CHAPTER THREE

THE ARCHAEOLOGIST IN THE FIELD

There is a cloud of noxious vapors which follows our group. It is a hybrid stench of destruction born from the ashes of microwaved blood, sweat, and DEET, sometimes a little marijuana smoke, and usually mostly sweat. This is the smell of archaeologists at work.

—Britt Arnesen (2001)

As I have shown in the previous chapter, entering the underground and accessing what lies below the surface can be rewarding in many ways. The aim of digging is to make discoveries and find treasures of various sorts, literally or metaphorically. Archaeology becomes an adventure into the unknown. It is these kinds of meanings of archaeological fieldwork and of making archaeological discoveries that I discuss in this chapter, thus continuing my discussion of the cultural connotations of archaeology.

The Adventure of Archaeological Fieldwork

Fieldwork has always been considered a crucial part of archaeology’s identity, both inside and outside the discipline (see DeBoer 1999). Among archaeologists themselves, those who do not do fieldwork are often mocked as “armchair archaeologists.” It is therefore not surprising that practical fieldwork is widely considered of central importance for the training of students. As Stephanie Moser (1995: 185) puts it in a study of Australian prehistoric archaeology, “it was in the field that students learnt how to ‘do archaeology’ and thus become ‘real’ archaeologiats.” This emphasis on fieldwork is, however, only partly to do with learning the practical skills of archaeology. In the field students also learn the unspoken rules, values, and traditions of the disciplinary culture of archaeology (Moser forthcoming; Holtorf forthcoming). Moser is therefore right in stating that going into the field can be considered the principal initiation rite for an apprentice archaeologist. Enduring the ordeals of fieldwork tests students’ commitment and, in turn, earns them rank and status. Such educational ideals and strategies probably go back much further than the origins of the academic discipline of archaeology in the age of modern nation-states, which have repeatedly gone to war against each other during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Military analogies implied in conducting “campaigns” of fieldwork, enduring tough conditions in the “trenches,” and enforcing “discipline” on site seem nevertheless to be particularly deeply felt among archaeologists (Lucas 2001a: 8). This is not surprising since a few influential, early archaeologists, such as Gen. Augustus Pitt-Rivers (1827—1900) and Brig. Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1890-1976) in the United Kingdom and Maj. John Powell (1834-1902) in the United States, had military backgrounds.

Archaeological fieldwork has traditionally had strong gendered associations and is often perceived as a masculinist practice. Based on her doctoral research in Australia, Moser (forthcoming) traces archaeology’s “masculine” associations back to the important roles played by themes such as the colonial frontier, romantic exploration, the outdoors, action, hardship, strength, and drink. Much of this imagery is taken up in one typical portrayal of the archaeologist in popular culture as a male wearing a khaki safari suit and a pith helmet, possibly carrying a gun (DeBoer 1999). Alfred Kidder (1949: XI) famously argues that

in popular belief, and unfortunately to some extent in fact, there are two sorts of archaeologists, the hairy-chested and the hairy-chinned. [The hairy-chested variety appears] as a strong-jawed young man in a tropical helmet, pistol on hip, hacking his way through the jungle in search of lost cities and buried treasure. His boots, always highly polished, reach to his knees, presumably for protection against black mambas and other sorts of deadly serpents. The only concession he makes to the difficulties and dangers of his calling is to have his shirt enough unbuttoned to reveal the manliness of his bosom. The hairy-chinned archaeologist ... is old. He is benevolently absent-minded. His only weapon is a magnifying glass, with which he scrutinizes inscriptions in forgotten languages. Usually his triumphant decipherment coincides, in the last chapter, with the daughter’s rescue from savages by the handsome young assistant.

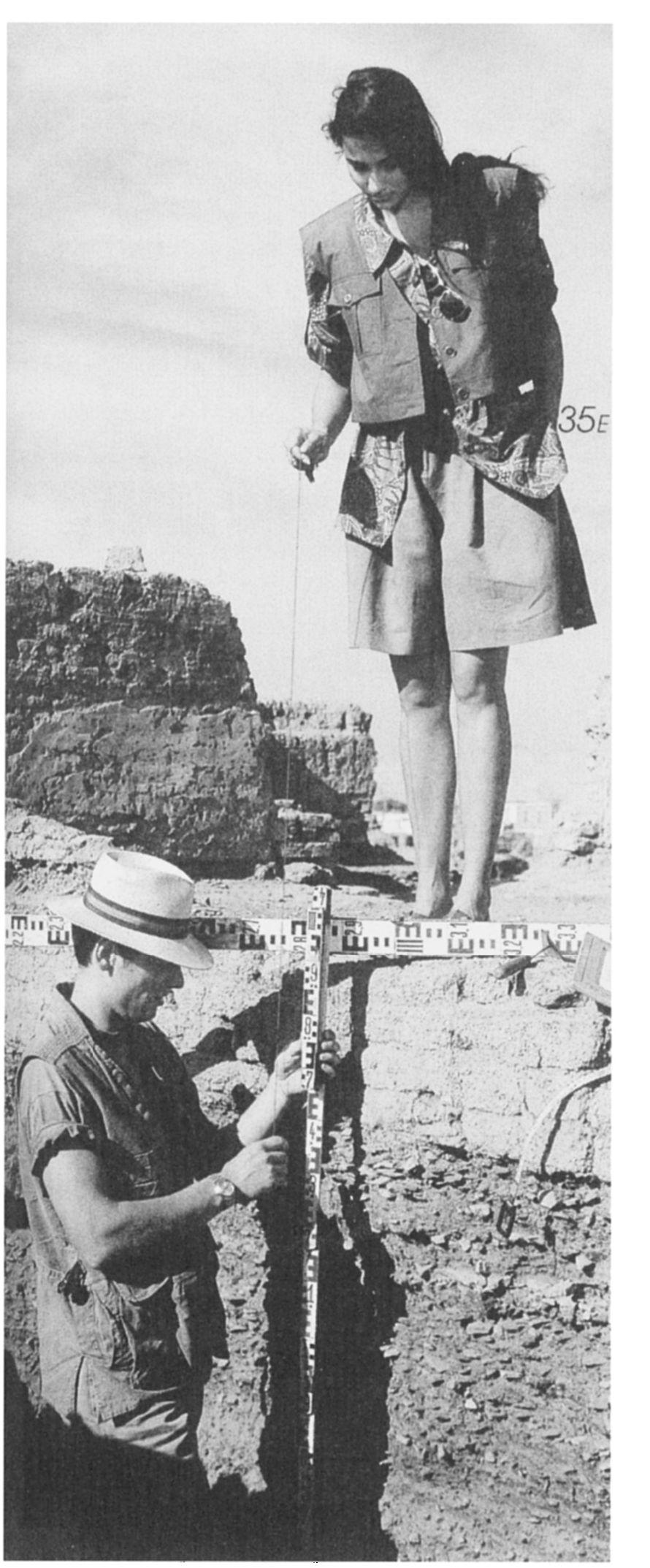

Figure 3.1 Fashion in the “colonial style” worn by “model archaeologists” at an excavation in Egypt. Source: Verena no. 5 (1990): 73. Photograph by Wilfried Beege, reproduced by permission.

With this cliché in mind, especially that concerning the hairy-chested archaeologist, the American archaeologist Larry Lahren once called archaeologists “the cowboys of science,” living a life of romance and risky adventure. In an article about Lahren himself, he was described as a horse-riding entrepreneur, once known for bar fights and unsuited to academic life but now working for the cause of archaeology (Cahill 1981). Another good example is the field archaeologist Phil Harding of the immensely popular British TV series Time Team (see www.channel4.com/history/timeteam). Stephanie Moser, a specialist in representations, describes him in her forthcoming essay as follows: “With his long hair, leather jacket, jeans, hat and strong regional accent, this fieldworker lives up to the popular conception of what it means to be an archaeologist. The cowboy type hat that he wears is of particular significance as a symbol of adventure and exploration.”

Arguably, this cliché archaeologist also has an impact on the self-perception of archaeologists, affecting recruitment, specialization, and preferences for certain professional activities. In the past women have sometimes been actively discouraged from going into the field at all. Although much has improved, and female students are now often in the majority in archaeology degree programs, they may occasionally still feel pressure (or a desire) to act more masculine on excavations. By the same token, supposedly feminine activities, such as drawing, can be frowned upon when carried out by male archaeologists (Woodall and Perricone 1981; Zarmati 1995: 46; Gero 1996; Lucas 2001a: 7-9; Moser forthcoming). Likewise, it might be argued that at least some of the fictitious female archaeologists appearing in popular culture, like Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft and Relic Hunter’s Sydney Fox (see table 3.1), are essentially male characters in female disguises.

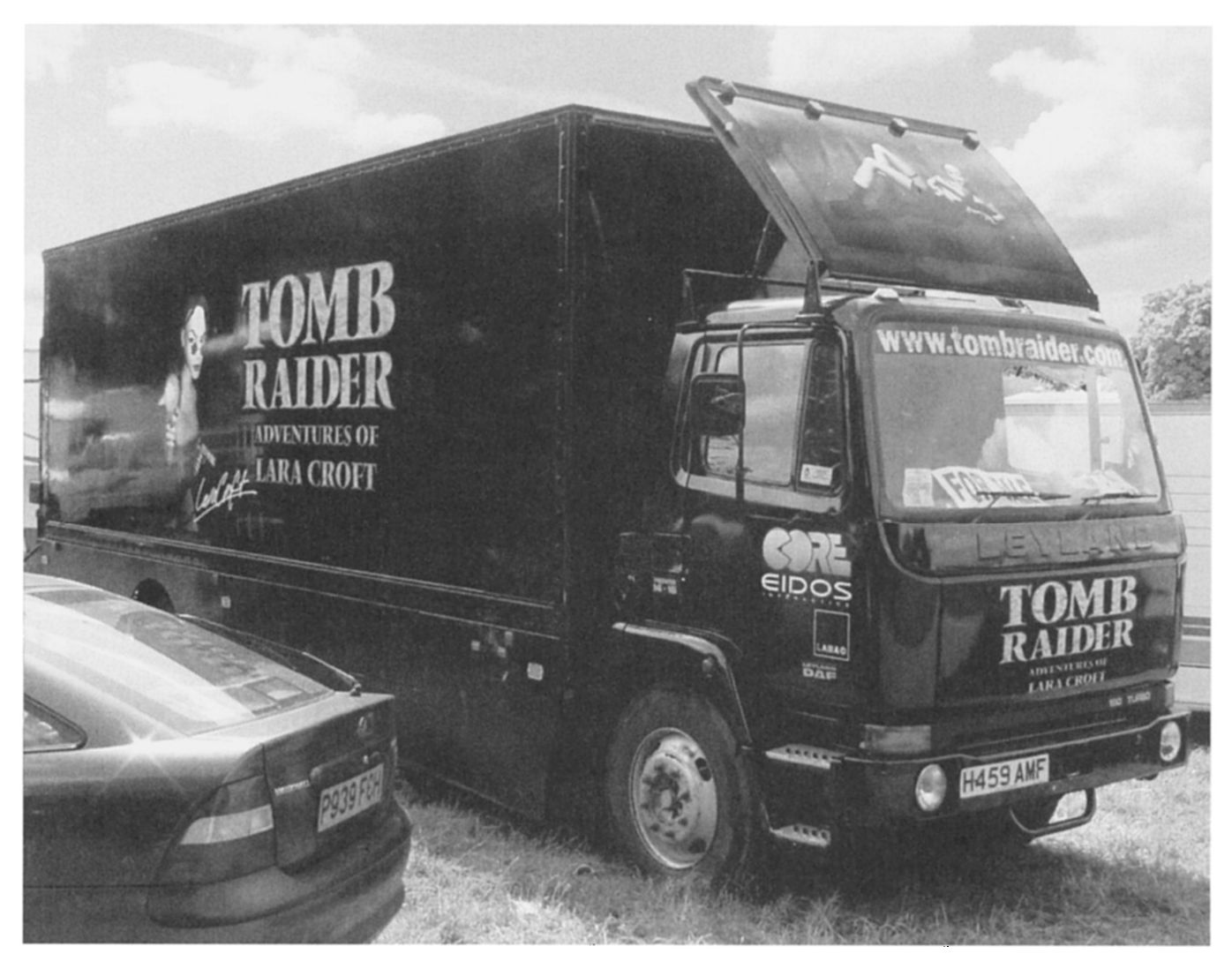

Although there are variations to the stereotype, the archaeologist remains clearly recognizable in popular culture, occurring widely in literature and the mass media, including film and TV (see, e.g., Membury 2002; M. Russell 2002). According to David Day’s survey of TV archaeology (1997: 3), there are almost 140 different films and videos that feature archaeologists. In recent years, the computer games of the Tomb Raider series (figure 3.2) have been particularly influential. Tomb Raider is the most popular archaeology-inspired interactive entertainment series released thus far. With total sales of the action games reaching twenty- five million units worldwide, each game has topped the PlayStation game best-seller lists. The subsequent feature film grossed more than U.S. $60 million from sales in its first week alone (Watrall 2002: 164). This astounding popularity implies that Lara Croft has an enormous influence on public perceptions of archaeology. The slightly older Indiana Jones movies of the 1980s have arguably been even more influential.

Table 3.1 Some Major Archaeologists of Popular Culture

| Archaeologist | URL | |

|---|---|---|

| Dr. Cornelius | A chimpanzee in the film The Planet of the Apes | www.movieprop.com/tvandmovie/PlanetoftheApes |

| Lara Croft | The heroine of the computer game and Tomb Raider films | www.tombraider.com; www.cubeit.com/ctimes |

| Professor Sydney Fox, historian in the Department of Ancient Studies | The heroine of the TV series Relic Hunter | www.relichunter.tk |

| Melina Havelock, marine archaeologist | Bond girl in For Your Eyes Only | www.thegoldengun.co.uk/fyeo/fyeowomendf.htm |

| Daniel Jackson, Egyptologist | The hero in the film Stargate and subsequent TV series Stargate SG-I | www.geocities.com/eventmovies/stargate.htm; www.stargatesgl.com |

| Professor Indiana Jones | The hero in novels by various authors and three films by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg | www.theindyexperience.com; www.indianajones.com |

| Indiana Pipps, Indiana Ding, Indiana Goof, Indiana Jöns, Arizona Goof, etc. | Goofy’s cousin who appears in Disney’s Donald Duck stories under various names in different countries | stp.ling.uu.se/~starback/dcml/chars/arizona.html |

| Professor Lucien Kastner, Sir Robert Eversley | Interviewees in the sketch “Archaeology Today” in Monty Python’s Flying Circus | www.ibras.dk/montypython/episode21.htm |

| Professor Kilroy, Professor Articus, Dr Charles Lightning | A character with different names in the Lego Adventurers theme featuring Johnny Thunder | www.geocities.com/EnchantedForest/Cottage/5900/Adventurers.html |

| Professor Fujitaka Kinomoto (Aiden Avalon) | Character in the originally Japanese anime Cardcaptor Sakura | sakura.prettysenshi.com |

| Dr. Eric Leidner | The murderer in Agatha Christie’s Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) | www.agathachristie.com/booksplays/bookpages/1961.shtml |

| Lintilla | A clone in Douglas Adam’s radio play The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy 2 (1980) | www.thelogbook.com/b5covers/hhg/year2.htm |

| Professor William Harper Littlejohn | A character in the 1930s/1940s Doc Savage novels by Lester Dent (and other associated comics, radio shows, and a movie from 1975) | members.aol.com/the86floormembers.netvalue.net/robsmalley; |

| Martin Mystère | The hero in an Italian comic series | www.bvzm.com |

| Evelyn O’Connell (Carnarvon), Jonathan Carvnarvon, Egyptologists | Major characters in the Mummy films and recent computer games | www.themummy.com |

| Amelia Peabody and Radcliff Emerson, Egyptologists | Main characters in a series of novels by Elizabeth Peters | www.mpmbooks.com/Amelia |

| Jean-Luc Picard, captain of the Enterprise; Professor Richard Galen; Vash; Lieutenant Maria Aster; Professor Robert Crater | Various characters in the TV series Star Trek and associated fiction | www.startrek.com |

| Will Rock | The hero of a computer game | www.will-rock.com |

| Professor Robson | The “hunky” professor in the soft-porn film series The Adventures of Justine (1995—1996) | rarevideos.bravepages.com/justine.htm |

| Professor Bernice Summerfield | The heroine of several novels by various authors, originally part of Doctor Who | www.bernicesummerfield.co.uk |

| Professor Hercules Taragon, Americanist | A character in two Tintin adventures | www.tintin.com |

| Miss Wood | A character in The King’s Dragon story of the children’s TV series Look and Read | www.lookandread.fsnet.co.uk/stories/king |

| All URLs were correct on October I, 2004. | ||

Featuring the archaeologist as a popular stereotype, the archaeological romance of eerie adventures involving exotic locations, treasure hunting, and fighting for a good cause has become a widely used theme in popular culture. Whether deliberately created as such or not, such stereotypes now occur in a wide range of popular-culture products and venues, including the following, among others:

Figure 3.2 Lara Croft in Cambridge, United Kingdom. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2002.

- Movies (Day 1997; M. Russell 2002; see also us.imdb.com/ search—search for “archaeologist” in “plots”)

- TV documentaries and series (Norman 1983; L. Russell 2002)

- Literary fiction (Korte 2000; e.g., Rollins 2000)

- Magazines (Ascher 1960; Gero and Root 1990)

- Advertisements (figure 3.1; Talalay forthcoming)

- Comics (Service 1998a)

- Computer games (figure 3.2; Watrall 2002)

- Toys (figure 3.3; M. Russell 2002: 51—52; e.g., Knight 1999)

- Theme parks and casino-hotels (see chapter 8; Malamud 2001)

The Hardships and Dangers of Fieldwork

Entering the underground is under any circumstances risky and dangerous. This holds true for miners and cavers as much as it does for volcanologists. You never know what is hiding in the darkness, and if you encounter something unpleasant or downright deadly, you cannot rely on making it back to the surface in time; you may even end up deeper still. The underground is full of unexpected surprises and unknown hazards, causing irrational fears. He who searches for treasures and brings light to where there was darkness must be willing to compromise safety and prepared to experience some pain. James Bond, for example, knows how dangerous it can be to enter the operation bases of his evil enemies, which are often, not coincidentally, located underground. These spaces contain both a lot of mighty weaponry and ruthless mercenaries who know how to use them. They also tend to contain some kind of superweapon, which threatens all humankind but requires both special expertise to be put to action and James Bond to be put out of action. The theme is old: in folklore mighty treasures are invariably protected by powerful superhuman security guards against whom we humans are mostly helpless. This is where risks and dangers meet their counterparts of control and protection. Both are two sides of the same coin. Subterranean military or political headquarters in deeply buried bunkers can so become spaces not only of great threat and danger for those outside but also of ultimate security and safety for those inside (see Williams 1990: chapter 7).

The archaeologist is generally the person who is, at least at first, not inside but outside such fortresses. Moreover, the archaeologist is frequently subjected to all sorts of threats to limb and life when attempting to get in. One great example for this image of archaeological fieldwork is James Rollins’s novel Excavation (2000), describing the discoveries and ordeals of a group of archaeology students in the Peruvian jungle. The text on the back cover reads as follows:

The South American jungle guards many secrets and a remarkable site nestled between two towering Andean peaks, hidden from human eyes for thousands of years. Dig deeper through layers of rock and mystery, through centuries of dark, forgotten legend. Into ancient catacombs where ingenious traps have been laid to ensnare the careless and unsuspecting; where earth-shattering discoveries—and wealth beyond imagining—could be the reward for those with the courage to face the terrible unknown. Something is waiting here where the perilous journey ends, in the cold, shrouded heart of a breathtaking necropolis; something created by Man, yet not humanly possible. Something wondrous. Something terrifying. (Rollins 2000)

Urban Explorers

Contemporary urban explorers are the archaeologists of the modern city. Although cities are human made, for those living in them it can still be exciting and adventurous to explore the seemingly uncharted areas below the city’s surfaces. These explorers are often well organized and publish detailed advice and reports about their explorations of abandoned factories, hotels, office buildings, tunnels, and drains, among other sites (e.g., Predator 1999; infiltration.org). One experienced explorer, who claims to “have done 147 drains in 6 Australian states, in addition to numerous rail tunnels, bridge rooms, abandoned bunkers and other concealed underground places,” explains the fascination of this hobby:

In life, you make choices. You can stay in bed and take no risks, or you can go out and get a life. This involves the taking of risks, telling of yarns, breaking of silly laws which restrict your freedom, finding out things of an unusual or interesting nature. Now, some people take drugs, some people watch TV, some people drive cars faster than the posted speed limit, some people get heavily into teletubbies, some people play golf. Since we find these things not very interesting, we explore drains. We like the dark, the wet, humid, earthy smell. We like the varying architecture. We like the solitude. We like the acoustics, the wildlife, the things we find, the places we come up, the comments on the walls, the maze-like quality; the sneaky, sly subversiveness of being under a heavily-guarded Naval Supply base or under the Justice and Police Museum.... We like the controlled nature of the risks involved. We like the timelessness of a century-old tunnel, the darkness yawning before us, saying “Come, you know not what I hide within me.” (Predator 1999)

A few years ago I participated in an international excavation project on Monte Polizzo on Sicily in southern Italy. I remember that one of the most exciting places to explore for many of the fifty plus project members was the deserted bottom floor of the building in whose first and second floors we were accommodated. This large space was once used as a clinic, and it had obviously not been cleaned up since its closure, only blocked off with bricks in a rudimentary fashion insufficient to stop us entering and exploring. We found a mess. One room was full of medical apparatus and papers spread out on the floor. In the center stood what looked like an X-ray machine; elsewhere were an old Italian flag, a plough that was possibly still being used occasionally and accessed through a locked gate, broken glass, and other rubbish spread out all around. One room full of sewage smelled appallingly. We loved it.

This will sound very familiar in the light of the previous chapter’s discussion. A secret and hidden site of the past can be reached by digging deeper; it promises earth-shattering discoveries and wealth beyond imagining, but the journey is, of course, also fraught with dangers.

Real excavations can be tough, too. The excavations on Monte Polizzo (Sicily) involved exhausting physical work on a mountaintop and a lot of sweating in the merciless Mediterranean summer sun. To compensate (and reward?) ourselves we drank all sorts of alcoholic drinks in the evenings and enjoyed visits to beautiful beaches on the weekends. An archaeological life of exhaustion and earned rewards (Holtorf forthcoming). Elsewhere, it is the cold climatic conditions that can make archaeology a tough occupation; for example in Alaska:

The advertisements for the Peace Corps say: “the toughest job you’ll ever love” but it’s clear to me that these people have never tried archaeological survey in the interior of Alaska. In the early morning we crossed a thicket of alders and everyone disappeared into the jungle. Only our voices could guide us through the rain. (Arnesen 2001)

Even when the geographical location and context is less exotic, as in urban archaeology, much tends to be made of those aspects of the project that retain at least some degree of adventure and earned rewards: the difficulties of interpreting a complex site, the bad weather, the mounting time pressure. Stories about the hardship of archaeological fieldwork and anecdotes about students or colleagues that derive from a shared experience of being in the field are generally a popular subject of conversation also among the archaeologists themselves. Sometimes in such discussions I recall some of my more extraordinary excavation experiences in 1991 and 1992 in Georgia.

Thesis 4:

Archaeological fieldwork is about making discoveries under tough conditions in exotic locations.

We flew to Tbilisi via Moscow, only two weeks after the attempted putsch and right in the middle of a civil war in Georgia. Our excavation site was far removed in the east of the country and fairly safe. But one weekend we arrived in the capital, Tbilisi, and could sense a strange atmosphere literally hanging over the town. That night, the town center had experienced violent clashes between supporters of the two sides. We saw people with arms, buses being used as roadblocks, and tanks moving outside the parliament building. Back on the excavation, some of our elderly workmen proposed toasts to the unforgotten Stalin. When we returned a year later for the second excavation season, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and a new government had taken over in Georgia. Bullet holes and burned-out floors marked the buildings of Tbilisi. During both years, we could sense how much our hosts’ attention was distracted from the archaeological site we excavated. But as guests we were told very little about what was really going on so that we had to rely on BBC World Service broadcasts to follow the events in our host country. Occasionally we Westerners were the honorary guests at local gatherings, but we never quite knew which of the political sides we served by lending them prestige and status in a bloody conflict. The day before we left, the local archaeologist we were staying with drove two of us through Tbilisi to visit a friend. After several checks at armed control posts, we reached a police station where the friend turned out to be one of the policemen on duty. Being a good host, he showed us the cells of his station, complete with their occupants. It became even more bizarre (and memorable) when we were offered live ammunition from his pistol as souvenirs since this was all he could offer under the circumstances. Contrary to my expectations, but relying on good local advice, I easily managed to smuggle my cartridge through the X-ray machine at the airport, and I have still got it.

Risks and dangers exist also on the metaphorical level. Casimir, the underground worker in Tobias Hill’s novel Underground (1999), for example, has got some reservations about the underground that turn out to be literal as well as metaphorical:

What disturbs him is what the Underground will do to people. It is where Casimir has come to ground, but he knows it can be an unsafe hiding place. Things are less mundane down here, more precarious. There is always the way the Underground can contain things, trapping them in its corners, hiding them, making them stronger. (p. 45)

Psychoanalytic treatment, too, may yield all sorts of frightening insights into a patient’s psyche and should therefore not be taken lightly. But for Freud even the adventurous aspects of archaeological fieldwork were part of his archaeological metaphor:

The narcissistic glory of Schliemann was meant to make the labor of remembering easier for the neurotic person. Everybody could secretly feel like a famous archaeologist. The strains of the excavation were comparable to the displeasure that set in when confronted with inhibitions to tell everything. If Heinrich Schliemann worked in the open in any weather, the patient too was not to shy away from every effort to dedicate him- or herself eagerly to Freud’s method of free association and thus to uncover his or her memory layer by layer. (Mertens and Haubl 1996: 18-19; my translation2)

Another kind of danger emanates not from what lies underground but from the explorers themselves. They can be responsible for various negative consequences, which the innocent, local people have to suffer as a result of their “lost” worlds being “explored,” their “mysterious” “treasures” “discovered,” and generally their “secrets” “revealed” (Cohodas 2003). Revealing secret truths undoes the status quo and causes change, not just in Western academia and for the explorers concerned but also at the sites of discovery. For example, internal conflicts may arise or additional outsiders may arrive and seek to exploit what archaeologists have revealed. In accounts of archaeological adventures, such consequences are often only retrospectively considered and regretted, when it is already too late. This more sinister side of archaeology, which in part draws on the uncompromising practices of some real explorers of the past, comes to the fore in archaeologists’ occasional portrayal as unscrupulous, colonialist treasure hunters who have initially no consideration for any of the upheaval they cause (see figure 3.3). In this vein, Miles Russell writes,

Archaeologists are the villains. They are tampering with forces that they do not understand. They are the people who raid the tomb, irrespective of the wishes and warnings of the local or indigenous population, awaken the dead, activate the curse, and bring down some immense supernatural nasty upon the world. (2002: 46)

The “curse of the mummy” is a good example of a legendary force of good protecting the legitimate interests of the people who buried the mummy for eternity. First popular after Howard Carter’s discovery of the grave of Tutankhamun in 1922 and the subsequent death of Lord Carnarvon, his colleague and sponsor, the curse has remained a key element of the image of archaeology in popular culture until the present day. Since the 1920s cursed Egyptian tombs have recurred frequently in all sorts of genres of literature as well as in many films and even blockbuster movies like The Mummy (see Frayling 1992; M. Russell 2002). If archaeologists can bring the past to life and reveal its secrets in the manner of saviors or magicians, there is always a risk, then, that the wrong forces will be unleashed. These are the powers they can no longer control, which threaten their survival and that of their associates, and which demonstrate the ultimate powerlessness of the archaeologists in the face of the mightiness of past civilizations.

Other dangers that may come from the archaeologists’ work relate to the way in which their work can be used in unstable political contexts (see Layton et al. 2001). An excavation site and its associated material culture may serve, whether intended by the archaeologists or not, as building blocks for modern nationalism and chauvinistic myths, usually by drawing on ancient glories or presumed long-term continuities (see Silberman 1995; Schmidt and Halle 1999). Ultimately such perceived historical foundations can even provide reasons and justification for wars. In the 1991 Gulf War, both sides used archaeology in their propaganda: whereas Saddam Hussein associated himself with ancient rulers like Sargon the Great, Hammurabi, and Nebuchadnezzar, the U.S.-led allies legitimized their efforts by claiming to protect “our common heritage” in “the cradle of civilization” from barbarians like Saddam (Pollock and Lutz 1994). A similar picture emerged once again during the war against Iraq in 2003.

Figure 3.3 Playmobil archaeologists in action: “Two explorers tiptoe softly through the jungle in search of the System X jungle ruin, passing exotic creatures like toucans, parrots, chimpanzees, and dangerous poisonous snakes. They are in search of the ancient mummy and legendary jewels hidden in the eyes of the ruin’s rock face. Through the thick underbrush—there it is! Quietly now, or the three native guards might hear. Others have tried to enter before, but a skull with armor at the foot of the stairs tells the story of how they failed. Our explorers manage to sneak by, just in time to reach the dungeon before the push-button gate closes. At last, the mummy! But where is the secret hiding place of the jewels? There’s no time to look now, they will have to return later. Good thing they have a map to find their way back through the dense trees, bushes, and hanging plants” (from wwwplaymobil.de, product description for pack no. 3015, accessed 26 May 2002). Image courtesy of Playmobil, a registered trademark of geobra Brandstätter GmbH & Co. KG, reproduced by permission. The company also holds all rights to the displayed toy figures.

Despite such dangers, people often feel compelled to reach below the surface or to observe others in their endeavors underground. Such quests for discovery are epitomized by the figure of the archaeologist doing fieldwork. Yet, archaeological discoveries are not merely appealing as the act of finding treasure below the surface, but also as a process of searching, encountering and categorizing. It is for this reason that archaeological discovery stories are often particularly exciting.

Archaeological Discovery Stories

The feeling of discovering something that bridges the seemingly unfathomable abyss between past and present continues to stir the popular imagination (Zintzen 1998: 138; cf. figure 1.3). It also reinforces the notion that seeking and making finds is a central component of archaeology, which contains “within itself that longing for the unforeseen, that passion for investigation and desire for discovery, which represent the basic motivation of true archaeological activity” (Pallottino 1968: 70). In all these stories, the inevitable climax is the moment of the great discovery, which comes unexpectedly and is in many instances made by complete outsiders. After the hardships of digging, finding treasure is the greatest moment of the archaeologist and a very emotional event. The most famous of these moments, which has often been staged in popular films, was Howard Carter’s opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Egyptian Valley of the Kings on November 26, 1922. In an often-cited passage, he describes the events as follows:

The day following (November 26th) was the day of days, the most wonderful that I have ever lived through, and certainly one whose like I can never hope to see again.... Slowly, desperately slowly it seemed to us as we watched, the remains of passage debris that encumbered the lower part of the doorway were removed, until at last we had the whole door clear before us. The decisive moment had arrived. With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner.... Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict. At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment—an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by-I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.” (cited in Frayling 1992: 104-105)

This is where the fascination of archaeology lies for many (cf. Ascher 1960). Agatha Christie, for example, who often accompanied her husband Max Mallowan on his excavations in the Near East (see Christie 1977; Trümpler 2001), found discovering artifacts irresistible indeed: “The lure of the past came up to grab me. To see a dagger slowly appearing, with its gold glint, through the sand was romantic. The carefulness of lifting pots and objects from the soil filled me with a longing to be an archaeologist myself.” (Christie 1977: 377)

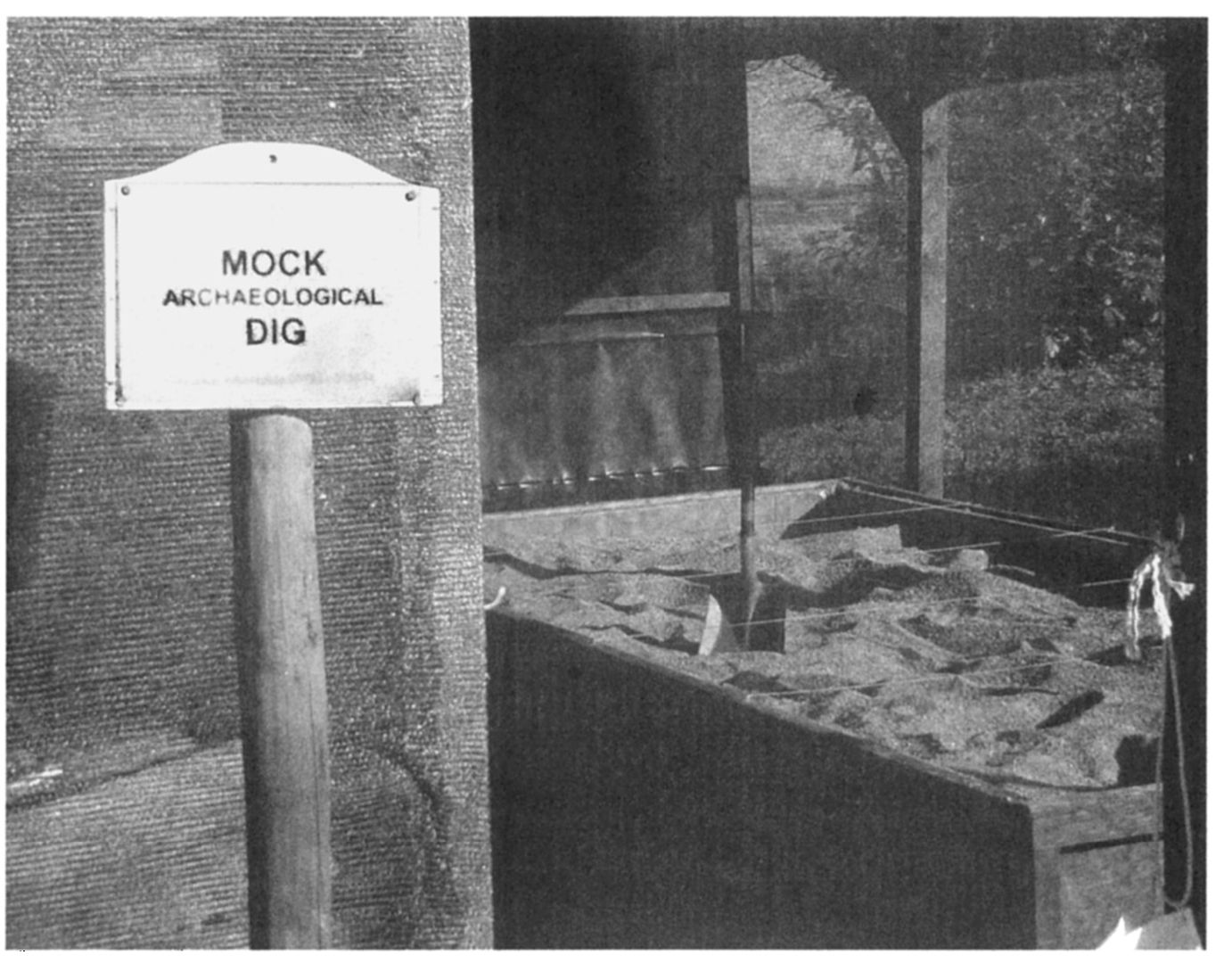

This sense of wonder is provided for children visiting Francis Pryor’s excavation site at Flag Fen in eastern England. The facilities include a sand pit where children are invited to dig for themselves and find their own (previously prepared) treasures that simulate archaeological finds (figure 3.4). I saw a similar attraction in a gift shop at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, with the main difference that the children were invited to buy the wonderful things they had discovered in the sand. All this resembles somewhat the staged excavations that have been organized since the eighteenth century for dignitaries visiting Pompeii: “A freshly discovered edifice which had been thoughtfully filled with coins or statuary was simply re-buried in order to be discovered once more, with well-rehearsed cries of surprise, in the honored guest’s presence.” (Leppmann 1966: 86)

This has been practiced in Germany, too. Reportedly, during the late nineteenth century, the German royal family and members of their household used to visit the Saalburg, a well-known excavation site of a Roman castle. On some of these occasions, finds made of chocolate were hidden in the ground. They dissolved quickly when the fortunate finder cleaned her discovery with water, much to the amusement of the onlookers (Löhlein 2003: 659).

Figure 3.4 Finding wonderful things. All is prepared for the Mock Archaeological Dig at Flag Fen near Peterborough, England. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2001.

Making archaeological discoveries is a literary theme that has also often been employed to tell the stories both of archaeologists’ lives and of the history of archaeology. In this perspective, the archaeologist is a passionate and totally devoted adventurer and explorer who conquers ancient sites and artifacts, thereby pushing forward the frontiers of our knowledge about the past. The associated narratives resemble those of the stereotypical hero who embarks on a quest to which he is fully devoted, is tested in the field, makes a spectacular discovery, and finally emerges as the virtuous man (or, exceptionally, woman) when the quest is fulfilled (see Zarmati 1995: 44; Cohodas 2003).

Best-selling accounts of archaeological romances involving mystery, adventure, and hardship and concluding with the reward of treasure were pioneered by the author Kurt W. Marek, alias C. W. Ceram, who published in 1949 his instant classic Götter, Gräber und Gelehrte (“Gods, Graves, and Scholars”). This book tells the story of the “great” archaeological discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, the Middle East, and Central America by focusing on the archaeologists themselves. Prominently included are accounts of the lives and archaeological accomplishments of Heinrich Schliemann (Troy and Mycenae), Arthur Evans (Knossos), Jean-FranÇois Champollion (Egyptian hieroglyphics), William Petrie (Egyptian pyramids), Howard Carter (Tutankhamun’s tomb), Henry Layard (Nimrud), Leonard Woolley (Ur), Hernando Cortés (Tenochtitlan), and Edward Thompson (Chichén Itzá), among others. The book has by now been translated into thirty languages (including English) and has sold almost five million copies worldwide (Oels 2002). The success of Ceram’s writing lies in a mixture of facts and exciting storytelling where readers suffer with their heroes until their eventual success. The use of numerous historical details and the frequent allusions to archaeology, continuously advancing our knowledge by deciphering more and more of the past, became key elements of a new literary genre thus established, the archäologischer Tatsachenroman, or fact-based archaeological fiction (Schörken 1995: 71-81). This genre was very successfully continued by others. The Danish archaeologist Geoffrey Bibby (1957) extended the chronological and geographical scope, reporting about prehistoric sites north of the Mediterranean. The German journalist Rudolf Pörtner popularized in several best-selling volumes archaeological discoveries and emerging insights into the prehistory and history of Germany (e.g., Pörtner 1959). Later, another German journalist, Philipp Vandenberg, successfully told (and retold) the stories and discoveries of archaeologists in Greece, Egypt, and the Middle East (e.g., Vandenberg 1977).

An often-used template for any such narrative has been the life and career of Heinrich Schliemann. Like few others, he personified the “lonely” hero who, despite being an outsider, knows “the truth”—in this case about the historical reality of Homer’s Troy—early on but is ridiculed until he finally embarks on his quest alone and under great difficulty. In the end, however, Schliemann and the archetypical hero prove themselves right by making great discoveries, becoming accepted as scholars, and being celebrated as national heroes. Many have since drawn inspiration and motivation from this truly mythical story in the history of science (see chapter 2). Even the German emperor Wilhelm II (1859—1941) was knowingly inspired by Heinrich Schliemann’s successes. Since 1911 he conducted regular excavations on the Greek island of Corfu and invited Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Schliemann’s former collaborator and successor in Troy, to join him not only during the excavations but also on his yacht cruises between the islands, using Homer’s Odyssey as his travel guide (Löhlein 2003). Wilhelm and countless other amateur researchers, following after Schliemann, exemplify the insight that heroes are not made by their deeds alone but mostly by the stories that are told about their achievements (Zarmati 1995: 44). They all have kept telling themselves heroic stories about archaeologists, while at the same time being keen to tell similar stories about themselves.

One aspect sometimes forgotten in these hero stories is their final element : the eventual downfall of the hero and his being cut down to size. Even the glory of Schliemann began to fade after his death, when questions were raised about the ownership of the artifacts he shipped out of their countries of origin and when it became clear to what extent he had fabricated even his own autobiography (see Zintzen 1998: 271-72). Likewise, Indiana Jones, in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, manages to get hold of the Holy Grail and save his father, but in the end he cannot hold on to it and remains an ordinary mortal.

The Act of Discovery in Archaeological Practice and Theory

But what about discoveries on modern excavations? How do they fit into the picture? In order to answer this, I first need to say a bit about the dominant understanding of archaeological finds and features as part of the “archaeological record” (Patrick 1985). This record has supposedly been formed by everything left behind from the past on a given site. All excavators need to do in the field is document this record, and for its interpretation the archaeologist simply needs to apply his or her expertise and competently read this documentation, thus the archaeological record itself. This scenario not only does an injustice to the creative tasks of recording and interpreting archaeological material, it also plays down the active role of the excavator in “making” a discovery in the first place, thus maintaining the illusion of an “objectivity” of archaeological facts (see Edgeworth 1990; 2003: 6). In much conventional science, the act of discovering data is indeed considered irrelevant compared to the act of its validation as part of a particular hypothesis. As far as archaeology is concerned, this view is naive (Lucas 2001b: 40).

The British field archaeologist Matthew Edgeworth suggested that to the same extent that theory and writing are kinds of archaeological practice, digging is also a kind of archaeological theory. He made the important observation that, for the most part, emerging objects are anticipated and, therefore, to a certain extent already known before they have actually been found. In this sense, archaeologists have perhaps only ever been able to find what they knew already and were thus able to see and to make sense of (Rehork 1987). Edgeworth found that excavators tend to describe the moment of discovery as the “popping out” or “leaping out” of the find from the soil being worked. They are instantly recognized due to socially shared cognitive schemes of what a particular kind of artifact looks like and where it might be found. For example, Edgeworth tells a story from an excavation of a Bronze Age cemetery on which one would normally expect to find arrowheads, but after six weeks still none had been found. Eventually, however, an arrowhead was found. When the excavator was asked what had first drawn her attention to it, she said, “There was something about the sheen of it ... it seemed to fall out of the earth nicely.” She had recognized it immediately as a worked flint and realized that it was an arrowhead when picking it up (Edgeworth 2003: 55). In cases such as this, the object not only suddenly emerges to catch the excavator’s attention and almost pulls her towards it, but at the same time the excavator’s anticipatory schemes also leap out to grasp or apprehend the object, both conceptually and physically (Edgeworth 1990: 246; 2003: chapter 7).

After Edgeworth’s work from the early 1990s, the act of archaeological discovery was not studied much until recently. The social anthropologist Thomas Yarrow (2003) conducted an ethnographic study of an archaeological excavation, looking in particular at the relationship between the subjectivities of the excavators and the objectivity of the site and its artifacts. He came to the conclusion that finds are “made” into objective “discoveries” by excavators acting objectively, i.e., in correspondence with the collective knowledge and the intellectual and bodily conventions of the discipline. Similarly, the archaeologist Gavin Lucas (2001b) proposed to consider archaeological fieldwork as a materializing practice. He argued that by digging up objects that become “discovered” finds or features, they are being materialized as something they had never been before: archaeological data. According to studies such as these, archaeology is not just disinterested observation, but an “encounter” with and transformation of material objects (see also Gero 1996; Lucas 2001a: 16-17; Pearson and Shanks 2001). Part of this encounter is the same sense of wonder that both fictional and nonfictional archaeologists cherish so much.

Figure 3.5 Archaeologist doing fieldwork. Use of this image permitted as a licensor of Corel. All rights reserved by Corel.

In both this and the previous chapters I have pointed to the cultural significance of two aspects of archaeology that are normally taken for granted and overlooked in many accounts of the discipline. The underground is a very rich cultural field, and every archaeological work that involves digging has to be seen in relation to it. Similarly, archaeological fieldwork is more than the sum of practicalities; it is an experience that is significant in several ways other than what it purports to be. It is also an adventure that is full of hardship but that eventually leads to wonderful discoveries. These dimensions belong to the materiality of archaeology itself.

But where does this leave the materiality of the past? What precisely is the archaeological value over and above the sense of wonder emanating from artifacts recovered underground by archaeologists in the field? For the most part, they are, of course, traces of past human activities. That brings me to my next chapter.