YOU KNOW THIS story:

A super-smart kid comes up with a big idea, quits college, and moves to the West Coast, where he sets up in a garage with a small team—“a hacker, a hustler, and a hipster” as Silicon Valley folklore holds it—to build a breakthrough innovation, then launches a company that disrupts an existing market and makes him and his team rich.

Here’s another version:

A super-smart employee, maybe no longer a kid, comes up with a great idea related to the company’s core business, but nobody in senior management wants to listen. So she quits the job and starts a new company on a shoestring, builds it into a huge success, and sells it to her former employer’s competitor.

The entrepreneurial narrative is innately, inevitably moving. It speaks to the power of human will, unifies public sentiment behind the ideas of a better world, fresh thinking, freedom, and self-realization—all while also promising wealth.

There’s just one problem with this particular narrative. It isn’t true.

The well-loved entrepreneurial story is more myth than reality, as entrepreneurial guru Michael Gerber points out in his enormously influential book and concept, E-Myth. The true story of innovation is less sexy, less sticky, and more complicated, which is why we don’t discuss it as often.

Here is what the true path of innovation looks like.

In late 1969, the same year the first human landed on the moon, Elliott Berman started thinking about the future—not just his future but everyone’s future, and not just the next year but thirty years ahead.

Much of the world was also worried about the future that year. Amid rising global inflation, political unrest, and ever-present racial, social, and economic tensions, energy dominated Berman’s thoughts. He believed that by the year 2000 the cost of electric power would reach the point at which we would need to look beyond fossil fuel. He became determined to help make alternative energy sources a reality.

Solar power was an obvious alternative, but at more than $100 per watt, it was far too costly. Berman decided he needed to find a way to bring down the cost. He was a scientist himself, but he knew he could not do it alone, so he assembled a team to research, experiment, and find a solution. They calculated that if they could somehow bring the price down to $20 per watt, they would open up a considerable market, which would lead to profits. They would also change the world.

Until that point, most solar cells had been used in space and so required expensive materials and wiring. On Earth, with different requirements, the team experimented with printed circuit boards. They found that they could glue circuit boards directly to the acrylic front layer of the solar cells with silicon. And instead of using silicon from a single crystal, the accepted rule at the time, they experimented using silicon from multiple crystals. Instead of using expensive, customized components, they looked for ways to use standard parts available from the electronics market.

Each innovation challenged the prevailing norms. None seemed particularly radical. But together, these changes enabled Berman’s team to bring the price of solar energy down fivefold, to $20 per watt.

1Innovation in hand, in April 1973 Berman founded a company, Solar Power Corporation (SPC), to commercialize the product he and his team had developed. They initially tried to sell their technology to the Japanese electronics conglomerate Sharp, but the two sides couldn’t agree on a price. So SPC decided to bring its innovation to market on its own. In its first year, SPC’s business development team convinced Tideland Signal to use SPC panels to power navigation buoys for the U.S. Coast Guard.

2Then they tried to convince Exxon to use their panels on oil-production platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. No thanks, Exxon executives said, we already have power. So Berman’s team flew to visit the people working on the platforms and found that the story on the ground was very different. Eventually they convinced Exxon to use SPC solar cells, and that led to solar cells’ becoming the standard power source for oil-production platforms around the world.

By bringing down the cost of solar cells so dramatically, founding SPC to commercialize his innovation, and passionately selling the innovation, Berman engineered a major leap in the evolution of the solar cell. Were it not for his entrepreneurial effort, solar-power technology might be ten years behind where it is today. Berman is admired as one of the most important pioneers of solar technology, with more than thirteen patents and innumerable research papers.

You could say that Elliott Berman was the Elon Musk of the 1970s. And yet you have probably never heard of him.

Why is this?

Because although his story is familiar in so many ways, one wrinkle makes it unusual. Berman was an employee of Exxon when he started his research, and the company he founded, SPC, was a wholly owned subsidiary of Exxon. Although few at the time knew the word, Berman was an

intrapreneur,

3 not an

entrepreneur. With a fierce belief in his idea, he significantly changed his slice of the world, and he did it without quitting his job.

The Truth About Innovation

Innovation and growth, as I’ve mentioned before, are the primary focus of my professional life. I realized early in my career that my mission is “people loving what they do.” I believe that having the freedom to innovate is a major contributor to loving your work. So, twenty years ago, when I felt I was not fulfilling this mission through my work at a global strategy consulting firm, I quit. If I was to be of service to organizations in their search for dynamic growth, and to individuals creating work they loved, I needed to understand as much as I could about how innovation really works.

But we should pause briefly here for a definition. The concept of innovation has been written about so often that there are many opinions about precisely what it entails. In this book, when I use the term “innovation,” I specifically mean something that meets these three criteria, on which a majority of definitions align:

1. Newness: A solution, idea, model, approach, technology, process, etc. that is considered significantly different from those of the past. We might say that for something to be an innovation, it must be surprising.

2. Adoption: Being surprising is not sufficient in itself. To become an innovation, a new idea must be adopted (or diffused).

3. Valuable: For something to be an innovation, it must be deemed valuable to relevant stakeholders (e.g., customers, investors, partners, and other stakeholders). Peter Drucker oriented his definition of innovation toward value when he wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth.

4

With that definition as a filter, I was ready to delve more deeply into the essence of innovation. I wanted to understand if Jean Feiwel’s story was an exception or the norm; I wanted to understand if, in order to innovate, employees needed to quit their jobs and become entrepreneurs, as is commonly believed and as I had done myself.

That search led me to a list of innovations that had most transformed our world in the recent past. A few years prior, the PBS business news program

Nightly Business Report had partnered with the Wharton Business School to answer the question “Which thirty innovations have changed life most dramatically during the past thirty years?”

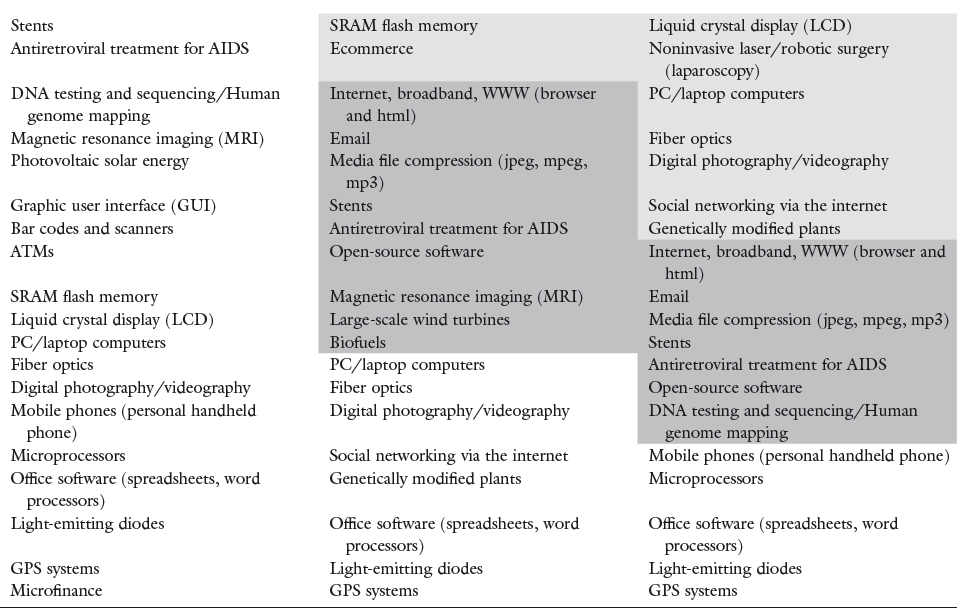

5 They asked the show’s viewers from more than 250 markets across the country, as well as readers of Wharton’s Knowledge@Wharton digital magazine from around the world, to suggest innovations they thought had shaped the world in the previous three decades. After receiving about 1,200 suggestions, a panel of eight experts from Wharton reviewed and selected the top thirty of these innovations. The list appears in the first column of

table 1.1; as you can see, it includes major innovations like the PC, the mobile phone, the internet, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

My research assistant and I then dug into the histories of these innovations. In particular, we tracked the three stages that are common to every journey:

1. Conception: Who conceived of the idea?

2. Development: Who developed the idea into something that works?

3. Commercialization: Who brought the idea to market?

TABLE 1.1

The Thirty Most Transformative Innovations of the Past Thirty Years

According to the hero narrative we like to retell, the answer to all three questions is the same: the entrepreneur conceives of the idea, develops the idea either on his/her own (Michael Dell in his dorm room building computers) or with a small team (Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in their garage), and then launches a company (Dell, Apple) to commercialize the idea. But let’s look at the facts.

Question: Who conceives of transformational ideas?

Answer: Employees.

Only eight of the thirty most transformative innovations were first conceived by entrepreneurs; twenty-two were conceived by employees. Without their inventiveness, we might not have a mobile phone to reach for in the morning, an internet to connect it to, or an email to send. If we got sick, we would not be able to get an MRI or have a stent implanted.

Question: Who develops the idea?

Answer: Corporate and institutional collaboration.

The second chapter of the entrepreneurial hero story has the entrepreneur working alone or with a small team to develop the idea. Actually, only seven of the thirty were developed this way. Most transformative innovations come to life when a larger community forms around the idea to develop it. In this stage, academia and institutions start to play a major role, particularly when the innovation has significant social value.

For example, in the midst of the 1973 oil crisis, a Danish carpenter named Christian Riisager grew interested in developing a large windmill that could generate enough power to be commercially viable. He designed one that could produce 22–55 kilowatts of power. After building and selling a few of these, he didn’t launch a company to further refine his design so it could be mass-produced. Instead, a community formed around his idea. This group, called the Tvind School, was formed by innovators and backed by other technology firms, including Vestas, Nordtank, Bonus, and later Siemens.

This pattern of community developing is common in medical innovation (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging, antiretroviral treatment for AIDS, and stents) but also in many other transformative innovations such as email, media file compression, and open-source software. Innovation more often comes from the collaboration of corporate and institutional employees than from small teams of mavericks.

Question: Who commercialized the idea?

Answer: Competitors.

As it turns out, only two of the thirty innovations were scaled by the original creators. And one of those innovations, microfinance, developed by Muhammad Yunus from my mother’s home country of Bangladesh, was scaled by the innovator himself only because he could not convince other organizations to copy him. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort.

Rather, more than 50 percent of the time (16 out of 30) the innovator loses control of the innovation. Competitors take over. Then, through a battle of players seeking to commercialize the innovation, the innovation scales.

Consider the Italian manufacturer Olivetti, which in the early 1960s was struggling to compete with large U.S. firms building massive mainframe computers. The company’s CEO, Roberto Olivetti, came up with a radical, seemingly impossible idea: to make a computer that was small enough to sit on a desktop.

He then handed the idea to a five-person design team, led by Pier Giorgio Perotto. The Olivetti team eventually achieved the impossible: a computer small enough to sit on a desk and economical enough to be acquired by an individual. The personal computer was born.

But management didn’t fully understand what their personal computer (called the Programma 101) was, and they didn’t appreciate its market potential. So for their display at the 1964 World’s Fair, Olivetti put a mechanical calculator front and center in its booth, and put the Programma 101 in a back room as an interesting oddity they were experimenting with.

But when an Olivetti representative showed the audience what the Programma 101 could do, they were stunned. This little device could perform intricate calculations—like the orbit of a planet—that until then had required mainframes that filled entire rooms. Market response was electric. Olivetti quickly started production. NASA bought at least ten to perform calculations for the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. The company sold 40,000 units at about $20,000 each in today’s dollars.

Olivetti had a hit that would transform the world.

Then the competition took notice. In 1968, HP launched its HP9100 series, which was later ruled to have copied several aspects of the Programma 101. That was soon followed by copycat products from innumerable competitors, including the Soviet Union MIR program, Commodore, Micral, IBM, and Wang.

New ventures don’t scale innovations; competitors do.

What I hope this quick analysis will show is that the entrepreneurial hero narrative is more myth than reality. We owe much of the modern world to the efforts and passions of internal innovators. To tell the true story of innovation, we would have to say that employees conceive of innovations, communities composed of corporations and institutions build them, and then the competition takes over to scale them.

The Double-Sided Advantage of Scale

Among the many advantages of innovation from within a company is the reciprocal relationship to scale. Being an innovator working from within an established organization can enable you to scale more quickly. And growing in scale makes more innovation possible. Let me tell you two stories to illustrate.

Heather Davis is a senior managing director at TIAA, a leading manager of retirement funds. The $45 billion private equity fund she helped build is one of the largest owners of wineries, farms, and other forms of agricultural real estate in the world. By investing in agricultural real estate and in technologies to increase farmer productivity, she is pursuing a mission to help prevent a world food crisis.

She has even used this platform to launch social efforts. When many of their farms were having trouble recruiting workers, Heather flew over to assess the situation. In a large apple orchard, she observed workers carrying heavy loads, performing repetitive tasks. Heather is also the mother of an autistic child, so it became immediately evident to her that such work was ideal for people with autism. She launched the Fruits of Employment program, which strategically employs workers with autism and other disabilities at agricultural sites such as apple orchards and vineyards. By doing this within TIAA, to the benefit of society

and TIAA, she was able to achieve instant scale, quickly reaching a level of impact that might have taken years to achieve on her own.

I’m sharing Heather’s story to illustrate the importance of scale. Startup companies are young, disruptive, and risk-taking. But once they find a business model that works, they start repeating that model in order to scale up. To do this, they turn to the bureaucracy they once scorned. They start narrowing tasks and tightly monitoring the performance of those tasks. They become risk-averse. Their level of innovation drops.

However, as they continue to grow, four factors come into play that invigorate internal innovators and give them great advantage:

1. They have scale that entrepreneurs cannot easily match.

2. They have access to multiple capabilities under one roof, tapping technology and experts from across the organization.

3. They can take advantage of resources their company has to invest (academics call these “slack resources”). Entrepreneurs must fundraise continually.

4. They can diversify risk. By making multiple bets, knowing some will fail but others will work, they can make the returns from innovation predictable.

One internal innovator explained it this way:

I could quit and start my own company, but if I do it here, I get immediate access to support, like legal and accounting. I get a brand that people recognize. When I make a phone call to a potential partner, I can get the meeting immediately. If I were a start-up, I’d have to make ten phone calls to get that meeting.

A few years ago I was visiting my mother at her home in Bangladesh and had the opportunity to meet Kamal Quadir. An MIT graduate and technology entrepreneur, he founded a mobile ecommerce business in Bangladesh called CellBazaar, quickly expanded it, and sold it to the Norwegian-based telecommunications company Telenor.

Kamal’s next big idea was to create a mobile P2P (person-to-person) payments solution. At the time (2010), mobile P2P was nearly unheard of by most U.S. consumers, though it was universal in Kenya and Nigeria, where more than 95 percent of adults used mobile phones to transact with each other. Kamal was ahead of his time.

If he set out on a typical entrepreneurial path, Kamal would get funding, code, then launch a company. Instead, he saw that he could scale much more quickly if he built the business from inside a larger organization. He brought the idea to BRAC, the largest nongovernmental organization in Bangladesh, which, among other things, operated one of the country’s largest banks. Within five years, he was able to reach fifteen million fishermen, small business owners, and others using his platform. As of this writing, his company, bKash, in which he retains partial ownership, has more than thirty-five million users.

Employees’ Ideas Often Matter More Than the Founders’ Ideas

Another assumption within the entrepreneurial myth is the notion that today’s successful enterprises spring entirely from the entrepreneur’s original business concept: Steve Jobs’s vision of a beautiful computer, Ingvar Kamprad’s vision of furniture sold in flat boxes, Jeff Bezos’s vision of an “everything store.”

In 1962, the physicist and historian Thomas Kuhn introduced a theory of “scientific revolution.” It posits that advances in science follow a pattern in which one revolutionary introduces a new paradigm and then other scientists follow to build out the details.

6 It’s often assumed that great companies follow a similar pattern.

But when we study what actually makes great companies great, we see that success depends more on the founder’s ability to create a system in which employees can bring ideas to reality. The ideas that turn organizations into market-shaping disruptors often come years after the original founder’s vision.

Gillis Lundgren, a young employee of a little-known mail-order furniture company called IKEA, was trying to deliver a table in 1953 when he discovered that it wouldn’t fit into the back of his small car. His solution: remove the legs. His boss, Ingvar Kamprad, immediately saw the value of this simple idea.

7IKEA at the time was a catalog business delivering furniture and other products mostly to homes in Agunnaryd, a small city in Sweden where Kamprad was born. Flat-pack packaging and self-assembly quickly became IKEA’s centerpiece business strategy. And you know the rest. As of 2015, IKEA had more than 150,000 employees running twenty-nine stores and distribution centers, with 800 million people shopping at the stores and 2.5 billion visiting the website. All this produced an annual revenue of more than $36 billion.

8Lundgren, who was IKEA’s fourth employee, worked for the company for more than sixty years. The former delivery driver was a talented designer, and Kamprad was wise enough to recognize it. Lundgren was eventually named head of design, where he played a major role in the company’s worldwide success. Altogether he designed more than two hundred IKEA products, and in 2012 he was awarded the Tenzing Prize, Sweden’s highest innovation award.

The IKEA story is compelling, but it is by no means unique. The pattern we see in most successful large organizations is the same. Growth comes not from the founder’s original idea but from his or her ability to activate the innovative prowess of employees.

Amazon does not generate significant value from selling stuff online, but rather from its services, from video to logistics to technology. Apple does not generate value from selling computers, but instead from iPhones, iPads, and other consumer services—ideas that were primarily advocated for by employees. The founder and CEO of Urban Outfitters, Dick Hayne, one of the fastest-growing and most profitable apparel retailers in the United States, told me that the innovations that propel its growth come from employees who bring in new ideas every day.

What About the Future?

I hope I’ve convinced you that our love affair with the “hero” lone entrepreneur and his/her role in our economic landscape is overstated. In point of fact, we now know that internal innovators have had a more significant effect on our lives than entrepreneurs.

Yet, when I lay out the facts at my workshops and speeches, I am often challenged by those who protest that my data are too old, that entrepreneurs are now taking the lead in innovation. The future, these skeptics claim, will once again belong to daring entrepreneurs.

Are they right?

I needed to dig deeper. So, with the valuable help of my research team, I analyzed recent data on innovation trends from respected sources such as

Forbes,

R&D magazine, and the Kauffman Foundation, the leading research institution dedicated to the study of entrepreneurship. Details of the research, including graphic presentations of the findings, are included in

appendix A. For the moment, I’ll summarize.

In a sense, the skepticism of those who insist the future belongs to entrepreneurs is understandable. For one thing, startup costs are coming down, thanks to access to cloud computing, 3-D printing, on-demand workers, and so forth. This should even the playing ground, making it easier for startups to compete with large incumbents.

Also, large companies are failing faster and earlier than before. A recent study of more than thirty thousand public companies over a fifty-year time span

9 shows that public companies today have a one-in-three chance of being delisted in five years (because of bankruptcy, M&A, liquidation, etc.). That is six times more likely than forty years ago. They are also dying younger. The average age of a company delisted in 1970 was fifty-five years. Today it is thirty-one.

More evidence: A famous study from Clayton Christensen’s consulting firm, Innosight, measured how long companies that made it onto the Standard & Poor’s 500 list stayed on the list. In 1960, they lasted about sixty years. Today, they last only about fifteen. And the Kauffman Foundation has shown that the length of time that Fortune 500 companies remain large enough to qualify for the list has been consistently dropping for the past five decades.

All of these facts fuel the idea that big companies are failing, leaving room for the small ones to take over. It’s a heartwarming David-and-Goliath story, but—and this is a big “but”—is it real? For this theory to hold up, we should see a parallel growth in entrepreneurship, with new startups popping up everywhere and pulling profits away from large companies.

It’s not happening.

The Kauffman Foundation found that the number of startups per 100,000 adults has been steadily declining. It started at more than 250 in 1997 and has been dropping steadily over the past two decades, though we saw an uptick in startups in 2016.

10If it were true that entrepreneurs are increasingly becoming the innovators, we would expect to see that the lists of highly innovative companies are headed by younger companies. That isn’t happening. Using the Forbes list of the most innovative companies from 2011 through 2017, we calculated how old each company was when it made the list. If younger companies are starting to replace older ones, the average age should come down. It doesn’t. We may think old companies like GE and J&J are being replaced by younger innovators like Tesla or Spotify, but the data don’t support that. If anything, the most innovative companies are getting older.

Then I wondered if “company” was the wrong unit of measure. After all, smaller entrepreneurial companies don’t yet have the scale to launch multiple innovations in any given year, so the “most innovative companies” list might skew toward larger organizations. I looked at the frequency of innovations, using R&D magazine’s annual list of one hundred top innovations from 2013 to 2017. If younger companies are starting to out-innovate incumbents, we should see the prevalence of innovations launched by younger companies increasing on the list. What we found, however, showed no such trend.

All this was running through my mind as I tried to formulate a response to the skeptics. And I came to the realization that when we set out to understand the full dynamic of innovation and think carefully about what lies ahead, the first thing we have to recognize is that the story is not one of big versus small companies, or startups versus veterans. Both struggle to endure. Something else is happening. What is driving the changes we are witnessing? A compelling answer is an acceleration in the pace of change.

Digitization and Acceleration

In 2017, electric-car manufacturer Tesla discovered a problem in their passenger-side airbag. They would need to issue a recall. In the same situation, most car companies would send letters out to drivers, ask them to bring their cars in to servicing stations, and have mechanics all over the country or the world make the adjustments. The process could take a year and cost tens or even hundreds of millions.

Tesla took a stunningly different route. It beamed down a software update that addressed the problem. The entire process cost a few thousand dollars of programming time (rather than millions) and took seconds (rather than months) to put in place.

We are starting to see similar stories, with similarly radical drops in cost and time, in nearly every sector: banking, retail, energy, consumer products, real estate, agriculture, fashion, hospitality, and more. Across the board, a sudden surge in speed and drop in the cost of delivering value are challenging incumbent organizations—large and small—to keep up.

Digitization Is Changing the Game…

You can fill an entire library with research, articles, and books on the transformational impact digitization is having. What first began with ecommerce is now restructuring entire industries. We used to buy a car because of its physical aspects (motor, wheels, chassis), and now a growing portion of the value we are paying for is software. We used to purchase typewriters (the keys, drum, case), but now pay mostly for word-processing software. We used to pay for physical books, but as of 2016 ebooks command 49 percent of the market. Everywhere we look, the physical is becoming digital.

Why does this matter? Ray Kurzweil, who, among other things, leads Google’s efforts in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and language processing, has shown that when artifacts become digital, then something he calls the Law of Accelerating Returns is activated.

11 The artifact’s performance per cost begins improving at an exponential rate. The implications of this are so profound that most organizations are struggling to deal with them.

The implications of the pending “digital revolution” are profound and well detailed in books like those of Kurzweil or

Exponential Organizations by Salim Ismail,

12 Kurtzweil’s colleague at Singularity University. To simplify, perhaps oversimplify, their thesis: a shift to digital is leading us into a world of exponential improvement in cost performance, accelerating the pace of change, and challenging and pushing hierarchical organizations to the limit as they increasingly struggle to keep pace.

…and Dramatically Lowering Costs

We see evidence of this exponential drop in costs across a variety of areas.

• In 2000, for example, the first human genome was sequenced. The effort cost $2.7 billion. Today improvements in computing and measurement have driven that cost down to less than $1,000.

• The toy drone that I—I mean Santa—gave my son for Christmas this year cost $20 on Amazon.com. Five years ago it would have cost $700.

• In 1977, one kilowatt of solar power cost $75; today it is 75 cents.

• A traditional artificial appendage costs $5,000–$50,000 to produce. Today, organizations like Po (

www.po.com.py) print them on 3-D printers for about $1,000.

Companies that embrace the digital, asset-light, idea-intensive revolution achieve radically lower cost bases and put themselves on the path of exponential cost improvement.

Why does this matter? Because it is driving their competitors into complexity.

Companies that fail to take advantage of the acceleration and lower costs that digitization brings face a terrible burden: they must increasingly compete with complexity. There are two reasons for this.

First, their competitors move more quickly. They adjust their product offering, pricing, distribution, and marketing messages weekly rather than annually. It is no longer practical to anticipate their big moves at the beginning of the year or to wait until the end of the year to decide how to react.

Second, there are simply more competitors. As the information component of products and services grows and the cost drops, the “barriers to entry,” as Michael Porter named them, fall. Organizations have to either adapt to a faster-moving, less predictable competitive environment or fall behind. Most organizations are struggling to evolve.

And here is the crux of the matter: to manage it all, organizations will need to reorganize. This puts internal innovators at the very center of the action, with unparalleled opportunities.

Hierarchy Cannot Keep Pace

Acceleration is thrusting traditional organizations rapidly toward a dilemma. Most of them are still primarily run as centrally planned economies. A central authority decides where capital and talent should be deployed; sets salaries; defines how much businesses should pay for internal support like IT, HR, or finance; and so on. When new information is received (“the average salary of database engineers is rising”), it is passed up the hierarchy through memos and meetings, and a decision is made (“let’s increase our salaries for database engineers by saving money somewhere else”) and then implemented (new salary bands are set, raises given, recruiting materials updated).

Gary Hamel has been studying the cost of bureaucracy for decades and concludes that while the world has changed dramatically, we continue to hold on to an outdated operating model—the bureaucracy—that companies will need to abandon if they are to survive.

We know how central planning worked out for economies. We are likely to see a similar bifurcation now with companies. Organizations that adapt their model, that abandon the centralized approach, will survive. Those too slow to adapt risk dying.

As we will see in

chapter 10, an answer is emerging. Forward-looking organizations are adopting a new, more agile organizing principle. They are evolving into platforms in which employees have the freedom to spot opportunities, act on them, and rally the resources to pursue them. In other words, we are entering a world that will thrust the internal innovator back into the central role of innovation.

A Final Word: The Financial and Human Problem

In summary, then, the data all point to the fact that internal innovators have been and continue to be critical drivers of innovation. We owe much of the modern world—from mobile phones to the internet, from MRIs to stents—to their creativity and persistence. Furthermore, all the evidence suggests they are playing an ever more critical role in shaping the future. We should be celebrating them, honoring them, and encouraging them. Yet too often we persist with the myth that entrepreneurs are the innovators that most matter.

This disconnect between the stories we like to tell and reality comes at a cost. One enormous cost is worker disengagement. More than 80 percent of employees in the United States and most other developed countries are disengaged at work,

13 meaning eight of ten workers spend their work hours just trying to get through the day.

This disengagement costs the U.S. economy about $450 billion per year in lost productivity.

14 That is more than the revenues of Amazon, Boeing, GE, and Google combined. It is more than all U.S. companies spend on R&D every year.

And that’s not all. Beyond economics, this is a major humanitarian problem. Disengagement at work has been shown to link to anxiety, depression, and damaged family relationships.

I believe that a major cause of this disengagement stems from the fact that most employees feel their creativity is being suppressed. Is it any wonder so many have lost their sense of purpose or passion? Imagine the growth we could fertilize if we could reignite that passion. Imagine what we could accomplish as a society if we could reinvigorate that sense of purpose.