Chapter 13

Someone’s cut the string between each word and its matching thing.

(Gwyneth Lewis, Aphasia)

In the other chapters of Part C we have mapped specialized areas of applied linguistics which focus on potential problems related to the social manifestations of language – as an obstacle to be negotiated in Chapter 10, as a community resource in Chapter 11and as a medium for group standards of behaviour in Chapter 12. We end our guide to the themes and practices of applied linguistics by returning to the language code itself, its cognitive form. For unlike many areas of contemporary applied linguistics which can adopt a largely or uniquely sociolinguistic orientation, language pathology must grapple with the ultimate physical forms of language: the neural circuits which underlie grammar and lexicon, and the motor and perceptual systems which allow us to externalize and internalize the messages which grammar and lexicon jointly encode.

In focusing on the biological reality of language here, we must not – cannot – lose sight of its fundamental social and communicative purpose. Language pathologists, in common with all applied linguists, must always remain aware that they are dealing with broader human issues: that the disorders they diagnose and treat affect the very core of their clients’ lives as social beings. As we have seen with all the other areas of applied linguistics mapped in this book, language pathology is therefore inherently multidisciplinary. It employs the research findings, practical experience and expertise not only of linguists, but also of cognitive, developmental and social psychology, education and the health sciences.

There is a profusion of names associated with this area of applied linguistics. The specific application of linguistics to problems of language disability has been called ‘clinical linguistics’ by David Crystal (1981), whereas the broader term ‘language pathology’ is generally used to cover the whole professional/scientific enterprise relating to language-related disorders, from neurolinguistic theory to therapeutic practice. Practitioners whose main work is in clinics, schools, hospitals and patients’ homes, rather than in research laboratories, call themselves ‘speech and language therapists’ in the UK and ‘speech and language pathologists’ in the USA (see Crystal and Varley, 1998, p. 1, for names used in other countries). We opt for language pathology as a cover term here.

The chapter is organized as follows. First, in section 13.1, we’ll stress once again the dual nature of human language, as both an individual, cognitive system rooted in human biology and a shared resource embedded in, and articulating, sociocultural beliefs and practices. Then, after a brief tour of the biological landscape of human language, we describe some of the major types of language disability (13.2) and other disorders that can affect language use (13.3). This essential background knowledge will allow us to proceed to an account of the clinical and community-based practice of language pathologists at both the assessment (13.4) and treatment stages (13.5). As usual, a brief roll call of other roles for applied linguists closes the chapter in 13.6.

13.1 Biological and Social Foundations of Language

We have seen in previous chapters that language without social meaning is as unnatural as fish without water. Language evolved in the human species as a tool to share meaning in society. By sharing meaning through language, we were able to become progressively more social, ultimately cultural. Our creation of cultural groups and identities, with their own characteristic practices and beliefs, was accompanied by a remarkable growth in brain power: we became prodigious thinkers, and sharing meaning through language gave us progressively more to think about. A key component in the emergence of this unique way of being was the mystery of human consciousness: the awareness we have of ourselves and of the world around us. Luckily, this consciousness is limited to the important stuff. Much of the boring legwork of life is not available to our conscious minds, including most of language. This is what Hall (2005) has called being under ‘the Language Spell’, a metaphor we have exploited throughout this book.

But the blithe state of efficient ignorance that the Language Spell bestows on us becomes compromised once the subconscious mental apparatus that supports our language capacity breaks down or our children are born with apparatus which is faulty. If we are to help people solve problems arising from these situations, we must come to grips with the internal structure and functioning of language in the brain and the physical channels it uses to mediate understanding in the external world – as speech, sign, Braille and writing. Given this, we need to take a brief tour of language as it resides in, and is enacted by, the human body.

Even though almost all people use the vocal channel to communicate linguistically, and despite the use of terms like tongue and speech to refer to language, the central location of our linguistic capacity is clearly the brain, rather than the speech or hearing organs. Because we possess no telepathic power to share meaning directly with each other, we have to rely on an external channel, like speech, to do the job of message delivery. But speech doesn’t have a monopoly on this sociophysiological function: for sign languages, the same range of linguistic messages find outlet essentially through the hands. So we know that the vocal tract is not a necessary component of human language, but that language without brain is impossible. Furthermore, we know that language resides in the brain because we can measure the electrochemical activity generated there when people speak and listen or produce and comprehend sign languages (see Ingram, 2007, for a comprehensive overview of the research), and we can see the effects on language when the brain is damaged.

Neurological Underpinnings of the Language Faculty

Over the past century and a half we have come to understand a good deal about how language is represented in the neural tissue which constitutes the brain’s grey matter (the cerebral cortex). It’s too complicated to be located all in one particular region of the brain, like the blood-pumping function is located in the valves of the heart. In fact, language knowledge and activity are distributed throughout the neural tissue of the cortex. But certain regions around the Sylvian Fissure (the deep crevice running roughly from temple to ear) on the left side of the brain appear to be especially important for language processing (see Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas on either side of the Sylvian Fissure in the left cerebral hemisphere (side view, facing left) (Source: US National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders)

The cerebral cortex is the ‘grey matter’, the 2–4 mm layer of neural tissue covering the two cerebral hemispheres of the human brain, containing the neural networks responsible for ‘higher cognitive functions’ like language and visual processing.

A few people (especially left-handers) may have language function concentrated in the right cerebral hemisphere, or across both, but this is rare. Damage to Broca’s area on one side of the Sylvian Fissure or to Wernicke’s area on the other side will more often than not affect aspects of language production or comprehension, respectively. And yet the kinds of impairment resulting from damage to one of these areas can vary greatly, and damage to other areas can produce similar effects.

The cerebral hemispheres are the two halves of the cerebrum, the principal component of the human brain. You can take a 3D tour of the brain at the US Public Broadcasting System’s website for its series The Secret Life of the Brain . Eric Chudler’s Neuroscience for Kids site at the University of Washington has a page on language and the brain, and is also available in several languages, including Chinese and Spanish.

Broca’s area is a region of cerebral cortex associated with language production, located above the Sylvian Fissure, the deep crevice in each cerebral hemisphere running backwards from above the ear. Wernicke’s area is a region of cerebral cortex below the inner end of the Sylvian Fissure, which plays a major role in language comprehension.

So on the one hand, language appears to be localized to some extent, but on the other hand it also appears to be widely distributed throughout the brain. This apparently contradictory architecture makes sense, though, if you think about how it effectively minimizes the effects of brain damage. Not having all your linguistic eggs in one basket means that a lesion (injury) to an area of the brain lying outside the region of the Sylvian Fissure is less likely to result in a language deficit. And distributed representation means that if a language area is damaged, not all language functions and knowledge will be knocked out, and other areas may be able to compensate.

Language in other Parts of the Brain and the Body

Apart from the linguistic areas of the brain, damage to other areas of neural tissue can compromise language functions. We’ve argued that the essential function of language is to express meaning in a format that can be externalized as physical energy, with social objectives. So at least four other brain functions will be involved in successful language use: conceptual and social processes at one end, and perceptual and motor control processes at the other. We know very little about the neural correlates of conceptual knowledge (meaning) or of sociocultural beliefs and actions, but cognitive neuroscience has revealed a lot in recent decades about the sensory and muscular systems which allow us to produce and receive linguistic signals (Gazzaniga, 2009). We know, for example, that visual input from sign and writing is processed in the occipital lobes at the very back of the brain, and that acoustic input from speech is initially dealt with close to Wernicke’s area. For production, we know that the relevant motor routines required to engage the speech articulators in the vocal tract, together with the sign and writing articulators in the upper limbs, are controlled and coordinated by the ‘motor strip’ along the Fissure of Rolando, stretching roughly from the region behind the ear to the top of the head.

Furthermore, over a century of sustained scientific enquiry into the organic-muscular systems of the language modalities has revealed a lot of knowledge about the vocal tract and the speech processing system, although relatively less about reading and writing, and only a meagre amount about sign articulation and perception. Studies in articulatory phonetics have shown how language is externalized through the expulsion of air from the lungs through the continually morphing resonating chamber of the vocal tract, between the larynx (Adam’s apple) and the lips, nostrils, palate and teeth. Work in acoustic phonetics has taught us how the linguistically structured sounds produced by the contortions of the vocal tract are reconstructed on the basis of salient cues in the input. For example, sudden changes in amplitude and relative frequency help us identify sibilants, like the [s] or [z] sounds which produce energy at the highest levels of pitch, and distinguish vowels, like low [u] and high [i].

It’s an unfortunate truth that in our precarious existence any of the complex biological subsystems from which we are built may be compromised by malfunctions and accidents which occur as we develop as embryos, enter the world as independent organisms, mature into adulthood, interact with our physical and social environments, and decline in old age. The myriad components associated with language use are no exception. Actually, it’s a wonder that so many of us manage to survive with language intact for so long! One of the responsibilities of applied linguistics is to contribute expertise to aid those who are not as lucky in this regard.

13.2 Types of Language Pathology

Given that a defining characteristic of applied linguistics is its practical engagement with the language-related problems faced by individuals and groups, we need to address here the nature of the problems with which language pathology is concerned. But it’s not our purpose to describe language disorders comprehensively or in any great detail here. Following the rationale we set out in Chapter 1, we focus here on the practice of language pathology, rather than the theory and description of the disorders themselves – just as we focused on language teaching in Chapter 9, and left a summary of second language acquisition processes to other authors. But we do in this section map some of the descriptive territory, so as to be able to follow a number of principal routes in professional practice.

A simple way to start would be to claim that client issues in this area are ‘communication problems’. But this would admit too broad a range of phenomena, from miscommunication between groups because they don’t share a common language or dialect, through temporary breakdowns in communication because of a slip of the tongue or a noisy environment, to misinterpretations of gestures, facial expressions or other non-linguistic communication channels. A more limiting focus, then, so we can distinguish language pathologists from translators and other applied linguists, is reflected in the term ‘individual language-related disabilities’. One of the major issues for clinicians in the field is to recognize the vastly heterogeneous nature of such disabilities. Our knowledge of language and the brain is still very limited, but data from people with language-related disorders reveal an enormous variety of conditions, affecting one or more of the diverse processing mechanisms and knowledge structures that underlie the functioning of the language faculty.

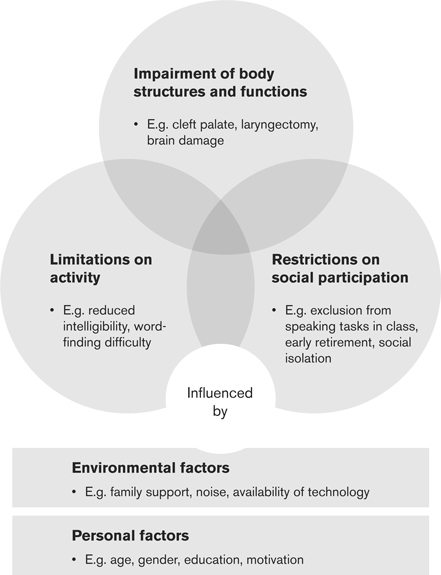

One of the central tenets of language pathology is that each client must be viewed individually and therefore diagnosed and treated according to their own unique psycho- and sociolinguistic profile, and their own communicative and social needs. The perspective of the client and their needs is central to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning and Communication Disorders (ICF) (WHO, 2001). Their scheme, summarized in Figure 13.2, ‘takes into account the social aspects of disability and does not see disability only as a ‘medical’ or ‘biological’ dysfunction’.

Figure 13.2 The International Classification of Functioning and Communication Disorders (ICF) (adapted from Ferguson and Armstrong, 2009, p. 29)

For our expository purposes here, we need to focus first on the disabilities, so that later we can pan out to appreciate the broader view. One way to form an impression of the scope of individual language disabilities is to identify them in terms of a series of central dichotomies in the dimensions of linguistic knowledge and/or linguistic processing affected. Some of these dimensions, with some examples of disabilities, are summarized in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Some central dichotomies used to categorize dimensions of individual language-related disability

| Dichotomy | Example |

System vs modality |

Aphasia results in damage to, or loss of, the neurally encoded language system, independent of modality; deafness leaves the system intact but affects one of the modalities of language use |

Reception vs production |

Wernicke’s aphasia can impair the reception of linguistic messages; Broca’s aphasia has greater impact on language production |

Congenital vs acquired |

Developmental dyslexia is congenital (either inherited or developing in the foetus); acquired dyslexia is normally the result of injury to the left hemisphere |

| Neurological vs non-neurological | Dysarthria impairs neurological control of the speech articulators (muscles used in speaking); cleft lip and palate affects the articulators themselves |

Before looking at three of these dichotomies in greater depth, let us just clarify once again that ‘dimension of disability’ doesn’t define individual clients: as we noted in Chapter 3, people with language disabilities, like all clients of applied linguistics, seldom – if ever – fall into neat typological categories.

System vs Modality

As we’ve repeatedly seen, language as a system of grammar and lexicon relies on speech and other external channels to get in and out of people’s minds. If the modality of delivery is damaged, language can become unusable to a greater or lesser extent, even if the internal system itself is completely spared. Consider deafness. If you have trouble hearing sounds, you will inevitably have trouble with hearing speech. Speech, though, is not language, but rather ‘language spoken’, which must be heard in order to be understood. Being deaf does not mean that you have anything wrong with your language capacity: your linguistic system will develop and be used as normal if you also use another language modality which does not depend on speech, such as sign. An example of damage to the system, on the other hand, is aphasia, the range of disorders resulting from damage to areas of the brain responsible for specifically linguistic functions. Aphasias are caused by prolonged interruption to the flow of oxygen to the brain through the blood supply (often through strokes or haemorrhage) or destruction of neural tissue (through disease or injury, for example). You will not have aphasia if the damage or disease bypasses the language areas completely and affects only the areas of the brain responsible for auditory processing.

Aphasia is an impairment or loss of linguistic knowledge or ability. It may be due to congenital or acquired brain damage. It is sometimes called dysphasia when language loss is not total.

But the two concepts cannot be separated completely. If a child is born deaf and the parents and/or other care-givers use only spoken languages as opposed to sign languages, then the child will not acquire a fully fledged linguistic system, since for this to happen linguistic input is required from the environment to trigger the system’s growth. Also, damage to the system may be intimately related to issues of modality too. It’s no coincidence, for example, that aphasias which affect the processing of grammatical structure in incoming speech involve damage to areas of the brain which are also associated with auditory processing in general. It is possible, too, that some aphasic individuals may be able to use language almost normally in the written modality but not the spoken, or vice versa (Crystal and Varley, 1998, pp. 170–171).

Developmental vs Acquired Disabilities

Children may, in effect, be born with a language disorder, either due to a traumatic event or disease occurring during gestation/birth, or possibly because of some inherited trait or condition (see the sub-section on specific vs general on pp. 307–8). Alternatively, the disorder may have been caused by the environment, any time from infancy to old age. A major difference between the two is that developmental disorders affect the acquisition of linguistic knowledge and processes, whereas acquired disorders affect the knowledge and processes previously acquired. This will clearly have important consequences for treatment, since the child with a developmental disorder will need a therapist’s help to learn, whereas an adult or older child with an acquired disorder will require assistance to recover what they have already acquired. Although aphasia, for example, is normally defined as an acquired state and is most often associated with older adults who have had a stroke, early damage to the brain’s language centres can affect the development of the emerging language system or the ways we process it.

One language-related impairment that comes in both developmental and acquired versions is dyslexia, affecting reading and writing (among other non-linguistic processes). This complex range of conditions, experienced by significant numbers of people in some literate societies, is not yet fully understood by psycho-or neurolinguists. There’s broad consensus, though, that at the root of many of the dyslexic syndromes is a problem with the use of phonology in the encoding and decoding of writing (although science moves fast, and other possibilities are currently being investigated – see, for example, the research review authored by Rice with Brooks (2004, pp. 42–70)). A dysfunction in the ‘metalinguistic’ ability to focus conscious attention on naturally acquired phonology is not going to affect speech itself, cocooned as it is by the Language Spell. But it will show up in the socially learned ‘re-representation’ of spoken language required by glottographic (sound-based) writing systems. This is especially so when the relationship between the elements of the writing system and the elements of the phonological system is supposedly one-to-one but is not exclusively so. For example, fewer cases of dyslexia surface in Spanish speakers than in English speakers. This is presumably because the spelling conventions of Spanish represent in a more or less direct way the phonemic sequences that make up spoken word form, whereas in the latter spelling is sometimes rather arbitrary. In Spanish you can confidently pronounce almost any newly encountered written word, but in English how would you know how to pronounce the newly coined word zough? (Think of the o u g h sequence in dough, thought, rough and plough.)

Some kinds of dyslexia may be present at birth, through either genetic inheritance or processes of hormonal development at the early foetal stage. Other kinds of dyslexia may be acquired in adulthood, through injury to the left cerebral hemisphere (often resulting also in Broca-type aphasia). The development of literacy skills is an extremely variable process, influenced by socioeconomic and other factors (see Chapter 6) rather than running according to a biologically predetermined sequence. The disruption caused by developmental dyslexia is therefore particularly acute, since other neural circuits will not automatically compensate, as they do in the case of disruptions to the early development of innately based abilities. Early detection and treatment will therefore be critical. With acquired dyslexia, however, the problem is slightly different: it is likely that the patient will have already learned how to read and write, and additionally will have assumed the social abilities and attitudes which come with literacy. If the brain damage they suffer leaves other cognitive skills intact, their loss will hit them extremely hard, and a range of different kinds of therapies will be called for. See section 13.5 for more on treatment.

Specific vs General

A disorder may affect linguistic and non-linguistic capacities and skills, or language alone. The set of conditions called apraxias are specific to language modality, for example, leaving related motor functions unimpaired, whereas dysarthria will affect all activities carried out by the muscles controlled by the damaged areas of the nervous system. One set of language-specific disabilities that have provoked a lot of scientific interest (and considerable controversy) in recent years are those named collectively Specific Language Impairment (SLI), thought by some researchers to be caused by genetic factors involved in the emergence of grammar during language acquisition (Fisher and Marcus, 2006). One family of English speakers (reported in Gopnik et al., 1997), exhibits three generations of individuals with grammatical rule disorders, from the grandmother down to twelve of her grandchildren (see Figure 13.3). The language-impaired members of the family reportedly have hearing and general cognition in the normal range, and although some have problems with speech articulation, tests appear to show that these problems are not the cause of the grammatical problems.

Figure 13.3 Family tree for three generations of a family affected by SLI (Source: reproduced with permission from Gopnik et al., 1997)

Apraxia is a motor planning disorder involving impairment or loss of the ability to make voluntary movements, such as the articulatory gestures involved in speech. Dysarthria is a speech articulation disorder caused by damage to the nerves that control muscles in the vocal tract and lungs.

In Down Syndrome, language acquisition and linguistic communication will also routinely be disrupted as the result of genetic mutation, in this case a mutation that involves an unexpected extra copy of certain information in the chromosomes. But the syndrome never affects language alone. It often has very wide-ranging effects across the whole spectrum of human attributes, from physical appearance to cognitive performance. A therapeutic programme for a child with Down Syndrome, then, may contain some of the treatments called for in SLI, but will go way beyond this, and language will be only one component in a complex set of communicative, psychiatric, social, health-related, educational and physiological concerns. It is not yet clear if the language problems of people with Down Syndrome are due to actual changes in the way language acquisition unfolds or merely to delayed language acquisition associated with non-linguistic aspects of the condition.

Non-Linguistic Disorders Which Affect Language

Some disorders involve damage to neither the language components of the brain nor the perceptual and expressive pathways of language modality. In our definition of language as a cognitive mechanism which evolved to transform sound into social meaning and social meaning into sound, we’ve stressed that it’s the social meaning part of the equation which is all-important. Consequently, a pathological condition which limits a person’s ability to make sense of the physical and social world in which they live and/or to conceptualize messages about themselves and their world may well be associated with language problems too. For theorists of language, one of the most interesting facts in this domain is that some general cognitive disorders of this kind do affect language, whereas others don’t. This kind of ‘double dissociation’ has been argued to constitute further evidence for the cognitive modularity of the language faculty mentioned earlier: the idea that language, at some level, is a separate system from the rest of cognition.

A relevant (and very ironic) example of double dissociation is presented in the set of ‘clinical tales’ published in 1998 by the British (but US-based) neurologist Oliver Sacks, under the title The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat. In a chapter called ‘The President’s Speech’, Sacks describes the reactions of some of his patients to a televised speech by the US president. The aphasic patients, with damage to their language comprehension systems, do not take the president seriously, laughing at him for his insincerity. But how can they apprehend his mental state if not through what he says? Sacks explains that they develop an enhanced sensitivity to

vocal nuance, the tone, the rhythm, the cadences, the music, the subtlest modulations, inflections, intonations, which can give – or remove – verisimilitude to or from a man’s voice. In this, then, lies their power of understanding – understanding, without words, what is authentic or inauthentic. Thus it was the grimaces, the histrionisms, the false gestures and, above all, the false tones and cadences of the voice, which rang false for these wordless but immensely sensitive patients.

(Sacks, 1998, p. 82)

Sacks compares their reactions with that of another patient, Emily D., who has tonal agnosia: she is unable to recognize the expressive qualities of voice, but processes the words in their grammatical sequences perfectly normally. She is a negative image of the aphasic patients, hence the double dissociation. Here is Sacks’ description of her reaction to the president’s speech:

People with one of the many kinds of agnosia are unable to recognize selective aspects of what they perceive. So, for example, someone with visual agnosia might see a familiar object but not be able to make sense of what it is (like Sacks’ real patient ‘who mistook his wife for a hat’). Someone with verbal agnosia might hear words spoken to them but not know which words they are, even though they can read, write and speak them.

It did not move her – no speech now moved her – and all that was evocative, genuine or false completely passed her by. Deprived of emotional reaction, was she then (like the rest of us) transported or taken in? By no means. ‘He is not cogent,’ she said. ‘He does not speak good prose. His word-use is improper. Either he is brain-damaged, or he has something to conceal.’ Thus the President’s speech did not work for Emily D. either, due to her enhanced sense of formal language use, propriety as prose, any more than it worked for our aphasics, with their word-deafness but enhanced sense of tone.

(Sacks, 1998, p. 84)

In case you’re wondering, Sacks does not mention the president’s name … but the piece was written in 1984 (not 1998).

13.3 Assessment

We now turn from theory to practice, from decontextualized brains to contextualized whole people. Imagine that a fifty-eight-year-old man, let’s call him Joban, arrives home from work one day in distress and unable to communicate with his wife. She takes him to the doctor, who refers him to a speech and language therapist. How does the therapist find out what’s wrong? She will probably start by making an initial assessment on the basis of information gleaned from Joban’s medical history, an interview with his wife and observation of, and interaction with, Joban himself. But the therapist will know that a much deeper investigation is needed in order to propose an effective treatment programme. Because language is many things at many levels – simultaneously biological, psychological, social, cultural and personal – she cannot restrict herself to the traditional diagnostic practices of the medical profession, which normally seek first to identify the organic causes of the pathology. Joban’s language problem may not have an evident physiological cause at all, and so treatments aimed at removing it would be pointless. The medical approach to assessment may well turn out to be more promising than other lines of investigation, of course: it’s possible that Joban’s condition could turn out to be due to an accident damaging his hearing and causing severe psychological trauma.

The therapist will be part of a team of professionals, each with a different area of expertise, and they must cast the diagnostic net more broadly than the physician, employing an ample battery of assessment tools drawn from medicine, linguistics, cognitive psychology, neuropsychology and social psychology. Let’s say that a neurological analysis reveals blood clots in the perisylvian region of Joban’s brain, providing evidence that his problem is indeed specifically linguistic: an aphasia caused by a stroke. It’s tempting to suppose that an experienced therapist could assess the nature and extent of the damage simply by talking to him informally and analysing his answers. This option would clearly be the least stressful for Joban. But to be clear about the extent and nature of the linguistic problem, she might instead need to carry out a series of specialized tests, adapted from experimental methods used in psycholinguistics, designed on the basis of technical knowledge from descriptive and theoretical linguistics, and complemented by pragmatics research and conversation analysis. We now turn to a description of such measures.

Tests and Samples

In section 13.2 we mentioned some of the multiple dimensions on which language-related disorders may vary. This is due in part to the way language is compartmentalized in the mind, in a series of modules dedicated to processing different kinds of linguistic information (phonological, morphological, syntactic, etc.). A very structured kind of linguistic assessment, informed by cognitive neuropsychology (e.g. Whitworth et al., 2005), is therefore often necessary in order to pinpoint the underlying modular disruptions involved in any given surface deficit. Tasks using a range of words, controlled for frequency, grammatical features, concreteness of meaning, etc., can be very powerful, from picture-naming used to test the extent of anomia, to nonword repetition used to assess phonological short-term memory. In the UK, the most well-known battery of such tests is found in the Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA; Kay et al., 1992), which contains sixty assessment tools targeting different combinations of modality, processing direction, grammatical level or function, etc. (Ferguson and Armstrong, 2009, ch. 10, provide a comprehensive list of other standardized tests, including the Western Aphasia Battery, used more widely in the USA.)

Anomia is a type of aphasia in which word-finding is impaired. People with anomia might recognize objects but be unable to name them.

Nonwords are potential word forms of a language (like splord or flobage in English), normally devised by psycho- and neurolinguists for use in lexical processing experiments and the assessment of language-related disabilities which affect the use of words.

Here is an example of an assessment (number 38) from PALPA. It requires patients to supply a definition for regularly and irregularly spelled homophones in order to assess any impairment in access to word meaning from written input (Whitworth et al., 2005, p. 72). If the patient typically confuses homophones like bury and berry (defining the first as ‘something that grows on bushes’ and the second as ‘to put in the ground’), then the therapist can surmise that a common phonological route (via /bεri/) is being used to access mental concepts and that the spelling disambiguation is not being exploited. If they confuse the regularly spelled berry but respond to irregularly spelled bury with ‘that’s not a word – /bjυəri/’, then the therapist can conclude that access to meaning is only available through letter-to-phoneme spell-out, the same way you would react to a nonword like gury or mury. Examples of similar tests can be seen (and even test-driven!) on the internet as part of the multimedia textbook on neuropsychology developed by Inglis, Newsome, Tang and Martin (2002) from Rice University in Texas.

Stackhouse and Wells (1997, 2001) have developed a profiling scheme based on these psycholinguistic processing models to be used to assess children’s difficulties with speech and spelling. The profile (Figure 13.4) is based on the broadly held position addressed earlier, that early alphabetic literacy development is dependent on phonological awareness: the child’s ability to reflect on, recognize and manipulate phonological units such as phonemes and syllables (see Chapter 6). The pathways in the diagram characterize successive stages in the processes of speech reception (A–F) and production (G–K), with stages at the top more dependent on stored linguistic knowledge than stages lower down. Stage L represents the child’s ability to self-monitor (i.e. to attend to their own output as input). Various data elicitation tasks are associated with each stage. For example, at Stage B the child should be able to tell whether two made-up words (nonwords) are the same or different; Stage F can be tested by asking the child to decide whether pairs of words rhyme or not; for Stage H the child might be asked to pronounce a word with the first consonant missing (‘Can you say “spot” without the “s”?’).

Figure 13.4 Speech Processing Profile (adapted from Stackhouse and Wells, 1997)

As useful as such carefully elicited quantitative data can be, though, they can’t be used in isolation. Some of the tests have much in common with the evaluation instruments we talked about in Chapters 7 and 9, used to assess a learner’s competence via discrete-point questions. One of the major shortcomings of such tests when used alone is that they are often decontextualized, completely unconnected with meaningful, motivated, socially embedded communicative acts (in which language itself is not part of the objective). As we mentioned earlier in the section, many of the speech and language pathologist’s diagnostic tests have been adapted from psycholinguistic tasks employed to test hypotheses about language representation and processing under artificial laboratory conditions. Hence there’s a real danger that, just as in second language testing, there could be either under-determination or overdetermination of the patient’s language abilities.

So as a complement to such test results the careful practitioner will collect and analyse a natural sample of discourse with the patient. Sometimes it will be appropriate that the interaction is with a family member or someone else familiar with the patient, rather than with a healthcare professional, who, no matter how sympathetic to the needs of the patient, may not be able to strike up a completely natural and unthreatening conversational relationship. For the same reasons, it might be more appropriate for the sampling and testing to be carried out in the familiar surroundings of the patient’s home rather than the sterility of a clinic. Furthermore, the extent and nature of the disability may well only be assessable in language-modulated interaction, as in cases of pragmatic language impairment. To provide all potentially relevant data, then, samples would need to be collected in real or simulated social contexts. One useful tool for assessing children’s ability to negotiate discourse and recover from inevitable temporary setbacks is to use a map task (Merrison and Merrison, 2005), similar to those used in task-based instruction for additional language learning. In this approach to assessment, the child draws a route on a map on the basis of instructions from the therapist, whose own copy of the map differs with respect to the location and/or inclusion of various landmarks. Conversation analysis techniques are then used to assess the nature of the pragmatic impairment and also as a basis for subsequent therapeutic interaction.

People with pragmatic language impairment have a neurological disorder which affects their ability to use language for appropriate and meaningful communication in social contexts. It is associated with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Assessment and Linguistic Diversity

In the urban centres of developed nations there will increasingly be large numbers of second language users, normally ethnic minorities. When members of these communities are referred to a language pathologist, he or she must be especially sensitive to aspects of linguistic and cultural variation which might, if ignored, compromise or derail effective assessment measures. The Clinical Guidelines of the UK’s Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, for example, are very clear on this danger:

Liaison with bilingual personnel will assist the Speech & Language Therapist in differentiating linguistic and cultural diversity from disorder.

Liaison with bilingual personnel will assist the Speech & Language Therapist in differentiating linguistic and cultural diversity from disorder.

Assessment of the individual’s complete communication system will prevent confusion of normal bilingual language acquisition with communication disorders in bilingual children.

Assessment of the individual’s complete communication system will prevent confusion of normal bilingual language acquisition with communication disorders in bilingual children.

Cultural and linguistic bias have in the past led to the misdiagnosis of language and learning difficulties in bilingual populations. Bilingual children from ethnic minority populations may be unfamiliar with assessment procedures, may expect to speak a certain language in one situation and may respond only minimally to adult questions.

Cultural and linguistic bias have in the past led to the misdiagnosis of language and learning difficulties in bilingual populations. Bilingual children from ethnic minority populations may be unfamiliar with assessment procedures, may expect to speak a certain language in one situation and may respond only minimally to adult questions.

(RCSLT, 2005, p. 15)

As we saw in Chapter 8, it is sensible to view bilinguals as speakers with a single communication system which spans two languages, rather than as linguistic schizo-phrenics. Hence, in the assessment of language disorders the RCSLT goes on to recommend that ‘[a]ssessment of an adult’s complete communication system will identify which elements are language specific and which elements are affected across the whole system’ (RCSLT, 2005, p. 15). In line with our discussion of dialect and register variation in Chapter 2, assessment of language abilities and competences should be conducted from the perspective provided by diglossia. In other words, language pathologists, like language teachers, test-writers and other applied linguists, need to appreciate that differences in clients’ externalization of language do not imply language deficit or pathology. The US National Aphasia Association has a Multicultural Task Force which contributes to this endeavour by coordinating and disseminating information on aphasia and clinical practices in different languages and cultures, including bilingual communities.

Recognition of diglossic situations raises the general issue in diagnostic assessment of just what the ‘benchmark’ should be for ‘normal’ language, against which the patient’s knowledge and abilities should be compared. (For obvious reasons, this will also be a problem in the measurement of recovery.) The idea might be confusing to non-linguists: surely it’s obvious what ‘normal English’ or ‘normal Korean’ is? (And if the linguists haven’t worked this out yet, then what have they been up to all this time?) Well, the answer – as so often in science – is that it’s not so straightforward. Recall our discussion of ‘standard English’ in Chapter 2, where we attempted to establish that there is not just ‘one’ English, and that it’s even less tenable to suppose that there are ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ versions of any language. For example, if Joban were a speaker of Panjabi in the UK, he might use a version of the language which differs from the ‘standard’ form used in print and by privileged groups in Pakistan and India. Martin et al. (2003), for example, suggest that the novel lexical and lexicogrammatical forms they found in the spontaneous speech of Panjabi-speaking youngsters in the West Midlands (mostly due to influence from English) make language assessment difficult. They conclude (Martin et al., 2003, p. 262) that ‘[t]raditional descriptions of Panjabi can no longer be used as target forms for “normative” comparison with speakers of new varieties of British Panjabi’. And it’s a two-way street, of course: the global presence of World Englishes, influenced reciprocally by L1 phonological and grammatical substrates, ensures that the issue will be high on the agenda for language pathologists throughout the Inner and Outer Circle countries.

Assessing Children’s Problems with Language

In the case of developmental disorders, additional assessment problems arise, since the benchmark of ‘the language’ is unavailable not only for the reasons just discussed, but also because the patients – children – haven’t had the chance to fully acquire it yet! You may be thinking that the appropriate yardstick might then be supposed to be what is ‘normal’ for a child of that age. But this can sometimes be a difficult standard to judge, especially in the early years of acquisition, when the detection and assessment of language disorders can actually lead to the most positive outcomes. This is because of the great variability and pacing of language acquisition: although psycholinguistic research has shown clearly that children follow the same series of milestones (in roughly the same order and at roughly the same intervals), the maturational plan unfolding in the child’s brain is not a computer programme, and the social contexts in which each child grows and learns are unique. Detailed guidance for parents is abundant on the internet and in self-help books, and, although useful, can give the impression that these milestones are universal laws rather than average tendencies (Harris, 2004). The US National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD, 2010) provides a lengthy checklist in its ‘How Do I Know If My Child Is Reaching the Milestones?’ section, which parents can use to determine whether their child’s language and speech are developing ‘on schedule’. If any points on the lengthy list are answered in the negative, the parent is advised to talk to their doctor. So, for example, they state that a child between twelve and seventeen months ‘[s]ays two to three words to label a person or object’, and yet the research shows that many normal kids don’t start to produce their first words until after eighteen months (Fenson et al., 1994).

The upshot for language pathologists is that, in the case of babies and infants, where any case history will be brief, a really comprehensive assessment is going to be paramount following diagnosis of a language-related disability. Since a child is not yet a mature human being, their motor control, language system, general cognition, socialization and theory of mind will all be underdeveloped or at only a rudimentary stage of development. It is thus impossible to carry out the kinds of diagnostic and assessment procedures we saw in the case of Joban, since they presuppose a preceding state in which the person was a ‘normal’, fully developed language user.

13.4 Treatment

The whole point of viewing language pathology as a component area of applied linguistics is, of course, that the collected knowledge and experience of the relevant academic disciplines and health professions may ultimately be used by practitioners to alleviate the many serious language-related problems faced by people with the sort of disabilities we’ve seen so far in this chapter. We therefore spend this section looking at the kinds of intervention available and the extent to which they are effective.

The range of treatment and management programmes is, perhaps unsurprisingly, almost as varied as the array of disorders identified. The degree of success of any particular intervention will depend, in part, on the accuracy of the specific diagnosis and integrated assessment of the client. And vice versa: ‘[assessment should] contribute to a measurable baseline for treatment against which the outcome of any intervention can be measured’ (RCSLT, 2005, p. 15). Thus assessment and treatment go hand in hand, and both must be individualized and flexible, rather than routinized and dogmatic. This in turn requires that practitioners be ‘action researchers’ in their own clinics, testing hypotheses and assessing outcomes, just as we saw with language teachers in their classrooms (Chapter 9). Lesser and Milroy make this point eloquently in their book on aphasia treatment:

[T]he hypothesis-testing method … sees the work to be carried out with each patient as a mini-research exercise … The only gap between the ‘researcher’ and the ‘applier’ … is in the time each can devote to this study. The practising clinician contributes to the development of the field, and brings to it the benefit of an extending and intimate knowledge of the continuing nature of the disorder, rather than receiving and applying prescriptions formulated elsewhere.

(Lesser and Milroy, 1993, p. 240)

Treatments can tackle different aspects of the client’s language-related problem, and it’s important to clarify at the outset that they’re not all carried out by speech and language therapists. In the case of disorders with a clearly identified organic cause, surgical procedures or pharmacological therapies will often be recommended and will be administered by physicians, not linguists. Cleft lip and palate, for example, can be treated through reconstructive surgery. For other options, little more than self-help advice may be needed from the experts who make up the professional team. Take augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) resources, such as the use of technology which makes linguistic messages coded in one modality available in another. These may deliver a potential solution (if only partial) for people who have loss of, or damage to, one of the modalities. Although there are many language pathologists whose primary expertise and occupation is with AAC aids, some quite sophisticated technology is now available to anyone with a computer and connection to the internet: the BBC’s ‘My Web, My Way’ website, for example, shows blind and sight-impaired users how to convert text to speech or to make text larger. Adobe Reader and Microsoft Word both convert text into speech. Working in the other direction, the latest voice recognition software can ‘train’ a computer to transcribe oral language into written form, although current versions still require a bit of punctuation assistance from the speaker – check out NaturallySpeaking 10 on the internet (Nuance, 2008). Another company sells ‘scanning pens’ for dyslexics, which read aloud words from printed text, display them in larger text in the barrel of the pen and also read aloud definitions (and cross-references within them) from the Concise Oxford English Dictionary.

Augmentative and alternative communication helps people with communication impediments to communicate more effectively, using alternative modalities (such as gesture), specially designed symbol systems (like Braille) and/or communication devices (e.g. speech synthesizers).

Much speech and language therapy happens in schools, and these days it is teachers and teaching assistants who often take on ‘front-line’ assessment and treatment responsibilities (usually in coordination with therapists, working according to a ‘consultative model’ of provision; see Law et al., 2002). In most developed nations, for example, students with dyslexia are educated along with their peers, according to the ‘inclusive model’ championed in UNESCO’s Salamanca Statement, as discussed in Chapter 7. Effective management of dyslexia in the primary classroom has contributed to the popularity of phonics, especially in UK schools, as we noted in Chapter 6. (We also observed there, however, that an over-emphasis on sound-based literacy learning is not in the interests of non-dyslexic students.) Teacher-led activities to aid children with dyslexia often emphasize multisensory activities, using colours, textures and movement, and can include tasks like the ones we saw used for assessment according to Stackhouse and Wells’ (1997, 2001) psycholinguistic profile or the PALPA tests. They can be incorporated into games or play (Figure 13.5) and other motivating and entertaining activities.

Figure 13.5 Playing therapeutic language games (copyright Jenny Loehr. All rights reserved)

The Serpentine Gallery in London, for example, has worked with the leading British charity Dyslexia Action and a local artist to create an online suite of ‘learning resources’ to create ‘alternative learning spaces’ in the classroom through art. Called NEVERODDOREVEN (a rather artistic palindromic play on words itself!), the site provides numerous suggestions for activities in the regular classroom of children aged five to seven.

Therapists’ more direct intervention with patients and carers may be separated into two broad types, associated by Lesser and Milroy (1993) with psycholinguistic and pragmatic models in linguistics. As we saw in section 13.4, it was psycholinguistic models of normal language processing that first led therapists to conduct the kinds of assessment tests we discussed there. Such tests also provide the basis for targeted intervention to restore and/or improve the specific aspects of language performance detected. Pragmatic approaches, on the other hand, adopting a ‘social model’ of therapy, take into account the whole spectrum of abilities required for successful social communication and stress the collaborative nature of language use. Bearing in mind once more that the objective of applied linguistics is ultimately to help people solve problems, we should be extremely wary of engaging in the kind of confrontational debates which drive advances in theory. It should be apparent that for the therapist it is not a question of which approach is the correct one (psycholinguistics in the white corner, pragmatics in the red!), but rather what combination of approaches and tools will best help a particular client. Of course such eclecticism must be principled and based on measurable outcomes (just as we insisted on in Chapter 9for language teaching methods). But if we can liberate ourselves from the spell which makes us blind to the dual social-biological nature of language, we will no doubt reach the intuitive conclusion that more often than not a complementary psycholinguistic/pragmatic approach will hold the greatest potential benefits for patients. In what remains of this section we take a look at some of the options these approaches provide.

Thankfully, in no case of language disability is the entire linguistic system compromised. Since we (think we) know quite a lot about the various components and subcomponents of the system and how they interact with other domains, both social and psychological, it surely makes sense to exploit this knowledge and treat the specific mental processes directly if we can. There are two major provisos, however: (1) the assessment must be accurate; and (2) positive outcomes must be documented to justify the further use of the treatment. These points and caveats are illustrated well in Pascoe, Stackhouse and Wells (2005), reporting the case of a child whose speech is characterized (in part) by reduction of consonant clusters and missing final consonants, so that fish is pronounced [vi] and pram is pronounced [bae]. The authors document the use of a psycholinguistic ‘phonotactic [syllabic structure] therapy’ which progresses from isolated words through to connected speech. The intervention programme pinpoints relevant details of phonological competence for intensive practice through games and activities. These correspond to performance-level deficits identified at the macro-level by the Speech Processing Profile discussed in section 13.4.

Although psycholinguistic, linguistic and medical approaches can often detect and sometimes successfully treat the specific linguistic problem of a given patient (or its cause), recovery is seldom complete. The ‘pragmatic approach’ responds to this concern and is thus ‘pragmatic’ in the non-specialist sense. But it is also consistent with the academic field of pragmatics, which analyses language as a system embedded in social contexts (rather than ‘just’ a fancy biological symbol-crunching machine). On a daily basis, language users experience not just the psycholinguistic encoding and decoding of messages, but also the use of language as a psychosocial and emotional resource, as well as a badge of personal identity and membership in a range of communities and groups. Thus, the effects of language disability go beyond the purely physiological and psycholinguistic.

Language pathologists must always take into account the whole person, and not just their specific organic or functional disorder. Take the case of a profoundly deaf two-year-old child of deaf parents who are fluent users of American Sign Language (ASL). The parents consider several options:

Figure 13.6 A cochlear implant (Source: US National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders)

A cochlear implant is a tiny device embedded under the skin behind the ear, which is used to bypass the damage to the cochlea – the hollow, spiral bone structure in the inner ear which transforms acoustic energy into auditory nerve impulses – and transmit sound via an alternative route to the auditory nerve.

Although the sound transmitted by a cochlear implant is not identical to normal speech sound, many users are able to hear almost normally. So which option should the parents opt for? The first will mean that their son will grow up as a member of the parents’ language community, and probably also of the larger culturally Deaf community, adding English (in this case) as an additional language of wider communication through literacy. The second option (if the surgery is successful) is to have the child join the hearing community, and to become an ASL–English bilingual via sound.

Clearly, the decision has linguistic ramifications. A two-year-old start with speech is rather late and could have negative consequences, and the child may already have been exposed to sign, from her parents and others, from birth. In both cases, the child will have the capacity to start to learn language normally, either through speech (with the implant) or through sign (from the parents) or both (using resources like the sign language/spoken language online dictionaries for children mentioned in Chapter 10). But beyond language, this is also a pragmatic and cultural choice, including the promise of sign/aural bilingualism. For many in the Deaf community, it is also a profoundly political matter, and language pathologists and applied linguists working with deaf children and families will need to be sensitive to strong feelings about language and identity. (To find out more, the website Inside Deaf Culture provides a useful ‘resource for the Deaf-friendly community’ in the UK.)

We used this example to illustrate the need for practitioners to consider factors that go far beyond specific impairments to the linguistic system or modalities for language use, but, of course, not all treatment options involve such stark choices. Treatments must take into account, and try to diminish, the personal frustrations that many patients will experience in their attempts to communicate. And this is especially so in cases like aphasia after a stroke, where often the rest of the person’s cognitive capacities are left untouched. It’s hard to imagine the levels of stress, anxiety and anger of a middle-aged person who from one day to the next finds herself unable to put her ideas into speech, after a lifetime of doing so. She can’t wait for the research to provide therapies which will ‘cure’ or ‘heal’ her, because she needs to continue communicating with others on a daily basis. Hence she must develop compensatory strategies, a resource we have already discussed in the context of additional language learning, in Chapter 9. Patients can, for example, be helped to develop repetition strategies to be used in verbal interaction, so that they give themselves time to formulate an appropriate response. They may also be coached in formulaic responses, the same unanalysed chunks of language that can ‘jump-start’ effective discourse in beginning language learners and which serve as building blocks for the latest automatic translation systems. People with aphasia are pretty good at the appropriate use of discourse markers (Simmons-Mackie and Damico, 1995), a finding consistent with Oliver Sacks’ observation that although his aphasic patients were language-impaired, they still conserved a strong notion of communicative effectiveness (indeed some have enhanced abilities in this sphere).

Finally, we should point out that within a ‘social model’ of therapy which views the client holistically, as a participant in social encounters and routines, barriers to communication are caused not only by the disability itself but also in the way others respond to it. A revealing demonstration of this is provided by Dijkstra et al.’s (2010 [2002]) analysis of nursing-home discourse between aides and residents with dementia. The study found that the aides used ‘facilitative’ techniques such as information cues, encouragements (like ‘Go on’) and repetitions more with early-stage than with late-stage dementia residents, ‘where they are needed most’ (Dijkstra et al., 2010 [2002], p. 155). The authors suggest that aides might be trained to use more effective communication techniques to help residents with utterance-level cohesion and coherence.

13.5 Roles for Applied Linguists

Once more, knowledge, awareness and sensitivity regarding language and its use are key factors in the success of language pathology, and applied linguistics plays a major role in creating and disseminating the relevant knowledge, as well as promoting awareness and fostering sensitivity in the health and caring professions, the educational sector, government, the media and the public at large. Aside from training to become a language pathologist (for resources, see the companion website), applied linguists in general can take on some of the following roles and responsibilities:

educating students, parents, teachers, the media, policy-makers and the public at large about the existence of language-related disabilities, how they affect the people that have them and how those who interact with them can, if necessary, modify their behaviour as appropriate to the situation;

educating students, parents, teachers, the media, policy-makers and the public at large about the existence of language-related disabilities, how they affect the people that have them and how those who interact with them can, if necessary, modify their behaviour as appropriate to the situation;

conducting research and making recommendations about how to modify institutional interactional behaviour and language practices to allow people with language-related disabilities to participate as fully as possible in public discourses and daily life, including school and the workplace;

conducting research and making recommendations about how to modify institutional interactional behaviour and language practices to allow people with language-related disabilities to participate as fully as possible in public discourses and daily life, including school and the workplace;

combating the prejudices surrounding disability and particularly the widespread beliefs which equate language disability with low intelligence or psychosis;

combating the prejudices surrounding disability and particularly the widespread beliefs which equate language disability with low intelligence or psychosis;

contributing to the design and development of assessment and treatment instruments, including neuropsychological tests, discourse analysis and AAC aids;

contributing to the design and development of assessment and treatment instruments, including neuropsychological tests, discourse analysis and AAC aids;

collaborating with other applied linguists – language planners, literacy teachers, bilingual educators, additional language teachers, interpreters, lexicography software developers, advocates for the reform of legal language, etc. – to take into account the needs of clients of language pathology and to understand that they are their clients too.

collaborating with other applied linguists – language planners, literacy teachers, bilingual educators, additional language teachers, interpreters, lexicography software developers, advocates for the reform of legal language, etc. – to take into account the needs of clients of language pathology and to understand that they are their clients too.

At the beginning of this chapter we pointed out that, of the various specialized disciplines that constitute the field of applied linguistics, it is language pathology that deals with the ultimate physical realities of human language: the ‘string[s] between each word and its matching thing’, in the words of the Welsh poet Gwyneth Lewis. As the chapter has progressed, we hope you have also come to appreciate that the biology of language can’t be dissociated from the sociology of language. If we are to help solve problems experienced by people with language-related disabilities, we must abandon narrow orthodoxies (whether cognitively or sociologically oriented) and strive to understand our clients from multiple perspectives. As we’ll suggest in the final chapter (Chapter 14), a major role for all applied linguists will be to advocate this cooperative and inclusionary approach ever more widely and effectively.

Activities

Further Reading

Ball, M. J., Perkins, M. R., Müller, N. and Howard, S. (eds) (2008). The handbook of clinical linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ferguson, A. and Armstrong, E. (2009). Researching communication disorders. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Oates, J. and Grayson, A. (eds) (2004). Cognitive and language development in children. Oxford: Blackwell/Open University.

Roddam, H. and Skeat, J. (2010). Embedding evidence-based practice in speech and language therapy: International examples. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. and Howard, D. (2005). A cognitive neuropsychological approach to assessment and intervention in aphasia: A clinician’s guide. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.