► Breathlessness and low sats emergency

| ► Airway |

Check airway is patent; consider manoeuvres/adjuncts |

| ► Breathing |

If no respiratory effort—CALL ARREST TEAM |

| ► Circulation |

If no palpable pulse—CALL ARREST TEAM |

►► Call for senior help early if patient is deteriorating. Use emergency call bell to summon help quickly—don’t leave the patient.

• Sit patient up

• 15L/min O2 in all patients if acutely unwell

• Monitor pulse oximeter, BP, defibrillator’s ECG leads if unwell

• Obtain a full set of observations including temp

• Take a brief history if possible/check notes/ask ward staff

• Examine patient: condensed RS, CVS, ±abdo exam

• Establish likely causes and rule out serious causes

• Initiate further treatment, see  pp. 277–278

pp. 277–278

• Venous access, take bloods:

•FBC, U+E, LFT, CRP, bld cultures, D-dimer, cardiac markers

• Arterial blood gas, but don’t leave the patient alone

• ECG to exclude arrhythmias and acute MI

• Request urgent CXR, portable if too unwell

• Call for senior help

• Reassess, starting with A, B, C …

• In COPD/known CO2 retention, rapidly titrate down O2 to lowest flow to maintain normal sats for this patient (usually 88–92%). Beware of CO2 retention and have a low threshold for repeat ABG.

► Life-threatening causes

• Asthma/COPD

• Pulmonary oedema (LVF)

• (Tension) pneumothorax

•MI/arrhythmia

|

• Pneumonia

• Pulmonary embolism (PE)

• Pleural effusion

• Anaphylaxis/airway obstruction.

|

Breathlessness and low sats

► Worrying features RR >30, sats <92%, systolic BP <100mmHg, chest pain, confusion, inability to complete sentences, exhaustion, tachy/bradycardia, silent chest.

Think about ► Life-threatening causes of respiratory failure See Table 8.1; Most likely COPD/asthma, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema (LVF), PE, MI; Others Pneumothorax, pleural effusion, arrhythmia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, metabolic acidosis, anaemia, pain, panic, foreign body/aspiration; Chronic COPD, lung cancer, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, TB.

Ask about Speed of onset, cough, change in sputum (quantity, colour), haemoptysis, wheeze, chest pain (related to movement, pleuritic), chest trauma, palpitations, dizziness, difficulty lying flat, recent travel, weight loss; PMH Cardiac or respiratory problems, malignancy, old or exposure to TB; DH Inhalers, home nebulizers, home O2, cardiac medication, allergies; SH Smoking (pack-years), pets, exercise tolerance, previous/current occupation (asbestos exposure). PE risk factors Recent surgery/immobility/fracture/travel/hospitalization, oestrogen (pregnancy, HRT, the pill), malignancy, previous PE/dvt, thrombophilia, varicose veins, obesity, central lines.

Obs Temp, RR (11–20 is normal), BP, HR, sats (should be >94%1), O2 requirements (improving or worsening?).

Look for Ability to speak full sentences, confusion, cyanosis, CO2 flap, tremor, clubbing, rashes, itching, swollen lips/eyes, raised JVP, tracheal shift and tug, use of accessory muscles, abnormal percussion, unequal air entry, crackles, stridor, wheeze, bronchial breathing, swollen/red/hot/tender legs, swelling of ankles, cold peripheries.

Investigations PEFR If asthma suspected (may be too ill); blds FBC, U+E, LFT, CRP, D-dimer (if PE suspected and Wells score <4  p. 284), cardiac markers, blood cultures; Sputum (May need physio or saline nebs to help) inspect and send for M,C+S; AFBs if TB risk; ABG (

p. 284), cardiac markers, blood cultures; Sputum (May need physio or saline nebs to help) inspect and send for M,C+S; AFBs if TB risk; ABG ( pp. 598–599), keep on O2 if acutely SOB; ECG (

pp. 598–599), keep on O2 if acutely SOB; ECG ( pp. 586–588); CXR (

pp. 586–588); CXR ( pp. 596–597); portable if unwell, though image quality may be poor; Spirometry Should be done once the patient has been stabilized to help confirm the diagnosis (

pp. 596–597); portable if unwell, though image quality may be poor; Spirometry Should be done once the patient has been stabilized to help confirm the diagnosis ( p. 600).

p. 600).

Treatment Sit all patients up and give 15L/min O2 – this saves lives. This can be reduced later since CO2 retention in COPD takes a while to develop. Check sats and ECG in all patients:

• Stridor—call an anaesthetist ( p. 291)

p. 291)

• Wheeze—give nebulizer ( p. 279), eg salbutamol 5mg ±ipratropium 500micrograms STAT (drive by oxygen or air as appropriate)

p. 279), eg salbutamol 5mg ±ipratropium 500micrograms STAT (drive by oxygen or air as appropriate)

• Unilateral resonance, reduced air entry ±tracheal deviation and shock—consider tension pneumothorax and treat urgently ( p. 285)

p. 285)

• Asymmetrical coarse crackles,↓air entry, bronchial breathing—consider pneumonia ( p. 282)

p. 282)

• Symmetrical fine crackles,↓air entry,↑ JVp—consider LVF ( p. 288)

p. 288)

• Normal exam—consider PE, asthma, cardiac, and systemic causes.

Table 8.1 Common causes of breathlessness

|

History |

Examination |

Investigations |

| COPD |

Usually smoker, change in productive cough, worsening wheeze |

±wheeze/crackles, ±cyanosed/pursed-lip breathing, look for infection and pneumothorax |

CXR hyperexpanded, flat diaphragms; exclude pneumonia and pneumothorax

ABG; sputum

|

| Asthma |

Known asthma, recent exposure to cold air, allergens or drugs (NSAIDs, β-blockers), viruses |

Wheeze ±crackles, look for signs of infection or pneumothorax |

↓PEFR; CXR; exclude pneumonia and pneumothorax

ABG; eosinophil count

|

| Pneumonia |

Productive cough, green sputum, feels unwell ±pleuritic pain |

Febrile, asymmetrical air entry, crackles, bronchial breath sounds ±↓percussion |

↑WCC/NØ/CRP, consolidation or blunted angles on CXR ( pp. 596–597); sputum MC and S pp. 596–597); sputum MC and S |

| Pulmonary embolism |

PE risk factors, leg pain, ±pleuritic chest pain and haemoptysis |

↑JVP, ↑HR (may be only sign); may have evidence of DVT; can be severely shocked |

↓PaCO2 ±hypoxia on ABGs, ↑D-dimer, CXR often normal |

| Pulmonary oedema |

Known cardiac problems, orthopnoea, swollen legs |

↑JVP, symmetrical fine inspiratory crackles, pink frothy sputum, dependent oedema, cold peripheries |

Cardiomegaly + fluid overload on CXR ( pp. 596–597), ECG may show ischaemia or previous MI pp. 596–597), ECG may show ischaemia or previous MI |

| Pneumo- thorax |

Sudden onset pleuritic chest pain ±trauma. Underlying lung disease and previous episodes or tall, thin, male |

Unequal air entry and expansion, hyper-resonant ±displaced trachea (late) |

Needle decompression of tension pneumothorax; CXR shows pleura separated from ribs |

| Pleural effusion |

Gradual onset breathlessness, ±pleuritic chest pain |

Reduced expansion, stony dull base |

Effusion on CXR |

| ARDS |

Concurrent severe illness |

Hypoxic, very unwell |

New bilateral infiltrates on CXR |

| Anaemia/MI/ARRHYTHMIAS |

Chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, tiredness |

Irregular or fast pulse, shocked, pale |

Abnormal ECG ( pp. 586–588), ↓Hb, ↑cardiac markers pp. 586–588), ↓Hb, ↑cardiac markers |

| ►► Anaphylaxis |

Sudden onset, itching, swelling, urticarial rash, new drugs/food |

Stridor, ±wheeze, shock, swollen lips and eyes, blanching rash |

IM adrenaline, IV steroids ( pp. 484–485); acute and convalescent serum tryptase pp. 484–485); acute and convalescent serum tryptase |

Asthma

A common chronic disease characterized by variable airflow obstruction, inflammation, and hyper-responsiveness that results in wheeze, chest tightness, dyspnoea, and cough.

A common chronic disease characterized by variable airflow obstruction, inflammation, and hyper-responsiveness that results in wheeze, chest tightness, dyspnoea, and cough.

Symptoms Episodic breathlessness, wheeze and chest tightness; family or personal Hx of atopy (hayfever, eczema, asthma).

Signs Wheeze, tachypnoea, silent chest, hyperinflated chest.

Investigations PEFR Reduced in acute setting compared with best or predicted based upon age/height, or diurnal variation on self-monitoring as out- patient; ABG Normal or ↓ PaO2 with a ↓ PaCO2 due to hyperventilation. ►► Beware normal/rising CO2 ?Patient tiring; CXR Hyperexpanded, exclude pneumonia and pneumothorax; Spirometry ↓ FEV1, ↓ FEV1:FVC ratio. Acute exacerbation Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Salbutamol 5mg NEB ±ipratropium 500micrograms NEB and prednisolone 40mg PO (or hydrocortisone 200mg IV). Drive the nebulizer mask from O2 supply, not air. Repeat salbutamol 2.5mg neb every 10–15min and reassess PEFR and sats frequently. Antibiotics if evidence of infection.

►► Severe Incomplete sentences, PEFR <50% of best, HR >110, RR >25.

►► Life-threatening PEFR <33% of best, silent chest, sats <92%, PaO2 <8kPa, normal PaCO2, poor respiratory effort, exhaustion, cyanosis, altered GCS, arrhythmia. ► C all ICU.

►► Near-fatal CO2 retention. ► C all ICU.

► Beware those with previous ICU admissions.

No improvement Call for senior help. Consider:

• Early ICU input/assessment

• Aminophylline 0.5–0.7mg/kg/h, discontinue any oral theophylline and monitor levels (under senior guidance)

• Mg2+sulfate 2g (8mmol) IV over 20min.

Improving Admit those in whom PEFR<75% predicted after 1h therapy; gradually reduce supplemental O2 and step from nebs to inhalers over several days; always check inhaler technique and ensure patient books follow-up with GP 48h post discharge.

Chronic treatment ( OHCM10 p. 182.) See Table 8.2, aiming for minimum treatment resulting in symptom control; monitor PEFR; always check inhaler technique before escalation; ensure allergen avoidance, smoking cessation and co-morbidities (GORD, nasal polyposis, OSA, breathing pattern disorder) identified and controlled.

OHCM10 p. 182.) See Table 8.2, aiming for minimum treatment resulting in symptom control; monitor PEFR; always check inhaler technique before escalation; ensure allergen avoidance, smoking cessation and co-morbidities (GORD, nasal polyposis, OSA, breathing pattern disorder) identified and controlled.

COPD ( OHAM4 p. 186.)2

OHAM4 p. 186.)2

Predominantly fixed airflow obstruction due to loss of elastic recoil in alveoli (emphysema) and narrowing of airways with excess secretions (bronchitis).

Predominantly fixed airflow obstruction due to loss of elastic recoil in alveoli (emphysema) and narrowing of airways with excess secretions (bronchitis).

► Worrying signs ↓ GCS, rising CO2.

Symptoms Breathlessness, cough, ↑sputum, tight chest, confusion, ↓exercise tolerance. NB ↑index of suspicion in (ex-)smoker.

Signs Wheeze, cyanosis, barrel-chested, poor expansion, tachypnoea.

Investigations ABG Often deranged in COPD, with type 2 RF common. Compare with previous samples and pay close attention to FiO2; repeat after 30min in seriously ill patients; CXR Hyperexpanded, flat diaphragm (look for evidence of infection, pneumothorax, or bullae); Spirometry ( p. 600) ↓ FEV1, ↓ FEV1:FVC ratio (<70%).

p. 600) ↓ FEV1, ↓ FEV1:FVC ratio (<70%).

Acute exacerbation Sit the patient up and give the minimum amount of O2 to maintain sats ≥88% (aim for PaO2~8kPa). Give salbutamol 2.5mg ±ipratropium 500micrograms NEB (drive by air, leaving nasal O2 cannulae on under mask if necessary) and prednisolone 30mg PO (or hydrocortisone 200mg IV). Sputum for M,c+S. Get an ABG and CXR (portable if unwell). Use ABG results and clinical observations to guide further management:

• Normal ABG (for them) Continue current O2 and give regular nebs

• Worsening hypoxaemia↑FiO2, repeat ABG <30min, watch for confusion which should prompt a repeat ABG sooner; consider NIV

•↑ CO2 retention or ↓ GCS Request senior help ► urgently; consider:

• ICU input/assessment

• Aminophylline 0.5–0.7mg/kg/h, discontinue any oral theophylline and monitor levels (under senior guidance)

• NIV (Box 8.1).

Antibiotics Consider prescribing antibiotics (eg PO doxycycline or amoxicillin) if the patient has ↑ SOB, fevers, worsening cough, purulent sputum, or focal changes on CXR.

Chronic treatment ( OHCM10 p. 184) Smoking cessation is paramount. Stepwise therapy with inhalers can reduce symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance (Table 8.3). If still breathless despite maximal inhaler therapy, give home nebulizers. If PaO2 consistently ≤7.3kPa (or ≤8kPa with additional risk factors), long-term O2 therapy aiming for a minimum of 15h/d confers survival advantage. Annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccines decrease incidence of LRTI.3 Consider prescribing rescue packs (abx/steroids) to patients for acute (infective) exacerbation. Pulmonary rehab (see Box 8.2).

OHCM10 p. 184) Smoking cessation is paramount. Stepwise therapy with inhalers can reduce symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance (Table 8.3). If still breathless despite maximal inhaler therapy, give home nebulizers. If PaO2 consistently ≤7.3kPa (or ≤8kPa with additional risk factors), long-term O2 therapy aiming for a minimum of 15h/d confers survival advantage. Annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccines decrease incidence of LRTI.3 Consider prescribing rescue packs (abx/steroids) to patients for acute (infective) exacerbation. Pulmonary rehab (see Box 8.2).

Complications Exacerbations, infection, cor pulmonale, pneumothorax, respiratory failure, lung cancer (beware haemoptysis and weight loss).

Box 8.1 Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

Box 8.1 Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

Machines assist ventilation through a tightly fitting mask. Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) used in COPD patients with a pH ≤7.35 and CO2 ≥6.0kPa who have failed to respond to initial medical therapy reduces mortality and length of admission. Patients who need NIV usually stay on the respiratory ward or HDU/ICU. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is not NIV since it does not help with mechanics of ventilation ( p. 288).

p. 288).

Table 8.3 Simplified COPD severity assessment and treatment (GOLD guidelines)

| GOLD stage |

Yearly exacerbations |

Dyspnoea |

Treatment |

Severity of airflow limitation (FEV1 % predicted) |

| A |

1 or less |

Breathless only on strenuous exercise |

SABA or SAMA |

≥80—GOLD 1 (Mild) |

| B |

1 or less |

Having to stop on walking |

LAMA or/ + LABA |

50–79—GOLD 2 (Moderate) |

| C |

2 or more (or 1 hospital admission) |

Breathless only on strenuous exercise |

LAMA + LABA or LABA + ICS |

30–49—GOLD 3 (Severe) |

| D |

2 or more (or 1 hospital admission) |

Having to stop on walking |

ICS + LABA + LAMA (triple therapy) |

<30—GOLD 4 (Very severe) |

Source: data from Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2017 report,  http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wms-GOLD-2017-Pocket-Guide.pdf

http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wms-GOLD-2017-Pocket-Guide.pdf

Table 8.4 Some common inhalers for asthma and COPD

| Drug type |

Medication |

Trade name eg |

Colour |

|

Short-acting β agonist |

Salbutamol |

Ventolin® |

Blue |

| Terbutaline |

Bricanyl® |

Blue |

|

Inhaled steroids |

Beclometasone |

Qvar® |

Brown |

| Budesonide |

Pulmicort® |

Brown |

| Fluticasone |

Flixotide® |

Orange |

| Ciclesonide |

Alvesco® |

Red |

|

Inhaled steroids and long-acting β agonist (combination) |

Beclomethasone/formoterol |

Fostair® |

Pink |

| Budesonide/formoterol |

Symbicort® |

Red |

| Fluticasone/salmeterol |

Seretide® |

Purple |

| Fluticasone/vilanterol |

Relvar® |

Yellow |

|

Long-acting anticholinergic |

Tiotropium |

Spiriva® |

Grey |

| Umeclidinium |

Incruse® |

Green |

| Glycopyrronium |

Seebri® |

Orange |

| Aclidinium |

Eklira (Genuair)® |

Green |

|

Long-acting β agonist and long-acting anticholinergic (combination) |

Vilanterol and umeclidinium |

Anoro® |

Red |

| Indacaterol and glycopyrronium |

Ultibro® |

Yellow |

| Oldaterol and tiotropium |

Spiolto® |

Green |

| Formoterol and aclidinium |

Duaklir® |

Orange |

Box 8.2 Pulmonary rehabilitation

Patients with chronic lung disease who take part in a structured 8–12wk pulmonary rehabilitation programme with a graduated exercise regimen see increased exercise tolerance and improved well-being,4 although this does not reverse pathological processes or improve spirometry. Diet and other lifestyle advice are also covered.

Pneumonia ( OHAM4 p. 166.)5

OHAM4 p. 166.)5

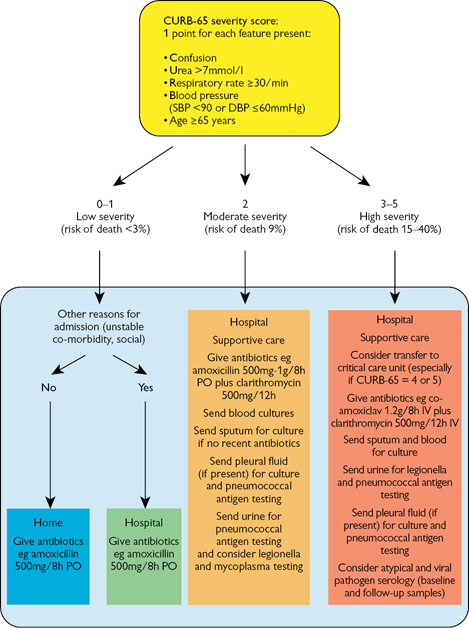

► Worrying signs CURB-65 score ≥3 (see ‘Severity’,  p. 282).

p. 282).

Symptoms Cough, purulent sputum, pleuritic chest pain, breathless, haemoptysis, fever, unwell, confusion, anorexia.

Signs ↑temp, ↑ RR, ↑ HR, ↓sats, unequal air entry, reduced expansion, dull percussion, bronchial breathing.

Severity The CURB-65 criteria (see Fig. 8.1) are a validated set of variables that support (but do not replace) clinical judgement in community-acquired pneumonia on whether to admit.6 In the out-patient setting, omit urea to get a CRB-65 score; patients scoring 0 (and possibly 1–2) are suitable for home treatment.

Investigations blds ↑ WCC; ↑ neutrophils; ↑ CRP; bld cultures. If CURB-65 ≥2; Sputum cultures If CURB-65 ≥3 (or CURB-65=2 and not had antibiotics); Urine If CURB-65 ≥2 test for pneumococcal antigen; if CURB-65 ≥3 or clinical suspicion, test for legionella antigen; ABG ↓PaO2 (±↓PaCO2 due to hyperventilation but not if tiring or COPD); CXR MAY show focal consolidation; repeat at 6wk if ongoing symptoms or high risk for malignancy/empyema.

Treatment Sit up and give O2 as required. Give antibiotics according to local policy or  p. 181 for empirical treatment. Look for dehydration and consider IV fluids. Most patients who require IV antibiotics can safely be switched to PO therapy by day 3.7 Offer a 5d course of antibiotic therapy for patients with low-severity CAP; consider a 7–10d course of antibiotic therapy for patients with moderate and high severity CAP. If symptoms not resolving by day 3, repeat CRP and CXR to exclude pleural effusion/empyema.

p. 181 for empirical treatment. Look for dehydration and consider IV fluids. Most patients who require IV antibiotics can safely be switched to PO therapy by day 3.7 Offer a 5d course of antibiotic therapy for patients with low-severity CAP; consider a 7–10d course of antibiotic therapy for patients with moderate and high severity CAP. If symptoms not resolving by day 3, repeat CRP and CXR to exclude pleural effusion/empyema.

Complications Empyema, respiratory failure, sepsis, confusion.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia  Pneumonia developing ≥48h after admission and not felt to have been incubating at time of admission. Causative organisms will include Gram –ve bacilli (eg Pseudomonas or Klebsiella species, E. coli.) as well as S. pneumoniae and S. aureus (including MRSA). Symptoms and signs can be severe, particularly in frail patients with other comorbidities, and lung necrosis and cavitation may develop. Empirical antibiotic selection should be guided by local policy ±discussion with a microbiologist.

Pneumonia developing ≥48h after admission and not felt to have been incubating at time of admission. Causative organisms will include Gram –ve bacilli (eg Pseudomonas or Klebsiella species, E. coli.) as well as S. pneumoniae and S. aureus (including MRSA). Symptoms and signs can be severe, particularly in frail patients with other comorbidities, and lung necrosis and cavitation may develop. Empirical antibiotic selection should be guided by local policy ±discussion with a microbiologist.

Aspiration pneumonia  Aspiration of gastric contents refluxing up the oesophagus and down the trachea may lead to a sterile chemical pneumonitis. Alternatively, oropharyngeal bacteria may be aspirated causing a bacterial pneumonia. Risk factors include ↓GCS (eg sepsis, anaesthesia, seizures), oesophageal pathology (eg strictures, neoplasia), neurological disability (eg dementia, MS, Parkinson’s disease), or iatrogenic interventions (eg NG tube, OGD, bronchoscopy). At-risk patients can be identified by bedside swallow evaluation (

Aspiration of gastric contents refluxing up the oesophagus and down the trachea may lead to a sterile chemical pneumonitis. Alternatively, oropharyngeal bacteria may be aspirated causing a bacterial pneumonia. Risk factors include ↓GCS (eg sepsis, anaesthesia, seizures), oesophageal pathology (eg strictures, neoplasia), neurological disability (eg dementia, MS, Parkinson’s disease), or iatrogenic interventions (eg NG tube, OGD, bronchoscopy). At-risk patients can be identified by bedside swallow evaluation ( p. 356). Care is supportive, with O2 supplementation, suctioning of secretions, and attention to prevention of further aspiration (involve SALT and chest physio). Empirical antibiotics can be of benefit if bacterial pneumonia suspected (eg persistent fever, purulent sputum)—eg co-amoxiclav 625mg/8h PO or 1.2g/8h IV with metronidazole 400mg/8h PO or 500mg/8h IV.

p. 356). Care is supportive, with O2 supplementation, suctioning of secretions, and attention to prevention of further aspiration (involve SALT and chest physio). Empirical antibiotics can be of benefit if bacterial pneumonia suspected (eg persistent fever, purulent sputum)—eg co-amoxiclav 625mg/8h PO or 1.2g/8h IV with metronidazole 400mg/8h PO or 500mg/8h IV.

Pulmonary embolism ( OHAM4 p. 120.)

OHAM4 p. 120.)

Symptoms Often none except breathlessness; may have pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis, dizziness, leg pain; consider risk factors in Table 8.5.8

Signs ↑ JVP, ↑ RR, ↑ HR, ↓ BP, RV heave, hypotension, pleural rub, ±pyrexia. Tachycardia and tachypnoea may be the only clinical signs.

Investigations D-dimer Will be raised in many situations (infection, malignancy, MI, CVA to name a few) while a normal D-dimer must be interpreted in the clinical context (Box 8.3); ECG (sinus tachycardia commonest finding), RBBB, inverted T waves V1–V4 or S1Q3T3; ABG type 1 RF (↓ CO2, ± ↓ O2) (if large PE); CT-PA Is the definitive imaging modality, though V/Q scan may be used, eg in those with renal failure, pregnancy.

Acute treatment Sit up (unless ↓ BP) and give 15L/min O2. If life-threatening (hypotension +shock) seek immediate senior support, arrange an urgent CT-PA + echo and consider thrombolysis. Otherwise parenteral anticoagulation ( pp. 420–422), eg enoxaparin 1.5mg/kg/24h SC and pain relief; IV fluids if ↓ BP.

pp. 420–422), eg enoxaparin 1.5mg/kg/24h SC and pain relief; IV fluids if ↓ BP.

Chronic treatment Anticoagulation ( pp. 420–422) eg warfarin/ DOAC. Length of treatment will depend on risk factors/context.9

pp. 420–422) eg warfarin/ DOAC. Length of treatment will depend on risk factors/context.9

Box 8.3 Clinical risk assessment for PE

Box 8.3 Clinical risk assessment for PE

PEs are common and potentially fatal, but associated with non-specific clinical signs. The CT-PA offers excellent diagnostic accuracy but exposes your patient to 3.6yr of background radiation, along with nephrotoxic IV contrast medium, while taking up significant resources. So can D-dimer testing help? Remember, the negative predictive value of any test is determined by the prevalence of whatever disease you are testing for: the value of D-dimer testing lies in the excellent negative predictive value when the risk of a PE is low. In those at high risk, negative D-dimer levels do not provide sufficient reassurance.

The Wells score for PE (Table 8.5) is a clinically reliable method of identifying the risk of PE, and hence deciding on further testing.

• Those scoring ≤4 are low risk: test for D-dimers.10 If elevated, proceed to CT-PA; if negative, then consider alternative diagnoses

• Those scoring >4 are high risk: proceed to CT-PA testing and start treatment dose of LMWH.

Table 8.5 Wells score for pulmonary embolism

| Clinical feature |

Points |

| Signs/symptoms of DVT (leg swelling and pain on deep vein palpation) |

3 |

| PE most likely clinical diagnosis |

3 |

| HR >100 |

1.5 |

| >3d immobilization or surgery in past 4wk |

1.5 |

| Previous DVT/PE |

1.5 |

| Haemoptysis |

1 |

| Malignancy (current treatment or treatment in past 6mth or palliative) |

1 |

Source: data from Wells et al. Thromb Haemost 2000;83:358.

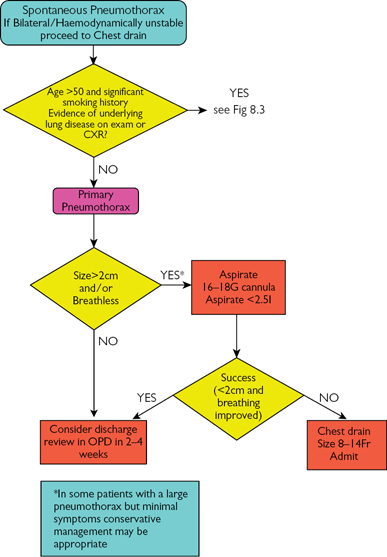

Spontaneous pneumothorax (OHAM4  p. 204)11

p. 204)11

May occur apparently spontaneously (primary) or in the presence of underlying lung disease or injury (secondary).

May occur apparently spontaneously (primary) or in the presence of underlying lung disease or injury (secondary).

Risk factors Primary Tall, thin, male; Marfan’s; recent central line, pleural aspiration or chest drain; Secondary COPD, asthma, infection, trauma, mechanical ventilation.

Symptoms Breathlessness ±chest pain.

Signs Hyper-resonant and reduced air entry on affected side, tachypnoea, may have tracheal deviation or fractured ribs.

Investigations CXR Lung markings not extending to the peripheries, line of pleura seen away from the periphery.

Treatment Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Chest drain/aspiration as directed by BTS guidelines ( p. 286). In essence, primary pneumothoraces can potentially be discharged, while secondary pneumothoraces require admission and either aspiration (

p. 286). In essence, primary pneumothoraces can potentially be discharged, while secondary pneumothoraces require admission and either aspiration ( p. 552) or, more usually, drainage (

p. 552) or, more usually, drainage ( pp. 554–555).

pp. 554–555).

►► Tension pneumothorax

If air trapped in the pleural space is under positive pressure (eg following penetrating trauma or mechanical ventilation) then mediastinal shift may occur, compressing the contralateral lung and reducing venous return. The patient may be hypotensive, tachycardic, tachypnoeic, with unilateral hyper-resonance and reduced air entry; ↑ JVP and may have tracheal deviation away from the side of the pneumothorax. ► This is an emergency, it will rapidly worsen if not treated. Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Treat prior to CXR. Insert a large cannula (orange/grey) into the 2nd intercostal space, midclavicular line. Listen for a hiss and leave it in situ; insert a chest drain on the same side. If there is no hiss, leave the cannula in situ and consider placing a 2nd cannula or consider alternative diagnoses; a chest drain is usually still required to prevent a tension pneumothorax accumulating.

Pleural effusion ( OHAM4 p. 216.)11

OHAM4 p. 216.)11

Excessive fluid within the pleural space reflects an imbalance between hydrostatic and oncotic pressures within the pleural vasculture, and/or disruption to lymphatic drainage.

Excessive fluid within the pleural space reflects an imbalance between hydrostatic and oncotic pressures within the pleural vasculture, and/or disruption to lymphatic drainage.

Causes Pleural effusion may be divided into those causing transudates (where pleural fluid protein <25g/L—tend to be bilateral) pulmonary oedema, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, intestinal malabsorption/failure and exudates (protein >35g/L—may be unilateral or bilateral) malignancy, infection, vasculitides, rheumatoid; if purulent and pH <7.2, this is empyema reflecting infection.

Light’s criteria These help differentiate, especially when protein >25g/L but <35g/L. Consider the effusion an exudate if pleural protein:serum protein >0.5, pleural LDH:serum LDH >0.6, or pleural LDH >2/3 of upper limit of normal serum value.

Symptoms The patient may be breathless with pleuritic chest pain.

Signs Stony dull to percussion with reduced air entry, tachypnoea.

Investigations CXR Loss of costophrenic angle with a meniscus  pp. 596–597.

pp. 596–597.

Treatment Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Investigate the cause; if the effusion is large, pleural aspiration ( p. 552) may relieve symptoms and aid diagnosis (draining >1.5L/24h may cause re-expansion pulmonary oedema).

p. 552) may relieve symptoms and aid diagnosis (draining >1.5L/24h may cause re-expansion pulmonary oedema).

Algorithms for the treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax

Pulmonary oedema ( OHAM4 p. 87.)

OHAM4 p. 87.)

Symptoms Dyspnoea, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, frothy sputum; coexistent dependent oedema or previous heart disease.

Signs ↑ JVP, tachypnoea, fine inspiratory basal crackles, wheeze, pitting cold hands and feet; oedema (ankles and/or sacrum) suggests right heart failure.

Investigations blds (Look specifically for anaemia, infection or MI): fbc, U+E, CRP, cardiac markers; BNP (normal levels unlikely in cardiac failure); ABG May show hypoxia; ECG Exclude arrhythmias and acute STEMI, may show old infarcts, LV hypertrophy or strain ( pp. 586–588); CXR Cardiomegaly (not if AP projection), signs of pulmonary oedema (

pp. 586–588); CXR Cardiomegaly (not if AP projection), signs of pulmonary oedema ( pp. 596–597); Echo Poor LV function/ejection fraction.

pp. 596–597); Echo Poor LV function/ejection fraction.

Acute treatment Sit up and give 15L/min O2. If the attack is life-threatening call an intensivist early as CPAP and ICU may be required. Otherwise monitor HR, BP, RR, and O2 sats while giving furosemide 40–120mg IV ±diamorphine (repeat every 5min up to 5mg max, watch RR) 1mg boluses IV (repeat up to 5mg, watch RR). If further treatment is required, be guided by blood pressure:

• Systolic >100 Give 2 sprays of sublingual GTN followed by an IV nitrate infusion (eg GTN starting at 4mg/h and increasing by 2mg/h every 10min, aiming to keep systolic >100; usual range 4–10mg/h;  p. 203)

p. 203)

• Systolic <100 The patient is in shock, probably cardiogenic. Get senior help as inotropes are often required. Do not give nitrates

• Wheezing Treat as for COPD alongside above-mentioned treatment

• No improvement Give furosemide up to 120mg total (more if chronic renal failure) and consider CPAP (see Box 8.4). Insert a urinary catheter to monitor urine output, ±CVP monitoring. Request senior help. Consider HDU/ICU.

Once stabilized, the patient will need daily weights ±fluid restriction. Document LV function with an echo and optimize treatment of heart failure ( p. 274). Oral bumetanide may be preferred to oral furosemide for diuresis since absorption is said to be more predictable in the presence of bowel oedema, though evidence for this is lacking. Always monitor U+E during diuresis: The heart-sink patients are those with simultaneously failing hearts and kidneys who seem fated to spend their last days alternating between fluid overload and AKI—close liaison with the patient’s GP and palliative care teams is as essential as ever here.

p. 274). Oral bumetanide may be preferred to oral furosemide for diuresis since absorption is said to be more predictable in the presence of bowel oedema, though evidence for this is lacking. Always monitor U+E during diuresis: The heart-sink patients are those with simultaneously failing hearts and kidneys who seem fated to spend their last days alternating between fluid overload and AKI—close liaison with the patient’s GP and palliative care teams is as essential as ever here.

Box 8.4 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

Box 8.4 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

Application of positive airway pressure throughout all phases of the respiratory cycle limits alveolar and small airway collapse, though the patient must still initiate a breath and have sufficient muscular power to inhale and exhale. Pursed-lip breathing has a similar effect, and is often observed in patients with chronic lung disease. CPAP is often used in the acute treatment of pulmonary oedema or the chronic treatment of sleep apnoea (may use nasal CPAP).

SVC obstruction ( OHCM10 p. 528.)

OHCM10 p. 528.)

Symptoms Breathlessness, orthopnoea, facial/arm swelling, headache.

Signs Facial plethora (redness), facial oedema, engorged veins, stridor.

Pemberton’s test Elevating the arms over the head for 1min results in increased facial plethora and ↑ JVP.

Investigations CXR/CT Mediastinal mass, tracheal deviation, venous congestion distal to lesion; Other Sputum cytology for atypical cells.

Treatment Seek senior input early. Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Dexamethasone 4mg/6h PO/IV. Consider diuretics to decrease venous return and relieve SVC pressure (eg furosemide 40mg/12h PO). Otherwise symptomatic treatment while arranging for tissue diagnosis.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) ( OHAM4 p198.)

OHAM4 p198.)

Acute-onset respiratory failure due to diffuse alveolar injury following a pulmonary insult (eg pneumonia, gastric aspiration) or systemic insult (shock, pancreatitis, sepsis). Characterized by the acute development of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and severe hypoxaemia in the absence of evidence for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema.

Acute-onset respiratory failure due to diffuse alveolar injury following a pulmonary insult (eg pneumonia, gastric aspiration) or systemic insult (shock, pancreatitis, sepsis). Characterized by the acute development of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and severe hypoxaemia in the absence of evidence for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema.

Symptoms Breathlessness, often multiorgan failure.

Signs Hypoxic, signs of respiratory distress, and underlying condition.

Investigations CXR Bilateral infiltrates.

Treatment Sit up and give 15L/min O2. Refer to HDU/ICU early and treat underlying cause. Often requires ventilation.

► Stridor in a conscious adult patient

| ► Airway |

Acute stridor—CALL ANAESTHETIST AND ENT URGENTLY |

| ► Breathing |

If poor respiratory effort—CALL ARREST TEAM |

| ► Circulation |

If no palpable pulse—CALL ARREST TEAM |

►► Call for senior anaesthetics and ENT help immediately.

• Do not attempt to look in the mouth/examine the neck

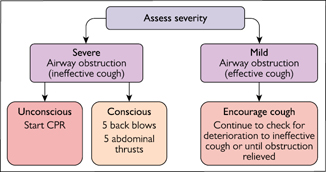

• If choking, follow algorithm in Fig. 8.4

• Avoid disturbing/upsetting the patient in any way

• Let the patient sit in whatever position they choose

• Offer supplemental O2 to all patients

• Fast bleep senior anaesthetist

• Fast bleep senior ENT

• Adrenaline (epinephrine) nebs (5mL of 1:1000 with O2)

• Monitor pulse oximeter ±defibrillator’s ECG leads if unwell

• Check temp

• Take brief history from relatives/ward staff or check notes

• Look for swelling, rashes, itching (?anaphylaxis)

• Consider serious causes (see ‘Life-threatening causes’)

• Await anaesthetic and ENT input

• Request urgent portable CXR

• Call for senior help

• Reassess, starting with A, B, C …

► Life-threatening causes

• Infection (epiglottitis, abscess)

• Tumour

• Trauma

|

• Foreign body

• Post-op

• Anaphylaxis

|

Cough

Box 8.5 Causes of coughs

| Acute |

URTI, post-viral, post-nasal drip (allergy), pneumonia, LVF, PE |

| Chronic |

Asthma, COPD, bronchitis, bronchiectasis, smoking, post-nasal drip, oesophageal reflux, pneumonia, TB, parasites, interstitial lung disease, heart failure, ACEi, lung cancer, sarcoid, sinusitis, cystic fibrosis, habitual |

| Bloody |

Massive Bronchiectasis, lung cancer, infection (including TB and aspergilloma), trauma, AV malformations

Other Bronchitis, PE, LVF, mitral stenosis, aortic aneurysm, vasculitides, parasites

|

Usually, the cause of coughing is obvious (Box 8.5). Chronic (>8wk), unexplained coughing with a normal CXR and the absence of infective features requires a considered approach. Is there diurnal or seasonal variation in coughing (cough-variant asthma; do PEFR diary, lung function testing, and a trial of inhaled steroids)? Is there a history suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux (trial of PPI)? Does the onset of a dry cough follow the introduction of an ACEi (consider an AT II receptor blocker)? Or is there a sensation of mucus accumulation at the back of the throat (consider chronic/allergic rhinitis and ‘post-nasal drip’ and a trial of nasal steroids or antihistamines)?

Haemoptysis Coughing up blood, >500mL over 24h is massive.

Management ABC, establish patent airway; FBC, U+E, LFT, clotting, G+S, sputum C+S and cytology, ABG, ECG, CXR. Sit up, 15L/min O2. Codeine 60mg PO (may ↓cough) If massive Good IV access (≥green), monitor HR and BP, immediate referral to respiratory team for urgent bronchoscopy ±CT thorax.

Bronchiectasis ( OHCM10 p. 172.)12

OHCM10 p. 172.)12

Abnormal and permanently damaged and dilated bronchi caused by destruction of the elastic tissue of the bronchial walls.

Abnormal and permanently damaged and dilated bronchi caused by destruction of the elastic tissue of the bronchial walls.

Causes Cystic fibrosis, infection (pneumonia, TB, HIV), tumours, immunodeficiency, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, foreign bodies, aspiration, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, idiopathic.

Symptoms Chronic cough with purulent sputum ±haemoptysis, halitosis.

Signs Clubbing, coarse inspiratory crepitations ±wheeze.

Investigations FBC, immunoglobulins, aspergillus serology; blood or sweat test (for CF); Sputum C+S; CXR Thickened bronchial outline (tramline and ring shadows) ±fibrotic changes; CT thorax (‘high-resolution CT’) Bronchial dilatation; spirometry; Bronchoscopy for other diagnoses.

Acute treatment O2 ±BIPAP as required, ±bronchodilators ±cortico-steroids. Typical recurrent infections include Pseudomonas (consult local antibiotic guidelines). Chest physiotherapy to mobilize secretions.

Chronic treatment Chest physio, inhaled/nebulized bronchodilators, antibiotics, consider prophylactic, rotating antibiotics if ≥3 exacerbations/yr. NIV and surgery may be considered where medical management fails.

Complications Recurrent pneumonia, pseudomonal infection, massive haemoptysis, cor pulmonale.

Patients with chronic lung disease may normally have sats <92%. 88–92% is a better target. See BTS guidelines on emergency use of oxygen in adults at  www.brit-thoracic.org.uk

www.brit-thoracic.org.uk

NICE guidelines available at  guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101

guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2017 report.  http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wms-GOLD-2017-Pocket-Guide.pdf

http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wms-GOLD-2017-Pocket-Guide.pdf

Summarized at  https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/pulmonary-rehabilitation/bts-quality-standards-for-pulmonary-rehabilitation-in-adults/

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/pulmonary-rehabilitation/bts-quality-standards-for-pulmonary-rehabilitation-in-adults/

NICE guidelines available at  guidance.nice.org.uk/CG191

guidance.nice.org.uk/CG191

Lim WS, et al. Thorax 2003;58:377 full-text available free at:  www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1746657

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1746657

Oosterheert JJ, et al. BMJ 2006;333:1193 full-text available free at:  www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1693658

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1693658

NICE guidelines available at  guidance.nice.org.uk/CG144

guidance.nice.org.uk/CG144

3mth may suffice if low risk (eg 1st PE with identified risk factor now removed); if higher risk (recurrent or unprovoked PEs, or thrombophilia) treatment may need to be long term.

In pregnancy, D-dimer testing is uninterpretable. If clinical suspicion, then a Doppler U/S of leg veins is the safest initial investigation—treat if DVT seen. If this is negative, a half-dose V/Q scan provides an acceptable balance of diagnostic utility with radiation exposure. The risk of CT-PA is not to the foetus (which can be shielded) but to proliferating maternal breast tissue.

British Thoracic Society guidelines available at  https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/bts-pleural-disease-guideline/

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/bts-pleural-disease-guideline/

British Thoracic Society guidelines available at  https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/bts-guideline-for-non-cf-bronchiectasis/

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/bts-guideline-for-non-cf-bronchiectasis/

pp. 277–278

pp. 277–278

Box 8.1 Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

Box 8.1 Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)