Chapter 2

Correct spelling, correct punctuation, correct grammar. Hundreds of itsy-bitsy rules for itsy-bitsy people.

(Robert Pirsig, 1974)

Most of the ‘dead ends’ discussed in Chapter 1 are rooted in our unfortunate inability to recognize that languages always exist in a multitude of forms. We see them as single objects, like rocks, but they are in fact more like sandy beaches, rain clouds or galaxies: collections with no one central point and no sharply defined borders. Our misperception leads to firmly held beliefs about how language(s) may be used and abused, and to intractable positions when these beliefs are questioned or threatened. But it’s a palpable fact that we don’t all speak the same way, even when we happen to share what we regard as the same language. The variation in and between languages has profound but often hidden consequences for the whole spectrum of enterprises we call applied linguistics, only some of which have begun to be understood and revealed. In this chapter we look more closely at the notion of language variation and varieties, asking how some of them come to be regarded as ‘standard’ while others are viewed as ‘non-standard’ or even ‘incorrect’. We’ll also address the distinction between native and non-native varieties of a language, and issues of language authority and linguistic insecurity. Implicit in all this are underlying issues of power, prestige and identity, making language variation one of the thorniest issues applied linguists deal with.

World Englishes refers to the phenomenon of English as an international language, spoken in different ways by perhaps one-third of the world’s population spread across every continent. The term also indicates a view of English which embraces diversity and questions the assumption that contemporary native speakers have inherent stewardship of, or competence in, the language.

The chapter is organized as follows. In the opening sections we tackle the ‘monolithic myth’ which dominates folk belief, namely that there is, or ought to be, one correct, standard language, from which departure is inevitable but lamentable. We discuss the identification of variation in language with the social construction and valuation of one’s own and especially others’ identities in section 2.1, and briefly illustrate the main dimensions of monolingual variation in 2.2. We then turn to the process of standardization and the distinction between ‘standard’ and ‘non-standard’ varieties in 2.3. Of particular interest to many applied linguists, and increasingly relevant in our ever more globalized world, is the newly contested ground of ‘non-native’ varieties, and this is the focus of 2.4, where the topic of World Englishes is introduced as a strand which will be developed throughout the book. The notion of linguistic insecurity, fostered by ideologies of intolerance for language variation, is discussed in 2.5, and its role in the very survival of linguistic diversity is stressed. In the last couple of sections, we present an applied linguistic view of variation as a function of situated practice (2.6) and close with a comment on what we think may be the key responsibility for all applied linguists (2.7).

2.1 Language Variation and Social Judgement

In introductory linguistics classes around the world, first-year students undergo the ritual process of what we might call de-prescriptivization (or, more candidly, ‘linguistic reprogramming’). Outside linguistics and applied linguistics, the unquestioned assumption is that there is one form of the language(s) of the state, the so-called ‘standard’ form, variation from which may be inevitable but is generally undesirable and must be kept in check. It is the job of schools and other (official or self-appointed) guardians to prescribe the ‘standard’ forms and proscribe the ‘non-standard’ ones. Rather perversely to some lay commentators, general linguistics seeks to describe linguistic systems and how they vary through space, time and context, without judging the so-called ‘varieties’ corresponding to each different system. Routinely, the process of de-prescriptivization is at most only a partial success, and more often it fails completely. We introduced in Chapter 1 the notion of the Language Spell (Hall, 2005) as a metaphor for our incapacity to penetrate the sociocognitive reality of language: that it’s actually located in six billion brains, interacting in dynamic and fluid communities, and not in a few thousand grammar books, dictionaries and usage guides. We are normally impotent before the power of the Spell, and even when we do become aware of it, as students of linguistics (and linguists ourselves), it tests us mightily. Take, for example, English in England: the almost universally held belief is that there is one English language, against which other national varieties (spoken in the USA, Australia, Scotland, etc.) are measured and (mostly) tolerated; in comparison with which regional dialects are treasured, ridiculed or deplored; and foreigners’ attempts to reproduce which are judged correct or (more often than not) wrong (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 ‘Standard British English’ and some varieties supposedly deriving from or dependent on it

This is the myth of ‘Monolithic English’ (Hall, 2005, p. 252; Pennycook, 2007), which we can summarize in the following two folk maxims:

‘the’ English language is a monolithic social entity, characterized by the ‘standard variety’ spoken by educated native speakers;

‘the’ English language is a monolithic social entity, characterized by the ‘standard variety’ spoken by educated native speakers;

English learners learn and English teachers teach ‘the’ English language, analogous to the way ‘proper’ table manners may be learned, taught and prescribed.

English learners learn and English teachers teach ‘the’ English language, analogous to the way ‘proper’ table manners may be learned, taught and prescribed.

The power and pervasive damage of the myth can’t be underestimated. It underlies our conceptions of social value and the power of class and privilege. The quotation from Robert Pirsig about the pettiness of ‘correct English’ in the epigraph on p. 25 continues as follows:

It was all table manners, not derived from any sense of kindness or decency or humanity, but originally from an egotistic desire to look like gentlemen and ladies. Gentlemen and ladies had good table manners and spoke and wrote grammatically. It was what identified one with the upper classes.

(Pirsig, 1974, p. 183)

And with the educated, reading classes, who should know better: in a letter to a newspaper, a North Carolinian upset with the linguist Walt Wolfram’s recommendations to teachers working with language minority children, fulminated: ‘To not know the forms of proper English usage is ignorance; to know and then still not use them because of your desire to be “culturally diverse” is attempted murder upon the English language’ (quoted in Wolfram et al., 1999, p. 30). The effects of the monolithic myth and the associated belief in a ‘standard’ language are so much more important than the effects of bad table manners, as the next section, on authority in language, shows.

Authority in Language

The notion of language standards is closely tied to the notion of public or private ‘authorities’ that set and seek to maintain those standards, however arbitrary and far from the ‘linguistic facts’ they may be. Such efforts are typically not really about language at all, but rather about establishing or protecting the power of a group through the language or variety they speak. The monolithic myth underlying such efforts holds that language is essentially a static entity rather than a dynamic system which is capable of – indeed, dependent on – constant change and diversification. Policies and recommendations by language academies to exclude foreign words from public use, and workplace language policies promoting one language over others, are essentially attempts to gain or maintain power and control over individuals and groups who are perceived as threatening and whose language or variety is thus a target for public criticism and even legislation. Like Ron Unz, the anti-bilingual education activist in the US, language authorities are often self-nominated, legislating norms for the rest of us. Rosina Lippi-Green (1997, p. 73) describes how rules about ‘standard’ language can be used to justify restrictions on less powerful peoples’ individuality and their right to participate on equal terms, and calls the criticism of some accents ‘the last back door to discrimination’ (see section 2.2 below for more on accent). She describes a process of language subordination by which certain varieties become thought of – even by the people who speak them – as ugly or illogical or incoherent. The process operates, she argues, through the repetition of messages in the education and judicial systems (Table 2.1), the broadcast and print media, the entertainment industry and the corporate sector (Lippi-Green, 1997, p. 68).

Table 2.1 Lippi-Green’s ‘language subordination model’ (Source: adapted from Lippi-Green, 1997, p. 68)

Language subordination process |

Message |

Language is mystified |

You can never hope to comprehend the difficulties and complexities of your mother tongue without expert guidance. |

Authority is claimed |

Talk like me/us. We know what we are doing because we have studied language, because we write well. |

Misinformation is generated |

That usage you are so attached to is inaccurate. The variant I prefer is superior on historical, aesthetic or logical grounds. |

Non-mainstream language is trivialized |

Look how cute, how homey, how funny. |

Conformers are held up as positive examples |

See what you can accomplish if you only try, how far you can get if you see the light. |

Explicit promises are made |

Employers will take you seriously; doors will open. |

Threats are made |

No one important will take you seriously; doors will close. |

Non-conformers are vilified or marginalized |

See how willfully stupid, arrogant, unknowing, uninformed and/or deviant and unrepresentative these speakers are. |

And even linguists fall for the myth, or at least fail to acknowledge the difficulties associated with it. In his pivotal work Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, for example, Noam Chomsky (in)famously posited ‘an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogenous speech-community, who knows its language perfectly and is unaffected by … grammatically irrelevant conditions … in applying his knowledge of the language in actual performance’ (Chomsky, 1965, p. 3). Accounts of English and other languages in Chomskyan theoretical linguistics are largely constructed from data sets which really don’t represent the rich linguistic resources deployed by the majority of their speakers spread across vast heterogeneous networks of user groups and uses. The ‘intuitions of grammaticality’ collected to form data sets for analysis (by asking questions such as ‘How does John’s seeming to be intelligent sound to you?’) are provided by educated language users whose deliberate judgements are naturally and inevitably constrained by socialization processes. In the case of English at least, these processes are the cultural legacy of centuries of explicit and implicit privileging of certain ways of using and thinking about language, especially as it’s been codified through written texts.

Grave as these methodological shortcomings may be, however, it’s unwise to dismiss Chomsky’s mentalist approach to language out of hand. An acknowledgement of the cognitive basis of linguistic systems requires the kind of descriptive detail and theoretical rigour that will allow accounts of language to be compatible with theory in cognitive neuropsychology, as applied, for example, to language disorders like aphasia (see Chapter 13). Such an approach can provide sophisticated tools to explore variation between individuals, and some descriptive linguists following the Chomskyan tradition use dialect and ‘non-standard’ data as a matter of course (e.g. Henry, 1995; Green, 1998; Kayne, 2000; Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008, ch. 3). Others specifically highlight the potential contribution of Chomskyan theory to an understanding of ‘socially realistic linguistics’ (Wilson and Henry, 1998). But for the most part it has been sociolinguists who have focused on variation within a language, albeit concentrating on the level of groups, rather than individual minds. One of the pioneers of modern sociolinguistics, William Labov, acknowledged the theoretical and empirical richness of Chomsky’s approach, while exposing its methodological limitations (e.g. Labov, 1972, ch. 8). He even attempted to modify Chomskyan-style grammatical rules by incorporating probabilities of occurrence as influenced by non-linguistic variables (such as gender and class). But this notion of ‘variable rule’ proved to be ultimately unworkable in the opinion of most sociolinguists (Wardhaugh, 2006, p. 187). The work of Labov and others extending linguistic theory beyond the analytical ideal of homogeneity in the speech community has had a profound influence on the development of applied linguistics, and underlies much of the thinking mapped out in the chapters to come.

Language Judgements

Linguists’ use of the term variety (e.g. Ferguson, 1971) to describe a linguistic system shared by a geographically or socially defined group (covering both dialect and language) reflects the centrality of the notion of variation in language study. For prescriptivists, the term ‘standard variety’ must look like quite an oxymoron, given that standard suggests an accepted norm but variety suggests that languages come in different versions. Furthermore, the word variety suggests, and rightfully so, that the standard is really just another dialect, at least linguistically speaking. In Chapter 1 we said that the notion of a single standard version of a language is a dead end for applied linguists, but it remains a powerful one in the minds of language users. Thus, while the differences between varieties can be empirically described by linguists, users imbue these differences simultaneously with two fundamentally different forms of meaning: linguistic and social significance. Here is an example of these different interpretations, based on a fragment of a variety that greatly surprised one of the authors who as a child moved from the Midwestern state of Michigan to Maine in New England on the East Coast of the USA.

In linguistics, a variety refers to the systematic ways in which an identified group of speakers uses a language’s sounds, structures and senses. The term allows linguists to recognize the distinctiveness of a group’s shared linguistic system and usage, without making claims about its status as a ‘full language’ or ‘just a dialect’.

| Smith: | I really liked that movie. |

| Maine resident: | So didn’t I. It was wicked good. |

Like the young Smith, readers unfamiliar with this variety can probably negotiate the unfamiliar linguistic expression and understand that the Maine resident here is actually agreeing with Smith that the movie was a good one rather than expressing disagreement. Embedded in non-linguistic and other contextual clues, this example of ‘non-standard’ use of didn’t doesn’t cause any breakdown in communication. As is typical of instances of intralinguistic dialect contact, speakers work out the message without much difficulty. Note another question raised by such contact: just who is speaking with appropriate norms here? The young Smith, whose usage may be closer to the variety this book is written in, or his counterpart, into whose linguistic territory Smith has just moved? Thus, we could argue that all varieties function as the standard (the norm for the context) somewhere, usually in the geographic location(s) or social contexts in which the speakers who speak them are situated, but also in text-types or in cyberspace.

At the same time as speakers successfully negotiate a linguistic message, we are also unconsciously assigning social meaning. In the case of our ‘wicked good’ moviegoers, the Maine resident may have wondered why Smith sounded like a teacher or someone on the television news, and Smith no doubt formed some opinions of his own about his interlocutor’s social background and identity. If the teenage Hall and Wicaksono were to join the conversation at this point, speaking about films as opposed to movies, the other kids might assign them class- and education-related identities based solely on their ‘posh’ or ‘cool’ British accents. Such judgements, based on the ways people talk, result in hearers’ constructions of identity, which the speakers themselves may or may not share, and which are often informed by general stereotypes. Recall Preston’s words from p. 9:

Some groups are believed to be decent, hard-working, and intelligent (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be laid-back, romantic, and devil-may-care (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be lazy, insolent, and procrastinating (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be hard-nosed, aloof, and unsympathetic (and so is their language or variety), and so on.

(Preston, 2002, pp. 40–41)

Received Pronunciation (RP) is a way of pronouncing English which emerged in the late nineteenth century as the accent of England’s privileged classes. It is considered by many to have very high prestige and is still used as a target for teaching and a benchmark for phonetic description of other accents, despite its rarity.

The words we use, the way we pronounce them and the way we string them together have far-reaching social significance, leading to swift and often very harsh judgements not only of individual identity but of situational appropriacy (see the sub-section on register variation on p. 35). Take taboo words, for example. An iconic national ritual on the BBC’s prestigious Radio 4 in the UK is the marking of the hour with three pips, preceded by a solemn continuity announcement spoken in solid Received Pronunciation (RP). In 2009 the seasoned professional Peter Jefferson was reported to have lost his job after mixing up his words and saying the ‘F-word’ during the sacred pips (Adetunji, 2009). This particular word (otherwise written as f**k) is fast losing its taboo status in many English-speaking social groups (it does, for example, appear in the national newspaper article where we read about the story); but its use can still cause shock and/or offence if uttered in the wrong social context or by the wrong person, as our example illustrates. We will be using a word from the f**k family later in this chapter and in future chapters, but for purely scientific purposes, so we hope no offence will be taken.

That the way a person uses language is such a powerful factor in social judgements has been neatly demonstrated by the ‘matched guise’ technique, originally employed in Canada by Wallace Lambert. Lambert had been struck by the judgements people made about the language choices and uses of others in bilingual Montreal. In an early article summarizing the technique, Lambert shared an anecdote about his twelve-year-old daughter to illustrate how strong language attitudes can be and how sensitive we are to them, from a very early age. After they have stopped to pick up one of her friends on the way to school, she excitedly tells her father not to pick up a second friend they subsequently encounter:

At school I asked what the trouble was and she explained that there actually was no trouble although there might have been if the second girl, who was from France, and who spoke another dialect of French, had got in the car because then my daughter would have been forced to show a linguistic preference for one girl or the other. Normally she could escape this conflict by interacting with each girl separately, and, inadvertently, I had almost put her on the spot.

(Lambert, 2003 [1967], p. 306)

On the basis of such experiences, Lambert developed a technique for assessing attitudes to language varieties by having people judge the speaker of utterances spoken in different accents or languages on traits such as sincerity, intelligence, friendliness and confidence. Unbeknownst to the judges, the utterances were produced by a single voice, that of a bidialectal or bilingual actor. In the UK, Howard Giles used the technique to assess attitudes to regional accents of English. Although there are drawbacks to the technique (cf. Agheyisi and Fishman, 1970), the results are consistent and striking. In a series of studies, Giles and colleagues showed how accents in the UK were regularly associated with stereotypical regional characteristics, with the use of ‘standard’ forms like RP normally judged more positively than that of ‘nonstandard’ forms like Brummie (from Birmingham) or Cockney (from London) (Giles and Billings, 2004).

2.2 Kinds of Variation

Accent

Perhaps the most immediate and overt parameter of variation in language is its principal external modality, either speech or sign. Babies perceive speech or sign before they understand and produce it in structured ways. When you’re exposed to a language you don’t know, all you get is the speech sounds or signs, not the sense they are intended to communicate. It is speech and sign which make languages observable; you can’t perceive grammar or semantics. Variation at this level is largely a matter of accent, and we all have one (including signers: see, for example, Johnston and Schembri, 2007). Lippi-Green likens the development of accent to the construction of a house to live in. Although all hearing children are born with the ability to acquire the phonology of any language variety, the immediate environment inevitably determines the system they build:

At birth the child is in the Sound House warehouse, where a full inventory of all possible materials is available to her. She looks at the Sound Houses built by her parents, her brothers and sisters, by other people around her, and she starts to pick out those materials, those bricks she sees they have used to build their Sound Houses … [She] starts to socialize with other children. Her best friend has a slightly different layout, although he has built his Sound House with the exact same inventory of building materials. Another friend has a Sound House which is missing the back staircase. She wants to be like her friends, and so she makes renovations to her Sound House. It begins to look somewhat different than her parents’ Sound Houses; it is more her own.

(Lippi-Green, 1997, pp. 46–47)

The child settles into an accent which is not identical to those of her parents or friends, but extremely similar to them. For example, many young people from the east of Yorkshire in England share with their parents a distinctive pronunciation of the vowel sound /o/ in words like foam or both, such that they sound to other British English speakers like firm and the French word boeuf, respectively. But some young speakers from the same communities have picked up an innovation from the south of England, known as th-fronting, whereby words like thin are pronounced the same as fin, and writhe the same as rive (with ‘th’ consonants produced at the front of the mouth). So a young person from this area might pronounce both with their parents’ vowel and their peers’ final f. Young people regularly move to or between different groups and can operate with different phonologies, sometimes losing, sometimes maintaining them. Lippi-Green continues:

Maybe she [becomes] embarrassed by [her] A[frican] A[merican] V[ernacular] E[nglish] Sound House and never goes there anymore, never has a chance to see what is happening to it. Maybe in a few years she will want to go there and find it structurally unable to bear her weight.

(Lippi-Green, 1997, p. 47)

The phonology of a spoken language is the system of sounds that it uses, both individual units consonants and vowels) and combinations of these units (stress and intonation). The phonology of a sign language is the system of manual and facial gestures that it employs.

Taken together, the different accents within and across individuals and groups reflect the degree of variation in the phonology of their language.

Dialectal Variation

A dialect is a variety of a language determined normally by geographical and/or social factors. The term is normally used in the context of languages which have been extensively documented and have a recognized ‘standard’ dialect against which others are compared.

Morphology is the systematic patterning of meaningful word parts, including prefixes and suffixes.

People sometimes confuse dialect with accent. But from a linguistic perspective, accent is just one of several features that distinguish one variety from another; vocabulary, syntax and morphology are other features of language that vary across groups of speakers. Dialects, then, include accent, and linguists use the term to refer to varieties that share with others sufficient linguistic elements for them to be called a single language. So, many varieties of Scottish English, for example, are perfectly intelligible to speakers of other varieties spoken outside of Scotland, even though they vary in accent, vocabulary and syntax. An example of lexical variation in Scottish Englishes is the use of outwith as a preposition meaning ‘outside’, as in this example from the British National Corpus:

there is already a determination that schools outwith Scotland’s central belt should be the beneficiaries.

Just as everyone has an accent, so too everyone has a dialect. The ‘standard’ is just one among others. Outwith linguistics, the term is normally used for ‘non-standard’ regional varieties: the ‘ugly’, ‘quaint’ or ‘comic’ ways that urban underclasses or rustic peasantry speak. But speech communities are not only determined by region. Just as Lippi-Green’s Sound House builder starts her phonology at home with the family and then adjusts it when she moves outside to participate in larger social groupings, so she builds a new grammar and lexicon which reflect her age group and lifestyle choices.

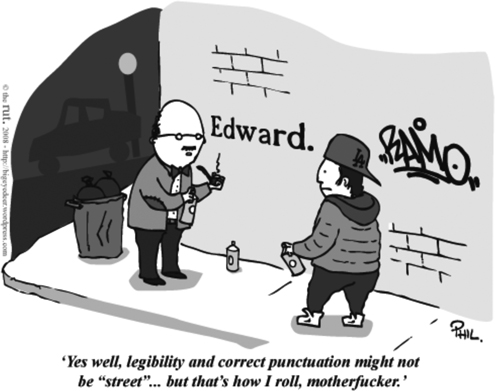

The cartoon in Figure 2.2 reflects non-linguists’ awareness of social dialects, especially how linguistic stereotypes (word choice, writing style and literacy practices) dovetail with stereotypes about age, dress and behaviour. The humour of the cartoon stems from its overlapping sets of parallel incongruities between language form and language practice:

Figure 2.2 How language is perceived as correlating with age, dress and behaviour (copyright Philip Selby)

This strong connection between dialect and non-linguistic group identity is seen especially clearly at the level of ‘nation’, where dialects associated with national identities regularly get called languages in their own right, despite their mutual intelligibility with other dialects beyond the national borders. So, for example, there is Dutch in the Netherlands, called Flemish in Belgium; Hindi in India, called Urdu in Pakistan; Norwegian, Swedish and Danish in Scandinavia, but basically varieties of the same language. Within nation states, dialects of the majority language spoken by minority groups with power are often recognized as languages, whereas those of other significant minorities without power remain dialects. For example, Scots, which is claimed as a separate language from English in Scotland, is no more unintelligible to speakers of neighbouring ‘Geordie’ than African American English is to speakers of Mexican American English. Scots gets more legitimacy as a language because Scotland is a proud nation in its own right within the UK, whereas African American English is the stateless dialect of a relatively powerless minority group.

A particularly notorious case is that of the Catalan and Valencian translations of the proposed EU Constitution, submitted to the European Commission by the Spanish government in 2005. The linguistic legacy of the Roman invasion of the Iberian peninsula over two millennia ago resulted in a broad spectrum of related languages, all the way from Portuguese in the south-west to Castilian, the national standard of Spain, in the centre, and to Galician and Catalan in the semi-autonomous regions of the north-west and north-east. After the forty-year fascist dictatorship of Franco in Spain, in which the linguistic minorities were brutally oppressed, most regions achieved a significant degree of autonomy, leading to the official recognition of their languages. Valencian is quite clearly a sister variety of Catalan, but Valencia is a major regional player, and when its authorities failed to reach agreement with neighbouring Catalonia on norms for their shared language, Catalonia decided to submit the Valencian version of the constitution as its own, as a sign of common political cause with Valencia, as the national daily El País reported (Valls, 2004). From Table 2.2 you can appreciate why eyebrows were raised in Brussels, and anger and embarrassment was felt in different parts of Spain, when the central government in Madrid submitted ‘both’ versions, along with Galician, Basque and Castilian (Maragall rectifica …, 2004).

Table 2.2 Excerpts from the Valencia and Catalan versions of the EU Constitution

Catalan |

Valencian |

La present Constitució, que naix de la voluntat dels ciutadans i dels Estats d’Europa de construir un futur comú, crea la Unió Europea, a la qual els Estats membres atribuïxen competències per a assolir els seus objectius comuns. La Unió coordinarà les polítiques dels Estats membres encaminades a assolir estos objectius i exercirà, de forma comunitària, les competències que estos li atribuïsquen. |

La present Constitució, que naix de la voluntat dels ciutadans i dels Estats d’Europa de construir un futur comú, crea la Unió Europea, a la qual els Estats membres atribuïxen competències per a assolir els seus objectius comuns. La Unió coordinarà les polítiques dels Estats membres encaminades a assolir estos objectius i exercirà, de forma comunitària, les competències que estos li atribuïsquen. |

The flip-side of this dialect–language jousting between powerful players is the widespread disparagement of what are clearly languages by calling them dialects. In Peru, for example, the education ministry only considers Ashaninka, Awajún, Shipibo and Quechua as languages; other Indigenous languages are treated as dialects, and not considered worthy of their own curriculum or textbooks (see Chapter 14 for more on this point).

There is also a great deal of authentic variation in the ways a single speaker uses the linguistic resources at their disposal. Imagine for a moment a bailiff in family court, paying close attention to the proceedings. His friend the clerk is reading legal papers and she has momentarily lost the plot. She whispers to the bailiff to find out what she has missed. The bailiff tells her, soto voce, that

They’ve asked what the other guy thinks ’bout the kid.

If we rewind the scene and replace the clerk with a judge, however, the bailiff might give her the same message using very distinct linguistic encoding:

A second professional opinion regarding the infant has been requested by counsel, Your Honour.

A register is a way of using the language in certain contexts and situations, often varying according to formality of expression, choice of vocabulary and degree of explicitness. Register variation is intrapersonal because individual speakers normally control a repertoire of registers which they deploy according to circumstances.

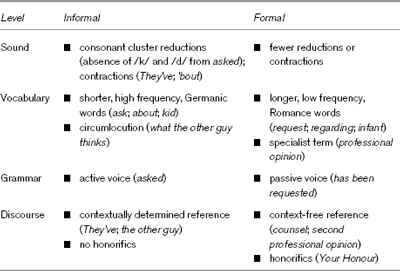

The style of the first is informal and concise, relying on shared knowledge and reflecting greater intimacy. The second is much more formal and elaborated, taking little for granted and explicitly encoding the power relations. Linguists use the term register to refer to an individual’s styles as they vary with situation and interlocutor. Table 2.3 summarizes some of the differences in register illustrated by our invented courtroom discourse. Note how there are differences at every level, and that we assemble and interpret language in bundles of elements from each level. Together, these elements constitute registers from a shared social repertoire.

Table 2.3 Comparison of formal and informal registers

Diglossia is the (perhaps universal) use of (normally two) different languages, varieties or registers of differing levels of prestige for different situations and/or purposes. So, for example, in a Welsh bank the cashiers might use Welsh with their customers but English when requesting approval for leave from the area manager.

For bilingual or multilingual speakers, different languages may serve the same purpose as registers do for monolinguals (a phenomenon known as diglossia). See Chapter 8 (on bilingual and multilingual education).

2.3 Standardization and ‘Non-Standard’ Varieties

If some dialects become recognized as the ‘standard’ for their respective languages, how does this happen? As we pointed out in Chapter 1, the ability to recognize differences in the ways people speak is perhaps part of our biological endowment as ‘the linguistic species’. But how do we go from recognizing that people from the next town or village (or on the other side of the hill or river) speak differently, to widely shared perceptions of the relative value of the multiple varieties we come into contact with? To a neutral observer, the kind of visceral reaction to language variation we cited at the beginning of the chapter may appear surprising, given the linguistically arbitrary nature of the distinction between ‘standard’ and ‘non-standard’ varieties. A variety can become regarded as the standard through a series of events and conditions that favour its acceptance and spread, not because it is linguistically more complex, inherently more effective as a vehicle for communication, ‘purer’ or more logical than other varieties (all ‘dead ends’ we met in Chapter 1). It may be that as more people come into contact with the standard as a result of its use in literacy, school or the mass media (more on this on pp. 38–9) they will come to regard it as more accessible or easier to understand than other dialects of the same language, but that is a feature of circumstances of its use (who speaks it where) rather than an inherent property of its form.

An idiolect is the unique form of a language represented in an individual user’s mind and attested in their discourse.

Preston (2002, pp. 62–64) argues that the identification in most people’s minds between attitudes to speaker and attitudes to speech can only be fully explained if we acknowledge the fundamental opposition between linguistic and non-linguistic theories of language. His characterization of the ‘folk theory’ (Figure 2.3) echoes our ‘monolithic myth’, with ‘the language’ seen as an ideal object, abstracted from ‘good usage’ and distinct from ‘ordinary language [use]’, which is itself either ‘dialect’ or ‘wrong’. Whereas the folk theory defines ‘the language’ in terms of value, a linguistic theory (Figure 2.4) views ‘the language’ as a collection of dialects, which themselves are viewed as collections of overlapping but distinct realizations of cognitive systems in individual minds (known as idiolects in sociolinguistics). No value judgements are made, no dialect is privileged over any other. ‘The language’ is not the same thing as ‘the standard variety’, which is one dialect among others.

Figure 2.3 A folk theory of language (adapted from Preston, 2002, p. 64)

Figure 2.4 A linguistic theory of language (adapted from Preston, 2002, p. 64)

As we argued in Chapter 1, we believe that a linguistic view of language informed by psycho- and sociolinguistics makes a fundamental contribution to applied linguistics. By adopting this view, applied linguists can understand and contest the monolithic myth of the ‘standard’ version of languages, and all the prescriptivist baggage that comes with it. Without it, we are prone to fall victims to what Lippi-Green calls standard language ideology:

a bias toward an abstracted, idealized, homogenous spoken language which is imposed and maintained by dominant bloc institutions and which names as its model the written language, but which is drawn primarily from the spoken language of the upper middle class.

(Lippi-Green, 1997, p. 64)

Writing and Technology

It is often argued that written language serves as a sort of fixative, analogous to the chemical process of ‘fixing’ just the right shades of black and white on a photograph in a darkroom. Thus, in the case of English, the dialect ‘frozen’ by print was that spoken where the earliest English printers worked, in the power triangle between Oxford, Cambridge and London (but not the ‘Cockney’ variety of the capital spoken by Shaw’s Fair Lidy). The idea of ‘fixing’ through print is even more explicit in the policies and practices of the major European language academies, those official organizations which regulate how the national language is to be used in public domains. The stated purpose of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française (founded 1694), for example, is to ‘fix the usage of the language’ (Fixe l’usage de la langue). Similarly, the motto of the Real Academia Española, which published its first dictionary in 1780, is ‘Limpia, fija y da esplendor’ (cleanse, fix and make resplendent). Hence, physical fixing became social fixing, with print serving to maintain the status of one variety over others.

Glottographic writing systems use symbols which represent sounds, either individual phonemes (as in alphabetic codes like the one used for English) or syllables (as in the syllabary used for Inuktitut in Canada or the Japanese hiragana and katakana scripts).

Logographic writing systems use symbols which represent whole words or ideas. They normally encode no (or only limited) information about how the symbols are pronounced (compare the logographic symbol & with alphabetic and) and no (or only limited) iconic information about what the symbol means (so ☺ is not a logographic symbol, but is – it’s a word for ‘face’ in Chinese script).

It’s worth pointing out that systems which function by representing the sounds of a particular language, like alphabets and other forms of glottographic writing, lend themselves especially to this fixing process (see Chapter 6). In contrast, the spread of logographic writing systems that convey messages primarily via word-images, such as Chinese characters and the systems developed by Mesoamerican groups, can be read in different language varieties, without favouring one over others. This doesn’t mean that such systems were not highly stylized or that they didn’t promote certain (visual) conventions over others, but due to their nature their effect on establishing standard varieties of speech was likely very limited. The flip-side of this is that because they are largely meaning-based, rather than pronunciation-based, such systems can be used to claim unity around a standard where in fact there is diversity, even multilingual diversity. Such is the situation with written Chinese, called Zhÿngwén, literally ‘Writing of the Middle Kingdom’, but often used to refer to Standard Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua, or ‘common speech’, based on the Beijing dialect). Although non-linguists both inside and outside China think of the nation as having a single national language with many dialects (together with some minority languages like Uighur or Mongolian), linguists normally deny the existence of a single Chinese language, recognizing instead members of a Chinese language family, which includes Mandarin and Cantonese. The fact that Mandarin and Cantonese and all the other ‘dialects’ of Chinese can be written with the same logographic system licenses politically convenient assertions of a single Chinese language. A logographic system also similarly lends itself to use as a tool of cultural assimilation, e.g. in Hong Kong, where Cantonese is spoken. During the twentieth century, however, Cantonese developed its own written form, but it is not yet standard, despite its increasing use in chat rooms and SMS messaging.

In addition to writing, the spread of sound-based communications technologies such as radio and television has helped fix the sound of certain varieties as the ‘standard’ in the minds of listeners. But there is a perpetual tension between innovation and standardization, given changing social dynamics and increased contact between speakers of different languages and varieties. The central pull of the prestigious broadcast accent in the UK seems to be losing its power, for example. BBC news readers historically have been speakers of RP, but today’s listeners and viewers can hear a much broader range of regional accents. Furthermore, the rapid spread of digital and interactive technologies, such as smart-phones and personal computers, and broadening access to them, means that users are potentially receiving input in a much greater range of language varieties. They are also able to produce and send messages in their preferred varieties through the social networking, podcasts, blogs and chat functions of virtual, computer-based communication. But perhaps the key word here is potential, as given the greater number and range of broadcasting options and the increased ease of access to them, listeners are also able to choose to decrease the range of voices they are exposed to. Certainly the picture is a very complicated one; while technology can provide an outlet for frequently unheard language varieties, it also facilitates contact and standardization, as well as the fracturing of the audience into smaller and more specialized groups who can choose to avoid language varieties other than their own.

2.4 Non-Native Varieties and World Englishes

The spread of languages of wider communication, including Chinese, Arabic, English and Spanish, means that many of us live in ever richer speech communities in which multiple languages are present. This contact leads, in many cases, to speakers learning and using additional languages, that is, retaining their first language while gaining another or others (see Chapters 9 and 10). While theoretical and descriptive linguists have traditionally focused on people’s knowledge of their first language, interest in language use by non-native speakers is growing rapidly. This is particularly true for the growing numbers of non-native users of English, estimated at over one-third of the world’s population (Graddol, 2006; Crystal, 2008). Thus, applied linguists and language professionals working in education, translation and other areas face decisions about whether it is right or realistic to expect non-native speakers to attain native speaker ‘status’ – to perform, at least in certain contexts of use, like native speakers (see Chapter 9 on the notion of native-speakerism).

There are at least two ways of looking at this issue. From an individual perspective, applied linguists devise and interpret tests, tasks and other means of measuring language learners’ abilities in certain aspects of language use. The IELTS (International English Language Testing System) and the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) are good examples of tools which attempt to assess whether an individual has mastered the elements of English needed to perform successfully in an English-speaking university. Likewise, professional standards developed by the organization Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) are intended to gauge which teacher candidates have developed levels of proficiency that will allow them to be effective teachers of that language. Such measures are ways of operationalizing the minimal threshold of non-native speaker proficiency (in this case, of English) to satisfy the linguistic requirements of learning and teaching that language at scholarly and professional levels. All attempts to measure language proficiency face a number of problems, however, including what to test and how to test it in a way that is accurate and fair, a topic we return to in Chapter 9. The question of ‘what to test’ is relevant here, as the answer to this question will involve making a decision about the relevant variety of the language to be tested and a rejection of those varieties considered irrelevant to the target situation (see Davies et al., 2003).

Additional languages may be classified as second languages when they are routinely used in a country outside the context in which they are learned (for example in bilingual countries) and as

Non-native varieties can also be viewed collectively, as in the case of World Englishes, an approach to English which highlights the historic diversification that the language has undergone as a result of successive ‘diasporas’ (dispersions) of its speakers (see Kachru et al., 2006; Kirkpatrick, 2007). The term pluricentric is regularly employed in this paradigm, to suggest that English is a collection of national or regional varieties, both in the ‘Anglo’ countries of colonist England and colonized Scotland, USA, New Zealand, etc. and in the non-Anglo colonized nations of the Indian subcontinent, Africa, South-East Asia, etc. In the first, there are national standard varieties spoken by native speakers (Scottish English, Australian English, etc.). In the second, emerging non-native standard varieties of English (Indian English, Nigerian English, etc.) vie with other native languages, such as (predominantly) Hindi-Urdu in South Asia, or Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa in Nigeria. These ‘new Englishes’, also called indigenized or nativized Englishes (see Kachru, 1992, pt II), face a struggle for recognition both in the ‘Anglo’ countries and in the countries in which they arose, because as second languages, they are unquestioningly valued less.

The ‘norms’ of the native varieties are pretty much established, codified in dictionaries and descriptive grammars, and rendered as models in education and writing. So, for example, when mentioning the first and last items of a list, the norm for British English is to use the preposition to (vegetarian recipes: from apples to courgettes), whereas the norm for US English is to use the preposition through (apples through zucchinis). The ‘norms’ of the new varieties, however, are only beginning to be accorded similar status within their local domains, and codification itself is not yet prevalent. For example, ‘Standard Nigerian English’ lacks a dictionary, usage guide or pedagogical grammar, but does satisfy other indicators of its ‘standardized’ status. Bambgose’s measures of the status of innovations in nativized varieties (Bambgose, 1998) can help here (see Table 2.4). Some Nigerian English usages, such as I don’t mind to go, are used by most speakers, but are stigmatized by users of the prestige variety, and so are not, on Bambgose’s ‘demographic’ measure, part of Standard Nigerian English. Other usages, such as the homophony of beat and bit, cord and cod, and cart and cat, are common to almost all speakers, including teachers, and so are standard on his ‘authoritative’ measure. But they are not yet codified in pronouncing dictionaries, even though the contrast between the vowel sounds is still tested in Nigerian high schools, as Bambgose reported in 1998 (p. 8). (There is more on the role of dictionaries in codifying norms in Chapter 11, on lexicography.)

Table 2.4 Factors for determining the status of innovations in nativized Englishes (Source: adapted from Bambgose, 1998, pp. 3–5)

Factor |

Measure |

Demographic : How many people use the innovation? |

Number of users within the local variety with the most prestige. |

Geographical : How widely dispersed is the innovation? |

Usage across L1 backgrounds and geographical areas. |

Authoritative: Who uses the innovation? |

Usage in literature, education, media, publishing. |

Codification: Where is the usage sanctioned? |

Appearance in written form, especially in dictionaries and manuals. |

Acceptability: What is the attitude of users and non-users to it? |

Degree of awareness and favourable attitudes. |

foreign languages when they are not so used. English is learned extensively as a second as well as a foreign language, whereas Icelandic is always learned as foreign language, unless the learner is in Iceland.

When a language is used as a medium of communication between speakers of different languages, it is known as a lingua franca.

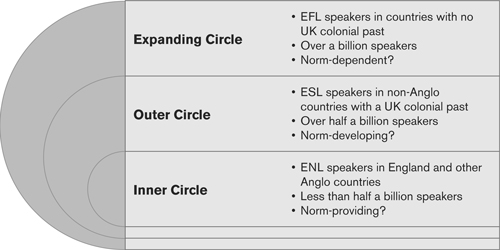

The Expanding Circle is Braj Kachru’s (1985) term for the regions where English is used mainly as a foreign language, and where most of its users may now be found.

The Outer Circle is his term for where English is used mainly as a second language, in former colonies of the UK and USA, where new norms may be developing.

English is used mainly as a native language in the Inner Circle: the British Isles and the regions where English native speakers effectively displaced local populations.

The multiple native and nativized Englishes can be contrasted with those developing in countries where the language has no official status and are first encountered in classrooms rather than in the institutions left by conquest and colonization by England or one of its ‘Anglo’ daughters. In such contexts English is truly a foreign language. In effect, given the English-learning boom of the past half-century (Graddol, 2006), this means all the other nations on Earth, but typified by Europe, where English is increasingly used as a lingua franca, and China, where the number of people learning English is larger than the total number of native speakers on the planet. In Kachru’s model of World Englishes, representing the three domains we’ve just discussed in concentric circles (see Figure 2.5), this last domain is called the Expanding Circle, but it’s fairly clear that he’s using expanding here to refer to individual learners and users, rather than nations, as in the Inner Circle of native English speakers or the Outer Circle of ESL speakers.

Figure 2.5 A model of World Englishes (Source: adapted from Kachru, 1985) (Note: ENL = English as a Native Language; ESL = English as a Second Language; EFL = English as a Foreign Language)

English was originally imposed on the ancestors of many current speakers around the world, often through military force. Unsurprisingly, there are therefore ambivalent attitudes towards English in these countries. Some view the language as a symbol of continuing subjugation to foreign powers through cultural (rather than military) imperialism or of a lack of national self-confidence, sometimes perpetuating an inferiority complex. For others it represents the loss of cultural diversity and ancestral culture. The writer Vikram Seth’s poem Diwali illustrates this ambivalence. In it, he describes English in India as a ‘Six-armed god / Key to a job, to power / Snobbery, the good life / This separateness, this fear’. After independence, the ‘conqueror’s tongue’, as Seth calls it, did not, of course, disappear, and the legacy continued to be both a blessing and a curse. One response to the problem was to eliminate it. For example, the newly independent government of Malaysia replaced English with a variety of Malay as the only official language (known as Bahasa Malaysia), to give voice to the Indigenous peoples of the new republic and to promote national unity. Malaysia was bucking the postcolonial trend, however, and English remains an official language for around fifty nation states (Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are the only others to have struck English off the list, although for all three nations English maintains a prominent role in national affairs).

But when we talk of ‘English’ here, what variety of English exactly do we mean? Clearly the millions of users of English in the Outer Circle don’t all use the same variety, the one promoted as the only valid version by the teachers and textbooks imported from the USA and the UK and promoted by the British Council and agencies of the US Department of State. Although the snobbery mentioned by Seth ensures that most users in the Outer Circle value the same dialects considered ‘correct’ by Inner Circle speakers, the reality on the ground is just the same as in the Inner Circle: users of English in the Outer Circle represent a rich collection of many different varieties, clustering together as usual on the basis of geographical or social factors, and also influences from local languages. So, for example, terms like cousin-sister (‘female cousin’),big father (‘father’s elder brother’) and co-brother (‘wife’s sister’s husband’) in the Englishes of Africa and Asia reflect regional kinship systems (Mesthrie and Bhatt, 2008, pp. 112–113). And the extensive plural use of mass nouns in Sri Lankan English (like equipments and advices) is undoubtedly due to the fact that their translation equivalents in Sinhala, the dominant national language, are inherently plural.

The feelings of separateness and fear that Vikram Seth associates with English in India begin to dissipate when, as always happens, users appropriate the colonial language for themselves. The consequence of this is that they effectively refit it for their own purposes, just as every child does as they acquire their native language from exposure to the situated speech around them. The applied linguist Henry Widdowson has articulated this reality most persuasively, claiming that

[y]ou are proficient in a language to the extent you possess it, make it your own, bend it to your will, assert yourself through it rather than simply submit to the dictates of its form…. So in a way, proficiency only comes with non-conformity.

(Widdowson, 1994, p. 384)

Just as infants forge changes in their ‘mother tongue’ by creatively reconstructing the system in each generation, and just as these changes fade or spread to the extent that they are generalized across the members of a speech community, so non-native speakers use the materials of the other language(s) they are exposed to to innovate, and these innovations too become distinctive features of non-native varieties, despite the power of the ‘standard language ideology’.

Pidgins and Creoles

Pidgins are very basic linguistic systems which sometimes emerge in situations in which speakers of different languages find themselves in frequent contact and need to communicate.

Creoles are complete languages that have evolved from more basic pidgin languages, in some cases in a matter of two or three generations.

In a language contact situation, the superstrate language is the one spoken by the politically and socioeconomically dominant group.

The substrate language is spoken by less powerful speakers, and influences the development of grammatical features in an emerging variety based on superstrate vocabulary.

The concept of national varieties and learner varieties still suggests that English is a self-contained collection of overlapping systems, independent of all the other languages being spoken by the same people or others around them. This rather oversimplifies the nature of actual language use around the globe, and so is not going to be sufficient for user-oriented applied linguists who wish to fully understand their clients’ problems. The untenable fiction of ‘separate’ languages is particularly well exposed by the existence of pidgins and creoles (see, for example, Holm, 2000). Pidgins tend to rely on a powerful (typically European) language, known as the superstrate, for their vocabulary, but use these words in grammatical frames influenced more by speakers’ (normally less prestigious) mother tongues, known as substrates. In Nigerian Pidgin, for example, the source of most words is English, but much of the syntax and morphology is supplied by Nigerian languages like Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba.

Once a pidgin is acquired as a native tongue by children it evolves into a creole. Creoles are full language systems, endowed over the course of a few generations with complete grammars and extensive vocabularies, through the rich psycholinguistic events unfolding in children’s minds as they participate in the social world around them. Pidgins and creoles typically arise in contexts such as the following:

trade, especially at ports and along shipping lanes;

trade, especially at ports and along shipping lanes;

slave plantations, especially in the Caribbean islands;

slave plantations, especially in the Caribbean islands;

multilingual states, as a result of colonial invasion or postcolonial union;

multilingual states, as a result of colonial invasion or postcolonial union;

sign language, through creative construction by children.

sign language, through creative construction by children.

The likelihood of creolization varies in each context. So, for example, it’s less likely in trade contexts, because these are utilitarian and temporary, and more likely where social cohesion is favoured by common cause, such as slave plantations or new nations. The emergence of creoles in sign language contexts will depend on the uniquely variable dimension of generational continuity: most (more than 90 per cent) of deaf children are born to speaking parents (Mitchell and Karchmer, 2004). But there are cases where creoles have arisen from interaction between pidgin signers, the best-documented of which is Nicaraguan Sign Language (Kegl and Iwata, 1989).

Decreolization occurs when a creole begins to merge with varieties of the superstrate language through (renewed) contact with it.

Something similar can happen in reverse with spoken creoles, in what linguists call the decreolization process (Holm, 2000, p. 49 ff.). Often, regular contact between creole speakers and monolingual speakers of the superstrate language increases over time. The superstrate language normally has greater prestige and is used in educational and other ‘official’ contexts, so with increased access to education and the media, and with creole speakers’ social aspirations finding linguistic expression through the acquisition of desirable superstrate features, the creole may gradually lose elements from the original substrate language and gradually come to resemble the superstrate. Since the superstrate is very commonly English, the decreolized variety often becomes a variety or dialect of English. Some linguists claim that this is the case of African American English and Hawaiian Creole. Figure 2.6 illustrates the pervasive nature of the pidginization–creolization process in the linguistic history and diversity of our world.

Figure 2.6 Examples of pidgins and creoles around the world

As in so many areas of the sociolinguistic reality of our planet, the monolithic myth has overwhelmingly negative power in the case of pidgins and creoles too. Creoles are seen as inherently ‘mongrel’ or ‘half-breed’, and so are consistently disparaged. Hawaiian Creole, for example, was vilified for much of the last century, as the following passage starkly describes:

One elementary teacher … claimed that children should be taught contrasting images to associate with Pidgin and good speech. ‘Words spoken correctly and pleasingly pronounced,’ she wrote, ‘are jewels, but grammatical errors and Pidgin are ugly.’ She urged teachers to tell children that Pidgin was like the ‘frogs, toads, and snakes‘ in the fairy tales they were reading. Good speech was like the roses, pearls, and diamonds that dropped from the lips of the good sister who helped people and was beautiful. As speech sounds came into fashion as a topic of scientific study in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s in American universities, there was a trend in Hawai’i toward identifying Pidgin as incorrect sounds and as evidence of speech defect. In 1939–40, newly trained speech specialists tested for speech defects in 21 schools. They found them in 675 of the 800 children they tested.

(Da Pigin Coup, 1999)

The monolithic myth is still strong, even in core areas of applied linguistics like language pathology, as we see in the next section.

2.5 Linguistic Insecurity and Language Loss

For an automatic communication device that operates mostly under the level of consciousness, it is actually quite startling to realize how language is also such a powerful component of people’s sense of themselves and the ways they relate to others. The discourses of prescriptivism, the monolithic myth, the standard/non-standard distinction and the inbuilt defectiveness of the non-native speaker all reflect the ways people believe language should be used by themselves and by others. It’s no surprise, then, that those socialized into a particular speech community share conventions for representing social hierarchies through language. The myth of a single ‘correct’ or proper form of speaking, and the fact that it is actually enforced through schooling, language academies and official language policies, contributes to a strong sense of what Labov termed linguistic insecurity in many speakers lower down the hierarchies (e.g. Labov, 1972, chs 4 and 5). One can think of numerous examples of cases in which individuals and groups act in the belief that their language variety is inadequate or that their own speech and writing are somehow inferior. Labov himself concentrated on New York City, just over the Hudson from where he was born. In a number of influential publications in the 1960s he showed how many lower-middle-class New Yorkers exhibited not only insecurity about the way they talked but even linguistic ‘self-hatred’.

A Google search in January 2010 for ‘accent reduction’ businesses in New York yielded over 600 hits, showing that this insecurity is still alive. Although most of these are aimed at the millions of ESL (English as a Second Language) learners and users in the city, many are designed also for native speakers. Some are qualified language pathologists, and although the USA’s leading professional body (ASHA, 2010) clearly states that ‘accents are NOT a speech or language disorder’, it does include accent reduction as one of the services offered by holders of its Certificate of Clinical Competence. The following excerpt from an online message board illustrates how strong the insecurity is, how it’s guided by a desire to conform to local conditions as much as to be ‘correct’, but how the association with speech defects prevails.

i was born in new york and have never left the cpuntry but i have a haitain accent for sum reason. anyway i need sum help reducing the accent and preferably changing it to a new york accent (though i really jus want to lose my accent … any tips, websites, or anything else would help

…

All I can say is good luck! I also have an accent and I’ve learned to just live with it. I can’t say some words like Sheet because it sounds like Sh*t. And when I say Beach it sounds like B*tch.

…

if you can afford it – go to a speech therapist – this is something tehy work on

Once more, here we are witnessing broad parallels between ‘standard’ vs ‘non-standard’ forms on the one hand and ‘native’ vs ‘non-native’ on the other. The notions of status, solidarity and power underlying ‘folk theories’ of language variation pervade applied linguistic issues, in both mono- and multilingual contexts. And it’s the hegemony (dominance) of native-speaking ‘standard’ code users which is at the heart of many problems applied linguists are called upon to address. In language policy and planning, for example (Chapter 5), the prevalence of ideologically induced linguistic insecurity at the language level (as opposed to accent or dialect level) is a major contributory factor in language loss. In a seminal study of Hungarian/ German bilingualism in Oberwort in the east of Austria in the 1970s, Susan Gal found that use of Hungarian was falling off quite rapidly, with younger women spearheading the shift. Of these women she noted:

When discussing life choices they especially dwell on the dirtyness and heaviness of peasant work. Rejection of the use of local Hungarian, the symbol of peasant status, can be seen as part of the rejection, by young women, of peasant status and life generally. They do not want to be peasants; they do not present themselves as peasants in speech.

(Gal, 1978, p. 13)

Language choice is being used here in the same way that many newly urbanized young peasants in Mexico, and no doubt other countries, will allow their fingernails to grow to indicate that they are not farm labourers.

Linguistic insecurity is thus a significant barrier to efforts to maintain or revitalize threatened languages and varieties. Unlike the women in Gal’s (1978) study, many people view language change negatively, an example of decline rather than the inevitable result of language use over time. This assumption underlies the concept of a ‘golden age’ of language use, a time when people really spoke or wrote the language well. Speakers of vital and endangered languages alike can hold such views, of course, but the effects can be especially damaging in the case of languages that are losing native speakers. Take, for example, the case of Mohave, a Native American language indigenous to north-western Arizona and western California, now spoken as a first language by perhaps fifty elderly people. Clearly, the only viable means of survival for Mohave and countless other endangered languages is for elders to begin speaking it with younger speakers. And yet, language revitalization efforts are often stymied by grumbling elders, bemoaning how younger speakers can’t speak correctly. This leads, unsurprisingly, to younger speakers preferring not to speak the language for which they are criticized.

Personal and group linguistic security can thus be undermined by a monolithic view of language and by prescriptivist attitudes to language variation and change. And yet the very notions of ‘standardization’ and codification that in part give rise to such attitudes can, paradoxically, be instrumental in language maintenance and the development of pride in localized language(s). Acceptance and codification go hand in hand, as we saw earlier with Bambgose’s (1998) measures of the status of innovations in Outer Circle Englishes. So fixing a standard version of a minority or endangered language in writing, and especially through dictionaries, can be a powerful booster to the status of the language. (We discuss this further in Chapter 5, on language policy and planning, Chapter 6, on literacy, and Chapter 11, on lexicography.) The importance of ensuring that linguistic insecurity does not inhibit the transmission of localized languages is emphasized in this extract from the Manifesto of the Foundation for Endangered Languages:

the success of humanity in colonizing the planet has been due to our ability to develop cultures suited for survival in a variety of environments. These cultures have everywhere been transmitted by languages, in oral traditions and latterly in written literatures. So when language transmission itself breaks down, especially before the advent of literacy in a culture, there is always a large loss of inherited knowledge.

(Foundation for Endangered Languages, 2009)

The Rosetta Project (n.d.) is one of a number of initiatives which aim to document the planet’s linguistic diversity before its inevitable and drastic reduction over the next few generations (as much as a 90 per cent reduction by 2100 according to linguists’ estimates, e.g. Krauss, 1992). The Rosetta Project is assembling a publicly accessible digital library of over 2,500 languages, and has produced a disk (Figure 2.7) on which 13,000 pages of documentation for over 1,500 languages have been microetched at a magnification of 1,000 times.

Figure 2.7 Image of the Rosetta Project disk (Source: www.rosettaproject.org/)

But one may argue that ‘diversity fixed’ like this is more a linguistic than an applied linguistic project. Essential as this record of languages is, essential also is the acceptance of variation in language as an inevitable, and fundamentally dynamic, process. Applied linguists, both those who work at the level of language policy and planning and those who work with individual users, face the challenge of trying to balance the needs and desires of the individual language user, who may have aspirations which don’t coincide with those of local activists or well-meaning outsiders (like us). When linguistic insecurity and language loss are at stake, careful thinking about how best to achieve this balancing act is an essential, but subtle, challenge for applied linguists.

2.6 Context and Language Practices

Convergence in talk is when a person changes the way they speak in order to sound more like the person they are talking to (or more like the way they think the other person speaks). For example, an additional language teacher may use less complex syntax when she is talking to a group of beginning learners.

Divergence occurs when a person changes the way they speak to sound less like the person they are talking to, like the local who exaggerates his accent in order to differentiate himself from the incomer.

Language variation happens or is made to happen in particular contexts and practices, a passive result of circumstances or an active result of purposes, at the level of both individuals and groups. In other words, we speak differently to different people, at different times and places, during different types of activities, to achieve different outcomes. One way to think about this is to see all speakers as dialect shifters, switching varieties and registers to suit the communicative and social demands of the situations they find themselves in. The ability to modify your style of speaking as a way of attending to your interlocutor’s presumed interpretative competence, conversational needs and role/status is called ‘accommodation’. The study of accommodation focuses on convergence and divergence in talk; for example the tendency for locals working in the tourist industry to adjust their talk when speaking to foreign visitors (Giles et al., 1991). There are complexities involved in making these adjustments, as full convergence by one speaker can also be negatively evaluated by the person being spoken to, as an identity-threatening act (‘I can see that you’re not one of us, so why are you pretending?’). Switching of languages, varieties and registers actually unfolds within talk in very complex ways: the extent and frequency of convergence or divergence can vary within a conversation; speakers may express a desire to converge/diverge but not have the linguistic competence to achieve their aims; or specific task-based motivations may override the need for social approval/distance. In addition, a speaker’s assessment of another person’s speech is inevitably subjective, and involves all the judgements about interpretative competence, conversational needs and role/status that we have been talking about in this chapter.

Those of us for whom contact with other varieties is fairly limited are unlikely to have the same need to cross variety boundaries. In other words, our actual repertoire of language varieties is limited by experience. Those who live in multilingual communities or who have travelled to new speech communities for work, study and other purposes will have had some practice in monitoring other people’s language variety, and are likely to have developed at least receptive competence in the varieties to which they are exposed. The following dialogue from the movie Airplane illustrates this to comic effect. In it, the jive speech of two African American passengers is translated into Standard American English (SAE) for the flight attendant by an interpreter (earlier in the film their dialogue has subtitles). The interpreter is berated by one of the jivemen for assuming that he can’t understand SAE (‘I dug her rap’).

Mnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnn, hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm. | |

Attendant: |

Can I get you something? |

Jiveman 1: |

S’mo fo butter layin’ to the bone. Jackin’ me up. Tightly. |

Attendant: |

I’m sorry I don’t understand. |

Jiveman 2: |

Cutty say he cant hang. |

Woman: |

Oh stewardess, I speak jive. |

Attendant: |

Ohhhh, good. |

Woman: |

He said that he’s in great pain and he wants to know if you can help him. |

Attendant: |

Would you tell him to just relax and I’ll be back as soon as I can with some medicine. |

Woman: |

Jus’ hang loose blooood. She goonna catch up on the rebound a de medcide. |

Jiveman 1: |

What it is big mamma, my mamma didn’t raise no dummy, I dug her rap. |

Woman: |

Cut me som’ slac’ jak! Chump don wan no help, chump don git no help. Jive ass dude don got no brains anyhow. |

Exposure to multiple languages and varieties of a language may mean that convergence on other peoples’ ways of speaking is more likely but it doesn’t, on its own, ensure that convergence is always received as appropriate (‘[M]y mamma didn’t raise no dummy’) or associated with a positive assessment of the speaker (‘Jive ass dude don got no brains anyhow’). The implication here for applied linguists is that raising awareness of language variation, not just protecting or facilitating switching between varieties, is key.

2.7 Casting Ahead

Understanding that language difference is not equivalent to language deficit is a mainspring of applied linguistics, with relevance to all areas of professional practice. So we come back to the topic of (attitudes to) language varieties again and again in the chapters which follow, especially Chapter 7, on the language of education, and in our final chapter, Chapter 14, on future directions. Applied linguists understand that when a speaker of another variety ‘sounds’ different to us when she signs, speaks or writes, this is – as often as not – a result of our unfamiliarity with her variety of language and our suspicion of her as part of the unknown ‘other’. The responsibility of the applied linguist is to protect varieties and languages, as well as to raise awareness of the inevitability and usefulness of variety. In the climate of prescriptivism which we’ve grown to assume is normal, with its petty but popular fetish of language ‘standards’ and unquestioning belief in languages as monoliths, this responsibility is likely to prove a heavy burden.

Further Reading

Adger, C. T., Wolfram, W. and Christian, D. (2007). Dialects in schools and communities, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Chambers, J. K., Trudgill, P. and Schilling-Estes, N. (eds) (2002). The handbook of language variation and change. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kirkpatrick, A. (ed.) (2010). The Routledge handbook of World Englishes. London: Routledge.

Makoni, S. and Pennycook, A. (eds) (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Wardhaugh, R. (2006). An introduction to sociolinguistics, 5th edn. Oxford: Blackwell.