In this text, we have taken a look at the concept of regularity and the need to formulate a list of differential diagnoses for each rhythm (see the Beginner’s Perspective box for Chapter 13, Premature Atrial Contraction). In this chapter, we will start to look at regularity as a way to generate the differential diagnosis and to reinforce the concept of the differential diagnosis, which is a very important diagnostic tool.

When it comes to the regularity of the rhythm, the first question we have to ask ourselves is whether the rhythm is regular or irregular. Instinctively, we can quickly discern regularity without giving it much thought. The next fork in our mental road, however, is a bit more troublesome to understand. If the rhythm is irregular, is it regularly irregular, or irregularly irregular. Rhythms that are regularly irregular have some sort of an underlying regular pattern that is broken up periodically by other occurrences. Irregularly irregular rhythms have no discernible pattern or regularity; the resultant pattern is completely chaotic. In arrhythmias, we typically find such chaotic rhythms created when multiple pacemakers fire at their own rates, causing overlapping rhythms.

The concept of regularity and irregularity can be very confusing for beginners, especially the first few times they read about it. A good analogy we have found that really helps to explain this concept is to relate regularity to music and dancing. When a band plays a song, the beat is maintained by the drummer with metronome-like precision. The mind adjusts to this beat quickly, and the entire composition is built around that beat. The result is an understandable piece that is easy to dance to. You move your feet to the beat with ease and without much forethought. Think of how your feet tap out a song when you hear it on the radio.

A regularly irregular rhythm requires a bit more work to dance to because it is not metronome-like in quality. Typically, there is an underlying regular beat to the song that is interrupted by other events that can occur at different times throughout the song. They can be spaced evenly throughout or can occur with no rhyme or reason. The simpler and more predictable the pattern, the better you can dance to the song. Note that even given a complicated pattern, your mind can still work with the song, and you can still have a blast.

An irregularly irregular rhythm, however, has no rhyme or reason to it. These songs, at least for most of us, are just unpleasant to listen to and almost impossible to dance to. They are usually ones where you see the folks jumping around and flapping their arms spastically like they’ve stood on an ant hill for too long. Orderly thought or movement is impossible with these irregular rhythms, and they are definitely not relaxing for most of us.

There are three rhythms that account for almost all the irregular irregular rhythms: wandering atrial pacemaker, multifocal atrial tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation. If your unknown rhythm is irregularly irregular, think of those three first. The finding is almost pathognomonic to them.

Remember back in Chapter 8, Normal Sinus Rhythm, when we talked about how normal sinus rhythm, sinus bradycardia, and sinus tachycardia were a continuum with two arbitrarily decided separation points at 60 and 100 beats per minute (BPM)? Well, let’s apply that same logic to the irregularly irregular rhythms mentioned previously. Wandering atrial pacemaker (WAP) is a rhythm that is irregularly irregular and associated with three or more distinct P waves with different P-wave morphologies and a heart rate of 100 BPM or less. It is a very important rhythm because of the concepts that underlie its formation. In this rhythm, we have at least three pacemakers scattered in various locations in the atria. This condition gives rise to three or more separate P-wave morphologies, each with their own PR intervals and each firing at their own variable intrinsic rate.

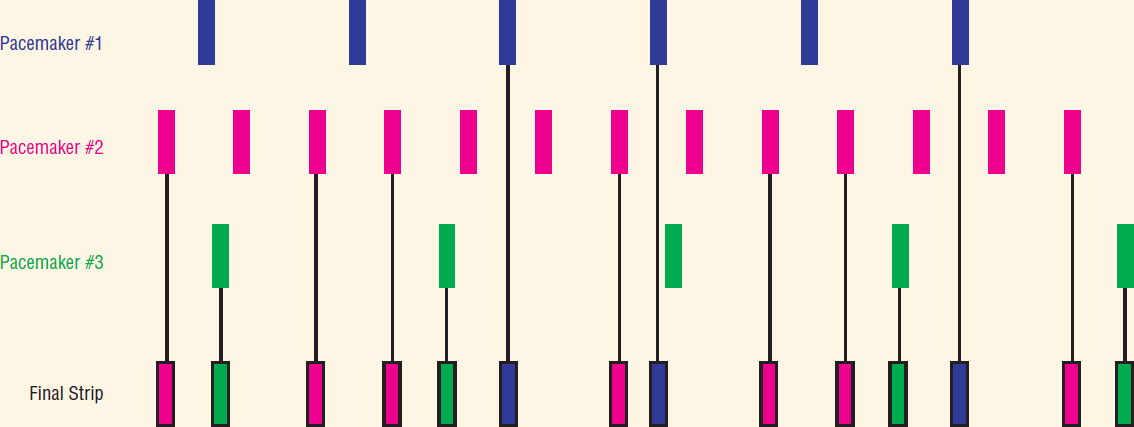

Inset of Figure 17-04.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

The monitor or ECG machine does its best to interpret the various pacemakers on a single strip and ends up simply placing or overlapping them on each other. The net result of these variable rates is an irregular rhythm with varying degree of overlap. P-on-T phenomenon is common to these rhythms, and so are fusion complexes. To express this point, let’s look at three different pacemaker sites by themselves, as seen in Figure 17-4. If isolated, each one of these pacemakers would express its own intrinsic rate. It is important to keep in the back of your mind that just as a premature atrial contraction (PAC) resets the sinus node, these ectopic beats keep resetting and resetting the sinoatrial (SA) node almost continuously. Because of the overlap of the three or more rates, there is no logical sequence of regularity anywhere on these strips.

Just as we saw in the sinus rhythms, the rate can be affected by other variables, such as lung disease. If the ectopic beats fire more quickly, the rate of the resulting rhythm will eventually rise over 100 BPM. At this point, the rhythm is known as multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT). If, as we shall see in future chapters, there are many, many pacemakers, each P wave would be able to capture only a small amount of atrial real estate before reaching refractory walls that would extinguish that depolarization wave. The net result is that the atria are not captured by any one particular pacemaker completely. Mechanically, this situation leads to the atrial muscles having hundreds to thousands of individualized contractions, giving the appearance of a “bowl of worms.” No active pumping occurs to move blood out of the atria; nor does ventricular overfilling to maximize cardiac output. This “fibrillating” rhythm is known as atrial fibrillation (AF).

As we can see, these three rhythms have a similar underlying mechanism and are the list of differential diagnoses of the irregularly irregular rhythms. So, how does this diagnosis play out clinically? You are looking at a strip. You notice the rhythm is irregularly irregular. You immediately think, “Is it WAP, MAT, or AF?” Your next question is, “Are there P waves?” If the answer is no, the diagnosis is AF. If the answer is yes, then it is either WAP or MAT. You next ask, “What is the rate?” If it is 100 BPM or less, the diagnosis is WAP. If it is above 100 BPM, it is MAT.

—Daniel J. Garcia