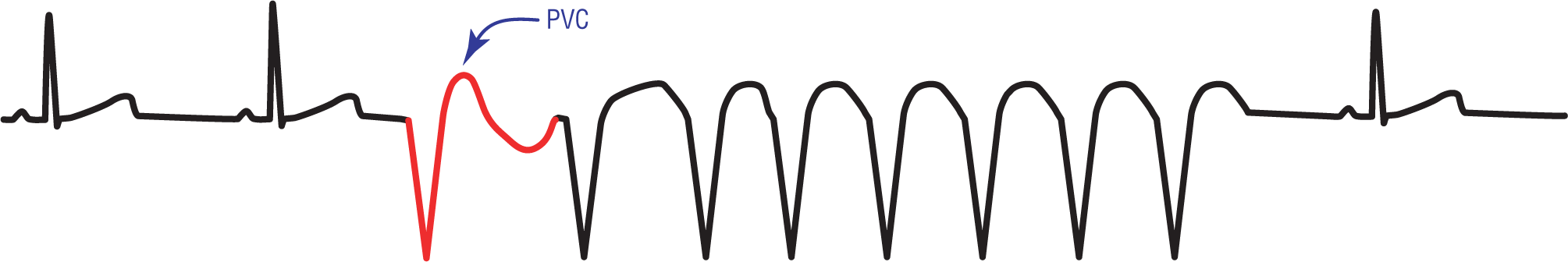

Figure 32-15 A PVC triggers an eight-beat run of NSVT.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nonsustained Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), or more specifically nonsustained monomorphic VTach, is an incidental finding in some people obtaining Holter monitors for palpitations or other reasons. Electrocardiographically, it is described as the occurrence of three or more consecutive, morphologically similar, ventricular complexes occurring at an intrinsic rate of over 100 BPM. By definition, the rhythm spontaneously terminates at less than 30 seconds. Clinically, it is a significant rhythm because of the symptoms with which it can present but, more importantly, it can be a harbinger for sustained VTach or ventricular fibrillation. Both of these potential rhythms are life threatening.

Most patients typically have 3- to 10-beat runs or salvos of NSVT. The runs are usually triggered by a PVC with the same general morphology seen on the strip (Figure 32-15). In general, patients with NSVT have a higher frequency of PVCs at baseline than patients who do not have the rhythm abnormality.

Figure 32-15 A PVC triggers an eight-beat run of NSVT.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

The clinical manifestations of NSVT can be anything from an asymptomatic expression to transient hemodynamic compromise, depending on the length of the run. The last part of that statement is very important, because short runs can typically be well tolerated. As a matter of fact, most episodes are so short as to cause only minimal, transient symptoms.

When the run lasts longer than a few seconds, however, it can essentially cut off perfusion of the main organs, including the brain and the heart itself. A few seconds of nonperfusion to the brain could result in syncope. Other common clinical presentations include lightheadedness, near-syncope, palpitations, and visual disturbances.

Additional Information

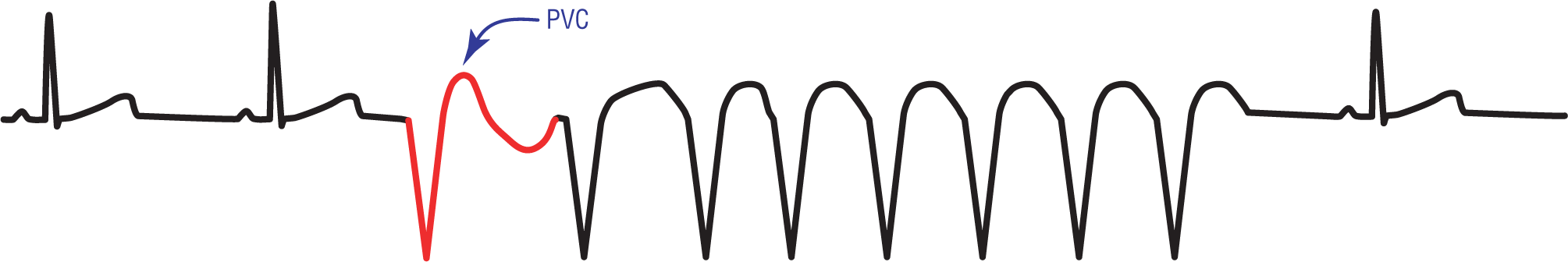

Concordance of the Precordial Leads

A full 12-lead ECG of a patient with VTach will often show concordance of all of the QRS complexes in the precordial leads. What we mean by this is that the main direction of all of the QRS complexes will be in the same direction, either all positive or all negative (Figures 32-16 and 32-17), in all of the chest or precordial leads (V1 through V6). The size of the complex is not important, just the direction and orientation of the QRS complexes.

Figure 32-16 Positive concordance in VTach.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Figure 32-17 Negative concordance in VTach.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Concordance is yet another useful tool in evaluating the differential diagnosis of a wide-complex tachycardia. It is not definitive proof of the arrhythmia, but it is highly indicative of VTach.

Additional Information

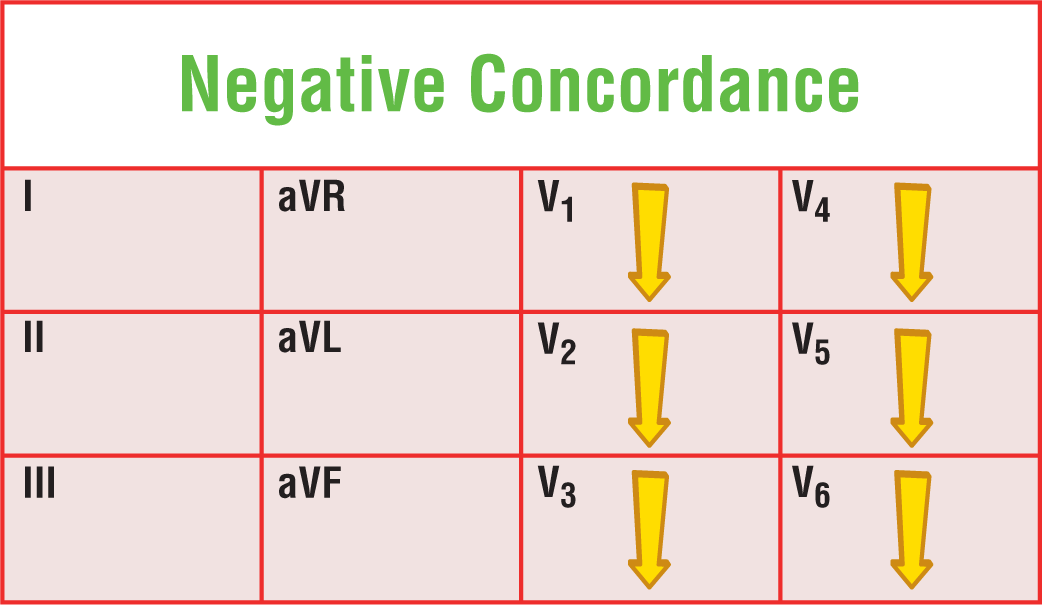

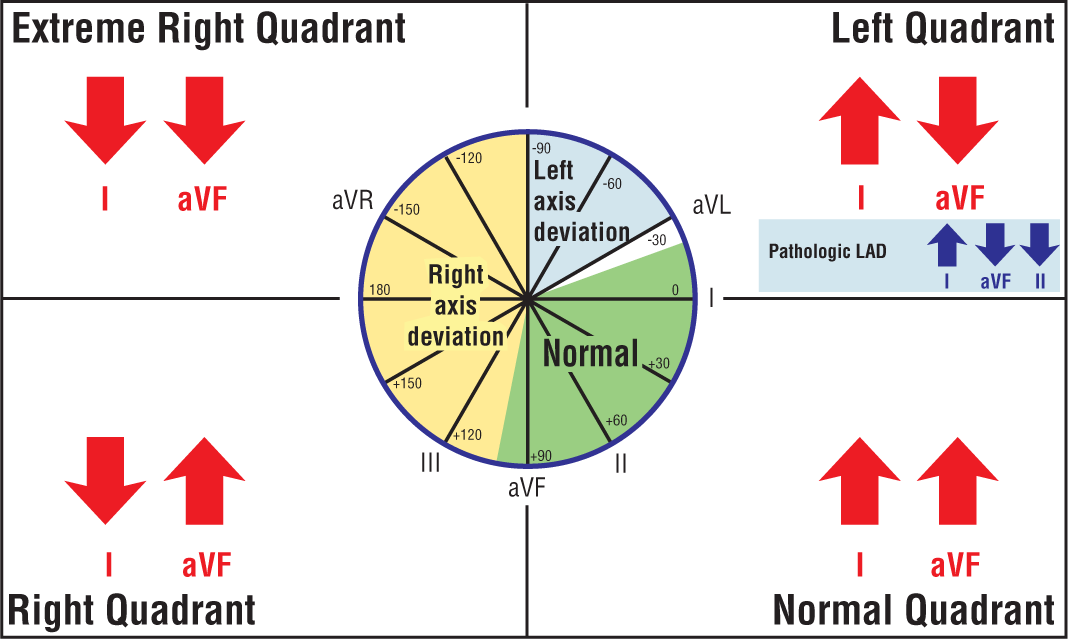

Axis Direction and Ventricular Tachycardia

A full 12-lead ECG can also give you another useful bit of information. The axis in VTach is often found to be in the extreme right quadrant (Figure 32-18). This is not a common quadrant to find the main ventricular axis in any patient, so its presence is indicative of a vector that is originating in a bizarre ectopic site. Frequently, these sites will give rise to VTach. Once again, an axis in the extreme right quadrant is not definitive proof of the arrhythmia, but it is highly indicative of VTach.

Figure 32-18 The axis in VTach is often found in the extreme right quadrant. In order to isolate the axis to that quadrant, look at the QRS complexes in leads I and aVF. If the QRS complexes are negative in both of those leads, the axis has to be in the extreme right quadrant.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

DescriptionMorphologically, the complexes all resemble each other. NSVT may be slightly irregular if the run is short. Longer runs will stabilize and will show a regular cadence. A quick way to decide whether a short run of irregular wide complexes is due to NSVT or intermittent atrial fibrillation with aberrancy is to compare the complexes to the PVCs that are usually found on the strip near the run in question. If the morphology is identical, or nearly identical, to the PVCs, then it is NSVT. If the run does not resemble the PVCs, it could easily be atrial fibrillation with aberrancy.

Additional things to look for include the onset of the run. If the run is triggered by a PVC, it strongly favors NSVT. Longer strips and full 12-lead ECGs are extremely helpful to look for the direct and indirect signs AV dissociation. The presence of Josephson’s sign or Brugada’s sign favors the diagnosis of VTach. We will look at the differential diagnosis of VTach much more closely elsewhere in this text, namely Chapters 34 through 37.