national language academies to establish, standardize and compel adherence to policies on terminology and orthography;

national language academies to establish, standardize and compel adherence to policies on terminology and orthography;Chapter 5

The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft a-gley,*

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promised joy.

(Robert Burns, To a Mouse, on Turning Her Up in Her Nest, with a Plough)

(*often go awry)

In Chapter 4 we explored discourse analysis as a tool that applied linguists use to understand how speakers, signers and writers employ language to represent themselves and others in given contexts. In this chapter we focus on the area of applied linguistics known as language policy and planning, defined by Robert Cooper (1989, p. 45) as ‘deliberate attempts to influence the behaviour of others with respect to the acquisition, structure, or functional allocation of their language “code”’. Thus, language planners are concerned with decisions about language use by, and on behalf of, a wide range of clients of applied linguistics. Like the students and practitioners whose concerns we’ve discussed in the rest of Part A, language planners and policy-makers are concerned with aspects of language in everyday use, and in understanding and solving a broad range of contemporary problems in which language is sometimes the target or end and sometimes the means or tool by which other (non-linguistic) issues can be resolved. An example of the former is the government of China’s decree that Mandarin Chinese be the obligatory language of schooling across the nation:

Article 10 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Use of Language and Script … ordains that all schools and other educational institutions in China must adopt Mandarin and standard Chinese written characters as their primary teaching language and written form.

(Chen, n.d.)

Language planning aimed at language as an end includes also the work of:

Orthographies are symbolic systems for representing language in visual form (or tactile form, in the case of Braille). They can include alphabetic and syllabic elements, and are the focus of applied linguists working with literacy development in written and previously unwritten languages.

national language academies to establish, standardize and compel adherence to policies on terminology and orthography;

national language academies to establish, standardize and compel adherence to policies on terminology and orthography;

lexicographers to provide a useful record of common usage of words;

lexicographers to provide a useful record of common usage of words;

applied linguists who devise orthographies for previously unwritten languages.

applied linguists who devise orthographies for previously unwritten languages.

Echoing the concern of the last two chapters to distinguish between language as end and language as means, we recognize here that planners and policy-makers at various levels seek to solve problems in which language is not the ultimate goal or target, but is a key variable or factor in some other social issue. A great deal of official language planning, for example, aims to provide citizens and clients with access to opportunities to participate in public institutions, and to receive services in legal, medical, work and religious domains. And at the individual level, a well-meaning parent or teacher might discourage a child from speaking the local language, promoting instead a more dominant or prestigious language or variety, not from a wish to influence the use of a particular language, but from a desire to shape the child’s social aspirations, educational attainment and economic well-being.

Language policy and planning involve decisions made by individuals (about their own language use and often about the language use of others), as well as decisions made by and for members of certain groups. In this, it is similar to additional language education (Chapter 9) and literacy (Chapter 6), because non-specialists often take leading roles in decision-making processes. Indeed, as we’ll see in numerous cases, the disciplinary knowledge and expertise of applied linguists are very often only one factor to be considered in complex problems. For this reason, some scholars have categorized language planning as a ‘wicked problem’ (Ricento and Hornberger, 1996) – one which, due to its complexity, may be inherently unsolvable, at least from the vantage point of current scholarly and professional knowledge. Throughout this chapter, we bear in mind that the success and effectiveness of language policy and planning efforts will depend on the ability of applied linguists to collaborate with other stakeholders, and (to tamper with Burns’ epigraph) that the best laid schemes of applied linguists gang aft a-gley for reasons that are not linguistic. Our intention is to map the current state of language planning as an area of applied linguistics practice, giving due consideration to the diverse and interrelated social, economic, linguistic and environmental issues that are involved.

We begin the chapter in section 5.1 by describing language decisions, distinguishing between those which are aimed at language as an end and those in which language figures as a tool or means to other (non-linguistic) ends. We go on to consider the work of language decision-makers and the question of who decides what, for whom, in whose interests, and then end the section with a discussion of the work of professional and scholarly language planners and policy-makers. In 5.2 we take up the formal categories of corpus planning, status planning and acquisition planning. In 5.3 we look at issues involved in efforts to keep languages alive – language vitality, language maintenance and language revitalization – as well as considering the aspects of planning and policy in which language is a tool rather than a goal. section 5.4 outlines language policy and planning for access to services in domains such as education, health care, the law and the workplace. section 5.5 considers two key aspects of language policy and globalization: language and poverty and language and immigration, using linguistic landscapes as a tool for mapping this corner of the field of applied linguistics. We conclude (5.6) with a discussion of roles for applied linguists.

All people make numerous decisions involving language use in their daily lives. As we saw in Chapter 1, however, much of our use of everyday language takes place so quickly as to seem instantaneous, meaning that many choices about how we use language are not made consciously and are, therefore, not really decisions at all. Choice in this sense is probably more accurately thought of as processing, since the real-time constraints of language in use do not lend themselves to the type of policy and planning we are concerned with in this chapter. Other decisions, such as which words convey just the right shade of meaning in an apology or a request, the most appropriate register or form of address when talking with a respected elder, or a sign interpreter translating English into British Sign Language during a university lecture, are more available to conscious reflection, but constant attention and attempts to control them too closely would be inefficient and would soon impede communication. Fortunately, as we outlined in Chapter 4, members of speech communities share linguistically enacted cultural routines – the stuff of pragmatics – that allow us to perform effectively most of the time without having to devote too much attention to language form.

Other kinds of decision involve deliberate choices, based on awareness, even monitoring, of language practices in a given situation. Grima’s (2005) guidelines for developing school language policy, for example, include a checklist for recording the language(s) children and teachers use with different interlocutors and for different purposes as they interact in a bilingual classroom (Table 5.1). Notice the choices include either of two languages of instruction and a third option, code-switching between languages.

Table 5.1 Pupil interaction table (Source: adapted from Grima, 2005)

Language Decision-Makers

In this chapter, we take the position that everyone is a language decision-maker in that we all make decisions about our personal use of language. These decisions can influence the ways we speak, sign and write language and even, as we showed in Chapter 2, the judgements we form about others’ intelligence, character, trustworthiness and morality. As important as such decisions can be in the lives of individuals and in how people interact within and outside social groups and institutions, we wish to contrast this broad and informal sense of language decision-making with more conscious efforts to modify and regulate the way others use language, including stipulations concerning the languages and varieties that are privileged, permitted, discouraged and even forbidden in settings such as schools, courts of law, hospitals, government offices and other institutions and workplaces. Language decision-makers at this second level include teachers, textbook writers and material developers, language therapists, lexicographers and translators, as we describe in Parts B and C. Although these language professionals may not consider themselves language planners, we argue that their decisions about language and the actions they take based upon such decisions are examples of language planning in action. Indeed, although less heralded than announcements of government policy, their overall effects may be more important, although less coordinated and even less predictable, than the outcomes of official or formal language policies (Eggington, 2002). The third level of language decision-making considers the work of applied linguists whose work is explicitly aimed at formulating and implementing language policy and at monitoring the outcomes of language plans and policies. In this chapter we are primarily concerned with language decisions made at these last two levels.

Language Policy, Language Planning and Language Practices

Thus far we have discussed different levels of language decision and whether policies are implicit or explicit, but what is it exactly that is being planned when language planners plan? Joan Rubin (1983) makes a useful distinction between language policy and language planning, in which policy is the legal or statutory measures intended to regulate language use, and planning is the practical implementation of these policies, i.e. the associated goals, strategies and means of assessing progress and outcomes. Here’s an example, from the Bibliothèque et Archives Canada (Library and Archives Canada; LAC), which is charged with collecting and preserving Canada’s documentary heritage and making it accessible to all Canadians.

LAC respects the Official Languages Act … and relevant Treasury Board policies. All LAC information is available in both English and French. Visitors should be aware that some information from other organizations is available only in the language in which it was provided. Original materials presented on the LAC website, such as documents, and audio and video recordings, remain in their language of origin. LAC creates archival descriptions and catalogue records only in the original language of the item.

(LAC, 2008)

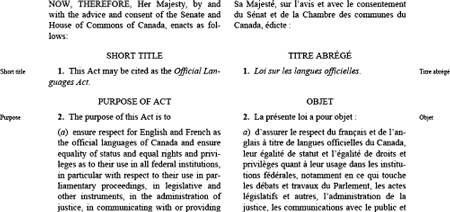

So the Library’s language planning process is set by Canadian national language policy, the Official Languages Act (Figure 5.1). You can read this and (apparently) all other official information in French or in English.

Figure 5.1 Extract from the Official Languages Act of Canada

To enact the policy in a systematic way, the Library has developed a plan for documentation and public access of the materials it collects, preserves and displays digitally and in manuscript form. Its language planners have also set limits on the institution’s linguistic responsibilities under the plan: visitors to the website are advised that materials are presented in their original language (thereby cutting out their applied linguistic translator colleagues!).

Spolsky (2004, p. 222) also distinguishes between language policies and language practices, observing that ‘the real language policy of a community is more likely to be found in its practices than in its management’. Together with Rubin’s (1983) definition, this suggests a hierarchy in which actors with diverse and sometimes competing interests do language planning work at one or more of three different levels. Indeed, a significant challenge for language policy and planning efforts is that policy, planning and practices are seldom in neat alignment. For example, Baquedano-López (2004) describes a case in Los Angeles, where the passage of an anti-bilingual education referendum by California voters (policy) in 2000 led the Catholic Diocese in that city to stop offering catechism and other religious services in Spanish (planning) in local churches, despite the fact that the great majority of parishioners were immigrants from Mexico, El Salvador and other Latin American countries who had originally joined the church because of its Spanish-language services. In practice, however, church workers, many of them immigrants themselves, continued to use Spanish, and the ban proved unworkable. This case is illustrative because it shows how a language policy, in this case an electoral decision to restrict the use of languages other than English in the domain of public education, was applied in a different domain (religion) and resulted in a language plan that was ultimately resisted by local people.

Language planning orientations

Language orientations refers to the idea that language planning efforts of all types can be characterized as approaching language from one or more of three primary stances: language as problem, language as right and language as resource. Conflicts in orientation can explain why language policy and plans are so difficult to implement.

One of the best-known and most frequently cited notions in the field of language planning is the model proposed by Richard Ruiz (1984), who described three primary language orientations:

Language of wider communication (LWC) refers to a language or variety that is used across communities and regions. The term is completely relative and context dependent, of course; Kiswahili is an LWC in East Africa, but not in Asia or Europe. Similar to lingua franca.

For example, the Chinese language planners who made Mandarin Chinese and Putonghua script obligatory in school presumably viewed both the spoken language and the written script as useful resources for all students. In contrast, as Ruiz and many others have since noted, while dominant languages and languages of wider communication (LWC) tend to be viewed, including by many speakers of minority languages, as resources, minority languages are often regarded as problems. This distinction helps explain the remarkable successes of some government-led or government-backed efforts, such as the revitalization of Hebrew in Israel, and the more modest gains in others, such as Welsh (Huws, 2009; Romaine, 2009). For many Israelis, Hebrew has been perceived as a resource, necessary for connecting to sacred texts and religious practices and for communicating across the language differences of newly arrived immigrants. However, in the case of Welsh (banned altogether from official affairs between 1536 and 1942), the right to use Welsh in court was not initially absolute but rather allowed only when a speaker admitted to being unable to use English well enough to stand trial in that language. Even under subsequent legislation guaranteeing the right of Welsh speakers to use Welsh in the courts without restriction, court workers report that

[w]hat tends to happen with defendants and witnesses too, is that they feel that they don’t want to cause any bother for the court, and they think that by asking for something in Welsh, they’re being difficult, you see, so they’re like, ‘no, it doesn’t matter, I’ll do it in English’ even though the offer’s there and the court, the police and the prosecutors are quite willing to conduct cases in Welsh, people feel they’re putting someone out by asking for that.

(Huws, 2009, p. 68)

Thus, even in cases where courts and other government institutions have adopted a language-as-right orientation, the clients who could presumably benefit may avoid the minority language, based on a language-as-problem orientation.

Implicit and Explicit Language Policies

Another way to think about language planning is to consider the scope of decisions, whether they are made in, and with reference to, public spheres, such as government, schooling, health care and other basic services, or about more private spaces, such as a multilingual couple’s decision to raise their children in a particular language or languages. Language decisions made about public spheres and spaces may seem to automatically qualify as examples of explicit policies, but this is not always the case. Consider the case of Tigrinya, the dominant language in the federal region of Tigray in northern Ethiopia. Policy decisions to support Tigrinya as the language of instruction from primary school have had the unplanned consequence of reducing teaching in other regional languages (such as Afar, Saho, Agew, Oromo and Kunama). The introduction of English in the first year of primary school before Amharic, the language of the Ethiopian state since the thirteenth century, in year three, is also a matter of controversy and an example of implicit policy (Lanza and Woldemariam, 2009).

An example of an explicit language policy in a professional sphere comes from a statement by the International Association of Schools of Social Work:

IASSW is a member organisation which is open to all social work educational programmes from all over the world. Therefore its aim is to practise an inclusive language policy, and refrain from becoming an elite organisation dominated by member institutions from the Western world. The language policy and practise is an important factor for deciding whether this is an attractive organisation for a global target.

(IASSW, 2009)

In practice, IASSW’s language policy supports four languages of publication and presentation, English, French, Spanish and Japanese. The Association’s language policy continues:

To make sure a real exchange is taking place and that people from various cultures and language groups have fair opportunities, we need to organise our congresses and meetings in ways so that not the same people are always in an inferior position. Thus, sometimes minority languages might even become dominant ones. People from the dominating languages may have to realise that international communication is a challenge for all of us.

(IASSW, 2009)

This is an example of an explicit policy that acknowledges the intellectual gains that can be developed through collaboration across languages, that recognizes that the spread of English serves some interests better than others, and that seeks more equitable conditions for members.

Conversely, one may imagine that language decisions made in private domains such as the family are more likely to be implicit, unwritten and perhaps even unstated. Perhaps. But think back to your own childhood and see if you can remember any parental or family controls on features of language use in your home. We certainly can: Chris remembers being admonished not to ‘speak common’. For Patrick, there was clear separation (nearly always conscientiously observed) between the acceptable uses of profanity at home and at school. Rachel recalls losing an argument about whether her use of a certain word ‘counted’ as rude and deserved to be punished, or not.

With strong pressures on migrant and minority language children to give up their first language in order to learn a dominant language of wider communication, immigrants and other multilingual families face particularly difficult choices. We know parents who make strong pronouncements on language use in the home, such as: ‘This is a Bangladeshi-speaking home. You will speak Bangladeshi at home’; or, conversely: ‘We have to speak only English at home now. This is the best way to learn English and if we don’t learn English we won’t make it here.’ An informal but powerful statement of a family language policy comes from Turtle Pictures, a work by Mexican American author Ray González describing an adolescent’s frustration with his younger brother’s refusal to speak Spanish – and his plan for remediation:

I don’t know how it happened, but Tony quit speaking Spanish. One day, he just lost it and couldn’t get it back. He grew up in our house listening to Mom and Papa talk Spanish all the time, but Tony’s friends just spoke English. The stupid kid can’t even talk to his grandmother Josefina, who doesn’t speak English. I can’t believe my dumb brother doesn’t want to say a single word in Spanish. Hell, even if he wanted to, he can’t say the words. I’m glad I can speak, read, and write it. When I talk to Tony, who is now thirteen, I cuss him out in Spanish. He knows those words and gets mad at me. He calls me a motherfucker, just like all his rapping friends. They listen to rap CDs where every other word is motherfucker. If Tony doesn’t start speaking Spanish to me, I’m going to steal his stupid music and make him ask for it back in Spanish.

(González, 2000, p. 48)

As these examples suggest, decisions about language use almost always involve much more than language. They are also about identity, communication across and within generations, and the long-term vitality and ultimately the existence of a language or variety in competition with other forms.

Other explicit language decisions are made in the electoral sphere, such as voter referendums that seek to regulate the use of language in public spheres and which minority languages may be used for official purposes. It is worth pointing out that, in the English-speaking world at least, the great majority of legislative and electoral efforts to outlaw the official use of languages occur in the USA. Take, for example, the case of Nashville, Tennessee, a city better known for country music stars than for ethnic neighbourhoods and restaurants, but where the population of immigrants was projected to double between 2000 and 2010 (Mendoza, 2004). Like other communities in the ‘New South’, this historically Euro-American and African American city is the new home of refugees and immigrants from Iraq, Korea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Latin America and especially Mexico. In response to these rapidly changing demographics, a recent referendum asked voters whether the City charter should be amended to specify English as the official language of local government. The proposal read as follows:

English is the official language of the Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee. Official actions which bind or commit the government shall be taken only in the English language, and all official government communications and publications shall be in English. No person shall have a right to government services in any other language. All meetings of the Metro Council, Boards, and Commissions of the Metropolitan Government shall be conducted in English. The Metro Council may make specific exceptions to protect public health and safety. Nothing in this measure shall be interpreted to conflict with federal or state law.

(Nashville English First Charter Amendment, 2009)

In Figure 5.2, an editorial cartoon mocks the Nashville effort to regulate the use of English, contrasting the ‘non-standard’ English spoken by a stereotypical southerner (complete with beer belly and baseball cap bearing the Confederate flag) with the formal variety (and prescriptive grammar lesson) provided by a professionally attired immigrant.

Figure 5.2 Mocking an English-only policy in Nashville, Tennessee (copyright Political Graffiti – Independent Political Cartoons; politicalgraffiti.wordpress.com. All rights reserved)

Supporters of the measure claimed that it was necessary to maintain civic unity and to avoid the financial costs of providing translation and interpreting services for non-English speakers. Business leaders opposed it on the grounds that the English-only message was divisive rather than unifying, and would undermine the city’s efforts to present itself as a cosmopolitan centre and attract international labour and capital to the region (Brown, 2009). A coalition of immigrant groups, led by Kurdish and Spanish speakers and also African American leaders, argued that the proposed ban on languages other than English would harm non-English speakers by limiting their access to health, education and legal services. To the surprise of many observers – and unlike the results in US cities such as Green Bay, Wisconsin and Lowell, Massachusetts – Nashville voters rejected the option of making English their Official and Only Language of local government. The economic argument in favour of multilingualism seemed to carry the day and in January 2009 Nashville voters rejected the English-only measure by a margin of 57 per cent to 43 per cent.

Similar attempts to restrict or ban outright the use of other languages in government have enjoyed robust support at the state level, with thirty US states (including Tennessee, California, Arizona and Florida) adopting English-only statutes since 1981 and another (Oklahoma) currently considering it. Advocates of English-only policies are also extremely active at the national level, with numerous (but as yet unsuccessful) proposals to amend the US constitution to stipulate English as the (sole) official national language. You can learn more about this always fascinating area of language policy and planning from ProEnglish, whose slogans (Protecting our nation’s unity in English and Tired of ‘press 1 for English’? ) appear routinely in English-only literature. For a pro-linguistic diversity and language rights perspective, you can consult the Institute for Language and Education Policy.

Before we leave our discussion of this contentious issue, two final points are worth making. First, although the US situation is somewhat atypical, the underlying conditions are certainly not unknown elsewhere. Migration across linguistic borders is on the rise around the globe, as is attention to the legal and human rights of immigrants and other linguistic minorities. These factors play out differently in different contexts, and even relatively enlightened national constitutions, such as India’s, which recognizes twenty-two official languages, effectively limit access to power and privilege for speakers of other languages (Mohanty, 2009). Second, comparative language policy and planning studies suggest that, across contexts, attempts to limit language rights typically originate with, and are supported primarily by, non-(applied) linguists (Johnson, 2009). Applied linguists generally favour plurilingual policies and language plans that support, rather than limit, the rights of minority speakers.

5.2 Corpus, Status and Acquisition Planning

Cooper (1989) distinguished between three types of language planning: corpus planning, status planning and language acquisition planning. This classification has become a dominant framework for language planning over the past twenty years, so we’ll map the associated territory in some detail here. But we’ll see later, in section 5.5, that there is still much to explore that falls beyond or between the borders of these three domains.

Corpus Planning

Corpus planning refers to language planning that attempts to modify in some way the code of a given variety. Not to be confused with corpus as a digital collection of authentic language.

Corpus planning is the attempt to modify the code itself, including the development of terms for new technologies, processes and services. Changes in computer technologies have been especially productive in motivating the creation of new terms across languages (see Chapter 11). Since many such terms are currently introduced in English, a logical question is whether the term will be borrowed from English or whether an alternative, Indigenous term will emerge or be proposed. Whether Spanish-speaking computer users in Buenos Aires, for example, develop a linguistic preference for a wireless mouse, un ratón inalámbrico, un mouse inalámbrico or some other term depends in part on the efficacy of efforts by national language academies to suggest an attractive alternative term to compete with the English translation (perhaps unsurprisingly, mouse doesn’t appear in the Registro de Lexicografía Argentina or the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, available on the website of the Academia Argentina de Letras).

Diacritics are the ‘extra’ marks required in many orthographies, including the alphabets of French, German, Spanish and the consonantal writing system of Arabic. Placed over, under, next to and even through individual letters or syllabic elements, diacritics change the phonetic value of what they mark, occasionally with important semantic consequences, for example año (‘year’) and ano (‘anus’) in Spanish.

Technology is not the only engine driving the generation of new words, however. As we saw in Chapter 2, languages and language varieties are carried in the minds and literate artefacts of immigrants across regional and national boundaries, and rebuilt, although never exactly the same way, in new ‘host’ communities. When power relations are reversed, former colonial powers may resist language changes that they associate with their former colonies; for example the popular resistance in Portugal to orthographic changes that added three letters (k, w and y) which favoured Brazilian conventions. The reduction in the use of diacritics is also seen to favour Brazilian and African countries, where they are viewed as unnecessary hindrances for mass literacy (Beninatto, 2009). Political boundaries, marked linguistically on maps, are also cause for new words when boundaries change dramatically. For example, the political reunification of East Germany and West Germany into a single state following the fall of the Berlin Wall resulted in the creation of new words, including Mauerspecht, to describe people who chipped chunks off the Wall to sell (Braber, 2006, p. 161), but reunification also led to the loss of some words created and used by East Germans and to a new pattern of one-way movement of new terms from West to East.

Status planning

Status planning refers to efforts to increase or decrease the prestige of a particular language or variety.

Status planning refers to efforts to increase or decrease the perceived status or prestige of a language in a given sphere, for non-linguistic purposes. In the case of the larger languages, status planning is generally conducted by government agencies. For example, although nowadays there is apparently little need to promote the status of English around the world, this has not always been the case. Phillipson (1992) describes linguistic lobbying by the British Council and other government agencies to ensure that English became and remained the language of post-war Europe. Similar actions have been taken to fortify French as a language of international communication and counter the dominance of English. The main player here has been the intergovernmental organization of La Francophonie, with fifty-six member states, set up largely at the instigation of Quebec and France’s former African colonies in the mid-1970s (Dilevko, 2001). The harnessing of language for political and commercial ends is evident in this case: according to the official website, ‘[t]he French language and its humanist values represent the two cornerstones on which the International Organisation of La Francophonie is based’.

In status planning, the establishment, promotion and defence of a ‘standard variety’ and its codification are essential ingredients for government agencies (especially through dictionaries; see Chapter 11). But, as we saw in Chapter 2, languages of wider communication like English have travelled far from the traditional lands of their earliest speakers and are regularly used alongside many other tongues, as additional languages (see Chapters 2 and 9). Indigenized or nativized versions of English therefore compete with Inner Circle standard varieties, with government agencies most often on the side of the latter. Singapore provides a clear example. The government launched a massive ‘Speak Good English’ campaign in order to suppress the local ‘Singlish’ variety, which it sees as an obstacle to the small nation’s continued trade-based economic growth. In a typical scenario in this ongoing debate, officials of the Ministry of Education responded to linguists, stating in an open letter:

While Singlish may be a fascinating academic topic for linguists to write papers about, Singapore has no interest in becoming a curious zoo specimen to be dissected and described by scholars. Singaporeans’ overriding interest is to master a useful language which will maximize our competitive advantage, and that means concentrating on standard English rather than Singlish.

(Ministry of Education, Singapore, 2008)

Covert prestige is a term describing instances in which language pride goes underground due to social pressures. For example, when schools and other institutions frown upon the use of a certain language or variety, speakers often continue to use it as an expression of in-group solidarity and resistance to authority, and it often spreads widely as a result.

While national language policies have concentrated on the economic pragmatism of standard English as a lingua franca, thus greatly diminishing the vitality of Hokkien, Malay and Tamil (Rubdy, 2006), many Singaporeans continue to take pride in the covert prestige of Singlish, and have done some impressive status planning of their own, including publishing the Coxford Singlish Dictionary and maintaining an entertaining and informative website called Talking Cock (a Singlish term for ‘idle banter’). The page’s logo reflects campaigners’ belief that they’re being linguistically repressed (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 ‘Talking Cock’: Resistance to government language policy in Singapore (copyright TalkingCock.com. All rights reserved)

The increasing presence of English around the globe has led to calls to support the language it is seen to displace or is perceived as disfiguring. For example, defenders of Portuguese in Brazil sponsor legislation banning the use of English words on billboards, public signs and advertisements. Rajagopalan reports the arguments of the city government official in San Carlos, Brazil against ‘extraignerismos’ (foreignisms):

How can one explain this undesirable phenomenon [the transformation of Portuguese by the introduction of foreignisms], a potential threat to one of the most vital elements of our cultural heritage, the mother-tongue, which has been underway with growing intensity in the last 10 to 20 years? How can one explain it except by pointing to [a] state of ignorance, to [an] absence of critical and aesthetic sense, and even to [a] lack of self-respect.

(Rajagopalan, 2005, p. 107)

An example of status planning on a more local scale is the decision by a bilingual school to conduct its business in both languages or to privilege the minority language in ways that are not normally seen outside school. Thus, bilingual schools (see Chapter 8 for examples) may decide to conduct public presentations in the non-dominant language or to provide instruction primarily in that language, even though it is not a language of power in that community. Or they may reject the non-dominant language in favour of a dominant one. In many cases the decision is out of schools’ hands. In the largely Uyghur-speaking Xinjiang province of China, use of Han (Mandarin) Chinese in schools is mandated by the central government in Beijing, independently of local concerns. A teacher who works with both local Uyghur and majority-Chinese Han students told a language planning researcher that schools should teach all students in both languages and that the current policy undermined the status of Uyghur people:

If you want to live in our area, Uyghur should be learnt and taught to Han students in schools. The majority of people here are Uyghurs. Of course we need to learn the Han language. Everyone knows that it is important to use the Han language but our Uyghur language is also important. The policy makes our Uyghur students feel our language is not important, so the Han students do not have to learn it. We Uyghurs often regard people who speak our language as friends because they respect our culture – like the Uygur saying, ‘recognize the language not the face to be friends’.

(Tsung, 2009, p. 136)

Acquisition planning

Acquisition planning involves direct instruction, independent language study and other efforts to motivate people to acquire or learn a particular language or variety.

Language acquisition planning (LAP) describes efforts to promote the acquisition of additional languages. Cooper (1989) describes the careful planning and extensive financial and human resources devoted to the delivery of Hebrew language classes for new immigrants in Israel. There are many contemporary examples of immigrants studying the language and literacies of their adopted countries. Bilingual education programmes (see Chapter 8) are prominent examples of LAP, and the choice of instructional methods and materials they employ can also be viewed from a language planning perspective. In the case of languages in which a standard orthography has not (yet) been established, bilingual educators who select a particular orthography for teaching literacy, or a particular variety of a language for developing materials, need to consider the implications of choosing one variety over others. In Peru, for example, applied linguists involved in the development of an orthography for Ashaninka, an Indigenous language spoken in the Amazon region, must attend not only to the selection or elaboration of symbols to best represent the sounds of that language, but also to disagreements among speakers about which variety should be encoded orthographically. Since the Summer Institute of Linguistics proposed the first orthography of Ashaninka around 1960, at least eight different alphabets have been developed (Fernández, personal communication, February 2010). An example of the most recent orthography is shown in Figure 5.4, displayed on the wall behind the applied linguist Liliana Fernández and the Indigenous teachers she worked with to develop teaching materials and grammatical understanding for bilingual teachers teaching in Ashaninka and Spanish.

Figure 5.4 A class of bilingual educators studies the grammar and orthography of the Ashaninka language in Peru

The decision to publish a textbook in a dominant language such as Arabic, English or French would probably not have major implications for the present vitality of those languages on a global scale. However, a decision to use such a book could have very important consequences in schools and small language communities. For example, a Cameroonian school’s decision to adopt a science textbook written in Fulfulde rather than one written in English or French would add massive prestige to the local language, and could be considered an example of status planning. Furthermore, by making available a text in Fulfulde, including the possible creation of new terms (say, in the area of computers and information technology), the decision to educate bilingually or in mother tongue would have implications for corpus planning as textbook writers select terms, consciously or not, that reflect and reinforce certain ways of speaking and writing that are highly valued. Likewise, on the other side of the African continent, the current Kenyan education policy of providing textbooks in English has pedagogical implications: Glewwe, Kremer and Moulin (2007) suggest that the dominant use of English, the third language of many students, in national textbooks limits access to knowledge and that no single curriculum can serve equitably the linguistically diverse peoples of Kenya.

Language-in-education planning refers to instances of language planning that take place within the domain of education and schooling.

As we’ve already suggested, the forms of bilingual education and additional language teaching we describe in Chapters 8 and 9 are major sites of LAP. To the extent that teachers, teacher educators, administrators, curriculum writers and materials developers are directly involved in helping students become more proficient and accomplished speakers and writers of other languages, the applied linguists who hold these jobs can be regarded as language acquisition planners. The term language-in-education planning is sometimes used to describe language decisions that take place in educational settings but are not primarily aimed at language acquisition (Paulston and McLaughlin, 1994). Regardless of the language of instruction, the decision to base assessment of student learning on student writing (essays) vs performance on multiple-choice tests is one example of language-in-education planning (see Chapter 7). Another is the language that is used for testing content knowledge (e.g. which of South Africa’s eleven official languages should be used for national exams?). Faced with the need to make decisions on such issues, teachers and other language professionals often act as de facto planners, responsible for implementing (or resisting) elements of language policies on a daily basis within a particular context.

5.3 Keeping Languages Alive

Language death is the dramatic and unfortunate fate currently facing most of the world’s smallest languages. Linguists sometimes view language death as a process (a language is said to by ‘dying’ when people stop using it) and sometimes as a final state of linguistic rest (i.e. the last living native speaker has died).

In Chapter 1 we made the bleak observation that, based on current estimates, languages are being lost at the rate of about two a month. Painfully, especially for those who love language and languages, the convergence of increased scholarly and public consciousness about language loss and the spread of internet technologies makes it possible for us to witness language death, or at least be informed of it, as it happens in a way that has not been possible before now. For example, as we wrote this chapter, new stories appeared on the BBC, Yahoo and other internet news services announcing the death of Boa Senior, the last living speaker of Bo, a tribal language from the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. Anvita Abbi, the linguist who worked with Boa to document Bo, said that she had outlived all other speakers of Bo by at least thirty years and that ‘she was often very lonely and had to learn an Andamanese version of Hindi in order to communicate with people’ (Lawson, 2010). You can hear a recording of Boa speaking Bo on the BBC News website. (You can monitor endangered language ‘hot spots’ around the globe at the Enduring Voices project, sponsored by National Geographic.)

Language Vitality, Maintenance and Revitalization

Language vitality is a construct used by language planners to gauge the long-term health of a language or variety. Although there are many ways to operationalize this construct, the central feature concerns the transmission of a language from one generation to the next.

Language maintenance implies a focus on keeping a language vital within a given speech community or region. This term is sometimes used to describe bilingual education programmes that aim for learners to retain or further develop their home language while gaining an additional language.

In Chapter 3 we briefly discussed the concept of language death, noting that the accelerating rate of loss was mostly due to the shift to languages of wider communication such as Chinese, English and Spanish. One of the most compelling (and an increasingly widely studied) aspect of language planning involves the vitality or health of a language or language variety. Although there are many other factors involved, as we’ll see, a key factor in the health of a language is the extent to which parents pass it on to their children. In circumstances of extensive shift away from one language to another, a language is said to become ‘endangered’ as the next generation stops acquiring it from dwindling numbers of older speakers. Many Indigenous communities around the world are losing speakers faster than they are raising children in their language(s), and many communities have proposed and carried out schemes for maintaining their language.

Language revitalization is the name given to efforts to stop or slow down language loss and simultaneously increase the vitality of a language in a given community or region. Because the social forces motivating language loss are typically beyond the control of individuals, applied linguists engaged in these efforts are often swimming against the current.

Endangered languages are those which are at risk of being lost due to massive language shift or the death of their remaining speakers.

Schooling is often a component of language revitalization plans, and the role and effectiveness of schools in keeping languages vital have been much studied and debated by applied linguists and the clients they are serving. In Joshua Fishman’s (1991) much-used Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale for evaluating language vitality, being schooled in the endangered language has important effects in favour of language growth. But languages can also be maintained without being taught in school. Intergenerational language transmission is the sine qua non of Fishman’s model: there is little the school can do if children are not already developing their proficiency in the threatened language (whether monolingually or bilingually) by the onset of schooling. With severely threatened languages, of course, this disruption has already happened and there are no school-age speakers. Table 5.2 shows the rubric used by UNESCO in assessing the degree of language endangerment, with Fishman’s metric of uninterrupted intergenerational transmission as the core criterion.

Table 5.2 Degree of language endangerment, UNESCO Framework (Source: adapted from Lewis and Simons, 2010)

Status |

Indicators |

Safe |

The language is spoken by all generations; intergenerational transmission is uninterrupted |

Vulnerable |

Most children speak the language, but it may be restricted to certain domains (e.g. home) |

Definitely endangered |

Children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home |

Severely endangered |

The language is spoken by grandparents and older generations; while the parent generation may understand it, they do not speak it to children or among themselves |

Critically endangered |

The youngest speakers are grandparents and older, and they speak the language partially and infrequently |

Extinct |

There are no speakers left |

Of course, because languages are not uniformly distributed across generations, households or communities, it is true that a language can be vital in the life of some users while others in the same community are losing or regaining their ability to communicate in that language. This is the case in Ika-speaking communities of Arhuaco Indians living in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern coastal Colombia. With snow-capped mountain peaks rising within view of the Caribbean, this region is home to a remarkable linguistic and biological diversity. Trillos (1998) described the language and cultural vitality of Kogui, Kankuamo and Ika speakers living in the Sierra Nevada, and found that all three languages are under stress from Spanish and that the Indigenous languages are most vital in the towns at the highest elevations. Murillo (2009) describes an example of local language planning in an Arhuaco community. Her ethnography of language and literacy in an Ika/Spanish bilingual school and community revealed an issue in language planning that has received little attention: the role of Indigenous cosmology and world view as influences in a decision to support mother tongue education. Murillo concluded that, in a community where language use is guided by spiritual leaders who remind people how to be Arhuaco, some speakers strongly support the use of their first language for literacy instruction, but their goal is not to promote widespread literacy in Ika, nor to use Ika as a bridge to development of Spanish literacy. Rather, this local language policy – specifically the decision to teach reading and writing in Ika in the village of Simunurwa – is attributed to the elders’ desire to maintain and affirm Arhuaco identity among the youth, and also because Indigenous identity offers some protection against being drafted into the paramilitary forces and, consequently, the violence surrounding the Sierra Nevada.

Evaluating Language Maintenance Efforts

Can language really be planned? This question was posed in the title of a now classic work in the field of language planning (Rubin and Jernudd, 1971), written during the nation-building period that former European colonies in Africa and Asia were engaged in during the 1960s and 1970s. In those heady days for the emerging field of language planning, applied linguists consulted with education leaders of emerging and newly independent governments on the question of which languages would be taught in schools and universities, with obvious consequences for teacher preparation, the creation of textbooks, tests and other learning resources, and the development of the corpus (via lexicography, for example; see Chapter 11).

The difficulty of predicting, much less directing, changes in language use with any degree of certainty has led language planners to consider factors in addition to language. For example, in parallel with the social sciences generally, there is a consensus that understanding the material and social conditions in which language problems are embedded is fundamental to effective planning for change. And scholars have become interested in, and now understand, more about how people’s beliefs about language (their language ideologies) influence how they take to, comply with or resist government proposals for language change, such as changes in the language of schooling. The linguist Colin Williams (2009) has identified thirteen reasons why language policies suffer in implementation, ranging from team competence (the ability of language planners to work with team members with other disciplinary expertise), to limitations in software and technical vocabulary, to lack of financial resources to pay translators, interpreters and teachers. So, with this greater sophistication, are we closer to determining whether language maintenance can be planned?

Language shift refers to the process in which speakers, individually or collectively, abandon one language in favour of another. ‘Reversing language shift’ entails efforts to change the conditions that contribute to language loss (in other words, revitalization) .

At the risk of not answering the question, perhaps it is best to say that some aspects of language are easier to plan for than others. For example, from studying the effects of outright bans on certain languages in schools (Hawaiian for most of the previous century; the ‘Russification’ of the former Soviet Union beginning in 1938; virtually all Indigenous languages in Canada and the United States for most of the histories of those countries) language planners know that the imposition of monolingual language policies on multilingual groups can cause great and lasting harm. On the other hand, undoing or reversing language shift seems to be much more difficult to plan effectively, even though planners apparently have years in which to try to stave off language death for endangered languages. UNESCO’s language endangerment scale (Table 5.2), which pinpoints the language of childhood as the most important difference between ‘safe’ and ‘vulnerable’ status, suggests that the language policies and practices of schools have the potential to support or undermine the vitality of non-dominant language. The history of Indigenous languages in schools is such that, in many cases, people are under-standably reluctant to bring them into schools now. Bessy Waco, a Chemehuevi speaker in Arizona who taught a white linguist to speak her language in the 1960s, explained why some community members would not speak Chemehuevi with whites: ‘When I was a little girl they whipped me for speaking Chemehuevi. Now a white man comes and wants to learn my language. White men are crazy’ (Major, 2005, p. 525).

Language policy and planning is still a young discipline compared to some other areas of applied linguistics such as language teaching, translation and lexicography. Like its sister disciplines, it is thoroughly grounded in eurocentric ideas about language and knowledge that guided the ‘discovery’ and cataloguing of non-European languages. Makoni and Pennycook (2007, p. 13) remind us that the names of many of the languages and language groups that planners and policy makers work with today are the products of European colonial rule and the imperial desire for order: ‘From the muddled masses of speech styles they saw around them, languages needed identification, codification and control: they needed to be invented: African languages were thus historically European scripts.’ This ontology produces a paradox for the field: ‘If the notions of language that form the basis of language planning are artefacts of European thinking, language policies are therefore (albeit unintentionally) agents of the very values which they are seeking to challenge’ (Makoni and Pennycook, 2007, p. 12).

Similarly, early language planning efforts have been critiqued for assuming a rational model of language decision-making, that is, for projecting language policy outcomes on the assumption that people would make language choices and support policies that (so many planners and policy-makers believed) were in their own economic and other interests. Thus, applied linguists and others involved in these efforts often operated in the belief that specific recommendations (for example to select and codify the dialect spoken in national capitals or centres of economic power) made economic sense and would be accepted by speakers, over time, as the most appropriate route to national economic development. Similarly, newly independent governments’ decisions to maintain colonial languages such as English and French over Indigenous languages for the purposes of education and government were regarded as ‘neutral’ or ‘common sense’.

The flip-side of this unwritten corollary was, of course, that the choice of Indigenous language is deemed ‘marked’ and unwise. This sentiment is still heard. Suzanne Romaine (2009, p. 129) points to remarks by the applied linguist Henry Widdowson that the government of Nunavut, a federal territory in northern Canada, had erred in choosing Inuktitut to be the language of government: ‘[Inuktitut] creates tremendous problems because it is a pre-literate language not suited for use in complex legal and bureaucratic procedures.’ Romaine further reminds us that Welsh, Indonesian and Basque are among the languages that have recently expanded to meet the needs of government as a language of state. Tollefson (2002, p. 5) summarizes this critique by noting that ‘traditional’ language policies are assumed ‘to enhance communication, to encourage feelings of national unity and group cooperation, and to bring about greater social and economic equality’. A critical approach to language policy and planning places front and centre the question of who decides what, for whom and in whose interests?

5.4 Planning for Access to Services

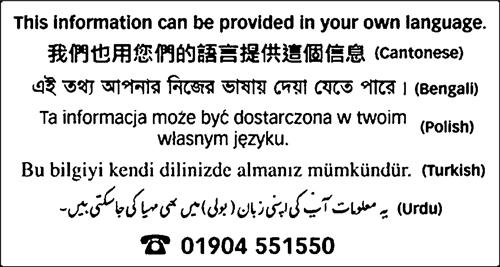

Fostering access to public services is another arena of action for language planners and policy-makers. It is commonplace these days to see signs like that in Figure 5.5 on local authority websites and in printed information. In Chapter 3 we saw an example from a London-based public information campaign to raise awareness of Braille, the writing system for the blind. If you live in a city, depending on its material resources, a quick survey of public access points such as public signage for bathrooms in airports and other public buildings, and the instructions written on automatic bank tellers, vending machines, etc. may reveal that Braille, in addition to notices written in spoken languages, is being planned into the design of these service-oriented texts. Public announcements for services in multiple languages are adding to the linguistic landscapes of multilingual cities, an idea we’ll return to at the end of the chapter (see pp. 121–2).

Figure 5.5 Multilingual services on the York City Council website in the UK

Ensuring that language differences don’t limit clients’ access to education, literacy, health, legal services, employment and technology can challenge the abilities of even linguistically enlightened governments. Recall the English Only referendum facing voters in Nashville, Tennessee, that we described at the beginning of this chapter (pp. 105–7), which was opposed by immigrant groups on the grounds that English-only legislation would undermine the ability of immigrants and other non-fluent speakers of English to obtain access to quality health care services. In Wales, the National Health Proposal calls for health care professionals to learn the Welsh language to be able to care for elderly speakers (Bellin, 2009). But in Peru the lack of Quechua-speaking health care professionals has been identified as a grave flaw in the provision of reproductive and maternal care for Indigenous women and infants. Amnesty International reported the following testimony from a twenty-four-year-old woman who was pregnant for the fifth time, after two of her children had died:

The first time she [the doctor] didn’t understand what I said to her. I went back and again she didn’t understand. The third time she asked me for my family planning card and I went back with it … I couldn’t speak [to her] … When we went with my husband, then he got the doctor to understand [that I was pregnant]. We’re scared when they speak to us in Spanish and we can’t reply … I start sweating from fear and I can’t speak Spanish … what am I going to answer if I don’t understand Spanish? It would be really good [if they could speak in Quechua]. My husband, when he goes to Lima, leaves me with the health promoters so that they can accompany me. They take me to my check ups and speak to the doctor.

(Amnesty, 2009, p. 30)

To protect the health of Quechua-speaking women and their families, the authors of the report recommend that language support be provided in all health facilities attended by Indigenous women, either through training community members in the health professions or by providing medical interpreters for Quechua/Spanish communication.

This brings us to another vital aspect of planning for access to services: translation and interpreting. If constitutionally guaranteed, how available are they in practice? Arturo Tosi (2006) contrasts the importance of translation in the European Parliament and the limited role professional translators are allowed to play in the translation process. The 1958 Language Charter, the legal basis for European Union language policy, states that all European citizens must be able to read and understand documents and legislation in their own languages (Tosi, 2006, p. 13). This has created a ‘massive’ industry within the EU, ‘the largest translation agency in the world’ (Tosi, 2006, p. 15), in which translators work individually on sections of texts rather than on whole texts or through collaboration. Translators often work through translations rather than from original documents in the source language.

Furthermore, ‘translators are not encouraged to act as mediators between the intentions of writers and the effect of the translation on the readers. Quite the contrary, the rather “mechanistic” procedures they are trained to adopt encourage the straightforward substitution of all items in a text, and the direct transfer of its format and punctuation, from one language to another’ (Tosi, 2006, pp. 14–15). According to Tosi, problems of quality under this arrangement threaten the access to equivalent information for all language groups. Although his proposed solution – to fully involve translators in a badly needed revision of EU translation policy – seems sound, it raises other questions, such as:

How do we determine or certify a person’s qualifications to translate and interpret for official and legal purposes?

How do we determine or certify a person’s qualifications to translate and interpret for official and legal purposes?

What sort of education is needed and available?

What sort of education is needed and available?

Who should pay for the education of these language professionals and how much should they be paid?

Who should pay for the education of these language professionals and how much should they be paid?

We explore legal translation and ethical considerations further in Chapters 10 and 12.

5.5 Language Policy and Planning in Globalizing Times

Critical language planning involves questioning the social causes and ramifications of language plans and policies and their implementation. In line with critical applied linguistics generally, language planning from a critical perspective means asking why and in whose interests decisions about language(s) are made.

In this final section, we raise the question of how language policy and planning have been affected by the weakening of national economies and movement toward global integration. For lack of a more precise term, we’ll call on the overworked but useful notion of globalization. Following Castles (2007, p. 39), we’ll use the term to refer to ‘flows across borders, flows of capital, commodities, ideas, and people’. We’ll examine an ongoing shift in the field, from a concern with describing what governments, institutions and individuals do with language within national boundaries to a more politically conscious, less place-based version. This move has also been described as critical language planning (see Johnson, 2009; Tollefson, 2002):

A critical perspective toward language policy emphasizes the importance of understanding how public debates about policies often have the effect of precluding alternatives, making state policies seem to be the natural condition of social systems … Moreover, a critical perspective aggressively investigates how language policies affect the lives of individuals and groups that have little influence over the policy making process.

(Tollefson, 2002, p. 4)

From this perspective, we consider two interrelated areas that are rapidly growing beyond state control: language and poverty, and language and immigration.

Language Planning and Poverty

The study of the connections between language and poverty is a rapidly developing area. Because applied linguists often serve clients who live in conditions of poverty (see Chapter 3), our work is regularly shaped by the economic and non-linguistic needs of the individuals and communities we serve. Grenoble, Rice and Richards (2009) point out that while rural poverty associated with linguistic isolation is consistent with maintenance of some Indigenous languages, people who are struggling to meet their basic human needs generally have little energy or time for responding to language shift. Furthermore, there is great inequality of access to public language services such as bilingual education, mother-tongue instruction and community interpreting (see Chapter 10). If such services are not provided by the state, the poor are unlikely to be able to afford them.

Linguistic deficit is a fictional creature that has, nonetheless, been the subject of much discussion and lament by non-linguists, particularly when applied to the language abilities of children from marginalized groups.

As scholars from various disciplines consider the interrelationship between economics and language, they can stumble over, and be misled by, some of the dead ends we presented in Chapter 1. For example, there remains a strong tendency to assume that the lower levels of formal education and the ‘non-standard’ ways of speaking and writing that are associated with communities living in poverty are a strong index – or, worse, predictor – of their intelligence (see dead ends 4 and 6, pp. 8–9 and 10). While conditions of poverty can indeed truncate or otherwise limit our exposure to certain experiences and discourses, making it more difficult to develop academic literacy, it’s an oversimplification to see economic status as inevitably associated with linguistic deficit. And yet the assumption is highly resistant to correction, as can be seen in the US educationalist Ruby Payne’s (2008) claim that the vocabulary and language development of children living in poverty in the urban US is slower than that of middle-class children. When incorporated through language planning into curriculum and instruction, such claims would be problematic for learners in any group, but they may be especially harmful for the educational futures of children who are also linguistically marginalized. Although scholars have provided empirical evidence to discount so-called language deficits for the poor (Dworin and Bomer, 2008), the belief that poverty causes significant linguistic problems is a persistent barrier to equitable education for language minority students.

Another angle from which language planners consider language and poverty is to ask how income relates to an individual’s ‘language attributes’ (Vaillancourt, 2009, p. 153). Planners use language and economic data from government census records and large-scale surveys on economic well-being and educational attainment. Because these data are reported rather than observed or independently confirmed, and because questions about language attributes are not consistent across measures, it’s important to remember that they’re only getting a part of the picture. It’s also important to keep in mind that any relationship found would be correlational (e.g.French/English bilingualism could be co-present with high levels of income) rather than causal (French/English bilingualism helps make people well off).

So with these caveats, and understanding the limitations of the data, what do we know? The Canadian province of Quebec has been a focal point for this type of language and poverty research, where language planners are interested in the connections between language spoken, income and gender. Setting aside the effects of education, François Vaillancourt (2009) and colleagues examined the income of Anglophone and Francophone men and women, and found that men of all language backgrounds earn more than women of comparable language backgrounds. In other words, language does not offset gender bias in the pay of women workers. However, within gender, French/English bilingualism in Quebec correlates highly with higher incomes for Francophile men and women and for Anglophile women. English monolingualism correlates highly with higher incomes for Anglophile men. Although these findings do not explain why these factors co-occur, they highlight the fact that the economic advantage of bilingualism is shared by some groups, but not Anglophile men. This information could be useful to politicians and policy-makers who are gauging support for public policy that privileges or fosters bilingualism, and who want to know how key demographic groups may vote on a referendum.

Specialists who study the relationship between language and poverty have pointed out that there are other measures of poverty in addition to the economic measures of interest to governments and international aid organizations. Among other non-monetary measures, Vaillancourt (2009) highlights nutrition, access to health care and educational poverty. In this chapter we’ve seen examples of how language policy-makers and planners are involved in efforts to influence the level and quality of people’s formal education, to shape qualifications for employment and to provide access to health care. In line with Ruiz’s (1984) Orientations model (discussed on p. 103), language planners interested in poverty can view language diversity as a resource. For example, scholarship on the relationship between linguistic diversity and biodiversity suggests that human and plant and animal diversity is put at risk when the lands and economies of Indigenous communities are threatened, and the way of life that supports the intergenerational transmission of the Indigenous language is stressed and disappearing (Murillo, 2009; Romaine, 2009). While there may be value in determining a formula to calculate the economic dimensions of language loss within a larger pattern of diversity loss, there are also human costs that are difficult to calculate and to understand, but which language planners must reflect on.

Language Planning and Immigration

The field of language planning emerged as a result of the formation of postcolonial states, but the most dramatic events driving it today are related to migration and immigration across linguistic and national borders. There are patterns in these movements: at unprecedented levels, migrants are moving from poor areas to the former colonial centres, from south to north, and from rural to urban areas. Increasingly, these movements are intergenerational, and involve men, women and children. Along with the explosion in digital communication technologies, the flow of people to new homes within and across national boundaries stretches previous understandings that the locus of language planning work is the state. How to plan for Tagalog/Filipino, for example, when more than two million speakers are living outside the Philippines? Or keep up with Arabic, with 220 million speakers spread across nearly sixty countries (Lewis, 2010)? Immigration increases multilingualism in communities, sometimes very rapidly. Language is one of immigrants’ primary resources and tools for making it in their new society, but how will host communities receive speakers of their language(s)?

As the result of mass internal and international migration, there is a pressing need to provide language classes for child and adult learners, and also for basic services such as public education, health care, and legal and public information in non-dominant languages. White and Glick (2009, p. 58) distinguish between immigration policy and immigrant policy, the former regulating ‘who gets in’ and the latter concerned with what kind of treatment they get. Two areas where applied linguists participate in, or challenge, immigration policy are the use of language analysis to determine national origin (see Eades, 2005; and Chapter 12) and language testing to manage immigrant numbers (see Shohamy and McNamara, 2009). Immigrant policy, which includes language classes, access to services and naturalization, is the site of more applied linguistic work. Eva Codó (2008), for example, analysed language use in a state immigration office in Barcelona, finding that Spanish was the only ‘legitimate language’ immigrants could effectively use in seeking Spanish citizenship. She described how the hiring of only Spanish-born interpreters led to a staff of specialists in languages that were not spoken by South Asian clients: predominantly Arabic (but not the variety spoken by Moroccan immigrants served by the Barcelona immigration office) and Russian. Immigration officials would sometimes use English and French with immigrants, but Codó found that most clients either attempted to speak Spanish or obtained the services of another immigrant who could speak Spanish with immigration officials on their behalf.

Each immigration context is unique, with key variables including the language(s) spoken in the sending and host community; the immigrants’ level of formal education; and the reception that immigrants receive from officials and the host community. Family experience with migration/immigration has also been identified as a factor in the decision to migrate and the choice of a new community; pathways to migration seem less daunting if family support awaits migrants in the host country. The move to an urban area usually signifies increased access to education, employment, housing and health care, services through which migrants may also become clients involved in or affected by language policy and planning. Educating immigrant children is a challenge that faces schools in many countries (although migration often signals the end of formal schooling for young adults). Because of the increasing numbers of immigrant youth, bilingual education is perhaps the area of applied linguistics and language planning most influenced by immigration, and in Chapters 7 and 8 we look at language-in-education policies designed to serve migrant students.

Linguistic landscapes are visual representations of language use in a community. By mapping the presence of signs, posters and other publicly displayed texts, applied linguists form a picture of the relative vitality of languages at a particular place and point in time.

We close this section with a brief look at the concept of linguistic landscape (LL) as an emerging methodological and conceptual approach for understanding how migrants contribute to language use in their adopted communities. The term originated with Landry and Bourhis’ (1997) study of the distribution of languages on public signage in Canada and the reactions of Francophone high school students, the notion being that the positioning and density of texts in a specific language were an index of its vitality in that particular setting. Spolsky (2004) comments that ‘linguistic cityscapes’ might be a more accurate term, given that studies have mainly taken place in multilingual cities such as Quebec, Jerusalem and Brussels. Shohamy and Gorter (2009, p. 6) write that ‘the connection of linguistic landscape with language policy is a natural one, given that linguistic landscape refers to language in public spaces, open, exposed, and shared by all’.

As a means of recording and understanding the written language that is visible in the public space, LL is well suited to capturing the linguistic contributions of immigrants and the hybrid linguistic outcomes achieved through contact between immigrant languages and the dominant language(s) in the host country. The approach is based on the premise that migrants are agents, that is, they are ‘not isolated individuals who react to market stimuli and bureaucratic rules but social beings who seek to achieve better outcomes for themselves, their families and their communities by actively shaping the migratory process’ (Castles, 2007, p. 37).

Figure 5.6 shows an apparently homemade advertisement for a cleaning service. We found this ad taped to a supermarket window in a Chicago suburb that is home to many immigrants from the Mexican state of Puebla. The sign for this cleaning service contains several words with unconventional spelling in English and in Spanish, and yet it contains other elements suggesting that the author is familiar with design and is an experienced computer user. Aurora’s poster was surrounded by similar texts, some handwritten and others more professionally produced. There were photographs, mostly photocopied, of cars, washing machines and other items for sale, and descriptions of homes for sale and rent. All of the advertisements contained elements of English and Spanish.

Figure 5.6 A bilingual advertisement for cleaning services

Advertisements like this one can be analysed on two levels. From the bottom up and on the level of the individual decision-maker, we can consider the author and anyone she may have enlisted to help her produce her poster. Photographing and analysing advertisements and publicly displayed texts can tell us something about the new ways immigrants are using language to support themselves in the host country. Additionally, we can ask residents for their interpretations of locally produced advertisements. For example, Collins and Slembroucke (2007) asked Turkish immigrants and Dutch-speaking Belgians in Belgium to interpret photographs of bilingual signs in shop windows in Ghent, and reported that immigrants and non-immigrants had very different interpretations of these texts and different opinions regarding the use of non-conventional spelling and other non-prestige forms of language use.

Language planners are also beginning to use LL at the level of community to measure the (co-)occurrence and positioning of languages in multilingual cities. For example, Lanza and Woldemariam (2009) mapped the linguistic landscape of the northern Ethiopian city of Mekele to study language ideologies surrounding Tigrinya (the regional language), Amharic (the dominant national language in Ethiopia) and English. Their corpus consisted of 375 signs displayed in a shopping district, approximately two-thirds of which were bilingual. Nearly all bilingual signs involved English, and only a very few simultaneously displayed Tigrinya and Amharic. None of the other regional languages spoken in Mekele were attested on signs. These written data can be collected easily and compared over relatively short periods of time, for example to see if the recent adoption of an ethnic federalism policy tilts public signage in favour of Tigrinya. At this level, LL data complement census data about what languages immigrants are speaking and where.

5.6 Roles for Applied Linguists