CHAPTER EIGHT

THE PAST AS A RENEWABLE RESOURCE

“This home is very historical,” they say. “But it was built only last year.”

—David Lowenthal (1994: 63, referring to F. W. Mote 1973)

I have argued that authenticity and pastness are constructed in each present. They are not properties inherent in any material form. This leads to the conclusion that each present constructs not only the past in its own terms but even the age and authenticity of the material remains of that past. Are the past and its remains, then, really nonrenewable resources as is often stated?

Is the Past Endangered?

It has become a cliché to lament the loss of ancient sites and objects in the modern Western world in much the same way as we do the continuous reduction of the tropical rainforests and the gradual decline of remaining oil reserves (cf. Lomborg 2001). Timothy Darvill argues accordingly that “the archaeological resource is finite in the sense that only so many examples of any defined class of monument were ever created.... The archaeological resource is non-renewable in that ... once a monument or site is lost it cannot be recreated” (1993: 6).

Similarly to the decrease of important natural resources, it has been reckoned that this generation has destroyed more of prehistory than was previously known to exist (Lowenthal 1985: 396). As a consequence, rescue archaeology and the preservation of ancient sites have become the order of the day. The UNESCO World Heritage Centre, for example, writes about its task:

With 754 cultural and natural sites already protected worldwide, the World Heritage Committee is working to make sure that future generations can inherit the treasures of the past. And yet, most sites face a variety of threats, particularly in today’s environment. The preservation of this common heritage concerns us all. (www.unesco.org/whc/nwhc/pages/sites/s_worldx.htm, accessed October 4, 2004)

But all of this could be beside the point. I argue in this chapter that we are not at any risk of running out of archaeological sites and monuments and that future generations of people will never be without “treasures of the past.” The cultural heritage does not disappear steadily in the same way the ozone layer or the rainforest do, for two reasons.

First, in absolute terms we are arguably not actually losing but gaining sites. No other societies have surrounded themselves with as many archaeological sites and objects that can be experienced in the landscape or as part of collections as our modern Western societies. Typical for the Western world is not the loss of archaeological sites and objects but their rescue and subsequent accumulation in museums, archives, or the landscape. Even archaeologists themselves will agree that the rapidly growing numbers of archaeological sites and objects creates considerable challenges for responsible heritage management and the archiving of finds, making it difficult to keep up with the overall task of “writing history” (Tilley 1989b). In relation to the huge accumulation of data from extensive rescue work, we are arguably the victims of our own success. If there is any problem concerning the preservation of archaeological sites and objects in the modern Western world, it could therefore be that we are overwhelmed by the sheer number of them. This problem has been building up for some time and exists equally in the United States and in Europe (see Thomas 1991; Robbins 2001). In 1995, England alone (not the United Kingdom as a whole) had more than 657,000 registered archaeological sites, an increase of 117 percent since 1983, and its archaeological site and monument records were expected to contain over one million entries by the end of the millennium. Between 1983 and 1995, on average nearly one hundred entries were added to the records daily, while only one recorded site per day has been lost since 1945 (according to Darvill and Fulton 1998: 4-7). The trend is therefore not that we will one day have no archaeological sites and finds left, but that in the future more and more of our life-world will be recorded and stored as some sort of historical object worthy of appreciation and preservation.

Second, far more important than counting the number of preserved or destroyed sites or objects is ensuring that the benefits the cultural heritage offers to people remain available to future generations (for similar arguments concerning natural resources, cf. Krieger 1973; Lomborg 2001: 119). Before lamenting loudly any losses, it is therefore pertinent to ask what we need the cultural heritage for. Different purposes may be fulfilled by different kinds of sites, and even though we are not in danger of running out of ancient sites completely, we may be in danger of running out of particularly valuable sites. This possibility clearly warrants further study. Here, I show, however, that both archaeologists’ and nonarchaeologists’ appreciations of ancient sites are not directly related to any specific amount of preservation and may not require the preservation of many original sites at all.

One of the benefits of cultural heritage is often said to be the possibility of appreciating the historical roots of our present, thereby cultivating a critical historical consciousness (e.g., Wienberg 1999: 191). But if anything, the reverse is true: cultural heritage is not the origin but the manifestation of a historical consciousness and various specific appreciations of the past. As a cultural construct the past does not necessarily rely on great numbers of original archaeological sites or objects. Their significance for our understandings of the past depends largely on the wider sociocultural contexts within which they are given value, meaning, and legal protection (see Leone and Potter 1992). Every generation constructs its own range of ancient sites and objects, which function as metaphors that evoke the past. Certain pasts may not even directly relate to physical remains of the past at all (see Layton 1994).

Over the centuries, many novel pasts replaced others. The sociologist George Herbert Mead states, “Every generation rewrites its history—and its history is the only history it has of the world“ (1929: 240). With every new past, new archaeological and historical sites and objects are created or become significant in relation to this past. Others become redundant and eventually disappear. This may be sad, but only in the way that the autumn is sad (Vayne 2003: 15). As the eminent economist Alan Peacock phrases it, “we should not assume that the ‘non-reproducible’ is necessarily ‘irreplaceable’” (1978: 3).

Thesis 10:

The past is being remade in every present and is thus a renewable resource.

As far as our own present society is concerned, one can gain the impression that “archaeological material is not protected because it is valued, but rather it is valued because it is protected” (Carman 1996: 115). This view is similar to physicist Martin Krieger’s (1973) argument in an infamous Science paper regarding the natural environment. He claims that the way Americans experience nature, including “rare environments,” is conditioned by their society and the result of conscious choices about what is desired, followed by investments and advertising to create these desired experiences. The interventions that create these rare environments in the first place can also create plentiful substitutions.

To complicate matters further, at any one time there are various parallel pasts with their own set of meaningful archaeological sites and objects. John Tunbridge and Greg Ashworth argue in respect to modern society

there is an almost infinite variety of possible heritages, each shaped for the requirements of specific consumer groups.... An obvious implication that needs constant reiterating is that the nature of the heritage product is determined ... by the requirements of the consumer not the existence of the resources. (1996: 8, 9)

What constitutes an ancient site or object for some may not necessarily do so for others, who may consider it fake, misinterpreted, or unscientific. Preservationists, druids, New Age followers, archaeoastronomers, ley hunters, political parties, and others each reinvent the past in their own terms and with reference to their own selection of especially significant ancient sites and artifacts, which can be very different from those of academic archaeology. In each case the selection of objects follows from the perspective taken and not vice versa.

Another kind of social benefit of the cultural heritage is that they give people the possibility of permanently rescuing them. In some cases, documenting and saving remains of the past has become more important than what is actually documented and saved (see chapter 4). Luckily, we will not run out of savable ancient sites any time soon, and archaeology can therefore remain significant as a practice of documentation, preservation, and rescue for a long time to come. Wildlife conservation plays a similar role, and it is occasionally informative to connect the two discourses of archaeological and natural conservation. Charles Bergman, a professor of English specializing in environmental writing, observed recently that the cultural significance of wild animals is in part linked to the category “endangered”: “We like animals because they are endangered.... We don’t want animals do go extinct. Nor do we want them abundant. We want them endangered.... Endangerment signifies a category in which animals are known by their perpetual disappearing” (2002).

Their marginal state of existence gives these animals one of their characteristic values—and it gives humans the opportunity to contribute to their perpetual rescue. What matters a lot in nature conservation, as in much of cultural-heritage management, is the metaphorical significance of what lies beyond our everyday surroundings. Insofar as they have a strange appearance, remote origins, and their numbers are threatened, both animals and artifacts can become exotic rarities. People enjoy helping them to survive as such but would not want them to become too common.

Other benefits of cultural heritage include pragmatic effects (they generate income and create jobs) and political functions (they help build collective identities and support ideologies). Copies and reconstructions need to be made and managed too, though. And they too can be used for social and political engineering, signifying a range of valued metaphors. All the benefits mentioned so far, therefore, do not straightforwardly depend on the extensive preservation of a given, large assemblage of cultural heritage.

But what about the benefits of preserving archaeological sites and objects for the benefit for future generations of archaeologists who will be able to employ improved methods and, therefore, learn a lot more about the past? Arguably, large numbers of preserved archaeological sites are not as essential for scientific research as is often stated. This is not because I trust that we can record them “in full” at the time of their destruction or because I believe a small sample of sites would in any case be representative. Rather, I am inclined to think that the success of archaeology is determined by how satisfactorily the norms of its craft, or discourse, are exercised in practice and not by some objective measure of how close we have come to an understanding of the “real” past (cf. Shanks and McGuire 1996). In other words, archaeologists will be happy to do their fieldwork and analyze site and monument records with ever-new questions and methods, to write smart academic books and papers, and to teach their students, no matter how many archaeological sites are left at their disposal. Indeed, it may even stimulate research and interpretation if the amount of data available is limited rather than overwhelming. At least in informal discussions this is sometimes given as the reason for the greater willingness of prehistorians to concern themselves with interpretation and theory than, for example, classical or historical archaeologists.

At any rate, what benefits in the present are we prepared to sacrifice for the good of future generations? On what basis can anybody deny present communities the right to use their heritage however they see fit? It is quite impossible to know and is, perhaps, a peculiar kind of arrogance to assume that future generations will be grateful to us for preserving vast amounts of ancient material culture (Moore 1997: 31). It is also politically, economically, and ethically debatable whether it is right, despite many urgent present-day needs and various legitimate interests in consuming ancient sites, to spend tight public resources on future generations’ presumed interests (cf. Merriman 2002). Their preferences will by definition always remain unknown since the future can never be present. But if one wants to risk any prediction at all, they are likely to be materially better off than we are today and thus economically less deserving than we are ourselves, Alan Peacock (1978: 7) has asserted. Moreover, it may arguably be counterproductive to preserve too much for future generations since they may perceive as less valuable what is less rare and thus be less appreciative and careful than they would otherwise have been, effectively rendering our conservation efforts meaningless (Krieger 1973: 453).

Experiencing the Past

Michael Shanks (1995) has claimed that archaeology, like heritage, is largely a set of experiences. Simulated environments can provide us with fabricated, but nevertheless real, experiences of both the “authentic” past and archaeology (see chapter 7). Their realism is not that of a lost, real past but of real sensual impressions and emotions in the present, which engage visitors and engender meaningful feelings (see Bagnall 1996; Hjemdahl 2002). Among the most powerful “archaeological” events, sites, and objects evoking the past in our present without being able to withstand a scientific dating test are

- Models and dioramas in exhibitions

- Virtual reconstructions in computer games (cf. Watrall 2002)

- Facsimile reprints of ancient texts and replicas of artifacts, such as those for sale in tourist shops and museums (figure 7.2)

- Art installations in the tradition of the Spurensicherung (see figures 4.1, 4.2, and 4.4)

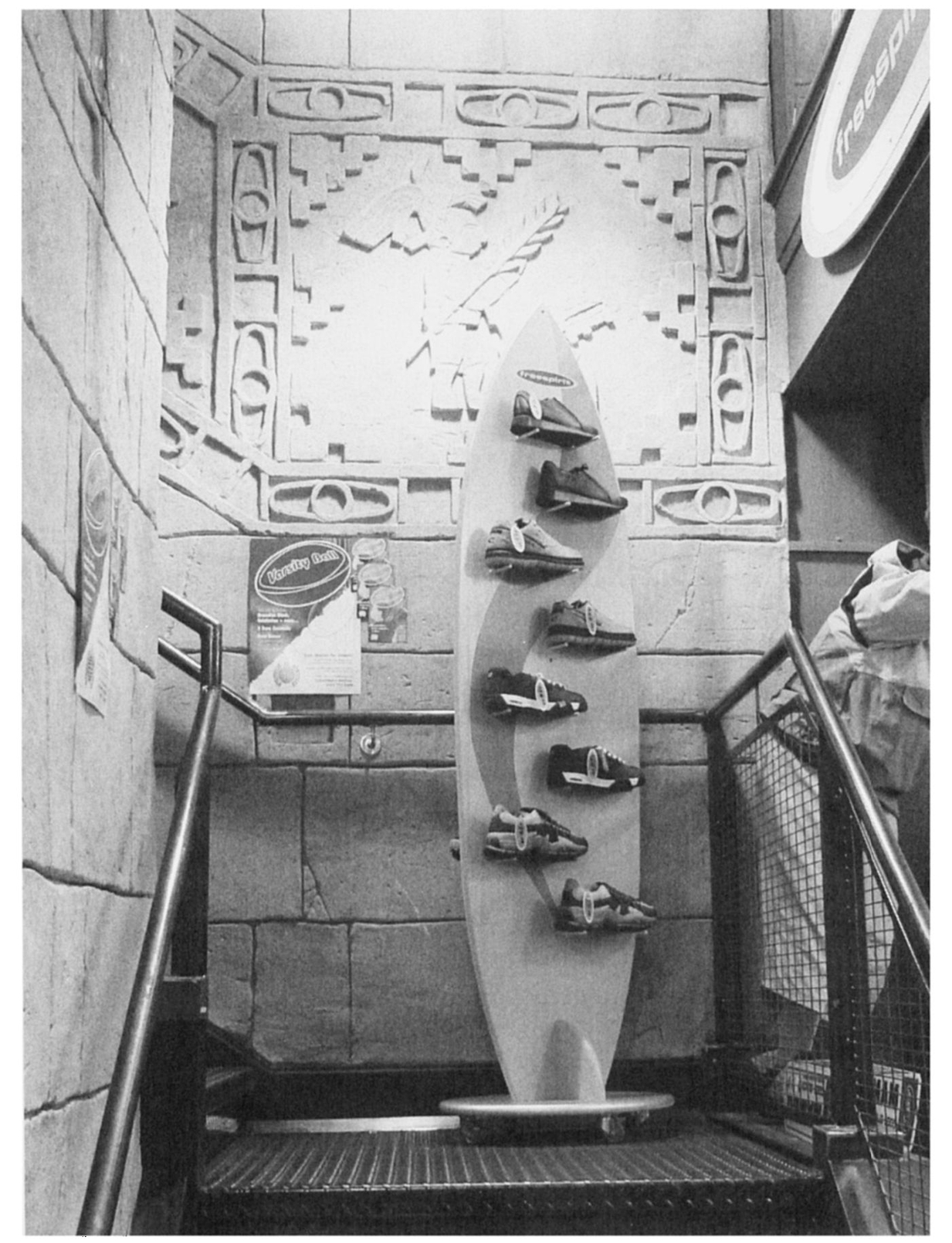

- Souvenirs, retro-chic, and other items of popular culture that draw on designs evoking the past (figures 7.3 and 8.1; cf. Loukatos 1978)

- Living history, historic plays, and reenactments of past events, either live or on film (cf. Samuel 1994: part II; Gustafsson 2002)

- Restored or reconstructed archaeological heritage sites such as Stonehenge and the fast growing number of archaeological open-air museums (figures 5.2, 6.1, 6.2, and 7.1; cf. Petersson 2003)

- Artificial ruins, Egyptian and Greek temples in landscape parks and zoological gardens from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (figure 9.2)

- Reconstructed buildings and entire town districts, as in the Polish cities of Warsaw and Gdansk (see chapter 7)

- Reenacted traditions such as the annual initiation ceremony of the Welsh Gorsedd of Bards performed in modern stone circles

- Rebred, formerly extinct animal species such as the Przewalski horse

- Neo-Gothic, neoclassical, and certain elements of contemporary postmodern architecture, mostly in America (e.g., in Las Vegas, see front cover; cf. Lowenthal 1985: 309-19, 382-83; Dyson 2001)

Some of these elements also occur both in Disneyland and in the themed hotel-casino-shopping malls of Las Vegas. The range of Disney products in particular is interesting here since they are not only very popular but also very experience-oriented. Moreover, Disney products provide potent imagery about the past (cf. Fjellman 1992: 59-63; Silverman 2002). The American public historian Mike Wallace (1985: 33) speculates in an often-cited essay that Walt Disney through his theme parks may have taught people more history, in a more memorable way, than they ever learned in school. Behind the success of Disney are a number of more general principles that have now come to dominate more and more sectors of society. The British sociologist Alan Bryman (1999) distinguishes four such increasingly influential principles.

Figure 8.1 Maya art in central Cambridge, United Kingdom. Staircase in the sportshop Freespirit. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2001.

- Theming: the use of imagery to which people can easily relate and which immerses them in a world different from the normal routines and restrictions of everyday life. Such metaphorical elsewhereness is not only exciting in itself but also carries the implication that there are different rules to observe and different responsibilities to attend to (see Hopkins 1990; Köck 1990). Theming is increasingly important for shopping areas, restaurants, hotels, golf courses, and even entire city centers, not just in Las Vegas (see Gottdiener 1997; Beardsworth and Bryman 1999). Board games and toys are often themed too (see, e.g., figure 3.3). Even entire countries are theming themselves in their attempts to attract tourists, transforming modern travel from an encounter with other cultures into an experience of attractive metaphors.

- Dedfferentiation of consumption: forms of consumption associated with different institutional spheres that become interlocked with each other and are increasingly difficult to distinguish. For example, as Disneyland and Las Vegas illustrate, the distinction between hotel—shop—amusement park-theme park is disappearing. Theme parks have hotels and house shops, casinos incorporate hotels and museums, and shops are increasingly themed and can provide various kinds of amusements, slowly transforming them into tourist attractions in themselves (see Hopkins 1990). Traditional tourist attractions like museums and heritage sites, on the other hand, rely increasingly on revenues generated by their shops.

- Merchandising: promotion of goods connected with copyrighted images and logos. While Disney throughout his business empire has led the way in marketing logos and characters by carefully controlling all rights to them, similar merchandising techniques have now spread to various restaurant chains (such as the Hard Rock Cafe) and even to universities. I still occasionally get special offers for branded products from the University of Reading where I was a visiting student fourteen years ago.

- Emotional labor: employers seeking to control their workers’ emotions. The insistence that workers have to exhibit cheerfulness and friendly smiles towards customers at all times is as common in Disneyland as it is in McDonald’s restaurants and a range of other (American) shops.

As a result of these four principles at work, consumption is increasingly linked to signification, lifestyle, and identity (Gottdiener 1997: 153— 54). The powerful associations and positive connotations of archaeology as the adventure of investigating the human past may be able to account for its ubiquity not only in Disneyland’s Frontierland and Adventureland, but also in other Disneyfied areas of contemporary society like museums, shops, and hotels. Disneyland’s own most archaeological attraction is the exhilarating Indiana Jones Adventure ride based on elements of the movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Disneyfied history is qualitatively different from school history: it improves the past and represents what history should (!) have been like; it celebrates America, technological progress, and nostalgic memory; it hides wars, political and social conflicts, and human misery (cf. Wallace 1985; Fjellman 1992: chapter 4). Arguably, Disney history is false in as much as it is highly selective and simplistic rather than balanced and suitably complex; it is celebratory rather than critical; and it is profit oriented rather than educational. It is true that in final analysis, Disney “magic” serves to hide the commercial interests of a huge and very profitable business. It is therefore easy to dismiss Disney theme parks and Disneyfied attractions elsewhere as the capitalist American way of commodifying our lives and manipulating our knowledge of both the past and the present.

It has been argued that such sites fool people, not merely by giving them the impression of something that is not what it seems, but mainly by perfecting a fantasy world of fakes, which is more real than reality (“hyperreal”) and manipulates our perceptions, desires, and preferences (cf. Eco 1986; Fjellman 1992; Sanes 1996-2000a, 1996—2000b). This view, however, does not take the actual human experiences seriously enough. For, whatever purpose theming may serve, it still provides experiences that relate very closely to people’s desires and identities. Disney heritage is clearly fabricated, but it has the virtue that a large part of the public loves it. This is significant, for theming has to be appreciated as a part of people’s lived realities (cf. Bruner 1994; Lowenthal 1998). People are not tricked into believing in these worlds as alternatives to reality. Disney visitors are not fooled or misled. They are never made to believe that they are in any other period than the present. They always know that they can rely on the achievements of modernity: punctuality, physical safety, comfort, reliability, efficiency, cleanliness, hygiene, and the like are guaranteed.

Instead of insisting that themed environments provide illusions and hyperrealities, it is therefore more appropriate to see them as what sociologists Alan Beardsworth and Alan Bryman (1999) call “quasifications”: they invite the visitor to experience them as if they were something other. Consumers can thus “‘pretend’ that they are embroiled in an experience that is outside the modern context, but which is in fact firmly and safely rooted in it” (Beardsworth and Bryman 1999: 248-49). According to this theory, theming works so well precisely because people know that they are in artificial environments saturated by metaphors: they enjoy marveling at evocative relics and convincing fabrications, especially when they recognize the experience created (or indeed parodied) and the general way in which it is done (see, e.g., McCombie 2001). People enjoy feeling that they are somewhere and sometime else than where and when they actually are.

The authenticity of that experience is sustained by an “emotional realism.” Gaynor Bagnall (1996) argues that this emotional realism is underpinned by a desire for the experience to be genuine and based in fact. But many people neither seek historical veracity in themed environments nor mind its absence. They simply enjoy the sensual stimuli and experiences of imaginary spaces (cf. Hennig 1999; Hjemdahl 2002). Contrary to Bagnall’s conclusions, a superficial appearance of factuality that is not actually believed can be sufficient to ensure emotional satisfaction.

People particularly enjoy experiences that bring them close to something they recognize from their collective imaginations and fantasies. Experiences of elsewhereness and otherness can thus be created by drawing on “virtual capital” that consumers derive from mass media such as cinema and especially television (see Hennig 1999: 94—101; Beardsworth and Bryman 1999: 252). This link has many manifestations, from stereotypical natural habitats as they are recreated, for example, in our zoos to the clichés presented in historical reconstructions and “living history” (see Gustafsson 2002: chapter 6). For example, one of the best-known, widely used images representing the Roman world in Western popular culture is that of the chained galley slave, even though this notion is demonstrably false and owes its popularity to the Ben Hur novel and films (James 2001). The dreamworld of Las Vegas works in a similar way. The sociologist Mark Gottdiener (1997: 106) observed from a single vantage point in the streets of Las Vegas as many as half a dozen widely shared cultural clichés that we can all relate to media such as the Discovery Channel and National Geographic Magazine: a giant Easter Island sculpted head, an immense lion, a huge medieval castle, and a giant Sphinx in front of a pyramid.

One way in which Disney creates its magic is by using precisely such stereotypes that people respond to without thinking: although no one has ever lived in the past, everybody knows what it looked like (cf. Mitchell 1998: 48). Fred Beckenstein, a senior Euro Disneyland manager, appropriately said in an interview, “we’re not trying to design what really existed in 1900, we’re trying to design what people think they remember about what existed” (cited in Dickson 1993: 34). This is also born out in the Disney movie The Emperor’s New Groove (2000), which portrays the ancient Inca culture in Peru but draws in its imagery on a wide range of recognizably pre-Columbian or merely exotic, largely non-Inca and pre-Inca motifs (Silverman 2002). Taken to the extreme, what is fabricated in such a manner can thus seem more authentic and more valuable than what is actually ancient (see chapter 7).

From a purist point of view this may be very sad. But highly segmented markets require a focus on what is known to appeal in order for products to satisfy a large-enough proportion of consumers to be commercially viable (see Gottdiener 1997: chapter 7). In other words, for themed environments to work, their themes must be broadly consistent with the existing knowledge of the consumers. They will thus usually refer to tried-and-tested motifs of Western popular culture. That is why even the (in)famous, historically false, horned Viking helmet still has a certain legitimacy. As Alexandra Service argues in her study about the Vikings in twentieth-century Britain,

To survive as something that people care about, as the inspiration and focus for re-enactment, novels, merchandising and theme restaurants, it is necessary to be memorable, to stand out from the crowd. There must be the potential for excitement, and for escape from humdrum reality. These are qualities which the Viking myth supplies in abundance.... So the Vikings’ mixed reputation, horned helmets, red and white sails and all, live on. (1998b: 245-56)

Archaeological themes and icons such as those mentioned here renew the past in our time. In none of these examples is an explicit claim about true antiquity made, but they appear to be fully satisfactory in supplying many people with “authentic” experiences of the past and in satisfying most of our educational, economic, aesthetic, and spiritual needs, among others. In a similar vein, Andreas Wetzel argues that archaeological ruins allow and invite visitors to construct an image of the past, but the “actual physical historicity is of absolutely no relevance” to their effective significance in the present (1988: 18). This implies neither that people are victims of deliberate deceptions nor that they are superficial fools (cf. Cohen 1988). The ancient sites and objects archaeologists are normally dealing with do nothing other than renew the past in the present, too, often evoking potent metaphors. The value of archaeology in popular culture lies for the most part not in the specific results of its scholarship but in the degree to which it is linked to both the experience of pastness and to the grand themes of doing archaeology, as discussed in earlier chapters. In most circumstances, accurate factual details as such are far less important than the bigger impressions conveyed and the overall imagery evoked.

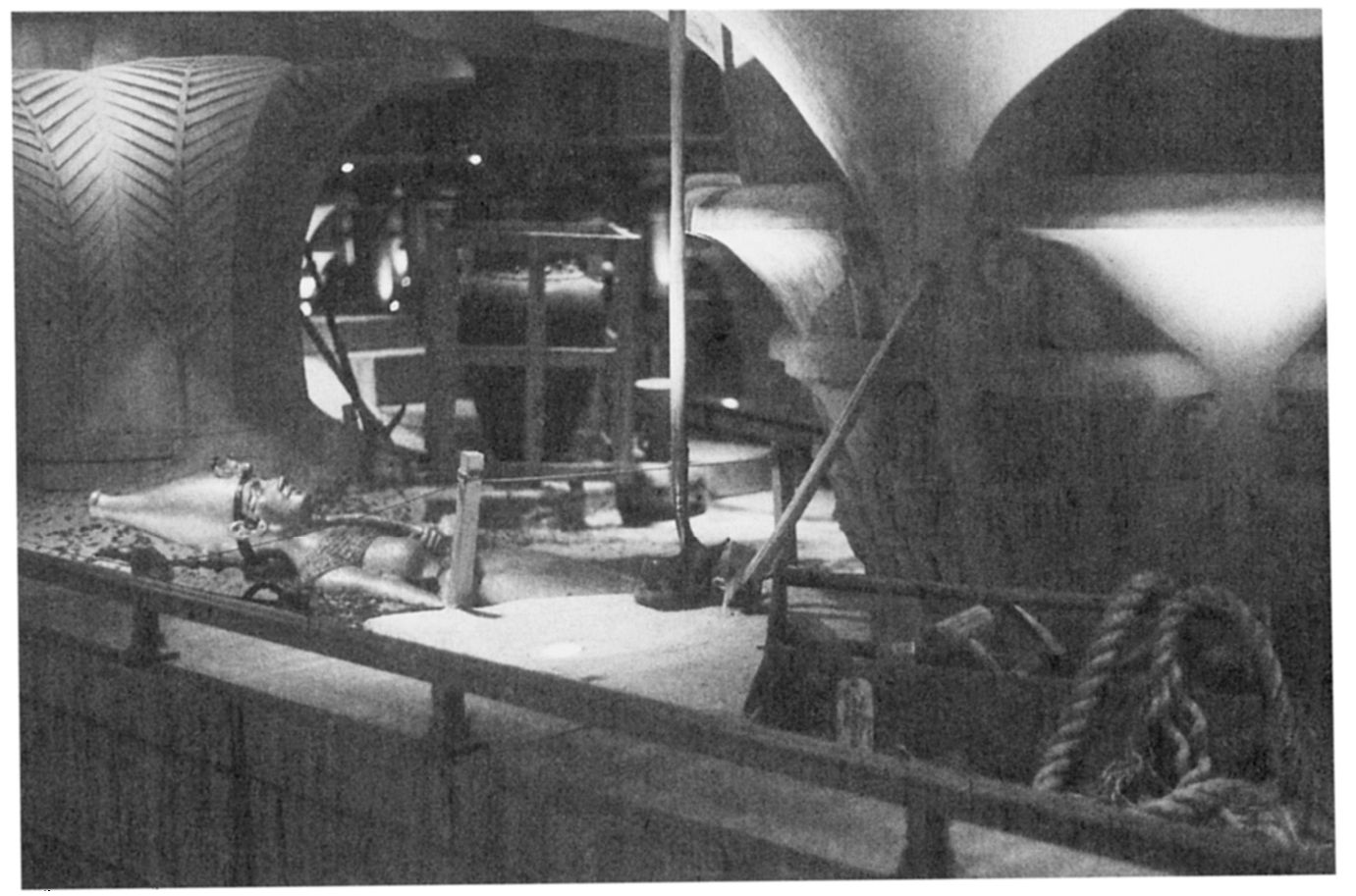

Figure 8.2 The large buffet restaurant “Pharaoh’s Pheast” in the Luxor hotel/ casino is seemingly next to an ongoing excavation of Egyptian treasures where the archaeologists have just gone for lunch. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2001.

Archaeology at Las Vegas

An extreme example of the proliferation of themed environments is provided by the very successful and profitable hotel-casino-shops in Las Vegas. They metaphorically transport the customer into some other world, removed from daily life and its conventional responsibilities and controls, encouraging fantasy and, of course, spending which is really the point.

Caesars Palace opened in 1966 as the first Las Vegas resort to embody consistently an archaeological or historical theme. It signifies the popular myth of a decadent and opulent Rome associated with excess and indulgence as it is depicted in movies like Ben Hur, Cleopatra, or Gladiator. Arguably, Caesars Palace creates a museum for the mass audience, a museum free of admission fees, velvet ropes, and Plexiglas panels and (falsely) appearing to be free even of omnipresent security guards (McCombie 2001: 56; cf. Schulze 1993: 142-46). Its architecture and design bear the signs of historicity but lack the tedious labels. The hotel-casino is a carrier of culture without many of the explicit behavioral constraints and class implications found in many ordinary museums. It invites the visitor-customer even to relive the past. Jay Sarno, the original owner of Caesars Palace, reportedly claimed, “We wanted to create the feeling that everybody in the hotel was a Caesar” (hence, there is no apostrophe in Caesars; Malamud 1998: 13). Margaret Malamud recognized this as one version of the American Dream: “it offers each guest the chance to transcend economic constraints and social barriers; and the design, facilities, and amenities at the Palace promise glamour, the fulfillment of desire, wealth, and power” (1998: 14).

Almost the same might be same about the Luxor, a more recent Las Vegas resort. Here, too, an atmosphere of exotic luxuriousness is created to stimulate spending. Completed in 1993 in the shape of the world’s largest pyramid and with a gigantic sphinx in front of it, the Luxor embraces the clichés of ancient Egypt, incorporating the pyramids, pharaohs, mummies, occult mysteries, fabulous wealth, and archaeological excavations. An “authentic” reproduction of Tutankhamun’s tomb as it looked when Howard Carter opened it in 1922 lets the tourist slip into the role of the archaeologist discovering wonderful things (Malamud 2001: 35). The main lobbies of the building are filled with full-scale Egyptian architecture, and in each room walls, wardrobes, and bed linen are adorned with Egyptian-style murals and hieroglyphics. The local What’s On journal even proclaims the Luxor to be “as much a museum as it is a hotel and casino.” A fact sheet available in the hotel in 2001 stated not only that “all ornamentation and hieroglyphs are authentic reproductions of originals” but also that “our ten-story tall Sphinx is taller than the original Sphinx.”

Constructive Destruction

If the experience of the past can somehow take the place of the past itself, what does this imply for the conservation and preservation of ancient sites and artifacts as two traditional objectives of archaeology and heritage management?8 They lose some of their currency and significance.

Ironically, modernism with its fetishization of the new and its desire to shape ever-new futures has also been characterized by a particular obsession with maintaining supposedly unchanging and objective monuments of the past (see Samuel 1994: 110; Fehr 1992: 54-56). All was to be modernized, apart from the remains of the past that needed to be preserved as they were. But the dualism between preservation on the one hand and modernization or modern usefulness on the other is in fact misleading. Not only are many preserved archaeological sites highly efficient modern heritage sites, but the ongoing project of modernity has also been producing ever more documented archaeological sites and artifacts. If it were not for various destructive processes carried out in the name of modernization, such as development, deep plowing, and war, many sites and artifacts would have remained unacknowledged in the ground until they had completely decayed; in effect, they would not have existed for any archaeologist to study. Even within the philosophy of modernist archaeology, it is thus commonly accepted that sites may be destroyed, layer by layer, and artifacts removed from their depositional contexts, as long as all of this is being replaced by records, which are archived for the benefit of the archaeological discipline (see Lucas 2001a: 159). Although most of what is uncovered still ends up on the spoil heap, archaeologists find this practice perfectly acceptable and a price worth paying for being able to contribute to the grand project of modern archaeology.

Many archaeological sites and artifacts, however, are not normally allowed to be damaged in any way so that, it is said, they can keep their value. But the link between keeping certain values and preventing damage is not as straightforward as it may seem. Irrespective of the fact that the often-necessary preservation of artifacts or sites can be a destructive process in itself (cf. Wijesuriya 2001), fundamental conflicts between intended preservation and desired use may arise. As the history of Stonehenge as a tourist destination and meeting point illustrates (see chapter 5), certain genuine uses of a site may be considered adverse to its material preservation.

Yet, what some would call “destruction” might simply be a way of appreciating a site in a way others are not used to, possibly preserving its long-standing function and character. The South African archaeologist Sven Ouzman (2001) showed, for example, how southern African rock engravings were traditionally hammered, rubbed, cut, and flaked. Such practices allowed people to produce sounds, to touch numinous images and rocks, and to possess, even consume, pieces of potent places. To our own predominantly visual culture, it seems foreign, even regrettable, that such sites are being “diminished” in this way. But arguably, the engravings were always part of lifeways that are less sensually impaired and less fixated on material preservation than our own, and what was a loss to us was a gain to others. By the same token, the comprehensive restoration and rebuilding of ancient stupas (repositories for a relic of the Buddha) in Sri Lanka until the twentieth century may have been detrimental to the ancient buildings for some but was religiously highly significant for those involved (see Kemper 1991: chapter 5; Byrne 1995; Wijesuriya 2001).

Stopping such traditions means interfering with people’s genuine engagements with the past and the constructive creation of their own heritage. Preservation of the original substance would in effect create a different kind of site and a different kind of past, preventing these practices from taking place in the future. Destruction is thus not necessarily fundamentally different from preservation as both processes transform a site with certain aims. Even in the Western world, the conservation ethic constitutes a radical departure from a long-standing previous historical practice and may, by implication, at some point give way to an alternative set of values yet again (Byrne 1995: 275). Arguably, therefore, the principles of modern preservationism themselves provide an example for how the past can be renewed in a particular present.

It is important to recall that the life history of archaeological sites and artifacts includes all kinds of reinterpretation, reuse, vandalism, or other modification, whether in the name of destruction or preservation (see chapter 5). They are historically equally significant. The former editor of Pagan News magazine, Julian Vayne (2003: 14), expresses this point particularly well: “The history of the site is not ‘damaged’ when something is added or taken away. If I lose [or remove!] a button from my coat I have not ‘damaged’ its history. History is not a fixed thing but a continuum, a process.”

How ancient sites or objects have been treated has always depended on the people involved and their particular preferences and agendas, much like today. Yet, since you cannot treat one and the same object in two different ways at the same time, it is impossible to please everybody. Hammering and flaking rock engravings cannot be combined with conserving the very same rock surfaces for the future. The anthropologist Mark Johnson (2001) discussed the same difficulty at the example of the World Heritage site of Hue in Vietnam. For UNESCO and possibly most visitors to Hue, the disappearance of buildings is seen as a problem when caused by humans, for example as a result of war. Yet when due to natural processes, decay is accepted and even valued as evidence of the natural locatedness, the romantic appeal, and the age-value of the site. But for a significant minority of visitors, U.S. Vietnam veterans, it is precisely the rubble of war that is most valued and appreciated at Hue. Using this example, Johnson argues that destruction is an inevitable part of every (re)construction, whether it is material or merely in our minds. You will always lose some things and gain others, although people may disagree strongly about the relative merits of the various possible actions taken. Johnson, thus, effectively relativizes destruction and calls for all claims to places, sites, and histories to acknowledge and account for the silences, suppressions, and vandalism that go together with their particular (re)constructions and representations (2001: 89).

A similar argument can be made regarding artifacts from ancient sites: in being physically altered or moved from one context to another, they lose some qualities and gain others. For example, as part of my personal collection of mementos and “things,” I own a Punic arrowhead from Segesta on the southern Italian island of Sicily, which I received as a Christmas present in 1984. Clearly, this has got to be either a fake or an illicit antiquity. But that made little difference to me back then, as this little token of Carthaginian history was for years an item of great pride and metaphorical significance to me. I have always felt uneasy about owning a single mosaic stone from Ostia in Italy, which I took with me as a souvenir during a visit in 1987. What was I thinking, just one year before I began studying archaeology at university? Today, I am confident in admitting my satisfaction about actually possessing a piece of ancient Ostia, which is authentic because I picked it up myself (or were the managers of ancient Ostia more cunning than I thought?). Yes, if every visitor did the same, in a matter of years there would not be much left of sites like this. But in another sense it would also mean something quite wonderful, that a site continues to exist despite being delocalized, distributed in the minds and on the shelves of so many proud tourists around the world. I also own a tiny piece of the Berlin Wall which I collected back in January 1984, sneaking onto German Democratic Republic territory, which started one meter in front of the wall, and scraping with my fingernails. Since then, of course, the unique value and aura of this piece has been somewhat reduced by the historical events of 1989 and their material implications. The Berlin Wall has indeed become a fine example of a historical site of great sig- nificance that has now largely disappeared from its original location and whose parts have been dispersed around the world, each one making a considerable impact in its new context. I value all these pieces for the contexts within which they were recovered and collected, and the memories of my teens that I associate with them.

Thesis 11:

In some cases much can be gained from effectively destroying an ancient site.

It is incorrect and somewhat naive to insist that looting makes ancient artifacts archaeologically as good as worthless by forever disassociating them from their precise original context within the given stratigraphy of the archaeological site from which they derive. This is a position that can only be understood within a very specific Western, academic way of thinking anyway. In fact, it is exactly these artifacts’ precise, original context that makes them valuable as archaeological commodities and lets them become so significant as authentic artifacts in the new contexts of peoples’ lives, to an extent that artifacts processed by an archaeological project and remaining in the public domain will struggle hard to even approach (see Byrne 1995: 276-77; Thoden van Velzen 1996; Ucko 2001; Stille 2002: chapter 3). Although illicit tomb robbing can harm all sorts of local, nonacademic interests too, it is impossible to condemn all destructions of archaeological sites or objects categorically. In the cases just mentioned and related to the above-mentioned war-damaged Hue, southern African rock engravings, Sri Lankan stupas, and archaeological excavations generally, destructive activities can be seen as potentially having also (though not exclusively) important positive outcomes. A certain amount of destruction of archaeological resources is not only unavoidable but can indeed be desirable in order to accommodate fairly as many genuine claims to ancient sites and objects as possible (cf. Vayne 2003). As extraordinary as this conclusion may sound, it should not be seen as jeopardizing the archaeological project at large. Instead, it offers a new opportunity for overcoming some of the established oppositions between archaeologists and other heritage “users,” such as collectors, developers, local communities, and other interested parties.

My main point in this chapter is that archaeological heritage management is and should be concerned with actively and responsibly renewing the past in our time. Instead of preserving too much in situ and endlessly accumulating finds and data for an unspecified future, it is more than appropriate to take seriously the challenge of providing experiences of the past that are actually best for our own society now (cf. Leone and Potter 1992). Archaeologists have the skills, experience, and responsibility to assist our society in constructing the pasts it desires—and deserves. As Tunbridge and Ashworth argue,

The production of heritage becomes a matter for deliberate goal-directed choice about what uses are made of the past for what contemporary purposes.... The recycling, renewal and recuperation of resources, increasingly important in the management of natural resources, can be paralleled in historic resources where objects including buildings can be moved, restored and even replicated.... The deliberate manipulation of created heritage can be a valuable instrument [in an efficient management of historic resources]. (1996: 9, 13)

When visiting a relic mound with a friend, anthropologist Steven Kemper (1991: 136) asked whether the place was ancient. “Yes,” the friend replied. “It was restored just last year.”