Both the lengthy sarissa and the small peltē shield were the hallmarks of the Hellenistic man-at-arms.¹ The characteristics and encumbrance of these pieces of offensive and defensive armament dictate how they could be wielded and, more than any other element of the panoply, how the phalangite had to position his body to engage in combat. The positioning of the body would, in turn, influence how effectively the sarissa could be wielded, and how well protected the phalangite was by his shield – thus determining the effectiveness of any combative posture used to employ them.

Markle states that in order to understand the changes in military tactics brought about by the creation of the pike, ‘it is necessary to be clear about the limitations of the size and weight of the sarissa, since these factors determined how the weapon could be wielded in battle’.² However, while the design of the sarissa played a definite part in how the phalangite functioned on the battlefield, the pike was only one element of his panoply. In order to fully comprehend how the equipment carried by the phalangite influenced his performance on the field of battle, the limitations of all of the elements of the panoply combined must be considered.

Regardless of the time-period in question, and regardless of the method of fighting that is to be employed, there are certain fundamental criteria that need to be met in order for any combative posture to be effective. For the Hellenistic phalangite, armed with a lengthy pike and small shield, any combative posture must:

| a) | Allow the shield to be positioned in such a way so that it could be used defensively; |

| b) | Allow the phalangite to move on the battlefield without any restrictions, particularly in a forward direction; |

| c) | Provide stable footing to enable the phalangite to remain upright during the rigours of close combat; |

| d) | Allow the phalangite to maintain his position within the confines of the phalanx and conform to any limitations of space dictated by that formation; and, most importantly |

| e) | Allow the sarissa to be positioned in such a way so that the arms had a natural range of movement enabling the phalangite to engage an opponent offensively. |

The natural location for a shield to be positioned when in a combat situation is across the front of the body – there is literally no point in carrying a heavy piece of defensive equipment like a shield into battle if it is not going to be used to help protect the person carrying it. Unfortunately the ancient sources provide few details of how the phalangite positioned his body in order to place the shield in its most effective position for battle.

Some scholars suggest that in order to carry the weighty sarissa, the phalangite had to stand in a side-on posture with both feet facing forward (Fig. 10).³

Fig. 10: The position of the body and feet of a phalangite in a side-on position.

However, a side-on posture only satisfies some of the criteria necessary for an effective combative posture. Defensively, standing side-on in this manner does place the shield in a protective position – albeit a very limited one.

Standing side-on also creates the smallest target profile of the upper body, and places many of the vital organs at the furthest distance from any attack delivered from the front while the shield provides protection against any attack coming from the bearer’s front-left and, to a limited extent, from directly ahead. However, the body is completely open to attacks delivered from the bearer’s front-right which, due to the way in which the left hand is used to help wield the pike, leaves the phalangite with no means of altering the position of his shield in order to meet or deflect such attacks.

The diagrams accompanying Connolly’s discussion of the phalanx also depict the shields with the lower rim extended.⁴ For such a position to be achieved, the left elbow would have to be raised and the arm rotated outwards. However, as the left hand is used to help wield the sarissa, this contorts the arms and places a lot of stress on the muscles. Additionally, as the arm is raised, if the ochane was not appropriately shortened each time the arm was rotated and elevated in such a manner, the shoulder-strap would relax and no longer be supporting the weight of the shield or the pike. It is doubtful that anyone would be able to carry a shafted weapon weighing more than 5kg in this position for anything more than a few minutes. It is further unlikely that the shield would be positioned in this manner during combat as any strike made against the shield would be deflected dangerously upwards towards the bearer’s head. This suggests that an angled position, with the lower rim extended outwards, was not the standard placement for the phalangite’s shield.

In the suggested side-on stance, the left arm is extended outwards, akimbo to the body, and is relatively straight. Due to the use of a central armband and hand grip to help carry the shield, the axis of the shield must therefore follow the axis of the forearm which, in this case, results in the shield being positioned at an angle towards the left-rear (see Fig. 10 above). A shield placed in this position does cover the bearer from just below the shoulder to just above the left knee; however, due to the angle of the shield and the near full extension of the left arm, it is difficult to brace the shield in position using outward pressure exerted using the left thigh.

A shield which is unsupported in this manner is liable to injure the person carrying it when in a combat situation. A shield supported solely by a shoulder strap yet mounted on the forearm held in such a way has nothing bracing it in place. Any strike made against the top of the shield would cause it to rotate on the arm, potentially forcing the rim of the shield to impact with the upper arm or, depending upon how high the shield was being carried, the bearer’s face. Even if the shield did not impact with the bearer’s head, the new angle that the shield had been pushed into would allow for the enemy weapon which caused it to move (for example the sarissa of an opposing phalangite) to simply slide upward into the bearer’s face. The development and use of more open-face styles of helmet like the conical pilos would suggest that the phalangite shield was never used in a way which would endanger the bearer’s head either directly or indirectly and as such the shield cannot have been positioned in a way that would result in such dangers.

Due to the presence of the ochane, any strike which hit the bottom of the shield would not alter the angle of the shield too much, or push the rim into the bearer’s thigh to cause an impact injury, as the shoulder-strap would be pulled taut by the slight rotation of the shield caused by the impact which would then prevent it from being rotated any further. However, the positioning of the arm at such an angle as is required to adopt a side-on posture cannot be considered defensively stable and can therefore not be considered conformance with the first necessary criteria for an effective combative posture. This alone would suggest that it was unlikely that the phalangite used this posture to engage in combat.

The most likely posture that a phalangite adopted for battle is an oblique posture with the left foot forward, the feet well apart and the right foot back, and with the upper torso rotated to the right by approximately 45° (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: The position of the body and feet of a phalangite in an oblique position.

This is clearly the posture of the phalangites depicted on the bronze plaque from Pergamon – one of the few artistic representations of the phalangite in action (Plate 7) and the use of an oblique posture forms the basis of other modern models and illustrations of the phalanx in action.⁵

Defensively, positioning the left foot forward in the manner of the oblique posture causes the torso to rotate, or allows it to be easily rotated, so that the chest faces to the front-right. This presents the left shoulder forward which, in turn, allows the left upper arm to be held beside the body while the left forearm, supporting the shield, can be extended across the front of the body relatively parallel with the front of the space that the bearer occupies. Due to the need for the two hands that are used to wield the pike to be at least 70cm apart, the left forearm is held at a slight forward angle which causes the shield to extend towards the left-rear. However, this angle is only marginal and does not negatively affect the combat effectiveness of the posture (see following).

By positioning the body in an oblique posture with the left leg forward, the left thigh can be used to support the lower rim of the shield while, at the same time, the left shoulder can be used to brace the upper rim in position. This is made easier if the bearer bends forward slightly at the waist, something that cannot be done in the side-on posture, which not only lowers the shield slightly so that it is more easily supported by the leg, but also places the shoulder and the rest of the torso in a protective position behind the shield. Leaning slightly forward to carry the peltē is exactly how the phalangites are depicted on the Pergamon plaque and the resulting posture places the shield in a position where it covers the bearer from shoulder to knee (see Plate 7). Thus, unlike the positioning of the shield in the side-on posture, a shield held with the body in an oblique posture creates a very stable and well supported defensive position which an incoming strike would find difficult to move; and so attacks would not be dangerously deflected towards the bearer’s head. Furthermore, due to the slight concave shape of the peltē, even when the shield is held at a marginal angle as a result of the required spacing of the hands, the surface that is presented directly towards the front is still flat – which then creates the most effective surface for countering incoming attacks. This is an aspect of the shield’s positioning that does not occur in the side-on posture which, due to the more acute angle of the shield, can only present an angled surface to any attack which will simply cause it to deflect.

Standing obliquely does present a larger target profile of the body than a side-on posture. However, the vital organs are still angled away from any attack delivered from the front while a shield 64cm in diameter carried in this manner protects the bearer from the shoulder to just above the knee, in effect covering his entire torso behind the shield, while the lower limbs were protected by either greaves or high ‘Iphicratid’ boots and the head was protected by the helmet. In an oblique position the body is also better protected from any attack coming from the bearer’s right side. While not fully protected by the shield, the angle of the body, and the way that the left forearm is held across it, protects the bearer from most attacks coming in from anything less than a 45° angle from the front-right. The bearer would still be vulnerable to attacks coming from an angle greater than this – such as missile fire, infantry or cavalry attacks coming from the flank – but this is true of almost any combative posture. Based upon an examination of how the peltē could be positioned in both the side-on and oblique body postures, it is clear that the phalangite’s shield can only be used in an effective defensive manner when the body is rotated to the right by about 45°. This means that, of the two possible combative postures for wielding the sarissa, it is only the oblique position that conforms to the first necessary requirement for an effective combative posture.

As the pike-phalanx could be used both offensively and defensively, the ability to advance into battle was a vital aspect of the mechanics of phalangite warfare. This is clearly indicated by the battles of the wars of the Successor period. If the phalanx was completely immobile, and two opposing sides faced-off against each other but had no means of engaging, then the battle would simply not take place except through the use of other arms such as cavalry or light troops. However, not all of the possible ways for wielding the sarissa allow forward motion to be accomplished without impediment in conformance with the second necessary criteria for an effective combative posture.

Standing side-on, for example, greatly restricts the movement of the phalangite. While maintaining this position the ability to move forward is limited to a shuffling sidestep – basically the right (rearward) foot would need to be turned out and, with each step, brought up behind the forward left foot, before the left foot was then moved forward. If a more natural method of walking is employed, the body naturally rotates back to the left to provide the right leg with a freer range of movement. However, in doing so, the whole posture of the body changes from a side-on stance to an oblique position. Importantly, because the left arm is held outwards in the proposed side-on stance, moving the body into an oblique posture to facilitate movement also swings the left arm to the left – in turn causing the sarissa and the shield to swing to the left – which would then leave the phalangite vulnerable to a frontal attack. This indicates that such a method could not have been employed by the phalangite as, due to the massed confines of the phalanx, any weapon which moved in such a manner would swing into the space occupied by the man in front of him (except for those actually in the front ranks whose weapon would become entangled in those held by the file next to him).

While it is possible, although unlikely, that phalangites advanced into battle in this manner, it could not have been done rapidly. Nonetheless the ancient sources contain numerous references that the phalanx was capable of being more than a lumbering mass of extended pikes. Polyaenus states that Philip’s infantry made ‘a committed attack’ against the Athenians at Chaeronea in 338BC.⁶ At Gaugamela in 331BC, Alexander’s infantry line ‘rolled forward like a flood’.⁷ While both of these passages are not necessarily indicative of speed, the commitment of these attacks suggests they were done at something more than a slow shuffling pace. Clearer evidence for the phalanx’s use of speed comes from the description of the battle of Pydna in 168BC. Plutarch states that the Macedonian advance was so bold and swift that the Romans did not have time to move very far from their camp before the first man was slain.⁸ Thus it seems that the pike-phalanx had the ability to advance at a different pace depending upon the intentions of the commander and the tactical situation at the time.

However, it is almost impossible to move quickly with the body turned side-on and with the feet facing forward as the illustration of the side-on stance suggests. This is particularly so if the left arm is elevated and rotated to extend the lower rim of the shield (which suggests it was not done), and even more so if armour is being worn. Even the lighter linothorax with its pteruges greatly inhibits movement when the body is placed in this position due to the stiffness of the fabric. Furthermore, certain styles of helmet also restrict the movement of the head when a side-on posture is adopted. For a side-on stance to be adopted, the head has to be turned entirely to the left so that the phalangite can look directly ahead over his left shoulder to see any potential targets and to identify any obstacles or terrain that he would have to traverse. However, the elongated cheek pieces of the Thracian and Phrygian type of helmet that was used by some combatants in the Hellenistic Age sweep down below the jaw to provide additional protection to the neck and throat. When wearing either of these styles of helmet, it is impossible to fully rotate the head to the side as the cheek flanges come into contact with the chest or cuirass and inhibit further rotation – preventing the phalangite from looking directly ahead at the tip of his weapon and/or any opponent (Plate 12). While it is possible that this means that the Thracian and/or Phrygian-style helmets were not worn by phalangites as some scholars suggest, their depiction in Hellenistic art does indicate that they were used in conjunction with other styles like the Boeotian and the pilos.⁹ This, coupled with the fact that it is almost impossible to adopt a side-on position while wearing armour of any kind, suggests that the phalangite did not adopt a side-on posture to wield the sarissa.

Standing in an oblique posture, on the other hand, provides the phalangite with a full range of movement. As the body is only rotated by around 45°, any armour that is worn creates no impediment to forward motion or the position of the body. Forward movement, either at a walk, trot or even a run can be accomplished by simply walking/running forward in a natural motion. Importantly, such an action does not affect the wielding of the sarissa in a leveled position to engage in combat nor necessitate the removal of the shield from a protective position across the front of the body. The rotation of the head is also natural when an oblique body posture is adopted. As with the use of a side-on stance, the cheek pieces of the Thracian or Phrygian helmet still connect with the chest/cuirass when adopting an oblique body posture. However this occurs at the point when the head is facing forward and the gaze is directly ahead (Plate 12). This is due to the angled lower edge of the cheek piece on these helmets. Had these helmets possessed cheek pieces which did not have angled lower edges, but rather ones that were squared off, the ability to turn the head would have been similarly impeded. This suggests that the angular nature of the cheek pieces of both the Thracian and Phrygian-style helmets were conscious design considerations made in order to facilitate the oblique body posture needed to wield both the sarissa and the peltē correctly.

Firm and stable footing is a necessity in any form of hand-to-hand combat. This was fully understood within the context of the combat of the ancient world. The Archaic Greeks, for example, were advised to stand ‘firm set astride the ground’ (στηριχθεὶς ἐπὶ γῆς).¹⁰ The Roman writer Vegetius refers to a positioning of the body with a preferred foot ‘forward in combat’ depending upon which sort of weapon was being used.¹¹ This demonstrates that the Archaic Greeks and the later Romans well understood the importance of balance and correct footwork in combat. The professional armies of Hellenistic Macedon are unlikely to have been any different.

The ability to transfer the body’s centre of gravity and to provide stable footing is crucial to maintaining balance during the rigours of combat on terrain that might be soft, uneven or covered with the detritus of battle.¹² Arrian states that infantry ‘push with their shoulders and sides’ (τὁυς ὤμους και τὰς πλευρὰς αί ἐνεpείσεις).¹³ The term ἐνερείσεις (derived from the verb ἐπείδω) has several definitions including to push (with), thrust (with), lean in (with) or lay (upon). Regardless of which definition is used, it is clear that the terminology is meant to convey the idea that one side of the body is forward of the other. This could relate to a description of either a side-on or oblique body posture. However, an examination of how the body’s centre of gravity, and hence its balance, can be altered in either of these combative stances demonstrates that the oblique body posture is the most effective for engaging in hand-to-hand combat.

Standing side-on would allow a phalangite to brace himself into position to resist any strong impact against his shield. The rearward right leg, with the foot turned outwards, provides solid support for the body to resist any force exerted against the shield or body from the front. The side-on posture also allows the phalangite to exert his own counter-pressure against this force, or to deliver it against an opponent, by simply leaning towards the enemy and pushing using the strength of the right leg. However, a person in a side-on position has difficulty altering the body’s centre of gravity in every direction. By leaning either towards or away from an opponent, a phalangite could easily adapt his body posture in response to any pressure exerted against his shield. What a side-on position lacks is any ability to adjust the body’s position and centre of gravity to react to any pressure coming from the sides – such as jostling by the men in the files beside him, an attack from the flank, or even topographical influences – in order to remain upright. Diodorus, for example, states that the current of the Tigris was so strong that some of Alexander’s troops were swept to their deaths as they tried to cross it in 331BC because the force of the water ‘deprived them of their footing’ and the remaining troops were forced to link arms to avoid a similar fate.¹⁴ Some battles were fought across watercourses which had similarly strong currents such as at Granicus and Issus.¹⁵ The placement of the feet in the side-on position (which are basically in line with each other along the front-back axis of the posture) means that a phalangite could be easily knocked sideways due to the application of pressure from the side.¹⁶ If, on the other hand, the feet are separated left-right to provide more stable footing while manoeuvres such as river crossings are undertaken, this naturally alters the posture of the body into an oblique position.

Standing obliquely with the left foot forward and the feet shoulder width apart is the most effective position for the transference of body weight and the body’s centre of gravity. This is particularly so if the legs are slightly bent and the knee joints unlocked as this allows the phalangite to slightly squat and lean the body forward – which is required for him to gain the most protection from the small diameter of the peltē. Again, such aspects of combative posture are illustrated on the Pergamon plaque (Plate 7). Bending the knees both lowers and stabilizes the body’s centre of gravity and makes the posture more stable and more likely to be able to adapt to changing conditions and pressures. With the knees bent, the joints unlocked and the left shoulder presented towards the front, a phalangite would be able to easily lean towards an opponent to his front (just as Arrian describes) while being braced in position by the rearward right leg. The unlocked knees allow the legs to flex or compress and so absorb any pressure regardless of the direction from which it had come. The stability of this stance is enhanced further if the right foot is turned outwards while standing still – making a static line of phalangites very stable and adaptive to battlefield conditions. This ability to strengthen the position is not available to the side-on stance unless significant alterations to the posture as a whole are made. On the other hand, the oblique posture, even with the smallest stride distance between the feet, allows the phalangite to use the strength of their rear leg to press forward, brace themselves in position if needed, and move with stable and adaptive footing all at the same time. Subsequently, Arrian’s description of infantry pushing with their shoulders and sides is most likely a reference to the use of an oblique body posture with the left shoulder leading. Thus the physical dynamics of an efficient body posture correlates with the literary references and indicates that it was an oblique body posture that was used by the Hellenistic phalangite to bear his panoply in combat.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the body posture of the phalangite was that it needed to allow the individual to conform to the massed style of fighting that it was used in. The Hellenistic phalangite did not fight as an individual. Rather he was a part of the densely packed phalanx. Consequently, the phalangite’s body posture, and the way he wielded the sarissa, were not only dictated by how to most effectively carry this weapon, but also by the limitations placed upon the individual by all of those around him and the spacing of the formation that he was positioned within.

As noted earlier, the ancient writer Asclepiodotus outlines how infantry could be deployed in one of three orders: a close-order, with interlocked shields (synaspismos), with each man 1 cubit (48cm) from those around him on all sides (τὸ πυκνότατον, καθ’ ὃ συvησπικὼς ἕκαστος ἀπὸ τῶν ἄλλων πανταχόθεν διέστηκεν πηχυαῖον διάστημα); an intermediate-order (meson), also known as a ‘compact formation’ (puknosis), with each man separated by 2 cubits (96cm), on all sides (τό τε μέσον, ὅ καὶ πύκνωσιν ἐπονομάζουσιν, ᾧ διεστήκασι παvταχόθεν δύο πήχεις ἀπ’ ἀλλήλων); and an open-order (araiotaton) with each man separated by 4 cubits (192cm), by width and depth (τό τε ἀραιότατον, καθ’ ὃ ἀλλήλων ἀπέχουσι κατά τε μῆκος καὶ βάθoς ἕκαστoι πήχεις τέσσαρας).¹⁷

Yet not all of these were combative deployments. Asclepiodotus states that the open order was a ‘natural’ formation, while Aelian states that this deployment was only used when the situation called for it.¹⁸ What situation is not specified, but the openness of the formation would suggest that it was used primarily for marching as the troops were less likely to become entangled with each other, there would be less external threats requiring the adoption of a closer order, and there would be little need for the troops to remain in step. The intermediate-order formation is described as the general offensive deployment by Arrian and Polybius, and Asclepiodotus and Aelian both say that it was used to advance upon an enemy.¹⁹ The close-order formation with interlocked shields, on the other hand, is said to have possessed little offensive value for the pike-phalanx. Both Asclepiodotus and Aelian state that it was used to resist an enemy attack while Arian states that such a compressed formation limited the type of deployments that could be adopted (such as making an oblique line all but impossible).²⁰ Aelian also goes on to describe that one of the uses for the close-order formation was during the process of ‘wheeling’ the formation, as the more compressed nature of the close-order deployment meant that the troops had less distance to travel.²¹ Importantly, both Asclepiodotus and Aelian state that when this manoeuvre was undertaken, the weapons of the men in the formation had to be held vertically so as to not impede each other.²² This was also no doubt due to the fact that men carrying a shield with a diameter of 64cm, held across the body in a protective position in order to receive an enemy attack (as Asclepiodotus and Aelian put it) could create an interlocked shield wall, but due to the way in which the sarissa was wielded, made it impossible to position such a weapon for battle at the same time (see following).

Many modern models of Hellenistic warfare incorporate the use of phalangites deployed in an offensive close-order formation, in contradiction to the ancient manuals – although the terminology used in some of these models makes interpreting them somewhat confusing. McDonnell-Staff, for example, suggests that phalangites used a side-on stance so that they could stand in a 50cm space and that this resulted in a formation with interlocked shields (synaspismos)²³ Warry, who favours an oblique posture, also has phalangites creating a formation with ‘interlocked shields’ in close-order.²⁴ Snodgrass, who does not examine combative posture, offers that the synaspismos formation of 45cm per man (based upon the smaller Attic cubit of the early fifth century BC) was commonly used by Successor armies without detailing whether he thought it was (or was not) used by the armies of Philip II and Alexander the Great.²⁵ Sabin, in his modelling of ancient warfare, suggests that phalangites used various intervals in their formations (again based upon the smaller Attic cubit of 45cm and Asclepiodotus’ descriptions of formations) of between 45cm and 90cm per man.²⁶

The main problem with such models is that phalangites bearing a long pike and a shield 64cm in diameter are physically incapable of creating a combative formation with interlocked shields in an interval of only 45-50cm per man. Frontinus states that the phalanx did not like fighting in cramped conditions.²⁷ This suggests that phalangites required a certain amount of space in order to wield the sarissa effectively. Several ancient sources also detail how the pikes of the first five ranks of the phalanx projected between the files and ahead of the line.²⁸ As such, the minimum spacing between each file was not only limited by the amount of space that each individual man had to occupy, but it also had to leave enough room between the files themselves so that the weapons of the first five ranks could be lowered for battle.

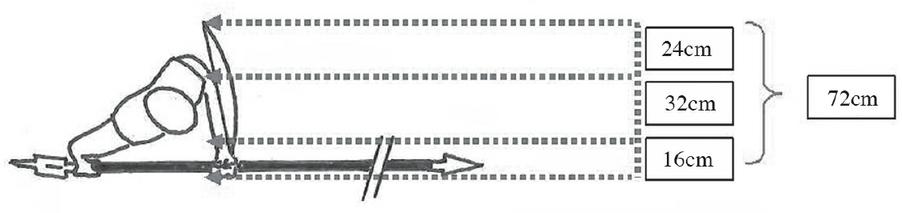

An average person with a height of about 170cm has a width across the shoulders of approximately 45cm. When adopting an oblique body posture to wield the sarissa, the amount of lateral (i.e. side-to-side) space that this person would take up would be around 32cm.²⁹ The extension of the right upper arm to wield the sarissa increases the required width of this interval by around 16cm – bringing a total lateral width just to cater for the body of the individual alone to 48cm (the same as the close-order interval detailed in the ancient literature). The right-hand edge of this interval would be delineated by the shaft of the sarissa which projected directly ahead of the person wielding it. Added to this, up to 24cm of the shield would project to the bearer’s left when he adopted an oblique body posture. Thus the minimum lateral interval occupied by a single phalangite adopting an oblique body posture, and with his weapon lowered for battle, was 72cm (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: The width of the interval taken up by a phalangite wielding the sarissa in an oblique body posture.

Smith calculates the horizontal space occupied by a phalangite in an oblique body posture with his shield held across his front as being between 78cm and 92cm.³⁰ Smith further claims that this allowed the other pikes, which he suggests were held at shoulder height, projecting over the shoulder of the man in front, to be deployed.³¹ However, it is unlikely that the weighty sarissa was carried at shoulder height. This means that there had to be enough room to the right side of the individual phalangite to cater for the presented pikes of the more rearward ranks (see following).

The projection of a section of the peltē to the left of the bearer would, if a weapon other than a sarissa held at waist level was being carried, allow a man to the left to move in, behind the bearer’s shield so as to create a close-order interlocking ‘shield wall’, just as Asclepiodotus describes it, similar to the way that the larger aspis allowed the Classical hoplite to create such a formation.³² Similarly, if the pike was raised vertically, phalangites would also be able to create an interlocking shield wall. However, the presence of this shield wall would then prevent the sarissa from being lowered for combat. This explains why both Asclepiodotus and Aelian state that the pikes had to be held vertically when this order of formation was adopted for manoeuvres such as ‘wheeling’ and demonstrates that such a deployment was not offensive or defensive (using the sarissa to hold an enemy back, for example) in nature.

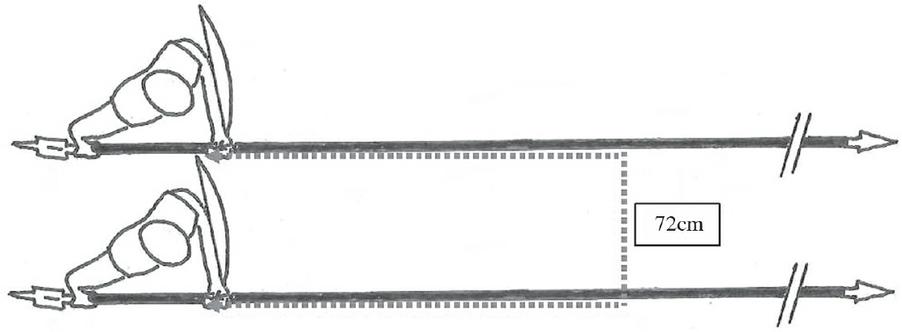

The difference between the shield-wall of the Classical hoplite and the shield wall of the phalangite is that Classical hoplites wielded their shorter spears with one hand and in an elevated manner which allowed the weapons to be positioned above the line of interlocking shields when poised for combat. The phalangite, on the other hand, wielded the sarissa with both hands at waist height which prevents a shield wall from being created at the same time. Due to the position of the shield on the left arm, and how the left hand is used to help wield the pike, the bulk of the shield sits at the same elevation as the sarissa when it is lowered for combat. Thus even two phalangites standing side-by-side would not be able to interlock their shields due to the presence of the weapon held by the man on the left. Consequently, the minimum distance between two phalangites positioned adjacently for battle is the distance from the sarissa carried by the man on the right, to the left hand edge of his peltē if his shield is abutted up against the shaft of the weapon carried by the man to the left – or a distance of some 72cm (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13: The minimum lateral spacing of two phalangites standing side-by-side.

In the image on the Pergamon plaque, the shields of the two adjacent phalangites are not overlapping and the shaft of the sarissa held by the rearward phalangite can be clearly seen extending between the two individual figures (see Plate 7).³³ This shows that these two individuals could not have been deployed with their shields interlocked and are most likely positioned in a formation no less than 72cm per man. This interval in itself is greater than the close-order formation outlined by Asclepiodotus and demonstrates that the pike-phalanx cannot have adopted a close-order formation for combat as some theories suggest.

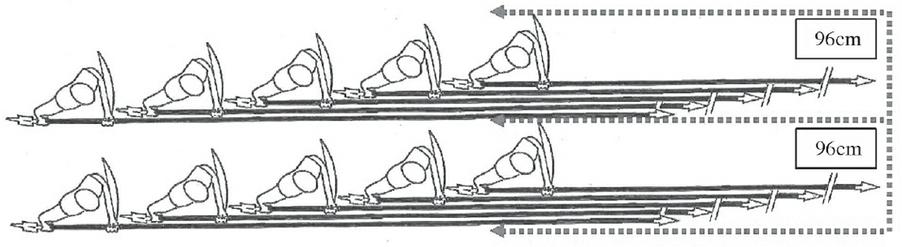

Further to this, the additional four pikes belonging to the ranks behind had to also be accommodated within the space between each file. Subsequently, the phalangites of each file had to be even further apart. Due to the weight of the sarissa, the weapon held by each subsequent rank could not have been elevated higher so that that it was positioned above the one held by the man in front (or over the shoulder of the man in front as is suggested by Smith or Hammond). The weapons could have only been deployed level and relatively parallel with each other and maintained in this position for the required (and undeterminable) amount of time needed for any engagement to play out. Plutarch states that the presented pikes of the Macedonian phalanx all sat at the same level and presented ‘a dense barricade’ to any opponent.³⁴ Such a reference can only mean that each pike was held at the same level as all the others. This means that, between each file, there had to be enough space to accommodate the physical characteristics of a total of five lowered pikes.

The sarissa had a shaft of around 3.5cm in diameter. However, it is unlikely that the weapons of each rank were hard pressed up against each other as this would simply jam the hands of the men carrying them between the weapons. A small amount of space had to have been afforded for the placement and dimensions of the hands in order to avoid any injury. Allowing 6cm of space per man for the thickness of the shaft of the sarissa, the fingers wrapped around it, and a small amount of room to move, four additional pikes would add another 24cm to the required interval between each file.³⁵ If this is added to the 72cm required for the man in the front rank, the total lateral space required between two files of phalangites, with the weapons of five ranks of men projecting between each file, is 96cm – the intermediate-order outlined by Asclepiodotus (Fig. 14).

Undoubtedly, the phalanx would not conform precisely to this interval all of the time. Gaps between the weapons of each man, for example, would open and compress through the simple movements of engaging in combat.³⁶ Additionally, it is unlikely that all five pikes belonging to each file were leveled exactly side-by-side. Due to variances in the height of each person, and movement of the formation over open ground, and the natural flex in the length of the sarissa, the pikes may have been positioned at slightly different elevations which varied over time. This would provide extra room between each weapon which would further reduce the risk of the hands becoming jammed between two adjacent weapons. Furthermore, as the men in ranks two to five were incapable of thrusting their weapon forward in an offensive manner due to the presence of the man in front of them, but would have merely held them in place, the men in these ranks could have stood slightly more erect than the man in the front rank (see: The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Sarissa from page 167). This would not only further reduce the risk of the hands of the man in the first rank becoming jammed between the other weapons of the file as he engaged in combat, but would also provide him with a small amount of additional room to undertake offensive actions without compromising the integrity of the formation. Yet despite any differences in the positioning of the weapons, the five presented pikes of each file would still only occupy a lateral space of about 24cm. What this understanding of the spatial requirements of the phalanx shows is that the minimum amount of room required for the formation to deploy for battle had to be the 96cm spacing of the intermediate-order at the very least.

Fig. 14: How the minimum interval for five phalangites deployed for battle is the intermediate-order of 96cm per man.

Some ancient writers employ terminology relating to a close-order formation in their descriptions of the phalanx in action. Arrian, for example, states that Alexander’s men adopted a synaspismos formation at the Hydaspes River in 326BC.³⁷ Plutarch also uses the term synaspismos in his descriptions of some Macedonian formations.³⁸ Some scholars have accepted these passages at face value – suggesting that the pike-phalanx used the close-order interval with interlocked shields.³⁹ English, on the other hand, recognizing that such a deployment is impossible for men armed with a sarissa and a peltē, suggests that the use of such terminology merely means the adoption of ‘as compact an order as possible’ and that such a formation required an interval of around 90cm per man.⁴⁰ This is undoubtedly correct due to the limitations of the phalanx. This is not a literary motif exclusive to Arrian and Plutarch, but the use of similar terms is found in the works of other ancient writers as well.

Curtius, for example, uses the term testudo three times in his account of the campaigns of Alexander to describe closely packed Greek and Macedonian formations. Tarn suggests that Curtius is using a piece of contemporary Roman terminology and placing it in an anachronistic context by ascribing it to the Greeks.⁴¹ However, the true context of the terminology is dependent upon an understanding of the passages it is being used in. The testudo was a Roman defensive formation created by each legionary moving close to the man beside him so that the rim of each shield (scutum) touched ‘edge-to-edge’ rather than overlapped. This presented a solid wall of shields towards any attack, particularly to thrown missiles.⁴² Members of the rear ranks of a testudo could also hold their shields above their heads and those of the men ahead them, in effect placing a roof over the formation to provide further protection. However, the important thing to note is that it was only the shields placed on the top of the formation which overlapped (usually just with those behind them which partially sat on top of the one in front) while those on the sides were abutted edge-to-edge. Thus the testudo was not entirely a formation with interlocked shields.

At 5.3.21, Curtius states that Alexander’s men, who were being showered with large stones and other missiles, found no protection in the adoption of a ‘tortoise formation’ (Nec stare ergo poterant nec niti, ne testudine quidam protegi, cum tantae molis onera porpellerent barbari). The terminology here is somewhat ambiguous. When attacked by large numbers of missiles, troops will bunch together for protection regardless of the configuration of shield they are carrying. As previously noted, it is unlikely that troops bearing the small Macedonian peltē would be able to create a formation with inter-locked shields unless their pikes were raised vertically – in which case they could either deploy in a close-order with interlocked shields, or in a bunched formation with the rims of their shields touching. Either case bears many similarities to different aspects of the Roman testudo formation with its abutted and over-lapping shields. At 5.3.23 the same troops withdraw with their shields ‘held above their heads’ (scutis super capita consertis). Any such formation, whether in close or intermediate order, would justify the use of the term testudo by Curtius to describe it for a contemporary Roman audience. At 7.9.3, Curtius states that while crossing the Jaxartes River, some of Alexander’s men adopted a ‘tortoise formation with their shields’ (scutorum testudine) to protect the oarsmen who were otherwise unarmoured. It is unlikely that this use of the word testudo is meant to be taken as a row of inter-locked shields in this instance. It is more likely that the term is here cognate with the use of a shield to provide protection, much in the way that the Roman legionary was protected behind his shield when in the testudo formation. The oarsmen on the vessel would have been seated some distance apart and it is further unlikely that shields held to cover them would overlap. It is possible that the spacing between each man was enough to allow the rims of each shield to just touch (as in the testudo formation of the Roman legionary) and this may account for Curtius’ use of the term. Thus Curtius’ use of the term testudo to describe Greek formations is not as anachronistic as Tarn suggests, but is the use of a contemporary simile to convey to an audience how the shields borne by the phalangites were positioned.⁴³

The inability for phalangites to adopt a close-order formation also demonstrates that Diodorus’ reference to Philip adopting the use of a close-order formation with inter-locked shields (synaspismos), in emulation of the Greeks at Troy, cannot be interpreted as the creation of the pike-phalanx (see page 34). Diodorus is clearly not using the term synaspismos in a more general manner to merely mean a closely ordered formation as he specifically states that the formation has interlocked shields. He is clearly describing the 48cm close-order formation of the manuals. Consequently, Philip’s reform to the Macedonian phalanx could only have been accomplished by troops who were armed in a way which would allow them to use such a formation – Greek hoplites.⁴⁴ Hammond suggests that the use of the smaller peltē allowed phalangites to create an even closer order than that used by Greek hoplites.⁴⁵ This is clearly incorrect from an offensive perspective based upon the spatial requirements of the pike-phalanx.

A comprehension of the minimum amount of space required for the phalanx to deploy also highlights the deficiencies in the proposed side-on stance for wielding the sarissa. If a man turns side-on to wield the pike, the width of his body from shoulder to shoulder, the extended right arm, and the akimbo left arm, take up an interval, front-to-back, of about 96cm – the same size as the intermediate-order interval and twice as large as the close-order interval.⁴⁶ Thus by adopting this posture, a phalangite would be incapable of adopting the very deployment which forms the basis for many examinations of phalangite warfare.

Connolly gets around this problem by suggesting that a close-order formation, with the phalangites using a side-on stance, was 96cm front-to-back and 45cm side-to-side.⁴⁷ Similarly English, citing passages of Aelian (11) and Diodorus (17.57.5) suggests that the ‘compact order’ was 1 cubit per man left-to-right and 2 cubits front-to-back to accommodate the grip, which must assume the adoption of a side-on posture as per Connolly, and that such a formation was used offensively.⁴⁸ This passage highlights the problematic nature of many examinations of the Hellenistic pike-phalanx. Firstly, the ‘compact order’, as English calls it, was another name for the intermediate-order of 96cm per man according to Asclepiodotus. It is unlikely such a term could be applied to any formation employing the close-order 48cm interval, even if only left-to-right, as English suggests. Additionally, Asclepiodotus and the other military writers clearly state that the intervals they are describing are the same size both left-to-right and front-to-back. Thus any model of phalangite warfare which suggests a difference between the lateral distance across the file to the distance front-to-back cannot be correct.

Hammond states that the pikes of the first five ranks were presented when the formation was arranged in a ‘close order’.⁴⁹ Again there are issues with such claims. If by ‘close order’ Hammond means the interval of 45-50cm per man, then this statement cannot be considered correct as it is impossible for the pikes of the phalanx to be deployed in such a way while in such a compressed formation and any claim to the contrary goes against what is outlined in the ancient literature. Polybius himself states that it was the ‘compact’ (i.e. intermediate) order formation of 2 cubits per man which allowed the pikes of the first five ranks to be presented.⁵⁰ Additionally, even if it is assumed that phalangites could somehow adopt a 45-50cm interval and still lower their weapons, a pike 576cm in length would be able to project ahead of the line even from the ninth rank so long as sufficient lateral space to accommodate all of the levelled weapons was provided. In this interpretation, it can only be assumed that, while it would be possible for the first nine ranks of the phalanx to present their weapons for combat, for some reason only the first five actually did so. Alternatively, if by ‘close order’ Hammond is actually referring to the intermediate-order of 96cm per man outlined in the manuals, then this statement would be correct in regards to the number of pikes that could be presented per file, but the terminology used to describe the interval is incorrect.

Furthermore, while Asclepiodotus and Aelian state that the close-order formation was not used offensively but could be used for ‘wheeling’ with the pikes held vertically, according to both writers the close-order could also be used to receive an enemy attack.⁵¹ Due to the physical requirements of the pike-phalanx, this passage can be interpreted in one of two ways. Firstly, if seen as a reference to a pike-phalanx, it must be automatically assumed that the phalangites would have been standing in an ‘attention’ (προσεχέτω) position with the sarissa raised vertically. This suggests that, if this is the case, the enemy attack that is being referred to is incoming missile fire against a static pike-phalanx, where the phalangite could use his left arm, which is not holding the pike while in this position, to raise the shield to protect himself, rather than an attack delivered by infantry or cavalry which would require the deployment of the pikes in order to repel it (which cannot be done in close-order).⁵² This then finds parallels in Curtius’ first use of the term testudo to describe a contingent of phalangites under missile fire. Alternatively, Aelian may be referring to a close-order shield wall of troops armed as Greek hoplites who can act offensively while maintaining an interlocking shield-wall.⁵³ Importantly, either interpretation cannot be taken as an offensive use of the close-order formation by phalangites.⁵⁴

Other scholars base their examinations of Hellenistic warfare on the intermediate-order interval of around 96cm per man. Champion, for example, states that Pyrrhus’ 6-7,000 man frontage at the battle of Asculum in 280BC covered a distance of around 7km.⁵⁵ This must assume an interval of around 1m per man deployed in an intermediate-order. However, in many of these examinations, the terminology used is often confused and/or erroneous and it is uncertain as to whether some of the proponents of these models have explicitly understood the consequences of such statements in relation to the broader understanding of the dynamics of phalangite combat.

Warry, for example, while using the oblique body posture in his examination, still has phalangites adopt what is labelled as a ‘close-order’ and then an even closer order with ‘locked shields’.⁵⁶ There are several problems with how this possible formation is presented. Firstly, Warry’s ‘close-order’ seems to be the intermediate-order of 96cm per man. English similarly says that phalangites occupied 2 cubits per man in ‘close-order’ which can also only be seen as a misinterpretation of the ancient literature.⁵⁷ Secondly, in the depiction of the formation with ‘locked shields’ given by Warry, the shields are neither ‘interlocked’, nor are they even ‘brought together’, which are the two ways in which the word synaspismos can be translated. This lack of inter-locking shields, and therefore a lack of conformance with the terminology used to describe the close-order formation, also occurs in any model which incorporates the use of a side-on posture to wield the sarissa due to the way that the shield is angled towards the left-rear – further indicating that this posture was probably never used. Finally, in both of Warry’s depictions of the ‘close-order’ and the ‘locked shields’ formation, the pikes belonging to the more rearward ranks are passing either above or below the shields of the men in the forward ranks (it is difficult to tell which from the diagrams). Regardless, due to the position of the shield and the weight of the sarissa, a deployment of rearward pikes either above or below the shield of the man in front is almost physically impossible.

Gabriel states that the ‘compact order’ (pyknosis) is 2 cubits of 45cm each (or 90cm total) per man, while the close-order (synaspismos) is 45cm per man and was used to engage in combat.⁵⁸ While the terminology used in these statements correlates with that of Asclepiodotus, the size of the cubit is based upon the earlier Attic standard incorporating a 45cm cubit rather than the Hellenistic standard with its 48cm cubit and contradicts Aelian’s statement that phalangites could not use a close-order formation offensively.⁵⁹ Despite such statements, Gabriel later states, similar to Champion, that a 20,000 man force, deployed to a depth of ten deep, would create a frontage covering 2km.⁶⁰ This again must assume the use of the intermediate-order of around 1m per man.

An understanding of the spatial requirements of the phalanx formation also demonstrates that Polybius is unlikely to be correct in his description of the sarissa being held by the rear 4 cubits of the shaft.⁶¹ If the weapon is held by the last 2 cubits as per the descriptions of Arrian, Aelian and Asclepiodotus, when deployed in an intermediate-order, the butt-spike of any weapon held is automatically pressed into the shield of the man standing directly behind (see Figs. 6 and 14). Thus a man in a rearward rank can get no closer to the man in front of him than the point where both his shield and the butt-spike of the man in front of him meet. Heckel and Jones suggest that greaves were a mandatory element of the phalangite’s panoply, particularly for those in the middle and rear ranks, due to the potential danger of receiving wounds to the legs from the butts of the weapons held by the men in the front ranks.⁶² However, as the butt-spike pointed toward the shield of the man behind, rather than towards the legs, there is little danger to the lower limbs. The level at which the sarissa was held would additionally allow the man in the rearward rank to press his shield into the spike of the weapon in front and so brace it into position. This is also another reason why the side-on posture is unlikely to have been used as, due to the acute angle in which the shield is carried when using such a posture, the butt of a weapon held by a man in a forward rank would point at the abdomen of the man behind – which would run a risk of inflicting accidental injuries during battle.

Importantly for the understanding of the deployment of the phalanx, when employing a 2 cubit grip on the weapon, having the man in a rearward rank press his shield into the butt of the weapon in front equates to each man occupying a space of 96cm – in accordance with the descriptions of the intermediate-order formation. However, if there was an additional 2 cubits of the weapon projecting rearward as per Polybius, then the distance between each man would have to be 4 cubits (i.e. the distance from the weapon bearer’s leading left hand to the point behind him where the spike of the sarissa connected with the rearward man’s shield). Thus, at least front-to-back, phalangites wielding weapons in such a manner could only deploy in an open-order formation of 4 cubits (192cm) per man front-to-back at best. Some scholars who favour the Polybian model get around this problem by having the extra 2 cubits of pike project under the shield of the man behind, or have the men slightly offset to accommodate the rear of the pike.⁶³ However, due to the position and elevation of the shield, this is a physical impossibility unless it is assumed that the men in the forward ranks have their weapons angled upwards so that the rearward sections can pass under the shields of the men behind. However, this would mean that they would then not be able to be lowered to engage in combat. Connolly notes how it has been suggested that the large butt on the sarissa could pose a threat to the men in the rank behind but then goes on to say that, by holding the weapon at the 4 cubit mark as per Polybius, the pike actually passes beyond the man directly behind.⁶⁴ What Connolly seems to have failed to consider is that this then means that the butt would be pointing directly at the man two ranks behind rather than the man immediately behind. Regardless, due to the position of the shield, this concept of a 4 cubit point of grip on the sarissa seems incorrect.

An understanding of the spatial requirements of both the phalanx as a whole, and that to wield the sarissa, also shows that Tarn’s proposed smaller, 33cm, Macedonian cubit cannot be correct (see the previous section on the Length of the Sarissa from page 66). Regardless of the configuration of the weapon used, it is physically impossible for the men of the phalanx to occupy a space only 66cm square in an intermediate-order deployment based upon this unit of measure and still adopt an effective combative posture. In his reconstructive experiments, Connolly found it impossible to march a unit of phalangites forward when deployed in an interval less than 69cm per man.⁶⁵

Thus we are left with two options for interpreting the description of holding the sarissa by Polybius. Either the passage itself is incorrect (whether this was the fault of Polybius himself, his sources, or later transcription is unknown), or that Polybius is correct, but in accepting this it must also be accepted tha pike-phalanxes in the second century BC only fought using an open-order deployment of 4 cubits per man for which there is no evidence. Either way, any modern theory which examines Hellenistic warfare based solely on the description of Polybius needs to be appropriately revised.

By examining the spatial dynamics and requirements of the phalanx as a whole, it can be seen that an oblique body posture was required for the phalangite to effectively bear and wield his panoply. The side-on stance simply occupies too much room to conform with the descriptions of the phalanx found in the ancient literature and places the phalangite in a position where he may be accidentally injured by the man in front during the trials of combat. The oblique posture, on the other hand, not only conforms to the spatial requirements of the phalanx (when a weapon with a point of balance 2 cubits from the rearward end is used), but also allows the phalangite to retain his shield in a protective position across the front of his body which, by pressing it into the butt-spike on a weapon held by the man in front, not only braces that weapon in position, but actually indicates to the rearward man that he is positioned properly within an intermediate-order interval. All of these elements would come in to play simultaneously to create a formation that was stable, protected, and conformed to the needs of the phalanx.

One of the most important aspects of any combative posture is the ability to act offensively. Yet by its very nature, the offensive abilities of a phalangite within a phalanx were greatly restricted. Indeed, anyone other than the members of the front ranks would not have been able to thrust their weapon forward into an attack at all. This was due to how both hands were used to wield the sarissa, how the shield was strapped to the left forearm at the same time, and how that shield was pressed into the butt-spike on the pike held by the man in a more forward rank when conforming to an intermediate-order deployment. Thus not only did pressing the shield into the butt-spike ahead of you brace that weapon in position, but in a negative capacity, it prevented you from performing any offensive action with the sarissa at the same time. It was only the experienced officers of the front ranks of the phalanx who were not similarly impeded and were thus capable of undertaking offensive actions directly to their front. The members of the rear ranks could engage an opponent with their weapons, but this was only under certain battlefield conditions (see The Anvil in Action from page 374). Yet even in these instances, body posture dictated how effectively the sarissa could be used.

If a side-on body posture is adopted, the position of the body greatly restricts any movement of the weapon. Any attacking motion has to swing the arms from right to left as the sarissa is thrust forward. However, in doing so the right upper arm almost immediately impacts with the upper body and so limits the amount that the weapon can be moved. The construction of the shoulder joint itself also restricts the amount of movement across the body that the right arm can make. Additionally, the presence of rigid shoulder sections on any armour worn further impedes the movement of the arms in this position (see: The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Sarissa from page 167). Consequently, it seems unlikely that such a posture was used to wield the sarissa in combat.

By standing obliquely, on the other hand, the right shoulder is not restricted in its range of motion. The angled position of the body creates a gap between the torso and the upper arm (see Fig. 14). The ball and socket construction of the shoulder joint is also not impeded as any thrusting motion does not have to pass across the body, but the weapon (and arms) can simply be pushed/swung forward. The angle of the body also negates any impediment on the motion of the arms which might be caused by the shoulder sections of the armour when using another posture. Rather the angle of the body, the gap between the right arm and the torso, and the lack of restriction by the cuirass, provide the phalangite with a full range of motion for both arms with which to engage an opponent effectively.

The following table (Table 7) summarises the required criteria that any stance a phalangite could adopt must satisfy in order to be considered an effective combative posture and how the two suggested techniques (the side-on and the oblique positions) either conform, or not, to these requirements:

| Criteria | Side-on Stance | Oblique Stance |

| Allow the shield to be positioned in such a way that it could be used defensively. | No | Yes |

| Allow the phalangite to move on the battlefield without any restrictions, particularly in a forward direction. | No | Yes |

| Provide stable footing to enable the phalangite to remain upright during the rigours of close combat. | No | Yes |

| Allowed the phalangite to maintain his position within the confines of the phalanx and conform to any limitations of space dictated by that formation. | No | Yes |

| Allow the sarissa to be positioned in such a way that the arms had a natural range of movement so that the phalangite could engage an opponent offensively. | No | Yes |

Table 7: A summary of the necessary criteria for an effective phalangite combative posture per stance.

As can be seen, it is only by positioning the body at an oblique angle that a phalangite is able to satisfy all of the necessary criteria for an effective combative posture. The understanding of the use of such a posture to carry the phalangite’s equipment into battle further influences all subsequent examinations into how the sarissa could be wielded and its effects – both in terms of the reach and trajectory of any attack made with it, how the weapon’s position could be altered, and every other fundamental aspect of engaging in combat with a pike in the Hellenistic Age.