CHAPTER SIX

CONTEMPORANEOUS MEANINGS

People have been living in this town since the Stone Age. Proof for that is the seven meter tall Gollenstein which was erected here approximately four thousand years ago.

—Blieskastel, tourist leaflet (1993)

In this chapter I review what archaeological sites mean to people in the present. As I show in the previous chapter, prehistoric stone monuments can be very impressive and evocative features of contemporary landscapes and have for many centuries attracted a wide range of responses. They are also particularly well suited to serve as examples for studying the wide variety of meanings of archaeological sites today (see also the case studies in Gazin-Schwartz and Holtorf 1999). Prehistoric monuments are places to visit and to spend time; they are educational as well as mystical; their images appear in leaflets, on postcards, and in a variety of books. Archaeological sites are enjoyed by some, avoided by others, and kept in order by others again. Such contemporary meanings of the remains of the past, as they are exemplified in the various receptions of archaeological monuments in the present landscape, are the topic of this chapter: how people make archaeological monuments intelligible and how they make sense and use of them.

In short, this chapter is about Vorgeschichtskultur, or “culture of prehistory” (adapting Rüsen’s notion of Geschichtskultur, or “culture of history,” as discussed in chapter 1). Such an investigation requires a specifically ethnographic approach. I will therefore draw on extensive ethnographic research about three German sites, which I conducted during the early 1990s. My case studies were of two standing stones (menhirs) of the early Bronze Age, one the Gollenstein in Blieskastel, Saarland (figure 6.1) and the other in Tübingen- Weilheim, Baden-Württemberg (figures 6.2 and 7.1), and of one Neolithic long barrow containing several megalithic grave chambers in Waabs-Karlsminde, Schleswig-Holstein. During my research in the field, involving qualitative analyses of numerous documents, as well as questionnaires and interviews, I discerned fourteen different ways in which these sites are meaningful today. Just as the previous chapter includes a long-term account of the changing meanings of two categories of finds and sites, I draw here on a small sample of sites in order to illustrate the contemporary variety of meanings. The existing overlap between the various meanings demonstrates the many interdependencies between the categories discussed (see also Holtorf 2000-2004: 5.0).

Figure 6.1 The Gollenstein in Blieskastel, Saarland, Germany: sit down properly, enjoy, and learn. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 1995.

Monumentality

Monumentality was what mattered most about the monuments to the first antiquarians. That is why they called these monuments “megaliths” (“large stones”) or “menhirs” (“long stones”). Indeed, even today many people experience megalithic monuments mostly in terms of their sheer size and the huge weight of the stones used. At the Gollenstein, I asked a boy who was perhaps eight years old what he thought of the stone. He replied that he liked it “because it is so tall!” By the same token, the Gollenstein in fact is the largest menhir in central Europe and used to be mentioned as such in the Guinness Book of World Records. The information board at the long barrow of Karlsminde states that the monument is an amazing 60 meters long, 5.5 meters wide, and includes 108 stones weighing between 1.5 and 2.5 tons. Members of the group of volunteers who reconstructed the long barrow from 1976 to 1978 remember vividly how they had to cope with these truly monumental stones: “In the end we were so fit ... our record was to erect eight stones on one day.”

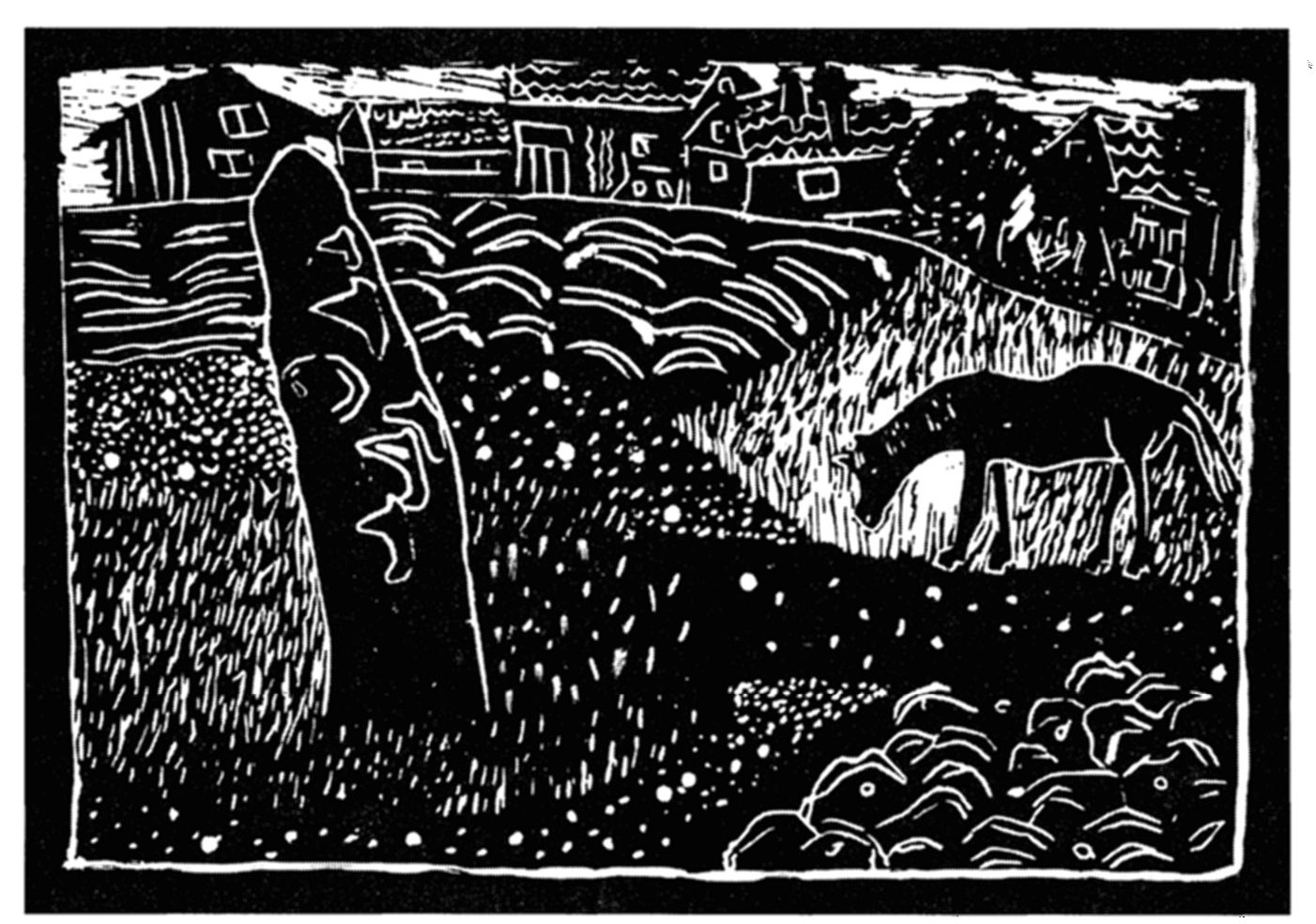

Figure 6.2 The menhir of Tübingen-Weilheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Wood engraving by Friederike von Redwitz, Weilheim (1991), reproduced by permission.

The outstanding visibility and dominant position of the large stones in the landscape is also what attracts people to go and look at megaliths. At Karlsminde, strollers, cyclists, or families traveling by car often spot the monument from a distance and then approach the site to have a look at it. Most visitors then walk around the monument once, read the information board provided, take a picture, and after three to five minutes, leave again. Local people, who are familiar with the site, also tend to head for specific places when out walking, and the long barrow is one such destination. The same goes for menhirs, which are particularly attractive also to dogs, which frequently leave their markings there when passing by on walks. Hence, a neighbor referred to the menhir in Weilheim as a Pin-kelstein (“peeing stone”). Monuments can be targets also in another sense. The Gollenstein stood exactly on the German Westwall, the Siegfried Line. Being taller than 6.5 meters, it could easily have been used by hostile artillery as a point of orientation, thus illustrating once more the potential for monuments to change their meanings dramatically (see chapter 5). At the beginning of World War II, the menhir was therefore pushed over and as a result broke into four pieces. It was reerected in 1951. Today, amateur airplane pilots still employ clearly recognizable features in the landscape, like menhirs and megaliths, to orient themselves.

Factual Details

Professional archaeologists especially tend to consider prehistoric monuments as remains inherently containing scientific information about processes and events that took place in the past. Often, they emphasize such factual details: what it is, who discovered it, how large it is, how old it is, if there are any comparable finds elsewhere, and so on. A lot of people think that knowledge about an archaeological site necessarily appears in the form of such detailed information and scientific facts. Although considered boring by many, such facts are invariably also mentioned during guided tours, on leaflets and information boards, in documentary reports in the media, and in lessons taught about the monuments in schools. An astonishing number of visitors seem fully satisfied with the site after having subjected themselves to reading such details. Some can never get enough information about whatever little detail, as some quotes from my questionnaires and interviews illustrate: “I am interested in everything”; “I want to know everything which I don’t know already”; “there are thousands of questions which make one suffer, somehow.” Indeed, amateur archaeologists are sometimes able to provide their professional counterparts with new details and information about known sites or even to find new ones.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, archaeologists are often perceived as knowing the factual details best and, thus, as the most important scholarly experts concerning ancient sites. Indeed, some were confused when I asked them about the meaning of a monument. Even regarding their own perspectives, they seemingly preferred to rely on experts: “Since you study this, you should know the answers!” Amateur archaeologists sometimes try to convince their professional colleagues of the quality of their own work by imitating even the dry and unimaginative writing style found in so many academic works offering scientific expertise. Similarly, in order to impress me with their knowledge, some of my interviewees had obviously made an effort to memorize some supposedly basic facts (dates, measurements, technical terms). Factual details thus acquire metaphorical significance and are used to display conformity with perceived educational values and to express desired social distinctions (see Schulze 1993: 142-50).

Commerce

Archaeology and prehistoric monuments as a part of the archaeological heritage have proven both popular and commercially exploitable (cf. Kristiansen 1993). Some sites, although not those among my case studies, charge entrance fees. Business people can also make profits selling archaeological merchandise, such as postcards showing the local monuments like those for sale at the camping ground in Karlsminde and throughout the town of Blieskastel. Furthermore, the Gollenstein features on tiles, beer mugs, drinking glasses, egg cups, and so forth. A large oil company once offered to sponsor a rose tree at the Gollenstein in order to boost its regional image. In a similar effort, the local bank of Blieskastel distributed bottle openers in the shape of the Gollenstein.

Monuments are also important as factors stimulating the economy of the area in which they are situated (cf. Liebers 1986: chapter 11; Schörken 1995: chapter 4.2). In the mid-1970s the economic situation in Waabs was such that it required an additional attraction for tourists. The former mayor explained the situation to me:

What do we have to offer here? We make guests come here and advertise with brochures. We advertise with the Baltic Sea, with the beach, and with our landscape. But not only those people come here who lie on the beach from morning to evening. They also want to get to know the countryside and the people. And what can they visit here? The church of Waabs used to be all we had. Now [the reconstructed long barrow of] Karlsminde has been added. (My translation3)

Bus tours to Karlsminde now even come from Denmark. Investing money in the preservation and restoration of archaeological monuments thus attracts heritage tourism and brings money into the local community. Not surprisingly, images of prehistoric monuments appear widely in tourist advertising material and in travel guides.

Social Order

The various receptions of monuments are in many ways mirrors of the present. Interpretations of megaliths are often linked to contemporary assumptions, associations, and analogies and are subject to changing social policies and fashions. References to common stereotypes make sites popular and economically successful (see chapter 8). Our own social order is perhaps most visible and enforced at occasions like opening ceremonies such as those that took place at the restored Gollenstein in Blieskastel in 1951, at the reconstructed long barrow in Karlsminde in 1978, and at the new replica of the menhir in Weilheim in 1989. These rituals usually consist of a performance by a musical band, followed by several speeches given by political dignitaries and representatives of appropriate archaeological institutions, eventually leading to an extensive informal party with food and drinks provided. In Karlsminde even Gerhard Stoltenberg, then prime minister of the state of Schleswig-Holstein and a leading member of the Christian Democrat Party at the national level, came to open the megalithic tomb to the public.

Another example of the extent to which contemporary social norms and values dominate the meaning of monuments is provided by what is considered their proper reception. The geographer Tim Cresswell (1996: chapter 4) demonstrated how the conflicts over recent decades at Stone-henge were ultimately based on different social values held by the conservative government under Margaret Thatcher and the free festivalers and their supporters (see chapter 5). Whereas the government portrayed itself as the protector of moderate middle-class citizens against lawless hippies, some festivalers in turn saw themselves as the better people, who cared for preservation, nature, and spirituality.

According to the values of the educated middle classes, which governments and their agencies tend to make their own, archaeological sites have to be in order, i.e., they have to conform to certain expectations. The grass around the monument should be cut. A bench is where visitors are supposed to sit and enjoy. Bins are provided for any waste, and they have to be emptied regularly: no decay must be visible in any form. The information board is written by the experts and lets you know what you need to know. The visitor’s interpretation of the monument has to be in order as well: what differs from standard interpretations runs the danger of being mocked and dismissed in public as Schnickschnack (“twaddle”). If you conform to expectations, you display your high-level education and culture.

There are also orders of research. Archaeologists study the past according to the rules and norms of academic discourse (cf. Shanks 1990; Tilley 1990). Often they have to comply not only with unwritten laws about the ownership of particular bodies of material in order to gain the cooperation of their colleagues but also with strict rules of how archaeological material has to be analyzed and interpreted in order for their manuscripts to be accepted in particular academic journals or book series. Sometimes amateurs are not taken seriously by professional archaeologists for the reason that they do not have academic titles in front of their names or an institution behind them. Significantly, the then state archaeologist of Schleswig-Holstein stated in a letter to me that “asking a state archaeologist what a megalithic tomb means to him is like asking the pope what the Catholic Church means to him.” In this view, the state archaeologist is defined by his relation to the monuments and considered as being firmly in control of them, while possibly being infallible in matters of belief and judgment. Alternative claims to archaeological monuments are effectively treated as heresy. How we interpret and deal with monuments and with the past in general depends, then, greatly on their metaphorical significance and has to a considerable extent to do with social power.

Monument preservation, too, is part of our social order. Insofar as it follows from specific laws, it can even be enforced by the police. At the worst, heavy fines or even jail sentences may result from serious offences against such laws. People have thus become cautious about alarming the authorities. A resident of Weilheim had noticed the large menhir on the building site where it was found for several weeks but preferred not to report it. She said, “Well, I thought, it’s better not to interfere, it’s not your business. Don’t cause a stir, they might start digging and who knows what else.” She described what happened when archaeologists eventually discovered the menhir after being tipped off by somebody else: “the two [pre-historians] went straight to the mayor and confiscated the stone, as it were. This impressed me somehow: a stone which lay there unnoticed for months, and now suddenly it was important, at this moment on the record, officially protected.”

Remembrance

Monuments, as memorials, also remind (mostly) local people of events that have taken place in that area many years before. Inhabitants of Blieskastel associate the Gollenstein with the time when they were children : “I spent my childhood in its vicinity”; “I grew up with it as a child and I have known it forever”; “as children we went up there to play.” Some elderly people remembered World War II when I asked them for the meaning of the menhir: they still think of the Siegfried line running there. An ex-soldier had especially vivid memories of the monument:

When we as soldiers were on leave home and the train approached Blieskastel, we could see the Gollenstein first. Later, when it lay broken, it was a dreadful feeling: the symbol of Blieskastel! And when I returned from captivity I had to fall in line up there and help to put things back in order. (My translation4)

The restoration and reconstruction campaign at Karlsminde in the late 1970s, as well as the opening ceremonies of all three monuments, stayed in people’s minds for a long time too. In Karlsminde, locals recall the fact that the prime minister of Schleswig-Holstein attended; in Weilheim a couple remembered that “it was a very turbulent festival” back in 1989. Prehistoric monuments also remind some visitors of other archaeological sites they have seen abroad while on holidays. People from elsewhere, in turn, remember their stays in Karlsminde, Weilheim, or Blieskastel when they look at their photographs showing the local prehistoric monument. In addition, some visitors leave visible traces behind at monuments, such as graffiti, in order to remind others and themselves of their visit. By carving their initials and the year (or whatever else) into the stone, they hope to render the monument into a memorial of their visit and of themselves, hence gaining “nominal immortality” (Lowenthal 1985: 331).

Thesis 8:

Archaeological sites mean very different things to different people, and these meanings are equally important.

Identities

A relation to the past is crucial to people’s identities (Lowenthal 1985: 41-46). Prehistoric monuments in particular can serve as powerful emotional foci for both personal and collective identities and thus become a metaphor for yet another thing.

For example, a megalith might be considered to represent somebody’s personal identity. The woman who first recognized the menhir of Weilheim considers this stone as her own life’s work; she is convinced that if she dies the menhir may be what remains of her life. This may also be the reason others feel inspired to carve their initials in monuments such as the Gollenstein. For the amateur archaeologists who took part in the restoration and reconstruction of the long barrow of Karlsminde, the monument became an important part of their life histories and identities, too; one of them called it even “my baby.” In Blieskastel, one amateur archaeologist set up a miniature park of menhirs and dolmens in his back garden, and the same man sells hand-carved wooden Gollensteins for little money at local flea markets. Somebody else feels so close to the same menhir that he calls the stone “my friend.” A couple of years ago an artist planned an installation involving the Gollenstein in order to “get into the stone and to melt together my innermost part with it.” This project has never been carried out though. Amateur researchers may spend years of their lives and large proportions of their savings on trips to archaeological sites around the globe in order to write new accounts of the past. But professional archaeologists, too, see ancient monuments sometimes as much more than objects of study; they feel and care for them, and they even like spending their holidays and retirement age in their occasional company. Archaeological work can thus become very personal indeed (cf. Shanks 1992: 130-31).

Collective identities can also be connected with archaeological monuments. People have always identified themselves with the place or area in which they are living, and they are generally proud of its heritage, often eager to show “their” antiquities to visitors. Another factor has now been added. The faster the world we live in changes, with people feeling increasingly alienated from the actual bases of their lives, the more we may come to draw on the past as heritage for a compensating reassurance about who we actually are (cf. Nora 1989). Ancient sites can become symbols of common roots and a communal spirit that binds a community together (see Schörken 1995: 111-12, 127). This community may be the village where the monument is situated, the nearest town, a district, a region, a state, or an entire nation.

Even a monument that has only recently been dug up is rapidly considered to be part of “our past.” In Weilheim people are proud that their own village with a menhir from the early Bronze Age is ostensibly older than the neighboring Kilchberg, which has “only” a reconstructed burial mound of the Iron Age. Inhabitants of Alschbach, which today is part of the town of Blieskastel, jokingly still claim the Gollenstein as theirs because it stands on what used to be their land. Even so, the town of Blieskastel now happily advertises with the phrase “attractive for 4,000 years” (see also the quotation at the beginning of this chapter). There is also a lot of local pride about having “Germany’s tallest menhir” in the small town of Blieskastel. In the summer the entire town celebrates the annual Gollensteinfest. Posters of the Gollenstein can be found in many local shop windows, and one person admitted to me that she also has a poster of it hanging above her own bed. The menhir is also used as a name for a local travel agency, Gollenstein-Reisen.

Moving on from the local to the regional level, it is significant that in his six-page speech script for the opening ceremony in Karlsminde, the prime minister of Schleswig-Holstein managed to include the name of his state no less than fifteen times, the word for “state” was used another fifteen times, and eleven references were made to Heimat (which refers to a very strong sense of belonging to a community and its traditions). Thereby, Prime Minister Stoltenberg reassured people about where they belong at the same time that he linked himself, the government, and his party with the regional identity of the area. By the same token, in the Saarland all children in their final year of primary school (at the age of 10) take a trip around their state. The Gollenstein has traditionally been a part of the itinerary because it is seen as a monument of key significance to the children’s Heimat. To refer publicly, when at prehistoric monuments in Germany, to a common national past is rare and widely considered as a form of unapproved nationalism (see Schmidt and Halle 1999), but the equivalent is common in other states such as Denmark (see Kristiansen 1993). In one instance I encountered a notion of universal human identity: a woman considered the menhir of Weilheim as part of the “history of mankind.”

Ancient sites can also come to stand for various social identities. Perhaps most visible to archaeologists is the meaning they acquire for them themselves. The long barrow of Karlsminde, for example, is often presented to visiting archaeologists or conference participants as some kind of shop sign or showpiece for local archaeology. Unsurprisingly, the group of volunteers who originally restored the site had also developed a strong bond to the site that effectively defined their relationship to each other. Monuments can be important foci for nonarchaeologists too, as the various documented communities interested in Stonehenge illustrate (see Chippindale et al. 1990; Cresswell 1996: chapter 4). Among my case studies, the Gollenstein, for example, is known as a place where local youths meet occasionally for nocturnal parties, seemingly deriding the venerable monument.

Aesthetics

A lot of people come to see megaliths because they enjoy the scenery and the aesthetics of prehistoric monuments. Ancient ruins partly decayed and grown over have long inspired the Western imagination (figure 4.3; see also Lowenthal 1985: chapter 4; Woodward 2001). It is therefore not surprising that ancient sites in the landscape often feature prominently in tourist brochures, as mentioned before.

Ancient monuments evoke a particular form of romanticism, and they are often especially appreciated at sundown. For example, a neighbor of the menhir in Weilheim stated, “Sometimes it is so lovely when we experience sunsets here—I can well imagine that they practiced a cult of the sun here at certain times.” In many cases, such impressions are intensified by the monument’s remoteness and the tranquility and beauty of the surrounding landscape. A brochure about Eckernförde, from which Karlsminde is within convenient driving distance, observes that “the charm of the rural atmosphere is impressed by millennia and preserved in its origin.” Both amateur and professional photographers regularly visit monuments in order to take pictures capturing this atmosphere. School parties draw them in class after joint visits. Even oil paintings of archaeological sites in the landscape are occasionally produced, continuing a genre that was first made popular by romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich.

Reflections

A monument’s age encourages people to reflect upon themselves and the world in philosophical terms. It seems as if the presence of a witness from the past can quite easily evoke profound existential reflections, for instance about the course of time, death, and decay, and the hopes and values by which we live today. Deep thoughts I came across include the following:

When I see this stone I know that I stand on ground that is historically eminent, where already in 2000 BC a lot happened. To me, [the monument] is the visualization of a spirit which is transmitted through the generations.

The Gollenstein is a venerable witness of the past.... In its stony tranquillity ... the Gollenstein is a reminder for us of the transitoriness of all human doings as well as of the insignificance of the daily arguing about trifles.

Sometimes I get the impression that many contemporaries, in terms of religion, beliefs, etc., live very superficially. I think that perhaps such an old stone may also encourage certain reflections: why did they build it? Then I have secretly the very tiny hope that people may also ask themselves: Well, what do I stick to in my own life? (My translations5)

Adventures

People visit archaeological sites in their leisure time, seeking special experiences that can, for instance, be gained by visiting exotic curiosities and strange wonders. That is precisely what many prehistoric monuments offer: they are very huge, very old, and very extraordinary. As metaphors for the strange, they stimulate people to feel extraordinary, too (see Köck 1990; cf. Schulze 1993). This inspiration is one aspect of what I will call the “archaeo-appeal” of ancient sites and artifacts (see chapter 9).

There are two main kinds of adventurous archaeology signified by archaeological monuments. One is the encounter with an exciting and adventurous past. Such a past is often depicted in images of (pre-)historic life but has ultimately more to do with certain needs and desires of the present. American archaeologist J. M. Fritz (1973: 75-76) writes about the appeal of the prehistory of Arizona to the “common man”:

The vicarious but safe experience of the drama implicit or explicit from archaeological accounts of the invasions; the movements of people; the burning and looting of towns; the revolutionary transformations; the interplay of priests, rulers, and warrior castes; or simply the day-to-day exertions of living and of “man the hunter” are undoubtedly related to deeply felt needs.... For such men [and women] and perhaps for us, the past is an empty stage to be filled with actors and actions dictated by our needs and desires. For individuals, the past provides escape ... and opportunity to produce good and evil and to create and thus control events we most desire or fear. In this sense, the past is an extension of dreams and daydreams.

Donald Duck has been known, too, to long for “adventure—the kind of rip-snorting fun those old Vikings must have had!” Consequently, he embarked on precisely one such adventure, chasing the golden helmet (see Service 1998a).

These kinds of connotations of the past may also be the reason why certain feasts and ceremonies are held at some ancient sites nowadays. In Blieskastel, the annual summer Gollensteinfest has proven extremely popular since it was first established in 1971. On that particular weekend, almost the entire town gathers around the Gollenstein, and people enjoy themselves while eating, drinking, and dancing to live music. Occasionally, smaller and more private feasts are held at the Gollenstein as well: I was told about a Beltane festival, an American Indian fancy-dress party, an end-of-excavation party, and a party of acolytes of local parishes, as well as several Whitsuntide scout jamborees and numerous feasts of local clubs and groups of youths with campfires and freely flowing alcohol.

Whereas archaeological monuments like menhirs and megaliths may once have been positioned in places that were (or became) special and different from those normally frequented, nowadays they derive much of their special appeal from the different time period they are associated with. Many people, including children, love speculating about what went on at such monuments during prehistory. In popular books and media productions, as well as in the opinions of some of my interviewees, prehistoric monuments are interpreted as astronomic observatories, as places of ancestor or sun worship, magic ritual, fertility cults, human sacrifice, and cannibalism, as well as seats of chiefs, princes, or kings, and so on. It seems that the stranger, the better (cf. Schmidt and Halle 1999). In a similar spirit, the megaliths of Schleswig-Holstein are also known as the pyramids of the North. Likewise, menhirs are not infrequently associated with the comic figure Obelix, who supposedly as a small child fell into a pot of magic potion brewed by the local druid, giving him superhuman strength and the ability constantly to carry a menhir on his back. Extraordinary goings on at monuments are also told of in legends and fables that still surround many prehistoric sites (see Grinsell 1976; Liebers 1986).

People enjoy reliving the excitements of the past. Few things, for instance, are as popular as prehistoric flint-knapping demonstrations. When (pre-)historic events are reenacted, everyday life is relived, or ancient technologies are tested by experiment, these extraordinary and exciting activities as such appear to attract people (cf. Schörken 1995: 134-37; Gustafsson 2002). One recent study (Hjemdahl 2002: 111) showed that even peeling carrots can be experienced as fun as long as you are “in the past”!

Sometimes, reliving (pre-)history can enable the unfulfilled wishes and desires of the present to become true by projecting them onto the past. The Swedish archaeologist Bodil Petersson (2003: 339-46) demonstrated how reconstructions and reenactments of different periods have appeals for people with different lifestyles and desires. The Stone Age offers a happy, egalitarian, and ecological idyll involving all sorts of simple technical skills; the Bronze Age is more hierarchical and adds cosmology, ritual, and cult issues, which suit those inspired by New Age ideas; families with children are attracted to daily life in the Iron Age, characterized by farming and breeding livestock; the Viking age is often male oriented, involving heroes on ships, traders in markets, and visitors to festivals; the Middle Ages, finally, have even more markets and festivals, especially tournaments, and are full of knights, merchants, and nobility, with everybody playing very clearly defined roles.

A second kind of adventurous archaeology is the idea of archaeology as an adventurous endeavor in itself. In this view, archaeologists are handsome adventurers who lead dangerous lives on the trail of treasure in foreign countries (see chapter 3). Some sort of special excitement about archaeology was certainly required by the volunteers who worked in their leisure time over several years at the reconstruction of the long barrow of Karlsminde.

Aura

Prehistoric monuments are authentic witnesses of bygone times (see chapter 7). They emanate aura and cosmic atmosphere. A visitor to Karlsminde thus enjoyed the site of the reconstructed long barrow for it allowed him “to let his soul swing.” One man I met in Blieskastel claimed to be able to “see the aura” of the restored Gollenstein and enjoyed being there at night or during the early hours of the morning. Its aura was ostensibly unaffected after the site had been restored and renovated. Indeed, restoring, reconstructing, or maintaining an ancient monument is often the result of a particularly deeply felt admiration, respect, and even reverence for the past and its remains. At the opening ceremony of the long barrow at Waabs-Karlsminde, the local mayor declared in this vein, “We bow down in great respect before those who constructed this monument.” Moving any such site away from its current position might thus destroy the aura of the monument.

When I asked the head of the municipal cultural authority in Blieskastel why he would not want to put a copy in the place of the Gollenstein, which is jeopardized by environmental pollution, he replied, “Somehow, it wouldn’t be the same.... This wouldn’t be an appropriate thing to do.” This concern was borne out when the original menhir of Weilheim was moved to the museum in the state capital, Stuttgart, and replaced by a replica (see chapter 7). In addition, not long after the replica was inaugurated in 1989, a fire hydrant and several brightly painted posts were placed right in front of the menhir. Not much of an aura or much sense of authenticity is now perceptible there. Every visitor instantly discovers the replica at the very latest when knocking against it: “It sounds like a plastic watering can,” one local said. People thus experience the menhir as “made of plastic” and a “fake.” In a local publication Ute Jöns-son expressed a more widely felt desire in asking rhetorically, “Who does not want to touch at least once the original daggers [which adorn the menhir] with his or her own hand?”

Magical Places

A lot of people are attracted by a somewhat magical mystery that surrounds ancient monuments. Some see menhirs in general as places of magical practices performed by fertility cults and as phallic symbols. Interestingly enough, some elderly inhabitants of Blieskastel remember well that the Gollenstein also used to be the target of various Easter processions from the surrounding villages. At the beginning of the last century, a little niche was cut into the monument and may have been filled with a saint’s figurine. Perhaps this was an effort to Christianize the site physically as well. Even today, quite a few pilgrims who come to Blieskastel as a place of Roman Catholic pilgrimage visit the Gollenstein afterwards. As a matter of fact, it is very difficult to get people talking about anything that could be considered superstitious or occult because the public discourse in our society tends to disapprove of any such affinities. Usually only evidence for lovers’ rendezvous at monuments is found or given, but even this may be significant. An elderly woman, after I had asked her for her associations with the Gollenstein, said, “Well, what do we think there? We ought not to reveal it at all. Once in May, we were young—then we often went up there.”

During the night of the summer solstice in 1993, a couple of teenagers appeared at the Gollenstein and put a candle in a small niche of the menhir. I asked one of them why they came there on that day, and I was given the following information: “I knew, in Stonehenge etc., there is always something going on [during this night]. I expected that there would be some people here. And, of course, I have been joking all the time that you get sacrifices of virgins here on that day” (My translation6).

Such jokes certainly refer to, and further popularize, interpretations of monuments as places where magical practices once took place and sacrifices were offered to the gods. Although there is thus some affinity in the present with the magic of monuments, it is not always entirely serious. A local vicar said that he would think that “the people are pagan in other ways than that.” The local police station in Blieskastel could not provide any evidence for pagan rituals at the Gollenstein either. But another person I met had an idea to celebrate pagan weddings at the Gollenstein. He considered such rituals at that place as an appropriate alternative to what the dominant, Christian church is performing nowadays. One reason for this may be that prehistoric monuments are occasionally seen as places where sacred forces of nature can be experienced (see Chippindale et al. 1990: chapter 2; Shanks 1992: 59-63; Schmidt and Halle 1999).

There are special techniques that allow some of us to sense the force fields of the earth, which are related to its magnetic and electrical fields. They usually employ various kinds of rods. According to these somewhat esoteric approaches, monuments were built at locations where such fields are strongest, often along the ridges of hills. There is a connection here to the famous ley-lines, i.e., alignments of ancient sites stretching across the landscape, because such forces are believed to be responsible for the human organization of the landscape in general, resulting in sacred geometries. Often, monuments are sites where some can sense such underlying powers of nature, known as “Earth mysteries.” As one person I spoke to put it, it is possible at such locations “to fill up with energy.” The same man spends a lot of time at the Gollenstein “opening [himself] to Truth and endless Love.” It is sometimes assumed that the druids were especially capable of experiences such as this and developed around them a secret knowledge of nature. In some people’s views, we should aim at regaining such insights in order to understand better not only the ancient monuments but also the world in which we are living now.

Nostalgia

Following a nostalgic view of the past, some find the past, for instance the Neolithic, more attractive to live in than the present because “in yesterday we find what we miss today” (Lowenthal 1985: 49). People of the past were allegedly more open to the spiritual and to cosmic vibrations in the landscape: they were less strongly rooted in the material. About the Gollenstein I was told, “The past humans lived in an even and stable context. All tensions and contradictions were ultimately reconciled.” A resident of Weilheim stated that in the past “all was of one piece. Everybody knew what to do and what to believe. The world was like this and that was it.” Somebody else said, “humans then also did not take themselves as so important.” For others again, prehistoric people lived in harmony with their fellow humans and with nature: “People then were more reasonable” than we are today, as someone put it in conversation. In this view, we should try to reach this state again in order to save the human race and indeed the entire world from evil. Supposedly, people in the past also lived idyllically, “less hectically,” and in harmony with nature because “everything was nature then.” At the same time, people were not at all primitive but “as intelligent as we are”: “they had all the ancient monuments after all.”

Many difficult problems we are confronted with today did not exist several millennia ago: there was no pollution of the environment, no danger of another world war, and no traffic either. A schoolgirl wrote on one of my questionnaires, “Given all that you hear now in the news—I would rather have been on earth during a former age!” Life used to be just nice; simply “everything was better.” An archaeologist told me that he, too, wished he had lived in an earlier age

because then the ways of warfare, for instance, were much more humane really, if you think about it. Today you can be as strong and clever as you want—in a war you would be lost.... In former times strength, aptitude, and reason were still in the foreground. They are after all essential virtues of human beings. (My translation7)

Progress

According to the opposite view of the past, the past was primitive and not worthy of reliving, whereas our future in fact depends on continuous progress. The human beings who built the monuments are considered to have been backward and poorly developed culturally because they did not yet have many of the later inventions of modern civilizations. They used hand axes and wore furs, “hunted foxes and rabbits in the forest,” and lived in caves without any heating, except their campfires. Life must have been difficult: “they did not have an Aldi [supermarket] then, and they had to make sure they would survive the winter.” One schoolgirl stated, “The humans were poorer in former times and I do not approve of that.” They also did not have doctors or dentists. Life was therefore continuously put at risk by disease and, what is worse, by slavery. A woman in Blieskastel admitted to me that if she had lived in the past she would have been constantly afraid of being burnt as a witch.

Progress is supposedly obvious in the history of archaeology, too. Educational curricula and the media tend to make much of the continuous progress of the sciences, and archaeology is seen as one of them. Most scientific archaeologists are indeed explicitly working towards this aim. The history of the discipline has been written as a story of continually improving our knowledge about the past, although other views are equally possible (see Schnapp 1996). This may explain why so many people rely happily on the expertise of archaeologists as scientific specialists. It could be argued, however, that this notion is self-serving since it secures the archaeologists’ social status and justifies their claim to intellectual control over the past.

Ideologies

Certain qualities ascribed to the past or to monuments are ideological in the sense that they legitimize particular social and political claims or interests (see also Tilley 1989a). By signifying the distant human past, archaeological sites have an important metaphorical potential, which may become ideological when supposedly reflecting how best to act and think “naturally.” Changing explanations for past events and processes can reveal in retrospect how every generation of scholars had its own explanatory factors that offered themselves naturally, giving answers that were plausible at the time because they related to dominant ideologies and common ways of interpreting the world (see Wilk 1985). Both nostalgia and progress can have strong ideological dimensions in that they seem to point to a better way of life that will, however, suit some contemporary needs better than others.

All these various meanings are given to the prehistoric monuments I investigated, signifying various aspects and dimension of contemporary knowledge about the past and its material remains. They illustrate how ancient sites can function as metaphors for a wide range of meanings and values. These results of my fieldwork, although no more than a first attempt to come to terms with the contemporary meanings of prehistoric monuments, raise some important questions. If interpretations and meanings of archaeological objects vary to the extent shown, depending on the particular viewpoint and interest of the observer in each present, where does that leave the very materiality and the authenticity of genuine artifacts ? Can the aura of the original remain unaffected when everything else is in motion?