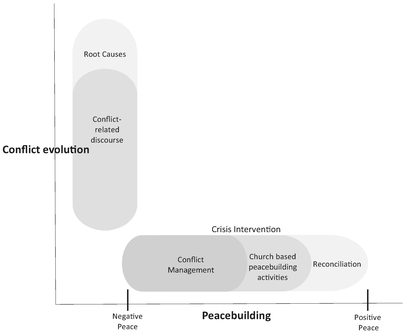

Figure 2.1 Framework of analysis

Source: Adapted from Lederach (1997: 80).

Theory and analytical framework

The following chapter provides a brief outline of the theoretical parameters which inform our research. It reviews key arguments of the relevant literature, lays the conceptual ground for our field research, and develops an overarching framework for the analysis of religious actors in local peace-building efforts, in which it is strongly influenced by the work of Johan Galtung, John Paul Lederach, Roger Mac Ginty, and Oliver Richmond.1

Conflicts occur when involved parties are convinced that their interests and objectives are mutually incompatible (Miller 2005: 22). According to Ellis, the likelihood that a conflict will erupt increases with the presence of a number of basic conditions: first, the conflicting parties have a conscious sense of being integral members of distinct groups (for example, an ethnic or religious group); second, group members feel dissatisfied, or even alienated, when they compare themselves with a collective other; and, third, they believe that their frustration can only be eased by exerting pressure on the collective other, for example by non-violent or violent2 strategies (Ellis 2006: 26).

Ellis’ definition tallies well with Johan Galtung’s broad conceptualization of violence. According to Galtung, violence denotes the “avoidable insults to basic human needs, and more generally to life, lowering the real level of needs satisfaction below what is potentially possible” (Galtung 1990: 292). “Basic human needs” refers to the requisites essential for securing survival, ensuring wellbeing, constructing and maintaining an identity (or identities), achieving or safeguarding freedom, and establishing ecological balance (ibid.: 292). Furthermore, Galtung distinguishes between three types of violence: the first type concerns direct acts of violence such as killing and detention (ibid.: 292); the second type describes structural violence which emerges in heavily skewed social relationships that threaten a group’s attainment of basic human needs through acts of exploitation and segmentation (ibid.: 292); and the third type pertains to cultural violence which refers to “aspects of culture [. . .] that can be used to justify or legitimize direct or structural violence” (ibid.: 291).

Galtung also introduced the well-known distinction between “negative” and “positive” peace, which highlights the protracted and multilayered process of peacebuilding. While negative peace is characterized by the absence of war and physical violence, the attainment of positive peace is more conditional and involves more far-reaching social integration in accordance with basic human needs (ibid.: 292). Both of these concepts are of significance for our research. In the two conflict regions of our study, Mindanao and Maluku, post-conflict church-based peace activities and projects are confronted with societal structures that continue to be beset by structural violence, or in other words, conditions associated with negative or fragile peace, which can easily re-ignite and erupt into manifest violence. Such conditions include the aforementioned phenomena of residential segregation, social and economic discrimination, negative attitudes towards the religion-politics nexus, and stereotyped mindsets towards other religious groups. These conditions generate emotionally loaded, exclusivist or intolerant sentiments; in other words, attitudes that sharply contrast liberal or tolerant mindsets. They may even feature militant elements that denote an uncompromising or fundamentalist set of principles concerning the practice of faith. Arguably, this fundamentalist narrowing can become a breeding ground for future conflicts and hence give rise to new levels of structural or even manifest violence. This study is thus chiefly concerned with understanding how church-based activities can attenuate these vicious circles of narrow mindsets and violent actions, and whether these efforts contribute to more interfaith dialogue, social integration, and, over time, local transformations towards positive peace.

As outlined in the introductory chapter, a large number of contemporary armed conflicts are fueled by religious divides. This feature, which Galtung characterizes as a source and example of cultural violence, points to the question of how the contentious term “religious conflict” can be defined. A useful starting point is Silvestri and Mayall’s identification of two distinct ways to understand religion, differentiating between two major dimensions. The first concerns the substantive understanding that focuses on the content of religion, such as key scriptures, theologies, bodies of doctrine, canonical texts, and values and beliefs (Silvestri & Mayall 2015: 5). The second highlights a functional understanding that discerns what religion “does” to people, for example as a source of identity, morality, and others (ibid. 2015: 4).

The substantive understanding of religion can be framed as a value conflict, which theoretical research on regimes has identified as most resilient to resolution (Efinger, Rittberger & Zürn 1988). Contending values and ideologies often become a source of conflict, not least because they are at the core of social belief systems and group identities. Compromising on substantive values is often perceived by warring parties as a form of capitulation or sociocultural disconnection. As a result, some conflict dynamics and violent outbreaks can be explained by irreconcilable ideas concerning theology and religious doctrines.3 These contestations and clashes can either involve different religions, or they can involve subgroups of one belief system. The latter is well exemplified, for instance, in the continuous tensions between Sunni and Shia Islam that have destabilized the Middle East and other parts of the world.4

While religious bonds and divides are certainly influential, there is also a growing sense that conflicts evincing “pure” or “exclusive” religious motives are rare occurrences. More frequently, religion serves as a “functional” leverage factor, as a catalyst or accelerator of other embedded seeds of conflict. The concept of “religion as function” can be understood, in essence, as a conflict over material goods which, as regime theory argues, are valued in either absolute or relative terms (Efinger, Rittberger & Zürn 1988). Religion in such conflicts serves as the factor galvanizing broad-based popular opposition and resistance against those held responsible for the predicament. In these conflicts, religion is “not the source, but only a resource of conflict.”5 Or expressed differently, such conflicts are not “interreligious conflicts, but conflicts involving religious communities.”6 Contested goods valued in relative terms include most forms of social, economic, and political deprivation. Such conflicts may be more amenable to resolution than value-based conflicts, but general or comprehensive resolutions are also very difficult to achieve (ibid.).

Influential schools of thought in conflict studies seem to corroborate the salience of the second type of religious conflict. One of the earliest proponents of this argument was Michael Hechter in his study on ethnicity in the United Kingdom. For him, primordial identities such as religion and ethnicity will be mobilized when tangible socioeconomic disparities coincide with them, which are perceived by at least one group as relative deprivation. If such disparities are exacerbated by social discrimination and political oppression of a group and hence constitute what Hechter pointedly called “internal colonialism,” the likelihood of religious and/or ethnic strife increases significantly (Hechter 1975). The root cause of religious conflict is thus the accumulated sense of “grievances” of the disadvantaged group. As we will see later, conflict parties and observers of the Mindanao and Ambon conflicts also frequently refer to these root causes (D’Ambra 2011: 98).

Apart from the occurrence of grievances, violence can also be the result of strong materialistic aspirations and desires. Based on a study of 79 large civil conflicts in Africa, Collier and Höffler show that “greed” and “opportunity” are frequently triggers of intra-state conflicts. Greed, frequently epitomized by a war economy, generates material motivations that lead to and prolong armed conflict (Collier & Höffler 2004). While explanations of the long duration of conflicts, especially in Mindanao, also highlighted material causes (Kreuzer & Weiberg 2007; International Alert 2014), in the case of Maluku the emergence of a war economy was – as discussed later – also often mentioned as a reason why violent incidents continued after the 2002 Malino II peace agreement, albeit on a lower scale (Spyer 2002: 31; Panggabean 2004: 423; Böhm 2006: 283, 288, 305, 339; Al Qurtuby 2016: 31).

In a similar vein, Fearon and Laitin identified a number of conditions that seem to increase the probability of intergroup violence and civil war. Their findings show that weak central governments, which are unable to steer financial, organizational, and political affairs, often give rise to instability and violence. In many cases this lack of state capacity has provoked rebellion “due to weak local policing or inept and corrupt counterinsurgency practices” (Fearon & Laitin 2015: 143). Moreover, insurgencies are more likely to occur in places that entail pronounced challenges in terms of topography (rough or mountainous terrain), demography (large and diverse populations), and social proximity (if rebels are closer to local communities than the government). The probability of insurgencies rises even further if rebel strongholds gain access to external funds, training, and safe havens (ibid.: 143).

While these empirical findings highlight socioeconomic and geographical aspects, recent anthropological studies present a more nuanced picture of civil wars that acknowledges that religious norms and sentiments can have far-reaching effects. While not denying certain “objective” material factors such as those highlighted above, they also contend that these sources of conflict are primarily those identified by external observers and, in particular, academics. By contrast, however, the majority of the combatants and the population affected by the violence view the conflict through the primordial lens and perceive it as a religious conflict (Hehanussa 2013: 216; Duncan 2013: 2; Al Qurtuby 2015: 316, 2016: 8). Religion thus lends itself well to what Tambiah has famously termed “focalization” and “transvaluation” (Tambiah 1991, 1996; see also Duncan 2005: 68, 2013: 116–117; Al Qurtuby 2016: 3). “Focalization” denotes a process in which conflict parties “remove understandings of local conflicts from their particular contexts in time and space,” while “transvaluation” describes the incorporation of a local conflict “into a wider, extra-local conflict” (Tambiah 1996: 81; Duncan 2013: 116). As we will see later in the empirical chapters, this is especially the case in the Ambon conflict, and thus constitutes a major obstacle to sustainable reconciliation.

Moving beyond the root causes of intra-state conflicts, the following section focuses on processes of conflict resolution. The period after the end of the Cold War has seen an unprecedented increase in international peacebuilding missions. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the concomitant sharp decline of vetoes against peace missions has increasingly allowed the international community to launch UN-sanctioned peace operations. UN Secretary General Boutros-Ghali’s “Agenda for Peace” initiative in 1992, for instance, became an important milestone for global peacebuilding efforts. It opened new opportunities for reconciliation and served as a platform for the advocacy of what was then called the “peace dividend” (Gupta et al. 2002). In the process, international peace missions have proliferated, increasing from 12 operations by 1989 to 72 operations by 2017.7 Apart from promoting preventive diplomacy and distinguishing peacekeeping and peacemaking efforts, the Agenda for Peace was the first official UN effort to underscore the importance of peace consolidation or post-conflict peacebuilding.8 This constituted a significant advancement in the process of peacebuilding, given that many conflicts resurface soon after a peace agreement is reached.

Not coincidentally, research on peacebuilding also grew by leaps and bounds. Much in line with the then prevailing optimistic sentiment driven by the seemingly ultimate triumph of the liberal project over socialist designs for global order,9 mainstream thinking in peacebuilding built on what has subsequently become known as the “liberal peace project.” This sought to transform conflict societies by fostering security, institutional stability, good governance, rule of law, human rights protection, free elections, legitimate rule, and socioeconomic development into state entities resembling Western nations. Following Kantian logic, the causal relationship between democracy and peace was considered decisive in this transformation. Over time, post-conflict peacebuilding missions became more sophisticated and eventually moved away from one-size-fits-all blueprints. More emphasis was placed on sociopolitical contexts and local ownership (Bräuchler 2018: 21), and incorporating devolution and decentralization components into the projects’ toolbox. Yet most interventions still came from external actors, mainly international organizations and the economically advanced donor countries of the West, which regarded peacebuilding as part and parcel of their larger development agenda. The latter pursued the objective of modernizing backward societies, a process in which local agents played only a subordinate role at best (Schneckener 2016; Debiel & Rinck 2016).

However, the ambivalent results of the liberal peace project – including disastrous failures such as in Somalia, Rwanda, Iraq, and Libya – triggered a paradigm shift in peacebuilding research. So-called post-liberal approaches criticized the liberal project as a paternalistic, top-down, Eurocentric, teleological, and modernization theory-driven exercise. For them the mainstream liberal peace project had become a technocratic process of social engineering in which external agents imposed on non-Western societies liberal norms and concepts of a Western-dominated international order (Schneckener 2016: 3; Bräuchler 2018: 21). This agenda, they reasoned, was self-serving, as it sought to protect the West from unwanted spill-overs from peripheral conflict societies, including the destabilizing effects of state failure, terrorism, and irregular migration (Schneckener 2016: 5).

The liberal peace project, its critics argued, rested on “methodological nationalism” and blatantly ignored the complexities of conflict societies, cultural variation, and local agency (Debiel & Rinck 2016: 241). Post-liberal approaches and critical peace research thus shifted attention from international agency to local agency. If peacebuilding projects intend to avoid or at least reduce local resistance, local actors must be empowered and become key agents in the process of sustainable reconciliation (Paffenholz 2015: 859). Influential local actors include local politicians and administrators; traditional, clan, and religious leaders; NGO activists; teachers; businesspeople; and vigilante commanders (Debiel & Rinck 2016: 246). Bringing local actors back in also facilitates the rediscovery of customary laws and local culture with their pacifying effects in peacebuilding processes (Bräuchler 2009).

This “local turn” in peacebuilding research has also been criticized in recent years. At the center of objections is the tendency to romanticize “the local” by ignoring local power structures. Local conditions are frequently characterized by clientelist practices and elite capture. Peacebuilding measures often remain contested, not least because they are deeply embedded in local power struggles and conflicting interests. Some have thus rightly argued that “the local” is not, in and of itself, a “panacea of legitimacy” (Simons & Zanker 2014: 5). It is not “a homogeneous entity” and is only “as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ as society writ large” (Paffenholz 2015: 860).

However, despite these qualifications aired against the “local turn” and its derivative of “hybrid peacebuilding” – a response to the critique summarized above and an approach which seeks to combine and fuse external and local actorness in peacebuilding (Mac Ginty & Richmond 2013, 2014; Debiel & Rinck 2016) – it is undeniable that without due recognition of local agency, sustainable peace is illusory. By focusing on religious actors, the research project underlying this book concentrated on one particularly crucial group of local actors in post-conflict peacebuilding, one that is also frequently identified as a major source of armed conflict (Larousse 2001). We thus developed an analytical framework for our study that draws on the pioneering work of Lederach and, in particular, his emphasis on the “local turn” in contemporary peacebuilding efforts.

We follow Lederach’s conceptualization of peacebuilding as a two-dimensional process, which allows for the combination of structuralist, actor-centered and reflexivist perspectives. Slightly modifying his terminology, the first dimension is placed on the vertical axis and examines conflict evolution. The second dimension is located on the horizontal axis and analyzes peacebuilding activities (see Figure 2.1).

More specifically, the dimension of conflict evolution is primarily concerned with the identification of the conflict’s root causes, its scope conditions and historical trajectories. This entails a structural analysis, as we assume that the root causes are embedded in socioeconomic structures. Structural analysis in conflict research usually focuses on material issues such as economic deprivation, political discrimination, and major demographic changes caused, for instance, by processes of managed or spontaneous migration.

Yet more recent research has persuasively shown that marginalization and discrimination alone rarely trigger religious violence. In most cases, “conflicts start with words” (Tishkov 2004: 78). In order to erupt, religious violence requires the existence of elite agents who strongly believe that only armed struggle can overcome the predicament of their religious group. In order to persuade the majority of their followers that violent action is a rational choice (in which the perceived benefits exceed the anticipated costs, sacrifices, and sufferings), they must possess discursive skills. They must be able “to represent violence as the appropriate course of action in a given situation” (Schröder & Schmidt 2001: 5). They must, in other words, create narratives in which the “self,” that is, the “we-group,” is associated with righteousness, civilization, and courage, whereas the “religious other,” that is, “them,” is characterized by wickedness, barbarism, and malice (Jabri 1996: 108; Demmers 2015: 133). An integral strategy in this process is to memorize and interpret previous experiences with the other group selectively, thereby entrenching and exacerbating existing everyday social categorizations and stereotypes with the ultimate objective of justifying violence. Such narratives reproducing religious hostility gain further credibility through rumors, often conveyed by refugees who report abject atrocities perpetrated by the opponents, which eventually become a “social truth” (Demmers 2015: 135). The militancy of large parts of the population is likely to increase under such conditions and can translate into all-out civil war. In addition, militant group leaders seek to further solidify the “we-group” by stigmatizing those that oppose armed struggle as “traitors” to their community who need to be censured, sidelined, or even punished (Jabri 1996: 108; Demmers 2015: 113). If such attitudes harden and become a habitus – as theorized by Bourdieu (1982) – peace initiatives are hindered.

While, in a nutshell, relational discursive representations serve the recruitment of supporters by propagating a concrete us/them divide, and the legitimation of violent action (Schröder & Schmidt 2001: 5–8; Demmers 2015: 137), it should not be overlooked that discursive processes may also facilitate peacebuilding efforts. War fatigue may be expressed in narratives that highlight the sacrifices in human life, the sufferings of the people, and the material losses caused by the conflict. It can serve as a means of expressing the belief that violence will yield no winners and that it is primarily external actors who instigate armed conflict and benefit from its prolonged presence.

The second dimension, peacebuilding activities, places emphasis on the process of conflict management and conflict transformation. Here we follow Lederach (1997), who distinguishes between “conflict resolution” or “conflict management” and “conflict transformation” (Lederach 1997: 80). The former includes a number of activities in which the participation of conflict parties varies and which eventually end hostilities. According to Assefa, this can include peace through the use of force, that is, military victory, adjudication, arbitration, negotiation, and mediation (Assefa 2015: 237). Such interventions facilitate what Galtung has termed “negative peace” or, in other words, the absence of manifest violence (Galtung 1990).

While for Lederach “conflict resolution” or “conflict management” ends an unwanted situation by achieving a modicum of agreement between the conflict parties, “conflict transformation” is a much more demanding and complex endeavor. It aims to create a desired situation, requiring change along personal, relational, structural, and cultural dimensions (Lederach 1997: 82). Its long-term goal is conflict prevention, in other words a situation in which war and armed conflict are no longer an option. This development of human potential is what Galtung conceptualized as “positive peace” (Galtung 1990), what for Assefa denotes “reconciliation” (Assefa 2015: 240) and what for Senghaas is a civilizational project implying the realization of a “civilizational hexagon” (Senghaas 1998; see also Neumann 2009: 31).10

Figure 2.1 Framework of analysis

Source: Adapted from Lederach (1997: 80).

Reconciliation marks a process in which not only are the underlying issues in the conflict resolved to the satisfaction of broad segments of the population, but the antagonistic attitudes and relationships between the adversaries are also increasingly transformed from negative into positive sentiments. More than that, it also entails a concern for “restorative justice,” which Braithwaite defined as “a process where all stakeholders affected by an injustice have an opportunity to discuss how they have been affected by the injustice and to decide what should be done to repair the harm” (Braithwaite 2004: 28). Reconciliation may thus be described as a long-term effort of one to two decades (Lederach 2015) to “rebuild a more livable, and psychologically healthy environment between former enemies where the vicious cycle of hate, deep suspicion, resentment, and revenge does not continue to fester” (Assefa 2015: 241). A transformation and reconciliation process that transcends a mere coexistence of erstwhile hostile groups (Duncan 2013: 106, 120; Mac Ginty 2014: 557), or what Mac Ginty called a state of “everyday peace” (Mac Ginty 2014: 557) that is characterized by a “tolerance of prejudice” (Harris 1972: 200), invariably requires the inclusion and participation of grassroots actors. Peacebuilding activities benefit from a process in which key actors – facilitated by peace education – respect, promote, and actively draw from the human and cultural resources of local communities (Lederach 1997). We will scrutinize in the empirical part below how and in what way this inclusionary and community-grounded approach pursued by religious actors had a pacifying effect on the conflicts in Mindanao and Ambon.

This brief review of the literature highlights a number of themes and aspects that are pivotal to our study of local peacebuilding efforts in Indonesia and the Philippines. One aspect that stands out is the realization that successful peacebuilding efforts are highly contingent on national and local contexts and actors. Consistent with the arguments of the “local turn” literature, we contend that a deeper understanding of local powers, interests, and ideas is a key asset for assessing Southeast Asian experiences of conflict and reconciliation. Moreover, this section has demonstrated that the peacebuilding process is often uneven and incremental, not least because it is shaped by the complex interplay of religious ideas, local grievances, and materialist interests. Against this backdrop, progress is more likely to ensue if contending groups move beyond existing and established sentiments and jointly create a new common ground – a “third culture” (Broome 2004). This also tallies well with Lederach’s (2003) notion of “relationship-centered solutions” that entail shared visions and intensive dialogues.

1 See Galtung (1990), Lederach (1997, 2003, 2015), Mac Ginty (2008, 2011, 2014); Mac Ginty and Richmond (2007); Paris (2004); Richmond (2005).

2 Violent conflicts are usually equated with armed engagements, which according to a widely accepted definition by the University of Uppsala can be summarized as follows: “A contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least twenty-five battle-related deaths in one calendar year.” See University of Uppsala, www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/ (accessed 12 April 2014). The Uppsala researchers speak of a war if the death toll exceeds 1,000 combat-related deaths per year (Collier & Höffler 2004: 565).

3 In the case of the Philippines and Indonesia, conflict parties are often well aware that such ideology-driven conflicts can be very resilient to efforts of reconciliation. For Mohagher Iqbal, the chief peace negotiator of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), some form of compromise or negotiated solution is possible “as long as the issue in contention is not purely religious or ideological” (Jubair 2007: 18).

4 For a cogent summary of intra-faith conflicts see, for instance, Ramsbotham, Woodhouse and Miall (2016: 400) and El Fadl (2006).

5 Comment in an interview by Ateneo de Manila University anthropologist, Father Albert Alejo, 10 September 2015.

6 Kompas, 7 September 2001.

7 A compilation of all UN missions since 1956 is available at: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/past-peacekeeping-operations (accessed 24 December 2017).

8 The United Nations Agenda for Peace, available at: www.un-documents.net/a47-277.htm (accessed 24 December 2017).

9 See, for instance, President George HW Bush’s “New World Order” speech, and in the academic realm Fukuyama (1992).

10 The “civilizational hexagon” consisted of the state monopoly of coercion, interdependence, control of emotions, social justice, a culture of conflict resolution, democratic principles, and rule of law. See Senghaas (1998).

Al Qurtuby, Sumanto (2015): “Christianity and Militancy in Eastern Indonesia: Revisiting the Maluku Violence,” Southeast Asian Studies 4(2): 313–339.

Al Qurtuby, Sumanto (2016): Religious Violence and Conciliation in Indonesia: Christians and Muslims in the Moluccas, London & New York: Routledge.

Assefa, Hizkias (2015): “The Meaning of Reconciliation,” In: Tom Woodhouse, Hugh Miall, Oliver Ramsbotham & Christopher Mitchell (eds.), The Contemporary Conflict Resolution Reader, Malden, MA: Polity Press, pp. 236–243.

Böhm, Cees J. (2006): Brief Chronicle of the Unrest in the Moluccas 1999–2006, Ambon City: Crisis Centre Diocese of Amboina.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1982): Die feinen Unterschiede: Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Braithwaite, John (2004): “Restorative Justice and De-Professionalization,” The Good Society 13(1): 28–31.

Bräuchler, Birgit (2009): “Mobilizing Culture and Tradition for Peace: Reconciliation in the Moluccas,” In: Birgit Bräuchler (ed.), Reconciling Indonesia: Grassroots Agency for Peace, Oxon & New York: Routledge, pp. 97–118.

Bräuchler, Birgit (2018): “The Cultural Turn in Peace Research: Prospects and Challenges,” Peacebuilding 6(1): 17–33.

Broome, Benjamin J. (2004): “Reaching Across the Dividing Line: Building a Collective Vision for Peace in Cyprus,” Journal of Peace Research 41(2): 191–209.

Collier, Paul & Höffler, Anke (2004): “Greed and Grievance in Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 56: 563–595.

D’Ambra, Sebastiano (2011): “The Mindanao Conflict and the Silsilah Dialogue Movement,” In: Thomas Schreijäck (ed.), Prekäres Christsein in Asien: Erfahrungen und Optionen einer Minderheitenreligion in multireligiösen Kontexten, Ostfildern: Matthias Grünewald Verlag, pp. 77–99.

Debiel, Tobias & Rinck, Patricia (2016): “Rethinking the Local in Peacebuilding. Moving Away from the Liberal/Postliberal Divide,” In: Tobias Debiel, Thomas Held & Ulrich Schneckener (eds.), Peacebuilding in Crisis: Rethinking Paradigms and Practices of Transnational Cooperation, Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 240–256.

Demmers, Jolle (2015): “Telling Each Other Apart: A Discursive Approach to Violent Conflict,” In: Tom Woodhouse, Hugh Miall, Oliver Ramsbotham & Christopher Mitchell (eds.), The Contemporary Conflict Resolution Reader, Malden, MA: Polity Press, pp. 132–140.

Duncan, Christopher R. (2005): “The Other Maluku: Chronologies of Conflict in North Maluku,” Indonesia 80: 53–80.

Duncan, Christopher R. (2013): Violence and Vengeance: Religious Conflict and Its Aftermath in Eastern Indonesia, Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

Efinger, Manfred, Rittberger, Volker & Zürn, Michael (1988): Internationale Regime in den Ost-West-Beziehungen, Frankfurt am Main: Haag & Herchen.

El Fadl, Khaled A. (2006): Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, Donald G. (2006): Group Conflict: Transforming Conflict: Communication and Ethnopolitical Conflict, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Fearon, James & Laitin, David D. (2015): “Ethnicity, Insurgency and Civil War,” In: Tom Woodhouse, Hugh Miall, Oliver Ramsbotham & Christopher Mitchell (eds.), The Contemporary Conflict Resolution Reader, Malden, MA: Polity Press, pp. 141–143.

Fukuyama, Francis (1992): The End of History and the Last Man, New York & Toronto: The Free Press.

Galtung, Johan (1990): “Cultural Violence,” Journal of Peace Research 27(3): 291–305.

Gupta, Sanjeev, Clements, Benedict, Bhattacharya, Rina & Chakravarti, Shamit (2002): “The Elusive Peace Dividend,” Finance and Development 39(4), available at: www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2002/12/gupta.htm (accessed 15 March 2018).

Harris, Rosemary (1972): Prejudice and Toleration in Ulster: A Study of Neighbours and “Strangers” in a Border Community, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hechter, Michael (1975): Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1536–1966, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hehanussa, Jozef M.N. (2013): Der Molukkenkonflikt von 1999: Zur Rolle der Protestantischen Kirche (GPM) in der Gesellschaft, Münster: LIT Verlag.

International Alert (2014): Rebellion, Political Violence and Shadow Crimes in the Bangsamoro: The Bangsamoro Conflict Monitoring System (BCMS), 2011–2013, London: International Alert.

Jabri, Vivienne (1996): Discourses on Violence: Conflict Analysis Reconsidered, Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press.

Jubair, Salah (2007): The Long Road to Peace: Inside the GRP-MILF Peace Process, Cotabato City: Institute of Bangsamoro Studies.

Kreuzer, Peter & Weiberg, Mirjam (2007): Zwischen Bürgerkrieg und friedlicher Koexistenz: Interethnische Konfliktbearbeitung in den Philippinen, Sri Lanka und Malaysia, Bielefeld: Transcript.

Larousse, William (2001): A Local Church Living for Dialogue: Muslim-Christian Relations in Mindanao-Sulu (Philippines) 1965–2000, Rome: Editrice Pontificia Universita Gregoriana.

Lederach, John Paul (1997): Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Lederach, John Paul (2003): The Little Book of Conflict Transformation, Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Lederach, John Paul (2015): “Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies,” In: Tom Woodhouse, Hugh Miall, Oliver Ramsbotham & Christopher Mitchell (eds.), The Contemporary Conflict Resolution Reader, Malden, MA: Polity Press, pp. 120–124.

Mac Ginty, Roger (2008): “Indigenous Peacemaking Versus the Liberal Peace,” Opposition and Conflict 43(2): 139–163.

Mac Ginty, Roger (2011): International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance: Hybrid Forms of Peace, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mac Ginty, Roger (2014): “Everyday Peace: Bottom-Up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies,” Security Dialogue 45(6): 548–564.

Mac Ginty, Roger & Richmond, Oliver (2007): “Myth or Reality: Opposing Views on the Liberal Peace and Post-War Reconstruction,” Global Society 21(4): 491–497.

Mac Ginty, Roger & Richmond, Oliver (2013): “The Local Turn in Peace Building: a critical agenda for peace,” Third World Quarterly 34(5): 763–783.

Miller, Christopher Allan (2005): A Glossary of Terms and Concepts in Peace and Conflict Studies, Geneva: University for Peace.

Neumann, Hannah (2009): Friedenskommunikation: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen von Kommunikation in Konfliktransformation, Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Paffenholz, Thania (2015): “Unpacking the Local Turn in Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment Towards an Agenda for Future Research,” Third World Quarterly 36(5): 857–874.

Panggabean, Samsu Rizal (2004): “Maluku: The Challenge of Peace,” In: Annelies Heijmans, Nicola Simmonds & Hans van de Veen (eds.), Searching for Peace in Asia Pacific: An Overview of Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding Activities, Boulder & London: Lynne Rienner, pp. 416–437.

Paris, Roland (2004): At War’s End: Building Peace After Civil Conflict, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramsbotham, Oliver; Woodhouse, Tom & Miall, Hugh (2016): Contemporary Conflict Resolution, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Richmond, Oliver (2005): The Transformation of Peace, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schneckener, Ulrich (2016): “Peacebuilding in Crisis? Debating Peacebuilding Paradigms and Practices,” In: Tobias Debiel, Thomas Held & Ulrich Schneckener (eds.), Peacebuilding in Crisis: Rethinking Paradigms and Practices of Transnational Cooperation, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 1–20.

Schröder, Ingo W. & Schmidt, Bettina (2001): “Introduction: Violent Imaginaries and Violent Practices,” In: Bettina Schmidt & Ingo W. Schröder (eds.), Anthropology of Violence and Conflict, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 1–24.

Senghaas, Dieter (1998): Zivilisierung wider Willen, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Silvestri, Sara & Mayall, James (2015): The Role of Religion in Conflict and Peacebuilding, London: The British Academy.

Simons, Claudia & Zanker, Franzisca (2014): “Questioning the Local in Peacebuilding,” Working Papers of the Priority Programme 1448 of the German Research Foundation, Nr. 10.

Spyer, Patricia (2002): “Fire Without Smoke and Other Phantoms of Ambon’s Violence: Media Effects, Agency, and the Work of Imagination,” Indonesia 74: 21–36.

Tambiah, Stanley J. (1991): Sri Lanka: Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy, Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Tambiah, Stanley J. (1996): Leveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South Asia, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tishkov, Valery A. (2004): “Conflicts Start with Words: Fighting Categories in the Chechen Conflict,” In: Andreas Wimmer, Richard J. Goldstone, Donald L. Horowitz, Ulrike Joras, Conrad Schetter (eds.), Facing Ethnic Conflicts: Toward a New Realism, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 78–95.