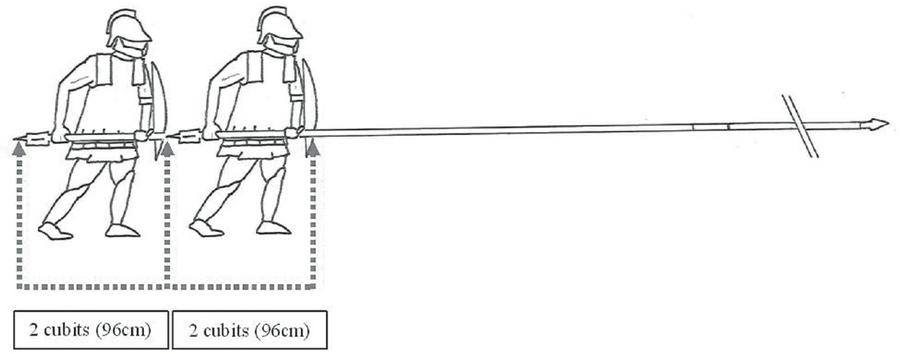

The sarissa was one of the tools that helped create the Hellenistic world. The employment of massed formations of men wielding this weapon allowed the Macedonians to subjugate (and then tenuously unite) most of Greece, and then conquer, and subsequently fight over, an empire that stretched from the Aegean to Egypt and India. Consequently, any understanding of the warfare of the Hellenistic Age must include a thorough examination of this influential piece of weaponry.

Unfortunately, this is no easy task due to two separate, yet inter-related, problems. The first of these problems is that the design of this weapon changed during the time of the sarissa’s common usage. The length of the sarissa was altered across the Hellenistic Period as army after army sought to gain an advantage over those employing similar methods and weaponry. Additionally, some of the passages which describe certain aspects of the sarissa were written at a time after it was no longer used and so cannot be describing a contemporary weapon. As a consequence, the exact configuration of the sarissa has become a matter of controversy for scholars who have argued over different characteristics for the weapon and how the ancient writers described it. However, a critical examination of the available evidence not only allows for the developmental sequence of the sarissa across the Hellenistic Period to be established, it also allows for the specifications of the weapon’s constituent parts to be identified as well. This, in turn, allows for the scholarly debate on the subject to be addressed and many of the problematic ancient passages relating to the weapons and tactics of Hellenistic warfare to be seen in their correct context.

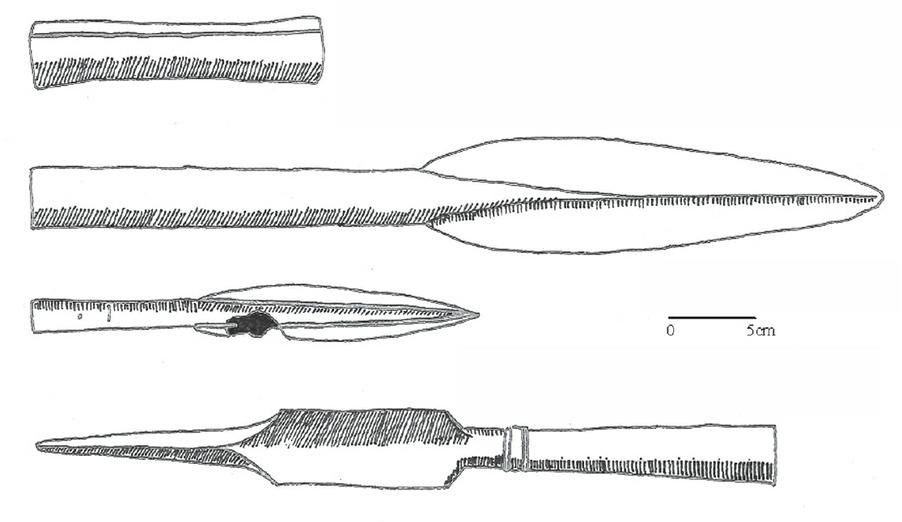

Fig. 1: Line drawings of (top to bottom) the ‘connecting tube’ large ‘head’, small ‘head’, and butt found at Vergina by Andronicos.¹

However, one of the main problems in determining the correct characteristics of the different constituent parts of the sarissa is the rather limited amount of available evidence. Like the earlier spear of the classical hoplite (doru) it appears that the sarissa was equipped with both a leaf shaped iron head on the forward tip of the shaft and a large heavy metallic spike (the sauroter of the hoplite spear) on the rearward end. Unlike the earlier hoplite spear, however, there is a distinct lack of examples of these metallic sarissa components that have survived within the archaeological record. As with many aspects of Hellenistic warfare, this dearth of clearly identifiable source material has led to much contention between scholars over the size of the different parts and the configuration of the sarissa. However, due to the interwoven nature of how the design of a weapon affects its performance, the various theories that have been forwarded regarding the characteristics of the sarissa affect subsequent models of Hellenistic warfare upon which they are based. This, in turn, has led to a vast number of interpretations of the mechanics of Hellenistic combat. However, by correlating the limited archaeological evidence with ancient descriptions and images of the sarissa, and then comparing this information to the physical properties of an assembled sarissa, a comprehensive outline of the configuration of the weapon as a whole, and broken into its constituent parts, can be compiled.

In 1970, Andronicos found what appears to be the butt-spike of a sarissa, along with pieces of various other weapons, outside of a tumulus grave at Vergina in Macedonia (Fig. 1).

The finds were thought to have been items discarded by grave robbers who apparently viewed them as possessing no intrinsic value.² The butt that was found was described as:

An iron spike. It is composed of three parts…the socket – the body, in the form of four wings – the point, with a pyramidal form…Total length: 445mm. Length of the socket: 180mm. Length of the point: 145mm. Maximum width (at wings): 40mm. Diameter of socket: 34mm. Thickness [of socket]: 2-2.5mm. Weight: 1,070g.³

Andronicos concluded that the butt had come from a Macedonian sarissa and dated the find to the late fourth century BC (c.340-320BC).⁴

The butt of the sarissa is rarely shown in Hellenistic art with such a configuration as the one found by Andronicos. In fact, there are no depictions of the sarissa at all which clearly distinguish the shape and size of all of the different parts of the weapon. Tomb paintings such as those found at Boscorale or Vergina regularly contain an individual holding a long shafted weapon of some kind which, unfortunately, extends beyond the margins of the mural in most cases, or is obscured by other features of the image. Consequently the exact size of the weapon being shown cannot be gauged and it is uncertain whether the weapon in such paintings is a spear or a sarissa. The paintings at both Boscorale and Vergina show weapons with butts more akin to the sauroter of the spear of the Classical hoplite than of weapons equipped with the butt found by Andronicos, but this is no indication of exactly which type of weapon they are.

Another butt-spike, now in the Shafton Collection in the Great North Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne (#111), is significantly different from the butt found at Vergina by Andronicos and is, in shape, closer to the sauroter of the hoplite spear. It has been suggested that the spike dates to the late fourth century BC – although dating it with any certainty is all but impossible (Plate 2).⁵

The distinctive wings of the Vergina find are absent from the Newcastle spike which is, similar to some versions of the hoplite sauroter, merely a tubular socket flaring out into an elongated spike – in this case conical in shape. What definitively identifies this spike as coming from a Macedonian weapon, rather than the spear of a Greek hoplite, are the painted letters MAK (for ‘Makedonian’) on the socket. Sekunda suggests that this is an indication of the weapon (or at least the butt-spike) being state issued equipment to the Macedonian military.⁶ It may be representations of this style of butt-spike that feature more regularly in Hellenistic era tomb paintings.

The length of the Newcastle spike (380mm) is somewhat shorter than the butt found by Andronicos, but is larger than the average length of the sauroter that was affixed to the hoplite spear (which had an average length of 259mm).⁷ The weight of the Newcastle spike (876g) is also less than that of the Vergina butt but, again, is distinctly greater than the average weight of the hoplite sauroter (329g). The weight of both the Vergina find and the Newcastle spike indicate that they have come from a weapon considerably heavier than a traditional hoplite spear. This suggests that they have both come from a sarissa. Additionally, the diameter of the socket of the Newcastle spike (33.5mm) is almost exactly the same as the diameter of the Vergina spike; both of which are larger than the average diameter of the socket of the hoplite sauroter (25mm). Even in the late Classical/early Hellenistic period when the Greeks more commonly used iron to make the sauroter, the average weight only increased to 545g while the diameter of the socket remained almost unchanged. This all but confirms that both the Newcastle spike and the Vergina find have come from a weapon with a shaft of a greater diameter than the average hoplite spear – most likely a sarissa. Traces of pitch inside the socket of the Newcastle spike indicates that it was fixed in place via the use of an adhesive rather than by having it riveted to the shaft. The absence of any hole from the use of rivets to secure it in place also indicates that the butt found at Vergina had to have been attached to the shaft of the weapon to which it belonged through the use of some form of adhesive.

Despite the lack of direct confirmatory evidence, Andronicos’ find is generally assumed to be the butt of a sarissa. Everson claims that the Newcastle butt belongs to a Hellenistic cavalry lance rather than a pike.⁸ Sekunda, on the other hand, attributes it to the sarissa.⁹ If the dating of the Newcastle spike is correct, then it has clearly come from an infantry weapon as the butt of the Hellenistic cavalry lance during this time had a different configuration (see following).

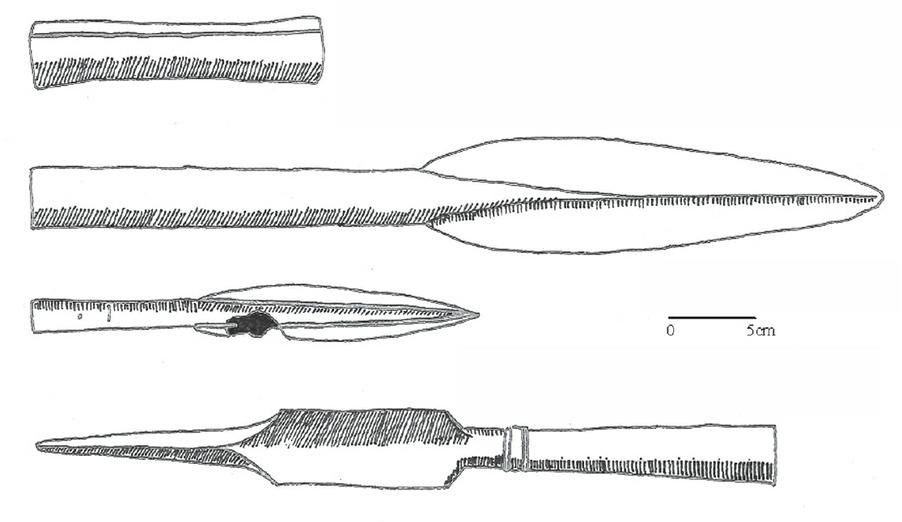

Thus, like the sauroter of the hoplite spear, it appears that the spike on the rearward end of the sarissa could come in a variety of shapes with the only thing in common being the diameter of the socket (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of the Newcastle spike, the Vergina find and the average hoplite sauroter.¹⁰

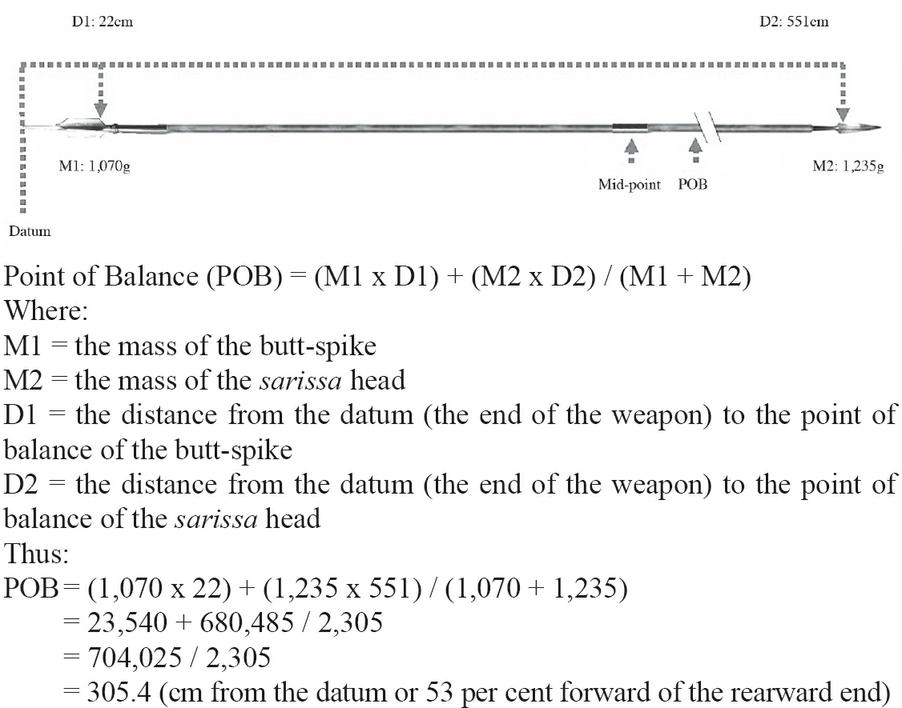

Sekunda offers that it is uncertain whether the sarissa possessed a butt-spike or not.¹¹ However, what conclusively proves that it did is the fact that, without one, the sarissa could not be configured in a way that then correlates with the descriptions of this weapon that are found in the ancient texts. In other words, it was not the shape of the butt that was important to the functionality of the weapon it was attached to, but rather its weight as, when affixed to a shaft with a head at the opposite end, any difference in weight between the head and the butt would significantly influence the location of the weapon’s point of balance, the performance of the weapon, and subsequently where it could be held in order to be used effectively in battle (see following).

Another important aspect of the butt-spike was its length. Both the Newcastle spike and the Vergina find are both smaller than 1 cubit (48cm in the Hellensitic Period) in size. This was important as a butt-spike could not be of a larger size without imposing on the ability of the person carrying it, and those around him, to conform to the intervals of the densely packed formation of the phalanx (see Bearing the Phalangite Panoply from page 133). The weights, lengths and socket diameters ofboth the Newcastle spike and the find from Veigina set them apart from the hoplite sauroter and indicate that they have come from two different weapons but with very similar configurations in terms of the size of their shaft. Again, these weapons are most likely the sarissa. Taking these two examples as the basis, the iron butt that was affixed to the rear end of the sarissa would have averaged 413mm in length, came in a variety of shapes, was attached to the shaft via a tubular socket with an inner diameter of 30mm, and had an average weight of around 973g.

Outside of the tumulus grave at Vergina, Andronicos also recovered two items which he labelled as ‘lance heads’ (Fig. 1):

| a) | The point of a lance in iron…Total length: 51cm. Length of the socket: 23.5cm. Maximum width of the head: 6.7cm. Diameter of the socket: 3.6cm. Thickness of the wall of the socket: 2-3mm. Weight: 1,235g.¹² |

| b) | The point of a lance in iron…Total length: 27.3cm. Length of the socket: 8.0cm. Maximum width of the head: 3.0cm. Diameter of the socket: 1.9cm. Thickness of the wall of the socket: 1-1.5mm. Weight: 97g.¹³ |

Andronicos claimed that the larger of the two ‘heads’ and the butt-spike recovered from the same site had come from the same weapon: a Macedonian sarissa. Andronicos reached this conclusion as the diameter of the socket for both of these items were of a similar size (34mm for the butt and 36mm for the head) and because there were many similarities in the metal used to make the two items.¹⁴ Numerous scholars have accepted Andronicos’ interpretation of the artefacts and have subsequently used a weapon configured with this large head in their own examinations of the sarissa and of Hellenistic warfare.¹⁵

Markle, for example, echoes Andronicos by stating that the larger of the two heads had come from a sarissa while he further suggests that the smaller had come from a regular hoplite spear.¹⁶ Markle then uses this conclusion as the basis for identifying the different types of heads found elsewhere stating: ‘a sufficient number of sarissa heads has been found to demonstrate that they can easily be distinguished from the traditional hoplite spear head’ and that ‘the striking difference is in their respective weights’.¹⁷

For example, a head found at Vergina by Petsas, which had an overall length of 55 cm, was identified by Markle as another example of the head of a sarissa due to the similarities in size between it and the one found by Andronicos.¹⁸ Using this conclusion as the basis, Markle then dismisses many interpretations of other finds. He states that not one example of the sarissa head can be identified from those recovered from excavations at Olynthus and that the ones identified as such by Robinson are too small to have come from the sarissa.¹⁹ Markle continues, stating that the largest head found at Olynthus, which measured 29cm in length, would be more suited to a hoplite spear.²⁰ Another head found by Petsas, with a length of 34cm, was said to be too small for a sarissa by Markle, but too big for a hoplite spear.²¹ Unfortunately, Markle did not elaborate on what weapon he thought the head had come from. Other heads found with lengths of 27cm and 31cm were interpreted by Markle as clearly coming from the hoplite spear.²² Confusingly, the best preserved head found in the Macedonian polyandrion at Chaeronea measures 31cm.²³ Markle states that this is from a sarissa, but does not state why he believes that other heads of a similar size found elsewhere are not.²⁴ Champion similarly states that no sarissa heads have been found at Olynthus, but have been found at Chaeronea.²⁵

Markle also published data on two more heads found at Vergina – one measuring 470mm and with a weight of 235g, and the other measuring 500mm with a weight of 297g.²⁶ Both of these finds were made from two halves hammer-welded together which made them much lighter than their respective sizes would suggest.²⁷ Connolly suggests that the smaller of the two appears closest to the type of head depicted in the representations of the sarissa in the Alexander Mosaic now in the Naples Museum (see Plate 5).²⁸

There are numerous problems associated with such approaches to identifying the head of the sarissa. Firstly, the head of the Greek spear, whether that of the hoplite, the javelin or of the hunting spear, came in a variety of styles and sizes across the period of their common usage. Snodgrass, in his examination of Greek armour and weapons, classified Greek spearheads into fourteen different categories based upon their size, shape, the material they were constructed from and their period of use.²⁹ Among these classifications, Snodgrass refers to the ‘J style’ spearhead as the ‘hoplite spear par excellence’.³⁰ The ‘J style’ spearhead is typified by its long socket, its long, narrow, blade, and its sloping shoulders. This type of spearhead saw service in warfare from the late geometric period (c.700BC) onwards.³¹ The average dimensions of the ‘J style’ hoplite spear head are a length of 27.9cm, a width of 3.1cm, a socket with a diameter of 1.9cm and a total weight of 153g.³² Despite being the ‘hoplite spear par excellence’ as Snodgrass describes it, the ‘J style’ is not the most common type found in the archaeological record – this is a distinction belonging to the smaller ‘M style’ which had a period of use from the early Protogeometric Age (c.1,000BC) to the fall of the Roman Republic (c.31BC). Thus even the more archaeologically common head of the hoplite spear, let alone that of the sarissa, cannot be easily distinguished by size alone. The identification of the sarissa head can only be made via comparison and correlation with other sources of evidence.

This is where Markle’s conclusions encounter further problems. In his treatise On Hunting, the ancient writer Grattius outlines the unsuitability of the sarissa for such a pursuit due to its ‘small teeth’.³³ This suggests that the sarissa was tipped with a head recognisably smaller than the large heads of regular hunting spears. This in itself would discount any correlation with the large head found by Andronicos and the head of the sarissa. Furthermore, the large ‘head’ as it was identified by Andronicos appears to actually be the butt of a Macedonian cavalry lance rather than the head of an infantry weapon.³⁴ Hammond notes that cavalrymen in the time of Philip II carried a lance with ‘a blade at either end’.³⁵ This rearward ‘blade’ seems to have been larger than the forward tip of the lance – most likely to provide the weapon with a particular point of balance. A wall painting from ‘Kinch’s Tomb’ at Lefkadia (c.310-290BC) clearly shows the rearward end of the cavalry lance equipped with a large secondary ‘head’ just like the one found at Vergina (Plate 3).

The depiction of Alexander the Great on the famous mosaic from Pompeii (#10020 in the Naples Museum) shows the rear end of the lance wielded by the young king. The detail of the rear end of this weapon, which is unfortunately fragmented and mostly missing, also seems to be tipped with a large, blade-like butt similar to that depicted in Kinch’s Tomb (Plate 4).³⁶

The image in the mosaic is thought to be a copy of a painting by Philoxenos of Eretria from the fourth century BC – possibly commissioned by Cassander after he had become ruler of Macedonia in 317BC.³⁷ Thus the image of the weapon carried by Alexander, although second-hand through the reproduction in the mosaic, is a contemporaneous depiction of a weapon used at the time, and the slightly later depiction of a similar weapon in Kinch’s Tomb would suggest a fairly common usage of a cavalry lance with a large, blade-like, butt.³⁸

Additionally, the Alexander mosaic also contains several representations of the sarissa. None of these possess an overly large head (see Plate 5). Nylander, who accepts the large ‘head’ found at Vergina as the head of a sarissa, states that ‘it is interesting to note that the artist [who made the Alexander mosaic] never hints at such a conspicuous point on any of the lances depicted…’³⁹ Nylander’s conundrum is easily explained. The reason why large heads are not depicted on the weapons shown in the Alexander mosaic is becuase the sarissa was not equipped with a large head like the one recovered from Vergina – just as Grattius states.

If the large ‘head’ recovered by Andronicos is indeed the butt from a cavalry lance as the pictorial evidence suggests, this not only makes Markle’s considerations, and those similarly based upon Andronicos’ conclusion, void, but also opens the question as to what size the head of the sarissa actually was. Some scholars, dismissing the large ‘head’ found by Andronicos (and of Markle’s hypotheses), base their examinations of the configuration of the sarissa using the smaller ‘head’ that was discovered.⁴⁰ Connolly, for example, discounted the idea that the smaller head found at Vergina was that of a javelin without providing any particular reason for this conclusion.⁴¹ However, all of the evidence points to this being the case.

The Greek javelin was equipped with a small leaf-shaped iron head and a small ‘butt-cap’ called a styrakion (στυράκιον).⁴² The average weight of the styrakion was only 90g and had an average diameter of 1.9cm for its socket. At Vergina a styrakion measuring 6.3cm was recovered from Tumulus LXVIII Grave E along with a head (27.5cm, 97g) from the same weapon.⁴³ This was evidenced by traces of the wooden shaft that remained between the two items. A head that is only marginally heavier than the butt gave the Greek javelin a point of balance slightly forward of centre – the optimum place to grip a shafted missile weapon. The similarity between this clearly identifiable javelin head and the smaller one found by Andronicos, in terms of weight, length and socket size, clearly distinguish them as coming from the same type of weapon. Thus it seems that the smaller head found by Andronicos is that of a javelin and has not come from either a sarissa or a hoplite spear. What this means is that, while the butt of a sarissa was found, the head was regrettably absent from Andronicos’ finds. This may be in part due to the motives that Andronicos assigned to them being discarded outside a tomb – a lack of immediate value for the tomb robbers who seem to have only taken the heads of the sarissa and cavalry lance found in the tomb while leaving the small head of the javelin, and the butts of the lance and sarissa, behind.

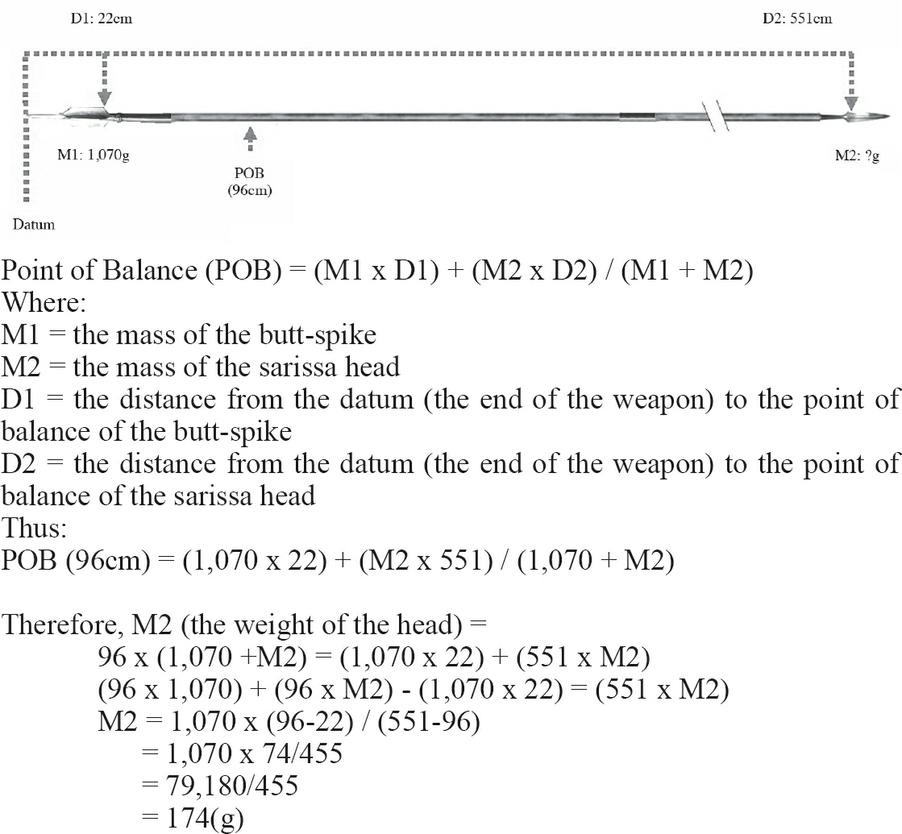

However, a lack of a clearly identifiable head for the sarissa within the archaeological record does not mean that examples of such items do not exist. The specifications of the head of the sarissa can be identified by other methods – in particular how the weight of the head affects the overall balance of the weapon (which is something that there is literary evidence for). Once the required characteristics of the sarissa head have been determined in this manner, this then allows for the possibility of whether any of the heads that have been recovered from Vergina, Olynthus and elsewhere, but which may have been dismissed as being sarissa heads by previous scholars, have possibly come from a sarissa or not (see the following section on The Balance of the Sarissa).

The other item recovered from Vergina by Andronicos, along with the butt of the sarissa and the two ‘heads’, was a small, cylindrical, metal tube (Fig. 1):

A socket in iron…with a concave profile…circular cross-section in the interior and polygonal on the exterior…length 17.0cm; Diameter 28mm (end ‘a’), 32mm (end ‘b’); Thickness: 2-3mm (end ‘a’), 3-5mm (end ‘b’).⁴⁴

The exact purpose of this item has caused considerable debate among scholars. Some scholars see the tube as the connector for a sarissa which came in two parts.⁴⁵ Others see the tube as something else. Dickinson states that whether the shaft of the sarissa is considered to have been a single piece of wood or two rests solely upon the interpretation of this iron tube and that the literary and archaeological sources are inadequate to resolve this issue.⁴⁶ However, by examining the physical properties of an assembled sarissa, the purpose of this item can be identified.

Those scholars who see the tube as a connector envisage a sarissa in which a forward section has the head attached, and a rearward section the butt, which could then be joined together through the use of the connecting tube to create a whole weapon.⁴⁷ A pike with such a configuration would certainly have its advantages in terms of logistics and operational adaptability. From a logistical perspective alone, being able to break a lengthy weapon down into two separate parts, possibly of the same length if it is assumed that the connecting tube was located in the middle, would make it much easier for the individual to carry.⁴⁸ Throughout his campaign, the troops under the command of Alexander the Great traversed all sorts of terrain including areas that were heavily wooded, steep and even covered in rainforest.⁴⁹ It seems almost incomprehensible that thousands of men could manoeuvre through such environments while carrying a pike over 5m in length without it becoming entangled in the foliage. Similarly, at Maleventum in 275BC, Pyrrhus led part of his army on a difficult night march, up the slopes of a heavily wooded hillside and along an overgrown goat track, in an attempt to outflank a Roman position.⁵⁰ The possibility of his men accomplishing such a feat while carrying pikes which, at this time, may have been over 7m in length is simply unthinkable.

Markle, in his argument for the sarissa only being used after 331BC, suggests that the account of the men of Perdiccas’ contingent of phalangites marching across steep forested terrain for an attack on the rear of the Persian Gates in 330BC is indicative that they were not carrying lengthy weapons. Markle concludes that the Macedonians had to be carrying two different weapons – the longer sarissa for set-piece battles, and shorter spears for moving over rough and wooded country.⁵¹ Similarly, English suggests that it would be difficult for troops to ferry lengthy weapons across rivers on makeshift rafts as Alexander had used to cross the Danube in 335BC (Arrian 1.3.5).⁵² However, what Markle and English have not considered is that these men may have been carrying pikes that had been separated into two sections – both of which would be about the same size as a traditional hoplite spear – and therefore much easier to transport. Additionally, having the sarissa come in two different sections would also make repairing any damaged part easier as smaller lengths of timber could be used to replace broken shafts more easily than if the weapon came only in one piece.

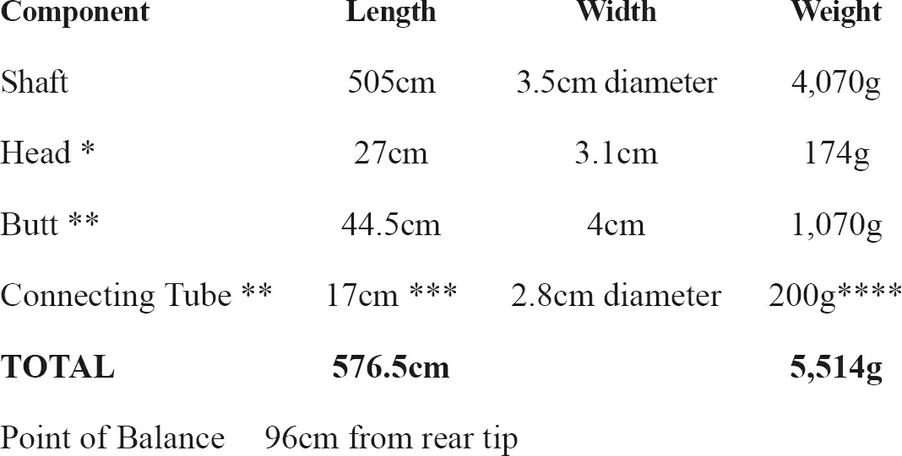

It may be the case that, if the tube was used to join the two halves of a sarissa together, it was permanently affixed to the forward part of the weapon in order to create a shorter weapon that could be used on its own in a manner similar to the hoplite spear or javelin. Due to the difference in the weight between the head of the hoplite spear (153g) and its large metallic butt-spike (329g), the hoplite spear had a point of balance approximately 89cm from its rearward tip.⁵³ No weight for the tube found at Vergina is given by Andronicos. However, a replica of it weighs 200g. If this is attached to one end of a shaft 244cm in length, and a head 27cm in length and 174g in weight is attached to the other, creating a weapon 288cm, or half of a 12 cubit sarissa, in length, the resultant weapon would have a point of balance 132cm from its rearward tip or a little less than half-way up the shaft.⁵⁴ This point of balance would allow the weapon to be used as a thrusting spear to some degree, but its balance would also allow it to be thrown like ajavelin as a more rearward point of balance makes flight almost impossible.⁵⁵ Thus the connecting tube would act as an improvised styrakion to provide a particular point of balance to the weapon.

Javelins seem to have been a fairly traditional Macedonian weapon. According to Arrian, Philotas was executed with a volley of javelins in 330BC (Φιλώταν μὲν κατακοντισθῆvαι).⁵⁶ Curtius states that Philotas was killed with lances (lanceis) – by which he seems to mean javelins.⁵⁷ Curtius later describes how the Macedonian Horratas (called Coragus by Diodorus (17.100.2)) armed himself with ‘regular’ Macedonian weapons for a duel with the Athenian Dioxippus.⁵⁸ These arms included a small shield, a spear (which Curtius emphasizes was called a sarissa), a ‘lance’, and a sword (Macedo iusta arma sumpserat, aereum clipeum hastamque – sarisam vocant – laeva tenens, dextera lanceam gladioque cinctus). The correlation between the lance of Curtius and the javelin is confirmed by Diodorus who states that, during the ensuing contest, Coragus first cast ajavelin at Dioxippus and then lowered his sarissa and advanced.⁵⁹ This would suggest that, while not recorded in the ancient texts, phalangites were capable of carrying both weapons at the same time. This would only be possible if the phalangite was initially stationary as this would then allow him to hold the sarissa upright in his left hand, cast the javelin with his right, deploy the pike, and then move forward (just as Diodorus recounts). However, if such an action was ever adopted for battle in a massed formation, it would seem unlikely that anyone other than the members of the front ranks would be able to cast javelins due to all of the vertically raised pikes.

Interestingly, if a javelin of some description was a common feature of the phalangite’s panoply, this sheds light on the passage of Polyaenus which refers to the Macedonians ‘skirmishing with missiles’ (ἡκροβολίσαντο) during their encounter with Onomarchus in 353BC (see page 20).⁶⁰ It is possible that, at the beginning of this engagement, some of the phalangites first cast javelins at the enemy and then followed this up with an advance of levelled pikes. This would then correlate the actions of just a pike-phalanx with what Polyaenus states rather than the other option for reading the passage which has skirmishers engaging first followed by an advance of the pike-phalanx (see page 21). However, the fact that no such action is recorded anywhere else for a battle up to the end of the Hellenistic Age, other than the duel between two of Alexander’s men, suggests that Horratus/Coragus had employed a ‘heroic’, and versatile, form of combat for his duel. Dioxippus is similarly described as fighting in a ‘heroic’ fashion – in the guise of Heracles, naked and armed with a club.⁶¹ Unfortunately, what none of the sources provide is where the javelin that Horratus/Coragus was using had come from and it is interesting to note that Curtius’ description of it as part of the ‘regular’ equipment of the Macedonians suggests that the portage of both a pike and a javelin may have been a relatively common occurance.

McDonnell-Staff suggests that phalangites carried not only their sarissae but a short (1.5-1.8m long) throwing/stabbing weapon called a longche as well.⁶² However, the term longche may not necessarily be a reference to a javelin. Plutarch, for example, describes the troops of Antiochus in 196BC as ‘longche bearers’ (λογχοφόροι), but this is not necessarily indicative that they carried both this weapon and a sarissa – indeed the term λογχοφόροι is usually translated as ‘pikemen’ which would suggest that the longche and the sarissa were the same (or at least a similar) thing.⁶³ The term longche (λογχἡ) is generally only used by Classical Age writers to describe spears that are foreign in origin.⁶⁴ Plutarch, similarly using the term to describe a foreign weapon, states that Philip’s thigh was pierced by a longche in a battle against the Triballians.⁶⁵ The use of the term longche would also be applicable to Greek descriptions of Macedonian weapons as the Greeks always viewed the Macedonians as slightly foreign and living on the fringes of the civilized world.⁶⁶

The other possibility is that the term longche refers to the use of the front half of the sarissa as an improvised weapon. According to Arrian, one of the accounts of when Alexander the Great killed the general Cleitus in a drunken rage in 328BC, stated that the weapon that Alexander used was a longche which he had snatched away from one of his guards.⁶⁷ Hammond suggests that the guards were armed with sarissae – which would then make the terms longche and sarissa interchangeable.⁶⁸ However, a lengthy pike would be somewhat unwieldy indoors and not entirely suitable for someone acting as a guard protecting a king. This suggests that the guards were carrying a shorter weapon that they could use indoors and which was effective outside the massed formation of the phalanx. This again suggests that the longche may have only been the front half of a sarissa. Curtius called the killing weapon a lance (lancea) – the same name he uses for the javelins used to execute Philotas.⁶⁹ Plutarch also says Cleitus was killed with a lance (aichmē – αἰχμή).⁷⁰ This again would correlate with the use of only the front half of the sarissa.

Two inscriptions from Epidaurus, dated to the second half of the fourth century BC, the time when Philip and Alexander were campaigning against Greece with their ‘foreign’ weapons, detail how two ‘walking wounded’ visited the sanctuary of Asclepius to have wounds received from a longche cured (nos. 12 and 40).⁷¹ One sufferer, Euhippus, had carried the head of the longche lodged in his jaw for six years! The other sufferer, Timon, had received a wound under the eye. What these inscriptions unfortunately do not tell us is whether these wounds were inflicted with a thrown or thrusted weapon.

It is also possible that the term longche is the correct name for a pike that comes in two parts, while the term sarissa could be the name for a single piece weapon – a name that later became a generic term for the Macedonian pike regardless of its configuration. If this is the case, then the Macedonian phalangite could have carried either a dual or single piece weapon depending upon the unit he was attached to and the duties that this contingent was expected to undertake. While the attribution of the term longche to a throwing/stabbing weapon used by Macedonian phalangites may not be accurate, McDonnell-Staff’s conclusion that they carried such a weapon may be partially correct if it is assumed that the longche is the sarissa; either the front half or the whole pike. Either interpretation would then account for Plutarch describing pikemen as ‘longche bearers’.

When Hellenistic armies stormed cities that they were besieging, it is unlikely that any phalangites involved in the action were carrying their pikes while using such equipment as assault ladders or siege towers.⁷² In the late third century BC, Philopoemen also used caetrati-pikemen in an amphibious night assault against the Spartans.⁷³ These troops are described as being armed with skirmishing weapons.⁷⁴ Williams suggests that these troops, while ordinarily pikemen, were using smaller weapons for this encounter as a lengthy pike would have been too cumbersome to carry on small boats, to carry over hilly terrain, and to use effectively at night.⁷⁵ However, it cannot be discounted that pikemen in such engagements may have only been using the forward halves of their sarissae. Similarly, Plutarch recounts how Antigonus wrote a message in the sand using the butt of his weapon.⁷⁶ It is unlikely that he was using a pike or cavalry lance over 5m in length to do this – either he was wielding a more traditional spear at the time, or was using one half of a sarissa.⁷⁷

Arrian states that the shaft of the Macedonian cavalry lance was fashioned from the wood of the Cornelian Cherry (κράvεια).⁷⁸ Cornelian Cherry was also used to make the shafts of spears as well as bows, javelins and other weapons, predominantly used by non-Greeks.⁷⁹ However, there is no direct reference to the wood that the shaft of a sarissa was made from. Theophrastus uses the height of the Cornelian Cherry as a comparison for the length of the sarissa in the fourth century BC, but does not actually state that it was used to fashion its shaft – although many scholars interpret this passage as saying such.⁸⁰ According to Theophrastus, this tree had a height of about 12 cubits (576cm). Interestingly, Theophrastus states that the Cornelian Cherry has a relatively squat trunk and few long straight branches. As such, it is difficult to get a single piece of straight timber more than a few metres in length from this tree. Consequently, if the convention that the shaft of the sarissa was made from Cornelian Cherry is accepted, then it must also be accepted, by default, that the shaft came in at least two sections and thus required a connecting tube to hold it together – a consideration which seems to have escaped many scholars who argue for the use of this wood to fashion a single shaft for the sarissa (see also the following section on The Shaft of the Sarissa from page 63).

Other scholars assign a different purpose to the tube found by Andronicos – claiming that it is a foreshaft guard used to protect the shaft from being hacked through by an opponent.⁸¹ Manti claims to see such foreshaft guards in the Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii.⁸² However, what appears to be depicted in this mosaic are not separate foreshaft guards, but the socket of the small leafshaped head of the sarissa as there seems to only be a single item, rather than two separate pieces, mounted on the forward end of the weapon (Plate 5).

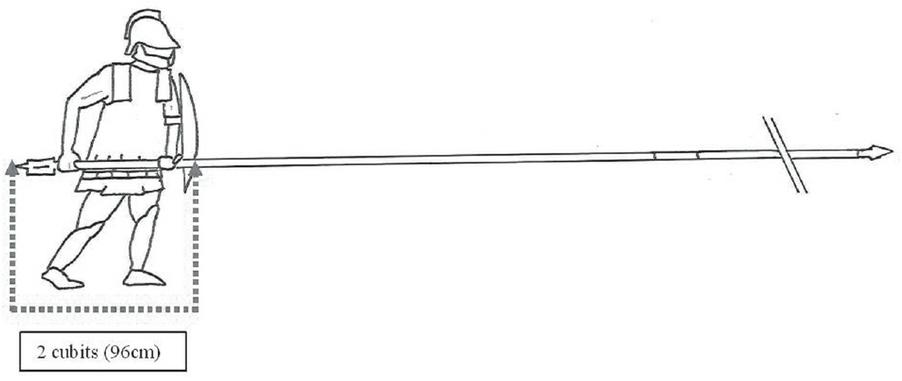

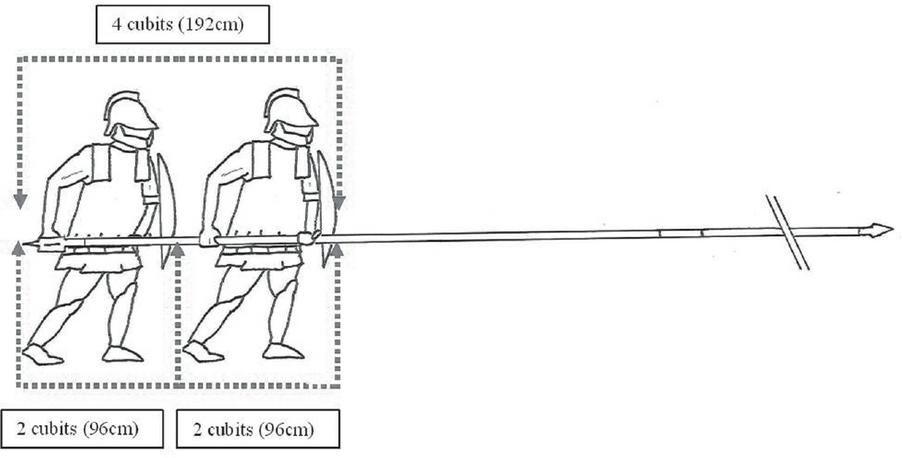

Manti also uses the size of the tubular ‘guard’ as proof for the existence of a smaller unit of measure in the Hellenistic world incorporating a cubit of 33cm (for the different models for the units of measure in the Hellenistic world see the following section on The Length of the Sarissa from page 66). Manti claims that the length of the ‘guard’, plus the head, equals a distance of 66cm or 2 cubits using this smaller standard.⁸³ This theory has to assume the use of a head similar to the larger of the two found at Vergina by Andronicos with a length of around 49cm. Manti concludes that, as the intermediate-order outlined by many of the ancient writers incorporates a spacing of 2 cubits per man, and because any weapon held by a more rearward rank would extend ahead of the line by an amount shorter than the weapon of the man in front by 2 cubits due to the interval he occupies, the first two cubits of the sarissa shaft had to be protected by the head and a foreshaft guard.⁸⁴

The problem with this conclusion is that it is impossible for a phalangite to stand in a space only 66cm in size and deploy his weapon for combat while still conforming to the spatial requirements of the phalanx (see the chapter on Bearing the Phalangite Panoply from page 133). The minimum amount of space required is 96cm – based upon a system of measurements using a 48cm cubit rather than a smaller one of 33cm. Thus, 66cm does not actually equate to a measurement of 2 cubits, and any formation using the larger interval will present a serried wall of pikes with each successive weapon stepped back from the one held by the man in a more forward rank by 96cm rather than 66cm. As such, the ‘exposed’ parts of the weapon would not actually be wholly protected by the head and a ‘foreshaft guard’ only 17cm in length as Manti suggests.⁸⁵ This brings the interpretation of the small ‘foreshaft guard’ into question.

Another problem with Manti’s interpretation is because the large ‘head’ found by Andronicos is used in the reconstruction. What conclusively illustrates that the metallic tube was not positioned immediately behind the large ‘head’ in the role of a foreshaft guard, is that the diameter of the socket for the large ‘head’ and the tube are different sizes. The socket of the head found by Androncos has a diameter of 36mm with the thickness of the wall of the socket ranging between 2-3mm. This would mean that the opening in the socket could accommodate part of the shaft that is between 30-32mm across.⁸⁶ However, the largest end of the metal tube found at Vergina has a diamter of 32mm, and a thickness ranging between 3-5mm, giving a size of the inner socket of somewhere between 22-26mm. It is interesting to note that the tube found at Vergina is not a solid cylinder. Rather it is a sheet of metal that has been wrapped around the shaft of a weapon. This is evidenced by a longitudinal split that runs the length of the tube.⁸⁷ Thus the tube could be fashioned to fit to a shaft of any diameter. It is possible that the tube has been compressed during the time prior to its recovery and that its diameter may have been slightly larger (which would then allow for it to be used as a foreshaft guard as some have suggested). However, the relative unifomity of the diameter of the tube as it currently exists would suggest otherwise and that its current diameter of 22-26mm is accurate. This then indicates that the socket of the large ‘head’ found at Vergina and the tube cannot have been abutted against each other, with the tube acting as a foreshaft guard, unless it is assumed that the thickness of the shaft was considerably reduced just behind the head in order to accommodate a guard of plate metal. This seems unlikely. However, if viewed as a connector, a split tube could be easily refashioned for use with replacement shafts which may not have been made to the exact specifications of the original weapon.

The final problem with the interpretation of the tube as a foreshaft guard is that, if positioned just behind the head, the addition of 200g of weight to the forward end of the weapon greatly affects the position of the balance unless the head is correspondingly reduced in size to a point where it would almost be offensively redundant (see the following section on The Balance of the Sarissa from page 81).

It is also possible that the tube was used to repair a split in a shafted weapon – although this may not have nescessarily been a sarissa. However, it would seem odd to include a broken weapon in the grave goods of the tomb of a Macedonian noble unless it is assumed that it was his personal weapon – perhaps one that he had been campaigning with for some time and had even died with. This would then account for the state of the weapon buried with him if the tube was indeed used as a repair. Alternatively, it is also possible that the tube was wrapped around the the shaft of a weapon in a particular location in order to adjust the distribution of weight so as to provide the weapon with its correct point of balance. The addition of extra weight to specific points of a shafted weapon was occasionally undertaken by the Classical Greek hoplite as evidenced by the sauroter of a hoplite spear now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens (#6848) which has a ball of lead wrapped around it to add to the overall mass of the rearward end of the weapon which, in turn, would then alter the spear’s point of balance (presumably to the correct one). Thus the use of a metal sheet, wrapped around the shaft, to correct a weapon’s point of balance cannot be discounted as a possible function of the tube recovered from Vergina.

Finally, it must also be conceded that it is possible that the tube did not belong to a sarissa at all, but was part of the configuration of some other weapon or implement – such as the staff upon which a banner of some description hung. However, the logistical and tactical benefits of using a sarissa which came in two parts, and was then assembled for use in battle, suggest that this is the most viable interpretation for the configuration of the sarissa. Consequently, a mechanism had to be used to join the two halves of the weapon together. The most likely form of this mechanism, and the most likely purpose of the tube found at Vergina by Andronicos, is that it was a connecting tube for the sarissa.

Importantly, it is not only the weight of the head and butt-spike which affects the dynamics and performance of the weapon, but also the configuration of the shaft as well. Here, like every other aspect of the design of the sarissa, scholarship does not agree. Some scholars state that the shaft of the sarissa was of a uniform diameter. Many of the proponents of this theory are those who accept the theory for the large ‘head’ found at Vergina being the tip of the sarissa. As both this large ‘head’ and the butt-spike found at the same time possess sockets with a similar size, some scholars have therefore concluded that the shaft had to have a uniform diameter of around 39mm along its entire length.⁸⁸

Conversely, other scholars suggest that the shaft of the sarissa was tapered – with a smaller diameter at the front enlarging to a diameter of around 34mm at the rear.⁸⁹ Scholars who forward this theory are generally those who have rejected the identification of the large ‘head’ from Vergina as being that of the sarissa and favour the use of the smaller head with its narrower socket. In his examination of Greek armour and weapons, Snodgrass states that the shaft of the sarissa was obviously tapered as the weapon lacked a butt.⁹⁰ However, it must be noted that when Snodgrass first composed his work (1967) the butt at Vergina had not yet been discovered by Andronicos.

As has been demonstrated, there are immediate problems with both models. The large ‘head’ from Vergina is more likely to be the butt of a Hellenistic cavalry lance while the smaller head is most likely that of a javelin. As such neither model is using the correct constituent parts in their reconstruction of the configuration of the sarissa.

Unfortunately, while ancient sources like Arrian or Theophrastus provide one possibility for what wood the shaft of the sarissa was made from, such passages do not detail its exact shape. The Cornelian Cherry was relatively common throughout northern Greece, Asia Minor and Syria. However, despite these references, it cannot be automatically assumed that weapons were exclusively made from this type of wood. Both Tyrtaeus and Homer refer to ash being used to construct spears during earlier periods of Greek history.⁹¹ Roman writer Statius specifically states that the Macedonians used sarissae made of ash (fraxineas Macetum vibrant de more sarisas) and Theophrastus says that this type of tree was common in Macedon.⁹² Pliny the Elder states that ash was a good wood for a spear shaft as it is lighter than the Cornelian Cherry and is more pliant than the ‘service-tree’.⁹³ Thus Pliny’s passage compares three different types of wood that had been, or were currently, used in the construction of weapons. In his third century BC treatise on siege warfare, Biton states how oak or ash should be used in the construction of the wheels and axles of war machines and artillery due to the strength of the wood. He further recommends that fir or pine be used to create the superstructure of these engines due to the strength of the wood.⁹⁴ Therophrastus also outlines the strength and lightness of oak.⁹⁵ It seems unlikely that woods that were known for both their lightness and strength would not be used in the manufacture of weaponry. It can therefore only be assumed that weapons in the Hellenistic period were fashioned from a variety of woods to create an optimum blend of lightness, strength and rigidity.⁹⁶

It must also be considered that replacement shafts would have been made from whatever timber was available to an army in the field. It is unlikely that a campaigning army would have waited until they came across a grove of Cornelian Cherry before they replaced and/or repaired any damaged weaponry. English suggests that replacement shafts, made from Cornelian Cherry, were shipped to Alexander’s army from Macedonia. This seems unlikely for several reasons. Firstly, and assuming that the shafts were made exclusively from Cornelian Cherry to begin with, if troops operating in Syria, for example, needed to repair or replace damaged weapons, they are unlikely to have waited for shafts to be sent all the way from Macedonia when the same timber was commonly available where they were. Secondly, if troops needed to repair their weapons quickly, they are unlikely to have waited for shafts made from a particular type of timber when something else that was closer at hand may have been both easier and quicker to fashion. Xenophon details how spoke-shaves were carried by Classical Greek armies when on campaign.⁹⁷ The later Macedonians are likely to have followed a similar practice. Dio Chrysostom (2.8-9) suggests that carpentry was one of the three most common occupations in Macedon prior to the time of Philip II, and Alexander’s troops were able to manufacture all sorts of wooden items from furniture to defensive stakes (Arr. Anab. 4.2.1, 4.21.3, 4.29.7; Diod. Sic. 17.95.1-2). This suggests that, no matter which species of wood the shaft may have been initially manufactured from, replacement shafts could, and would, be fashioned from whatever timber was available to a Macedonian army in the field.

Regardless of which wood was used in the construction of the sarissa, the ancient texts omit details of both the diameter of the shaft and how its ends were shaped to accommodate the mounting of the head and the butt-spike. The artistic record is also of limited value in this regard as well. Depictions of the sarissa, such as those on the Alexander Mosaic, on funerary stele, or in Hellenistic tomb paintings generally show a shaft with a uniform thickness rather than one with a taper. However, this may simply be the result of the ability of the artist and the medium used to create the image. One thing that should be considered is that the fashioning of a tapered shaft, particularly one over 5m in length, would require a high level of skill to manufacture accurately on the massed scale that would be required for the equipping of large Hellenistic armies.⁹⁸ Only experienced weapon makers could have manufactured such weapons. This leaves several possibilities. Firstly, that the sarissa was made with a tapered shaft by skilled craftsmen and that, if a phalangite’s weapon broke while he was on campaign, he would have to wait for a replacement shaft to be made and/or delivered before his weapon could be repaired. On the other hand, if the shaft of the sarissa was made with a uniform width, and came in two pieces as the interpretation of the ‘connecting tube’ found at Vergina would suggest, then replacement shafts could be fashioned easily in the field using a spoke shave by troops themselves from whatever timber was available at the time.

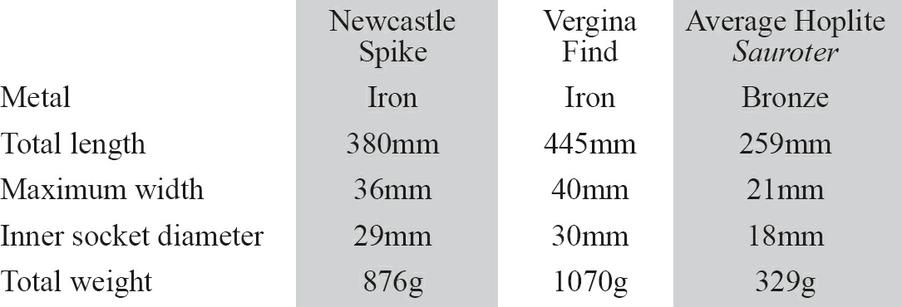

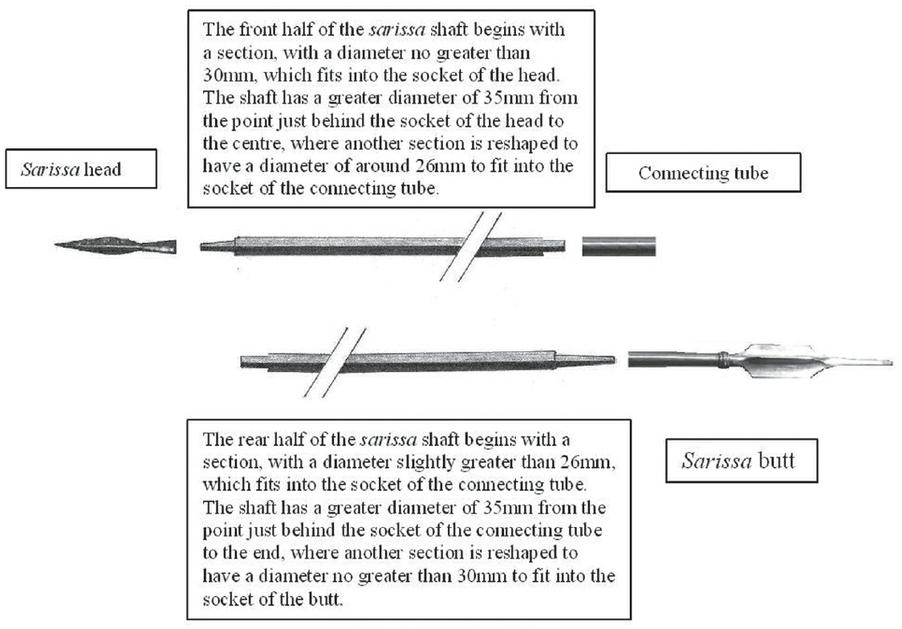

Fig. 2: The configuration of a sarissa with a uniform shaft.

The logistical expediency of having an army that was able to fashion and repair its own weaponry would suggest that this later scenario was the case and that the sarissa came with a uniform shaft. Consequently, if the butt of the sarissa possessed a socket with an inner diameter of about 30cm, and the walls of the socket are about 2-3mm thick, it can be concluded that the sarissa had a uniform shaft approximately 35mm in diameter – the ends of which would have been reshaped in order to accommodate the mounting of the head, butt and the connecting tube in the centre. The connecting tube, 32mm in diameter and with an inner socket of between 22-26mm, could easily be set onto a shaft with a larger diameter if the sections designed to insert into it were similarly reshaped to fit or if the rolled sheet of the tube was ‘opened’ slightly so that the elasticity of the metal would allow the smaller diameter tube to grip tightly onto a shaft with a slightly larger diameter (Fig. 2).⁹⁹

The overall length of the sarissa would include not only the shaft of the weapon, but the size of the butt and the head as well. The ancient military writer Asclepiodotus, writing at the turn of the first century BC, states that the sarissa (which he gives the same name as the hoplite spear (doru)) should be:

no shorter than ten pēcheis (πήχεις), so that the part that projects forward of the line is no less than eight pēcheis. In no case, however, is the weapon longer than twleve pēcheis so as to project ten pēcheis.¹⁰¹

The pēchus was an ancient unit of measure otherwise known as the ‘cubit’. Aelian, writing 200 years after Asclepiodotus in the early years of the second century AD, but basing his work on tactics upon much earlier treatises, recommends that the pike (which he also calls a doru) should be ‘no shorter than 8 cubits and the longest no longer than a man could use and wield effectively’ (a size which he, unfortunately, does not specify).¹⁰² Thus it appears, upon initial reading, that these two passages are at odds with each other in terms of the size of the sarissa that they describe. However, Devine finds similarities between the terminology used by Asclepiodotus (δόρυ δὲ αὖ oὐκ ἔλαττον δεκαπήχεος, ὥστε τὸ προπῖπτον αὐτοῦ εἶναι οὐκ ἔλαττον ἢ ὀκτάπηκυ) and the terminology used by Aelian (δόρυ δὲ μὴ ἔλαττον ὀκταπήχoυς) and suggests that a central section (equivalent to the underlined part of Asclepiodotus’ passage above) is missing from Aelian’s text.¹⁰³ Devine concludes that both Asclepiodotus and Aelian are saying fundamentally the same thing: ‘the spear [i.e sarissa] is not less than 10 cubits long and extends beyond the rank not less than 8 cubits’. If correct, both accounts outline the use of a weapon with a length of 10 cubits; with Asclepiodotus elaborating on a lengthier weapon of 12 cubits, which may be attributable to the weapon that Aelian refers to as the longest one which ‘a man could use and wield effectively’.

Theophrastus, writing just after the death of Alexander the Great (c.322BC), states that the Cornelian Cherry tree grows to a height the same as the length of the longest sarissa – which he gives as 12 cubits.¹⁰⁴ The fact that Theophrastus refers to the ‘longest’ sarissa being 12 cubits in length implies that he was aware of shorter weapons as well – possibly the 10 cubit weapons mentioned by Asclepiodotus and Aelian. Thus there are four references, by three different authors from three different time periods, which are similar to each other; two definitively describing a weapon of 10 cubits and two a weapon of 12 cubits (plus a possible inference to the 12 cubit weapon by Aelian and a possible inference to the 10 cubit weapon by Theophrastus).

Polyaenus states that the garrison of Edessa was armed with sarissae 16 cubits in length when it fought against Cleonymus of Sparta at the end of the fourth century BC (c.300BC).¹⁰⁵ This length seems to be confirmed by Polybius who, writing just after the Roman defeat of the Macedonian phalanx at Pydna in 168BC, states that the sarissae used in earlier times were 16 cubits in length but, at the time he was writing, the weapon had been shortened to 14 cubits.¹⁰⁶ Somewhat confusingly, Aelian, two chapters after he possibly discussed a 10 cubit weapon, then echoes the writings of Polybius by stating that ‘the length of his [i.e. the phalangite’s] pike was initially 16 cubits, but in truth it ought to be 14 cubits’.¹⁰⁷

These references to weapons of varying lengths have led to a number of different interpretations as to the size of the sarissa at different points throughout the Hellenistic Period. Sekunda, for example, states that because Theophrastus is writing after the time of Alexander the Great (albeit only by about a year), the weapons used in Hellenistic armies after Alexander died were 12 cubits in length.¹⁰⁸ Heckel and Jones, on the other hand, cite Theophrastus as evidence that the weapons used in the armies of Alexander and his father Philip were between 10 and 12 cubits in length.¹⁰⁹ Markle states that the best literary tradition says that the weapons used by the armies of Alexander and the Successors were between 10 and 12 cubits despite references to longer weapons being used in the later Successor Period.¹¹⁰ Everson only states that the weapons carried by the armies of Philip and Alexander were 12 cubits in length without elaborating on when he thinks a 10 cubit weapon may have been used or whether the usage of 12 cubit weapons continued after Alexander’s death.¹¹¹ Similarly, Snodgrass flatly states that the sarissae used throughout the fourth century BC were 12 cubits in length as per Theophrastus without any consideration of the evidence that implies the existence and/or usage of both shorter and longer weapons during this same period.¹¹²

Despite this somewhat confusing and contradictory corpus of scholarship on the length of the sarissa, it is possible to trace an evolutionary path for the size of the weapon from these ancient sources themselves. Two of the ancient accounts provide details of the length of the sarissa at a specific point in time during the Hellenistic Period. Polyaenus, for example, gives a length of 16 cubits for weapons used around the year 300BC (or 274BC according to Hammond and Walbank). Additionally, Polybius states that the weapons before his time (c.168BC) were 16 cubits in length but had subsequently been shortened to the 14 cubit weapons used in his day. The similarity between the passages of Polybius (18.29.2) and Aelian (Tact. 14) suggest that, at least in this latter passage, Aelian was commenting on the weapons of the mid-second century BC as well (if he was not just paraphrasing Polybius’ passage without considering that it contradicts with what he had written earlier). In his introduction, Aelian advised the Emperor Hadrian (to whom the work was dedicated) that he may find a small pleasure in the fact that contained within the book were Alexander of Macedon’s ways of marshalling an army.¹¹³ This would suggest that much of the work (and also that of Asclepiodotus upon which it may have drawn) recounts the details of a Hellenistic army, including the size of their weapons, in the mid-late fourth century BC. However, the similarity between the passages of both Aelian and Polybius suggest that Aelian was, in fact, drawing upon sources which recounted the use of different length sarrisae throughout the whole Hellenistic Period.

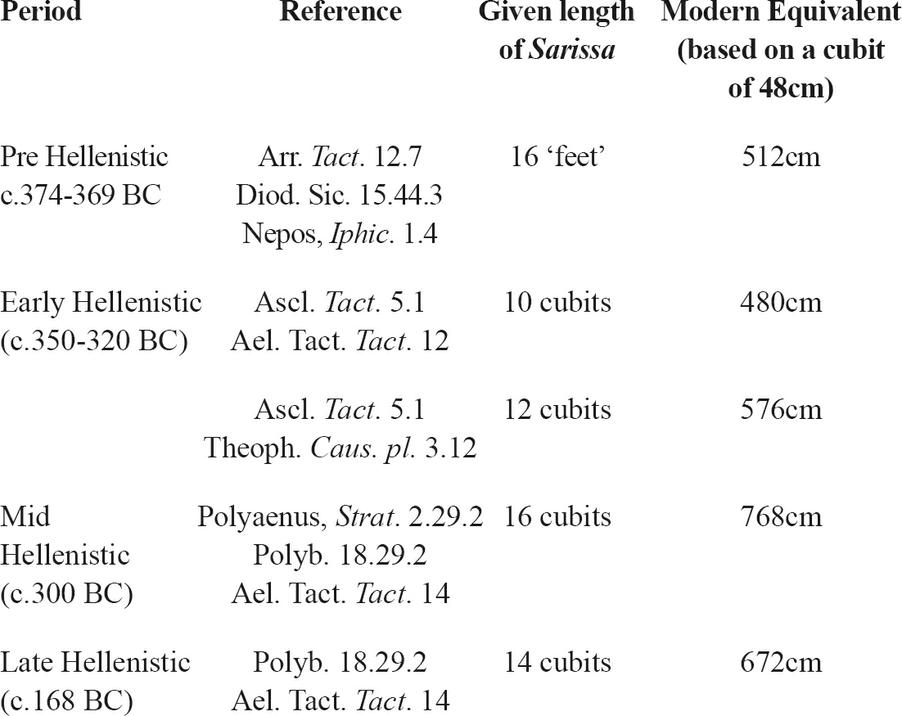

Like Polybius, Theophrastus must also be referring to a weapon that existed in his own time (the late fourth century BC) and place of writing (Athens) as he uses it as a basis of comparison for the height of the Cornelian Cherry tree.¹¹⁴ It would have been redundant for Theophrastus to have used the details of a weapon that would not have been commonly known to his intended audience as the basis for his comparison. This suggests that the sarissae at the time Theophrastus was writing were commonly 12 cubits in length. This suggests that the 10 cubit weapons detailed by Asclepiodotus and Aelian are references to pikes used in the early Hellenistic Period, and that the length of these weapons was increased to 12 cubits by the time of Theophrastus. From all this it seems that, in the mid-fourth century BC, the sarissa was between 10 and 12 cubits in length – the longest being deemed the greatest that a phalangite could wield effectively in battle. Despite this claim, by the end of the century, the length of the weapon had increased to 16 cubits only for the length to be subsequently reduced back to 14 cubits sometime before the end of the Hellenistic Period in the mid-second century BC (Table 2).

| Reference | Given length of Sarissa | Time Period Referred To |

| Ascl. Tact. 5.1 | 10-12 cubits | Early Hellenistic Period |

| Ael. Tact. Tact. 12 | Possibly 10 cubits | Early Hellenistic Period |

| Theoph. Caus. pl. 3.12 | 12 cubits | Early Hellenistic Period |

| Polyaenus, Strat. 2.29.2 | 16 cubits | Mid Hellenistic Period |

| Polyb. 18.29.2 | 16 cubits reduced to 14 cubits | Mid-Late Hellenistic Period |

| Ael. Tact. Tact. 14 | 16 cubits but really 14 cubits | Mid-Late Hellenistic Period |

Table 2: References to the size of the sarissa for different time periods.

A further problem comes from converting the given lengths for the sarissa into modern equivalents. This is due to various interpretations of the size of the cubit. This problem is compounded by the fact that units of measure were not always standardized across the ancient Greek world but often varied from state to state. The smallest unit of measure was the daktylos (δάκτυλος) – a unit representing the thickness of a finger.¹¹⁵ Four daktyloi made a ‘palm’ (παλαστή). Herodotus states that ‘a foot (πούς) equaled four palms and a cubit equaled six palms’.¹¹⁶

Many scholars either argue for, or use in their examinations of Hellenistic warfare, an Attic daktylos of 1.8cm which results in an Attic cubit of 45cm.¹¹⁷ However, a metrological relief, which has been dated to the time of Alexander the Great at the earliest, found on the island of Salamis in 1985, contains a measurement for a daktylos of 2.0cm, a foot of 32.2cm and a cubit of 48.7cm.¹¹⁸ A daktylos of 2.0cm should, following the scale of increments outlined by Herodotus, result in an even foot of 32.0cm and a cubit of 48.0cm.¹¹⁹ Dekoulakou-Sideris suggests that any discrepancy, which is only in millimetres, is attributable to a lack of precise stone cutting on the part of the mason who carved the metrological relief.¹²⁰ Thus it seems more likely that the Attic cubit at the time this relief was made was closer to 48.0cm than it was to 45.0cm. Other regions used a unit of measure similar to this larger Attic standard, with variances measured only in millimetres. The Olympic, or Peloponnesian, standard for example, was also based upon a foot of 32cm – which would equate to a daktylos of 2cm and a cubit of 48cm.¹²¹ The cubit was also measured as the distance between the tip of the elbow and the tip of the middle finger: On a person with an average height of 170cm (see below), this measures around 48cm. This further suggests that the cubit was in the vicinity of 48cm within most of the systems used across Greece.¹²²

In an investigation of ancient construction techniques, Broneer identified what he called a ‘Hellenistic foot’ of 30.2cm – so named because it was believed to have come into use during the time of Alexander the Great.¹²³ This smaller foot would be based upon a daktylos of 1.9cm and a corresponding cubit of 45.4cm. The representation of what appears to be one of these ‘Hellenistic feet’ of 30.1cm also appears on the Salamis Metrological Relief and is what is used to date the engraving. This may be where modern references to a 45cm Attic cubit in the Hellenistic Period have originated. However, if so, such claims would ignore the presence of a 48.7cm cubit on the same relief.

Another metrological relief, now in the Ashmolean Museum, contains a representation of a ‘foot’ which measures 29.6cm. Michaelis calls this foot ‘Samian’ and believes that it was an Attic foot added later to the relief when Samos came under Athenian control in the fifth century BC.¹²⁴ Such a foot would, if accurately depicted, be part of a system incorporating a daktylos of 1.8cm and a cubit of 44.4cm; not far removed from the supposed ‘Hellenistic’ standard identified by Broneer. However, Dinsmoor’s examination of the measurements of the buildings on the Athenian Acropolis, and other classical buildings in Attica, shows that the ‘foot’ that was in use in Attica in the mid-late fifth century BC measured 32.6cm (with a resultant cubit of 48.9cm).¹²⁵ If Michaelis is correct about the smaller cubit being an Attic measurement from the time when Samos came under Athenian control (early fifth century BC), it appears that this unit was replaced a few decades later with a larger unit of 48cm based upon the Olympic/Peloponnesian standard. Consequently, Broneer’s ‘Hellenistic foot’ should actually be relabeled as an ‘early-Attic foot’ instead. This change from one standard system of measurements across the Greek world to another was most likely a result of the ‘Coinage Decree’ that was initiated by Athens to standardize all weights, measures and currency used in its allies, colonies and territories.¹²⁶ The dating of this decree has been controversial. Initially dated to around 430BC, stylistic considerations of a fragmentary epigraphic record of the decree from the island of Kos forced some scholars to revise this date to between 449BC and 445BC (which corresponds with the construction of the Acropolis under the building programme of Pericles). Further evidence in the form of another epigraphic copy of the decree from Hamaxitos, which became part of the Athenian empire in 427BC, has forced some to revise the date of this decree again to around 425BC.¹²⁷

Regardless of the date of the actual decree, part of the standardising process must have been the imposition on the Athenian allies of a system of measurements based upon a daktylos of 2cm, a ‘foot’ of 32cm and a cubit of 48cm – a system of units that Athens itself appears to have adopted sometime before the construction of the Parthenon and the other buildings of the Acropolis in the mid-fifth century BC. Units of a similar measure were already in use in the Peloponnese and other parts of Greece as well as in Sicily and the Greek colonies in the west. By ‘converting’ all of its subjects and allies in the Aegean over to a unit of measure that was common throughout the rest of the Greek world, Athens not only facilitated trade among all the regions of Greece, and imposed another way of ensuring Athenian domination of its subject allies, but created a standardized system of measurements across the entire sphere of Hellenic influence that would continue to be used for centuries to come. Thus it is this unit of measure that is most likely the system that the ancient writers were using in their references to the length of the sarissa. Theophrastus for example, can only have been basing his comparison of the height of the Cornelian Cherry tree and the length of the sarissa on a contemporary local unit of measure that his audience would readily understand. This suggests that the weapons in service around the time that Theophrastus was writing were twelve ‘late-Attic’ cubits, or approximately 576cm, in length.

However, further controversy over the size of the sarissa arises from a number of theories that have been forwarded which suggest the cubit commonly used throughout Greece was of a different size again. In the 1880s, Hultsch suggested that the cubit measured 46.2cm while Dörpfeld suggested that it measured 44.3cm.¹²⁸ Then, in 1930, Tarn suggested the existence of a short ‘Macedonian cubit’ of only 33cm.¹²⁹ Tarn based his conclusions on two different factors. Firstly, he deduced that, as he believed that the Macedonian ‘bematist’s stade’ measured three-quarters of the Attic stade, all other Macedonian units of measure should follow suit when compared to the Attic. Secondly, Tarn claimed to have found the ‘proof’ of the existence of a short ‘Macedonian cubit’ in the writings of Arrian. Contained within his narrative history of the campaigns of Alexander the Great, Arrian describes the Indians as being the tallest race in Asia with most of them being over 5 cubits in height or not much less.¹³⁰ Later in the narrative, Arrian describes the Indian king Porus as ‘a magnificent example of a man, over 5 cubits high’.¹³¹ Arrian’s description of Porus is echoed in the works of Diodorus while Plutarch gives the king a height of 4 cubits and one palm.¹³²

Tarn, taking the ancient sources to be accurate descriptions of the king’s stature, concluded that the authors (or at least their sources) had to have been giving measurements based upon a smaller Macedonian cubit of 33cm as this would give Porus a realistic height of 165cm. Tarn dismissed the possibility that Porus’ size was given in larger Attic cubits as the resultant stature of 225cm (based upon the early-Attic cubit of 45cm) was unrealistically large. Tarn concedes that Arrian’s use of the word ὑπέρ (meaning over, exceeding or beyond) to describe Porus’ stature suggests that the given height is exaggerated, but concluded that the base of five cubits was an accurate measurement.¹³³

Tarn’s suggested small Macedonian cubit has raised more problems than it has solved in the study of ancient military history and has become an integral part of a debate that has raged over which unit of measure was used by which ancient writer and, subsequently, over the size of the sarissa mentioned in these ancient sources. Tarn himself, for example, suggests that Theophrastus was writing in terms of his small Macedonian cubits.¹³⁴ Alternatively, Mixter uses a cubit of 45cm for the basis of his examination into the sarissa in the fourth century BC.¹³⁵ Manti, on the other hand, accepts the existence of Tarn’s 33cm bematist’s cubit and suggests that this became the standard system of measurements in the wake of the Hellenisim spread by Alexander’s advancing army.¹³⁶ Strangely, in an attempt to reconcile the sizes given by both Theophrastus and Asclepiodotus with those of the other authors (which Manti claims are all using the smaller cubit) Manti suggests that Theophrastus was using the Attic cubit as his standard and Asclepiodotus either copied Theophrastus or a contemporary source. Such a conclusion seems odd when it is considered that, even though Theophrastus was writing in Athens, he was writing just after the time of Alexander when Manti suggests that the smaller Macedonian cubit had already become the standard. Manti claims that both Theophrastus and Asclepiodotus are describing a weapon 5.4m in length (based upon 12 x 45cm cubits) that was in use in the time of Philip and Alexander and that this weapon was subsequently replaced by a smaller 4.8m weapon (based upon 14 smaller Macedonian cubits of 33cm) which he says is what is being described by Polybius and Aelian.¹³⁷

Dickinson, in his examination of the sarissa, also claims that Polybius based his discussion of the Hellenistic phalanx on Tarn’s smaller Macedonian cubit.¹³⁸ Such conclusions completely ignore statements like that made by Polybius himself which refer to the use of longer weapons during the late Hellenistic period of 16 cubits which, even in the smaller standard, equate to 5.3m in length – bigger than the supposed longest weapon used in the period according to Manti. Conversely, both Markle and Lane Fox flatly dismiss the existence of Tarn’s proposed short Macedonian unit of measure and use a 45cm cubit in their examinations.¹³⁹

By examining the evidence presented by Tarn, this mire of scholarly debate can be cleared. The evidence indicates that both sides of this debate are, in fact, incorrect. Not only does the review of this evidence show that a 45cm cubit was unlikely to have been that used by the ancient writers, it also shows that the claims for the existence of a 33cm Macedonian cubit, and subsequently all scholarship that is based upon it, are unfounded.

Firstly, there is little evidence that the ‘bematist’s stade’ was based upon a unit of measure incorporating a cubit of 33cm. The bematists were specialist surveyors – trained to walk with a regular, measured, step so that accurate distances could be recorded. Several such surveyors accompanied Alexander’s expedition against Persia.¹⁴⁰ Many of the measurements taken by these bematists were later recounted in the works of Pliny and Strabo.¹⁴¹ Engels suggests that the high level of accuracy in the recorded measurements taken by the bematists may be an indication that they used a specific measuring tool to make their calculations – such as the odometer described by Heron of Alexandria.¹⁴²

What the texts of Pliny and Strabo demonstrate is that Alexander’s surveyors were using a system of measurement based upon the larger 48cm cubit implemented by Athens in the mid-fifth century BC. Strabo, for example, recounts that the distance measured by the bematists between Alexandria Arieon (modern Herat in north-west Afghanistan) and Prophthasia (modern Juwain in south-west Afghanistan) was recorded as 1,600 stades.¹⁴³ The stade was an ancient unit of measurement equivalent to 600 Greek ‘feet’. Thus in the system of Tarn’s smaller cubit, which contains a foot of 22cm, the stade is equal to 132m.¹⁴⁴ In the system incorporating the ‘early-Attic’ cubit of 45cm, the stade equals 180m.¹⁴⁵ A stade based upon the larger ‘late-Attic’ system, with its cubit of 48cm, equals 192m.¹⁴⁶ Interestingly, the distance between the start and finish lines in the great stadium at Olympia (the length of the ‘stadium’ being what the term stade is based upon) measures 191m – further proof that the Olympic/Peloponnesian standard incorporated a cubit of around 48cm.

Based upon these different measurements, the distance from Alexandria Arieon to Prophthasia recorded by Strabo calculates to 211km, 288km and 307km when converted into the 33cm cubit system, the 45cm cubit system and the 48cm cubit system respectively. The actual distance between these two locations is 304km, which suggests the use of the larger ‘late-Attic’ cubit in the determination of distance.¹⁴⁷ Many of the other recorded measurements given by Strabo and Pliny, when converted, fall between distances in early and late Attic cubits. This suggests the use of either one or the other system for the recording of measurements with a margin of error of only a few per cent.¹⁴⁸ However, the closeness of the converted and actual distance between Alexandria Arieon and Prophthasia suggests the use of the larger ‘late-Attic’ system. Importantly, even if the ‘early-Attic’ system was the one that was used with a lesser degree of precision, the recording of such distances clearly demonstrate that Alexander’s bematists were not using a system of measurement that incorporated a small 33cm cubit as is suggested by Tarn. Even Tarn himself states that there is no doubt that Hellenistic explorers and navigators used a larger Attic cubit to measure distance, which seems to go directly against his own conclusions – although he does not state which Attic cubit he believes they used.¹⁴⁹ As noted, Manti suggested that the small Macedonian unit of measure became the standard across the Hellenistic world after being spread by Alexander’s advancing army.¹⁵⁰ Such conclusions, however, go against the evidence which clearly indicates the use of a larger (48cm cubit) system by Alexander’s surveyors and it is thus uncertain where the idea of a short ‘bematist’s cubit’ has come from. This in itself suggests that references to the length of the sarissa in the ancient sources are given in cubits larger than Tarn’s 33 cm ‘Macedonian’ standard.

Another reason to dismiss Tarn’s small 33cm cubit is that there is no need to automatically assume that what Arrian and Diodorus are trying to relay in their description of the stature of the Indians or their rulers is an accurate portrayal of size as Tarn suggests. Ascribing ‘larger than life’ characteristics to both enemies and heroes was a relatively common literary motif in the ancient world. Herodotus, for example, claimed that Orestes, the son of king Agamemnon of Mycenae, was 7 cubits (ἑπταπήχεϊ) tall.¹⁵¹ At the battle of Marathon, the Athenian Epizelus was suddenly struck blind by the sight of an opponent of ‘great stature’ (μέγαν).¹⁵² Similarly, Plutarch describes the corpse of the hero Theseus as being of ‘gigantic size’ (μεγάλου σώματος).¹⁵³ Thus, there is no need to automatically assume that Arrian and Diodorus were using a previously unattested smaller Macedonian unit of measure to accurately describe the height of a race of people or their leader. It is more likely that they were basing their descriptions on the standard ‘late-Attic’ cubit of 48cm and using the great height of the Indians and their kings that this implies as a literary construct to portray them as more imposing and to make the succeeding victories of Alexander’s army that occur later in their narratives appear all the more glorious.

Tarn suggested that the presence of 165cm tall Indian warriors (based upon his small 33cm cubit) would have made quite an impression on the ancient Greeks whom he describes as ‘not tall’.¹⁵⁴ However, the evidence indicates that the ancient Greeks were around the same height, or taller, than 165cm on average. The remains of thirteen Spartan warriors unearthed in the Kerameikos in Athens are said to be the same height as that of a modern man – around 170cm.¹⁵⁵ Two other bodies, one of a young adult male and one of a mature male, excavated from near the Herian gates north-east of the Kerameikos (now T35 (case 111) and T37 (case 112) in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens) were dated to the mid-fifth century BC. Their bodies measured 180cm and 175cm respectively. Schwartz, in a review of the measurements of other ancient bodies found in Greece, suggests that the average size for an adult male was between 162cm and 165cm.¹⁵⁶ This all suggests that an average height for the ancient Greeks was around 170cm.¹⁵⁷

Thus it is unclear what impression an Indian opponent of a smaller or similar size, based upon Tarn’s smaller Macedonian cubit, would have had on such men to warrant its mention by Arrian and Diodorus. If Plutarch’s stated stature for Porus of 4 cubits and one palm is taken as accurate, a conversion into Tarn’s Macedonian cubits results in a height of only 137.5cm – much shorter than the average Greek. Clearly all of these ancient writers are trying to give an impression of imposing size. Using the larger ‘late-Attic’ system, Plutarch’s stated stature for Porus equates to 200cm – a height taller than the average Greek and yet still realistic – suggesting that this may be an accurate description of the size of the Indian king. This further indicates that Tarn is in error with his suggestion of the existence of a small Macedonian cubit.

Another element that Tarn failed to consider is that there is an indication of the size of the cubit used by the Macedonians in the writings of Asclepiodotus. Asclepiodotus uses the ‘palm’ as a unit of measurement in his examination of the phalangite’s shield (the peltē) – which he says was eight ‘palms’ (or 32 daktyloi or 2 ‘feet’) in diameter.¹⁵⁸ Aelian gives the same measurements for the Macedonian shield in his treatise on tactics.¹⁵⁹ The diameter of the partial remains of two phalangite shields, found at Dodona and Vegora and dated to the third century BC, were estimated at around 66cm and 74cm respectively based upon reconstructions of their very fragmented bronze facings.¹⁶⁰ However, in the case of the Dodona find, some 80 per cent of the shield is missing and the remaining fragment is quite buckled. Similarly, in the case of the larger Vegora find, more of the centre of the shield has survived but the amount of remaining shield rim is almost the same as for the Dodona find. Thus, any calculation of shield diameter based upon these two fragmentary sections can only be regarded as estimates. Interestingly, Liampi stated that the estimated diameter of the Vegora shield was 66cm (the same diameter as the Dodona shield) in her 1990 article on the find, but then stated that the diameter was 73.6cm in her 1998 book on Macedonian shields.¹⁶¹ Hammond states that ‘the diameter of the [Vegora] shield cannot be determined precisely’ but agrees with Tarn that ‘there can be no doubt that his [i.e. Asclepiodotus’] measurements were in terms of Macedonian ‘feet’ and ‘cubits’’.¹⁶² However, Hammond then goes on to reexamine the size of Macedonian units of measure, based upon the size of the various stylistic elements of the Vegora shield, to conclude that the Macedonian foot was 32cm (which would result in a Macedonian cubit of 48cm – a point Hammond failed to realise) and that the shield would have had a diameter of 66cm (as per Liampi’s first estimate) when complete.¹⁶³

A more accurate indication of the size of the phalangite’s shield comes in the form of a complete limestone mould used to create the metallic coverings for the shields of phalangites in a Ptolemaic army (c.300BC) now in the Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam (Plate 6). The diameter of this mould measures 69-70cm.¹⁶⁴ However, it would create a covering large enough to have its outer edges (as indicated by the first ridgeline in the mould running around its circumference which is about 2cm, or one late-Attic daktylos, in from the outer edge) folded over the wooden core of a shield around 65cm in diameter. The covering of a Hellenistic shield found at Pergamon similarly measured around 65 cm in diameter.¹⁶⁵

The average size of the phalangite shield is given by Everson as between 65cm and 75cm.¹⁶⁶ Other scholars, basing their calculations on the early-Attic cubit of 45cm and Asclepiodotus’ reference to the shield’s diameter, state that the average size of the peltē was only 60cm.¹⁶⁷ However, the archaeological evidence clearly suggests that the shield was slightly larger than this. Using 65cm as the average, each of the two ‘feet’ of its diameter described by Asclepiodotus would therefore be around 32cm long and each daktylos about 2.0cm – the same as the Olympic/Peloponnesian/late-Attic standard that became the common unit of measurement throughout the Greek world in the last half of the fifth century BC.¹⁶⁸ Thus, as Hammond suggests, Asclepiodotus (and additionally Aelian) are clearly basing their writings on a larger ‘Macedonian’ cubit of 48cm and not one of 33cm as is suggested by Tarn – which is actually closer to the length of the Olympic/Peloponnesian/late-Attic ‘foot’.¹⁶⁹