performance or have limited familiarity with the wording used in test instructions or test questions (Lucas et al., 2005). Thus, there have been several large-scale attempts to create racially and ethnicity-specific normative data sets in efforts to circumvent these issues; however, this approach has not been without some controversy. Pedraza and Mungas (2008) summarize several arguments against race- or ethnicity-specific normative data sets. Some argue that use of separate norms may ignore underlying factors that contribute to between group differences, such as educational quality. Others argue that use of separate norms reinforces the assumption that race is a biological rather than a socially constructed distinction; another position is that use of separate norms promotes a fundamental misunderstanding about why the discrepancies exist.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Jason Hassenstab reports that neither he nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Research support from the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzhiemer’s Disease Research Center and the National Institutes of Health (K23DK094982).

Dr. Jeffrey Burns reports research support from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG034614, R01AG03367, P30AG035982, U10NS077356, UL1TR000001). Dr. Burns also receives research support for clinical trials from Jannsen, Wyeth, Danone, Pfizer, Baxter, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, and Merck. Dr. Burns serves as a consultant for PRA International, has served as an expert witness for legal cases involving decision-making capacity, and has received royalties from publishing Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment (Wiley Press, 2008) and Dementia: An Atlas of Investigation and Diagnosis (Clinical Publishing, Oxford, England, 2007).

Dr. John C. Morris reports that neither he nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by the following companies: Janssen Immunotherapy, and Pfizer. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for the following companies: Eisai, Esteve, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Program, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Novartis, and Pfizer; and receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

Albert, M. (2008). Neuropsychology of Alzheimer’s disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 88:511–525.

Albert, M.S., DeKosky, S.T., et al. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7:270–279.

Alladi, S., Xuereb, J., et al. (2007). Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 130:2636–2645.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2012). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 8:131–168.

Amieva, H., Phillips, L.H.. (2004). Inhibitory functioning in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 127:949–964.

Barker, W.W., Luis, C.A., et al. (2002). Relative frequencies of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 16:203–212.

Bateman, R.J., Xiong, C., et al. (2012). Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 367:795–804.

Bateman R.J., Wen G., et al. (2007). Fluctuations of CSF amyloid-beta levels: implications for a diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker. Neurol. 68:666–669.

Beach, T.G., Monsell, S.E., et al. (2012). Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71:266–273.

Blessed, G., Tomlinson, B.E., et al. (1968). The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br. J. Psychiatry 114:797–811.

Bondi, M.W., Jak, A.J., et al. (2008). Neuropsychological contributions to the early identification of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol. Rev. 18:73–90.

Braak, H., and Braak, E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82:239–259.

Bruen, P.D., McGeown, W.J., et al. (2008). Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131:2455–2463.

Buckner, R.L. (2004). Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron 44:195–208.

Buckner, R.L., Sepulcre, J., et al. (2009). Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 29:1860–1873.

Carr, D.B., Gray, S., et al. (2000). The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology 55:1724–1727.

Chin, A.L., Negash, S., et al. (2012). Quality, and not just quantity, of education accounts for differences in psychometric performance between African Americans and white non-Hispanics with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 18:277–285.

Cosentino, S., Scarmeas, N., et al. (2008). APOE epsilon 4 allele predicts faster cognitive decline in mild Alzheimer disease. Neurology 70:1842–1849.

Cummings, J.L., Mega, M., et al. (1994). The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44:2308–2314.

de Leon, M.J., Convit, A., et al. (2001). Prediction of cognitive decline in normal elderly subjects with 2-[(18)F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose/positron-emission tomography (FDG/PET). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10966–10971.

Dreyfus, D.M., Roe, C.M., et al. (2010). Autobiographical memory task in assessing dementia. Arch. Neurol. 67:862–866.

Du, A.T., Schuff, N., et al. (2003). Atrophy rates of entorhinal cortex in AD and normal aging. Neurology 60:481–486.

Dubois, B., Feldman, H.H., et al. (2010). Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 9:1118–1127.

Evans, J.G. (1987). The onset of dementia. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 16:271–276.

FDA Approves Amyvid. (2012). PRNewswire 2012: 1–4. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fda-approves-amyvid-florbetapir-f-18-injection-for-use-in-patients-being-evaluated-for-alzheimers-disease-and-other-causes-of-cognitive-decline-146497155.html

Flicker, C., Ferris, S.H., et al. (1991). Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: predictors of dementia. Neurology 41:1006–1009.

Folstein, M.F., Folstein, S.E., et al. (1975). “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12:189–198.

Fotenos, A.F., Snyder, A.Z., et al. (2005). Normative estimates of cross-sectional and longitudinal brain volume decline in aging and AD. Neurology 64:1032–1039.

Freitas, S., Simões, M.R., et al. (2011). Montreal Cognitive Assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. [Epub ahead of print].

Galvin, J.E., Fagan, A.M., et al. (2010). Relationship of dementia screening tests with biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 133:3290–3300.

Galvin, J.E., Roe, C.M., et al. (2005). The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology 65:559–564.

Graff-Radford, N.R., Bolling, J.P., et al. (1993). Simultanagnosia as the initial sign of degenerative dementia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 68:955–964.

Hardy, J., and Selkoe, D.J. (2002). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297:353–356.

Hebert, L.E. (2001). Is the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease greater for women than for men? Am. J. Epidemiology 153:132–136.

Hebert, L.E., Scherr, P.A., et al. (2003). Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch. Neurol. 60:1119–1122.

Hyman, B.T., Phelps, C.H., et al. (2012). National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 8:1–13.

Irizarry, M.C., Jin, S., et al. (2012). Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 69:368–372.

Ismail, Z., Rajji, T.K., et al. (2010). Brief cognitive screening instruments: an update. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 25:111–120.

Jack, C.R., Dickson, D.W., et al. (2002). Antemortem MRI findings correlate with hippocampal neuropathology in typical aging and dementia. Neurology 58:750–757.

Jack, C.R., Jr., Knopman, D.S., et al. (2010). Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 9:119–128.

James, B.D., Wilson, R.S., et al. (2011). Late-life social activity and cognitive decline in old age. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 17:998–1005.

Johnson, D.K., Storandt, M., et al. (2009). Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 66:1254–1259.

Jonsson, T., Atwal, J.K., et al. (2012). A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature 488:96–99.

Kalechstein, A.D., van Gorp, W.G., et al. (1998). Variability in clinical classification of raw test scores across normative data sets. Clin. Neuropsychol. 12:339–347.

Katzman, R. (1976). The prevalence and malignancy of Alzheimer disease: a major killer. Alzheimers Dement. 4:378–380.

Klunk, W.E., Engler, H., et al. (2004). Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 55:306–319.

Knopman, D.S., DeKosky, S.T., et al. (2001). Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 56:1143–1153.

Knopman, D.S., Parisi, J.E., et al. (2003). Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 62:1087–1095.

Larson, E.B., and Langa, K.M. (2012). Aging and incidence of dementia: a critical question. Neurology 78:1452–1453.

Lavery, L.L., Lu, S.-Y., et al. (2007). Cognitive assessment of older primary care patients with and without memory complaints. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 22:949–954.

Lucas, J.A., Ivnik, R.J., et al. (2005). Mayo’s Older African Americans Normative Studies: normative data for commonly used clinical neuropsychological measures. Clin. Neuropsychol. 19:162–183.

Lyketsos, C.G., Lopez, O., et al. (2002). Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA 288:1475–1483.

Manly, J.J. (2008). Critical issues in cultural neuropsychology: profit from diversity. Neuropsychol. Rev. 18:179–183.

Manly, J.J., Jacobs, D.M., et al. (2002). Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 8:341–348.

Mattsson, N., Andreasson, U., et al. (2011). The Alzheimer’s Association external quality control program for cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement. 7:386–395.e6.

McKhann, G., Drachman, D., et al. (1984). Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34:939–944.

McKhann, G.M., Knopman, D.S., et al. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7:263–269.

McNeil, J.K. (1999). Neuropsychological characteristics of the dementia syndrome of depression: onset, resolution, and three-year follow-up. Clin. Neuropsychol. 13:136–146.

Moberg, P.J., and Kniele, K. (2006). Evaluation of competency: ethical considerations for neuropsychologists. Appl. Neuropsychol. 13:101–114.

Morris, J.C. (2006). Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. In: Morris, J.C., Galvin, J.E., and Holtzman, D.M., eds. Handbook of Dementing Illnesses, 2nd Edition. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 191–208.

Morris, J.C. (2012). Revised criteria for mild cognitive impairment may compromise the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Arch. Neurol. 69:700–708.

Morris, J.C. (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43:2412–2414.

Morris, J.C., Weintraub, S., et al. (2006). The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 20:210–216.

Nasreddine, Z.S., Phillips, N.A., et al. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53:695–699.

Nelson, P.T., Alafuzoff, I., et al. (2012). Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71:362–381.

Olin, J.T., Katz, I.R., et al. (2002). Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 10:129–141.

Pedraza, O., and Mungas, D. (2008). Measurement in cross-cultural neuropsychology. Neuropsychol. Rev. 18:184–193.

Perrin, R.J., Fagan, A.M., et al. (2009). Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 461:916–922.

Persons, J.B., and Tompkins, M.A. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral case formulation. In: Eells, T.D., ed. Handbook of Psychotherapy Case Formulation. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 314–339.

Petersen, R.C. (2004). Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 256:183–194.

Petersen, R.C., Smith, G.E., et al. (1995). Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the development of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-impaired individuals. JAMA 273:1274–1278.

Pfeffer, R.I., Kurosaki, T.T., et al. (1982). Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J. Gerontol. 37:323–329.

Price, J.L., Ko, A.I., et al. (2001). Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 58:1395–1402.

Price, J.L., McKeel, D.W., et al. (2009). Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 30:1026–1036.

Price, J.L., and Morris, J.C. (1999). Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 45:358–368.