CHAPTER NINE

ARCHAEO-APPEAL

If it is the crime of popular culture that it has taken our dreams and packaged them and sold them back to us, it is also the achievement of popular culture that it has brought us more and more varied dreams than we could otherwise ever have known.

—Richard Maltby (1989: 14)

I started this book by stating that archaeology is a fascinating theme of our age and then claimed that it was significant to the world in which we live. In the previous chapters I have reviewed some key aspects of archaeology and archaeological practice and occasionally pointed to reasons for the popularity of both archaeology and its subject matter: the past and its remains. But one overriding question remains to be dealt with in more detail: what is it that makes archaeology so extraordinary and appealing in our society? In this chapter, I propose that the answer lies in the special “archaeo-appeal,” doubly manifested in doing archaeology and in imagining life in the past. In other words, the popular appeal of archaeological methodology, sites, and artifacts is less due to some subtle characteristics of the source material or the subject matter and relies more on broader aesthetic experiences and metaphors.

Why Zoos Are Fun

A general trend away from valuing “pure” objects and towards broader experiences is typical of many themed environments, among them, contemporary zoos. Looking at zoos can provide a number of important insights that have relevance also to archaeology.

Besides their serious roles in preservation and education, modern zoos are very much about family entertainment, and it is this aspect especially that accounts for their enormous popularity. People visit zoos not to learn about animals, but to have a good time and talk to each other about the animals. Scott Montgomery (1995: 575) states correctly that “if the zoo were about learning, in any institutional sense, no one would go.”

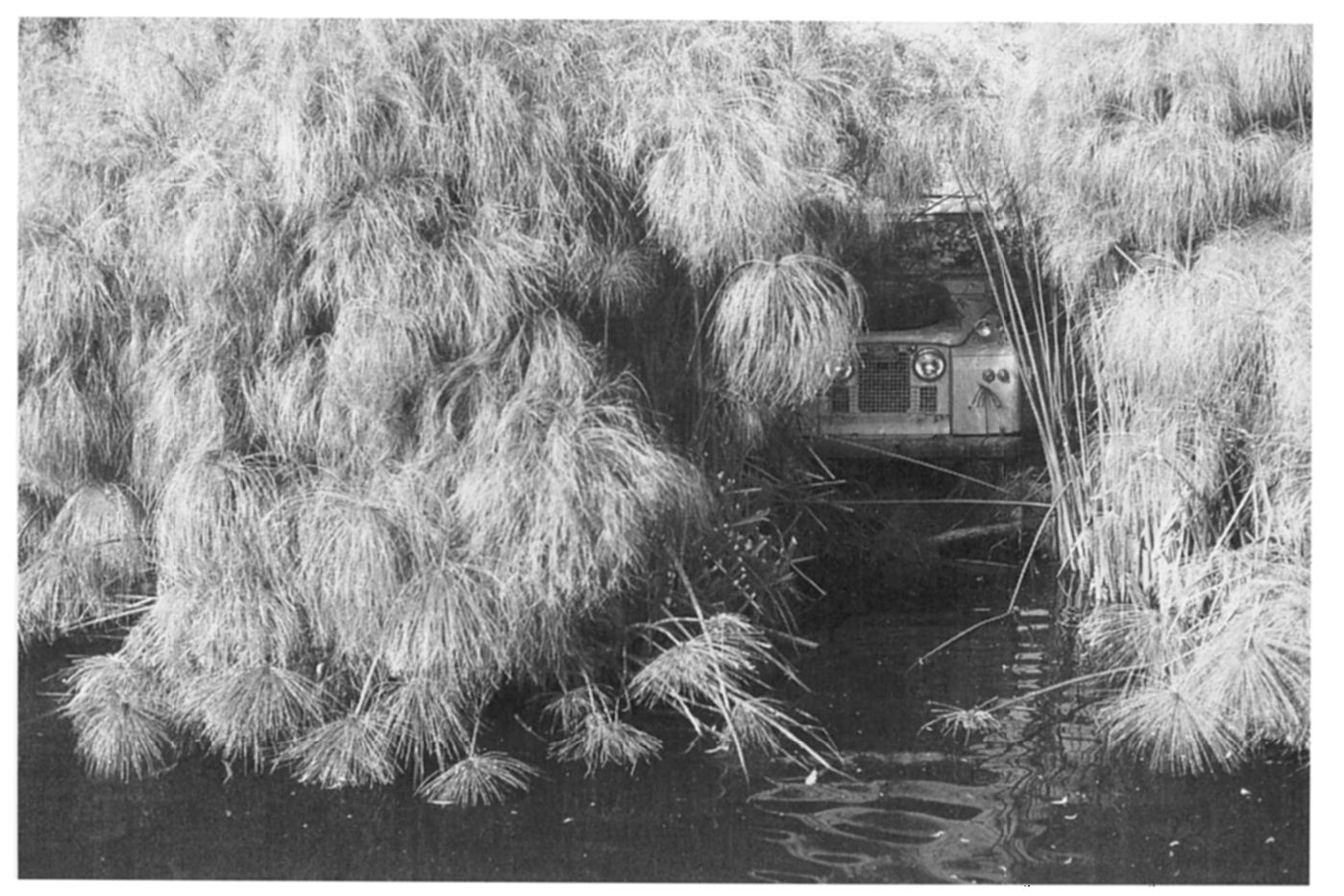

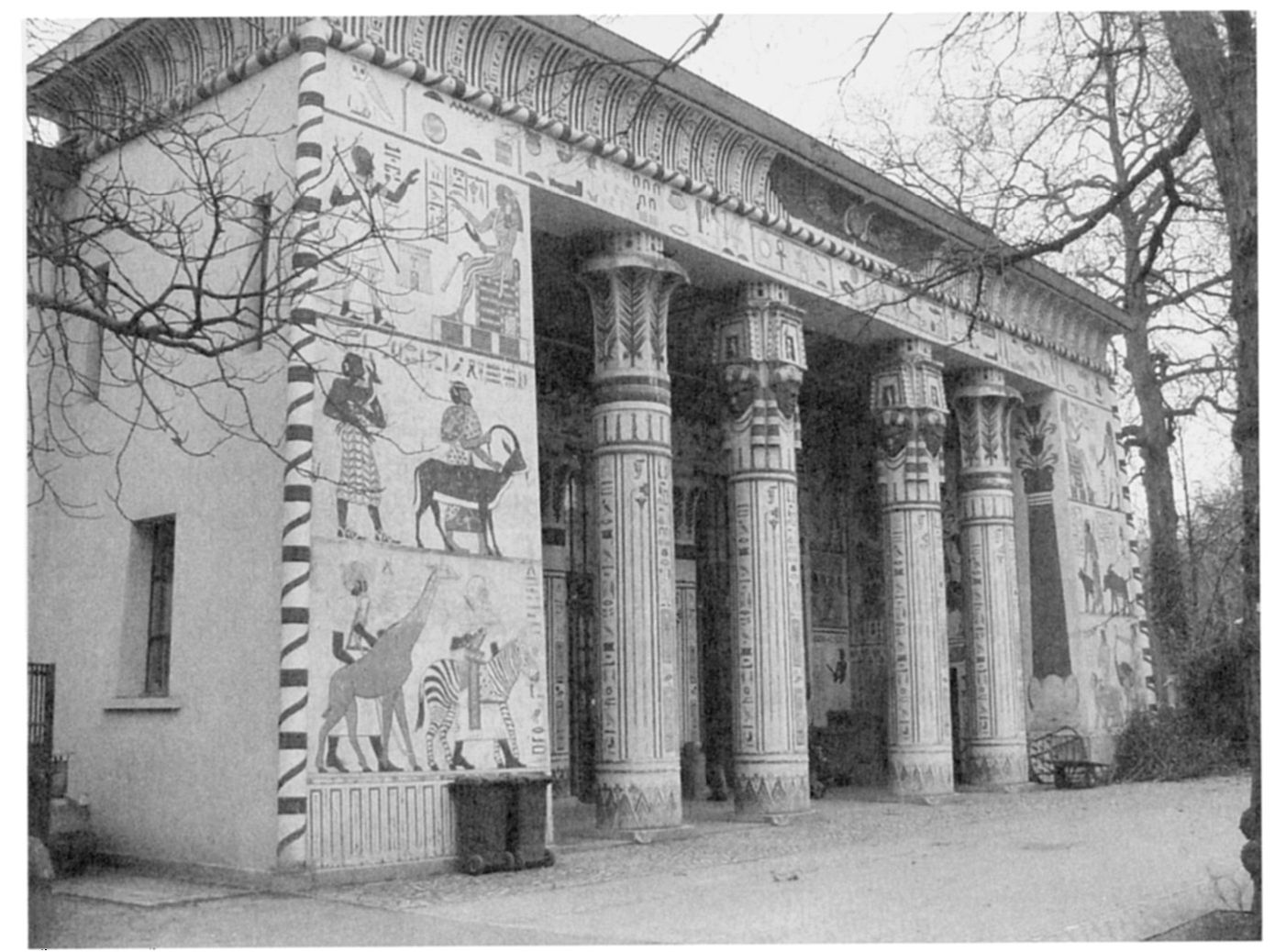

In recent years, many zoos have started to theme the way they exhibit animals and to display them in metaphorical rather than literal terms. Popular themes include the jungle/rainforest, the African savannah, and the zoo as conservation center. The ever-popular exotic scenarios with crumbling ruins or ancient architecture, as well as the now increasingly seen conservationists riding in jeeps on rescue missions, rely in part on imagery that is familiar to archaeologists (see figures 9.1 and 9.2; cf. Sanes 1996—2000a). Here, we encounter again the hero who braves adversity in foreign lands in his hunt for treasured objects (animals, artifacts). Disney’s Animal Kingdom near Disney World in Florida provides, for instance, the Kilimanjaro Safari through a simulated Africa. The journey takes an unexpected turn when the driver asks his passengers whether he should try to catch some poachers that have just been spotted from an airplane. A chase ensues through dense vegetation with machine-gun fire in the air, until they reach the poachers’ camp where guards arrest the villains and the riders emerge as ecoheroes (cf. Sanes 1996—2000b). There are other ways, too, in which visitors are encouraged to take part in “scientific” research. The new Erlebnis Zoo Hannover in Germany features a stranded jeep before visitors get to the empty camp of a primatologist’s field site next to the gorilla enclosure. At the Boneyard in Disney’s Animal Kingdom, children are invited to “dig up the bones of a woolly mammoth in the dig site.” Similar dinosaur excavations are evoked at many other zoos.

Figure 9.1 Who comes through the jungle? Indiana Jones? Lara Croft? Or an animal conservationist? Seen in the San Diego Wild Animal Park. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2000.

Figure 9.2 An Egyptian temple with hieroglyphic murals adds “archaeo-appeal” to Antwerp Zoo, Belgium. Built in 1856, it is used for the elephants. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2003.

As a consequence of foregrounding exciting experiences, zoos now compete successfully with popular attractions such as themed adventure parks and (natural) heritage attractions. In some cases, such as Disney’s Animal Kingdom and various Sea World theme parks in the United States, Furuviksparken near Gävle in Sweden, the already-mentioned Hannover Zoo in Germany, and Chessington World of Adventures in the United Kingdom, it is in fact difficult to draw the line between these formerly distinct categories (e.g., Sanes 1996—2000b; Davis 1995; Reichenbach 2000). They all keep exotic animals, and they all provide professional family entertainment. Given such trends, which may be described as a general “Disneyization” of family attractions, Alan Beardsworth and Alan Bryman suspect that the exhibition of animals might become subordinate to the staging of elaborate quasifications of the wild: “Rather than the animals being the primary attraction, the settings themselves will become the main objects of the visitor’s entranced and admiring gaze” (2001: 100).

The design of many animal cages and enclosures gives the impression that a natural habitat has been imitated for the benefit of the animals. But ever since Carl Hagenbeck’s innovations in enclosure design, it is in fact the visitors who were addressed by most of the scenery in which the animals are set while they are publicly visible, whereas backstage the animals have continuously been kept in very different conditions (see Berger 1980: 21-24; Croke 1997: 76-83; Mullan and Marvin 1999: 46-53, 78-79). This public scenery can occasionally have a strong historical dimension. The Wildwood Trust in Kent, England, for example, offers “an ancient woodland that dates back to the Domesday Book” and is now the home of animal species that “feature in ancient Saxon and Viking legends” and British folklore, such as wild boars, wolves, badgers, and ravens (www.wildwoodtrust.org).

Besides contributing to conservation schemes and joining scientific expeditions, zoos are expected to display appealing animals. There are a number of distinctive animal appeals resulting from cuteness, anthropomorphism, beauty, exoticness, or potential danger (Croke 1997: 95-100). Zoo settings, which used to be created to simply house the animals, are increasingly designed to actively facilitate the visitor’s sensations of such animal appeals. Touching cute animals, imitating those which remind us of humans, marveling at beautiful species, smelling exotic scents, and hearing dangerous creatures move or groan are what a successful zoo visit is all about.

The zoologist and writer Desmond Morris (1967) once investigated the various animal appeals of different species in a large survey involving eighty thousand British schoolchildren. He found that the popularity of an animal correlated directly with the number of anthropomorphic features it possessed, such as hair, rounded outlines, flat faces, facial expressions, the ability to manipulate small objects, and vertical posture (cf. Mullan and Marvin 1999: 134). It is no surprise then that over 97 percent of the children named a mammal of some kind as their favorite animal, and the six most popular animals were chimpanzees, monkeys, horses, bushbabies, pandas, and bears. Conversely, the most hated animals lacked such anthropomorphic features: snakes, spiders, and crocodiles. Relative to age groups, Morris found that, on the whole, younger children preferred the bigger animals, while older children preferred smaller ones. The explanatory interpretation he offered was that the smaller children viewed the animals as parent substitutes, and the older children looked upon them as child substitutes (Morris 1967: 226—38; see also Mullan and Marvin 1999: 24-28). The only exception to this rule was the horse, which was found to be especially popular among girls at the onset of puberty. Although some of Morris’s explanations may sound simplistic and crude, it is a fact that both animal-conservation programs and zoo displays are particularly geared towards large mammals, in general, and a few especially enigmatic species, known as “charismatic megafauna,” in particular (cf. Croke 1997: 181—85). This may have something to do with the reason people visit zoos: the encounter with charismatic wild animals.

The writer and critic John Berger (1980: 19) famously claims, “The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, to see them, is, in fact a monument to the impossibility of such encounters” and, thus, a necessary disappointment. But in a recent book titled The Modern Ark, Vicki Croke suggests that a “mysterious link between humans and animals” is made frequently in zoos (1997: 250), and that corresponds with my own experiences, too. Croke writes, “the visitor will almost always remember an intimate connection, a brief moment when the zoo animal looked up, followed or reached out.... That’s a magic that no camcorder or satellite can compete with” (1997: 250).

Similarly, Susan Davis (1995) discusses in her work on the Sea World theme parks how the show presentations of the killer whale Shamu try to establish emotional encounters of people with the other world of nature by successfully evoking feelings of awe, wonder, and joy. As Davis notes, some animals like Shamu appear to look back at the visitor, creating “magic moments” (see also Mulland and Marvin 1999: 19—23). The same special experience of making contact with an animal can be observed in children’s zoos, where the children may pet some animals. It is this thrill of experiencing charismatic wild animals close up that is the core of the zoo experience.

What Is Archaeo-appeal?

The message from zoos to archaeology is that a simulated participation in scientific practice and the magic of encountering enigmatic objects can provide visitors with very powerful experiences. They are even stronger when they are a part of themed environments that tell exciting stories, involving the visitor in metaphorical scenarios. These experiences are entertaining, but as visitors relate their impressions immediately to themselves, they can also be highly educational.

Archaeology is increasingly recognized as ideally suited for providing precisely these kinds of magical experiences through the encounter with both a fascinating scientific discipline and the remains of past human beings (see figure 9.2). A perfect example is JORVIK, the Viking age attraction in York in northern England (www.jorvik-viking-centre.co.uk, accessed October 4, 2004). Not presenting itself as a museum, but instead providing a ride into a fully reconstructed Viking town at the very site where it once stood and illuminating some of the underlying archaeological methods and techniques, JORVIK has attracted a staggering fourteen million visitors since it opened in 1984. It effectively pays now in perpetuity for the ambitious archaeological program of the York Archaeological Trust. Similarly, the Vasa Museum in Stockholm has become Scandinavia’s most popular museum by displaying the huge charismatic ship together with explanations about both its historical context and the archaeological sal- vage and conservation process undertaken since 1961 (www.vasamu-seet.se, accessed October 4, 2004). Other attractions address the public taste for archaeology in different ways, such as Disneyland, which embraced the broad appeal of Indiana Jones by theming its currently most popular ride about one of his archaeological film adventures.

Thesis 12:

Experiencing archaeological practice and imagining the past constitute the magic of archaeology.

Themed environments that draw on archaeological themes can be found in zoos, theme parks, commercial heritage attractions, restaurants, hotels, and shopping malls. They usually provide archaeological magic in much purer form than those attractions created by professional archaeologists and are therefore particularly interesting for understanding archaeology’s significance in popular culture. For example, one of the attractions of the Chessington World of Adventures is Tomb Blaster, which is also designed around the Indiana Jones theme (but without any of the trademarks) and involves the visitor shooting with laser guns. If you follow the evolutionary path at Hannover Zoo, you pass a simulated archaeological excavation site complete with skulls on a workbench and even a cave inhabited by a family of Neanderthals, before reaching the gorillas (Reichenbach 2000). Similarly, Furuviksparken in Sweden includes an adventure and education area dedicated to the well-known, but fictitious, Stone Age family Hedenhös, and the English Wildwood Trust is now planning to erect an entire reconstructed Saxon settlement. Behind this trend lies what might be called a particular archaeo-appeal that has long been associated with the image of the archaeologist, archaeological methodology, and archaeological subject matter as a whole (see also DeBoer 1999).

Archaeo-appeal is what makes people experience the magic of archaeology. That magic is to a large extent about the hero who travels into exotic settings and makes fantastic discoveries, usually underground, of authentic ancient objects that seem to bring him or her a little closer to the ancient people who originally made them and that sometimes, it seems, look back at us like Shamu. One important reason for archaeology’s general popularity and appeal is, then, that it embodies a number of very popular motifs of Western popular culture. Archaeology combines potent contemporaneous themes such as (scientific) progress, technological wizardry, and ever more “novel” discoveries, with nostalgia for ancient worlds, Utopias, and fantastic settings in exotic locations. Not coincidentally, these are precisely the themes out of which the fantasies of Hollywood, Las Vegas, and other themed environments are made (see Gottdiener 1997: 151—52). And arguably, academic archaeology succeeds as a discipline because it, too, is good in linking itself to some of the same themes, whether deliberately or accidentally.

Curiously, many archaeological exhibitions, displays, and presentations appear to rely on the archaeo-appeal they provide without actually addressing it explicitly. More often than not, they attempt to teach visitors literal facts about a specific past period or about scientific methodology and ignore the fact that many people come first of all in order to experience a range of popular metaphors. The large majority of visitors do not care much about what kinds of pots and pans people used at any point in history but are keen (for various reasons) to realize a little bit of their dream of being an archaeologist investigating ancient sites and getting closer to ancient worlds from their own position in the present. Good examples are archaeological open-air museums featuring demonstrations of various ancient skills and crafts, from building longhouses to baking bread and making pots. Many such displays are presented according to high academic standards regarding the precise period represented and the tools used, but for visitors it is often the reconstructive process itself that is significant, rather than what is actually represented.

An interesting question is whether an elementary archaeo-appeal and its associated experiences are actually similar worldwide and have existed at all times or whether they are highly context dependent and restricted to the modern Western world. This question clearly calls for further historical and empirical studies. But two things are fairly clear from the outset. First, many of the themes in which archaeology is implicated today have remained essentially the same since the beginnings of archaeology as an academic field in the eighteenth century. The process of finding treasure below the surface, the adventurous character of fieldwork, the method of inferring the past from clues, and the social construction of age and authenticity, for example, are equally applicable to Heinrich Schliemann’s times as to our own (see chapters 2 and 3; cf. Zintzen 1998).

Second, it is also clear that some of the innovations and social changes of recent decades in the Western world had profound effects on the issues discussed in this book. Gerhard Schulze (1993) argues that since the early 1980s we have been living in a society in which people increasingly live their lives for the experiences they can have. This could partly account for the particular boom of archaeology in recent years. Archaeology appears to offer precisely the kind of experiences that many people long for. Moreover, the contemporary mass media, the Internet, expanding tourism, and trends towards a global economy have no doubt been instrumental not only to the spread of themed environments and “Disneyization,” but also to the global popularization of archaeological themes such as those contained in the Indiana Jones-type hero and the Sherlock Holmes-type detective-scholar. These trends also contribute to the rendering of sites like Stonehenge in the United Kingdom, the Italian town of Pompeii, the Acropolis of Athens in Greece, or the Egyptian pyramids into global archaeological clichés that are equally ubiquitous in the popular culture of their home countries as they are (or might be) in commercial TV or in Las Vegas. Clichés such as these enable people to make even strange things understandable, enjoyable, and relevant to their own social context in the familiar present. Accepting that the past is of the present therefore also requires an engagement with the abstractions and schemata within which the past is actually understood in the present (cf. Schulze 1993: chapter 9).

Looking back in time, it emerges that archaeology has always been deeply immersed in the specific cultural contexts within which it has been practiced (see Schnapp 1996). This insight is neither new nor particularly surprising, but its consequences are far-reaching. If the past is essentially of each present (rather than merely in each present), historians and archaeologists cannot discover the cause-and-effect relationships that created the conditions of each present in the first place. Ancient remains, rather than places that can tell us something about the actual past, become sites at which certain themes and stories of the present manifest themselves. Their pastness is no longer borne out in any actual processes and events that took place a long time ago but in how they are perceived and experienced today.

Some might consider this view of the role of the past in the present and the implied altered status of archaeology as diametrically opposed to their own opinions on what archaeologists and historians should base their work on (e.g., Maier 1981). They may even consider it politically dangerous to hold views like these because of the implied denial of our present’s being part of a historical process and the resulting impossibility of explaining the present as a result of that process (e.g., Fowler 1994: 12—13). But for others, the possibility and necessity of historical change will derive much more naturally from analyzing current affairs, while explanations that rely predominantly on the present rather than the past avoid the danger of letting age and tradition stand in for rational justification.

Claiming that the past is of the present makes the past no less significant today. It paves the way for the assertion that the significance of the past is defined by all of us, rather than by the few who assume a position of intellectual authority from which they state how archaeological sites and artifacts are properly appreciated and ultimately what they really mean for us. At the end of the day, professional archaeologists must provide a service for society. They are therefore well advised to consider carefully how people actually (prefer to) experience archaeology, the past, and its remains and what particular archaeo-appeal different sites and objects may offer to their audiences (see also Merriman 2002).

A Very Brief Summary of the Argument

From Stonehenge to Las Vegas ranges a continuum of appealing archaeological themes. They are what this book has been about. I began with a theoretical argument that archaeology is mainly about our own culture in the present, rather than about past cultures, since what matters most about recalling the past is not whether people remember it accurately but who remembers what and how at any given point in time and space. Collective memories often imply a particular image of archaeology, and this is what I turned to next.

In popular culture, archaeology is about searching and finding treasure below the surface. The necessary fieldwork involves making discoveries under tough conditions and in exotic locations. As a detective of the past, the archaeologist tries to piece together what happened in the past. For many this process of doing archaeology is more exciting and important than its actual results. The three themes of searching for underground treasures, conducting adventurous fieldwork, and employing criminological procedures are culturally meaningful in a wide range of fields. They also come together in the aims, actions, and skills of the archaeologist and give him or her a special appeal.

Yet, as popular as archaeological practice may be, there are alternatives to it. A look at archaeological sites and artifacts in past and present shows that their meanings have varied enormously. Even today they mean very different things to different people. Often their significance is to a large extent metaphorical; that is, it does not reside in what they are but in what they are taken to be. All these meanings are equally important. Considering also that they are constantly changing, depending on who is looking at an archaeological site or artifact in what specific context, even the presumed authenticity of any such object comes to depend on the context of the observer. Perceived pastness thus becomes more important than actual age. The past is effectively remade in every present culture, and in this sense, it is a renewable resource. Archaeologists’ widespread preoccupation with preservation is arguably misplaced. There are indeed cases where much can be gained from effectively destroying an ancient site.

What matters most regarding archaeology’s social significance is the magic it conveys. Archaeology’s very special popular appeal is based on the experiences of doing archaeology and imagining the past, both often in metaphorical terms. Such archaeo-appeal is at the heart of archaeology and its ultimate reason and justification.

This does not mean that archaeology is necessarily uncritical and without a political edge. But archaeologists should not prescribe to other people how or what to think about the past. Instead, archaeology’s critical potential lies in the capacity to open people’s eyes, both in amazement at the magic provided by archaeology and through insights into the characteristics and significant implications of that magic, such as those explored in this book.

If archaeology is popular culture, then we are all archaeologists. That does not allow us to claim extra wages, but it does allow us to celebrate jointly the diverse meanings of archaeological sites and artifacts, from Stonehenge to Las Vegas, and to enjoy together the visions, thrills, and desires of doing archaeology. As I hope to have shown throughout this book, archaeology can create exciting and insightful moments in our lives. At its best it lets us sense the magic that can be derived from the experiences of both archaeological research and the past.