68 | PATHOGENESIS, DIAGNOSIS, AND TREATMENT OF VASCULAR AND MIXED DEMENTIAS

HELENA CHANG CHUI

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is the second most common contributor to cognitive impairment in late life. Its impact on cognition and behavior is highly variable, depending on the location and extent of vascular brain injury (VBI) in relation to relevant functional networks. A diagnostic approach based on symptomatic profile (e.g., sudden onset, stepwise progression, executive dysfunction, apathy, depression) applies to a typical subset of patients. Alternative approaches based on structural imaging (e.g., MRI) have improved sensitivity for detecting presymptomatic VBI, thereby allowing earlier identification and treatment of vascular risk factors.

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is currently the umbrella term encompassing both mild cognitive impairment and more severe dementia due to vascular brain injury and cerebrovascular disease. It subsumes other appellations including multiinfarct dementia, Binswanger’s syndrome, poststroke dementia, vascular dementia (VD, VaD), ischemic vascular dementia (IVD), subcortical vascular dementia (SVD, SIVD), and vascular cognitive impairment not meeting criteria for dementia (Vascular CIND).

With advancing age, concurrent CVD and neurodegenerative pathologies (e.g., amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, synucleinopathy) become increasingly likely. Alzheimer pathology is associated with progressive loss of cognitive function, whereas the effect of VBI is variable. Sensitive and specific biomarkers for the major pathologies in late life are needed to identify each type of pathology. There is a widely held presumption that reduction of vascular risk will diminish vascular contributions to cognitive impairment.

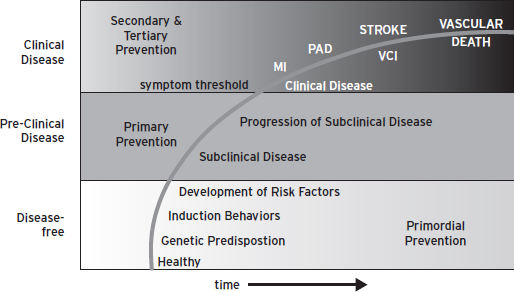

Vascular cognitive impairment represents one manifestation in the larger realm of global vascular risk, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral artery disease (Fig. 68.1) (Sacco, 2007)). Ideally, reduction of global vascular risk should commence before the appearance of symptomatic clinical disease. In the case of VCI, neuroimaging offers a means of identifying the brain at risk. As imaging modalities become even more versatile and dynamic, they may offer new approaches to diagnosis as well as surrogate outcome measures for the prevention and treatment of VCI.

This chapter addresses five empirical questions of clinical relevance to VCI: (1) What is the pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment? (2) How accurate is the diagnosis of VCI? (3) What is the incidence and prevalence of vascular cognitive impairment? (4) What is the relationship between VBI and AD? (5) What is the best way to prevent or treat VCI?

The reader is also referred to a recent consensus statement for health care professionals on vascular cognitive impairment published by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (Gorelick et al., 2011) and the recommendations for Harmonization of Vascular Cognitive Impairment by the National Institute for Neurological Disease and Stroke and the Canadian Stroke Network (Hachinski et al., 2006).

WHAT IS THE PATHOGENESIS OF VASCULAR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT?

Vascular cognitive impairment embodies the construct that vascular risk factors (VRF) lead to cerebrovascular disease (CVD), which leads to parenchymal brain injury (VBI) that leads to cognitive impairment (VCI). There are a plethora of VRFs, CVDs, and mechanisms leading to VBI. There is also tremendous variability in the level of impact VBI imposes on cognition.

VRF→ CVD → VBI→ ?VCI

The most prevalent types of CVD are atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Other less common forms include vasculitis, fibromuscular dysplasia, malformations, and the like. CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) is a relatively rare but pure example of small vessel disease. The cerebrovascular tree may be compromised secondarily by heart disease (e.g., cardiac embolism or heart failure).

Substrate transport and barrier protection are two main functions of the cerebrovascular system. Inadequate delivery of oxygen and glucose to support the basic metabolic needs of brain cells (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendroglia) results in VBI. Narrowing or occlusion of blood vessels leads to ischemic infarction; leakage or rupture of blood vessels to hemorrhage. Clinical investigations focus predominantly on acute and focal stroke syndromes. Less is known about chronic, repeated, or widespread compromise of the cerebral vascular tree or to bidirectional molecular transport across the blood-brain-barrier at the microvascular level.

Ischemia refers to conditions in which tissue perfusion and supply of vital substrate (i.e., oxygen and glucose) are inadequate to support cell metabolism. The balance between supply and demand is influenced by: (1) differences in oxygen and glucose requirements of individual brain cells, (2) regional differences in cerebral blood flow, assuming normal blood content of oxygen and glucose, and (3) the duration of hypoperfusion. Energy requirements are higher for neurons than glia. Blood flow declines as the length of the vessel increases and the radius of the vessel decreases. (Moody et al., 1991) Local cerebral blood flow is lowest in the periventricular and deep white matter—regions perfused by long, narrow, end-arterioles with no collaterals (Moody et al., 1991)

Figure 68.1 Global vascular risk. (Reproduced with Permission from the American Heart Association.)

Two regional patterns of infarction are recognized. When a single artery is narrowed or occluded, the maximal extent of ischemic injury occurs in the center of the corresponding arterial territory. When perfusion pressure drops across several arteries, maximum injury takes place at the border zones between overlapping arteries and at the end zones of terminal arteries. This scenario may occur when: (1) systemic blood pressure drops below autoregulatory reserve, (2) intracranial pressure exceeds mean arterial pressure, or (3) there is severe stenosis of multiple arteries (e.g., hypertensive arteriolosclerosis or amyloid angiopathy). In cases of severe stenotic small artery disease, the periventricular and deep white matter border zones (despite lower oxygen requirements by oligodendroglia and axons) are at risk for chronic ischemia and incomplete infarction.

HETEROGENEITY OF CLINICAL PHENOTYPE

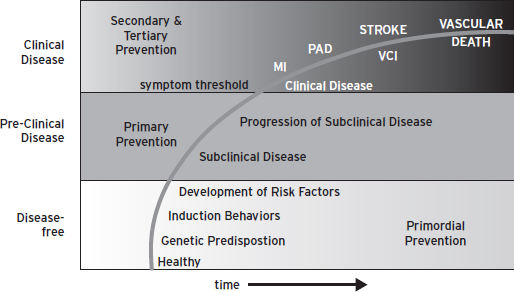

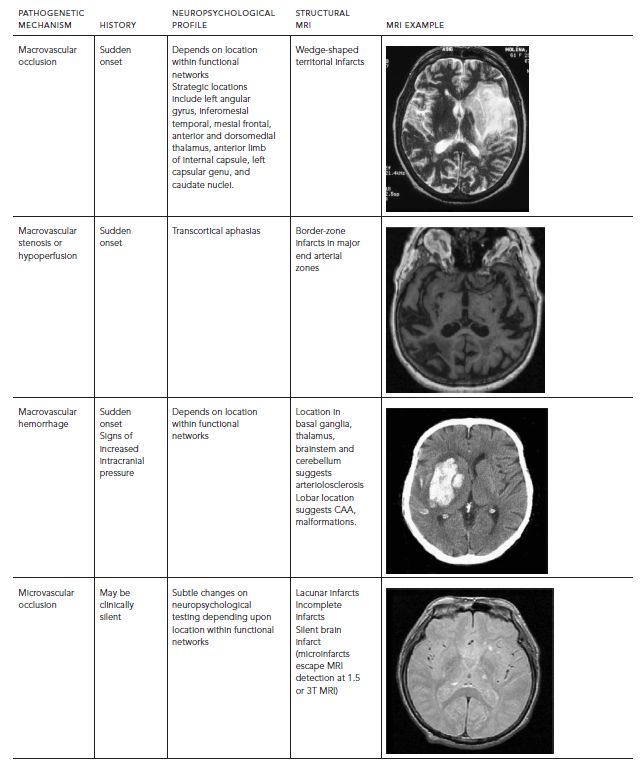

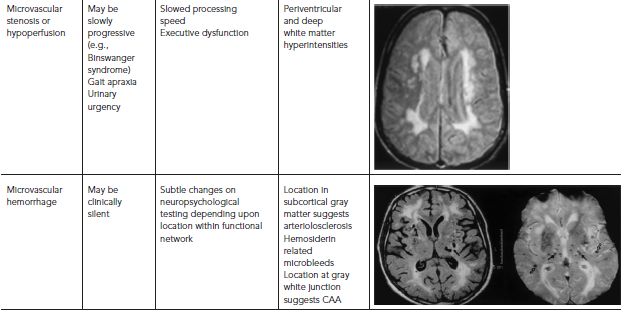

The phenotype of VCI and VaD is highly variable (Table 68.1). In the preimaging era, multiinfarct dementia was described as an abrupt onset and stepwise decline in cognitive function, with focal and patchy deficits in higher cortical function (e.g., aphasia, neglect, visual-spatial, executive). Strategic infarct dementia referred to cases where a single infarct in certain locations (e.g., anterior or dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus; head of the caudate, genu of the internal capsule) resulted in impairment in multiple cognitive domains. Binswanger’s syndrome represents a triad of slowly progressive dementia, early gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence caused by severe arteriolosclerosis of deep penetrating arteries, leading to demyelination of the periventricular and deep cerebral white matter.

The location of VBI is undoubtedly a major determinant of its impact on cognition and behavior. Subcortical lacunes and white matter changes disrupt frontal-subcortical loops and are associated with impairment in executive function. Left middle cerebral artery infarcts impact language faculties, whereas right middle cerebral artery infarcts cause neglect and deterioration of visual-spatial ability. Widespread small vessel disease (e.g., white matter encephalopathy) compromises the attentional matrix and processing speed (Schmidt et al., 2010). Newer imaging techniques such as fMRI and diffusion-weighted tractography promise more precise mapping of VBI onto relevant cognitive and behavior al networks (Duering et al., 2012), and future advances in understanding of the relationship between VBI and VCI.

POSTSTROKE DEMENTIA

Approximately 25–30% of persons meet criteria for dementia three months after hospitalization for first stroke. In addition, the risk of developing dementia in the subsequent one to two years following a stroke is double the general population. In a community-based study of stroke, the prevalence of dementia was 30% immediately after stroke. The incidence of new onset dementia increased from 7% after one year to 48% after 25 years (Kokmen et al., 1996). Long-term mortality is two to six times higher in patients with poststroke dementia, after adjustment of demographic factors, associated cardiac diseases, stroke severity, and stroke recurrence (for review, see Leys et al., 2005). Risk of dementia was higher with increased age, fewer years of education, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, and recurrent stroke (Srikanth et al., 2006). Among neuroimaging findings, silent cerebral infarcts, white matter changes, and global and medial temporal lobe atrophy are associated with increased risk of poststroke dementia (Leys et al., 2005). Left hemisphere, anterior and posterior cerebral artery distribution, multiple infarcts, and strategic infarcts have been associated with greater risk of dementia (Allan et al., 2011). Thus, differential risk for cognitive impairment is not straightforward, but appears to be related to number, location, underlying type of vasculopathy, coexisting neurodegenerative processes, and cognitive reserve.

TABLE 68.1. VCI phenotype depends on pathogenetic mechanism and location of VBI

SILENT BRAIN ISCHEMIA

Structural MRI reveals evidence of asymptomatic VBI, including silent brain infarcts (SBI), white matter hyperintensities (WMH), and microbleeds. The designation subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) describes cases of WMH and SBI located in subcortical gray and white matter. Gradient echo MR sequences may give evidence of small microbleeds, another often asymptomatic manifestation of VBI.

The prevalence of SBI on MRI in community-based samples varies between 5.8% and 17.7% with an average of 11%, depending on age, ethnicity, presence of comorbidities, and imaging techniques (Das et al., 2008). In the Framingham study, prevalence of SBI between the fifth and seventh decades of life is approximately 10%, but increases rapidly in the eighth decade to 17% and in the ninth decade to nearly 30%. Silent brain infarcts are most often located in the basal ganglia (52%), followed by other subcortical (35%) and cortical areas (11%) (Das et al., 2008). Risk factors for SBI are generally the same as those for clinical stroke (Das et al., 2008; Prabhakaran et al., 2008)

White matter hyperintensities are even more common and are generally present in most individuals older than 30 years of age (Decarli et al., 2005), increasing steadily in extent with advancing age. Also, WMH share risk factors with stroke (Jeerakathil et al., 2004). Age-specific definitions of extensive WMH can be created (Massaro et al., 2004) and prove useful in defining risk for VCI in a community cohort (Debette et al., 2010).

Numerous studies have examined the cross-sectional relationship between MRI evidence of VBI and cognitive ability. A recent review (Mayda and DeCarli, 2009) of a large number of epidemiological studies summarizes cognitive and behavioral effects of both SCI and WMH on cognition. The presence of SBI more than doubles the risk of dementia and risk of stroke (Vermeer, Den Heijer et al., 2003a; Vermeer, Prins et al., 2003b). WMH are associated with decline in the modified Mini-Mental State Exam and the digit symbol substitution test (Longstreth et al., 2002, 2005), incident MCI, dementia, and death (Mayda and DeCarli, 2009).

Recent data suggests that progression of WMH is an even better predictor of persistent cognitive impairment than baseline white matter lesion burden (Schmidt et al., 1999; Silbert et al., 2009). In the Leukoaraiosis and DISability (LADIS) study the, severity of white matter lesions (WML) was associated with diminished executive function, depression, decreased balance and more falls, and urinary incontinence over 10 years of follow-up (Table 68.2) (Poggesi et al., 2011). Longitudinal quantitative MR studies in a relatively healthy elderly cohort showed that acceleration of WMH burden preceded the onset of mild cognitive impairment by a decade (Silbert et al., 2012).

SUBCORTICAL VASCULAR DEMENTIA

At a certain threshold, subcortical ischemic vascular disease becomes clinically symptomatic. The cognitive profile associated with subcortical vascular dementia (SVD) is said to be characterized by greater impairment in executive compared to memory domains, as well as apathy and depression (Roman et al., 2002). Indeed in CADASIL, a relatively pure form of SVD caused by a relatively rare autosomal dominant mutation in Notch 3 gene (Dichgans et al., 1998), neuropsychological testing shows impairments in tests sensitive to speed and executive function (verbal fluency, digit symbol substitution, trails B) (Peters et al., 2005). In CADASIL, cognitive decline correlated with increased mean diffusivity, progressive atrophy, and infarct volume, rather than WMH or microbleeds (Jouvent et al., 2007). Among neuropathologically-defined cases followed prospectively with psychometrically-matched measures of executive and memory function, SIVD cases showed relatively similar levels of impairment in memory and executive function (only 9% showed predominant executive dysfunction) (Reed et al., 2004). In contrast, 67% of AD cases and 64% of mixed cases presented with a profile of predominant memory impairment. This autopsy study suggests that although executive dysfunction is common, predominant dysexecutive profile (i.e., greater than memory impairment) may not be a sensitive diagnostic marker for sporadic SVD.

TABLE 68.2. Main findings from the ladis study concerning the role of neuroimaging features in clinical aspects

| CLINICAL CORRELATES | MRI LESIONS (PARAMETER) | RESULTS |

| Functional status | Baseline severe WMC | – Association with worse functional status – Independent predictor of disability |

| Cognition | Baseline severe WMC | – Association with worse score on MMSE and ADAS – Association with worse cognitive performances on global tests of cognition, executive functions, speed and motor control, attention, naming and visuoconstructional praxis – Independent predictor of dementia and cognitive impairment |

| Progression of WMC | – Association with decrease in executive function score | |

| Number of lacunar infarcts | – Association with worse score on MMSE and ADAS | |

| Location of lacunar infarcts | – Thalamus location associated with worse cognitive performances (MMSE and compound scores for speed and motor control, and executive functions) | |

| Number of new lacunes | – Association with deterioration in executive functions, speed and motor control | |

| SIVD1 | – Independent predictor of decline in cognitive performances and of dementia | |

| MTA severity | – Association with mild cognitive deficits (MMSE <26); additional effect with severe WMC – Predictor of Alzheimer’s disease |

|

| Corpus callosum atrophy | – Association with worse cognitive performances – Regional association with cognitive performances: anterior with deficits of attention and executive functions, isthmus sub region with semantic verbal fluency – Independent predictor of dementia and motor impairment |

|

| Changes in mean diffusivity of normal appearing white matter | – Association with cognitive dysfunction | |

| Mood | Baseline WMC severity | – Association with depressive symptoms – Independent predictor of depressive mood and depressive episodes |

| WMC location | – Deep WMC associated with depressive symptoms – Frontal and temporal regions associated with depressive symptoms |

|

| Location of lacunar infarcts | – Association of basal ganglia lesions with depressive symptoms | |

| Motor performances | Baseline severe WMC | – Association with worse motor performances – Association with falls and balance disturbances |

| WMC location | – Periventricular and deep frontal WMC associated with falls – Deep frontal WMC associated with balance disturbances |

|

| Urinary problems | Baseline severe WMC | – Association with urinary urgency |

HOW ACCURATE IS THE DIAGNOSIS OF VASCULAR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT?

CLINICAL CRITERIA

Diagnostic criteria for VCI have evolved as new imaging modalities have come on line. In 1975, the likelihood that dementia was caused by multiple infarctions (vs. primary neuronal degeneration), was operationalized using the Hachinski Ischemic Score (Hachinski et al., 1975). Points were assigned based on features of the clinical history and examination (e.g., abrupt onset, stepwise progression, emotional incontinence, focal neurologic signs and symptoms) associated with clinical stroke.

The threshold for detecting VBI was lowered dramatically with the arrival of MRI in the 1980s. Numerous second generation criteria for VaD appeared, incorporating results of neuroimaging: DSM, ICD, ADDTC, and NINDS-AIREN criteria. These criteria share several elements in common, but differ in operational definition: (1) requirement for cognitive impairment, (2) evidence of vascular brain injury, and (3) operational criteria linking VBI to cognitive impairment.

A diagnosis of probable VaD by NINDS-AIREN criteria requires a temporal association between the onset of stroke and cognitive decline (Roman et al., 1993). Evidence of two infarcts outside of the cerebellum suffices for a diagnosis of probable IVD by ADDTC criteria (Chui et al., 1992; Lopez et al., 2005) The number of subjects classified as VCI may differ two- to fourfold depending upon diagnostic criteria, (Knopman et al., 2002; Lopez et al., 2003, 2005) with NINDS-AIREN criteria being most conservative and ADDTC criteria most liberal. ICD-10 and DSM-5 feature minor variations on these past themes.

Clinical criteria have also been proposed for subtypes of VCI, including subcortical vascular dementia (SVD) (Erkinjuntti et al., 2000) and Binswanger syndrome (Bennett et al., 1990). Recently, criteria have been proposed for the clinical diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment not meeting criteria for dementia (Vascular CIND) (Gorelick et al., 2011).

In evidence-based medicine, accuracy of clinical criteria is measured against a reference standard. Accuracy of clinical criteria for AD is assessed against a neuropathological gold standard (e.g., CERAD criteria, NIA-Reagan criteria). In the case of VCI, there is still no agreed upon gold standard for the diagnosis. Bearing these limitations in mind, comparisons between clinical criteria versus neuropathological criteria for VaD (e.g., evidence of VBI in three lobes of the cerebral hemisphere) show limited sensitivity, but high specificity. Positive likelihood ratios range from 3 to 5 (Gold et al., 2002), wherein modest changes in pre- to posttest probability may be seen.

NEUROPATHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

Although neuropathology excels in the characterization of CVD and VBI, there is lack of consensus about how to apportion cognitive impairment to evidence of VBI, AD, or other pathologies found on neuropathological evaluation. Thus, as mentioned in the preceding, there are no consensus criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of VCI (Hachinski et al., 2006). On the other hand, guidelines to harmonize the neuropathological evaluation for VBI have been published (Hachinski et al., 2006), hopefully laying the foundation for future diagnostic paradigms.

Neuropathological examination provides valuable information regarding the presence and severity of CVD, VBI, neurodegenerative and mixed pathologies. Neuropathologic evaluation elucidates the type and severity of CVD (e.g., atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, amyloid angiopathy), and the severity, location, and size of VBI, including microinfarcts (too small to be seen by current 1.5 or 3 tesla MRI). Neuropathological examination greatly enhances our ability to identify cases with relatively pure versus mixed vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies by disclosing the presence and severity of amyloid plaques, tau-associated neurofibrillary degeneration, alpha-synuclein associated Lewy bodies, and TDP-43 intracytoplasmic inclusions. Better methods are needed to quantify the severity of diffuse white matter lesions, multiple microinfarcts, which are hallmarks of VBI, as well as synaptic loss, which may be a common underlying denominator of cognitive decline.

DYNAMIC AND FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING: FUTURE ADVANCES IN DIAGNOSIS?

The advent of new structural and dynamic MRI sequences (e.g., diffusion tensor, fMRI, perfusion) promises additional advances for the detection and characterization of VCI. Diffusion tensor imaging/tractography provides a measure of white matter integrity. Resting fMRI provides a noninvasive measure of functional brain connectivity. Arterial spin labeling allows noninvasive and readily available measure of cerebral perfusion (compared with contrast arteriography or H2(15O) PET. This may advance characterization of vasoreactivity in response to physiologic stressors (e.g., hypercapnea, orthostasis). With these additional advances in neuroimaging, we anticipate new approaches to the prevention and diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment that include measures of vascular endothelial cell function and earlier recognition of the brain at risk.

WHAT IS THE INCIDENCE OF VCI AND MIXED VBI/AD?

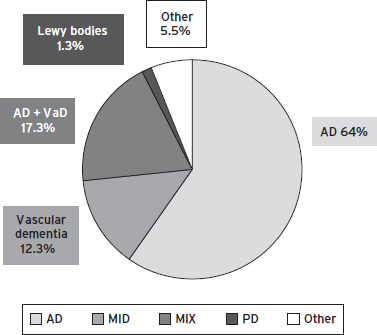

Vascular brain injury is the second most common cause of dementia, after Alzheimer neurodegeneration. In the Cardiovascular Health Study 69% of cases with incident dementia were classified as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), 11% as vascular dementia (VaD), 16% as both, and 4% as other types of dementia (Fig. 68.2) (Lopez et al., 2003). There is considerable variability in the incidence rates of vascular dementia (VaD) reported in the literature, depending upon methodological differences (e.g., diagnostic criteria, neuroimaging, neuropathology), threshold for cognitive impairment, as well as demography (e.g., age, ethnicity, education, and gender). Although neuroimaging increases the detection of VBI (McKhann et al., 2011), the cost may become prohibitive for large-scale epidemiology studies. Neuropathology improves the diagnosis of AD, VaD, and especially mixed pathology. Few studies have set the threshold for diagnosis of VCI at the level of mild cognitive impairment.

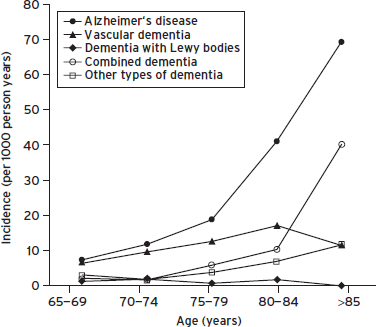

The Hisayama study (Matsui et al., 2009) stands out as a rare population-based study in Japan with a high autopsy rate (80%), where diagnostic classifications were informed by clinical, neuroimaging, and neuropathologic findings. Between ages 80 to 85 years, the annual incidence of AD, VD, and mixed AD/VD were approximately 4, 2, and 1 per 100 person years, respectively; after age 85, the rates were 7, 1, and 4 (Fig. 68.3). Thus, the incidences of AD, mixed dementia, and other types of dementia (but not VD) rose with increasing age, particularly after the age of 85 years (Matsui, et al., 2009). Similar incidence rates of AD and VaD (2/100 person years and 1/100 person years at age 85) were reported in Conselice, Italy, based on clinical diagnostic classifications (i.e., did not include mixed cases) (Ravaglia et al., 2005). Lower rates for VaD were reported in Rochester, MN (0.3 per 100 person years at age 85 years), as well as in earlier European metaanalysis without neuroimaging studies (Fratiglioni et al., 2000), which also did not include mixed cases.

Figure 68.2 Causes of senile dementia.

In a poststroke dementia study (Allan et al., 2011), the incidence of delayed dementia was calculated to be 6.32 cases per 100 person years. The most robust predictors of dementia included low baseline Cambridge Cognitive Examination executive function and memory scores, Geriatric Depression Scale score and three or more cardiovascular risk factors. Autopsy findings suggested that 75% or more of the demented stroke survivors met criteria for VaD. But demented subjects tended to exhibit marginally greater neurofibrillary pathology, including tauopathy and Lewy bodies and microinfarcts, than nondemented stroke survivors, again underscoring the relevance and contributions of mixed pathologies.

Figure 68.3 Incidence of dementia subtypes. (Reproduced with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.)

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CVD AND AD?

MIXED VASCULAR BRAIN INJURY/AD PATHOLOGIES

Mixed vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies are commonly found in community-based autopsy studies. In the Honolulu Asia Aging Study of Japanese-American men, 25% of dementia cases had mixed pathologies, compared with 57% with primarily AD, and 53% with primarily microinfarcts (White et al., 2002). In the Religious Orders Study (Schneider et al., 2007) and community-based elderly autopsies series (Schneider et al., 2009), mixed pathologies was more common than AD or infarcts alone. Among the first 209 autopsy cases from the Cognitive Function in Aging Study (CFAS), both cerebrovascular (78%) and Alzheimer type (70%) pathologies were common.

The frequent concurrence of VBI and AD in the same person, especially with advancing age, prompts several questions. Does the concurrence of two distinct pathologies (VBI and AD) represent the chance occurrence of two common age-associated pathologies? How do CVD and AD influence or interact with each other, in terms of pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Do vascular risk factors increase the risk of AD? Can treatment of vascular risk factors prevent AD?

In the following discussions of CVD and AD we refer to arteriosclerosis, the most prevalent form of CVD, and to VRF for stroke associated with arteriosclerosis (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking). We do not include cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a common vasculopathy, which shares with parenchymal AD pathology a strong association with the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (Smith and Greenberg, 2009).

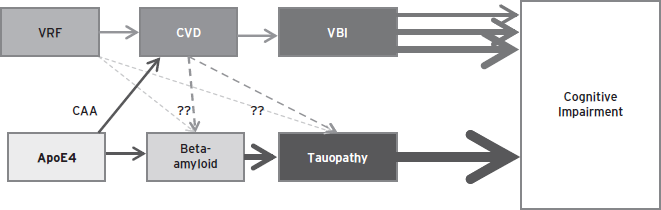

PATHOGENESIS OF VBI AND AD: CROSSING OR PARALLEL PATHWAYS?

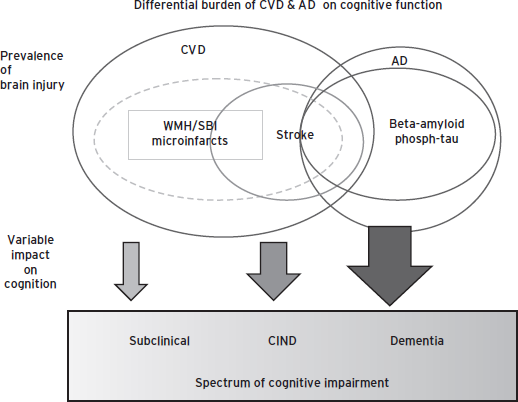

Recently, the concept that risk factors for arteriosclerosis are also risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease has gained traction. This hypothesis has been driven largely by some (Qiu et al., 2010; Reitz et al., 2010), but not all (Ronnemaa et al., 2011), epidemiologic studies wherein recognized risk factors for arteriosclerosis (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and aggregated vascular risk factors) are associated with increased risk of incident clinically-diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. These data suggest two possibilities: Are vascular risk factors also risk factors for plaques and tangles, or are they promoting subclinical VBI that make symptoms of dementia appear earlier? (Fig. 68.4).

Figure 68.4 Impact of vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease on cognition.

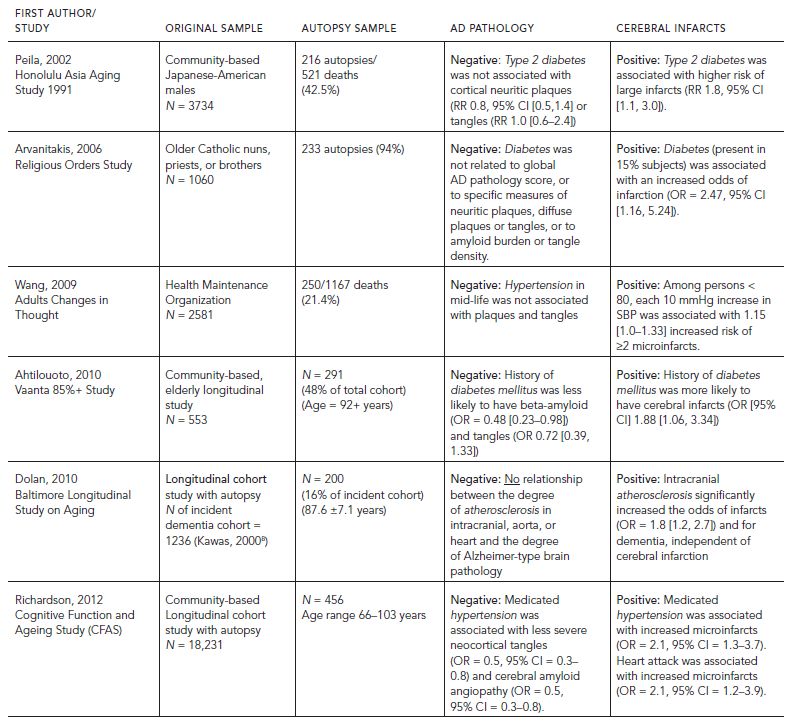

Positive associations between intracranial atherosclerosis and severity of plaques and tangles have been reported from several Alzheimer’s disease brain banks (Beach et al., 2007; Honig et al., 2005). However, in a recent evidence-based review (Chui et al., 2012), no representative, prospective autopsy studies have shown significant positive associations between diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or intracranial atherosclerosis and AD pathology (i.e., plaques or tangles) (Table 68.3). The authors concluded that at the present time, there is no compelling evidence to show that vascular risk factors increase AD pathology. The alternate, but also unproven possibility remains that arteriosclerosis promotes subclinical VBI, thereby increasing the likelihood of dementia and in some cases making symptoms present earlier.

It is difficult to determine to what extent cognitive impairment may be caused by stroke versus concomitant AD. Estimates of the proportion of patients with poststroke dementia who also have underlying AD vary widely between 19% and 61%. (Leys et al., 2005) About 15% to 30% of persons with poststroke dementia have a history of dementia before stroke (Pohjasvaara et al., 1999; Cordoliani-Mackowiak et al., 2003) and approximately one-third have significant medial temporal atrophy. In the Lille study, the incidence of dementia three years after stroke was significantly greater in those patients with versus without medial temporal atrophy (81% vs. 58%) (Cordoliani-Mackowiak et al., 2003). Taken together, these finding suggest that-approximately one-third of cases AD may contribute to dementia in patients poststroke.

COGNITIVE IMPACT OF VBI AND AD: ADDITIVE OR SYNERGISTIC?

Converging evidence suggests an additive effect of VBI and AD on cognitive function. In the Cognitive Function in Aging Study some degree of neocortical neurofibrillary pathology was found in 61% of demented (N = 100) and 34% of non-demented individuals (N = 109). Vascular lesions were equally common in both groups, although the proportion with multiple vascular lesions was higher in the demented group (46% vs. 33%). In the Religious Order study (N = 153), each unit of AD pathology increased the odds of dementia by 4.40-fold and the presence of one or more infarctions independently increased the odds of dementia by 2.80-fold. There was no interaction between AD pathology and infarctions to further increase the likelihood of dementia (p = 0.39) (Schneider et al., 2004). In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Autopsy Program (BLSA) (N = 179), a logistic regression model indicated that AD pathology alone accounted for 50% of the dementia, and hemispheral infarcts alone or in conjunction with AD pathology accounted for 35% (Troncoso et al., 2008). In a longitudinal study of SIVD, severity of AD pathology and presence of hippocampal sclerosis were the strongest predictors of dementia, whereas subcortical VBI exerted a significantly weaker effect (Chui et al., 2006). In the Honolulu Asia Aging Study, microinfarcts and neurofibrillary tangles were the strongest predictors of cognitive status, with microinfarcts having a greater impact in persons without dementia and tangles exerting the stronger influence in dementia (Launer et al., 2011).

Taken together, these findings suggest a model in which the attributable risk of cognitive impairment is the sum of various pathological lesions (including aging, and vascular and neurodegenerative changes) weighted by their differential impact on cognition minus cognitive reserve:

CI = age + (A*AD + B*VBI + C*Other pathology . . . )

– (A1 *Edu + A2* Other reserve)

Alzheimer’s disease pathology has a relatively large and consistent impact A on cognition, whereas VBI has a highly variable impact B on cognition, depending on location, size, and number. Strategic infarcts by definition are associated with high impact on cognition. Of interest, microinfarcts (which may be numerous and widespread) also appear to contribute relatively greater deleterious effects (Fig. 68.5).

WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO PREVENT OR TREAT VASCULAR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT?

At the present time, there are no medications specifically

approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the symptomatic treatment of VCI. Clinical trials of cognitive-enhancing medications approved for the treatment of AD (e.g., acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine) have also shown beneficial effects in subjects with VCI (Kavirajan and Schneider, 2007). But it was unclear whether these beneficial effects result from the concomitant presence of AD pathology or specific effects on VCI. Vascular brain injury is commonly associated with depression (Alexopoulos et al., 1997; Kales et al., 2005). Treatment with antidepressant medications (e.g., selective serotonin uptake inhibitors) is warranted, although responses in patients with VBI may be less gratifying (Sheline et al., 2010).

TABLE 68.3. Correlations between CVD and AD: longitudinal aging cohort with autopsy

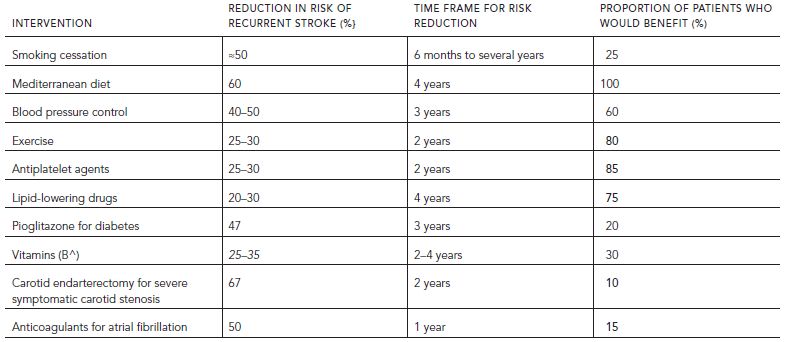

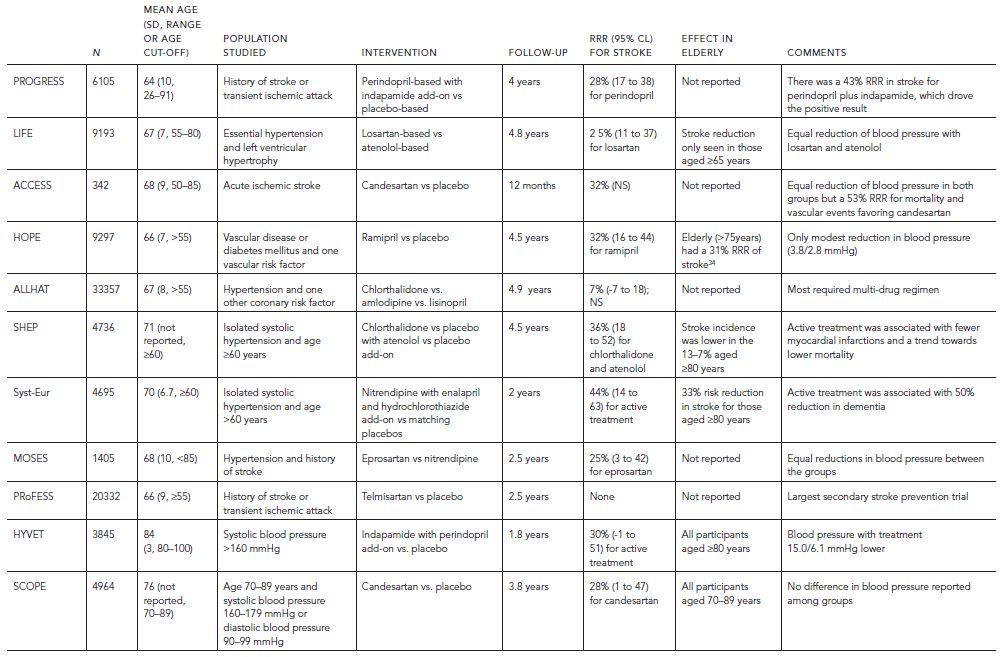

Overwhelming evidence indicates that early identification and reduction of VRF is effective for the primary or secondary prevention of stroke. Interventions include antihypertensives, statins, glycemic control, antiplatelet medications, revascularization procedures, and lifestyle modification (smoking cessation, exercise, and diet education). Recommendations for primary prevention (American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Guidelines [Goldstein et al., 2011]) and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (Table 68.4) (Acciarresi et al., 2011; Ovbiagele, 2010; Spence, 2010) have been recently reviewed. Among the very elderly, targeted reduction of vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension and hyperlipidemia) through clinical trials shows significant reductions in risk of stroke, although the benefits are not as large as among younger subjects (Table 68.5) (Sanossian and Ovbiagele, 2009).

Figure 68.5 Differential burden of CVD and AD on cognitive function.

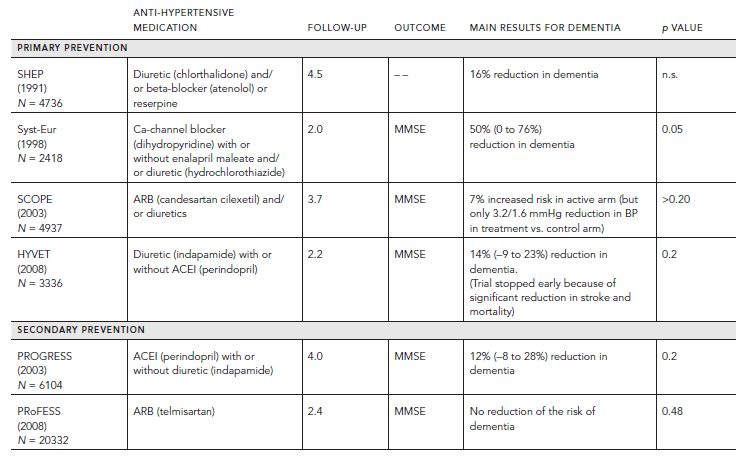

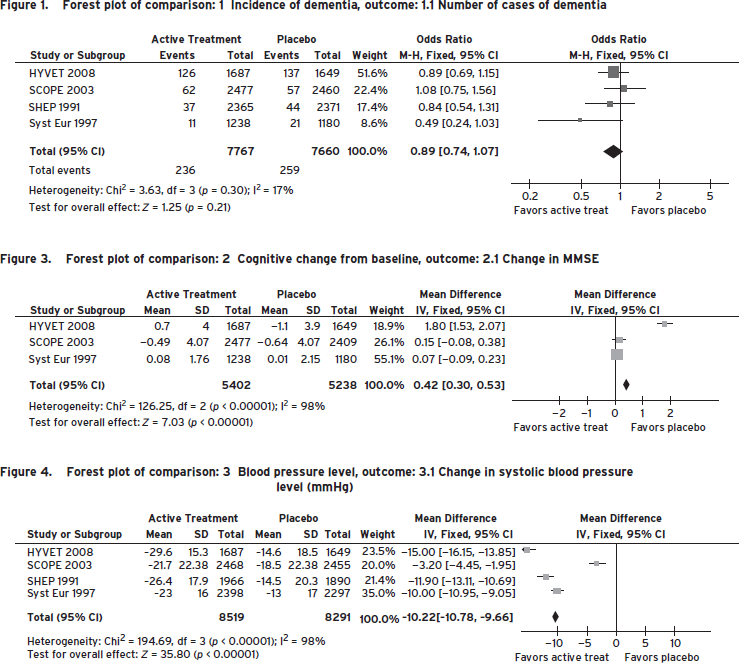

Based on our understanding of the pathogenesis of VCI, it stands to reason that risk reduction for stroke will generalize to risk reduction for VCI. In fact, whereas the benefits of antihypertensive treatment in reducing the risk of stroke are compelling, evidence-based data vis-à-vis reduction of VCI is relatively modest. Only small reductions in VCI were observed in a metaanalysis of four double-blind placebo-controlled primary prevention trials of antihypertensive medication (i.e., SHEP, Syst-Eur, HYVET, and SCOPE) (Table 68.6; Fig. 68.7) (McGuinness et al., 2009 (2009)). In two anti-hypertensive trials for the secondary prevention of stroke, only modest differences in MMSE were noted in the active versus placebo arms (i.e., PROGRESS and PRoFESS) (Diener et al., 2008; “Randomised trial . . . ,” 2001). This lack of evidence may reflect limitations in clinical trial design, because studies have been relatively short in duration (two–four years), have employed insensitive cognitive outcome measures (i.e., Mini-Mental State Examination), and have been stopped early because of effective but preemptive reduction of other vascular endpoints.

TABLE 68.4. Importance of secondary stroke interventions

TABLE 68.5. Randomized clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs for prevention of stroke in the elderly

TABLE 68.6. Primary and secondary prevention trials that included a cognition outcome measure

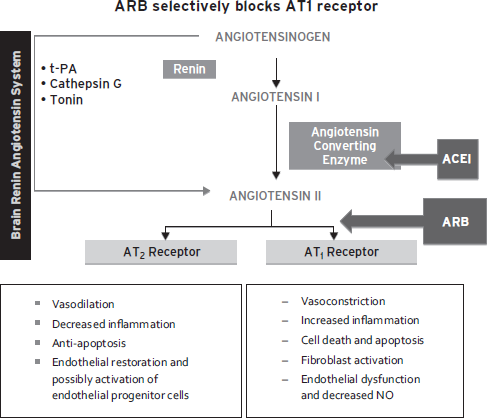

Figure 68.6 ARB selectively blocks AT1 receptor. (Reproduced with permission from The Cochrane Collaboration.)

The Joint National Commission-7 (Chobanian et al., 2003) recommended more intensive blood pressure (BP) targets for patients with diabetes or kidney disease. The opposite may be true for individuals with extensive leukoaraiosis, in whom more liberal BP targets may be appropriate. Patients who have severe small-artery disease and compromised autoregulatory reserve may be at increased risk for ischemia, if blood pressure is abruptly lowered by postural changes (orthostatic hypotension) (Mehagnoul-Schipper et al., 2001) or overly aggressive antihypertensive treatment. In a metaanalysis of 11 clinical trials, achieving an SBP less than 130 mmHg compared with 130 to 139 mmHg appears to provide additional stroke protection only among people with risk factors but no established cardiovascular disease (Lee et al., 2012). Higher risk of hemorrhage has been reported with administration of tPA (Palumbo et al., 2007) or anticoagulant drugs (Cervera et al., 2012) in patients with leukoaraiosis. Additional research using dynamic measures of vasoreactivity, cerebral perfusion, and integrity of the blood–brain barrier, may help set BP parameters for special subgroups of patients with significant white matter disease.

It is possible that beyond their effects on lowering blood pressure, angiotensin receptor blockers may be have selective benefits for VCI. Angiotensin receptor blockers selectively block angiotensin receptor type 1 (AT1) and increase relative activation of AT2 receptors, which may protect endothelial cells and neurons (Fig. 68.6) (Armario and de la Armario and de la Sierra, 2009; Hajjar et al., 2012; Horiuchi et al., 2010). In contrast, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors decrease activation of both AT1 and AT2 receptors. In a recent pilot study, candesartan was associated with greater improvement in tests sensitive to executive dysfunction than hydrochlorothiazide or lisinopril (Hajjar et al., 2012). Protection of endothelial and neuronal cells may represent promising new strategies to ameliorate VCI.

Figure 68.7 Forest plot of comparison. (Reproduced with permission from McGuinness, B., Todd, S., Passmore, P., and Bullock, R. (2009). Blood pressure lowering in patients without prior cerebrovascular disease for prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia [Meta-Analysis Review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (4), CD004034 Courtesy of Ihab Hajjar.)

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Chui has no conflicts of interest to disclose. She is funded by NIA only. Grant Support: NIH (P01-AG12435; P50 AG05142).

REFERENCES

Acciarresi, M., De Rango, P., et al. (2011). Secondary stroke prevention in women. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Womens Health 7(3):391–397.

Alexopoulos, G.S., Meyers, B.S., et al. (1997). “Vascular depression” hypothesis. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 54(10):915–922.

Allan, L.M., Rowan, E.N., et al. (2011). Long term incidence of dementia, predictors of mortality and pathological diagnosis in older stroke survivors. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Brain 134(Pt 12):3716–3727.

Armario, P., and de la Sierra, A. (2009). Antihypertensive treatment and stroke prevention: are angiotensin receptor blockers superior to other antihypertensive agents? [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 3(3):197–204.

Beach, T.G., Wilson, J.R., et al. (2007). Circle of Willis atherosclerosis: association with Alzheimer’s disease, neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Acta Neuropathol. 113(1):13–21.

Bennett, D.A., Wilson, R.S., et al. (1990). Clinical diagnosis of Binswanger’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 53(11):961–965.

Cervera, A., Amaro, S., et al. (2012). Oral anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. [Review]. J. Neurol. 259(2):212–224.

Chobanian, A.V., Bakris, G.L., et al. (2003). Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. [GuidelinePractice Guideline Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Hypertension 42(6):1206–1252.

Chui, H.C., Victoroff, J.I., et al. (1992). Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the State of California Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers. Neurology 42(3 Pt 1):473–480.

Chui, H.C., Zarow, C., et al. (2006). Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann. Neurol. 60(6):677–687.

Chui, H.C., Zheng, L., et al. (2012). Vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: are these risk factors for plaques and tangles or for concomitant vascular pathology that increases the likelihood of dementia? An evidence-based review. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 4(1):1.

Cordoliani-Mackowiak, M.A., Henon, H., et al. (2003). Poststroke dementia: influence of hippocampal atrophy. Arch. Neurol. 60(4):585–590.

Das, R.R., Seshadri, S., et al. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of silent cerebral infarcts in the Framingham offspring study. Stroke 39(11):2929–2935.

Debette, S., Beiser, A., et al. (2010). Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke 41(4):600–606.

Decarli, C., Massaro, J., et al. (2005). Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the Framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiol. Aging 26(4):491–510.

Dichgans, M., Mayer, M., et al. (1998). The phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL: clinical findings in 102 cases. Ann. Neurol. 44(5):731–739.

Diener, H.C., Sacco, R.L., et al. (2008). Effects of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel and telmisartan on disability and cognitive function after recurrent stroke in patients with ischaemic stroke in the Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) trial: a double-blind, active and placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 7(10):875–884.

Duering, M., Righart, R., et al. (2012). Incident subcortical infarcts induce focal thinning in connected cortical regions. Neurology 79(20):2025–2028.

Erkinjuntti, T., Inzitari, D., et al. (2000). Research criteria for subcortical vascular dementia in clinical trials. J. Neural. Transm. Suppl. 59:23–30.

Fratiglioni, L., Launer, L.J., et al. (2000). Incidence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. [Multicenter Study]. Neurology 54(11 Suppl 5):S10–S15.

Gold, G., Bouras, C., et al. (2002). Clinicopathological validation study of four sets of clinical criteria for vascular dementia. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am. J. Psychiatry 159(1):82–87.

Goldstein, L.B., Bushnell, C.D., et al. (2011). Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. [Practice Guideline]. Stroke 42(2):517–584.

Gorelick, P.B., Scuteri, A., et al. (2011). Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 42(9):2672–2713.

Hachinski, V., Iadecola, C., et al. (2006). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke 37(9):2220–2241.

Hachinski, V.C., Iliff, L.D., et al. (1975). Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Arch. Neurol. 32(9):632–637.

Hajjar, I., Hart, M., et al. (2012). Effect of antihypertensive therapy on cognitive function in early executive cognitive impairment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. [Comparative Study Letter Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Arch. Intern. Med. 172(5):442–444.

Honig, L.S., Kukull, W., et al. (2005). Atherosclerosis and AD: analysis of data from the US National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Neurology 64(3):494–500.

Horiuchi, M., Mogi, M., et al. (2010). The angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the brain. [Review]. JRAAS 11(1):1–6.

Jeerakathil, T., Wolf, P.A., et al. (2004). Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham Study. Stroke 35(8):1857–1861.

Jouvent, E., Viswanathan, A., et al. (2007). Brain atrophy is related to lacunar lesions and tissue microstructural changes in CADASIL. Stroke 38(6):1786–1790.

Kales, H.C., Maixner, D.F., et al. (2005). Cerebrovascular disease and late-life depression. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Review]. Am. J. Geriat. Psychiat. 13(2):88–98.

Kavirajan, H., and Schneider, L.S. (2007). Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 6(9):782–792.

Knopman, D.S., Rocca, W.A., et al. (2002). Incidence of vascular dementia in Rochester, Minn, 1985–1989. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Arch. Neurol. 59(10):1605–1610.

Kokmen, E., Whisnant, J.P., et al. (1996). Dementia after ischemic stroke: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota (1960–1984). Neurology 46(1):154–159.

Launer, L.J., Hughes, T.M., et al. (2011). Microinfarcts, brain atrophy, and cognitive function: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study Autopsy Study. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural]. Ann. Neurol. 70(5):774–780.

Lee, M., Saver, J.L., et al. (2012). Does achieving an intensive versus usual blood pressure level prevent stroke? [Comparative Study Meta-Analysis]. Ann. Neurol. 71(1):133–140.

Leys, D., Henon, H., et al. (2005). Poststroke dementia. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Lancet Neurol. 4(11):752–759.

Longstreth, W.T., Jr., Arnold, A.M., et al. (2005). Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of worsening white matter on serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke 36(1):56–61.

Longstreth, W.T., Jr., Dulberg, C., et al. (2002). Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of brain infarcts defined by serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke 33(10):2376–2382.

Lopez, O.L., Kuller, L.H., et al. (2005). Classification of vascular dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Neurology 64(9):1539–1547.

Lopez, O.L., Kuller, L.H., et al. (2003). Evaluation of dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Neuroepidemiology 22(1):1–12.

Massaro, J.M., D’Agostino, R.B., Sr., et al. (2004). Managing and analysing data from a large-scale study on Framingham offspring relating brain structure to cognitive function. [Comparative Study Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Stat. Med. 23(2):351–367.

Matsui, Y., Tanizaki, Y., et al. (2009). Incidence and survival of dementia in a general population of Japanese elderly: the Hisayama study. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 80(4):366–370.

Mayda, A.V., and DeCarli, C. (2009). Vascular cognitive impairment: prodrome to VaD? In: Wahlund, L.-O., Erkinjuntti, T., and Gauthier, S., eds. Vascular Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–31.

McGuinness, B., Todd, S., et al. (2009). Blood pressure lowering in patients without prior cerebrovascular disease for prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia. [Meta-Analysis Review]. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (4):CD004034.

McKhann, G.M., Knopman, D.S., et al. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7(3):263–269.

Mehagnoul-Schipper, D.J., Colier, W.N., et al. (2001). Reproducibility of orthostatic changes in cerebral oxygenation in healthy subjects aged 70 years or older. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Clin. Physiol. 21(1):77–84.

Moody, D.M., Santamore, W.P., et al. (1991). Does tortuosity in cerebral arterioles impair down-autoregulation in hypertensives and elderly normotensives? A hypothesis and computer model. [In Vitro]. Clin. Neurosurg. 37:372–387.

Ovbiagele, B. (2010). Optimizing vascular risk reduction in the stroke patient with atherothrombotic disease. [Review]. Med. Princ. Pract. 19(1):1–12.

Palumbo, V., Boulanger, J.M., et al. (2007). Leukoaraiosis and intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolysis in acute stroke. Neurology 68(13): 1020–1024.

Peters, R., Beckett, N., et al. (2008). Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 7(8):683–689.

Peters, N., Opherk, C., et al. (2005). The pattern of cognitive performance in CADASIL: a monogenic condition leading to subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 162(11):2078–2085.

Poggesi, A., Pantoni, L., et al. (2011). 2001–2011: A decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) study: what have we learned about white matter changes and small-vessel disease? Cerebrovasc. Dis. 32(6):577–588.

Pohjasvaara, T., Mantyla, R., et al. (1999). Clinical and radiological determinants of prestroke cognitive decline in a stroke cohort. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 67(6):742–748.

Prabhakaran, S., Wright, C.B., et al. (2008). Prevalence and determinants of subclinical brain infarction: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology 70(6):425–430.

Qiu, C., Xu, W., et al. (2010). Vascular risk profiles for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in very old people: a population-based longitudinal study. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J. Alzheimers Dis. 20(1):293–300.

Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. (2001). [Clinical Trial Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Lancet 358(9287):1033–1041.

Ravaglia, G., Forti, P., et al. (2005). Incidence and etiology of dementia in a large elderly Italian population. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurology 64(9):1525–1530.

Reed, B.R., Mungas, D.M., et al. (2004). Clinical and neuropsychological features in autopsy-defined vascular dementia. Clin. Neuropsychol. 18(1):63–74.

Reitz, C., Tang, M.X., et al. (2010). A summary risk score for the prediction of Alzheimer disease in elderly persons. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Arch. Neurols. 67(7):835–841.

Roman, G.C., Erkinjuntti, T., et al. (2002). Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol. 1(7):426–436.

Roman, G.C., Tatemichi, T.K., et al. (1993). Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 43(2):250–260.

Ronnemaa, E., Zethelius, B., et al. (2011). Vascular risk factors and dementia: 40-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 31(6):460–466.

Sacco, R.L. (2007). The 2006 William Feinberg lecture: shifting the paradigm from stroke to global vascular risk estimation. [Lectures Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Stroke 38(6):1980–1987.

Sanossian, N., and Ovbiagele, B. (2009). Prevention and management of stroke in very elderly patients. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Lancet Neurol. 8(11):1031–1041.

Schmidt, R., Fazekas, F., et al. (1999). MRI white matter hyperintensities: three-year follow-up of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Neurology 53(1):132–139.

Schmidt, R., Ropele, S., et al. (2010). Diffusion-weighted imaging and cognition in the leukoariosis and disability in the elderly study. [Comparative Study Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Stroke 41(5):e402–e408.

Schneider, J.A., Aggarwal, N.T., et al. (2009). The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community versus clinic cohorts. J. Alzheimers Dis. 18(3):691–701.

Schneider, J.A., Arvanitakis, Z., et al. (2007). Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology 69(24):2197–2204.

Schneider, J.A., Wilson, R.S., et al. (2004). Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology 62(7):1148–1155.

Sheline, Y.I., Pieper, C.F., et al. (2010). Support for the vascular depression hypothesis in late-life depression: results of a 2-site, prospective, antidepressant treatment trial. [Comparative Study Controlled Clinical Trial Multicenter Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67(3):277–285.

Silbert, L.C., Dodge, H.H., et al. (2012). Trajectory of white matter hyperintensity burden preceding mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 79(8):741–747.

Silbert, L.C., Howieson, D.B., et al. (2009). Cognitive impairment risk: white matter hyperintensity progression matters. Neurology 73(2):120–125.

Skoog, I., Lithell, H., et al. (2005). Effect of baseline cognitive function and antihypertensive treatment on cognitive and cardiovascular outcomes: Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE). [Comparative Study Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Am. J. Hypertens. 18(8):1052–1059.

Smith, E.E., and Greenberg, S.M. (2009). Beta-amyloid, blood vessels, and brain function. Stroke 40(7):2601–2606.

Spence, J.D. (2010). Secondary stroke prevention. [Review]. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6(9):477–486.

Srikanth, V.K., Quinn, S.J., et al. (2006). Long-term cognitive transitions, rates of cognitive change, and predictors of incident dementia in a population-based first-ever stroke cohort. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Stroke 37(10):2479–2483.

Troncoso, J.C., Zonderman, A.B., et al. (2008). Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Ann. Neurol. 64(2):168–176.

Vermeer, S.E., Den Heijer, T., et al. (2003a). Incidence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 34(2):392–396.

Vermeer, S.E., Prins, N.D., et al. (2003b). Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N. Engl. J. Med. 348(13):1215–1222.

White, L., Petrovitch, H., et al. (2002). Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 977:9–23.