The simplest way to climb the ladder and take yourself one step closer to the peak, is to get yourself promoted! But what’s the best way to get promoted? Obviously, your artwork is one area, and the other is your level of professionalism, or the way you operate with your teammates and other departments. But how is this all measured; how do you know if you’re doing well?

Over a year your performance and development will be tracked, encompassing the highs and lows, conduct, artwork, precision, decision making, time keeping, asset tracking and whether you take too many coffee breaks. If your boss misses some things, their friends and team no doubt will pick them up.

Your company will use an employee review system, which is both for you and your company. Armed with the information collated about you, your boss can accurately assess your performance. Of course, you want to know where you are doing well (pats on the back are always welcome) but also the areas where you can improve. It’s a chance to discuss bothersome issues or situations with your Lead and really get a good idea of your development.

Either your Lead Artist or Art Director (AD) will conduct the review (or both), but chances are, until this point you’ve had little chance to sit down with them and discuss things that matter to you; they’ll have been super busy. Via reviews, you’ll have at least one opportunity a year, maybe even two, to have a face-to-face chat.

• The yearly review – This is the formal one, where performance, salaries, promotions, and bonuses are decided, all the important stuff.

• The mid-term review – This is the ‘may, or may not happen’ review, where you discuss progress six months into the role (see also the probation section of Level Two). Some companies choose not to as it takes extra time for the managers and HR department. It’s more of an informal check-in.

As I mentioned, your Lead/AD has the task of collating information, sifting, comparing, and categorising against the company’s vision of good or bad. The best part is, regardless of where you go, what country or company, everyone is looking for the ideal employee so the categories are very similar (usual caveat – everyone does things slightly differently!):

1. Communication and teamwork

2. Quality and creativity

3. Knowledge and skills

4. Commitment and reliability

5. Productivity

Each section of the Personal Development Review (PDR) is evaluated. Both you and your manager fill in the review form to record both sides of the evaluation story. The process goes something like this:

• For each category, you can self-grade or comment on yourself depending on the system.

• Your manager takes your comments and information into account and writes their own thoughts on your performance. They might have information from other staff, which contributes to forming an accurate picture.

• You meet to discuss what you’ve both written.

• Based on the conversation, you’ll be given a performance assessment.

• The five sections are graded based on company guidelines.

• Grades might be A-E, 1-5, or strongly agree all the way to strongly disagree.

• Your manager submits the form to HR, where it’s reviewed again and stored in the company’s system.

The grading sadly isn’t a universal system, and different companies operate different methods. The system appears to be wholly subjective, and while some managers will mark hard and low, others you’ll find mark high and easy, which obviously can give some artists an unfair advantage. But not all is lost!

As a final check for fairness, HR and studio managers review the PDRs for consistency. They’ll be on the lookout for managers marking too hard or for no good reason. Part of the balancing process is to take the final numbers/rankings and make them fair and consistent across the team/studio.

Some companies operate a 360˚ review feedback system, whereby your boss reviews you, you review your boss, and your team and colleagues also have input. Don’t be naive like young Paul Jones was. Your comments are not anonymous, the reviewer (your boss) can tell from the language used, the issues raised and the overall style of your review. Don’t go hell for leather writing about how your manager is completely useless and should not be in charge of people. It only gets you into trouble!

TIP: There are ways of saying what you think and still being professional. It’s part of developing your soft skills.

Now you know the basic framework of the PDR, let’s dive deeper and look at what’s involved in each of the categories. With this, you’ll have an inside track on what your company looks for and how you can improve your own skillset ahead of review time.

The first of our five categories sounds straightforward enough, but what do these words mean in the workplace? When it comes to your review what will you be judged on? If you’re to succeed, you need to know what kind of situations arise and how to deal with them.

I’m only scratching the surface here, so to delve deeper, I would highly recommend reading books dedicated to the subject. But I’ll try and break this down into what matters day to day.

At work, there are different modes of communication. As you climb the ladder, you’ll be more and more visible; your company will want more from you and you’ll want to consider altering the style and content of your communications. You might already be tailoring your content and not even be aware of it.

Communication types

Your working life is going to require a mix of verbal and written communication, and depending on your personality, it’ll veer more one way or the other. I’m an introvert who has learned some extravert skills, but my natural tendency is towards the written word. However, I know I need to keep communications up with my team, and face to face is much stronger for building relationships in the workplace.

• Written – Emails and chat software are everywhere. They are part of the environment and are highly useful, being quick, simple, expressive (you can tack on an emoji), and immediate (you can get the answer you need quickly). The downside is that the tone of emails can get lost, because people can interpret content differently.

• Verbal – Face-to-face communication is always going to win when it comes to making connections and solving difficult issues, especially delicate or personal ones. Video calling has become ever more important in a world of distributed workflows, and while it is not as good as being there in person, it has massive advantages. When it comes to global events, even with reduced costs (no travel needed), you can work with talent from all over the world. It also provides greater flexibility for recruitment if you are happy to work this way.

Types of communicators

As you gain experience, you’ll notice more and more how people interact, how they communicate and, most importantly, how their style affects you and vice versa.

As an inexperienced artist, I remember blundering my way through, I was who I was, said what I would normally say, didn’t temper it to the person or the situation. I was the introverted bull in the china shop. I’d like to think of myself as assertive these days, but sometimes the old ways try to creep back in. Everyone is a work in progress.

Above I mentioned assertiveness. Of the four types, that’s the favoured personal style within most organisations and my preferred option. There are another three that go alongside it, and we’ll look at them in turn now and how they operate.

• Assertive – Clear and direct, with no disrespect to others. Assertiveness is often confused with aggression because you’re asking for what you want and being your own advocate. However, as an assertive communicator, you are also open to discussion or compromise and you value other people’s needs as well as your own. To be assertive does not mean your way is the only way. Your tone and how you say or give feedback is just as important as the content. You deal in facts and not generality or exaggeration.

• Aggressive – Your needs take priority over others with a no compromise and no regard for the other person. This can often be ‘My way is right; your way is wrong’. As an aggressive communicator, you can often be defensive or hostile, lacking empathy for other solutions and dominating the situation. Your view on things is correct, everyone else is stupid. You may resort to the blame game, criticising rather than looking for the underlying problems and offering open solutions.

• Passive – The opposite of assertive. You won’t push your own ideas forward, rather you’ll follow someone else’s. Decisions are deferred to others, you have trouble expressing your feelings and needs, which can lead anger to build up, creating tension, and you actively avoid confrontation. It can leave a person vulnerable to abuse in the workplace through bullying, overwork and being the digital donkey, meaning they carry the majority of the load rather than it being shared, or they only get the menial parts of the game pipeline to work on.

• Passive Aggressive – A mixture of passive and aggressive. You give with one hand and take with the other. You appear calm on the surface, but it is masking hidden aggressiveness, while anger builds under the surface. You appear helpful but often leave others feeling undermined, confused, or resentful while you do nothing to help the situation and can actively make it worse behind the scenes.

These communication styles are like flavours, you might be spicy, bitter, mild or a bit of everything. Your communication style affects the people around you, you’re part of a team remember? Your Lead or AD will be looking for specific qualities. Let’s do a quick round of questions and answers to quantify what your reviewer might be judging you on.

What is good communication?

As a Junior, good communication could look something like this; you ask pertinent questions and listen to the answers, making notes to avoid having to ask the same questions later. When you have a problem you try to find a solution before asking, and this way you are better informed. You let your Lead know if there are any problems and don’t leave it to the last minute. You click ‘yes’ to meeting invites so organisers know who is coming. You can explain your workings in team reviews, clearly and concisely, and you don’t waffle on. You don’t pretend to know everything.

As you rise through the ranks, communication skills and nuance get more important. Your involvement with other departments will be greater, so being able to communicate ideas, thinking, priorities, levels of risk and becoming a solution provider are paramount to getting ahead. Naturally, this will be delivered in an assertive manner and without being manipulative.

There are people in the organisation who will test you, unknowingly, and part of your journey is to figure out how to work with them. You might not like a person, but you don’t have to be unprofessional; they might have good information but are spiky or poor at delivering it. You’ll need to take the nuggets of information and let them carry on, unless you are their manager of course, in which case you’ll want to address their issues to foster a better working environment.

What is good teamwork?

In an industry that attracts introverts, teamwork can be a foreign concept initially. People like to hunker down, headphones on, and sit in their bubbles. Being a strong artist does not automatically make you a team player. Going back to the Everest analogy in section 2.1, you don’t get to the top on your own, you’ll need a support system.

A good team player is someone who works well with others. They can work on their own, but also provide support, by listening or helping others with problems and offering solutions. This isn’t a do it all day, every day, kind of thing, it’s a when the occasion requires it. We all have our own schedules and deadlines to hit anyway. If a problem is too big, you might suggest that artist takes it higher up, to a Senior or their Lead, it’s important you don’t take it on. Another facet of a good team player might include owning up to a mistake you have made, and not throwing one of your team ‘under the bus’. Be the grease, not the grit, to your Lead. As a professional artist you help solve problems, not create them, either overtly or behind the scenes by complaining and moaning in the break room.

As a team player you contribute to building a trusting environment, where peers know they can trust you with tasks, help and feedback. You help them up when they are down and celebrate the small wins as much as the large ones, which people often lose sight of. A simple thank you for any task goes a long way, especially in this industry where large portions of work can be taken for granted.

TIP: Everyone needs to let off steam, it’s natural, but even on a Friday night at the bar, if you find yourself part of the crowd complaining and undermining other staff, stop and think about what you are doing, because by doing this you are contributing to a negative culture. Problems are not solved this way, so look for ways to improve the situation actively and in an assertive manner. Be the grease not the grit!

Next up are the areas you care most about, the driving force of any artist. Creation! To build something out of nothing and craft away until the asset shines; that’s the quality aspect. Creativity and quality share a happy little home in an artist’s head, it’s what makes you get up in the morning, switch on the PC and get crafting, day in, day out.

Without this dynamic duo (quality and creativity), game designers could still make a game, but I’m 99% sure it would look dull and uninspiring (sorry designers!)

So, assuming you bring your A game each day, when it comes to review time and you are judged on quality and creativity, what’s the metric? Can it be quantified, or is it subjective and all in the eye of the reviewer? Plus, what happens when you don’t feel the love and feel a need to jump start your artistic self?

How high is high when it comes to quality?

For a Junior’s role, the quality bar is set lower. But as you rise through the ranks, you’ll have years of knowledge and experience to fall back on, so even if stuff does go wrong, you know in the back of your mind that you can pull it all together. You only get to the Principal role by being a leader in your field.

• Experience – There’s only one way to gain experience, or as my old colleague Texas Pete used to say, ‘log the hours’. There’s no escape; do the work and push through the barrier of making mistakes. When you’re learning new software or skills, making mistakes feels less painful, as it’s offset by the good feelings of achievement and creating something fresh.

• Time – To craft a quality asset you need time, and if you don’t have time, you need a toolbox of shortcuts at the ready. As your experience grows, so will your toolkit, enabling you to spend less time wondering about process and dedicate more time to creativity and delivering high quality work.

• Skills – Initially, it’s about an asset moving through its pipeline. Your Lead will be evaluating progress, noting whether it’s a smooth or bumpy transition. Did lots of things go wrong, did it take twice as long as expected, how did you cope with the challenges? In terms of artwork, you’ll be judged on your skill in taking an image and converting it to 3D, to following direction, maintaining the artistic vision, scale, proportion, form, visual balance, contrast, colour, material definition, shader construction and usability (does the asset work for the game, for design and art?).

• Tenacity – Determination is what you need, and bags of it. You’ll hit problems, perhaps with the game tech, the engine, naming conventions, rigging errors, collision meshes, designers being unhappy with something, colours too saturated, style not quite correct, texture too large, UV islands inefficient, I could go on, but what would be the point? It’s all about finding a way to fix the issue, and if you can’t, find help, then fix it.

Fostering creativity

At every position on the artistic career ladder, there’s opportunity for creativity, and the higher you go, the greater the opportunity for creative freedom.

I’m not talking about going rogue and making artwork that doesn’t work for the game. The higher you go, naturally the more experienced you’ll be. Your head will be full of ideas and techniques and ways to improve your own art, and you create inspirational artwork with little assistance. Roles such as the Senior and Principal Artist, for example, have the skills to take what they know and really push the thinking forward, complementing the Art Director’s vision.

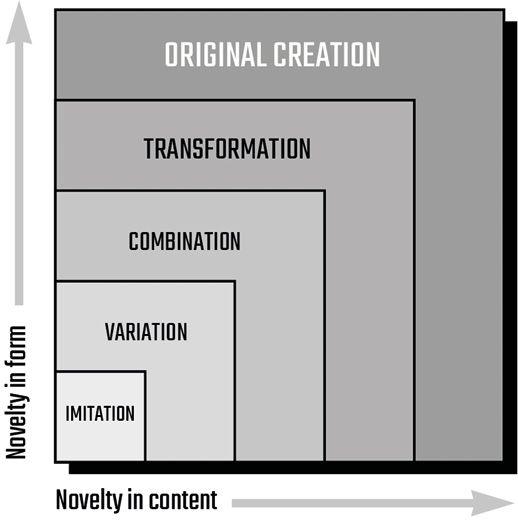

When it comes to the all-important review time, these skills, along with artwork and decision making will be evaluated. Figure 14 has been adapted to describe your journey and development in our industry (original source Peter Nilsson, 2011. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lH9wkpvBkW-bNOkzpBVX15EvpWcKohmK/view).

Figure 14. Development of the creative skillset

Junior Artist – Imitation. At this stage of your career, all your effort is devoted to learning the pipeline and content creation methods. There is less emphasis on creating something new, and more on duplicating and replicating. Can you create assets in the prescribed style? Can you get an asset through the pipeline and into the game without errors?

Mid-level Artist – Variation/Combination. Based on your pipeline knowledge and the art style, you’re able to take ideas (maybe just verbal, no concept art) and create variations on a theme. Building on the confidence gained in your first year, you are hungry for more and ready for bigger challenges. With guidance from your Lead and AD you can deliver full assets that help expand and develop the game.

Senior Artist – Combination/Transformation/Original Creation. Stepping into the world of original creation, you’ll have a broad and deep skillset, meaning you can take whatever you’re given and build it out from the ground up if need be. You have the confidence and art knowledge to take that scrappy, loose single sketch you were given and turn it into a full level, character group, or band of crazy zombies each with unique weapons, and it runs at the target frame rate.

Principal Artist – Original Creation. You take all the above and roll it into one. You can create something from nothing with the confidence that it’ll look amazing. The Principal helps drive the Art Director’s vision based on a chat and a few images for reference. You can help bind the artwork to the design and deliver an early experience for the player, develop new art techniques and pipeline alterations for future game engine development, or advance tool sets to make the art team’s life easier. Fewer complications for the team equals more artwork and faster iteration.

Your Lead will be looking at all these areas. While not normally defined, or at least, I’ve yet to see a company lay it out in black and white like this, these are the notes that they’ll mentally be looking to measure you against, to see how you are developing.

TIP: Be open to learning, from whomever is willing to offer up hints and tips and tricks, young or old, junior or senior, designer or artist, because everyone has experience from which you can benefit.

Your knowledge and skills are vital to levelling up, that’s a no brainer, right? Most artists focus on artwork, which makes sense, as it’s more tangible and if you don’t know something, I bet you can find a tutorial on it. These would be ‘hard skills’. On the opposing end is something wrigglier and harder to get your arms around (for some), namely the soft skills. If you want to rise through the ranks, you’ll need bags of both.

Hard skills

These aren’t things that are hard to learn, most are easily teachable and measurable. Think of what you have on your resume, the courses you’ve taken, the classes finished, the software learnt and to what level. The games industry requires a huge number of hard skills that require your attention. How you gather, learn and the speed at which you develop them will directly affect your rise through the company.

At the start of your career, this is about learning the pipeline. As you progress, focus shifts to pushing content through the pipeline faster and more efficiently. It’s just as important to diagnose how to fix a broken asset as it is how to make something from scratch.

Skills are easily measurable by a Lead Artist. Over time, they’ll see how you shape up using new software, creating assets with or without assistance, evaluating if you’re prone to mistakes or able to improvise, how accurate your work is technically, how close to the art and design brief are you, or whether you make good choices in your art fundamentals. These are all hard skills.

Soft skills

Juniors and Mids are often preoccupied with the hard skills. But soft skills are the opposite of hard skills, they’re subjective. You might know them as interpersonal skills. We’ve already covered communication, which is the biggest of the soft skills, but others include teamwork, flexibility, motivation, collaboration, problem solving, empathy, positivity, open mindedness, and emotional intelligence.

It would be a mistake to assume that the older or more experienced the artist, the better their soft skills. The danger for some can be a lack of awareness that their soft skills aren’t as strong as the industry requires. A seasoned effective Lead Artist or AD will be able to spot these habits and direct them towards something more positive.

To climb that ladder and reach the peak, you need just as many soft as hard skills. When you reach management level, it will all be about negotiation. After all, who are you negotiating with? People. People like you.

No, this isn’t some sort of wedding vow. Your company does want artists who are committed to the cause, turning up day after day, reliably pumping out artwork and getting the game made. But it’s never just that straightforward, is it?

To be promoted you want to be the person who can deliver, hitting deadlines and providing quality assets. Put simply, are you trustworthy?

• Time keeping – Do you arrive on time and work your hours? Do you go the extra mile when asked or when just a few extra minutes can save the rest of the team hours?

• Office attitude – Are you a helper or a hinderer? Do you give and take, or just take?

• Assets – Are you hitting the quality mark and on time, is your work accurate?

• Integrity – When you say you’ll do something, do you and is it of the required quality? Are you aware of the impact on your team if you don’t get the work completed?

• Agility – How flexible are you, can you swap onto different tasks or do you require a more linear flow of work?

• Communication – Do you communicate clearly and ahead of time? Being pro-active when the unforeseen happens is much better than hoping to the end that ‘it’ll all work out’.

• Peers – Do your peers see you as reliable, are they working with you or against you?

• Estimates – How well do you estimate tasks, scope, scale and time?

As you gain rank, these factors remain but the stakes get higher, your tasks become more complex and multi-threaded as you work with more departments. The knock-ons of your decisions are greater because of the greater number of people they touch.

TIP: When it comes to estimating the time for creating an asset, it’s best to add some extra, to account for any errors or problems (they always happen). Don’t over inflate but do give yourself a buffer, because it’ll reduce your stress and make you more effective.

It’s fair to say that everyone wants to be productive. But as the saying goes, being busy doesn’t necessarily mean you’re productive. So, if you aren’t measured by the mouse click or tap of the pen, what does your manager look for?

First, let’s consider what makes one person more productive than another. To answer that we need to ask another question, ie what is productivity? Productivity is a way to measure efficiency. If you are efficient at what you do, you are getting results by achieving your goals in less time and with less effort.

For an artist, a single asset is composed of a hundred smaller tasks, each one dependent on the other, so a mistake early on has repercussions. While it might be fixed, that comes at a cost of more work, time and money. While it sounds bad, this is natural at the start of any creative process, especially in games.

As we’ve covered before, making artwork is half creative and half technical problem solving. Let’s look at some areas I think form some of the building blocks of a productive day.

Motivation – This massively influences how productive someone is. An artist engaged with a project can overcome huge hurdles if they’ve fully bought into the project. For this to happen, normally someone must be happy with the art, the leadership, the company and, not only that, see a future and are committed to building it one asset at a time. They feel appreciated and their effort is recognised. They feel good about themselves and their team and, put simply, love their job.

Time – Some artists (ahem, me sometimes), like to put in extra hours. If you like your job, you can’t help it, you’re doing what you love, so why not push a little harder to see what you can squeeze out of your day; just one more asset, one more tweak. But as you know, I don’t recommend burning out, it’s better to make your day productive by focusing, working smart and then going home on time. Balance is key, you want to be keeping that internal creative bonus jar topped up by doing things other than work.

Experience – Experience plays a large part in how much work you can deliver. The Senior and Principal Artists are the heavy lifters of the team. Junior and Mid-level Artists are still building their pipeline knowledge and figuring out how they like to work, learning the best processes, discovering which actions cause mistakes and which make their lives easier. Sadly, unlike the Matrix movie, you can’t just download the info; it’s about building on your successes.

Support – If you feel supported, you feel recognised and that your work is valued. You’re far more likely to be motivated. Artists can fall into box-ticking mode when they aren’t motivated; work might get done but it won’t be their best, providing lacklustre assets.

Planning – If you’re someone who plans your work in advance, you’ll come out on top in the end. It can be tempting to stampede in and ‘get making stuff’ but it’s better to pause, plan and then execute, having noted tricky areas in advance. Doing your homework means that the final execution will be quicker and smoother.

Multi-tasking – It’s official! People can’t multi-task or context switch as some call it. Hopping between chats and image browsing, or Netflix and assets, takes its toll. Every time you switch, you lose your momentum and break your line of enquiry. It’s best to keep focused in blocks of time (45 minutes) and then take a short break. You aren’t a machine; there’ll be periods where you’re more effective and some when you slow down. It’s natural, so go with the flow and make the most of your up time.

Boundaries – It’s ok to say no, but as an artist, you need to know how. A simple tactic is to say ‘Sorry, I’m in the middle of something right now, can I get back to you later?’ This defines your boundary as you might be unable to interrupt your artistic flow. Doing this won’t offend the person asking, but if they look like they might crumble without help, you can still decide to break off and assist them.

Ok, that’s five for five. I hope this has given you an insight into what you’ll be judged on by your Lead Artist and Art Director. While I imagine it feels overwhelming trying to digest this, my advice would be not to try. This isn’t a test; you’ll do what comes naturally at first and only then will you start to notice the gaps in your skillset. From then on, it’s a process of plugging them (sometimes over years). Some of mine are like a leaky bathroom seal, occasionally failing under high pressure, but I’m not going to beat myself up, I’ll just keep plugging away, like you.

We covered the five categories for a reason, an important one. To climb that ladder, you want to get promoted. To get a step closer to it (more normal), you’ll want to have a good review from your direct manager. Known as the PDR (Personal Development Review), you’ll get the lowdown on your progress, where you’ve done well and which gaps need filling.

The PDR meeting – artist edition

We’ll cover this from the point of view of the artist being reviewed (the reviewee) by a manager (the reviewer). Later in the Lead Artist PDR chapter we’ll look at the process of holding a review and what to plan for.

A PDR, delivered well by a good manager, can be a thing of beauty. Both parties emerge beaming, and you feel buoyed by the recognition of your work and progress. Your manager has a warm fuzzy feeling, knowing they’ve made someone’s day just a little bit brighter, because there’s nothing like delivering good news.

Prior to your PDR, ideally throughout the year you’d have had some mini feedback sessions; do this, change that, that’s good, nice job, all things that indicate how you have progressed. In an ideal world, you’ll enter the review and there’ll be no surprises.

You could see the ‘but’ coming, couldn’t you?

Unfortunately, we aren’t in an ideal world and, as you already know, the games industry is one big work in progress. I gave you a glimpse of a good review right at the start, and it’s easy to imagine, isn’t it? You can feel the warm glow from a good review and no dings on your record.

But what happens when you underperform? Worse, you had no idea and you’re sucker punched. If, like me, you didn’t see it coming, it can cause feelings of anger, confusion, or embarrassment. It can be hard to step back and see a way forward. What follows are some reasons I think this happens and what to do about it.

Flawed process

Managers, especially new ones, can shy away from tricky or sensitive issues. Even some seasoned managers will brush them off and hope that the problem magically solves itself, which 99% of the time, it won’t. There are managers that are so busy that they won’t prioritise reviews over their other tasks (again avoiding the problem), while others won’t even notice because their own managers don’t know how to properly manage staff and so it trickles down. Managing people effectively is a whole separate skill.

Minor improvements

The little ding, even if it comes out of nowhere, is harmless. Typically, something will feature on your PDR report as an area to improve upon, like time keeping, create better UV islands, improve shader network, check your work before submitting to the build machine, provide a cleaner layout of Photoshop layers. That kind of thing, all natural and part and parcel of learning your craft and improving in the industry.

Major improvements

For whatever reason, you may end up in a review session and receive feedback on your performance that you didn’t expect or see coming. It’s rare, but it does happen.

Ideally, your manager would have spotted it earlier and brought you in for an informal chat, to soften the blow and come up with ways to improve the situation. How your manager addresses the issues and your relationship with them will have a big impact on the outcome. But the fact you’ve had a heads-up is good; you’ll have time to try and start to resolve the issue before the formal review.

At the time this happened to me it felt very out of the blue. I also found it very confusing, I was being rewarded for over delivering content and quality but being punished for poor team communication. In hindsight I can see why it would happen, I had retreated into my comfort zone and concentrated on what I could control. Communication didn’t come naturally to me and I didn’t know what was expected for the Lead role, no one had ever sat me down and said, this is what we expect.

It’s natural to feel hurt, aggrieved or angry, and want to challenge your reviewer’s opinion, or become demotivated. But regardless of who you are, there are ways of helping yourself no matter how bad you feel or what emotions are being triggered.

• Absorb the blow. Maybe you didn’t see the problem (obviously you didn’t, you would have fixed it if you had!), but your manager has seen it and brought it to your attention. At the time, you can ask for more clarification, but not all of us are level-headed and clear thinking at times of stress, so listen away, take notes and know that you’ll be coming back to this at a later date.

• After your meeting, spend some time reflecting on what happened. Try to figure out what’s being said. If you can’t understand it, that’s ok, it means that you don’t know what’s being asked of you and therefore you need more information. You can’t solve a problem unless you fully understand it. If you want to vent (try and get this over with quickly as it will hold you back from the problem-solving phase), then do it with someone ideally outside the company ranks. You don’t want to be later accused of causing dissent within the company or your team.

• Often when talking to friends, it’s tempting to remain in the echo chamber, where you receive consolation and sympathy. But that’s not the same as solving the problem. Find some trusted colleagues who can safely provide you with candid responses. I’m not saying this will be easy! You’ll want to remain open, professional, and not defensive. You have invited them in, so don’t chase them out!

• Once you feel more settled, it’s time to go back to your manager with some questions. You want to avoid challenging them and things becoming hostile, so your questions should be targeted, clear and precise. For instance, ‘You mentioned that my communications with my teammates didn’t meet expectations, can you clarify where and how you think I could improve so I’m clear and then can focus on improving them?’ And, ‘Would you be able to provide feedback on a more regular basis?’ Once a year I find is too long a span between feedback sessions.

• As part of your PDR, you may come out with some areas for improvement from your manager. Armed with the new information, be the bigger person and draw up a hit list of ways you can tackle the problem(s). When you’re happy, email this to your manager asking them for their thoughts. This way, you have covered yourself and made your manager still feel in control.

• Change is hard. Be kind to yourself. You may change in a direction you didn’t expect. Through your introspection and self-review, you may find that this job isn’t what you want to be doing, you might see a glass ceiling above you or decide you want an organisation that fits more with your style. I’m not saying run away, but acknowledge that sometimes a square peg can’t be squeezed into a round hole, no matter how you try.

TIP: One thing I now do as a manager and you might suggest to yours, is to provide more regular informal check-ins. This way, issues to be solved feel small and achievable, rather than mountainous and overwhelming due to the build-up over time.