How many words are there in the title to this sub-section (Words in the mind and in society) ? Is it six or seven?

How many words are there in the title to this sub-section (Words in the mind and in society) ? Is it six or seven?Chapter 11

The idea that all that work by so many different people will one day be neatly compressed into one oblong book and look as though it just fell out of a tree – that is really a wonder.

(Landau, 2001, pp. 229–230)

Lexicography, the science and practice of dictionary-making, is a vibrant field, currently experiencing rapid growth as a result of the spectacular advances in technology of the last few decades. Dictionaries are no longer fusty tomes compiled by grey-bearded Victorian enthusiasts, who pinned down words like the corpses of exotic butterflies as though desiring to embalm the language itself. Dictionary-makers these days can be pretty savvy, maybe even hip, striving to outdo each other in the authenticity, contemporaneity and accessibility of their wordware. Indeed, although lots of dictionaries are still bought in book form, they are more likely to be consulted nowadays via pre-installed desktop computer applications, websites with online look-up and hand-held devices (Li, 2005).

Dictionaries are perhaps the most popular manifestation of applied linguistic labour, found in most homes that have books and used by millions of the planet’s literate majority to solve lexical problems that stretch from language learning and translation to crossword solving and technical-report writing. How dictionaries are constructed and how they are used is therefore seen by many as a central area of applied linguistics (although once again there are many lexicographers who would not consider themselves members of the club).

Lexicography is closely associated with an area of descriptive linguistics called lexicology. In twentieth century linguistics, lexicology was largely neglected, as the emphasis shifted to phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics. But it hasn’t disappeared. As the influential British linguist M. A. K. Halliday (2004) presents it, the goal of lexicology is to produce descriptions of the words of a language, and these descriptions are then published as dictionaries. Thus, dictionary-making starts as lexicology, the study and description of a body of words, and ends as lexicography, the compilation of these descriptions into a single reference work.

Lexicology is the academic study of words: their spoken and written forms, their syntactic and morphological properties, and their meanings; in a particular language or in human language in general; both at a fixed point in history and as they change through time.

Following this logic, we start out this chapter (section 11.1) with a more theoretical discussion of the nature of words as both mental and social objects, before moving on to more applied concerns, such as the changing role of dictionaries (11.2), the variety of forms and functions they take (11.3), how they are compiled (11.4), their central role in language learning (11.5) and, finally, the involvement of technology in the lexicographic process (11.6). By the end of the chapter, you should have a keener understanding of some of the key issues in the theory and practice of lexicography and, in particular, will be able to assess potential contributions of lexicographers to the solution of a variety of applied linguistic problems, as addressed in 11.7.

11.1 Words in the Mind and in Society

Let’s start with the problem of what a word is and isn’t. Here are some questions to get the ball rolling:

How many words are there in the title to this sub-section (Words in the mind and in society) ? Is it six or seven?

How many words are there in the title to this sub-section (Words in the mind and in society) ? Is it six or seven?

Is words the same word as word?

Is words the same word as word?

Is mind the noun a different word from mind the verb (as in ‘I don’t mind if I do’)?

Is mind the noun a different word from mind the verb (as in ‘I don’t mind if I do’)?

How do we define words like in and the such that our definitions also cover the same words in ‘in the know’ or ‘in the Taj Mahal’?

How do we define words like in and the such that our definitions also cover the same words in ‘in the know’ or ‘in the Taj Mahal’?

These are not easy questions, because the concept of ‘word’ is not at all an easy one to define, despite its familiarity. In the last century, as general linguistics turned its central attention away from the description of languages as formal systems divorced from mind and society, and began to focus instead on language as mental representation and socially situated action, the old lexicological certainty about wordhood was eroded. Linguists now question the stability of the concept of word, asking among other things whether word meaning is really ‘part’ of the word, or is found in social usage or in the mind’s conceptual memory; whether words have single canonical forms or belong to fuzzy, overlapping sets shared between speakers and situations; whether words have any limits on their length or internal structure; whether they can be counted, and so whether vocabularies can be quantified (Hall, 2005, ch. 3).

In general linguistics, some (e.g. Hall, 2005, p. 83) claim that words as single entities don’t really exist … But applied linguists can’t afford to wallow in such epistemological luxury. As we explained in Chapter 1, they need to mediate between theory and practice, between the inherent uncertainty of scientific hypothesis-testing and the ‘faith-based’ certainty of folk belief. In other words, applied linguists need a working definition of ‘word’ so they can help solve non-linguists’ problems with what they think of as words. For example:

experts in language teaching need to connect with learners’ conceptions of vocabulary and how it is learned, despite the attractiveness and plausibility of more radical, research-based lexical approaches (e.g. Willis, 1990; Lewis, 1993);

experts in language teaching need to connect with learners’ conceptions of vocabulary and how it is learned, despite the attractiveness and plausibility of more radical, research-based lexical approaches (e.g. Willis, 1990; Lewis, 1993);

translators often need to work with the conventional notion of translation equivalents at the word level, even if psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic research suggests that absolute translation equivalents don’t exist (see Chapter 10);

translators often need to work with the conventional notion of translation equivalents at the word level, even if psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic research suggests that absolute translation equivalents don’t exist (see Chapter 10);

language pathologists need to deal with the real problems people with aphasia have with word-finding in ways which will be meaningful to both patients and their families (see Chapter 13).

language pathologists need to deal with the real problems people with aphasia have with word-finding in ways which will be meaningful to both patients and their families (see Chapter 13).

Perhaps foremost among the applied linguists, lexicographers have to embrace a working definition of ‘word’, since their task is to collect, analyse and codify what language users treat as words, so that those users can have a permanent record of them, as reference and guide.

In order to operationalize the notion of word for lexicography in a way which is at least compatible with the complexities of the linguistic view, we should probably start by acknowledging the dual mental and social existence of words. These are concomitant and complementary realities: words must be both mental and social in order to do their job. Let’s take each in turn.

Words as Mental Networks

First, from the psycholinguistic perspective, words are interconnected memory representations in individual minds, linking together a mass of information in addition to form and core meaning. Here are some of the less intuitive bits:

fragments of grammar (parts of speech, kinds of complement, etc. – for example that hold is a ‘transitive verb’ and that furniture is a non-count noun in some speakers’ minds and a count noun in others’);

fragments of grammar (parts of speech, kinds of complement, etc. – for example that hold is a ‘transitive verb’ and that furniture is a non-count noun in some speakers’ minds and a count noun in others’);

pointers to lexical phrases and collocations in which the word form habitually participates, like take in the entry for umbrage;

pointers to lexical phrases and collocations in which the word form habitually participates, like take in the entry for umbrage;

Lexical phrases are chunks of language consisting of strings of words which are regularly spoken, signed and/or written together, like Take care! or To whom it may concern

Collocations are frequently occurring sequences of words. You can search for sample collocations for words that you input at The Collins WordbanksOnline English Corpus

activation levels (how fast the form can be accessed in memory when you need it for speaking, listening, reading or writing), determined by frequency and recency of usage (for example high frequency rain versus low frequency precipitation);

activation levels (how fast the form can be accessed in memory when you need it for speaking, listening, reading or writing), determined by frequency and recency of usage (for example high frequency rain versus low frequency precipitation);

Word frequency is an estimation of the regularity with which a word occurs in speech and/or writing, normally calculated on the basis of large samples of language, such as those provided by corpora. The Compleat Lexical Tutor , a suite of tools from Tom Cobb at the Université du Québec à Montréal, contains a frequency profiler for texts you can input yourself, and is available on the companion website.

indices of pragmatic force, situational appropriateness, sociocultural value and other connotations of usage, for example problem versus issue versus dilemma.

indices of pragmatic force, situational appropriateness, sociocultural value and other connotations of usage, for example problem versus issue versus dilemma.

From this perspective, words are not neat pairings of forms and meanings (like the two sides of a coin in the famous metaphor of the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure); rather they are fuzzy sets of disparate kinds of knowledge connected up in multifarious ways. Here is a tiny selection of some of the causes of blurred lexical boundaries:

There are, at least in English, multiple homonyms, either homophones like red (the colour) and the past tense of read, represented as a single phonological word form connected to two different spellings and meanings, or homographs like lead (the verb) and lead (the metal), a single orthographic word form with two different pronunciations and meanings.

There are, at least in English, multiple homonyms, either homophones like red (the colour) and the past tense of read, represented as a single phonological word form connected to two different spellings and meanings, or homographs like lead (the verb) and lead (the metal), a single orthographic word form with two different pronunciations and meanings.

Homonyms are two or more words that are pronounced and/or written the same way (e.g. site, sight, and cite; a sycophantic bow to the Queen vs. a bow in your hair; case as ‘baggage’ and ‘instance’).

Some words with purely grammatical functions (like the of in ‘think of’ or the to in ‘I want to be alone’) have form and part of speech but no meaning.

Some words with purely grammatical functions (like the of in ‘think of’ or the to in ‘I want to be alone’) have form and part of speech but no meaning.

Many (perhaps most) word forms express more than one related meaning, a phenomenon known as polysemy. For example, get as in get old (‘become’), get a new car (‘obtain’), get talking (‘begin gradually’), get the joke (‘understand’), etc.

Many (perhaps most) word forms express more than one related meaning, a phenomenon known as polysemy. For example, get as in get old (‘become’), get a new car (‘obtain’), get talking (‘begin gradually’), get the joke (‘understand’), etc.

Polysemy refers to the very frequent situation in which a single word form does many semantic jobs, expressing a series of related meanings. There will be a core concept underlying the several meanings, but it’s normally context which provides the specific sense (e.g. run in Tears ran down his face and A shuttle runs from the airport every hour).

Some (potential) word meanings have no single word form to express them: these are lexical gaps, like the absence in English of a single word for ‘five years’ (where Spanish has lustro) or for ‘aunts and uncles’ (where Spanish has tíos). Douglas Adams, creator of the Babel fish (see Chapter 10), also wrote (with John Lloyd) The Meaning of Liff, a ‘dictionary of things that there aren’t any words for yet’, available in its entirety online (Adams and Lloyd, 1983).

Some (potential) word meanings have no single word form to express them: these are lexical gaps, like the absence in English of a single word for ‘five years’ (where Spanish has lustro) or for ‘aunts and uncles’ (where Spanish has tíos). Douglas Adams, creator of the Babel fish (see Chapter 10), also wrote (with John Lloyd) The Meaning of Liff, a ‘dictionary of things that there aren’t any words for yet’, available in its entirety online (Adams and Lloyd, 1983).

Lexical gaps occur in a language when it lacks a word for a concept (which may be expressed lexically in another language).

And the list could go on (see the companion website for the full version). The upshot is that words seen as entries in the mental lexicon are not unitary notions. In lexicography, on the other hand, their waywardness must be acknowledged but also tamed, if dictionaries are to serve their users in an effective manner.

The mental lexicon is the component of memory where we store the vocabulary we know and use. We access its entries at lightning speed every time we speak, listen, sign, read or write.

Words in Social Use

Now we turn to words as social objects, because they don’t figure only in lexical memory, but also out there in groups, identities and events. Sociolinguists, like psycholinguists, see words as inherently variable, hard to pin down in lexicographical collections. From the social perspective their variability is seen in the situations in which they are used and the identities of the groups who use them, rather than in the intricacies of their mental storage. As we have seen again and again, language doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It is always contextually mediated. Word forms and their core meanings are not on their own sufficient to communicate the rich kinds of meaning that we human beings need in order to negotiate our daily lives. Much of word meaning is actually derived from contexts of use, and these are infinitely variable and can’t be recorded in the finite limits of dictionaries. Furthermore, some pronunciations of word forms, or the forms themselves, are associated with particular groups of speakers. Others carry different meanings when used by certain speakers in certain social contexts.

Take the following text: ‘I’ve done a lot of drugs in my time, but these days if I do a load of charlie or pills on Friday, I’m monged out till about Wednesday and I can’t think straight while making a tune’ (from Q magazine, 2002, cited in Dent, 2003, p. 77). The verb do when used with drugs means the same as take, but with the additional meaning component ‘regularly’, and for recreational rather than medicinal purposes. But the difference is not just a semantic one. ‘Doing’ drugs is associated also with an informal social register: it will not be used in medical textbooks or legal codes, for example. The word form charlie will be known by most speakers probably as a proper name, but here is an insider term for cocaine. Then there is the phrase ‘monged out’, which appeared in UK street slang in the last decade and means ‘under the influence of drink or drugs’. It is not yet in most dictionaries, although Grant Barrett’s online dictionary of ‘words from the fringes of English’ (Barrett, 2006) lists it as coming from the noun monging, dating from as far back as 1992. Finally, consider the verb make , used here with ‘a tune’ where the more specific verb compose might be expected. The verb is used by a musician, quoted in a rock music magazine, so it may be that ‘making tunes’ is favoured over ‘composing tunes’ because of its less pretentious, more ‘hip’ tone.

The sociolinguist will thus see words as functions of social contexts, acquiring meaning from context (doing drugs), marking group identities (charlie), reflecting social trends (monged out) and marking speaker roles and attitudes (making tunes).

All this causes potential problems for dictionary-makers, who must present a static, inevitably context-reduced record of what is a dynamic social phenomenon.

Capturing Words

If words represent a moving target, both psychologically and socially, how are the lexicographers to capture them? Here are a few initial criteria, which we’ll develop as the chapter progresses:

restricting meanings to core senses or frequently attested senses;

restricting meanings to core senses or frequently attested senses; providing contextual elements only when they recur with frequency;

providing contextual elements only when they recur with frequency; limiting information about pronunciation and spelling to one or at most two varieties;

limiting information about pronunciation and spelling to one or at most two varieties; packaging the lexical spaghetti of homophones, polysemes and the like into mouth-sized spoonfuls (called entries).

packaging the lexical spaghetti of homophones, polysemes and the like into mouth-sized spoonfuls (called entries).The first four criteria, relatively technical issues, can be put off for later. But we really can’t postpone discussion of the last criterion, which still grabs headlines on a regular basis and seems to annoy clients of applied linguistics (in this case, the dictionary users) as much as any other area we cover in this book.

11.2 Authority or Record?

In The Devil’s Dictionary (2003 [1911]), the US writer Ambrose Bierce starts off the entry for lexicographer as follows:

LEXICOGRAPHER, n.

A pestilent fellow who, under the pretense of recording some particular stage in the development of a language, does what he can to arrest its growth, stiffen its flexibility and mechanize its methods. For your lexicographer, having written his dictionary, comes to be considered ‘as one having authority,‘ whereas his function is only to make a record, not to give a law.

(Bierce, 2003 [1911], p. 178)

Bierce’s view looks like quite an enlightened one for the time, since he appears to be arguing for descriptivism over prescriptivism (‘a record, not … a law’). But he is still deeply conservative at heart, worrying later in the same entry about linguistic ‘impoverishment’ and ‘decay’ and extolling the ‘golden prime and high noon of English speech; when from the lips of the great Elizabethans fell words that made their own meaning and carried it in their very sound’ (Beirce, 2003 [1911], p. 179). The idea that the lexicographer should provide a full and faithful record of English speech as it falls from the lips of uneducated labourers, unruly teenagers, rural dialect users, ‘non-native’ speakers, gang members and others who may not aspire to the epithet ‘great’ would probably have appalled him.

Almost a century later, many educated speakers in countries with long literacy traditions still succumb to the ‘spell’ of language (Hall, 2005), allowing the monolithic myth of a single correct version of each language to mould our attitudes to vocabulary. When we exclaim, ‘But it isn’t in the dictionary!’ to affirm that some word or other ‘doesn’t exist’, we continue to ‘invest [lexicographers] with judicial power’. As Carter (1998, p. 151) puts it, ‘the dictionary is a trusted and respected repository of facts about a language. And an important part of its good image is that it has institutional authority’. But although ordinary speakers insist on treating dictionaries as repositories of the one true version of the language, few English language lexicographers would now feel comfortable with the role of custodian of linguistic purity.

The publication of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary in the US in 1961 marked a watershed for lexicography, with its ‘permissive’ (i.e. descriptivist) stance. It included so-called ‘non-standard’ forms like ain’t, groovy and irregardless, and cited as sources people like Elizabeth Taylor and Bob Hope as well as William Shakespeare and Henry James. This was a major shift from the original intention of Noah Webster himself. In his An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), Webster patriotically set out to codify the English of the United States as an independent variety, distinct from British English. Although he had no wish to hinder the natural growth of the language and welcomed lexical innovation, he still had strong ideas about what was acceptable and what was not, omitting ‘indelicate’ words like turd and fart, which had appeared in Samuel Johnson’s and other more liberal dictionaries of the previous century (Landau, 2001, p. 69).

The reception by the critics and the language mavens was – perhaps unsurprisingly for the times – extremely negative. Finegan (1980, pp. 116–128) recounts the ‘hysterical alarm’ with which the Third was met, citing review articles with titles like ‘The Death of Meaning’. The main criticisms were that it was too ‘democratic’ and ‘permissive’, and – interestingly for us – that it ‘was thought a ‘hostage’ of the new science [of linguistics]’, which in its objective, non-judgemental approach to language variation was perceived as promoting linguistic anarchy. The American Heritage publishing company was so outraged that it sought to buy Merriam-Webster in order to suppress the Third. Failing in its attempt, it published its own in 1969: The American Heritage Dictionary (AHD). The AHD adopted what Finegan and Besnier (1989, p. 500) call a ‘custodial’ position, like that of the national language academies, which ‘has limited respect for what even reputable writers do; instead it places a premium on what such writers and others (including the prescriptivists themselves) say ought to be done’. The arbiters were a usage panel of the great and good, including ‘distinguished writers, critics, historians, editors and journalists, poets, anthropologists, professors of English and journalism, even several United States senators’ (Finegan, 1980, p. 136). Ironically, given their implicit desire to constitute the definitive authority on lexical usage, the panel agreed unanimously on only one of the more than 200 cases they were called upon to adjudicate.

Let’s take a look at the corresponding sample entries for the verb finalize in the Third and AHD, respectively:

fi•nal•ize […] vb -ed/-ing/-s vt : to put in final or finished form : finish, complete, close <soon my conclusions will be finalized –D.D. Eisenhower> <the couple ~ plans to marry at once –S. J. Perelman> <empowered to … ~ the deal –James Joseph> : give final approval to <the list has not been finalized by the deputy, but it won’t be changed now –Robertson Davies> <ties up the day’s loose ends, finalizing the papers prepared and presented by his staff –Newsweek> ~ vi : to bring something to completion <if we don’t ~ tonight, those two … will get suspicious and sell to someone else –I.L. Idriess>.

(Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, 1961)

fi•nal•ize […] tr.v. –ized, -izing, -izes. To put into final form; to complete Usage: Finalize is closely associated with the language of bureaucracy, in the minds of many careful writers and speakers, and is consequently avoided by them. The example finalize plans for a class reunion is termed unacceptable by 90 per cent of the Usage Panel. In most such examples a preferable choice is possible from among complete, conclude, make final, and put in final form.

(The American Heritage Dictionary, 1969)

Note how the Third simply lays out the series of meanings illustrated by their citation evidence, using definitions, near-synonyms and examples, blithely listing the verb as both transitive and intransitive, and allowing social contexts of use to emerge from sentence context. The AHD’s approach is the polar opposite, providing only one definition, for the transitive verb only, and a lengthy usage section characterized by implicit social judgements about groups of speakers and explicit advice regarding the word itself and how to deal with it: ‘careful’ users associate the word with bureaucracy, and so ‘consequently’ they avoid it; the Usage Panel explicitly disapproves (with 90 per cent of them finding it unacceptable!), so ‘preferable’ alternatives are offered. The contrast between the approaches could not be sharper.

So what has changed since this ‘war of words’ of the 1960s? One thing is certain: linguistics has not had much of an impact on the general public’s belief in the authority of dictionaries. But applied linguistics, including lexicography, has matured, and language professionals now know better than to ignore their clients’ views by practising naïve ‘linguistics applied’ (cf. Chapter 1). Much contemporary lexicography manages both to remain true to the linguistic view of language and also to satisfy clients’ perceived need for guidance, by recording all common usage while at the same time indicating ‘appropriate’ contexts of that usage. So, for example, the Merriam-Webster Online now has a usage note for finalize, which tells us that the verb ‘is most frequently used in government and business dealings; it usually is not found in belles-lettres’. It is still deemed unacceptable by over one-quarter of the AHD Fourth Edition’s Usage Panel, however (revealing that not all lexicographers are equally hip!).

Significantly, the applied linguistic perspective has not sought to eradicate all vestiges of prescriptivism in contemporary lexicography. As we saw in Chapters 2 and 6, a uniform written variety of the language may still be defended, and is in fact assumed in all general purpose dictionaries, with variants clearly labelled as such. Take for example the social conventions of spelling. The FAQ (frequently asked questions) section of the OED’s AskOxford website states the following:

Most lexicographers are good spellers, if only owing to lots of practice. Lexicographers take the same view of language as other linguists. They know that language use varies widely in space and time, and they spend much of their time charting its changes through history. They are therefore not shocked or surprised to encounter variation in spelling. At the same time, they recognize that there is a standard set of conventional spelling rules to which we all mostly conform, and which assist good communication.

(AskOxford, 2010)

Furthermore, you may recall from Chapter 5that dictionaries play an important role in codifying the vocabulary in newly literate languages and languages in the process of revitalization through literacy, as a tool of both corpus and status planning. This applied linguistics enterprise is essentially prescriptivist: providing a ‘standard’ list of word forms and meanings which may be used in official documents and other national forums, both oral and written. Dictionary projects in language planning are also often charged with formulating terminology to serve new cultural, technological, scientific and economic challenges. The Maori Language Commission, charged by legislation from 1987 to promote the use of Maori in New Zealand, sees lexical expansion as a major language planning goal. Te Matatiki, a monolingual dictionary, is an important part of that process, and the prescriptivist component is confirmed on the Commission’s website in a reference to new words being ‘validated by the Commission’ (Maori Language Commission, n.d., emphasis ours).

In groups of users which are already literate in at least one majority language, the publication of a dictionary to preserve a minority language may actually backfire, especially when applied linguistics expertise is not sought. Liddicoat (2000, p. 428) reports that a grass-roots dictionary project for Jersey Norman French (JNF) has ‘actually given an impetus to language shift rather than to language maintenance’, because the orthographic codification of what was a collection of oral varieties led to feelings of linguistic inadequacy, especially among its younger speakers. He continues:

The development of a dictionary, with a standardised spelling system, is not an ideologically neutral act … The presentation of an authoritative, normative, but unexplained orthographic system had an ecological impact. Native speakers of JNF, who are literate in at least one language [English and/or French], now express a lack of proficiency in JNF because they do not know how to write the language – they have become illiterate.

(Liddicoat, 2000, p. 428)

This case illustrates once more our contention that applied linguistics cannot operate in a social vacuum: lexicography affects language ecology, and so must be conducted with foresight, sensitivity and extensive knowledge of associated issues in general and applied linguistics.

In some of the world’s more ‘powerful’ language communities, dictionaries may play a much more overtly prescriptivist role in the language management process, responding to the spread of English and the perceived ‘sullying’ of the national tongue through loan words. As Finegan and Besnier point out in the passage quoted on p. 255, the dictionaries of the revered national language academies are often the major instruments in this endeavour. The academies consciously adopt a clearly ideological lexicographical policy, though their ecological impact on speakers’ usage has been negligible. The Académie Française was founded in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, as part of broad efforts to centralize royal power so as to counter internal and external threats. In the face of new perceived threats from English, the Academy clearly affirms that the purpose of its dictionary is to ‘fixe l’usage de la langue’ (fix language usage) (Académie Française, n.d.). Other academies take their lead from the French. The Spanish Royal Academy, for example, was founded in 1713 with the motto ‘Limpia, fija y da esplendor’ (cleanse, fix and make resplendent). The stated aim of its dictionary is to ‘confer normative value in the entire Spanish-speaking world’ (Real Academia Española, 2006, our translation).

Using dictionaries as instruments of ‘lexical cleansing’ is not restricted to the wealthy, former imperial powers of Europe. Smaller nations, hosting smaller languages, asserted their postcolonial identities also through the exclusion of foreign words. According to Spolsky (2004, pp. 37–38), the Iranian Academy of Language proposed 35,000 new Persian words to replace foreign ones before the revolution of 1979, and after the Soviet occupation Estonia published 100 terminological dictionaries to counteract the pressure from Russian. And Quechua, an Indigenous language spoken by millions in Peru and Ecuador and in the Andean regions of Bolivia and Colombia, has been subject to attempts to ‘fix and cleanse’ by the Cusco-based Academy of the Quechua Language (Hornberger and King, 1998; Marr, 1999).

Dictionaries can, of course, also be used as tools of resistance to prescriptivism. The online Coxford Singlish Dictionary, for example, provides a satirical antidote to the Singapore government-sponsored ‘Good English Campaign’, which, you may recall from Chapter 5, attempts to stifle the local, indigenized variety of English (Coxford Singlish Dictionary, n.d.). But even in postcolonial World Englishes contexts where one might expect a more radical, anti-prescriptivist attitude, the Inner Circle (Anglo native-speaker) models are being replaced in the Outer Circle by new norms determined by local ‘educated’ usage. Kachru and Smith state the following about Asian ELT professionals:

[They] are used to norms presented in [American and British] dictionaries and as mature users of the language, they rely on their prior experience. However, they are also aware of the local norms of usage and are familiar with words and expressions that even highly educated people in their own community use regularly. These local words and expressions, of course, are not listed in the dictionaries they are familiar with. The dilemma that they face is whether to consider the local items legitimate and acceptable in educated English.

(Kachru and Smith, 2008, p. 105, emphasis ours)

These authors provide references to various dictionary projects for Englishes of the Outer and Expanding Circles (Kachru and Smith, 2008, p. 103), highlighting the success of the ongoing Macquarie Dictionary project for South and Southeast Asia. But the main criteria they cite for inclusion of items are: (1) occurrence and frequency in the corpus being assembled; and (2) ‘opinion of local experts with regard to the item’s status, i.e. is it used in “standard” regional English – both formal and informal – or is it restricted to informal colloquial language use only?’ (Kachru and Smith, 2008, p. 110). There are clear echoes of the American Heritage approach here. But while linguistic hegemony exists at global levels – US and UK standard Englishes globally, Russian in the ex-USSR, Spanish in Latin America – lexicographical prescriptivism is an inevitable factor in local language planning.

11.3 Uses and Types Of Dictionaries

When asked to name a dictionary, English speakers in the UK will probably mention the Oxford, and in the US Webster’s. French speakers will go for Robert, Larousse or that of the Académie Française; German speakers might plump for Duden; and most Spanish speakers will unquestioningly commend that of the Real Academia. When prompted to tell you what they use these dictionaries for, they will in all likelihood tell you that they use them to look up the meaning or spelling of a word they’re unsure of. But there are many thousands of dictionaries in the world’s major languages, presenting different kinds of words in many different ways – and for many different purposes. Amazon.com lists over 28,000 titles in its category of dictionaries and thesauri.

Lexicographical typologies have been proposed which classify dictionaries into a whole host of types, defined by anything from age of user to number of words included. Landau (2001) mentions an extensive range. In the following sub-sections we explore some of the huge variety of formats and objectives which dictionaries adopt, starting with issues of access and structure, and then moving on to specialized lexicographical content.

Differences in Macrostructure

A distinction is drawn in lexicography between a dictionary’s microstructure, the internal organization of individual word entries, and its macrostructure, the organization of the whole work. We’ll concentrate on the latter here, leaving the former until later. Oxford University Press publishes over 200 titles with the word dictionary in the title, but many of them, such as A Dictionary of Chemistry or the Oxford Dictionary of Dance are actually encyclopaedias, reference works in which concepts are the focus, rather than the words that label them. Encyclopaedias closely resemble dictionaries because our principal means of transmitting information about concepts is through the words associated with them. Although pictures can help immensely, we still have no conventional method for ordering visual information, thus making word-based, alphabetically ordered entries the current standard for easy access. Dictionaries focus on words, even though it’s often the concept conveyed by the word that dictionary users are looking for: if you come across a word form you don’t recognize (e.g. metamer), or one that you do but whose exact meaning you don’t know or recall (e.g. polymer), you may well reach for your dictionary. However, if you want to know more about chlorophyll, the novels of Naguib Mahfouz or China’s Qin Dynasty you’re more likely to consult Wikipedia on the internet or a print encyclopaedia in your local library.

The internal organization of a dictionary’s entries is called its microstructure. The way the whole dictionary is put together (with words listed in alphabetical order, for example) is called the macrostructure.

What happens if you have the concept more or less clear in your mind but it’s the word’s form which escapes you? Say the form is polymer (you need it because you’re telling a neighbour about the anti-corrosive polymer coating on your new car), but it’s not even on the tip of your tongue. You can’t use a traditional dictionary or encyclopaedia to find the word because the word form is the access point and that’s precisely the information you lack. You might, however, have in mind a related but more general word, such as chemical. The dictionary entry for chemical is unlikely to mention the word polymer, but a thesaurus entry will. Although the word thesaurus is sometimes used to describe other kinds of dictionary, most people now use it to refer to the kind of work first compiled by the French lexicographer Peter Mark Roget, published in 1852 and still perhaps the most widely used work of this kind. It contains over a quarter of a million terms, organized thematically into over a thousand ‘idea categories’, which themselves are grouped into eight conceptual ‘classes’: abstract relations, space, physics, matter, sensation, intellect, volition and affections.

To find the word polymer, for example, the user starts by looking up a semantically related word in the alphabetical index. Thus, the first reference in the index entry for chemical points you to section 379.1 in the main list, the first of thirteen sub-categories of the category ‘chemicals’, part of the sub-class ‘matter in general’, in the fourth idea class, namely ‘matter’. There, you read:

nouns chemical, chem(o)-or chemi-, chemic(o)-; organic chemical, biochemical, inorganic chemical; fine chemicals, heavy chemicals; element, chemical element; radical; ion, anion, cation; atom 326.4,21; molecule, macromolecule; compound; isomer, pseudoisomer, stereoisomer, diastereoisomer, enantiomer, enantiomorph, alloisomer, chromoisomer, metamer, polymer, copolymer, interpolymer.

(Roget’s Thesaurus)

Note that no meanings are indicated, although terms closer in meaning are grouped between semicolons and more general terms appear in boldface.

A thesaurus like Roget’s helps users not only to find a word form for a known concept, but also to choose alternative word forms for aesthetic reasons (hence the reference to ‘literary composition’ in Roget’s original title) or for the expression of finer meaning distinctions or for better contextual ‘fit’ with the text being written. In this sense, a thesaurus resembles a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms, which is like a regular dictionary but lists words with close meanings and opposing meanings, rather than giving definitions or illustrating usage. Take the Collins Paperback Thesaurus in A-to-Z Form, to be found on many bookshelves; this is more a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms than a thesaurus in the sense of Roget’s. In the latter, the category ‘conciseness’ is found between ‘plain speech’ and ‘diffuseness’, but in the former the entry for concise appears between the semantically unrelated conciliatory and conclave. So the Collins thesaurus differs from Roget’s in both its macrostructure and microstructure. The alphabetical arrangement of a synonym and antonym dictionary provides one-step rather than two-step access to entries, and the entries themselves contain possible substitutes for the headword as well as opposite meanings, rather than all associated words.

A further, rather uncommon, kind of macrostructure is that followed by rhyming dictionaries. In this type, the focus is exclusively on the word form, and meaning is irrelevant. Although rhyming dictionaries will principally be of use to poets or songsters who use rhyming couplets, they are also of use to linguists, when they need to find lists of words which all share the same suffix, for example. Of course, technological advances are making macrostructure a dynamic rather than a fixed dimension of dictionaries. So, for example, you can find rhymes, homophones, synonyms and polysemes (even pictures!) all through the same search engine at rhymezone.com, and you can get lists of words all ending with the same letter sequences, along with definitions and translations, at onelook.com. (See section 11.6 for more on technology.)

A rhyming dictionary is a dictionary organized according to the end of the word rather than the beginning. Some use spelling as the organizing principle (so sew is near dew), but the best use sound (so sew is near dough).

Finally, there is an expanding range of dictionaries published for deaf and blind users, client areas often neglected in lexicography (although Hartmann [2001, p. 73] acknowledges the former). For ASL users, the Gallaudet Dictionary of American Sign Language (with DVD; Valli, 2005) is the biggest, containing over 3,000 signs and English translations. Brien’s (1992) dictionary, using photographs and including extensive grammatical information, remains the most complete for British Sign Language. For the blind, Braille dictionaries are costly to produce and remarkably unwieldy. Since Braille takes up over three times the space of printed letters, a college dictionary using this alphabet can run to over seventy volumes (Hartz, 2000)! For those with residual vision there are large print dictionaries, such as Oxford’s, which covers over 90,000 words and was designed with advice from the UK’s Royal National Institute for Blind People. More common now, however, are speaking dictionaries such as those produced by Franklin Electronic Publishers, which deliver the contents of Merriam-Webster dictionaries in the spoken modality.

Specialized Dictionaries

The dictionary types described in the previous pages respond to different user needs by adapting access route and macrostructure, but their coverage of words is not restricted to a particular usage domain, oral variety or genre of discourse. Some dictionaries are designed for use by a subset of the speech community, defined by age, profession, language proficiency, cultural identity or other group membership. Examples include second language learners’ and children’s dictionaries (which we look at in greater detail in section 11.5) and dialect dictionaries.

Still others are designed for any social group, but specialize in some subset of a language’s vocabulary. Dictionaries of slang, for example, record the informal words and phrases associated with particular subcultures (normally ‘minority’ subcultures like teenagers, gangs or gay people) or simply with ‘non-standard’ usage which goes beyond regional or social dialect (especially items relating to sex and sexuality, drugs and ‘embarrassing’ bodily functions). Such dictionaries provide data for social historians, sociolinguists and others, but are perhaps mostly browsed for entertainment by general readers. Technical and professional dictionaries, on the other hand, contain the jargon associated with the concepts, processes, theories and practices of, say, electrical engineers, horticulturalists or psycholinguists. Jargon dictionaries also exist for other realms of human activity, from football to folk music, web-surfing to wine-tasting. Such works may be consulted by members of the associated community or group, in order to ensure consistent usage and thus maintain group cohesion, as well as by outsiders interested in cracking the users’ linguistic code.

Another important type of dictionary is the bilingual (or, less common, the multilingual) dictionary. Users of such dictionaries stretch all the way from beginning learners at one extreme to professional translators at the other (as we saw in Chapters 9 and 10). Bilingual and multilingual dictionaries are often also used as tools of language policy and planning, in order to provide bridging points between speakers and texts operating in different national languages. Afrilingo, for example, is a translation software package which incorporates a dictionary of over 3,000 translation equivalents in the eleven official languages of South Africa (Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga). It is being co-sponsored by the government’s Pan South African Language Board, to complement a more ambitious project to compile monolingual dictionaries for each language (PanSALB, 2009a).

In the compilation of bilingual and multilingual dictionaries the problem of translation equivalence we came across in Chapter 10must be met head-on. Whereas in translation, more or less precise equivalents may be selected so as to render the specific contextualized meaning (or may be avoided altogether in ‘freer’ translations), in lexicography the equivalents must be of general application, because once recorded in print they become fixed, codified, decontextualized. The need for example sentences is thus paramount, especially for learners, as we’ll see in further detail in section 11.5.

In this section we’ve seen examples of various types of dictionary, designed for different users with different purposes. And yet they’re not so different from each other in structure, and all share a common process of compilation, as we’ll see in section 11.4, which takes a look at the complex process of dictionary-making, from initial plans to final production.

11.4 Dictionary Compilation

Compiling a dictionary used to take a very long time. The OED saga, for example, was initiated by the Philological Society of London in 1857, but the last volume of the first edition didn’t appear until 1928, over seventy years later. Advances in technology over the past few decades have sped up the glacial flow of earlier lexicographical practice, but still the path from inception to publication is a slow one. The French Academy’s website (Académie Française, n.d.), for example, reveals that the entries corresponding to the second volume of the ninth edition of their magnum opus were completed according to a rather unhurried schedule, as shown below:

fatigable à filon, n°44, 26–5–1994

filoselle à formation, n°36, 28–3–1995

forme à frontignan, n°72, 8–8–1995

frontispice à gendarmerie, n°1, 16–1–1996

…

parfum à patte, n°10, 4–10–2006

patté à périodiquement, n° 3, 21–3–2007

périoste à piécette, n°16, 26–10–2007

pied à plébéien, n°13, 24–9–2008

That’s less than one letter of the alphabet per year, indicating that even with modern tools lexicography remains a lengthy process.

What takes so long? Well, to a certain extent this will depend on the type of dictionary being written (see section 11.3), and this, in turn, will normally depend on an identified demand or need. But most dictionary projects will pass through a series of seven cascading (rather than discrete) stages, as depicted in Figure 11.1. As in all complex tasks, the desired outcomes and the appropriate inputs and procedures required to achieve them must be planned. The final outcome is, of course, the production of the dictionary, be it in paper and ink or LCD and pixels. In between come the core phases of the lexicographical process: (1) collection of words and contexts of their use; (2) selection of the words to be included; (3) construction of the entries in which the words will appear, i.e. microstructure; and (4) their arrangement together in the dictionary, i.e. macrostructure (cf. Zgusta, 1971). The seventh stage in Figure 11.1 is the all-important and never-ending revision stage, as the dictionary-makers constantly try to keep up to date with the hurtling dynamism of the language.

Figure 11.1 The major stages of dictionary-making

The arrows in the diagram reflect the fact that these stages may overlap and interact with each other. For example, each stage must be planned, including revision, and each stage must be revised, including planning.

Planning

Market research will probably precede other kinds of planning. Lexicography is unique in applied linguistics in that the ultimate objective is, almost always, the design of a commercial product. Aside from the most well-known titles, dictionaries have not traditionally had very high profit margins, although technology is changing this (the licensing of digital rights to the AHD, for example, has made millions for its owner, the Houghton Mifflin Company, over the past few years). Unlike most other kinds of books, dictionaries cost a lot of money early in the editorial process and their actual production can be relatively cheap. Hence, although publishers don’t always require that their lexicographers research the market directly, they will insist from the outset that the scholars have clearly identified future users’ preferences and requirements.

Knowledge of their clients will assist lexicographers in making decisions about the size and scope of the product, the time frame for compilation, and the resources needed, such as the design of database systems (where increasingly they will work alongside software engineers). Such knowledge will also allow them to plan the word lists themselves, locate the best sources for definitions and examples, determine policy on the amount and type of guidance on usage, and decide on layout and conventions of presentation. A pioneer in the employment of user research was the lexicographer Clarence Barnhart, who applied a systematic questionnaire to US college teachers almost half a century ago to establish students’ preferences for different kinds of information included in college dictionary entries (Hartmann, 2001, pp. 81–82). (Perhaps unsurprisingly, he found that students used dictionaries most to check spelling and meaning, and were least concerned with etymology.)

Collection and Selection

But before resolving what to put in each entry – for example whether or not to include etymologies – one must decide which words to give entries for in the first place. Words must be collected, and then a subset selected for inclusion. Barnhart pointed out that if a project for a college dictionary did not establish limits on the number of words before compilation, the estimated page length would be entirely used up before the letter E was reached (Landau, 2001, p. 357). Landau (2001, p. 360) reports using Thorndike’s system of proportions of words per initial letter for some of his own English dictionaries. Thorndike divided the lexicon into 105 blocks, with each block containing roughly the same number of words. His proportions are given in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Proportions of English words per initial letter in Thorndike’s block system, where one block represents just under 1 per cent of the total number of words

| Number of blocks | Words beginning with: |

1 |

j, k, q, xyz |

2 |

n, u, v |

3 |

o, w |

4 |

e, g, h, i, l |

5 |

f, m, r, t |

6 |

a, b, d |

8 |

p |

10 |

c |

13 |

s |

This means, for example, that words beginning with x, y and z should between them account for just under 1 per cent of the words in the dictionary; that words beginning with c should account for roughly 9.5 per cent; and that the highest number of words (just over 12 per cent) should start with s. But it won’t be enough just to establish the projected number of words in advance: the actual words themselves need to be listed before definitions are written, since the definitions can’t include words that are not themselves defined! (See the sub-section on construction and arrangement of entries on pp. 266–70.) Where, then, do lexicographers get their words from? Do they just snuggle up in an armchair with a cup of tea and a notepad and start writing down all the words they know, perhaps starting with aardvark and moving through the alphabet?

No, of course not. For languages with a codified literacy tradition, lexicographers, like all scholars, ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ and use the wealth of scholarship already in place. For their purposes it will be lexical material compiled previously in the form of simple word lists, whole dictionaries, computerized corpora or citation indices. Word lists may be forthcoming from frequency studies like the famous Thorndike and Lorge list of the 1960s. Corpora are either commercially available to lexicographers or, for the bigger outfits, are developed as part of the dictionary-making process (see section 11.6).

Pre-existing dictionaries are, however, still the main starting point for many lexicographical projects, providing words and also citations. The venerable OED, for example, intended as an unabridged record of the entire wordstock of English from Anglo-Saxon onwards, mined extensively the word lists, glossaries and dictionaries of the Renaissance, including the first monolingual dictionary of English – Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall, from 1604 – Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755 and Randle Cotgrave’s influential A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues , from 1611. Almost a century after the initiation of the OED project, The Random House Dictionary of the English Language appeared, compiled on the basis of Barnhart’s American College Dictionary, for which his editors had trawled the OED and the semantic frequency list published by Lorge and Thorndike (1938). The OED project did use ‘armchair’ sources too, through its public Reading Programmes dating back 150 years, which collected citations from volunteers around the world.

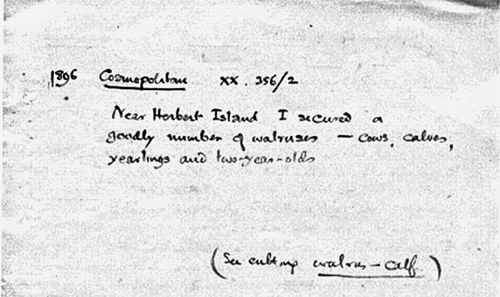

Figure 11.2 shows an index card used by J. R. R. Tolkien, author of Lord of the Rings and, during 1919–1920, a contributor to the OED, responsible for the entries spanning waggle and warlock. The (unused) quotation reads: ‘1896 Cosmopolitan xx. 356/2. Near Herbert Island I secured a goodly number of walruses – cows, calves, yearlings and two-year-olds. (See cutting walrus-calf.)’

Figure 11.2 A suggested quotation for the OED entry for walrus from J. R. R. Tolkien (Source: Oxford University Press)

The OED, like most other modern dictionaries, also uses the internet, technical databases and lexical corpora to provide evidence of its words in use. Expert consultants, normally users of specialized terminology who reveal the jargon of their craft in interviews or surveys, are also used. This kind of fieldwork is, of course, more extensively used at both selection and definition-writing stages.

We turn now to the criteria used to determine which words are selected for inclusion and which are left out. The principal factors are:

space restrictions;

space restrictions;

frequency and currency of the word;

frequency and currency of the word;

purpose/uses/users of the dictionary;

purpose/uses/users of the dictionary;

lexicographical ideology.

lexicographical ideology.

These factors overlap. Let’s use a single set of synonyms to elucidate the criteria:

chocka, farctate, full (up), FURTB, replete, stuffed

These six adjectives all mean roughly ‘full (up)’. Although an ‘unabridged’ dictionary should have entries for all of them, a pocket dictionary will probably only include one or two (at least with the sense intended here). In between, a concise or college dictionary may have entries for some of them, but not all. The pocket edition will no doubt include full (up) and maybe stuffed on the grounds that they are the most frequent words used for the concept in common usage. But the latter may not appear if the dictionary editors have what we might call a ‘conservative lexicographical ideology’ and decide not to include terms they consider to be slang or vulgar (e.g. out of a desire to ‘protect’ target users who are, say, schoolchildren or language learners). Other words may appear in concise or college dictionaries if they are old-fashioned but still used in formal, written contexts, such as replete, but the inclusion of the very rare farctate is highly improbable. The word chocka, from Australian English, is unlikely to be found outside regional dictionaries, although related chock-full and chock-a-block are likely to be included in larger dictionaries of British English. FURTB is the acronym of ‘full up ready to burst’ and is included in the online Chat Slang Dictionary of ‘slang words, acronyms and abbreviations used in websites, chat rooms, blogs, internet forums or text messaging with cell phones’. Such specialist or jargon terms are no doubt very current in the lexicons of some bloggers and web-surfers, but may not be judged pervasive or durable enough to find a place even in the largest unabridged dictionary.

Construction and Arrangement of Entries

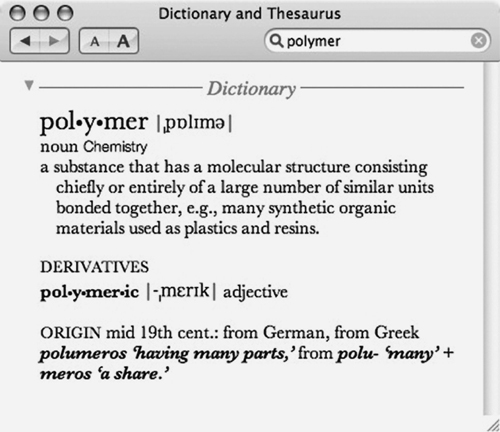

Once the words have been selected and evidence of their use recorded, the micro-tructure of each entry must be constructed, arranged together into the dictionary’s macrostructure and woven together through cross-references (the mediostructure; Hartmann, 2001, p. 65). Let’s look first at the structure of an entry in a typical general dictionary, a monolingual, medium-sized work for native-speaking adults, produced for commercial purposes. As we’ve pointed out, many dictionaries are now available in electronic format. We’ll therefore use as an example the New Oxford American Dictionary (NOAD, 2001), as bundled with recent versions of the Apple Macintosh operating system (a ‘portable version’ which comes with the print edition may also be downloaded to a mobile phone or PDA). The NOAD contains a quarter of a million entries (around the same number as the Concise Oxford (2006) or 100,000 more than Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate (2003)). Figure 11.3 shows the entry for polymer.

Cross-referencing between dictionary entries is called mediostructure. In electronic dictionaries the mediostructure takes the form of (hyper-)links.

Entries in general dictionaries mimic the entries in our mental lexicons, providing a much-abbreviated graphical sketch of the kinds of wordhood information we loosely and partially described in section 11.1. The example entry in Figure 11.3 is typical. It begins with the headword, providing spelling and syllable divisions, and is followed by a representation of the pronunciation, in this case set to ‘British IPA’ (International Phonetic Alphabet) in the application preferences. Next the grammatical properties of the word are given (namely N, indicating ‘noun’). Usage is indicated in this example simply by labelling the genre (Chemistry). The meaning of the word is given as a definition, followed by an example, but not, in this case, a citation or example of its meaning in use. Morphologically related forms are often included as ‘run-on’ entries, as here with the adjective polymeric. Finally, etymological information is given, presenting the history of the word (its earliest recorded origins, here from Ancient Greek, and its first recorded usage in English). The etymology is the only element of the entry that has no counterpart in the mental lexicon.

Figure 11.3 Entry for polymer in the New Oxford American Dictionary (Source: Apple Macintosh Dictionary application version 1.0.1)

The headword is the form of the word which appears at the beginning of its dictionary entry. It is normally uninflected and often gives syllabic information. So, for example, the headword for the entry corresponding to the word is will be be and for corresponding will be cor•res•pond.

A citation in a dictionary entry is an authentic example of the word’s use in context, to provide meaning. The citations for the first meaning of word citation in the NOAD is ‘there were dozens of citations from the works of Byron | recognition through citation is one of the principal rewards in science’.

So far, the core elements of the dictionary’s microstructure are:

headword;

headword;

grammatical properties;

grammatical properties;

usage;

usage;

meaning;

meaning;

related forms;

related forms;

etymology.

etymology.

(A seventh, citation, should be added, even though our example from NOAD doesn’t employ it.) Although there are interesting things to say about each element, let’s focus in on meaning here, along with form, which constitute the two sides of the Saussurian word coin. Meaning is far more challenging than form for the lexicographer, because although spelling and pronunciation can vary greatly across users and contexts, they are observable phenomena which can be recorded in conventional ways (most commonly using orthographic symbols, with the option of audio files for electronic dictionaries). Meanings, on the other hand, are ultimately mental representations which may be infinitely modulated by social contexts of use and are constantly shifting as we create and share new experiences of the world.

For many of us, a dictionary definition is the closest we can get when asked to think about the concept of word meaning. And lexicographers are not immune to the dilemma: Hartmann (2001, pp. 10–14) spends four pages defining the words lexicography and dictionary via reference to a series of definitions in dictionaries – including, ironically, his own Dictionary of Lexicography (Hartmann and James, 1998)! Although definitions are really no more than a string of further word forms which themselves require meanings to be associated with them (see Hall, 2005, pp. 96–97), lexicographers can’t afford the philosophical luxury of this unpalatable truth. Instead, they must buy into the folk fiction held by most of their clients, that definitions themselves ‘provide’ meaning (as we pointed out back in section 11.1). Hence, the ‘meaning’ of polymer may be represented in NOAD as ‘a substance that has a molecular structure consisting chiefly or entirely of a large number of similar units bonded together’. The phrasal meaning derived from this string of 124 characters and spaces allows the user to come to an understanding of the concept underlying the string of letters p, o, l, y, m, e, r.

One important principle of dictionary definition arising from the convenient folk fiction we have just explained is that each word in the definition must itself be defined (cf. Landau, 2001, pp. 160–162). In NOAD, one may double-click on each word in a definition and be transported to the corresponding entry along invisible mediostructure. So clicking on substance, the first noun in the definition of polymer, takes us to the entry reproduced here in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4 Entry for substance in the New Oxford American Dictionary (Source: Apple Macintosh Dictionary application version 1.0.1)

The first informative noun in the definition of substance is matter. But then matter is defined as ‘physical substance in general, as distinct from mind and spirit’. Which brings us back to substance. Landau (2001, pp. 157–163) lists a number of principles for dictionary definitions, including the one requiring each word used in the definition to have its own entry in the dictionary. But a more important one for him is the following:

Avoid circularity: ‘No word can be defined by itself, and no word can be defined from its own family of words unless the related word is separately defined independently of it’.

(Landau, 2001, p. 158)

Landau criticizes the definition of sleep in the Longman Dictionary of American English (1983) as a case where a word is used to define itself: the definition given is ‘to be asleep’ and asleep is defined as ‘sleeping’. He would surely applaud NOAD’s solution, which takes us from asleep, the adjective, to sleep, the verb, and thence to sleep, the noun, where the circle is broken with the following sleep-free definition: ‘a condition of body and mind such as that which typically recurs for several hours every night, in which the nervous system is relatively inactive, the eyes closed, the postural muscles relaxed, and consciousness practically suspended’.

The NOAD entry for polymer illustrates another way of indicating meaning: to give an example or instance alongside the definition (‘e.g., many synthetic organic materials used as plastics and resins’). A third option is to follow the synonymy route, as in the entry for concise in the Collins Paperback Thesaurus: ‘brief, compact, compendious, compressed, condensed, epigrammatic, laconic, pithy, short, succinct, summary, synoptic, terse, to the point.’ Like definitions, though, synonyms are just more words you need to know the meanings of in order to know the meaning of the words they are used to explain.

A fourth way of showing meaning was championed by Ayto (1983) and later by Carter (1998), and this focuses on the linguistic and sociopragmatic contexts in which the word is used, yielding connotative-associative aspects of meaning rather than the conceptual-denotative aspects revealed through definitions and synonyms. Some citation contexts (e.g. ‘some were inclined to knock her for her lack of substance’ in the entry for substance) are designed to augment definitions by distinguishing denotative senses. But Ayto and Carter are thinking beyond this, for example considering positive and negative associations, degree of formality, social identity of likely users, ideological presuppositions of use, stylistic implications, etc. Ayto’s example of man in phrases like Be a man well illustrates these dimensions: does the meaning of the word form man include (in such uses) a sense of courage and resolution? Two main tools would seem to be required for the unpacking of these subtleties of meaning: (1) user surveys; and (2) lexical corpora. We will be looking at corpora in section 11.6, so we end this section highlighting once more the importance of the client in applied linguistics, this time as a direct source of evidence for the ways words are used to mean. Carter (1998, pp. 270–275) provides a useful discussion of the challenges and potential rewards of such informant work. In anticipation of the discussion of technology in section 11.6, we note here that data on English word associations are now available to lexicographers online: the Edinburgh Word Association Thesaurus has association norms for over 8,000 words, collected from 100 different speakers for each word.

We’ll now turn briefly to the arrangement stage of dictionary compilation, but since most of the relevant issues have been covered in section 11.3 we’ll confine ourselves to the problem of meaning here. Notice the way polysemy is handled in the entry for substance. Typical of word forms in all languages, this one expresses a set of related meanings, each with one or more sub-meaning (or ‘sense’). In NOAD, these are listed as separate numbered or bulleted sub-entries. Lexicographers need to make decisions about where polysemy ends and homonymy begins, i.e. whether to follow form and stack up sub-entries under a single headword or go with meaning and repeat the headword in a series of numbered entries. Some cases are clearly homophones, e.g. lean the verb (as in lean on me) and lean the adjective (as in lean meat). Some are trickier: the third sense of meaning 2 of substance is no doubt a metaphorical extension of meaning 1, since emotional dependability and stability are like physical dependability and stability, a function of ‘matter with uniform properties’. But in other cases the metaphorical connection is more obtuse. NOAD treats peer (as in ‘judged by one’s peers’) and peer (as in ‘peer of the realm’) as polysemes, although few users will know of or be able to work out the metaphorical relationship (Burke’s Peerage Online tells us that ‘[t]he term peerage derives from the Latin word for equal (par) and to the extent that all peers with seats in the [UK] House [of Lords] have tended to be summoned to it irrespective of their relative rank, importance or wealth, the term still has some relevance’). Some lexicographers have argued that instead of attempting the impossible in identifying all word senses, it makes much more sense to identify different uses, using corpora (Stock, 2008 [1984]; Kilgarriff, 1997).

11.5 Dictionaries as Tools for Learning

The earliest lexicographical works were lists of words in two different languages, and had a clear educational objective: to allow users to study texts written in another language, be it Sumerian for speakers of Akkadian in Babylon 4,000 years ago or Latin for Anglo-Saxons in Kent 3,000 years later. In China around 3,200 years ago, lexicographers developed word lists to teach students learning to write Chinese characters. Monolingual dictionaries with the aim of teaching people the ‘hard’ words in texts written in their own language came much later in Europe and other parts of the world. In England, the first such text appeared as the glossary at the end of Edmund Coote’s English Schoole-Maister in 1596, with Robert Cawdrey’s Table Alphabeticall of Hard Usual English Words, appearing eight years later, as the first proper dictionary (incorporating much of Coote’s material). Both books were written principally for schoolboys, although they soon came to have more pervasive influence on adult readers. Coote’s volume consists of a series of exercises, rules and readings, followed by a list of words with definitions normally comprising single synonyms or short circumlocutions, and resembling the entries of many earlier bilingual dictionaries. Here are some examples from the letter p:

pirate sea robber.

piety godlines.

pillage spoyle in warre.

pilot maister, guider of a shippe.

planet wandring starre.

The ‘pedagogical dictionary’ tradition continues to lead much lexicographical work today. Hartmann sees the design of such works as truly applied linguistics, because they are ‘linguistic in orientation, interdisciplinary in outlook and problem-solving in spirit’ (Hartmann, 2001, p. 33). Learner dictionaries require particular care with elements of both macrostructure and microstructure, since their users are characterized by an underdeveloped lexical competence in the target language. Typically, these users are children or young adults learning their first language and additional language learners. The former group are given dictionaries to help them amass a fuller vocabulary than simple exposure to discourse would achieve. The latter group, additional language learners, having acquired at least one vocabulary, are using dictionaries to create or develop knowledge of another group’s wordstock. Then of course there are the millions who straddle both groups: children learning an additional language because their parents are immigrants, refugees or expatriates – or simply have brought them up in multilingual environments.

Children’s dictionaries are characterized by the selection of words included, the simplicity of the language they use in definitions, and normally the use of illustrations to maintain interest and support understanding. They tend to be visibly more attractive, with larger type (and more often than not pictures of large animals on the cover!). Student and college dictionaries used to look just like ‘adult’ versions, but with some simplifications and emphasis on the vocabulary of school subjects or academic writing. Now they are much more likely to come in electronic format (see section 11.6): increasingly popular among Chinese, Korean and Japanese students are e-dictionaries, handheld devices which often also incorporate voice recorder, MP3 player, video-streaming, etc. Li (2005) reported that over 70 per cent of Hong Kong Polytechnic students were using e-dictionaries more than printed versions, and this figure must be much higher now.

11.6 Corpora, Computers and the Internet

Like so many areas of applied linguistics, lexicography has been transformed by technology. Chris recalls visiting the OED offices in Oxford in 1985 to see a friend who worked there, and being shown the six inch by four inch index card with the word and citation she had been assigned to work on that day. It was less than twenty years ago that computers were first used to manage the massive database of words and citations amassed since the London Philological Society began collecting words and examples of their use in 1857. Landau (2001, p. 285) recalls that although he and his team were able to edit a medical dictionary’s entries on computer by 1984, they still had to be sent on tape to the publishing company to be processed on the mainframe computer.

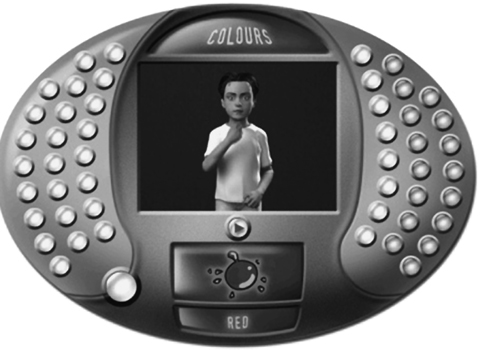

These twenty years have revolutionized the field in many ways. Editing copy is only one, rather pedestrian, area in which technology has reshaped dictionary-making. The use of corpora has brought astounding improvements (and challenges) to the lexicographical process, and the development of affordable and portable multimedia has generated a range of dictionary products that would have dazzled, or more likely terrified, Webster and Murray. Figure 11.5 illustrates one of the new incarnations of the modern dictionary. This is a dictionary of British Sign Language for young learners of the language who can read English. Imagine the benefits for deaf kids of being able to see signs actually performed in front of them by an engaging cartoon figure, rather than having to leaf through printed pages to find the static photos or line drawings using arrows that you’d find in traditional sign dictionaries (you can see the movement for yourself online). Meanwhile, the Scottish Sensory Centre at Edinburgh University is constructing a series of BSL glossaries for school subjects, using Quicktime video.

Figure 11.5 Screenshot from a British Sign Language/English online dictionary for children (Source: BSL Dictionary developed by Dunedin Multimedia for the Scottish charity Stories in the Air; reproduced with permission)

Aside from transforming access routes, format and multimedia resources in the end result, technology has had a massive impact on the core processes of collection, selection, construction and arrangement through the creation of lexical corpora and the development of associated software. We saw in section 11.1 that the mind automatically records the number of times a particular mental representation is accessed, but that is ultimately a private matter, depending on each individual’s circumstances: obstetric nurses might use the word mother hundreds of times a year more than other adults. A speaker of Aboriginal English in Australia might use the word mother more frequently than other speakers if she has many maternal aunts, since the form can be used to refer to a mother’s sisters too in that variety (Eades, 2007). Young speakers of some varieties of American English might notch up much higher frequencies of the form if they use it as a short form of the common insult and sometimes term of endearment motherfucker. Since mother is quite a formal term for female parent, some speakers may never use it at all, preferring mom, mam, mum, ma instead. And we could go on: the contents of one speaker’s lexicon will only ever resemble those of another, especially in the number of times particular form–meaning mappings have been traversed. Only a massive and representative collection of recorded usages will yield robust estimates of aggregate word frequencies across a speech community, and only computers can deliver the storage and processing capacity required to count the high numbers required and keep track of the syntactic, semantic and sociopragmatic circumstances of usage.

Hunston (2002, pp. 96–109) discusses the main impact of corpora on applied linguistic theory and practice in terms of a new focus on the following five features:

frequency;

frequency;

collocation and phraseology;

collocation and phraseology;

variation;

variation;

lexis in grammar;

lexis in grammar;

authenticity.

authenticity.

For lexicography, data on frequency of occurrence and co-occurrence in different genres of real usage has transformed the field. As we saw in the in the Chapter 9, a corpus is required if we are to assess empirically how commonly a word form is used with a particular meaning in the speech and writing of members of a speech community (instead of relying on armchair intuition). This is important for dictionary-writing at collection and selection stages (see section 11.4), in order to discard nonce words and rank priorities for inclusion by identifying highly infrequent words (like farctate), hapax legomena and emerging neologisms (see Crystal, 2000, for an estimation of the challenges this poses). At the construction stage, corpus data can be used to ensure that in entries more frequent usage is listed first, and more frequent meanings are given more attention through definition, exemplification and/or citation. (But corpus data are only as good as the corpora from which they are drawn, of course.)

Nonce words are one-off coinages, created for a specific purpose and not likely to gain common currency. David Crystal (2000, p. 219) gives the example of chopaholic, which he overheard said of someone who likes lamb chops.

Hapax legomena (from the Greek for ‘said once’; also known simply as hapax) are words with a single occurrence in a corpus. In a large corpus, around 50 per cent of words are likely to be hapax legomena. For example, the word haptic is a hapax legomenon in the British National Corpus (whereas hapax itself occurs three times).

A neologism is a newly coined word which is intended to gain or appears to be gaining common currency in the language. There are many examples at Birmingham City University’s Neologisms in Journalistic Text website.

11.7 Roles for Applied Linguists

The role of lexicographers in the broader project of applied linguistics extends far beyond the range of activities involved in the design and compilation of dictionary and thesauri we have mapped in this chapter:

In educational contexts, applied linguists can contribute to language learners’ and users’ understanding of the role and purpose of dictionaries, for both vocabulary development and guidance regarding social conventions of usage in particular domains.

In educational contexts, applied linguists can contribute to language learners’ and users’ understanding of the role and purpose of dictionaries, for both vocabulary development and guidance regarding social conventions of usage in particular domains.