language (especially the relationship between language, thought and society);

language (especially the relationship between language, thought and society);Chapter 4

[D]iscourse Analysis is one way to engage in a very important human task. The task is this: to think more deeply about the meanings we give people’s words so as to make ourselves better, more humane people and the world a better, more humane place … If such talk [seems] too grandiose to you, then, I suggest, you’ve been reading – and doing – the wrong academic work.

(Gee, 2005, p. xii)

Discourse surrounds us in everyday life, often in ways that seem so normal we barely notice them: from the combining of texts and images in school books, on food packaging and road signs; to greetings between friends and between strangers; to the writing of emails and academic essays. As these examples imply, the word discourse refers to spoken or written language (perhaps in combination with images) used to communicate particular meanings. Discourse analysis is the practice of exploring what kinds of speaking, writing and images are treated as ‘normal’ (and ‘abnormal’) in real situations, and the proportions, combinations and purposes of discourse that are conventionally acceptable (or not) in these situations.

The aims and methods of discourse analysts have varied over time and across a broad range of academic disciplines. Aims have included, for example: the description of contextualized language use, the explanation of how discourse is processed in the mind, and the consideration of how discourse can both reflect and create a particular version of events, objects or people (Pennycook, 1994a). Broadly, analysts interested in achieving the first two of these three aims have tended to conceptualize discourse from a linguistic or psycholinguistic perspective, in which language provides the components of discourse and the mind is the ultimate seat of language. In contrast, analysts interested in achieving the third of the three aims have tended to conceptualize discourse from a sociolinguistic perspective, in which understanding of the mind (and, more generally, what it means to be a person, or a member of a particular group or culture) is created (not just expressed) in and through discourse. In other words, for discourse analysts working within a social rather than a cognitive tradition, mind, people and cultures are the product of discourse, not its source (though see the section on discursive psychology on pp. 87–8 for a new approach to the relationship between mind and language). For a brief historical overview of developments and a discussion of definitions of discourse analysis, see Jaworski and Coupland (1999, pp. 1–44).

As an applied linguist, you may be called upon to deal with problems which are conceptualized by your clients, and the language professionals who work with them, as either or both cognitive and social. Therefore we think that it’s important to be aware of all possible dimensions of discourse. With this in mind, we map a variety of approaches to discourse analysis, but with our focus firmly on those which have already proved useful to applied linguists. The usefulness of each of these approaches is important, so in addition to briefly describing its aims and methods and mentioning some of the scholars associated with an approach, we have given an example of a study which uses the approach to illuminate a language problem faced by an individual (or groups of) user(s).

In conversation analysis, repair refers to the ways in which speakers correct unintended forms and non-understandings, misunderstandings or errors (or what they perceive to be such) during a conversation. A self-initiated repair is when the speaker corrects themself: ‘You know Jim, erm, what’s his name , John?’ An example of an other-initiated repair is when the listener replies: ‘Hmm? ’

If you think that analysing discourse in your own professional context, or for a course of study you’re engaged in, is something that you would like to do, how do you know which of the approaches described in this chapter to choose? Unfortunately, there isn’t an easy answer to this question, and before you make your decision you will probably read a lot of research reports (published in the usual places: academic journals, books, profession-specific newsletters and websites) on the topics and client groups you are interested in. While you’re reading these reports and comparing the context and the clients with your own, you may also want to consider the approach to discourse analysis used by the practitioner/ researcher and whether such an approach would be feasible in your own context. One way of starting to think about an approach is to look up the study we mention at the end of each sub-section (in 4.2 and 4.3) and consider how the context being researched is similar to or different from your own. Another way of choosing an approach to discourse analysis is to think about which topics or themes (as mentioned in each of the sub-sections in 4.2 and 4.3) the various approaches have been associated with, and whether these are topics or themes which interest you. For example, if you are a teacher interested in error correction in classroom discourse it would be useful to look at conversation analysis (see p. 87) and the considerable body of work by conversation analysts on repair (see, for example, Seedhouse, 2004).

Choosing an approach to discourse analysis that other practitioners/ researchers have used to explore the topic/theme/context/client group you are interested in has the obvious benefit of facilitating comparisons between your own findings and those of other discourse analysts. On the other hand, you could consider using an approach to analysis that has been used in a context that is similar to yours in some ways and different in others (a possibility we’ll come back to in section 4.4). For details of the techniques associated with each of the approaches to discourse analysis described in sections 4.2 and 4.3 and demonstrations of how these techniques work on actual data, you could look up the studies that are mentioned as examples or check any of the books in the list of further reading at the end of this chapter. Many of the approaches also have frequently updated websites, often maintained by users of the different approaches, and, where relevant, these are noted in the text and included as links on the companion website.

It’s important to remember that discourse analysis, just like all other kinds of analysis, is not a neutral, objective method for describing language use as it ‘really is’ (though the proponents of certain approaches to discourse analysis may claim otherwise). All the different approaches are underpinned by assumptions about:

language (especially the relationship between language, thought and society);

language (especially the relationship between language, thought and society);

relationships between the practice of analysis and ‘real life’;

relationships between the practice of analysis and ‘real life’;

the kind of changes we, as applied linguists, should be helping our clients make.

the kind of changes we, as applied linguists, should be helping our clients make.

In most cases, discourse analysts are likely to bring these assumptions to the surface rather than pretending that they don’t exist. Often, as part of the process of selecting and justifying their analytical choices, analysts will make their assumptions accessible for inspection (and challenge) by the participants in their analysis. Ultimately, what approach to the analysis of discourse you take will depend on the types of questions you and your clients are asking about your situation and the types of text that are available for analysis. No one approach is necessarily better than any of the others; none of the approaches is an end in itself – all are simply tools in our quest to understand the real language issues encountered by our clients.

Here’s the route we’ll be taking in this part of the applied linguistics map. In the next section, 4.1, we stress the centrality of discourse in social processes as a prelude to describing some of the approaches to discourse analysis which have proved useful to applied linguists, briefly reviewing the typical aims, methods and principal scholars associated with each approach. We have divided up the approaches into two sections, 4.2 for those approaches whose origins are most closely tied to linguistics and 4.3 for those approaches whose origins are most closely associated with sociology, ethnography and cultural theory. (Treating the various ways of doing discourse analysis as separate sub-sections has the unintended side-effect of implying clear-cut differences between a complex and interrelated set of approaches which, in addition, can be mixed and matched to suit an applied linguist’s specific needs. This is an issue to which we give further thought at several points in this chapter.) After our tour of approaches, we draw out some of the major themes that discourse analysts have explored, in section 4.4, and then conclude, in section 4.5, with some final thoughts about how doing discourse analysis can help applied linguists in their work.

4.1 The Pervasive Relevance of Discourse (Analysis)

As we have already said, discourse is analysed in a variety of disciplinary fields, including (but not limited to) linguistics, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, literature and psychology, by people with a wide variety of aims, methods, theories and topics. What all these discourse analysts have in common is an interest in the following question: how does the study of discourse illuminate cultural and social processes? As applied linguists, we can probably narrow down this general question to: how does the study of discourse illuminate the cultural and social processes that can lead to language-related problems, and solutions, for our clients (the key populations of Chapter 3)? But perhaps this is too narrow a question, in that it doesn’t acknowledge the contribution that sensitivity to language issues, a sensitivity characteristic of applied linguists, can make to the study of general cultural and social processes. Although the focus of this book is indeed language-related problems and solutions, this chapter is an appropriate place to remind ourselves of the importance of language in cultural and social processes as well as its importance as a product of culture and society (an interdependence we come back to later in this chapter in a section on texts and contexts, on pp. 91–2).

Phatic communion is a term used by Malinowski to refer to communication which is not intended to convey information but which functions as a way of creating or maintaining social contact. In English ‘How are you?’, ‘Have a nice day!’ and ‘Terrible weather!’ are examples of phatic communion.

In an early study of the management of social relationships through discourse, the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1999 [1923]) observed how the meaning of much small talk is almost entirely context-defined. Employing the phrase phatic communion, he showed how these predictable patterns of ritual text help create positive feeling between speakers – not because of what the words mean, but because of what they do. By filling in silences or helping to start and end new topics, the meaning of these patterns of text is created by the context in which the words occur. Changing the context can change the meaning of the text, as the following example shows. In Scotland, ‘greeters’ employed by a supermarket to stand at the entrance to the shop and tell customers to Enjoy your shopping experience were ridiculed by the very customers the shop was trying to create a relationship with. In this case, the supermarket customers implicitly recognized the social bonding work being attempted by use of ritual text and resisted the exploitation of phatic communion for commercial purposes (Cameron, 2002). The relevance for applied linguists of the judgements all language users make about text, context and appropriacy is very clear: in situations where we are called on to give advice, we should be sensitive to local norms and be disdainful of global prescriptions for effective communication (like the self-help guides that insist we ‘be direct’ and ‘be clear’). Each context is different, and all contexts have their own discourses. We have had enlightening conversations with academic colleagues about the role of discourse in a wide variety of fields, including education, theology, marine biology, geography and business management. The combination of a problem-solving orientation and a sensitivity to local contexts/discourses makes an applied linguist a useful person to have on any team tasked with the investigation of real-world issues.

4.2 Linguistic Approaches to Discourse Analysis

Corpus Linguistics

A corpus (plural corpora) is a digital collection of authentic spoken or written language. Corpora are used for the analysis of grammatical patterns and estimations of the frequency of words, word combinations and grammatical structures. The results are useful in, for example, additional language education, translation, lexicography and forensic linguistics.

Corpus linguists amass (sometimes extremely large) electronic collections of naturally occurring written and transcribed texts (a corpus). The texts are usually chosen to represent a particular variety (or set of varieties) of language, genre or type of language user. By tagging (electronically labelling) selected features of the texts and then using a search engine to sort through the collection of tagged texts, corpus linguistics (CL) aims to explore the extent to which certain features of language use are associated with contextual factors (which could include variety of language, genre or type of language user). By counting how many times a selected feature occurs in the corpus, CL aims to uncover characteristic patterns of language use and to generalize from the collected texts to other texts of a similar type, or to the language as a whole. CL has been used to analyse language by a variety of applied linguists, including those working in forensic linguistics (Wools and Coulthard, 1998; also see Chapter 12), the preparation of bilingual dictionaries (Clear, 1996; see also Chapter 11) and additional language learning (Carter and McCarthy, 2006; O’Keeffe et al., 2007; see also Chapter 9). Taking additional language learners as a type of language user, CL studies have suggested that learners of English tend to overuse adjective modifiers like very (Lorenz, 1998) and high generality words like people and things (Ringbom, 1998), and underuse hedging devices like perhaps and possibly (Flowerdew, 2000). In CL, the features of the linguistic patterns under study are assumed to be ‘in’ the variety, genre or type of language user, independent of the context-specific processes of writing or speaking, or the processes of constructing and analysing the corpus.

There are applied linguists who dispute the validity and methods of CL for solving real-world language problems (for example Widdowson, 2000), though there are also those who argue that CL can be used to investigate not just patterns of linguistic structure and deployment, but also the role of language in social and cultural processes, making CL a possible tool in critical discourse analysis (Baker, 2006), of which more on pp. 88–9. The role of CL in studies of English as a lingua franca is an interesting and a controversial case, with some scholars using CL to try and discover grammar and lexis which are ‘core’ to (typically associated with) all lingua franca talk, regardless of setting, participants, etc. (see Seidlhofer, 2001; and the online VOICE English as a lingua franca corpus). Other scholars have argued for a more ethnographic approach to the analysis of lingua franca talk, emphasizing the importance of methods which are sensitive to the context-specific ways in which speakers adjust their talk to achieve specific goals (Canagarajah, 2007).

Speech Act Theory

Pragmatics aims to understand what spoken (or signed) language means in specific contexts of use, through a description of the relationship between speaker, hearer, utterance and context.

Speech acts are utterances which operate as a functional unit in communication; for example: promises, requests, commands and complaints. In additional language education (especially lesson planning and syllabus design), speech acts are often referred to as functions.

In speech act theory, utterances involve two kinds of meaning: a locutionary meaning, which is the literal meaning of the words and structures being used; and an

illocutionary meaning, which is the effect the utterance is intended to have on the listener.

A perlocutionary act is the effect or result of the utterance.

Speech act theory is part of the wider discipline of pragmatics. The work of philosopher J. L. Austin provided pragmatics with a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between speaker, hearer, utterance and context (Austin, 1975). Using the concept of speech act as the principal object of study, Austin distinguished between the words used in the act (locution), the intention or force of the speaker (illocution) and the effect of the utterance on the listener (perlocution).

Speech act theory recognizes that language is not only a way of communicating ideas, but can also be used, depending on the participants and their sociocultural contexts, to transform their reality. In other words, we say things that not only are judgeable as true or false, but can also perform an action that impacts on the world. A speaker who says, ‘It’s hot in here’ may simply mean to observe that it’s hot (the propositional meaning, or, using Austin’s term, the locutionary force); but they might also be making a request for a window to be opened (the illocutionary force), with the effect that the listener opens a window (the perlocutionary force). In an example of how speech act theory has been used in applied linguistics, Myers (2005) explores the role of language in public opinion research by corporate and government institutions. The study demonstrates how speech act theory can help us to understand the comments of a group of people living very close to a nuclear power plant, a choice of location that might be considered risky or dangerous. The local residents tell an interviewer appointed by the government body responsible for dealing with nuclear waste that, on the one hand, they feel safe, despite their close proximity, but, on the other hand, they don’t want the by-products of the plant, the nuclear waste, to be disposed of near their homes.

Myers points out that one possible interpretation of these seemingly contradictory comments is that a statement of trust in a person or institution can have the perlocutionary force (the effect on the listener) of creating an obligation to be trustworthy. In stating that the nuclear plant is safe to a person they identity with the plant, the locals may be doing something about making the plant safe: via the interviewer, the managers of the plant and the government are reminded that they have an obligation to ensure safety if they are not to fail in the trust bestowed by the local residents. Speech act theory, in this example, helps to show how the meaning of the locals’ comments about safety is more richly interpretable from the perspective of the specific relationship between the speakers, hearers and places involved. The application of speech act theory also helps to explain why other data collection methods, such as surveys, which are not as context-sensitive as a face-to-face interview, have failed to generate much insight into general public opinion (other than the very obvious, like ‘nuclear waste should be disposed of, but not near us’).

The Birmingham School

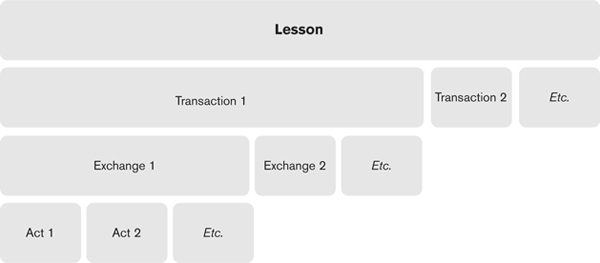

An early use of discourse analysis in applied linguistics was the description of classroom discourse by John Sinclair and Malcolm Coulthard (1975). Developed out of an approach to structural analysis in linguistics, Sinclair and Coulthard’s groundbreaking work identified twenty-two combinable speech acts that typified the verbal behaviours of primary school teachers and their pupils in traditional, teacher-centred lessons. Their model involved a discourse hierarchy composed of units of discourse from the largest unit, lesson; down to transaction (episodes within the lesson usually bounded by discourse markers such as ‘right’ and ‘now then’); then exchange, a unit of discourse comprising combinations of question–answer– feedback moves; and finally the smallest unit, act (nominating students, getting them to put their hands up and so on) (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Sinclair and Coulthard’s discourse hierarchy for traditional teacher-centred lessons (Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975)

Sinclair and Coulthard suggested that typical of classroom discourse was the ‘eliciting exchange’, comprising the three core moves of teacher initiation, followed by student response, followed by teacher feedback or evaluation (IRF/E). For example:

Teacher: |

What’s the past form of the verb ‘swim’? Initiation |

Student: |

Swam Response |

Teacher: |

Swam, good! Feedback and evaluation |

Whilst it is extremely important for raising awareness of teacher talk in general (and starting the debate about the effectiveness of different patterns of talk), the practical difficulty of identifying a one-to-one relationship between moves and speech acts has been identified as a possible threat to the validity of the Birmingham School’s approach to discourse analysis, as has the problem of over-generalization and lack of sensitivity to local context (Seedhouse, 2004).

Systemic Functional Linguistics

Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) is interested in the social context of language. In SFL, language is analysed as a resource used in communication, as opposed to a decontextualized set of rules. It is an approach which focuses on functions (what language is being used to do), rather than on forms.

Drawing on the work of linguist J. R. Firth and Dell Hymes (of whom more in the next section), systemic functional linguistics (SFL) is most closely associated with M. A. K. Halliday (1978, 1994). SFL aims to explore the systematic relationship between the contexts of everyday life and the functional organization of language; that is, what language does in, and for, the situation in which it is spoken or written – in other words, its social purpose. The central claim of SFL is that the structural choices made in the construction of texts are ultimately derived from the functions that language serves in a context of use. Halliday’s framework for describing texts and their social contexts comprises three elements, which together reflect the concept of register we introduced in Chapter 2:

The field of discourse: what is happening? What is the nature of the social action that is accomplished by the text?

The field of discourse: what is happening? What is the nature of the social action that is accomplished by the text?

The tenor of discourse: who is taking part? What kinds of temporary and permanent status and roles do the participants have in the interaction and in other interactions in which they might take part?

The tenor of discourse: who is taking part? What kinds of temporary and permanent status and roles do the participants have in the interaction and in other interactions in which they might take part?

The mode of discourse: what part does the language of the text play (including whether the discourse is spoken or written, and its rhetorical mode: persuasive, didactic, expository, etc.)?

The mode of discourse: what part does the language of the text play (including whether the discourse is spoken or written, and its rhetorical mode: persuasive, didactic, expository, etc.)?

Halliday’s semantic framework for identifying the functions of language also consists of three categories, which are (in a rather simplified form):

The ideational function: how the semantic content of a text is expressed.

The ideational function: how the semantic content of a text is expressed.

The interpersonal function: how the semantic content is exchanged or negotiated.

The interpersonal function: how the semantic content is exchanged or negotiated.

The textual function: how the semantic content is structured in the text.

The textual function: how the semantic content is structured in the text.

SFL uses these two frameworks (which are more detailed and intricate than our summary implies) to explore the relationships between social contexts and functions of language, paying attention to how:

experiential meanings are activated by features of the field;

experiential meanings are activated by features of the field;

interpersonal meanings are activated by features of the tenor;

interpersonal meanings are activated by features of the tenor;

textual meanings are activated by features of the mode.

textual meanings are activated by features of the mode.

The consequence of SFL’s functional approach is a theory of meaning in which text and context are inseparable; language operates in contexts of situation, and social contexts are created by the range of texts that are produced within a community. In an example of how SFL can be used in applied linguistics, Young and Nguyen (2002) compare how a scientific topic is presented in interactive teacher talk with how the same topic is presented in a textbook. The study identifies three aspects of scientific meaning-making: representations of physical and mental reality, lexical packaging and the rhetorical structure of reasoning. The comparative analysis of teacher talk and textbook illustrates the different ways in which students are socialized into thinking and talking about science, as well as making some recommendations for the design of school textbooks.

The Ethnography of Communication

Communicative competence is not only the ability to form utterances using grammar, but also the knowledge of when, where and with whom it is appropriate to use these utterances in order to achieve a desired effect. Communicative competence includes the following knowledge: grammar and vocabulary; the rules of speaking (how to begin and end a conversation, how to interrupt, what topics are allowed, how to address people and so on); how to use and respond to different speech acts; and what kind of utterances are considered appropriate.

Ethnographic approaches to discourse analysis are part of a sociolinguistic tradition and are closely associated with the work of Hymes (1972) (see also Saville-Troike, 2003). With the intention of extending Chomsky’s linguistic competence/ performance model, discussed in Chapter 1, Hymes proposed the construct of communicative competence: knowledge of whether and to what degree an utterance is considered by a specific community or group to be grammatical, socially appropriate, cognitively feasible and observable in practice. Figure 4.2 illustrates some of the elements of communicative competence.

Figure 4.2 Aspects of communicative competence

Hymes developed a framework which analysed communication at three different levels: speech situations (sports events, ceremonies, trips, evenings out, etc.); speech events (ordering a meal, making a political speech, giving a lecture, etc.); and speech acts (greetings, compliments, etc.: see pp. 80–1). Speech events (the middle category) rely on speech for their existence (without speech it would, for example, be difficult, though not impossible, to insult someone effectively). The components of speech events can, according to Hymes (1974), be described using the following eight-part list based on the word speaking:

situation (physical, temporal, psychological setting defining the speech event);

situation (physical, temporal, psychological setting defining the speech event);

participants (for example, speaker, hearer, addressee, audience);

participants (for example, speaker, hearer, addressee, audience);

ends (purposes, goals and outcomes);

ends (purposes, goals and outcomes);

act sequence (message form and content);

act sequence (message form and content);

key (manner of speaking, tone, for example serious, joking, tentative);

key (manner of speaking, tone, for example serious, joking, tentative);

instrumentalities (spoken or written, use of dialects, registers, etc.);

instrumentalities (spoken or written, use of dialects, registers, etc.);

norms of interaction (for example turn-taking) and interpretation (local conventions of understanding);

norms of interaction (for example turn-taking) and interpretation (local conventions of understanding);

genre (for example poems, academic essays, myths, casual speech, etc.).

genre (for example poems, academic essays, myths, casual speech, etc.).

The communicative approach in additional language teaching stresses that the aim of learning a language is communicative competence. Teachers who base their lessons on a communicative approach may follow a syllabus based on functions or topics, teaching the language needed to perform a variety of authentic tasks and to communicate appropriately in different situations.

One important impact on applied linguistics of the ethnography of communication has been in the inspiration of the communicative approach to teaching additional languages (Howatt and Widdowson, 2004; see also Chapter 9). Applied linguists use ethnographic approaches to understanding the discourse of specific communities or groups with which they are closely involved, either through participation in the communities’ usual activities and/or very careful observation. A community could be, for example, people in a courtroom, a family, participants in an online discussion board, a department or team at work, and students and teachers in a classroom. In an example of the latter, Duff (2002) illustrates the use of an ethnographic approach to communication in a study of a UK high school classroom with a high proportion of pupils who are speakers of English as an additional language. A detailed analysis of the classroom talk, from the point of view of the participants, highlights the contradictions and tensions in a teacher’s attempt to encourage her students to respect each other’s cultural identity and difference.

Interactional sociolinguistics

The work of interactional sociolinguists focuses on the fleeting, unconscious and culturally variable conventions for signalling and interpreting meaning in social interaction. Using audio or video recordings, analysts pay attention to the words, prosody and register shifts in talk, and what speakers and listeners understand themselves to be doing with these structures and processes. Gumperz, the founder of interactional sociolinguistics, was mainly interested in contexts of intercultural miscommunication, where unconscious cultural expectations and practices for conveying and understanding meaning are not necessarily shared between speakers.

The approach to discourse known as interactional sociolinguistics was established by a close associate of Hymes, the anthropological linguist John Gumperz (for example Gumperz, 1982), drawing on the work of Erving Goffman (for example Goffman, 1981). Much of Gumperz’s work focuses on intercultural communication and misunderstanding (see pp. 92–4) and aims to show that our understanding of what a person is saying depends not just on the content of their talk but on our ability to notice and evaluate what he calls contextualization cues, which include: intonation, tempo, rhythm, pauses, lexical and syntactic choices and non-verbal signals. Gumperz adapted and extended Hymes’ ethnographic framework by examining how interactants with different first languages apply different rules of speaking in face-to-face interaction.

How this happens, and the subconscious nature of the interpretive processes involved, is suggested by the following example (Gumperz, 1982). Newly hired South Asian airport canteen staff were perceived as surly and uncooperative by their British supervisors and the British cargo handlers they served food to. Observation of the canteen staff at work showed that they didn’t exchange many words with their colleagues, but when they did, the way in which they pronounced these words was interpreted negatively. For instance, instead of saying Gravy?, with rising intonation, as a way of offering gravy, the South Asian staff used falling intonation.

Gumperz describes how the researchers recorded the canteen interaction and played it to both British and South Asian employees, asking them to paraphrase what they meant by each utterance. After several such data sessions, the British employees could see that the South Asian canteen staff were not intending to show rudeness or indifference, but using their normal way of asking questions in that situation. The South Asian employees had sensed for some time that they were being misunderstood but explained this as a reaction to their national origins. Gumperz claims that the discussion sessions, by focusing not on stereotypes or attitudes but on context-bound interpretative preferences, resulted in the acquisition by the staff of strategies for the self-diagnosis of communicative problems (for a similar study of discrimination in the workplace based on a misunderstanding of contextualization cues, see Roberts, 2005).

Contrastive rhetoric

So far, we have been concerned with the organization of discourse within languages. In a much discussed paper, the applied linguist Robert Kaplan claimed that there were differences in the way that discourse was organized between languages. Kaplan (1966) suggested that written texts were organized in ways that corresponded to the ‘thought patterns’ of the following five ‘cultures’: Semitic, Russian, Romance, European and Oriental. For example, ‘European’ writing was supposed to be organized in a linear, hierarchical pattern, whereas ‘Oriental’ writing was spiral and non-hierarchical. Kaplan’s original article has been challenged (including by Kaplan himself) on various grounds (Connor, 2002), including:

its research methods (Kaplan mainly used texts written in English by students studying English in the US);

its research methods (Kaplan mainly used texts written in English by students studying English in the US);

its simplistic generalizations about language and writing within ‘cultures’, and its underdeveloped concept of ‘culture’;

its simplistic generalizations about language and writing within ‘cultures’, and its underdeveloped concept of ‘culture’;

its view of writing as a product, not a process;

its view of writing as a product, not a process;

its implication that other cultures need to learn to avoid ‘bad’ writing;

its implication that other cultures need to learn to avoid ‘bad’ writing;

its conflation of ‘thought patterns’ with the way written texts are organized;

its conflation of ‘thought patterns’ with the way written texts are organized;

its use of the paragraph, not the whole text, as the unit of analysis;

its use of the paragraph, not the whole text, as the unit of analysis;

its lack of attention to the writing styles of different genres within languages or to differences between the many languages in each category;

its lack of attention to the writing styles of different genres within languages or to differences between the many languages in each category;

its lack of sensitivity to the way writers actually shuttle between local and target language practices in their writing.

its lack of sensitivity to the way writers actually shuttle between local and target language practices in their writing.

Contrastive rhetoric compares the organization of texts written in different languages, based on the assumption that there are characteristic patterns of writing associated with culturally determined ways of thinking.

Despite these criticisms, applied linguists working in a number of areas, including how to teach academic or business writing to first and second language writers, may find the analysis of differences in the organization of texts (contrastive rhetoric) a productive exercise. For example, in a comparative study of English language business correspondence in Hong Kong, writers with Cantonese as a first language tended to delay and justify their requests more than those writers with English as a first language (Kong, 1998).

Cognitive Discourse Analysis

Language processing research investigates how the linguistic knowledge that is stored in the mind/brain is used in real time (as the cognitive events unfold) to produce and understand utterances.

A cognitive approach to discourse analysis is one which aims to describe language use with reference to the knowledge schemas and memory structures that are activated or constructed in language users’ minds as they engage with discourse, both in production and comprehension. The processing of discourse is a major topic in psycholinguistics, where the moment-by-moment cognitive events of language use are tracked using experimental techniques such as measurements of pause times in speaking or eye-tracking in reading. But real context is absent in such laboratory work. As a result, cognitive approaches are often viewed as philosophically, epistemologically, methodologically and even ideologically incompatible with an interest in the actual use of language by specific users in authentic contexts. Despite this, and in keeping with our belief that applied linguists are in the business of opening doors and crossing bridges in the pursuit of understanding and aiding client populations, we take seriously the view that cognitive and social processes are always co-present, and implicate each other, even if the conceptualization of the relationship between them is still confused and incomplete.

Cognitive discourse analysis is an approach which takes into account the mental representations and processes involved in the production and comprehension of discourse, including the role of socially shared knowledge stored in individuals’ long-term memory and the capacity and limitations of their short-term (working) memory.

Mental models are representations of situations in the mind which are constructed on the basis of sensory and linguistic input, general knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and intentions. They are the starting point for writing and speaking and the endpoint for listening and reading. Mental models contain far more detailed information than can be mapped onto the linguistic expressions we use to produce (encode) and comprehend (decode) them.

Conceptual blending theory looks at how the meaning of texts is comprehended in real time by a listener or reader prompted by linguistic cues to activate mental models. These models allow speaker-listeners to distinguish between different elements of a text and understand where there is a relationship (‘blending’) between these elements.

The work of Teun van Dijk provides an example of cognitive discourse analysis that demonstrates possible overlap between cognitive and social processes. He takes cognition as both personal and social, involving memory structures and mental representations such as beliefs, emotions, evaluations and goals, and links it with society, which he defines in terms of both context-specific, face-to-face interaction between individuals, and the global, social and political organization of groups and relationships between them. Van Dijk (2001) suggests that a socio-cognitive analysis can help us understand, for example, the effect of a petition against the US government’s prosecution of Microsoft for monopolistic business practices. Van Dijk argues that the writers of the text use words such as rights, freedom and individual to connect their own neo-liberal anti-interventionist stance with their readers’ mental models of positive political and social goals. An analysis of an advertisement for a political party broadcast on television during a US presidential election campaign uses conceptual blending theory to explain the mental operations involved in persuading the audience that there was a causal relationship between the actions of one of the candidates, George W. Bush, and a horrific race hate crime two years earlier (Coulson and Oakley, 2000). This kind of work, drawing on the tools of linguistics and psycholinguistics, has the potential to show how individual minds are, ultimately, the place where the meanings and effects of discourse are created, and so provides an important basis for building links with apparently irreconcilable scholarly world views, such as critical discourse analysis, discussed in section 4.3.

4.3 Social Approaches to Discourse Analysis

Conversation Analysis

Conversation analysts are interested in the organizational structure of spoken interaction, including how speakers decide when to speak in a conversation (rules of turn-taking) and how the utterances of two or more speakers are related (adjacency pairs like A: ‘How are you?’ B: ‘Fine thanks.’). As well as describing structures and looking for patterns of interaction, some analysts are also interested in how these structures relate to the ‘doing of’ social and institutional roles, politeness, intimacy, etc. What conversation analysts want to know is: why that now?

The origins of conversation analysis (CA) lie in the sociological approach to language and communication known as ethnomethodology (associated with Harold Garfinkel, 1967): the study of social order and the (actually very complex) ways in which people coordinate their everyday lives in interaction with others. CA was initially developed into a distinctive field of enquiry by, amongst others, Harvey Sacks, Emmanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson, and looks both at (usually) short segments of ordinary, mundane conversation and at the institutional forms of talk found in, for example, suicide prevention centres, group therapy sessions and classrooms. The analysis aims to show the intricate ways in which interlocutors mutually organize their talk and what these tell us about socially preferred patterns of interaction, including: turn-taking, opening and closing an interaction, introducing and changing topics, managing misunderstanding, introducing bad news, agreeing and disagreeing, eliciting a response by asking a question, and so on.

CA has been used in applied linguistics to evaluate and inform the practice of language professionals and their clients in a wide range of types of interaction, including: students doing group work at university, medical examinations, service encounters and business meetings (for accounts of the relationship between CA and applied linguistics, see Drew, 2005; Schegloff et al., 2002). For example, a study comparing the interaction of a mother and a speech therapist with a child experiencing phonetic problems (Gardner, 2005) shows how, amongst other things, the mother uses a much greater number of turns in dealing with a problem word than the therapist, with less success and with the unintended result of provoking new errors. Gardner suggests that the findings of this study could be used to demonstrate to the mother the need to reduce her number of turns per problem word, increasing the amount of positive intervention available to the child and the likelihood of progress.

Discursive Psychology

Traditionally, psychology has understood the cognitive and emotional states of individuals to be the source of interactive phenomena such as friendship, aggression and the influence of one person’s beliefs on another. Discursive psychologists, on the other hand, are interested in how (and which) ways of talking and behaving are understood by people to mean that a person is (being) friendly, aggressive, loving and so on: how we ‘do’ friendliness, for example, and what we recognize as friendliness when we see and hear it.

Who hasn’t spent time listening to another person talk and trying to work out what they ‘really’ want, or what kind of person they ‘really’ are? Cognitive traditions in psychology have tended to focus on inner mental states as the causes of what people say (and how they say it) and concentrate on talk as reflective of what a person thinks, believes, feels or wants (see the sub-section on cognitive discourse analysis on the previous page). Discursive psychology, in contrast, is interested in how people perform emotions, attitudes and beliefs in their talk, and how this performance can bring mental states into being. In other words, instead of thinking of talk as a reflection of what people are ‘really’ feeling or their ‘real’ attitudes to a topic, discursive psychologists think of talk as constituting these feelings and attitudes. For example, imagine someone you know who you believe to be shy or arrogant or happy or forgetful; a discursive psychologist would say that these are judgements you make based on how this person expresses him/herself (in specific situations in which s/he is interacting with particular people). Traditionally, psychologists have asked people about their attitudes, beliefs and emotions using surveys which aim to discover clear and stable patterns common to large groups of people. Discursive psychologists, in contrast, observe the interactional business that is performed by these accounts of attitudes etc., using recordings, transcriptions and detailed analysis of actual accounts, focusing on variability and inconsistency (Edwards and Potter, 1992; te Molder and Potter, 2005).

The topic of classroom-based additional language learners’ ‘motivation’ is an illustrative one. On the whole, motivation has traditionally been thought of by teachers and researchers as an individual phenomenon reflecting an internal mental state. A discursive psychologist, on the other hand, might focus on how students and teachers actually demonstrate, through physical activity and talk, what gets recognized as motivation, rather than asking a student whether he or she is motivated.

Discursive psychology has its disciplinary roots in the sociology of scientific knowledge (Gilbert and Mulkay, 1984) and has used analytical methods typical of conversation analysis (see Park, 2007, for a study of the construction of native and non-native speaker identities), critical discourse analysis and speech act theory (see Cameron, 2005, for an account of the role of discourse in how we experience our gender and sexuality).

Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical discourse analysts study the ways in which social power, dominance and inequality are enacted, reproduced and resisted by text and talk in social and political contexts.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a way of thinking about texts, talk and visual imagery that is sensitive to the relationship between discourse and our beliefs about ourselves, other people, relationships and things that surround us. It is committed to exposing social and political unfairness. In this context, then, critical means being interested in uncovering the role of discourse in the creation, description and solution of social problems, the acquisition and use of power and the justifications provided for change or the maintenance of the status quo. Critical discourse analysts don’t assume that the relationship between discourse and beliefs, objects, people and relationships should be taken for granted (for example, that teachers/doctors just ‘naturally’ treat students/patients in a particular way). Instead, they look in detail at the role of texts and talk in how our beliefs about our social world (for example gender roles) and physical world (for example animal welfare) come about, how our beliefs change over time and between places, who is advantaged or disadvantaged by our texts and talk, and how any disadvantage could be avoided or corrected.

The aims, theory and methods of CDA are drawn from a wide variety of sources, including sociology, literary criticism and linguistics, and are influenced by Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics (Fairclough, 1995, 2001). Topics investigated have included gender, racism, identity, political and media discourse; research designs and methods have included small-scale qualitative case studies, as well as large amounts of data collected during ethnographic fieldwork (Wodak and Meyer, 2001). In an example of how CDA can be used to investigate real-world language problems, Blommaert (2005) reports a case study of interview talk between African asylum seekers and Belgian immigration officials, showing how judgements about incoherence, irrelevance and untrustworthiness can be a function of low levels of familiarity on the part of the interviewer and/or the interviewee with the language(s) used in the interview.

One problem with the way we have chosen to organize sections 4.1 and 4.2 is that we have perhaps made the differences between the approaches look greater than they actually are. While some methods may be more homogenous in their theories and practices than others, none have rule-books and all are used in slightly different ways by different analysts at different times. The challenge for an applied linguist is to understand the assumptions about language, cognition and society that their chosen approach(es) are based on, and to have the confidence to adapt techniques to suit their own and their clients’ needs, while being transparent about these choices. We come back to this challenge in the final section of this chapter (4.4).

4.4 Themes in Contemporary Discourse Analysis

Multi-Modal Texts

It’s probably true to say that discourse analysis has tended to focus on the linguistic elements of texts. If you are reading a printed copy of this book, take a moment to look at the object you are holding; think about how the size of the font, the use of chapters, sub-headings and quotations, the glossary, the artwork, the back-cover blurb and the publishing company’s logo encourage you treat this as an academic, authoritative text, one which you can legitimately quote in your own academic writing. Think also about how quoting a text, as we have done throughout the book, alters its meaning. Take the epigraph at the very beginning of this chapter, from James Gee. You, as the reader of this chapter, have encountered Gee’s sixty-five-word text not in its original environment on page xii of the Preface to his book, but in another book (this one). This new position transforms the text into a quotation, and by implication makes it a quotable text. In its new position, the text is participating in the creation of a new piece of academic writing, a genre which is characterized by quotations. The text has, in addition, been transformed into an advertisement for the original object in which it was embedded.

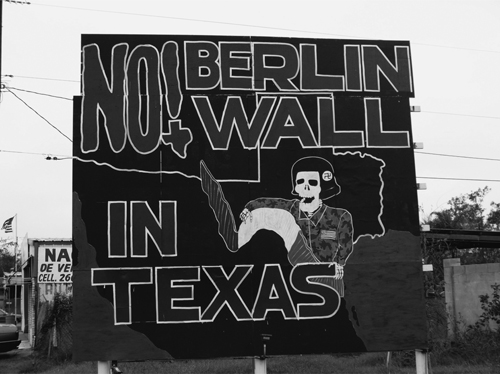

In addition to images embedded in primarily written texts like this book and the book from which our epigraph was taken, there are also image-heavy texts which may use very few words. An example is given in Figure 4.3: a multi-modal roadside sign protesting against the construction of a perimeter fence along the US–Mexico border to keep migrants from crossing illegally. Note that much of the message is conveyed by imagery rather than words (the skeleton soldier in a US military uniform and Nazi helmet and the borderline represented by a furled Mexican flag). The meaning of the sign is signalled by the combination of words, shapes, colours and its physical location (in Brownsville, Texas, USA). In an example of multi-modal discourse analysis, Piety (2004) shows how an approach to discourse that is both cognitive and social (see the sub-section on cognitive discourse analysis on p. 86) can help language professionals describe and compare different ways of doing audio description (inserting extra spoken information about the action or scene of a play, film or TV programme for the benefit of visually impaired people). Multi-modal discourse, then, can use any way of communicating meaning, including design of everyday objects, sculpture, still or moving images and sounds.

Figure 4.3 A hand-painted sign displayed on the US side of the US–Mexico border

Texts can also be oral, of course, such as conversations, service encounters and classroom discourse, although their analysis often involves transcription into written formats. Sometimes texts that reach the public via the auditory channel are first prepared in writing, such as teachers’ lesson plans and the lectures of university instructors (or at least the well prepared among them!). Some are then preserved in written texts: think of the Swiss linguist Saussure’s lectures Course in General Linguistics (1983, published posthumously by his students in 1916) or the script for a play that began with actors improvising their lines. Recent developments in communication technology favour the creation and display of multi-modal texts which combine oral and written forms of language along with music, images and other non-linguistic elements. A search of YouTube for ‘Gandhi speeches’ will provide many examples of multi-modal texts. In a typical YouTube Gandhi video, you can hear a speech, read the transcript, watch a rolling display of photos, drawings and posters of Gandhi, and perhaps listen to some lead-in music – all in one ‘text’. New forms of digital literacy are pushing us to rethink the connections between the modality and meaning of texts, particularly with respect to the possibilities for authorship and shared design that can develop in online communities.

As well as drawing on more than one semiotic system, texts can be multiply structured in other ways, including the recycling of the language and genre-specific features of other texts. A multi-modal text like the Gandhi videos mentioned above might, for example, have different ‘voices’ associated with the different modalities; in one example from YouTube, extracts from his speeches are heard over a succession of connected images relating to recent government restrictions on freedoms in the UK and USA, including press photos, newspaper headlines, movie clips, posters and text. At one point, Gandhi’s words ‘we have no secrets’ are accompanied by a camera zoom-in on the Masonic pyramid symbol on a dollar bill. At another, his words of protest against the fingerprinting of Indians in South Africa in the 1930s are heard over photos of the UK’s new ID cards, US Social Security cards and a still image of Nazi guards checking identity papers during World War II.

Bakhtin’s theory of heteroglossia suggests that a text can’t be reduced to a single, fixed, self-enclosed, ‘true’ meaning which is determined by the intention of its author. Instead, the meanings of the words in the text, and the ways in which these words are combined, are linked to conditions of cultural production and reception. What texts mean, therefore, depends on the multitude of understandings, values, social discourses, cultural codes and so on of all their potential readers and hearers.

Multiple voicing or heteroglossia is a concept associated with Mikhail Bakhtin (e.g. 1981), who suggested that all spoken and written texts echo aspects of all the other texts that have been experienced by the speaker or writer, and all the ways in which the texts have been subsequently interpreted. The job of the discourse analyst becomes one of tracing the influences and interpretations of different genres and ideologies in a text, as well as their associated values, assumptions and effects. In applied linguistics, the recognition that everyday speaking and writing require the constant stretching and twisting of communicative resources, rather than simply the reproduction of fixed, unchanging rules of language, has led analysts to focus on the creative styling in language of identities, histories and social relationships (e.g. Moss, 1989; Maybin and Swann, 2007).

Texts and Contexts

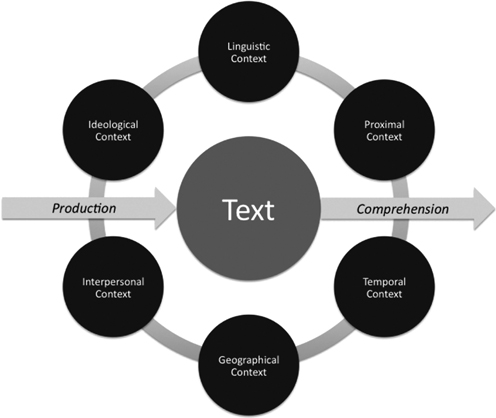

In the introduction to this chapter, we defined discourse as text that is understood to relate to context. This definition, however, raises the obvious (and difficult) question: what is context? Definitions of context abound, but they are also notoriously slippery. Minimally, context comprises the linguistic, proximal, temporal, geographical, interpersonal and ideological dimensions of the situation in which a text is produced and interpreted (Figure 4.4). Because these dimensions exist simultaneously, it’s inevitable that certain elements will be foregrounded in any given analysis, while others receive less attention.

Figure 4.4 Some dimensions of context determining the situation in which text is produced and comprehended

Praxis is educational jargon for ‘practice’ or ‘enaction’, from the Greek verb prattein, ‘to do’.

But what are these dimensional labels, if not a collection of more texts, modifying the meaning of, and being modified by, each other? James Gee (2005, p. 57) describes the relationship between text and context as ‘reflexive’; where the meaning of text and context is created by interaction between both. So how do we know which dimensions of a context are relevant? In their introduction to an edited collection of papers on language and context, Alessandro Duranti and Charles Goodwin (1992) claim that although an overarching definition of context may never be possible, it really doesn’t matter. The absence of a definitive answer to the question provides impetus for the ongoing study of language in specific contexts of use, study which asks the question: what dimensions of the situation are being made relevant here? In other words, rather than proposing that analysts decide in advance on what aspects of the context help make sense of a text, Duranti and Goodwin take an interactionist view, suggesting that analysis should focus on ‘how the participants attend to, construct, and manipulate aspects of context as a constitutive feature of the activities they are engaged in. Context is thus analyzed as an inter-actively constituted mode of praxis’ (Duranti and Goodwin, 1992, p. 9). So, while your conversation with a classmate might take place within a classroom, the classroom context (with all its typical constraints on ‘acceptable’ ways of talking and behaving) might not be made relevant in talk between pupils after the teacher has left the room, when jokes about, for example, gender difference make ‘girl’ and ‘boy’ a more noticeable aspect of the context than ‘pupil’.

Particularly salient contexts for studying discourse as praxis are those contexts in which participants come to the interaction without shared cultural norms, a common feature of settings in which applied linguists work. There are several ways of thinking about the issue, and the next sub-section, on intercultural communication, sketches some of them.

Intercultural Communication

It is possible to think about intercultural communication from a number of different points of view. A descriptive social-psychological approach (see, for example, Spencer-Oatey and Franklin, 2009) tends to assume that:

cultural and linguistic factors are inextricably linked (we communicate the way we do because of our culture);

cultural and linguistic factors are inextricably linked (we communicate the way we do because of our culture);

cultural and linguistic factors precede interaction (in contrast to the assumptions of discursive psychology, critical discourse analysis and Duranti and Goodwin’s (1992) proposal);

cultural and linguistic factors precede interaction (in contrast to the assumptions of discursive psychology, critical discourse analysis and Duranti and Goodwin’s (1992) proposal);

cultural and linguistic factors are likely to be the cause of frequent difficulties in intercultural communication.

cultural and linguistic factors are likely to be the cause of frequent difficulties in intercultural communication.

Critical approaches may be based on similar assumptions, except that communication is assumed to be the product not of culture, but of the institutions that regulate peoples’ lives, imposing their ideologies on the discourses of individual speakers (see Blommaert, 2005, for a blend of CDA and interactionist approaches). Interactionist approaches are less likely to essentialize cultural group characteristics and equate individuals with a single culture or institution. They are more likely to pay attention to the features of actual samples of discourse in an attempt to show how culture is created in interaction. Such features could include: choice of (national) language or language variety; topic management; use or avoidance of repair strategies; elicitation of preferred responses; use of phonological features to emphasize certain information; and so on (see Bremer et al., 1996, for a social-interactionist approach; and chapters in Richards and Seedhouse, 2005, for an interactionist, conversation-analytic approach).

Causality is the relationship between causes and effects. The causality of two events describes the extent to which one event happens as a result of the other.

Applied linguists are perhaps most likely to work with clients or in professional environments where the links between culture and communication are believed to be fixed and to precede specific instances of interaction, simply because the popular view of culture assumes it to be something everyone has before they start to speak (in culturally predictable ways). The direction of causality described above as social-psychological is assumed to be from culture to language; we communicate in certain ways because of our culture. This is an explanation we have frequently heard in conversations between additional language teachers (where nationality labels are used to imply cultural patterns) – along the lines of ‘The Chinese students in my class hardly ever speak, but I can’t shut the Italians up.’ Causality in the opposite direction (i.e. from language to culture) has been observed in studies of legal language, where the language spoken by an appellant is assumed to determine his or her cultural patterns of thought. In an analysis of US case law materials, Mertz (1982) shows how a policy requiring immigrants to the US to speak English is based on an assumption that the ability to understand US political concepts is dependent on fluency in English (the ‘native language’ of the law). The relationship between language and legal rights is a central concern of applied linguists, as we explore in more detail in Chapter 12.

Good applied linguists are aware that there are many possible approaches to the analysis of intercultural discourse. Moreover, they realize that specific problems can be created, and also diffused, by the very approaches that are adopted to understand them. The acknowledgement of this awareness leads us to what might seem a surprising conclusion to a discussion premised on the idea of communication problems. Intercultural communication, we suggest, is no different from communication in general. This is not to say that there are no differences between the ways in which groups of people and individuals think and behave: indeed there are. But the impact of these differences on communication can be grossly exaggerated. More important than itemizing the differences is an exploration of how these differences are used and who benefits (or loses out) when a difference is assumed. Successful communication, in our opinion, is not so much dependent on similarities or differences in language and culture, but on willingness to listen, to empathize and to negotiate. These qualities are less to do with language and more to do with attitudes and practice. To assume the inevitable existence of essential differences between individuals or groups results in the creation of many fictional barriers. To use these barriers to exclude people on the grounds of their difference is common practice, profitable for the party with the most power, and difficult or dangerous for the party with the least.

4.5 How Can Doing Discourse Analysis Help the Clients of Applied Linguists?

One of our most important jobs as applied linguists is to describe precisely how our clients’ lives are affected by language, based not on folk beliefs, but on the systematic collection and analysis of relevant evidence, central to which are language data. In some cases, individual clients will benefit from interventions designed to help them in their specific situation. In other cases, we may choose to focus on interventions that seek to bring about a fundamental shift in our clients’, and other peoples’, perceptions of their situation. These interventions include or combine attempts to effect a move from a prescriptive (deficit) perspective on language use (in which ‘non-standard’ groups and practices are seen as inferior), to a descriptive perspective which demonstrates the integrity of our clients’ use of language, or to a critical perspective which exposes discrimination against our clients, or to an interactionist perspective which attempts to show how language problems are locally constructed in specific contexts of use.

Wherever we think that solutions to a language problem might lie within an individual client and/or in the people, institutions and talk that surround them, some kind of discourse analysis is likely to be useful. At the beginning of this chapter (p. 77), we mentioned the benefits of choosing an approach that has a history of being used in your area of interest, as well as the benefits of taking an approach (and associated methods) from a different area to your own. Going back to the topic of additional language teachers’ treatment of student errors, we could, for example, look at a recently published study (which uses critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics) of how newspaper reports use language to create very specific reader responses to political events, by ‘positioning’ their readers in a certain way (Coffin and O’Halloran, 2010). A teacher could collect examples of their own and other teachers’ correction of students’ written work and, using the same approach and methods as the Coffin and O’Halloran study, consider how the language of these corrections might position students in a certain way, perhaps as novice language users, with the reduced rights to creative self-expression apportioned to the not-yet-competent.

Action research is a form of self-reflective enquiry (which may include discussion and reading) undertaken by participants in social contexts with the aim of improving their situation in some way. Action researchers often organize their activities in ongoing cycles of reflection and action.

The Coffin and O’Halloran study successfully combines two different approaches to discourse analysis: critical discourse analysis and a corpus-based approach. Combinations of approaches are another possibility when making your choice but it is important to bear in mind that some of the approaches described above are based on a range of different, sometimes contradictory, ideas about language, culture, context, identity and power. Perhaps it could be argued that, in order to fully understand an approach and the techniques associated with it, the applied linguist should aim to specialize. On the other hand, the use of multiple approaches to the analysis of what our clients say and write (and what is said and written about them) may help illuminate multiple aspects of their language problems and therefore indicate the best range of solutions. Perhaps the ideal situation is one in which applied linguists work in teams of analysts; providing ways of seeing, and avoiding prescriptions of what to see, through discussion and collaboration with fellow practitioners. Certainly, any solution we design for our clients or action we undertake on their behalf, based on discourse analysis (or any other research method), needs to be carefully evaluated as part of an ongoing cycle of observation, analysis, reflection and action, in other words an action research approach (McNiff, 2002; Burns, 2009).

We may have given the impression in this chapter that discourse analysis is the only tool that a good applied linguist needs to know how to use. Indeed, where a detailed analysis of single instances of interaction or a small collection of texts is what’s needed, discourse analysis is likely to be entirely valid and appropriate. But of course many language problems might require other, very different, kinds of analytical tools (for example spectrograms, for speech sounds: see Chapters 12 and 13). It’s also important to note that discourse analysis is not necessarily suited to situations in which we are being asked, or would like, to generalize our diagnosis or proposed solution across large populations and over time. Because discourse analysis (like other kinds of qualitative analysis) usually deals with short extracts of text or talk, it is often impossible to say whether, or how, these extracts are representative even of the client groups we are working with, never mind all similar client groups, at all times. Where such generalizations are required, we might be better off using much larger data samples and associated quantitative approaches to analysis, for example from language corpora, while reminding ourselves that even well-designed quantitative studies risk over-essentializing very complex processes of social difference or change.

It’s tempting to say that where we have the resources to collect data from large groups of people we should combine qualitative and quantitative approaches to analysis. But individual applied linguists may not have such resources, and care must be taken when combining approaches that are based on potentially incompatible ideas about language, culture and the relationship between research and practice. Again, perhaps one solution to providing the best combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches is teamwork.

As applied linguists, it is our job to be constantly aware of the opportunities and constraints of discourse as they are experienced and produced by our clients. Moreover, to adapt a phrase from the epigraph (p. 76), we must be unrelenting in our efforts to ‘think more deeply about the meanings we give [their] words’ and unrelenting in our attempts to reveal these meanings to others.

Further Reading

Coffin, C., Lillis, T. and O’Halloran, K. (eds) (2010). Applied linguistics methods: A reader. London: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2005).An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. London: Routledge.

Jaworski, A. and Coupland, N. (eds) (1999). The discourse reader. London: Routledge.

Johnstone, B. (2002). Discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.

Schiffrin, D., Tannen, D. and Hamilton, H. E. (eds) (2003).The handbook of discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.

Walsh, S. (2006). Investigating classroom discourse. London: Routledge.