www.10.1

www.10.1Chapter 10

It were as wise to cast a violet into a crucible that you might discover the formal principle of its colour and odour, as seek to transfuse from one language into another the creations of a poet.

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, Defence of Poetry, 1821)

A major objective of applied linguists is to confront the kinds of problems (and embrace the opportunities) that arise when groups or individuals speaking different languages interact. Few people have communicative competence in more than two or three languages, at most, and yet there are perhaps as many as 7,000 languages still being spoken around the planet. Communication between speakers who don’t share a common language is a universal and – so far! – permanent problem faced by humanity, and thus falls within the scope of applied linguistics. One solution has been the adoption of a lingua franca (see, for example, Knapp and Meierkord, 2002). Mandarin Chinese, for example, has been established over the centuries by the rulers in Beijing as the national Putonghua (‘common tongue’) of China, enabling communication between mutually unintelligible linguistic groups in this vast country. Over the past few decades, European Union documents have increasingly been drafted in English (DGT, 2007a). But the other option is, of course, translation, and bilinguals have served as translators and interpreters since time immemorial. Indeed, in practice lingua franca usage often works hand in hand with translation. In the European Union, for example, a document written in Swedish is unlikely to be translated directly into Portuguese, but rather ‘relay-translated’ from Swedish to English and then from English to Portuguese. And in East Asia, English as a Lingua Franca is often the intermediary through which speakers of regional languages like Russian and Japanese understand each other (Proshina, 2005).

Although many practising translators and interpreters, as well as theorists who are specialists in the area of Translation Studies, may not in fact identify themselves as applied linguists, the root problem is clearly – and centrally – related to the concerns of the discipline. In this chapter we review the nature of the translation problem, in both linguistic and cultural terms, and sketch some of the ways in which language professionals from different traditions provide or propose solutions.

Translation Studies is the academic field concerned with the systematic study of the theory and practice of translation and interpreting. Research and teaching in the area are interdisciplinary, and closely aligned with Intercultural Studies (the largest professional organization is the International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies).

Before going any further, let’s identify and define some fundamental concepts. For example, the term translation refers to both a process and a product. The process is embedded within four communicative components:

Source language (SL) and target language (TL) are terms used in translation and interpreting to refer to the ‘translated-from’ and ‘translated-into’ languages, respectively. They are appealing terms because they implicitly assume a focus on interlinguistic meaning, and the process of moving from one language to another.

Translators are always responsible for at least two of the components (2 and 3). In some cases, however, a speaker/writer may translate his or her own text, so may be the agent in component 1 too. Samuel Becket originally wrote Waiting for Godot in French and only later translated it into his native English. Translators are always also constantly reading what they have written. Thus, Becket presumably read (component 2) the original text he wrote (component 1) before he wrote (component 3), and then read (component 4), the English translation.

How to define the products of translation is not so straightforward, and indeed how the TL text might or should correspond to the SL text and the original message will be a major topic in this chapter. One thing is certain: translation is almost never a mere TL recodification of a message originally expressed in the SL. We might claim that a particular word in one language has a translation equivalent in another language, such that English cat is equivalent to French chat. But a word is not the same thing as a message. For applied linguists, the translation problems of interest arise in actual communicative acts, where language is used on the basis of the underlying beliefs, intentions and interpretations of the various participants in the translation process. Translation is therefore not uniquely a process of linguistic substitution, but rather also a semantic, pragmatic and cultural process, in which ‘equivalence’ is elusive.

Translation equivalents are (often ideal or elusive) pairs of terms across languages which have the same meaning, to a greater or lesser degree. They may perhaps best be thought of as cross-linguistic synonyms.

In her memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran, the Iranian scholar Azar Nafisi (2003, p. 265) describes ‘[dancing to] music that was filled with stretches of naz and eshveh and kereshmeh, all words whose substitutes in English – coquettishness, teasing, flirtatiousness – seem not just poor but irrelevant’. If she is right, how would a translator render these Persian words into English? The example demonstrates that translation is inevitably a cultural object, by definition one which is the joint product of two or more different linguistic cultures. Translations are thus texts and discourses in and of themselves, the products not only of grammatical and lexical resources, but also of sociopragmatic processes and judgements. One consequence of this is that, as sociocultural acts and objects, translations will have sociopolitical ramifications, a theme we pick up throughout the chapter.

In this chapter we first look at some of the contexts in which translation happens (section 10.1), before discussing the various manifestations that translation processes and products take (10.2 and 10.3). We then focus in on the knowledge and skills needed by professionals in the field (10.4), before exploring the question of genres of translation and the interrelated issue of modality of expression (10.5 and 10.6). These sections allow us to ponder some of the sociopolitical questions surrounding the role of translation in the lives of disparate groups of language users. From human users we then turn to the rapidly expanding role of IT in translation (10.7). The chapter ends with a discussion of potential roles for graduates of applied linguistics programmes (10.8).

Translation is happening all the time, all over the planet, and has been since our earliest language-endowed forebears split into mutually unintelligible speech communities but stayed in contact for trade, war or mutual protection. In Mexico, the most famous of translators was La Malinche, the Indigenous interpreter for the Spanish conquistadors who conquered the region under Hernán Cortés (see Figure 10.1). She actually started out translating as the enslaved half of a relay-translation team, providing the linguistic bridge between the Maya spoken by Cortés’ original interpreter, Jeronimo de Aguilar, and Nahuatl, the main language of the Aztec empire.

Figure 10.1 La Malinche interpreting for Cortés in Xaltelolco (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

La Malinche is a powerfully iconic figure in Mexico, representing, on the one hand, the phenomenon of mestizaje, the dominant mixed-race (Indigenous and Spanish) ethnicity in the modern nation, as a source of rich social history and national identity; and, on the other hand, the enduring shame and anguish stemming from the original people’s perceived submissiveness. This duality is reflected in the two other names by which La Malinche was known: Doña Marina in Spanish and Malintzin in Nahuatl. La Malinche provides a powerful metaphor of the defining context of translation: as a meeting point not only of languages, but also of cultures, and very often of unequal partners.

La Malinche was not, of course, a professional or trained translator, although she is better remembered than many who were, as suggested by her inclusion in the Translator Interpreter Hall of Fame (Conner, n.d.). But then again much, probably most, translation, occurs outside the professional realm. In the many multilingual cities, towns and villages of the world (many of them lying beyond the native lands of the world’s regional and global powers), translation is a daily communication tool, more often than not oral. In India, over 400 languages are spoken, and in Papua New Guinea over 800. In Paraguay, Guarani is spoken by over 90 per cent of the population, but almost everyone in the capital uses it and Spanish in their daily lives. In South Africa, many people speak English as well as Xhosa, Zulu and other regional languages. In such multilingual communities (which, recall, are the rule rather than the exception), few members have access to all the languages they need, so translation is likely to be a very frequent occurrence.

Translation also happens in language classrooms all over the planet as an inevitable component of learning, sometimes under the guidance of the teacher, but probably more often involuntarily (Cook, 2010; see Chapter 9). Studies of language learners, especially those in the earlier stages of target language development, show that translation into the native tongue is an automatic, cognitive process, not susceptible to conscious control. Scholars who conduct research on vocabulary development in language learners have shown that the mind automatically forges memory connections between lexical entries which are perceived as translation equivalents (cf. Hall, 2002). Learners ‘translate’ into the L1, by activating perceived equivalents, whether they intend to or not! Recent research (for example Laufer and Girsai, 2008) also suggests that translation harnessed as a teaching tool can deliver significant benefits in vocabulary learning.

For linguists working to understand languages which are not well known outside the communities where they are spoken, translation is a fundamental tool, used to analyse the way the language works. In applied contexts, the knowledge derived from such translations provides evidence for linguistic recommendations regarding literacy education and language revitalization measures, or at least for the documentation and preservation of endangered languages and the cultures they express (see Chapter 5).

Here is an example from the US linguists Carolyn Mackay and Frank Trechsel’s volume on Misantla Totonac, a language spoken in the Mexican state of Veracruz (La Malinche’s homeland):

(1) ‘tuut lakáachu nalh taayaaní’ laawaní

que NEG-ya FUT aguanta-DAT 3OBJ.PL-dice.x-DAT

‘ese no lo va aguantar’ dice (él que era gavilán)

‘He’s not going to handle/bear/stand it’ says he (the one who was the sparrowhawk)

(Mackay and Trechsel, 2005, p. 96)

In their analysis of the story from which this tiny fragment is taken (which is about a sparrowhawk which changes places with a man), Mackay and Trechsel give four versions of the original spoken Totonac. First, in a practical orthography based on Spanish (the first line in our example), then phonetic and morphophonological transcriptions (not shown here), followed by a morphemic gloss (our third line: see the Leipzig Glossing Rules for a key) and, finally, a rendering in the Spanish dialect used in the region (not the national ‘standard’ variety). The last line is our translation of the Spanish. Now Mackay and Trechsel are native English-speaking general linguists rather than professional translators, and their informant is neither (although he is a bilingual Spanish–Totonac speaker). But their painstaking collaboration leads to a rich and informative descriptive analysis of Misantla Totonac, which, although designed to be used principally by linguists, is also made accessible to community members through practical orthography and the use of local Spanish varieties.

A morphemic gloss is an interlinear, morpheme-by-morpheme presentation in the reader’s language of the grammatical information and lexical meaning expressed in lines of text from another language.

Translation is being used by Mackay and Trechsel as a linguistic (and applied linguistic) resource. But most work in translation studies, most courses in translation training programmes and most of the day-to-day toil of practitioners is concerned with translation as communication: producing a text to make comprehensible its content, not its form. Perhaps the most visible professional translation products of this kind are written: novels and poems written originally in other tongues (Shelley’s caution notwithstanding); menus and hotel notices seen on vacation; search results from Google or Altavista’s Babel Fish. For those who live outside the mainly monolingual Anglophone nations, translations are encountered even more frequently, delivered through college textbooks, newspaper articles, consumer product instructions, sacred writings, international legal codes and a whole host of other imported texts. Spoken translations – the products of the interpreting process – are heard most widely through the TV, radio and film, although ever-larger numbers of globe-trotting conference attendees will hear simultaneous interpretations. Users of some sign languages will be especially familiar with the products of simultaneous interpretation (see section 10.5).

With the information technology revolution of the past few decades, professional translation has become a thriving service industry, worth over $9 billion annually in 2002, according to one report (ABI Research, 2002). But outside big international organizations like the UN and European Union (or internet giants and other multinational corporations), the most frequent context for the translation process is still that of the freelance worker, operating from home, either independently or through a small agency. Most translators join the profession because they happen to be or become bilingual and circumstances lead them to realize that their everyday bilingual competence is also a marketable skill. What applied linguistics can tell us about the development and effective deployment of this skill is our major concern here.

10.2 Translatability and Translation Equivalence

The original Latin word translatus (the past participle form of the verb transferre) meant ‘carried across’. Here, the translation process ‘carries across’ an intended message or meaning from one text to a second text in another language. Now when an object, let’s say a Mandarin–English bilingual dictionary of the sort discussed in Chapter 11, is carried from one place to another it is the same object, before and after carrying. But can we really say this about the meaning expressed by an SL text and its TL translation? Is translation a process which transforms linguistic expression but leaves meaning untouched? Such a view assumes ‘translation equivalence’, a belief in which underlies the efforts of most beginning language learners, but one which very soon becomes untenable if held too tightly. In his efforts to learn Latin and Greek, the English novelist Thomas Hardy’s character Jude, from Jude the Obscure, hoped for ‘a secret cipher, which, once known, would enable him, by merely applying it, to change at will all words of his own speech into those of the foreign one’ (Hardy, 1998 [1895], p. 30). The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset (1992 [1937], p. 109) likened this vain hope to the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, the process through which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed into the body and blood of Christ by the priest during mass: ‘Should we understand [translation] as a magic manipulation through which the work written in one language suddenly emerges in another language? If so, we are lost, because this transubstantiation is impossible.’

Although absolute equivalence at all levels is impossible, translated messages don’t necessarily suffer the drastic fate of Shelley’s violet in the crucible. Let’s see at what levels this ‘impossible’ process can happen. We noted on p. 224 that translation is simultaneously a linguistic, semantic, pragmatic and cultural process. To what extent can we expect a translation to approach equivalence to the SL text at these levels? We’ll take the linguistic level first. Clearly, phonological equivalence must normally be surrendered. The dual trick language uses to combine meaningless phonemes on one level and meaningful words on the other makes the achievement of phonological equivalence between source and translation impossible, except in the case of historical cognates or loan words (the concept ‘taxi’, for example, is expressed as something very close to /taksi/ in most – perhaps all – languages). This presents problems when the sound is important in the original, for example in poetry or punning. Let’s look at two examples of the latter.

Like many bilinguals living in a multilingual city, Chris became an accidental translator in Mexico City in the late 1980s (a clear case of native-speakerism; see Chapter 9). He was asked to translate into English a book on Mexican identity (Roger Bartra’s The Cage of Melancholy, 1992). In one section (p. 9), the author refers to the concept of postmodernity (posmodernidad), but remarks in a footnote that he prefers ‘the reverberations of the Spanish term desmodernidad ’. He goes on to observe that ‘[i]n English it might be termed “dismothernism”, but only Latin Americans would understand the desmadre implied in the translation’. This left the novice translator in a difficult position. The reader of the translation might not be familiar with the Spanish term desmadre, but understanding it is crucial for understanding the author’s own English pun. In the end, Chris added (rather lamely) ‘Translator’s note: desmadre (lit. “dismother”) means roughly “mess, ugly predicament”’.

Our second example is from English translations of The Satyricon, originally written by the Roman courtier Petronius (in Latin) a couple of millennia ago. At one point during a lavish feast, a servant boy is imitating the god Bacchus and the host, Trimalchio (a nouveau riche financier), makes a pun. In the original it is on the Latin word liber, which is both an alternative name for Bacchus and also the word for free. What should the translator do? In some early English versions, translators have faithfully explained the pun using parentheses. William Burnaby’s version (made three hundred years ago) renders the passage in clunky, almost impenetrable prose, as follows:

(2) ‘Dionysius,’ said he, ‘be thou Liber,’ (i.e.) free, (two other names of Bacchus)

… Trimalchio added, ‘You will not deny me but I have a father, Liber.’

(Petronius Arbiter, n.d.)

Frederic Rafael’s contemporary translation, on the other hand, uses only the name Bacchus, and makes the pun on that name:

(3) ‘Now you won’t question that I never lacked backers. Bacchus, geddit?’

(Petronius Arbiter, 2003, p. 52)

Readers will surely agree with us that this sly rendering, which maintains a pun (backers/Bacchus) but dispenses with the original phonology, is much funnier than Burnaby’s.

What these two examples show is that when a decision is made about equivalence on the lowest rung of our linguistic competence – i.e. that of form – it will have effects further up at the level of function. In the Bartra example, clarity was judged more important than mirth, so explanatory devices were used, but in The Satyricon , mirth is central to the writer’s intention and the reader’s expectation up to that point, so Rafael modifies semantic content to produce the appropriate literary sound effect.

At the lexical and grammatical levels, structural equivalence will rarely give you an authentic or effective TL version, since languages differ in the way meanings are mapped onto words, morphemes and syntactic structures. For example, the single Spanish word lustro must be rendered into English as two words in a syntactic relationship: NP[D[five] N[years]]; in contrast, many English compound nouns, like textbook, must be expressed in Spanish as nouns modified by prepositional phrases, like NP[N[libro PP[P[de] NP[N[texto]]]].

Different lexico-grammatical mappings can also lead to loss of equivalency at semantic and pragmatic levels. Again, take English and Spanish. The English pronoun you covers three different second person pronouns in Mexican Spanish: tú, usted and ustedes. The use of tú and usted reflects differences in intimacy and/or power relations with the addressee (a distinction common in other languages, such as the Indonesian kamu/anda). For example, usted is typically used with a stranger and tú with a child. The third form, ustedes, is used for more than one addressee and does not indicate level of formality. Thus, where an English SL text uses you the translator into Spanish must not only choose an appropriate lexico-grammatical form, but also make an appropriate sociopragmatic judgement not expressed in the original. Sometimes the original text will be ambiguous on purpose (when, for example, someone says, ‘I hope you can come to dinner’, and they really mean just one member of a couple because they can’t bear the partner but are too polite to say so).

The reverse case, where English must include semantic information that is not necessarily expressed in Spanish, is exemplified by the so-called ‘null subject’ phenomenon, whereby Spanish need not mention the subject of a verb but English must. And this can also have sociopolitical consequences: Spanish can ask (4B) about a university dean, a doctor or a government minister without indicating their gender, as the gloss on the second line shows. In English, on the other hand, one often uses either he/his or she/her in conversation (though they/their is increasingly common, even for singular subjects).

(4) A: Mi jefe despidió a diez personas ayer.

POSS-1P-SG boss fire-PAST-3P-SG to ten person-PL yesterday

My boss fired ten people yesterday

B: ¿Consultó a los miembros de su departamento?

consult-PAST-3P-SG to the-MASC-PL member-PL of POSS-3P-SG department

Did he/she consult the members of his/her department?

Translators run the risk of an accusation of sexism if they choose one gender over the other in English.

At the cultural level, equivalence will again, inevitably, be illusory, since cultures are defined by their differences, through time and space. We look again at translations of Petronius’ Satyricon. At a later stage of the banquet, the revellers are interrupted by the arrival of another of the host’s servants, who reads aloud from a report of the day’s affairs at one of his employer’s estates. In Alfred R. Allinson’s translation, the fragment goes as follows:

(5) … the historiographer, who read out solemnly, as if he were reciting the public records: ‘Seventh of Kalends of July (June 25th) … ’

(Petronius Arbiter, 1930, verse LIII)

This is problematic for modern readers, given the cultural distance between ancient Rome and contemporary Anglophone societies. Rafael’s solution is again to move from the original Latin and its linguistic equivalents and to use instead concepts from contemporary British culture. Thus, Rafael’s translation talks of

(6) … an accountant who came in and read out, as if from The Financial Times: ‘Twenty-sixth of July … ’

(Petronius Arbiter, 2003, p. 62)

Note the anachronisms: accountancy is a modern profession, the British newspaper was founded in 1888, and the date is given according to our Gregorian calendar, introduced in 1582. But the sentence says something to the modern reader that the more ‘equivalent’ versions do not.

10.3 The Translation Process

We claimed earlier that translation is happening all the time, throughout history and around the planet. We also claimed that this activity is not achieving the absolute equivalence between SL text and TL text envisaged in Jude the Obscure’s secret cipher or Ortega y Gasset’s transubstantiation. So what really happens in the translation process? What kind of translation products are possible? The unmagical process has been described as having three distinct stages (see, for example, Roberts, 2002, pp. 433–434). These stages connect together the four communicative components described at the beginning of the chapter (pp. 223–4) and may be summarized as follows:

comprehension of the original SL text, the end (product of which is a non-linguistic, conceptual representation in short-term memory);

comprehension of the original SL text, the end (product of which is a non-linguistic, conceptual representation in short-term memory);

expression of the comprehended message in the TL;

expression of the comprehended message in the TL;

revision of the TL text on the basis of a re-reading of the SL text and deeper consideration of the TL-speaking audience.

revision of the TL text on the basis of a re-reading of the SL text and deeper consideration of the TL-speaking audience.

Look at Figure 10.2, where the basic psycholinguistic process is diagrammed. It shows the essential flow of information and its transformation in the translation process. Outside the area defined by the dotted line, on the left, we have the original expresser’s message, the context in which it was formulated and the language in which it was encoded. This produces the actual physical manifestation of the linguistically encoded message: the SL text (which could be a poem, a novel, an instruction manual, a speech, a conversational turn signed in a sign language, etc.). The translator uses her linguistic knowledge of SL and her non-linguistic (contextual) knowledge and beliefs about the circumstances of the text’s creation to comprehend the text. Then, using her knowledge of the TL and her understanding of the contextual circumstances and cultural knowledge available to TL speakers, she encodes the comprehended message in the TL, thus producing the TL text. If we added a receiver to this diagram (the reader of the translated poem, the interlocutor in the conversation between British Sign Language and English speaker, etc.) we’d end up with three conceptualized messages. As our examples and arguments above have demonstrated, these three messages will not be identical.

Figure 10.2 The translation process

This is, of course, something of an idealization, since many translators (especially non-professional, non-balanced bilingual ones) will not wait for a full conceptual representation of the message to be built in the mind, and will read off translation equivalents at levels of processing which precede the final state of comprehension. An example is word-for-word translation (like the glosses used by descriptive linguists), which will often produce a very foreign-sounding – probably incoherent – TL text, with the word order of the SL and none of the meaning derivable from contextual cues. A subsequent level of translation, centred around the sentence or clause, will correspond to the propositional level of semantics: the literal, but not the pragmatically interpreted meaning. For the translation to be effective, it will need to take into account the whole gamut of linguistic, contextual, cultural and encyclopaedic information available. In order to achieve this, translators need to know, or come to know, an awful lot.

10.4 What do Translators Need to Know?

Professional translators clearly bring to their task a broad range of linguistic and applied linguistic knowledge, ideally including all of the following:

grammatical competence and fluency in the relevant TL variety(ies);

grammatical competence and fluency in the relevant TL variety(ies);

grammatical competence and fluency in the relevant SL variety(ies);

grammatical competence and fluency in the relevant SL variety(ies);

(access to) a large and varied vocabulary in both languages, including specialized terminology tied to often very narrow professional or cultural domains;

(access to) a large and varied vocabulary in both languages, including specialized terminology tied to often very narrow professional or cultural domains;

explicit metalinguistic knowledge about the grammars of both languages and about areas of grammatical overlap, alignment or disparity;

explicit metalinguistic knowledge about the grammars of both languages and about areas of grammatical overlap, alignment or disparity;

knowledge of the pragmatic routines through which SL and TL map communicative intention and effects onto linguistic expressions;

knowledge of the pragmatic routines through which SL and TL map communicative intention and effects onto linguistic expressions;

knowledge of a range of styles, genres, registers, dialects and international varieties associated with both languages;

knowledge of a range of styles, genres, registers, dialects and international varieties associated with both languages;

knowledge of literacy and the ability to read and to write (and speak or sign) clearly and elegantly (i.e. knowledge of the conventions of appropriate style for a range of contexts);

knowledge of literacy and the ability to read and to write (and speak or sign) clearly and elegantly (i.e. knowledge of the conventions of appropriate style for a range of contexts);

knowledge of translation theory and the range of professional resources and strategies that may be employed to translate effectively.

knowledge of translation theory and the range of professional resources and strategies that may be employed to translate effectively.

As we’ve seen repeatedly, much intended meaning goes unexpressed through linguistic form, being presupposed by SL expressers on the basis of shared context and locally or universally shared knowledge of the world and our social roles and practices within it. So translators must also bring to bear a considerable amount of non-linguistic knowledge, in order to understand the SL text, locate appropriate expressions in the TL and compensate for gaps in the TL receiver’s knowledge. Among other things, they’re likely to need:

knowledge of the cultural background of the expresser and of the knowledge the expresser assumes the SL receiver to have (the expresser is writing for speakers of the SL, not the TL, and so assumes knowledge which the TL receiver may not possess);

knowledge of the cultural background of the expresser and of the knowledge the expresser assumes the SL receiver to have (the expresser is writing for speakers of the SL, not the TL, and so assumes knowledge which the TL receiver may not possess);

knowledge of the subject matter of the SL text and the extent to which aspects of it are limited to the expresser’s cultural context;

knowledge of the subject matter of the SL text and the extent to which aspects of it are limited to the expresser’s cultural context;

knowledge of the social and political practices, and the moral and behavioural norms, of the expresser’s and receivers’ cultures;

knowledge of the social and political practices, and the moral and behavioural norms, of the expresser’s and receivers’ cultures;

‘research intelligence’: the skills required to find appropriate terminology and identify reliable sources (especially on the internet);

‘research intelligence’: the skills required to find appropriate terminology and identify reliable sources (especially on the internet);

a clear understanding of the specific needs of the client (both the commissioner of the translation and its end-users), as well as professional credibility and personal trustworthiness in the clients’ eyes (Edwards et al., 2006).

a clear understanding of the specific needs of the client (both the commissioner of the translation and its end-users), as well as professional credibility and personal trustworthiness in the clients’ eyes (Edwards et al., 2006).

These areas of knowledge must often also extend to earlier epochs, especially in the case of non-contemporary literature, historical documents, ancient inscriptions and the like. A famous example of the latter is that of the 2,200-year-old Rosetta Stone, a granite tablet found in el-Rashid (Rosetta) in Egypt in 1799, on which is inscribed a decree issued by the priests of Ptolemy V. The decree is written three times: in hieroglyphs, common (or demotic) Egyptian and Greek (see Figure 10.3). This gave scholars an opportunity to compare three versions (translations) of the same original message, and thus crack the hieroglyphic code, which had gone out of use and become forgotten some 1,400 years before. It took over two decades to interpret the inscriptions, and the final breakthrough was made by Jean-François Champollion early in the 1820s. If you take a look at the English translation on the British Museum website, you will appreciate how crucial it must have been for the translators to possess detailed knowledge of the political and social history of Ancient Egypt.

Figure 10.3 The Rosetta Stone (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The range of translation types is as broad as the range of discourse types. Just as discourse analysis (Chapter 4) distinguishes between genres on the basis of formal linguistic properties of texts and the social and communicative purposes to which they are put, one can classify translation tasks and products according to the linguistic and functional challenges they present to the translator. Technical translation is often treated as the poor relative in the family of translation types. For example, the index to Venuti’s (2004) anthology of seminal writing in translation studies includes only seven brief references to the topic, compared to over twenty more extensive ones to the translation of literature. Literary translation is certainly less constrained by the SL text, giving greater power of decision to the translator and providing almost unlimited scope for creativity, inventiveness and imagination. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (2004 [1935], p. 45) celebrates Mardrus’ ‘luxurious’ translation of The Thousand and One Nights, claiming that ‘it is his infidelity, his happy and creative infidelity, that must matter to us’. With technical translation, on the other hand, that licence must be sacrificed in favour of complete fidelity. The translator’s responsibility here is enormous: on his or her shoulders rests the well-being of patients taking foreign drugs, the proper functioning of machinery in factories and homes, the financial stability of companies and countries, the good health and effective training of workforces, the balance of justice in legal proceedings, and the outcomes of millions of other situations in which the mistranslation of a word or expression may have adverse effects.

Here’s one revealing example, which also nicely illustrates the importance of explicit metalinguistic knowledge and subject matter knowledge (cf. section 10.4). The website of the US-based technical translation service RIC International tells of a mistranslated motorcycle manual they had to put right:

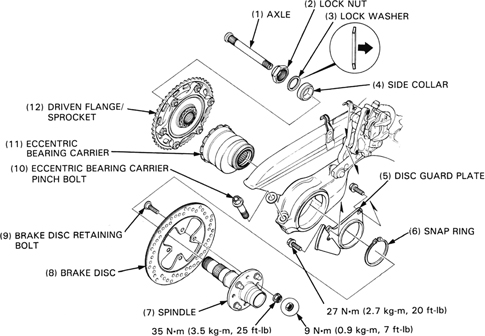

One of the more interesting errors, though far from being the most egregious, was in the translation of the original English instruction: ‘Loosen the eccentric bearing carrier pinch bolt.’ In the Italian version of the manual, the sentence was referring to an eccentric bearing; in the French manual, it was referring to the eccentric bearing carrier; and the Spanish translation referred to the eccentric pinch bolt!

(RIC International, n.d.)

For those unfamiliar with this use of the word eccentric (as we were until we looked it up), it means here ‘not concentric’ or ‘not placed centrally’ (the literal meaning of its ancestor in Greek) (see Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Loosening the eccentric bearing carrier pinch bolt

What’s special about this example is that it wasn’t just the technical vocabulary that led to the mistranslations, but also the linguistic analysis of modification relations between adjectives and compound nouns (structures which are very uncommon in the Romance languages). In order to understand the SL text and thus provide a faithful TL version, the translator must have (1) awareness of linguistic modification ambiguities (so-called ‘bracketing paradoxes’) and (2) the subject matter knowledge which will permit them to make the right choice between alternative interpretations. If they don’t, users of the resulting manual will end up rotating the wrong bit of the motorcycle, or be unable to locate the correct piece in the first place.

Technical and literary translation are often correlated with opposite poles on a continuum of translation types defined by their fidelity to the original language and culture of the SL or, put differently, whether they are text-focused or reader-focused. Different terms, reflecting different but overlapping parameters of fidelity, have been used to label the poles of the continuum. Table 10.1 lists some of the more commonly used terms and their focuses.

Table 10.1 Types of translation at the poles of a continuum defining greater focus on the text vs greater focus on the reader

| Reader-focused types (least faithful to SL) | Text-focused types (most faithful to SL) |

| Functional | Formal |

| The translation seeks to render the functions of the SL text, independently of its original linguistic form. | The translation seeks to render as close as possible the form of the SL text, which might sometimes require sacrificing aspects of its function. |

| Communicative | Semantic |

| The translation seeks to communicate the original expresser’s message, whether it enjoyed explicit linguistic expression in the SL text or not. | The translation seeks to render the literal meaning of the original text, leaving unexpressed any meaning which was only implicit in the original. |

| Text-based | Word-based |

| The translation process operates on the meaning of the whole text. | The translation process operates on the level of the sentence. |

| Shift | Equivalence |

| The translation modifies the content of the SL text in the interests of the reader’s — and translator’s — localized cultural knowledge and needs. | The translation does not contain any meaning which is not in the original. |

| Domesticating | Foreignizing |

| The translator adapts the translation to local conditions. | The translation maintains as many elements of the SL and source culture as possible, even when the result does not sound colloquial in the TL or familiar in the target culture. |

The formal–functional dichotomy (Nida, 2004 [1964]), for example, will be apparent in the translation of poetry, or any other literary text in which linguistic form (rhyme, metre, alliteration, etc.) may be an integral component of the poet’s intended effect. How should one render in Japanese, for example, Dylan Thomas’s (2006 [1954]) ‘play for voices’ Under Milk Wood, which contains expressions like ‘… the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea’? In other cases, the purpose of the translation may dictate the focus. A translation of an ancient text for the general reader may focus on function, but the same text intended for scholars may focus more on form, using extensive footnotes or parenthetical explanations to compensate for the semantic and cultural opacity that might result from the reader’s cultural and temporal displacement. The first type, then, the product of text-based translation, will be more communicative, resulting in shifts, whereas the second type, the product of word-based translation, will be more semantic, striving to maintain equivalence.

We have already seen a number of examples of these differences in focus. MacKay and Trechsel’s (2005) grammar of Misantla Totonac uses formal, semantic, word-for-word translation equivalences in the literal glosses intended for linguists seeking to understand the structure of the SL, but also more communicative translations into colloquial Spanish for members of the local Indigenous community. Over the centuries, the various translators of Satyricon have moved from a text-focused to a reader-focused orientation, as changes in society have accelerated, moral positions have become more relaxed and readerships have expanded far beyond the erudite elites. Certain kinds of texts, most often technical ones like the motorcycle manual retranslated by RIC International, are intended for universal application and so are inevitably text-based. Others are so tied to the cultural setting and epoch of their original creation that some translators have sought to make them more accessible by domesticating them. Rafael’s translation of Satyricon is again a good example. (Apart from the reference to the UK daily the Financial Times, he mentions two other non-Roman institutions – the United Nations and Mickey Mouse – elsewhere in the text.)

But domesticating a text is not only the semantic process of replacing outdated concepts with contemporary ones or local ones with foreign. At the discourse level, translators may also implement shifts of a higher order, which adapt an SL text to the predominant ideologies and moral attitudes of the TL readership. Perceived obscenity in the SL text, for example, can in certain epochs and cultures tempt translators to perpetuate drastic domesticating shifts in the translated text, in order to protect their local readers from moral outrage. Borges tells of Edward Lane’s nineteenth century translation of The Thousand and One Nights, describing it as ‘scrupulous’ (recall his use of ‘luxurious’ to describe Mardrus’ less inhibited version). But, he goes on, ‘[t]he most oblique and fleeting reference to carnal matters is enough to make Lane forget his honor in a profusion of convolutions and occutations’ (Borges, 2004 [1935], p. 36). Perhaps more honourable is the strategy taken by the translator of the words of Orff’s Catulli Carmina (the second work in the series which starts with Carmina Burana) in the 1954 Vox LP recording, part of which we faithfully reproduce in the following:

O tui oculi, ocelli lucidi, fulgurant, efferunt me velut specula |

O your brightly shining eyes, how they exalt me! O your charming, alluring lips! O your nimble tongue! |

O tua blandula, blanda, blandicula, tua labella ad ludum ad ludum prolectant |

For obvious reasons the translation of the following lines has been omitted. |

O tua lingula, usque prerniciter vibrans ut vipera (cave, cavete meam viperam nisi te mordet) |

|

Morde me, basia me. |

|

O tuae mammulae… |

The reasons for the absent translation may not be all that obvious to the reader who knows no Latin, but at least he or she is not misled!

Other translators have domesticated their products so that they serve purposes which may be different from those of the original expresser’s, such as missionaries who introduce concepts from local religions in order to mask conversion as continuity, or political activists who introduce local concepts which correspond to their own agenda. Venuti (2004, p. 471), however, draws attention to the fact that this kind of shift is often an inevitable consequence of freer translation, rather than being a conscious objective of the translator: ‘The foreign text is rewritten in domestic dialects and discourses, registers and styles, and this results in the production of textual effects that signify only in the history of the domestic language and culture.’ Ideological motives also often underlie the opposite stance, that of foreignizing the translation in order to make the non-local and/or non-contemporary characteristics of the SL text more transparent.

The process inevitably results in non-colloquial TL forms, but this is seen as an inevitable price to pay for conceptual fidelity. The exiled Russian novelist and translator Vladimir Nabokov (2004 [1955], p. 115), for example, proclaimed that ‘[t]he clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase’. He believed this, according to Venuti (2004, p. 68), because ‘[h]e nurtures a deep, nostalgic investment in the Russian language and in canonical works of Russian literature and disdains the homogenizing tendencies of American consumer culture’. A very different rationale has underlain the practice of Chinese literary translators since the 1980s, according to Xianbin (2007). He observes that Chinese translators tend to foreignize their translations from English into Chinese and to domesticize their translations from Chinese into English, which he explains as an effect of the respect which globally dominant English now has in China, so that Chinese texts will be made as accessible as possible to English speakers, but English texts will be tampered with as little as possible when rendered in Chinese.

Finally, from a postmodern, feminist perspective, Spivak (2004 [1992]) argues that many (especially English) translations of postcolonial literature fail to reflect an ‘intimacy’ with the rhetorical context of the original, resulting in the use of bland Western ‘translatese’. As an example, she mentions the Bengali novelist Mahasweta Devi’s Stanadãyini, translated as The Wet-nurse in one version, but in another as the more faithful, but less neutral, Breast-giver. The first comfortably domesticates, the second uncomfortably foreignizes.

10.6 Interpreting and Audiovisual Translation

So far in this chapter we have concentrated on translation as a deliberate, reflective process, displaced in time and space from the creation of the original SL text. This is due fundamentally to the success story of literacy (see Chapter 6): writing leaves permanent records, both of SL texts that may be translated multiple times and of translated texts that may be studied and critically discussed again and again. The modalities of speech and sign, on the other hand, leave transitory footprints which are more likely to be local in significance, are normally accessible only to those in the immediate vicinity and are thus less available to critical analysis.

But professional interpreting of oral and signed SL discourse is becoming an increasingly common and important aspect of global translation activity. We see three main reasons for this. One is that international travel has become so much cheaper and easier, resulting in more frequent and more varied multilingual encounters: for business people, professionals, academics, politicians, NGOs, special interest groups, artists, students on holiday and others. A second reason is the growth in transnational migration, also involving increased mobility but often motivated by economic needs or personal security rather than choice. A third and related reason is the growing recognition in many countries that residents who do not have access to one of the languages in which public affairs are typically conducted nevertheless have the right to participate fully in the affairs of their local and national communities. This is especially the case for linguistic minority groups such as Indigenous communities, immigrants and deaf people, so community interpreting is increasingly taught in training programmes and researched in translation studies departments.

Interpreting is the process of translating from and into spoken or signed language.

Community interpreting is interpreting for residents of a multilingual community rather than between members of different language communities: in doctor–patient encounters, job interviews or court proceedings, as opposed to international conferences and diplomatic or commercial meetings.

It is now common to see professional interpreters in schools, courtrooms, hospitals and countless other public domains, including TV and the theatre. Interpreting is an extremely complex and cognitively taxing skill, given its inherent temporal constraints. This goes for both simultaneous/whispered and consecutive interpreting. In the former cases, the interpreter must perform the psycholinguistic task diagrammed in Figure 10.2 in real time, without the luxury of preparing multiple drafts and consulting dictionaries. For this reason, in university classrooms, conferences and increasingly also in courtrooms, teams of interpreters are employed, working for thirty-minute stints. Given increasing globalization, relay-interpreting is becoming common, with English (or occasionally French) as the lingua franca. In the UN at Geneva, for example, Arabic- and Chinese-speaking interpreters will translate from and into English or French, the UN’s two working languages, and German-speaking interpreters will render original Chinese or Arabic content through the English or French versions (UNOG, n.d.). In consecutive interpreting, other challenges present themselves, especially the need in some contexts to accurately store lengthy fragments of the accumulating SL discourse in working memory, so that nothing is lost or substantially modified in the subsequent TL product. In this case, note-taking skills can be extremely important.

It’s simultaneous when the speaker or signer doesn’t pause for the interpreter to translate what they’ve expressed, for example when making an address at a conference (in a private meeting the translation may be whispered, also known as chuchotage). Interpreting is consecutive when the speaker/signer produces a stretch of discourse and then pauses while the interpreter translates it, and alternating phases of SL and TL ensue until the whole message is interpreted.

In both types of interpreting there is also an important ethical dimension, which does not present itself so frequently in written translation; this is because the spoken or signed SL discourse is often spontaneous (or at least not fully prepared or revised in advance), resulting in slips of the tongue or hand and apparent redundancies or inconsistencies in content, all of which are frequent distinguishing features of real-time discourse. Does the interpreter faithfully reproduce such mistakes, even if they are pretty sure they were unintended and they have a good guess at what was really meant? Ethical guidelines from the US Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) suggest that they shouldn’t, recommending in their Code of Professional Conduct that interpreters ‘[r]ender the message faithfully by conveying the content and spirit of what is being communicated, using language most readily understood by consumers, and correcting errors discreetly and expeditiously ’ (NAD-RID, 2005, p. 3; emphasis ours).

In community interpreting the ethical issues go way beyond error-correction. Using the example of medical discourse, Sandra Beatriz Hale (2007) describes the long-standing debate in the field between the view of interpreters as brokers or mediators who may consciously modify, omit or add elements of the message, and the view taken by Hale herself, that a more direct ‘invisible’ approach is safer, given the high stakes of the discourse and the difference in status between the doctor and interpreter, on one hand, and the patient, on the other. When the interpreter takes an active role, crucial information may be lost or distorted, as the following example (with the Russian SL here rendered in TL italics) illustrates:

Doctor: |

Ah, are you uh having a problem with uh chest pain? |

Interpreter: |

Do you have a chest pain? |

Patient: |

Well how should I put it, who knows? It … sometimes it does happen. |

Interpreter (to patient): |

Once a week? Once every two weeks? |

Patient: |

No, this thing happens then depending on … on circumstances of life. |

Interpreter (to patient): |

Well at this particular moment do your life circumstances cause you pain once a week, or more often? |

Patient: |

Sometimes more often, sometimes more often. |

Interpreter (to doctor): |

Once or twice a week maybe. |

(Bolden, 2000, pp. 396–397, cited in Hale, 2007, p. 55)

Hale points out how important it is for interpreters to understand the crucial role of the doctor’s linguistic skills, especially in questioning, in order to make a full and informed diagnosis. In the example given here, the interpreter effectively deprives the doctor of his tools, and misrepresents the client.

As we saw in Chapter 6, ethnic minority children often serve as ‘language brokers’, informal translators and interpreters in communications between their parents and older relatives and representatives of the dominant culture (teachers at school, doctors, landlords, immigration lawyers and others). Although they are not paid for their services, the products of these translations can have important economic and legal consequences for the young interpreters and their families (Orellana et al., 2003). This phenomenon, in which bilingual children draw on their linguistic and pragmatic knowledge, also raises the ethical question of whether it is wise to have children play this role in matters that could cause them emotional harm (as might be caused by having to relay a doctor’s message to a sick parent), and to what extent it is the obligation of the state or government to provide translation services so that children are protected. A similar situation often holds for deaf people too, where relatives or friends serve as interpreters because professional interpreters are unavailable or too costly. Smeijers and Pfau (2009) report, for example, that most deaf users of Sign Language of the Netherlands (Nederlandse Gebarentaal, NGT) don’t book a state-funded interpreter for medical consultations because there are few available at short notice and yet appointments must be made on the day of the consultation. They suggest (Smeijers and Pfau, 2009, p. 10) that more resources might be available if NGT were to be granted ‘official language’ status.

Another ethical issue relates to the confidentiality of the information contained in the interpreted message. This arises from the fact that real-time language use is more often conducted in the private sphere than is the case with writing, which tends to have more public currency. Maintaining confidentiality is especially relevant for language minority members requiring interpreting at school (for example regarding academic performance), in consultation with medical professionals, and particularly so in legal proceedings. In the latter case, it is not uncommon for interpreters to be subpoenaed and called to give evidence in court about what someone has allegedly said or signed (Mathers, 2002).

There are also purely linguistic challenges for interpreters which are not shared to the same extent by translators. For example, German syntax places main verbs at the end of the sentence, requiring interpreters to wait or anticipate. And in typologically similar languages or a language with many loan words, cognates will get activated in the interpreter’s mind faster than perhaps more accurate translation equivalents (the ‘false friend’ problem familiar to additional language teachers). In both cases language structure combined with time pressure can lead to loss of translation quality. In the case of some sign languages and less common languages which lack codified standards and extensive lexicons (see Chapter 5) there may not be a ready term in the TL, resulting in loss of specificity or extensive circumlocution, both of which will place cognitive strains on the interpreter and so potentially compromise the quality of subsequent performance. Curiously, interpreting between sign and speech may be slightly easier than between two spoken languages, given the fact that in the former case comprehension and production are not competing for the same phonological system (one is vocal-acoustic, the other is manual-visual). We are not aware of any research on this; however, the fact that sign interpreters regularly work for longer than the thirty-minute cross-modal interpreting stint is suggestive.

Speech-to-sign interpreting is not the only cross-modal translation process, of course. In the sub-field of audiovisual translation, SL discourse in one or more modalities is rendered into corresponding or different modalities in the TL. The main context for this is the screen (TV, movie, computer, game console, mobile phone, etc.), hence the alternative name screen translation, and the typical process involved is subtitling, with dubbing (and non-lip synchronized voice-over) being other options. Subtitling is the dominant method because it’s cheaper than dubbing and doesn’t interfere with the original product. The downside, however, is that the TL version has to be considerably abridged from the original SL message, because the viewer needs time to both read the text and experience the sight and sound of the main attraction (this loss of information can be as much as 70 per cent, according to Chiaro, 2009, p. 148). Dubbing, which can retain much more of the SL message, is the preferred practice in a small number of countries and regions where official language pride is important, either in the context of major world languages vying with English (e.g. in China, Japan, Latin America and the French-, Italian-, German- and Spanish-speaking nations of Europe) or in the context of regional minority languages seeking greater presence in society (e.g. Catalonia, the Basque Country and Wales).

Audiovisual translation encompasses all translation involving multiple modalities (including multimedia), but typically involves subtitling or dubbing for screen-based language in film, TV and video games.

Subtitling is expanding, even in traditionally dubbing countries, especially for movies, where there is high demand for a fast release of Hollywood products after their US premiere. Despite the high demand for translation of screen products, quality is often compromised in the rush to release and the lack of involvement of translators in the production process. An interesting exception here is, however, video games, which represent a massive global market. Chiaro (2009, pp. 153–154) reports that, at least in the Japanese sector of the market, translators are involved from the outset and are given considerable freedom to adapt and modify SL text and speech so that it has maximum entertainment value for TL users (to the extent that the process is often called transcreation instead of translation).

The worldwide spread of English and US dominance of the film and TV industries means that people the world over are reading a lot of English subtitles. This can make translation a very effective teaching tool for additional language education (as we noted in Chapter 9), but it also has profound cultural and political effects, effectively disseminating the Englishes and cultures of Kachru’s ‘Inner Circle’ around the globe at the expense of local languages and local content. The translation theorist Henrik Gottlieb points out how TV companies in non-English speaking countries are trapped by economics here:

Today, American, British and Australian imports are so much more affordable to TV stations than domestic productions – as long as these remain difficult to export because neighboring countries keep filling their shelves with anglo-phone imports. Vicious or not, this circle needs to be broken, at least for the sake of linguistic and cultural diversity.

(Gottlieb, 2004, p. 89)

Dubbing is the standard practice for imported children’s films and programmes around the world, so at least the onslaught of English is delayed, even if the rest of the ‘polysemiotic’ code is going to reinforce Anglo-Saxon cultural hegemony. And at least with subtitling the translation is automatically ‘foreignizing’ in effect, if not in form: by presenting the TL at the same time as the SL whilst at the same time detaching the two through shifting the modality, subtitles interfere with the screen illusion, despite their familiarity in much of the non-Anglophone world.

10.7 Technology in Translation

Communication with extraterrestrials has never presented much of a problem in the science fiction canon. Fans of the genre know that many authors and screen writers have eliminated the intergalactic communication gap by conveniently assuming that all aliens speak fluent English! In more sophisticated treatments, it is almost universally assumed that technological advances will sooner or later result in the design of a gadget which will automatically translate between all galactic language combinations. Unless the Babel fish is discovered first:

‘The Babel fish,’ said the Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy quietly, ‘is small, yellow and leech-like, and probably the oddest thing in the Universe. It feeds on brainwave energy received not from its own carrier but from those around it. It absorbs all unconscious mental frequencies from this brainwave energy to nourish itself with. It then secretes into the mind of its carrier a telepathic matrix formed by combining the conscious thought frequencies with nerve signals picked up from the speech centres of the brain which has supplied them. The practical upshot of all this is that if you stick a Babel fish in your ear you can instantly understand anything said to you in any form of language. The speech patterns you actually hear decode the brainwave matrix which has been fed into your mind by your Babel fish.

(Adams, 1979, pp. 49–50)

The Babel fish is, of course, a fanciful notion, the product of the wild imagination of British author and humourist Douglas Adams, creator of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. But surely technology can succeed where biological evolution will – in this case – undoubtedly fail. Automatic translation has steadily progressed since its beginnings half a century ago. Many users of the internet will be aware of online tools like Google Translate or Altavista’s appropriately named Babel Fish. Both are powered by SYSTRAN, one of the major commercial developers of machine translation, whose products represent the state of the art.

Automatic translation (also known as machine translation, MT) is the study and practice of translation via computer software (now increasingly embedded in online applications on the internet). Like additional language teaching (Chapter 9), the MT enterprise is often characterized by its lack of success, but actually it’s only unsuccessful to the extent that it can simulate human ability, and this is an impossible yardstick when you consider the extent to which real language use depends on non-linguistic context.

But how close does the software get to actually performing like Adams’ original Babel fish or a skilled human translator? As an example, we fed the last line of the Hitch Hiker’s Guide quotation (‘The speech patterns you actually hear decode the brainwave matrix which has been fed into your mind by your Babel fish’) into the Altavista system and it gave us the following Spanish TL text:

(7) El discurso le modeló oye realmente para descifrar la matriz del brainwave que ha sido alimentada en su mente por sus pescados de Babel.

In order to test the quality of this translation, we then asked a balanced bilingual scholar of the Spanish language, and Altavista’s Google Fish itself, to back-translate the Spanish TL text into English. The results were (8) and (9) respectively:

(8) The discourse shaped him listens really to decipher the matrix of the brainwave that has been fed in his mind by his fish of Babel.

(9) The speech modelled really hears to decipher the matrix to him of brainwave that has been fed in its mind by its fish of Babel.

Back-translation is a way of assessing translation quality. You take a translation from Language A to Language B and obtain an independent translation back into Language A. The degree of discrepancy between the SL text of the first translation and the TL text of the second allows you to assess the quality of the original TL text. It’s basically the game known variously as Chinese Whispers, (Broken) Telephone, Arab Phone or Stille Post, but with alternating languages.

The back-translations in (8) and (9) reveal some major problems with the output in (7), most of them the result of the software’s lack of linguistic knowledge and insensitivity to context. For example, the erroneous use of the word discurso comes from the ambiguity of the original English word speech (meaning both ‘spoken language’ and ‘public address’) and the system’s inability to disambiguate it. Human translators would be sensitive to the subsequent verb hear (used more with the first reading than the second) and the context of the preceding text. The garbage in the first part of the sentence reflects the complex subordination rules used in the original, and brainwave remained untranslated presumably because it wasn’t there in the translation corpus.

This is a symptom of a larger difficulty in handling language faced by artificial intelligence (AI), the interdisciplinary field which designs machine-based intelligent systems. The fact that human languages use such complex bio-computational systems, coupled with the fact that they may be used to communicate an infinite range of messages which are almost always interpretable only when combined with vast sources of non-linguistic knowledge, makes the complete simulation of any one of them by a computer well nigh impossible, at least for the foreseeable future. And if this is the case, you can imagine the extent of the challenge presented by machine translation programmes, which require knowledge of more than one language and more than one set of cultural and contextual knowledge.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the interdisciplinary field which develops theory on, and designs and tests, machine-based intelligent systems, like those telephone helpline systems that (fail to) understand your spoken instructions. We don’t recommend the Spielberg movie of the same name.

As a result, although machine translation software may be relied upon by end-users when all that is needed is a rough-and-ready sketch of the meaning of the original SL text, it is normally only used professionally as a support tool. For example, the European Commission makes available its own version of SYSTRAN software as an IT aid for staff who need to quickly browse or draft documents in a language they do not speak. But when it is used by the Commission’s translation service, the output must be extensively edited by hand (DGT, 2007b, p. 11), requiring knowledge of the SL text.

Recent developments in linguistics and computer science, however, suggest that the Babel fish ideal may be swimming closer, even if it will probably never actually arrive. The ‘father of modern linguistics’ Noam Chomsky has always stressed that human language is a system with infinite expressive potential obtain-able through (1) a finite set of grammatical rules and (2) a finite lexicon. Modelling the lexicon is not the toughest nut to crack for AI, given modern computers’ enormous memory capacity and the growing tendency to create programmes which mimic the massive interconnectedness of neural networks. Ignorance of a term (like brainwave in our Babel Fish example) is easy to put right: you just add an entry to the lexicon. There are now extremely large specialized terminology banks and multilingual dictionaries available for different subject areas, many available online. And through interconnected lexical entries you can simulate context effects by, for example, making stronger connections between hear and ‘speech as spoken language’ and between listen to and ‘speech as public address.’

Terminology banks provide searchable bilingual or multilingual glossaries of technical or specialist vocabulary for use by translators. A good example is the government of Quebec’s Grand dictionnaire terminologique in French, English and Latin. Another is Nuclear Threat Initiative’s Chinese– English glossary of arms control and nonproliferation terms.

It is the unfathomable complexity of grammatical rule-systems that has stymied AI language projects in the past (and currently available machine translation systems, as we saw with the subordinate clauses of our Babel Fish sentence). But what if the ‘easy’ lexicon could be souped up and the ‘difficult’ rule-system made redundant? Non-Chomskyan linguists have recently begun to propose that the central role of the rule-system in human language has been exaggerated, and that in fact much of language behaviour may be accounted for by the production and comprehension of memorized chunks: precisely what the lexicon is good for.

There are now massive computational databases of already-used bits of language, namely the language corpora that we explored in Chapter 9. So a new approach to machine translation exploits these resources in the form of alignment between attested fragments of discourse and their known equivalents in other languages. This is a modern-day version of what Champollion did with the Rosetta Stone: recall that he used the three aligned inscriptions on the stone to interpret (translate) hitherto undeciphered hieroglyphic texts. Statistical translation does the same with SL texts by searching for the statistically most probable matches in a translation corpus, – say, the combined database of translated documents at the United Nations. The advantage over earlier translation programmes which sought to simulate human rule-governed language processing is evident. For one thing, the output will be real, human, translator-produced language, rather than pseudo-language generated by machines. For another, such systems will be able to translate vast quantities of documents incredibly rapidly, without compromising inter-document consistency of terminology and style (a perennial problem when human translators work as a team on longer texts). Given the size, scope and impact of the internet, there’s a lot more information out there now which needs to be translated. The linguist Richard Sproat (2010, p. 241) concludes his discussion of these developments with the following observation: ‘the gap in quality between machine translation and human translation has narrowed. But equally importantly, the information needs of the world have changed.’

Statistical translation (or probabilistic translation) is a procedure which identifies already-existing translations of chunks of texts and yields the most likely match. An example is Google Translate, which uses millions of pages of translation from the United Nations.

A translation corpus is a computerized database of existing pairs of SL and TL text fragments in phrase-, sentence-and paragraph-sized chunks, for use in translation software, also known as a translation memory.

But by turning their backs on Chomsky’s insight regarding the infinite expressivity of language, the developers and promoters of statistical translation leave no options for the automatic translation of novel material. As Kirsten Malmkjaer puts it:

Language use must … be deferential to future users, and although past usage constitutes a monumental corpus that guides and informs future usage, it can neither determine nor reflect future usage. Seen in this light, translating is a display of creativeness.

(Malmkjaer, 2005, p. 185)

The point here is that automatic statistical translation will never replace the human translator, since a great deal of language output is both novel and unpredictable.

By this we don’t, of course, mean to suggest that stored, aligned translation fragments will not be a useful tool to translators: on the contrary, they have already eliminated much of the drudgery and redundancy implicit in technical and non-literary translation. At the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Translation, for example, their Euramis suite of translation tools includes a huge database of more than 88 million ‘translation units’ in all of the European Union’s twenty official languages (DGT, 2007b, p. 9). At the human translator’s request, the software can simultaneously display both identical and ‘fuzzy’ matches from this huge translation memory, together with SYSTRAN’s machine translation output. Figure 10.5 gives an example of Euramis in action. The lower pane shows the ongoing translation (from Dutch to French), and in the upper pane you can see the SL fragment sent for matching to the translation memory, and below it the matched SL and TL pair retrieved.

Figure 10.5 Example from Euramis of combined retrieval from translation memory and machine translation (Source: DGT, 2007b, p. 22)

Some freelance translators use Euramis, and it has transformed their work, while others may be much happier reaching for their battered bilingual dictionaries or consulting peers online (e.g. in one of the forums at WordReference.com); as we saw in Chapter 5, an overly ‘mechanistic’ approach to translation in the EU has been accused of constituting a threat to quality (Tosi, 2006). But whatever the reaction by individual translators, the role of IT is set to grow enormously over the next decades. Although Ortega y Gasset’s concept of magical transubstantiation, Hardy’s secret cipher and Adams’ Babel fish will remain forever elusive, all three writers would be truly amazed at how close technology is getting to achieving their impossible dreams.

10.8 Roles for Applied Linguists

The many ‘accidental translators’ who take on translation projects because they are bilingual or have a high proficiency in another language are often surprised by the challenges that translation poses, and are unprepared for the subtle judgements and breadth of linguistic and non-linguistic knowledge that the process requires in order to deliver a high quality product. But their prevalence in the industry is often aided and abetted by clients, for two main reasons: accidental translators normally charge much less for their products than trained professionals and in many cases clients cannot evaluate the product because they lack proficiency in the TL.

The discipline of applied linguistics can play a major role in the professionalization of the industry as a whole and of individual members working within it, even though many practitioners and even academics in the area may not recognize this (e.g. Townsley, 2007). Look once more, for example, at the list of knowledge areas sketched in section 10.4. The kind of sensitivity to linguistic and cultural factors represented in these areas, together with the ability to use them in a practice which directly involves clients and other agents who are unversed in linguistics, is precisely the balanced, integrated view that applied linguistics is good at focusing. Thus, a thorough grounding in applied linguistics is excellent preparation for professional accreditation as a translator or an interpreter, or for enrolment in a Translation Studies postgraduate programme which focuses on specific methods, techniques, strategies and resources.

Translation studies programmes in the universities are normally at the master’s degree level and are offered in different academic contexts, most commonly: (1) in association with comparative literature or literary studies; (2) in foreign language departments; (3) with linguistics or applied linguistics; or (4) as separate entities, often in combination with intercultural studies. Undergraduate applied linguistics degree programmes will sometimes offer courses in translation studies, but even when they don’t, such a degree will provide the sensitivity to language in its cognitive and sociocultural contexts that translators and interpreters must possess.

Applied linguists must also play a role from outside the profession, sensitizing both translators and their clients to a range of applied linguistic issues, such as:

the urgent need for translated materials into and from minority languages, especially Indigenous languages that are in danger of disappearing;

the urgent need for translated materials into and from minority languages, especially Indigenous languages that are in danger of disappearing;

the need to educate politicians and policy-makers about the linguistic rights of citizens and non-citizens, who may, in order to exercise these rights, require interpreting and/or translation services they can easily access, and trust;

the need to educate politicians and policy-makers about the linguistic rights of citizens and non-citizens, who may, in order to exercise these rights, require interpreting and/or translation services they can easily access, and trust;

the need to carefully consider educational materials such as curriculums and tests which have been translated from one language to another but which are not culturally relevant to target users;

the need to carefully consider educational materials such as curriculums and tests which have been translated from one language to another but which are not culturally relevant to target users;

the need to point out the necessary, and useful, role that translation processes and products play in additional language learning;

the need to point out the necessary, and useful, role that translation processes and products play in additional language learning;

the need to inform educators and other public speakers who work with deaf learners and audiences to provide visual and pragmatic cues that will simplify the job of sign interpreters (e.g. face the audience, stay in one place, speak more slowly, etc.).

the need to inform educators and other public speakers who work with deaf learners and audiences to provide visual and pragmatic cues that will simplify the job of sign interpreters (e.g. face the audience, stay in one place, speak more slowly, etc.).

For Shelley’s violet to survive the crucible, applied linguists certainly have their work cut out. But they have a much better chance of successfully meeting the practical challenges of translation than those who assume that bilingualism is all you need.

(a) providing classes in the majority language (for people who either are not able to use the majority language at all or only have a very basic level of proficiency);

(b) providing classes in a range of minority languages (for people who either are not able to use the minority language offered at all or only have a very basic level of proficiency);

(c) translating local government documents into minority languages;

(d) providing interpreters who can translate between the majority and minority languages.

What questions would you need to ask the mayor before starting to formulate your advice?

3 The mayor asks you to join an interview panel for the post of translator/ interpreter. What are the linguistic, social and personal skills necessary for the job? Make a list of six interview questions that will help you judge who is the best candidate for the job.