www.9.1

www.9.1Chapter 9

Who this booke shall wylle lerne may well entreprise or take on honde marchandises fro one lande to anothir, and to knowe many wares which to hym shal be good to be bougt or solde for riche to become. Lerne this book diligently; grete prouffyt lieth therein truly.

(Anyone who wishes to study this book will have business success in international trade. It has all the key terms and phrases you will need for the goods you are buying and selling, goods that will make you rich. Get this book and you are guaranteed great profit.)

(William Caxton, c. 1483; an early example of a publisher’s blurb for an English–French phrasebook)

Since the origins of the discipline in the 1950s, the area of applied linguistics which has received most attention from both scholars and practitioners is without doubt that of additional language education. Early applied linguists working in language education looked to linguistics and to psychological theories of learning for solutions to the practical problem of how and what to teach. Despite (or perhaps because of) the failure to solve the problem of how to learn an additional language, a broader, more complex discipline has gradually emerged.

Additional language learners, teachers and researchers (some of us are all three) continue to think about the problem of what bits of which variety of the language to learn (or teach) and how best to learn (or teach) these bits. In English language teaching, the World Englishes movement is challenging teachers and learners to think carefully about their target variety (what to learn/teach). As the number of speakers of English as an additional language continues to grow and communication between them increases (Graddol, 2006), learners in China, for example, may prefer to be taught by a speaker of Indian English, as a more relevant (and possibly cheaper) alternative to a speaker of American or British English (D’Mello, 2004). Teachers of languages other than English are also exploring the question of target variety; for an example, recall the Somali student Mohamud learning French in Montreal in Chapter 7; or see Tew (2004) on the teaching of Moroccan French to secondary school pupils in the UK with special educational needs. As for the question of how best to learn (or teach), the search is still on, though the relevant research is more likely to be conducted on and in specific learning contexts, even specific classrooms, by teachers engaged in action research, rather than with large groups of randomly selected students specially convened for the purposes of an experiment.

Before introducing the contexts in which additional languages are learned, we’ll defend the terms we use for this chapter’s topic: additional, instead of second or foreign, and education, instead of learning or teaching. The use of second or foreign involves issues of scholarly convention, theory and sociopolitical context (as discussed in section 9.1), so we use additional because it encompasses both. And language teaching tells only half the story: learning can happen without teaching. In fact, teaching is often just a catalyst for self-directed learning, and in many cases people learn languages despite teaching. Education includes both learning and teaching and implies other things that may have an impact on additional language learning: government policy, the educational materials publishing business, folk beliefs about the personal and professional benefits of language learning; and so on. It is specifically classroom-based learning, rather than additional language acquisition in general, that we aim to explore here, though if you are interested in this related field (usually known as second language acquisition, or SLA), we have a brief introduction to some of the main themes on our companion website and two SLA-related suggestions for further reading at the end of this chapter (p. 219). On balance, we think that additional language education is the best description of our topic.

Bearing in mind that the big questions for additional language education are still what and how, we begin this chapter by taking a step back to look at the contexts of language learning (section 9.1). Then we move on to the question of how, including the problem of method (9.2) and the issue of individual learner differences (9.3). Next we look at the question of what, including assessment (9.4) and, finally, we consider some of the economic, cultural and political aspects of additional language education (9.5).

9.1 Contexts of Additional Language Education

Additional languages are learned in a wide variety of circumstances, which we may define according to overlapping clusters of factors. Perhaps the most significant of these are the following quartet: place, age, manner and purpose.

Place

Starting with place, let’s think about how the experience of learning a language is partially conditioned by cultural geography, as we observed in Chapter 2: Japanese, for example, is primarily learned as a foreign language in locations where the main language is not Japanese, for example in Pakistan or France; it is learned as a second language in locations where it is a principal language of the surrounding community, namely in Japan. This is not just a technicality. Here are some typical fundamental differences between the two contexts.

In an instructed foreign language (FL) situation, it’s likely that all learners will share a common mother tongue (L1), since they will typically come to a local classroom from a single location. In a second language (SL) environment, however, it is distinctly possible that a wide variety of L1s will be represented in the classroom, since what identifies the learner is her need for the local language: she may be an immigrant, or be combining language learning with a short holiday in a country where the target language is spoken, and her classmates may come from many different language backgrounds.

In an FL context, exposure to the target language, and hence learning and practice opportunities, will typically be restricted to classroom meeting times and homework sessions. In the SL context, however, the wider community (at least outside the immigrant learner’s immediate neighbourhood) may speak only the target language, and thus the learner will have many more opportunities, as well as possible pressures, to learn the new language. Indeed, SL learning may be a matter of national identity, economic opportunity, of conflict or of pride, whereas FL learning can typically be more an individual process, undertaken as an optional part of schooling, for example, or for personal growth, or to prepare for work or travel to places where the target language is spoken.

In FL contexts, it is more likely that a learner’s L1 will be used as a vehicle for learning and teaching, since teachers and other learners are likely to be speakers of the same language. Most internationally distributed teaching and testing materials for English, however, assume an SL context, are written solely in the target language and are published by a small number of big UK and US publishing companies. Where such materials are used by teachers in FL contexts, some of the cultural markers of groups living in those particular places become embedded in the language learning experience.

One domain in which cultural geography is perhaps less central to the task of additional language learning is the World Wide Web. Resources for online language learners designed to give students practice in listening, reading, grammar and vocabulary have proliferated in the last decade, and speaking and writing practice has been made much easier by blogging (and other web-based writing formats) and internet telephony. Until very recently, such resources have been only superficially place-based (for example a webpage which uses the Union Jack to mark a programme aimed at students and teachers wishing to learn and teach British English), but even the disembodied domain of the internet is now being mapped through the creation of virtual ‘villages’, ‘islands’ and other spaces for language learning (for example in Second Life, a virtual world in which more than 30,000 users were logged on at any one time in 2008).

Age

Turning now to age, we might recall the reference to a biologically determined ‘critical age’ for language learning in Chapters 1 and 3. There we pointed out that although children may be better equipped in biological terms for learning an additional language, they may lack the attention span, motivation, social strategies and confidence that some adults are able to deploy. We’ll have more to say about the individual outcomes of additional language learning in section 9.3, but for the moment let’s settle the related terminological issue raised at the beginning of the chapter: the difference between acquisition and learning. The former term has been used most in the context of the unconscious, dedicated cognitive processes by which linguistic knowledge and abilities unfold in infancy on the basis of input from the environment. Language development in this sense is innately driven, resembling the ability to walk on two feet or the ability to recognize individual faces, which emerge very early in life. Language learning, on the other hand, has been used to refer to the consciously deployed general problem-solving processes used in the kind of language study typically undertaken by adults (Krashen, 1981; Bley-Vroman, 1989).

Acquisition is the mental process by which knowledge and/or behaviour emerges naturally on the basis of innate predisposition and/or triggers from environmental input (e.g. walking on two feet). Learning, on the other hand, requires conscious effort and leads to skills which cannot be part of our genetic make-up (e.g. walking on stilts).

Given that (1) the learning/acquisition distinction is still a hypothesis, rather than an indisputable fact; and (2) learning is the more general of the two terms in non-technical usage; and (3) applied linguists can in any case influence deliberate learning processes more than they can unconscious, automatic acquisition, we prefer to use the adjective learning to label here the process of coming to know and use an L2, irrespective of age.

Manner

The third factor, manner, refers to how additional languages have been learned and taught in different places and different times. While scholarly research on additional language education (in the field commonly known as second language acquisition) may have influenced practice in many contexts from the second half of the twentieth century onwards, other significant factors have always included more practical issues, such as:

teachers’ and learners’ beliefs about teaching and learning (including, for example, the benefits of drilling, the best way to teach grammar or whether and how to correct students’ mistakes);

teachers’ and learners’ beliefs about teaching and learning (including, for example, the benefits of drilling, the best way to teach grammar or whether and how to correct students’ mistakes);

the availability of well-trained teachers;

the availability of well-trained teachers;

the availability of resources (for example: class size and classroom furniture; number and origin of textbooks and study materials for students; access to learning technologies such as a photocopier, an audio/video player, a computer, the internet);

the availability of resources (for example: class size and classroom furniture; number and origin of textbooks and study materials for students; access to learning technologies such as a photocopier, an audio/video player, a computer, the internet);

achievement and proficiency tests, where practice test exercises are used in lessons or as part of independent study.

achievement and proficiency tests, where practice test exercises are used in lessons or as part of independent study.

We return to manner, and the problem of method, in section 9.2.

Purpose

And finally purpose. An example of what we mean here can be found in the metaphor of ‘command and demand’ motivations for English language education (Maguire, 1996). Command-motivated programmes are those in which the state or national curriculum obliges students in government schools to study in a particular language or languages. In contrast, programmes motivated by demand are privately organized and funded, market-driven schools that arise and thrive where individuals want language-in-education services that are not provided by government schools and colleges. Here’s an example from one Indonesian city, Bandung (population around two million). Command-motivated programmes require English, Sundanese (the regional language of West Java) and an additional language, usually Mandarin, as compulsory primary and secondary school subjects. Demand-motivated programmes are offered by private primary and secondary schools teaching core subjects, such as science and mathematics, in English. There are also numerous privately owned English language schools, for children and teenagers who learn the language in the hope that their school marks or future prospects may be bettered, business people who attend classes as part of a compulsory in-service training programme or voluntarily after work, and students hoping to study at a university in another country. Finally, as in most countries, there are many freelance language teachers offering a wide range of languages for one-to-one tuition.

Place, age, manner and purpose are four of the many overlapping and interacting variables in any additional language learning context. Of these variables, manner, the subject of section 9.2, is perhaps of greatest interest to researchers and practitioners alike.

9.2 The Problem of Method

Changes in methods for teaching languages are underpinned by the assumption that the fragments of language we teach, and the way in which we teach them, facilitate (or, put more strongly, cause) learning. Not only do methods facilitate learning, the assumption goes, but some methods are better at facilitating learning than others. Indeed, if we could only find it, there would be a ‘best’ method, a method that would ‘fix’ the language learning problems of all those students who currently struggle to get anywhere with a second language. In an attempt to discover this ‘best method’, a number of research projects (often referred to now as the ‘methods comparison studies’) were conducted in the 1960s against a backdrop of enthusiasm for the latest development in educational technology, the language laboratory. The methods comparison studies aimed to find out whether audiolingual methods, with an emphasis on listening and speaking, were more effective than traditional grammar translation methods. The findings of one study of almost 1,800 US schoolchildren learning French and German are typical: children taught an additional language over a period of two years using ‘new’ audiolingual methods were no better at listening, speaking or writing, and worse at reading, than their peers who had been taught using traditional methods. The study concludes that differences in classroom methodology are not associated with difference in attainment and that language labs are unlikely to be cost effective, given that they were not shown to accelerate learning and that there were cheaper ways of recording students (Smith and Baranyi, 1968).

The audiolingual method of teaching an additional language is characterized by repeated oral grammar drills and the outlawing of the L1. Maximilian Berlitz was a pioneer, using the method to teach French and German in the USA. But over 130 years later the company he started now favours a less rigid learning regime.

The grammar translation method of teaching an additional language focuses on memorization of L2 grammatical rules and translation of texts from the L2 into the L1. The method’s origins lie in the European tradition of teaching schoolchildren the great works of ancient Greek and Latin.

Despite the failure of the methods comparison studies to provide evidence for an association between method and attainment, the lure of the ‘best’ method continued to exert its influence over subsequent decades of educators. For a vivid example, look on YouTube for the short extract from the television documentary A Child’s Guide to Language (BBC, 1983). In the extract, James Asher, an early proponent of the Total Physical Response (TPR) method, suggests that it will, in future, make it feasible for pupils to leave primary school with three or four additional languages, which could then be ‘fine-tuned’ for grammar, reading and writing at secondary school. More than twenty-five years after this documentary was made, the promise of TPR, and of a ‘best’ method in general, has not been realized. Indeed, the very idea that there is a single, best method that will facilitate learning in widely varying teaching situations is falling out of fashion (although not always out of practice) and has gradually been replaced with a concern for the unique characteristics of individual learners and classrooms, discussed in more detail in the sections that follow.

Total Physical Response (TPR) is the compelling name given by James Asher to the additional language teaching method he developed. It attempts to recreate for learners the conditions of first language acquisition by getting them to listen and respond with appropriate physical action to spoken instructions. They do this for an extensive period before attempting to speak themselves.

What is a Method?

The word method has been variously defined (for example Pennycook, 1989; Prabhu, 1990). Figure 9.1 shows one way of conceptualizing the components of a method and their relationship with each other. In this model, method is an umbrella term that includes an approach (based on theories of language and language learning), a design (the organization of the teaching laid down in syllabi and lesson plans) and a procedure (what happens in the classroom). Describing a lesson using this model can help teachers to externalize their beliefs about language and learning, as well as to examine the consistency of what course documents say about a method (its approach and design) and the realization of the method in the classroom (the procedure). So, as a descriptive tool, the model is quite useful. However, there is a danger here of appearing to claim that all a teacher (or a syllabus or coursebook writer) needs to do is to assemble her chosen method, based on the framework above, apply it to any teaching situation and, hey presto, her students will learn in the optimal manner. In reality, pre-existing variables will all interact with the method to shape how teaching and learning actually take place: the students’ expectations of classroom language learning, the size of the room, the climate, the perceived status of the teacher, the importance attached to assessment, the degree of surveillance of teachers’ practice by managers or inspectors, etc., will all conspire to create specific local contexts in which methods must be shaped. It is this relationship between learning contexts and teaching methods that provides the backdrop for the rest of this section.

Figure 9.1 What is a method? (adapted from Richards and Rodgers, 2001, p. 33)

Appropriate Methods in Different Contexts

Bearing in mind that contexts of additional language learning vary according to the place and manner in which learning takes place, should language teachers be looking for the most appropriate fit between a (variety of) method(s) and their teaching context? What would looking for a ‘best fit’ involve anyway? At least the following:

acknowledging that no single method or combination of methods has been comprehensively validated by research;

acknowledging that no single method or combination of methods has been comprehensively validated by research;

attempting to understand students’ (and possibly parents’ and school managers’) expectations of their teacher, the methods and the learning outcomes;

attempting to understand students’ (and possibly parents’ and school managers’) expectations of their teacher, the methods and the learning outcomes;

considering the feasibility of the method (does it require any special equipment, a large teaching space, noisy group work in an otherwise quiet learning environment?);

considering the feasibility of the method (does it require any special equipment, a large teaching space, noisy group work in an otherwise quiet learning environment?);

becoming aware of the assumptions about language and learning that underpin the method;

becoming aware of the assumptions about language and learning that underpin the method;

thinking through any messages conveyed by the method about language communities, the students’ (lack of) participation in these communities and the possible social and economic consequences of this.

thinking through any messages conveyed by the method about language communities, the students’ (lack of) participation in these communities and the possible social and economic consequences of this.

Writers in the critical pedagogy tradition have strongly suggested that it is the responsibility of all language teachers, including those working in the context where they themselves learned, to think very carefully about their own cultural, social and political contexts and how these influence their beliefs and classroom practices – and also to encourage their students to do the same (Canagarajah, 1999; Pennycook, 1994b; Phillipson, 1992, 2009).

Three final cautions. First, generalizations about regions, countries, speakers of a language and even specific groups of students are inevitably inaccurate. Differences within groups of students mean that providing the ‘best fit’ between context and method involves using a variety of methods, in the belief (or hope) that some will be appropriate for some students some of the time. Second, such eclecticism must be principled, and the effects of the method on students carefully evaluated. Finally, it is important to remind ourselves that what some authors have pointed to as the ‘unravelling’ or ‘decomposition’ of certainties about additional language teaching (Larsen-Freeman and Freeman, 2008) might not be welcomed by everyone, for example by novice teachers or traditionally minded supervisors and students. A colleague of ours once wasted his students’ time by asking them to write a sentence on a piece of paper suggesting how he could improve his teaching. To his dismay, all the pieces of paper he collected were blank, except one that said, ‘Please wear a belt.’ Where the value of talking to students about methods is unclear to them, our students might find it would be inappropriate (or pointless) to comment.

9.3 Individual Learner Differences

Research in second language acquisition has highlighted some of the cognitive resources that all learners bring to the task of additional language learning, especially those developed during first language acquisition. One powerful resource is the mind’s capacity to automatically assimilate new information into the networks of knowledge already stored in long-term memory. It is this ability that underlies universal processes of cross-linguistic influence, whereby first language features appear in the learner’s developing second language (e.g. a ‘foreign’ accent). It is also reflected in the fact that translation between L2 and L1 is the inevitable process occurring in learners’ minds in the beginner or intermediate classroom, whatever the teacher or the curriculum says about ‘banning’ L1 use (see Cook, 2010). But although there are commonalities across learners, they are normally beyond the reach of the classroom teacher and, in any case, are often positive in their effects. It is the differences between individual learners that present the greatest challenges for teachers.

Cross-linguistic influence is when the knowledge or use of one language affects the learning or use of another (typically, L1 influencing L2). The traditional term for this phenomenon is transfer. Another term, interference, wrongly implies that all L1 influence on L2 learning has negative effects.

Interest in the individual differences between language learners has been a feature of SLA studies since the 1960s. Early research on this topic took place in the field of language psychology, where, for example, attempts were made to understand the contribution of an ‘aptitude’ for learning additional languages – an attractive proposition for admissions boards and policy-makers hoping to avoid wasting money on those less likely to learn. In the 1970s, research into the ‘good language learner’ suggested that, in addition to ‘who they are’ (including what were considered ‘fixed’ qualities such as age, aptitude and motivation), ‘what they do’ also matters. Successful learners were those who used a range of learning techniques (strategies – like keeping vocabulary records and using memorization techniques) to help themselves learn. In this section, we return to the issue of age, and assess the contribution of aptitude, motivation and language learning strategies.

Individual differences between learners are those which potentially account for the wide variety of paths followed and ultimate outcomes achieved in additional language learning. A European Union project called Don’t Give Up provides examples of best practice for giving adult language learners motivation, one of the biggest differences between successful and unsuccessful learners

Age

All of the individual learning differences discussed in this section interact with each other to some extent. Age, however, is probably the one which most affects all the others. The theory that there is a relationship between ultimate success in language attainment and age is known as the critical period hypothesis (CPH). Lenneberg (1967) suggested that, for reasons to do with the way the brain develops, the optimum age for language acquisition is between two years old and puberty. Most researchers now agree that there is a critical period for first language acquisition, though there is more controversy about the relationship between age and additional language acquisition, because of the difficulty of controlling for other possible factors. Research by Long (1988), however, suggests that the critical period for acquiring ‘native-speaker’-like pronunciation is before the age of about six, and that ‘native-speaker’-like grammar can be acquired up to the age of puberty. Consistent with Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar, it seems that children have a mental toolkit for extracting regularities from linguistic input, which adults have lost.

According to the critical period hypothesis, there is a limited window of opportunity for language acquisition, during which input must be received and processed, before the innate cognitive mechanisms responsible for the process ‘shut down’.

Of course, the fact that many children are ultimately more successful at learning an additional language than most adults does not mean that adults are never successful learners, that all children are successful or that the best time to learn a new language is in primary school. Despite these important caveats, the idea of teaching an additional language to children has proved an irresistible one to policy-makers keen to promote multilingualism as a marketable advantage of their country or region, as we saw in Chapter 8. This policy preference is one manifestation of popular ideas about children being language ‘sponges’, as we discussed in Chapter 1.

Overall, research has shown that age is a critical factor in ultimate attainment in an additional language but that younger is not always better and that there are important intervening variables such as: access to quality instruction; informal opportunities for language input and production; motivation, time management and willingness to study; other languages spoken, their influence on the additional language; and aptitude. These intervening variables make research findings about age difficult to generalize between different learning contexts.

Aptitude

Like age, aptitude has proved an attractive individual difference to policy-makers tasked with making decisions about additional language education. Generally, language aptitude tests have been used to identify and exclude those students who are likely to make slower progress in learning an additional language than others. Dörnyei (2005) describes how aptitude tests were used in the 1920s and 1930s in the USA with the intention of improving the overall success of language teaching in schools by excluding from language classes those students who were predicted to learn at a slower rate. In the 1950s and 1960s, when two widely used tests, the Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT) and the Pimsleur Language Aptitude Battery (DeKeyser and Juffs, 2005), were developed, the rationale for testing was the same: how to maximize the cost-effectiveness of additional language education.

What exactly language aptitude is has long been a matter of debate. One of the originators of the MLAT, John Carroll (1981), has described language aptitude as a combination of:

phonetic coding ability (being able to distinguish between different sounds and remember them);

phonetic coding ability (being able to distinguish between different sounds and remember them);

grammatical sensitivity (being able to work out what each word is for in a sentence);

grammatical sensitivity (being able to work out what each word is for in a sentence);

rote learning ability (memorization);

rote learning ability (memorization);

inductive language learning ability (being able to identify patterns or relationships of meaning or form).

inductive language learning ability (being able to identify patterns or relationships of meaning or form).

Scholars currently working in the field of language aptitude are debating whether working memory (where information is initially processed and temporarily stored) may be one, or even the most important, component of language aptitude (Robinson, 2002).

Most schools around the world are unlikely to be able to afford the language aptitude tests that are commercially available. Anyway, for teachers, proficiency is probably of more interest than aptitude: they may be able to move between classes students who are not at the ‘right level’, but they are unlikely to be able to exclude students altogether for being hopeless learners. Many language teachers are, however, interested in the related area of cognitive learning styles, and although scholars continue to disagree about what learning styles are and even whether they exist, many teachers try to plan lessons with a variety of activity types to appeal to different learners (for example, so-called visual learners versus experiential learners). Finally, for some language education planners and managers, aptitude continues to be an appealing concept. The US Department of Defense, for example, uses aptitude testing to decide which of its new recruits will be trained as military linguists. Other users include: intelligence agencies and religious organizations, to identify the candidates most likely to be successful learners of the new language(s) needed for international posting as spies and missionaries; educational psychologists who are working with students who have failed in efforts to learn an additional language; and school managers who wish to select students for an accelerated language learning programme.

Learning styles are the different approaches people are believed to take to the acquisition of new information. The popular distinctions between ‘visual’ and ‘tactile’ learners, or between ‘thinkers’ and ‘doers’, illustrate the concept. Some scholars believe that if learners can identify their preferred style(s) they will be able to optimize their learning. Decide for yourself using North Carolina State University’s online Index of Learning Styles questionnaire.

Motivation

Ask any language teacher what makes a successful language learner and you will probably hear ‘good motivation’. Ask the students on the other hand, and you might hear that the key to success is a teacher who motivates them! Where motivation comes from, what it is and what kinds of motivation are the most helpful in language learning have been a matter for discussion in social and educational psychology and applied linguistics for at least half a century.

In research that continues to influence the ideas of language teachers today, Robert Gardner, a social psychologist, together with his students and associates, developed a framework for linking the reasons people learn additional languages with their success in learning. Conducted in Canada, this research used attitude questionnaires to measure the strength of what was conceived of as an individual, mind-based phenomenon. Gardner (1985) suggested that for some learners the desire to become part of a target-language-speaking community (integrative orientation; see Figure 9.2) was more strongly associated with success, while for others the usefulness of the target language within the learner’s own community was more effective (instrumental orientation). Other research in educational psychology, mainly conducted outside Canada in the 1990s, developed the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-confidence and effectiveness, as well as the situation-specific motivations associated, for example, with feelings about the teacher, the course and fellow students. Research methods included the measurement of learners’ actual classroom behaviour (rather than asking them to complete surveys, as Gardner and his colleagues had done), including: observing attention spans, choice of tasks and changing levels of participation in groups and whole-class work.

Figure 9.2 Integrative motivation reinforced for an Italian immigrant to the USA in 1918

(Source: National Geographic)

Integrative and instrumental orientations to additional language learning result in different types of motivation to learn. Learners may desire to learn the language to integrate themselves into the community of L2 speakers or to use it as an instrument for some other benefit. An example of the former would be someone who learns Arabic after converting to Islam. An example of the latter would be someone who learns Arabic in order to win a contract to build a mosque.

Additional language learners have intrinsic motivation when the process itself is perceived as rewarding (for example the intellectual satisfaction they may gain from fathoming a complex verb conjugation). They have extrinsic motivation when success provides external rewards or is coerced (for example when they need to learn the conjugation in order to pass a test).

More recently, research using learners’ verbal reports of their behaviour and attitudes has led to greater emphasis on the interaction between reasons for wanting to learn, the strength of the desire to learn, the kind of person a learner is and the specific situation she finds herself in. Dörnyei’s (2001, 2005) concept of a second language ‘motivational self system’ proposes three main sources of the motivation to learn a language: the learner’s vision of him/herself as an effective user of the additional language; social pressures on the learner to succeed or to discourage success; and positive learning experiences.

Many of the ways in which many teachers already try to motivate their students are consistent with Dörnyei’s concept. Depending on the learning context, they may include:

creating a positive rapport with students by being friendly and interested in their learning, taking care to plan relevant, challenging lessons;

creating a positive rapport with students by being friendly and interested in their learning, taking care to plan relevant, challenging lessons;

observing which activities students seem to enjoy or work harder on than others;

observing which activities students seem to enjoy or work harder on than others;

using examples in the class of interesting or famous target-language speakers and places where the target language is spoken;

using examples in the class of interesting or famous target-language speakers and places where the target language is spoken;

encouraging students to work towards tests as a way of recording progress;

encouraging students to work towards tests as a way of recording progress;

recommending self-study activities;

recommending self-study activities;

playing songs and showing films in the target language;

playing songs and showing films in the target language;

stressing the benefits of an additional language and the disadvantages of speaking only one language;

stressing the benefits of an additional language and the disadvantages of speaking only one language;

creating a feeling of obligation to attend and participate in the class.

creating a feeling of obligation to attend and participate in the class.

Learning Strategies

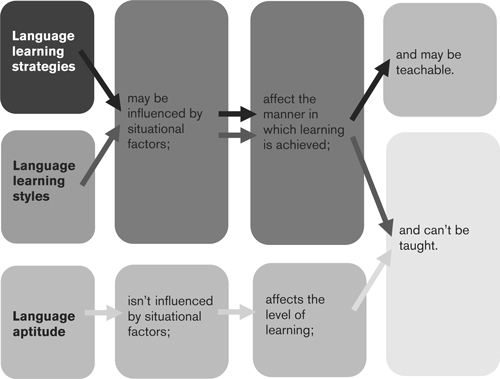

Individual learners seem to differ in how they go about learning additional languages; for example, some people like to make and memorize lists of words, others prefer to find or create situations in which they can speak the language, and others like to do both. When a learner chooses to do something that facilitates learning, this action is known as a learning strategy. What causes different learners to use different learning strategies, as well as how to classify and measure these strategies and whether they can and should be taught to learners, is, however, controversial. So why do learners seem to differ in their choice of learning strategies? Consciously chosen learning strategies are often presented as the surface manifestation of more stable, unconscious learning styles, part of individual cognition. Figure 9.3 illustrates some of these points, relating styles and strategies to aptitude.

Figure 9.3 The relationship between language aptitude, language learning styles and language learning strategies

How far learning strategies are related to cognitive factors and to what extent they are the approved learning behaviours that arise in interaction with a particular learning context or culture is not clear. In part because of this confusion over what strategies are, their measurement has also proved difficult. Measurement instruments have tended to rely on questionnaires which students themselves answer, introducing problems of self-awareness and social desirability bias. Whether teaching students to use new learning strategies is worthwhile is another cause of controversy, with reasons in favour including: increased self-awareness and ability to self-direct learning; arming students with a greater range of tactics for dealing with the demands of new learning situations; and providing the basis for a fun classroom discussion on themselves (everyone’s favourite topic). On the other hand, reasons for not teaching students to use new learning strategies include: the impracticality of providing class time for learning strategies to suit all students, especially in large classes; the possibility that learners may already be using the learning strategies that suit them best and may not want to or be able to change; and the problem of not really knowing how learning strategies interact with other individual learner differences, including the possibility that the manner in which you learn may not affect your level of achievement.

Another group of strategies that it may be useful to draw students’ attention to are compensatory strategies (Tarone, 2005). Compensatory (or simply communication) strategies are ways of talking that are aimed at avoiding misunderstanding (for example not mentioning or abandoning a problematic topic) and/or achieving understanding (for example monitoring for signs that the listener has understood, using a description or example of a thing where the specific word or phrase is not known). For information about the relevance of compensatory strategies for people with language-related disabilities, see Chapter 13.

Speakers use compensatory strategies when linguistic interaction is compromised in some way, because one or more of the interlocutors lacks relevant linguistic knowledge or ability. For example, circumlocution can compensate for word-finding difficulties.

9.4 Assessing Additional Languages

Can language really be tested? To non-linguists, this might seem like a silly question. After all, job seekers routinely use test results to quantify their linguistic knowledge in some form or other (e.g. ‘near-native speaker of Korean’, ‘reading knowledge of Portuguese’, etc.). And governments around the world seek to assess whether immigrants and asylum seekers have sufficient knowledge of the host language(s) to be permitted entry and/or settlement (Shohamy and McNamara, 2009). People are taking countless different language tests around the world which, like the compulsory College English Test for all university students in China who wish to graduate, can make a huge difference to the life chances of the test-takers.

But what about applied linguists? Given increasing sophistication in appreciating the complexities of additional language use, can we truly measure with confidence and precision ‘how much’ or what aspects of a given language a person has attained? And, following our deconstruction of ‘language’ in Chapter 2 and discussion of standards and varieties throughout this book, which ‘Chinese’ or ‘English’ would we expect learners to show they know? For applied linguists, then, the question ‘Can language really be tested?’ presents a serious challenge. Some linguists claim that the additional language knowledge cannot be measured by tests at all (Troike, 1983), but rather only through regularly observing, over time, the real-life tasks that learners perform in the language they are learning (order a takeaway meal by telephone, write a job application letter, read an applied linguistics textbook), avoiding the kind of decontextualized assessment that we come back to in Chapter 13. An informed and honest answer to the question of whether language proficiency can be reliably and validly measured is probably ‘not really’ or ‘not very easily’. Despite this, as we’ll explore in this section, a large and powerful language testing industry has developed to meet the (perceived) needs of individuals and institutions to establish what learners ‘know’ about additional languages. In this section, we take the position that assessment is a necessary fiction that both we, as additional language teachers, and our students maintain through our daily practice.

The aim of additional language assessment is to judge attainment using, for example, a test, a learning journal, project work, a portfolio, observation or peer- and self-assessment. What makes additional language assessment interesting to applied linguists is the interaction between its psychological and social aspects, including ongoing debate on questions such as:

A construct in testing is the ability, skill or knowledge that the test is (supposedly) testing.

What should (and shouldn’t) language assessment measure (the construct)?

What should (and shouldn’t) language assessment measure (the construct)?

How should learners be made to demonstrate the construct being measured?

How should learners be made to demonstrate the construct being measured?

How should this demonstration be quantified and measured in a way that doesn’t distort the construct and is understandable to the public?

How should this demonstration be quantified and measured in a way that doesn’t distort the construct and is understandable to the public?

How can tools be developed so that learners can assess their own attainment?

How can tools be developed so that learners can assess their own attainment?

How should (especially large-scale) assessment be organized fairly and efficiently?

How should (especially large-scale) assessment be organized fairly and efficiently?

What are the consequences of testing for learners in their ongoing learning and general life chances?

What are the consequences of testing for learners in their ongoing learning and general life chances?

Although there is no current consensus on the best answers, anyone who is interested in creating an additional language assessment, or in using assessment scores to make decisions about users of additional languages must be prepared to consider these questions. In this section, we’ll review some possible answers to the first and the last of our questions, as the ones which have generated the most recent debate. We’ll finish with some thoughts on ways in which the questions might interact with each other in complex and intractable ways.

Reasons for Testing and Models of Language

So, what should (and shouldn’t) language assessment measure? Your answer will partly depend on your reason for testing in the first place. Possible reasons for testing include:

Placement: to match a learner’s current level of knowledge with an appropriately challenging course.

Placement: to match a learner’s current level of knowledge with an appropriately challenging course.

Diagnostics: to find out what a learner knows and doesn’t know, perhaps to provide input into the design of a course or plan individualized instruction.

Diagnostics: to find out what a learner knows and doesn’t know, perhaps to provide input into the design of a course or plan individualized instruction.

Achievement: to find out which of the planned learning outcomes of a course have been met by a learner. Achievement tests can usually be ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ and are sometimes used to decide whether a student is allowed to continue to the next level of proficiency, while on other occasions they can be used to motivate learners by providing proof of progress.

Achievement: to find out which of the planned learning outcomes of a course have been met by a learner. Achievement tests can usually be ‘passed’ or ‘failed’ and are sometimes used to decide whether a student is allowed to continue to the next level of proficiency, while on other occasions they can be used to motivate learners by providing proof of progress.

Proficiency: to get a general idea of a learners’ current knowledge of the language. Proficiency tests may be ‘pass or fail’ where they are part of a suite of tests, like the five Cambridge ESOL General English exams. Other proficiency tests, like the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) or the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), are not pass or fail tests but are scored at different levels (e.g. from non-user to expert, low to high or weak to strong). Although such tests are not marked on a pass or fail scale, a candidate who fails to achieve the score required for university entry or immigration purposes will most likely feel she has failed the test.

Proficiency: to get a general idea of a learners’ current knowledge of the language. Proficiency tests may be ‘pass or fail’ where they are part of a suite of tests, like the five Cambridge ESOL General English exams. Other proficiency tests, like the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) or the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), are not pass or fail tests but are scored at different levels (e.g. from non-user to expert, low to high or weak to strong). Although such tests are not marked on a pass or fail scale, a candidate who fails to achieve the score required for university entry or immigration purposes will most likely feel she has failed the test.

Of course, two or more of the reasons for testing mentioned above can be combined in a single test. For example, a test might be used to place students in a suitable class and show the teacher what the student does and doesn’t know. Or, to show which learning outcomes have been achieved and diagnose which ones haven’t (and so need to be addressed through instruction or covered in subsequent courses). While your answer to the question ‘What should (and shouldn’t) language assessment measure?’ will partly depend on your reason for testing, as we suggested above, it will also depend upon your model of language, that is, the language feature(s) or abilities that you are actually aiming to assess. One way to look at proficiency levels, then, is to see them as based on definitions of ability, performance, interaction and hierarchical frameworks.

Ethics and the Consequences of Testing

The last on our list of ‘must-ask’ questions was ‘What are the consequences of testing for learners in their ongoing learning and general life chances?’ This question raises the important issue of ethics in testing. Up until about twenty years ago, a fair assessment was generally considered to be one that was valid (measures what it says it measures, its construct validity) and reliable (produces consistent results between test-takers and across multiple administrations of the same test). More recently, however, the concept of validity has been broadened beyond that of a test-internal measure to include consideration of the social, educational and political contexts of tests, and the problems that assessment might cause. Issues include:

Construct validity refers to how well some measurement system correlates with the construct it is designed to measure. You might, for example, have an opinion on the construct validity of the online Index of Learning Styles questionnaire, which uses multiple questions with two-option answers to assess your learning styles on four scales.

In testing, washback refers to the positive and negative effects of testing on learning and teaching. So, for example, tests might boost self-confidence if they give learners the opportunity to show what they know (positive), or restrict what they learn if the constructs tested are known in advance and are allotted unbalanced study time (negative).

the positive or negative effect (washback) of the assessment on the test-takers’ learning;

the positive or negative effect (washback) of the assessment on the test-takers’ learning;

the kind of test-taker for whom the assessment is (un)suitable;

the kind of test-taker for whom the assessment is (un)suitable;

the myth that there is one form of the language being assessed and that there are ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ versions of this language;

the myth that there is one form of the language being assessed and that there are ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ versions of this language;

how the method of assessment (including the interlocutor in a speaking test) might affect test-takers’ scores;

how the method of assessment (including the interlocutor in a speaking test) might affect test-takers’ scores;

the uses to which the results of the assessment will be put, including whether they will limit the test-takers’ access to opportunities for self-improvement and whether the test-takers are aware of this;

the uses to which the results of the assessment will be put, including whether they will limit the test-takers’ access to opportunities for self-improvement and whether the test-takers are aware of this;

the creation of a lucrative market for tests, test preparation materials and test preparation courses;

the creation of a lucrative market for tests, test preparation materials and test preparation courses;

whether it’s possible to avoid the results of additional language assessments being confounded by intervening variables such as socioeconomic status, perseverance, conformity, test practice, peer or parental influence, background knowledge of the topic, etc. (Shohamy, 2001; McNamara and Roever, 2006).

whether it’s possible to avoid the results of additional language assessments being confounded by intervening variables such as socioeconomic status, perseverance, conformity, test practice, peer or parental influence, background knowledge of the topic, etc. (Shohamy, 2001; McNamara and Roever, 2006).

It’s not altogether clear how additional language assessment will deal with the serious ethical issues that a broader concept of validity has drawn our attention to. Where assessment decisions are made by language teachers, in conjunction with their students, innovative forms of assessment that are supportive of learning are likely to emerge. Less supportive might be the decisions made by the commercial organizations that organize and profit from large-scale testing (useful though their services are to the gate-keepers of opportunities for study and work).

9.5 Economic, Cultural and Political Aspects of Additional Language Education

The Critical Language Teacher

Critical approaches to language teaching are those which demand careful thought about the connections between why (and how) a language is being learned (and assessed) and the social, economic and political contexts of additional language use (and assessment). Importantly, the critical language teacher doesn’t just think about these connections; she encourages her students to think about, and act to change, attitudes and practices that disadvantage them as additional language learners and users (see also the sub-section on critical discourse analysis in Chapter 4, on pp. 88–9). Having a critical approach to teaching, learning and assessment has become known as critical pedagogy (CP). Advocates are very clear that as a method of teaching CP is necessarily sensitive to specific language learning (and using) contexts. This means that, while we can describe what CP is at the level of approach (see Figure 9.1), the design and procedure of this method will vary from classroom to classroom (Norton and Toohey, 2004).

Critical pedagogy is an approach to teaching which encourages students to develop critical awareness of, and to challenge, explicit or implicit systems of social injustice and oppression. It is particularly associated with the work of Paulo Freire.

Are Language Teachers (Un)Critical?

Language teachers don’t always worry about the connections between their classroom work and the wider social implications of learning, teaching and assessment in additional languages. One rationale for not worrying is that students are ‘empty vessels’ into which a new language can be simply poured, with no other consequence than the eventual achievement of ‘proficiency’. Another rationale is that (for some students anyway) learning an additional language is a personal choice which provides them with access to jobs and study opportunities that might otherwise not have been available. A further rationale is that teaching the world’s most frequently spoken languages constitutes a possible channel for increased mutual understanding between groups, maybe even improving the likelihood of peaceful relations within or between countries. These three reasons for not needing to worry about the social implications of why and how additional languages are taught and assessed can be summed up thus: ‘the beneficiaries of my teaching are the students who are gaining good communication skills; making them more employable and more accepting of other people and other cultures.’

But the teaching of English, and, by implication, any of the world’s most frequently taught languages, has been shown to result in financial, diplomatic and trade benefits to English-speaking countries, and the business of English language teaching conceals a complicated picture of influence by already powerful and influential groups over less powerful groups encouraged to feel in need of (an) additional language(s) (Phillipson, 1992, 2009).

Still, language teachers often work under considerable pressure: teaching for long hours and being held responsible both for maintaining students’ motivation and for ensuring good results on the end-of-course test. Where schools or students can afford them, published materials with glossy pictures and extensive teacher’s notes, and tests which claim to be ‘standardized’ and ‘international’, might seem like an attractive solution to some of these problems. The critical language teacher, however, will use these materials and tests with caution, asking themselves and their students questions about who is benefiting from (and who is disadvantaged by) any particular version of the language and the language learning experience. Specifically, the critical language teacher will insist on asking difficult questions, such as:

What do my students bring to their lessons (beliefs about learning, language learning goals, expectations of interaction in the additional language, judgements about my personality and professional competence and so on)?

What do my students bring to their lessons (beliefs about learning, language learning goals, expectations of interaction in the additional language, judgements about my personality and professional competence and so on)?

What is the social and economic status of my students in target-language situations and how might this affect their opportunities to interact in the target language, as well as the ways in which these interactions will be judged?

What is the social and economic status of my students in target-language situations and how might this affect their opportunities to interact in the target language, as well as the ways in which these interactions will be judged?

Who is allowed to decide what I teach, how I teach it and how learning is assessed? What are the consequences of these decisions for my students? In addition to my students, who benefits or is disadvantaged by these decisions?

Who is allowed to decide what I teach, how I teach it and how learning is assessed? What are the consequences of these decisions for my students? In addition to my students, who benefits or is disadvantaged by these decisions?

Native-Speakerism

Becoming (or at least sounding and writing) indistinguishable from a monolingual native speaker of the ‘standard variety’ is commonly believed to be the aim of most (if not all) additional language learners (see Chapter 2). This assumed aim continues to exert a strong influence over the hiring practices, pay structure, marketing, materials selection and testing regimes of additional language education around the world, despite what we know from linguistics about: the lexico-grammatical and phonological variation within all languages (depending on the age, location, job, hobbies, religion, ethnicity, subculture, gender, etc. of the speaker); the absence of an accent-free version of any language; variation within individual speakers (depending on their role in the conversation and their relationship with their interlocutor); and the extent to which multilingual speakers sometimes mix their languages and varieties for maximum communicative effect.

In an effort to more accurately reflect this speaker- and situation-dependent variation, Constant Leung, Roxy Harris and Ben Rampton (1997) suggest that the idea of monolithic native-speakerism be finessed by consideration of speakers’ linguistic repertoire in terms of: expertise (the ability to achieve specific tasks in specific situations);inheritance (the age at which a language in the repertoire began to be used, under what circumstances it was learned); and affiliation (level of comfort in using the language, feelings of belonging to a community of language speakers). Vivian Cook (1993) points out that the whole point of learning a new language is to add to an existing linguistic repertoire, that is, to achieve communicative goals in new situations for which the languages in the existing repertoire would be unsuitable or not ideal. Psycholinguistic research shows us that the original languages continue to exist in the learner’s mind alongside the new language as an interconnected system, and are jointly activated in multilingual situations. Thus, even under the most ideal circumstances, the goal of native-speakerness is likely to be an irrelevant and reductive one for learners who have needs for different kinds and levels of expertise in their different languages.

Native-speakerism is the rarely challenged assumption that the desired outcome of additional language learning is, in all cases, ‘native’ competence in the ‘standard’ variety, and that native speakers have, therefore, an inbuilt advantage as teachers of the language. ‘Nativeness’ is also often conflated with nationality (note the ambiguity of German, Chinese, etc.), but since national borders are not consistent with linguistic ones, the geography-based native/second/ foreign typology is problematic as a system to classify language learners and teachers.

The Benefits of Learning an Additional Language

Caxton’s introduction to his fifteenth century English–French phrasebook (from which we took the epigraph for this chapter (p. 197)) suggests that language learners may profit by being better able to buy, sell and transport goods internationally – an early form of languages for international business. Today, depending on who and where you are and the language you are learning, the benefits might include: meeting new people; being accepted into a university; getting a job or promotion; sounding like an intelligent, sophisticated person; or, in the case of immigrants and language minorities, access to formal education or simply survival.

Although some of these benefits are impossible to measure, language economists have attempted to explore the possible financial benefits of having an additional language. In Switzerland, for example (where less than 1 per cent of the population speak English as a first language), research has demonstrated a strong, positive link between an individual’s earnings and their English language skills (Grin, 2001). However, other factors, such as type of job and other languages spoken, were important intervening variables: people in export-oriented jobs showed the greatest benefits, and German was more valuable than English for individuals who spoke French as a first language.

It seems likely that where speaking an additional language is considered part of a ‘good’ general education it is the demonstration of this ‘good’ education through additional language qualifications which ‘causes’ higher earnings, rather than proficiency itself. It is also possible that higher earnings create more chances for language learning (travel or a more ‘international’ job), suggesting that financial benefits might well ‘cause’ language learning, and not the other way round.

As with all other skills or qualifications, the advantage of an additional language may decrease as more and more individuals acquire the same skill. So, is learning an additional language likely to provide a good return on your investment? The answer depends on a number of factors, including what you want to achieve, what your job is, where you are and the level of skills in the pool of people you are competing with. Of course, this assumes a completely rational market for language skills. Sadly, the value of your languages probably depends more on the attitude of potential employers to the languages you speak (are they considered ‘useful’, or prestigious in some other way) and on their general attitude to you or the group they see you as representing.

Teaching Language Varieties

As we saw in the introduction to this chapter (p. 197), the question of which variety of an additional language to teach is one which is increasingly debated. Regional and social variation within languages has, of course, always existed. But the spread of languages of wider communication such as Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French and English through colonialism, migration and diffusion of new technologies has resulted in the development of a wide variety of norms to satisfy local communicative needs in different geographical settings. This profusion of varieties, and the endless possibilities for mixing with other languages already spoken by local users, does not, as might have been feared, seem to have created problems for interaction outside local contexts. On the contrary, the more linguistic resources a user has at her disposal and the greater her experience of monitoring and accommodating the language proficiency and choices of her interlocutors, the better she may be at communicating in an variety of social, regional and global contexts (Canagarajah, 2007). In fact, it has been suggested that being a monolingual speaker of even a widely used language may turn out to be a disadvantage (Smith, 1983; Rajagopalan, 2004).

How can teachers of languages of wider communication respond? Options include:

reflecting on which varieties of the language their students are most likely to need, and want, to use;

reflecting on which varieties of the language their students are most likely to need, and want, to use;

exposing students to a wide range of varieties to give them practice in accommodating differences in accent, lexicon, grammar and discourse strategies, as advocated in World Englishes and English as a lingua franca approaches to English teaching (for example Kirkpatrick, 2007; Matsuda, 2006);

exposing students to a wide range of varieties to give them practice in accommodating differences in accent, lexicon, grammar and discourse strategies, as advocated in World Englishes and English as a lingua franca approaches to English teaching (for example Kirkpatrick, 2007; Matsuda, 2006);

using dictionaries, grammar books and corpora that represent different varieties of the language;

using dictionaries, grammar books and corpora that represent different varieties of the language;

using world literature, popular music, TV and the internet as sources of texts for reading, listening, and presenting and practising varieties of the additional language;

using world literature, popular music, TV and the internet as sources of texts for reading, listening, and presenting and practising varieties of the additional language;

asking students (to think) about the varieties they are already using and/or aiming to use, and who they plan to use them with.

asking students (to think) about the varieties they are already using and/or aiming to use, and who they plan to use them with.

For an example of an awareness-raising activity that aims to draw students’ attention to how they communicate in mixed language groups, see Wicaksono, (2009).

Additional Language Learning and Identity

Early work that proposed a role for the learner’s identity in the language learning process (for example Gardner and Lambert [1972] on instrumental and integrative motivation) tended to characterize identity as a fixed product of the relationship between an inherited language and culture, located in the mind of a learner. More recently, identity has been re-characterized as a more fluid process of a learner’s actions and beliefs acting on, and being acted on by, his/her various situations and experiences (Norton, 2000). Allocating other people to groups can be an attempt to understand, manage (with their knowledge and consent) or control them (without their consent, and with or without their knowledge). Claiming or resisting a group identity can be an attempt to understand or manage others’ impressions of oneself or take control over others.

An example of the allocation of identity is the effect of placing learners in classes based on their score in a target language proficiency test; subsequently a certain standard of proficiency will be expected by their teacher and variations from the target variety will be judged against ‘what they should know by now’. Their opportunities to benefit from the input of more proficient students may thus be limited and they may be judged to be ‘not ready’ for specialist vocabulary or certain authentic texts. These same intermediate learners may not attempt to pronounce certain sounds that they feel make them look ‘uncool’ in front of their peers, or they may experiment with colloquial language when interacting with peers in the target-language community. The point is, the way a learner identifies with an additional language will depend on how, when, where and why she learned (or is learning) it and the assumptions that are made about her by the people she associates with.

In work by Celia Roberts, Michael Byram and their colleagues (Roberts et al., 2001), university students of languages trained to become ‘ethnographers of language’ in preparation for study abroad experiences. The authors suggest that teachers interested in raising the issue of additional language effects on learner identities can consider encouraging their learners to: notice a variety of styles (register, genre, sociocultural variation) in the target situations they are preparing for; discuss how their languages can be mixed to achieve certain effects in some situations; reflect on how other people, both inside and outside the class, respond to their use of the target language; and consider how ‘signs’ other than their use of language (clothes, ethnicity, facial expressions, gestures, gaze, stance, etc.) are responded to by others.

Culture in the Classroom

Culture is a product of both society and the processes or sets of actions by which society creates, maintains and transforms itself. Culture is something we ‘do’, and therefore appears to be something we ‘have’, but does it therefore follow that it is possible to talk about monolithic ‘cultures’? Describing the culture of the Indian subcontinent (or Sri Lankan culture, or Tamil culture, or Tamil student culture, or the culture of agricultural students at the Eastern University in Vantarumoolai, Sri Lanka) requires us to notice, select and prioritize differences between people. What we notice, select and prioritize depends on our situation, current activity, time and what we are making important now.

Having said all this, additional language education has generally presented culture as a product, rather than a process; something that is internally consistent and fixed, that ‘belongs’ to the speakers of the language being taught. Thus, languages are often conflated with ‘national cultures’, when, for example, English is associated uniquely with ‘British’ or ‘American’ culture and Mandarin is seen as reflecting ‘Chinese’ culture. This product-based approach to culture in the language classroom typically takes the form of ‘representative topics’ – aspects of ‘the culture’ that are considered by the teacher or syllabus designer to be useful, important, attractive or different from the culture of the learner. Here are a couple of examples of this ‘representative topics’ approach to culture:

A British university course for pre-undergraduate students called ‘British Culture and Society’: Food (fish and chips, roast beef and Yorkshire pudding), Government (three main political parties, ‘first past the post’ voting system), Sport (rugby, cricket), Media, Health, etc.

A British university course for pre-undergraduate students called ‘British Culture and Society’: Food (fish and chips, roast beef and Yorkshire pudding), Government (three main political parties, ‘first past the post’ voting system), Sport (rugby, cricket), Media, Health, etc.

A textbook for Indonesian children in West Java learning Sundanese, the regional language, at primary school: Inside the House (cassava, stinking bean, fermented cassava, bucket, duck, satay, chair, table, cupboard, potted plant, television, radio, bookshelf, shoes, ashtray, umbrella, etc.).

A textbook for Indonesian children in West Java learning Sundanese, the regional language, at primary school: Inside the House (cassava, stinking bean, fermented cassava, bucket, duck, satay, chair, table, cupboard, potted plant, television, radio, bookshelf, shoes, ashtray, umbrella, etc.).

While this approach to culture in the language classroom can be interesting for learners, it can also:

over-generalize and over-emphasize difference (how often does a UK household eat roast beef and Yorkshire pudding or a Sundanese household eat fermented cassava? In Britain curry (any vaguely spicy dish) is more often eaten than roast beef, and Sundanese families probably eat just as many packets of dried noodles as any other Indonesian family);

over-generalize and over-emphasize difference (how often does a UK household eat roast beef and Yorkshire pudding or a Sundanese household eat fermented cassava? In Britain curry (any vaguely spicy dish) is more often eaten than roast beef, and Sundanese families probably eat just as many packets of dried noodles as any other Indonesian family);

under-generalize and disguise interesting regional, class and age group differences, as well as changes over time;

under-generalize and disguise interesting regional, class and age group differences, as well as changes over time;

be a way of promoting a particular impression of the additional language speakers (by sticking to certain attractive topics and avoiding others, or vice versa, depending on the power relations between the community of additional language learners and those who speak the additional language as a first language);

be a way of promoting a particular impression of the additional language speakers (by sticking to certain attractive topics and avoiding others, or vice versa, depending on the power relations between the community of additional language learners and those who speak the additional language as a first language);

be a way of justifying unequal teacher employment conditions (for example paying a French national more to teach French in Sri Lanka than an equally competent and qualified Sri Lankan).

be a way of justifying unequal teacher employment conditions (for example paying a French national more to teach French in Sri Lanka than an equally competent and qualified Sri Lankan).

So, if a language teacher wants to raise her students’ awareness of ‘culture’ but go beyond a superficial and inherently misleading ‘list of things you need to know about the speakers of language A’ approach, what can she do? Claire Kramsch (1993) lists ways in which teachers have tried to help students make sense of the new possibilities and challenges that an additional language may offer, including:

discussing whether differences between groups and individuals will diminish as the interconnectedness of the world’s economies (globalization) increases;

discussing whether differences between groups and individuals will diminish as the interconnectedness of the world’s economies (globalization) increases;

increasing opportunities to experience cultural difference by encouraging student exchanges across national boundaries;

increasing opportunities to experience cultural difference by encouraging student exchanges across national boundaries;

giving greater attention to ways in which we are all affected by international migration and the spread of information technologies;

giving greater attention to ways in which we are all affected by international migration and the spread of information technologies;

raising awareness of the language and behavioural factors that can lead to people being judged as ‘foreign’, as well as how these judgements will be applied to them and whether they want to (or are able to) do anything to change the way they are judged.

raising awareness of the language and behavioural factors that can lead to people being judged as ‘foreign’, as well as how these judgements will be applied to them and whether they want to (or are able to) do anything to change the way they are judged.

The last point on the list above brings us back to our original definition of culture at the beginning of this section. In addition to (or instead of) having culture presented as something they ‘have’, language learners can also consider how culture is something they ‘do’ (and have done to them). Encouraging learners to focus on the process of doing the various cultures they belong to could involve, for example, noticing (and perhaps making an audio recording of – with the permission of the people being recorded) when and how they and other people:

mix languages;

mix languages;

slow down, simplify, rephrase something they have said, use (or consciously avoid) slang or jargon, alter their accent to match the person they are talking to;

slow down, simplify, rephrase something they have said, use (or consciously avoid) slang or jargon, alter their accent to match the person they are talking to;

use more, fewer or different gestures, nod, smile, back channel (‘yeah, right’, ‘uh huh’) or listen in silence, make or avoid eye contact;

use more, fewer or different gestures, nod, smile, back channel (‘yeah, right’, ‘uh huh’) or listen in silence, make or avoid eye contact;

take responsibility for starting a new topic of conversation, interrupt, pause, talk a lot, mainly listen, abandon a topic;

take responsibility for starting a new topic of conversation, interrupt, pause, talk a lot, mainly listen, abandon a topic;

ask for clarification, agree and disagree, correct (or ignore) their own or others’ language ‘mistakes’;

ask for clarification, agree and disagree, correct (or ignore) their own or others’ language ‘mistakes’;

say that they dislike or like the way that someone else speaks, say that they think they are a better or worse communicator than the person they’re speaking to.

say that they dislike or like the way that someone else speaks, say that they think they are a better or worse communicator than the person they’re speaking to.

9.6 Roles for Applied Linguists

Applied linguists can contribute to the area of additional language education by doing any or all of the following:

maintaining a critical stance, involving an awareness of the social, political, economic and commercial contexts of additional language learning, and how these might affect why, how and what students learn;

maintaining a critical stance, involving an awareness of the social, political, economic and commercial contexts of additional language learning, and how these might affect why, how and what students learn;

keeping up to date with major trends and new ideas in the theory of second language acquisition;

keeping up to date with major trends and new ideas in the theory of second language acquisition;

collaborating with applied linguists in other fields and developing an awareness of their aims and methods, especially language pathologists, educators working in literacy and bilingual environments, translators and lexicographers;