In order for the decisive hammer stroke of the flank attack to be successful, the pike-phalanx, acting as the anvil, had to be able to effectively engage the centre of an enemy formation and pin it in place. This was where the fighting style, deployment and equipment peculiar to the Hellenistic phalangite came into play. Polybius flatly states that the pike-phalanx was far superior to the formations used in Greece and Asia in the earlier parts of the Hellenistic Period.¹

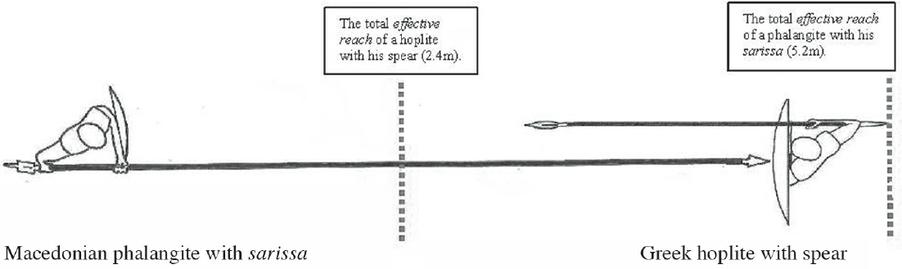

Depending upon the type of opponent the pike-phalanx was facing, the phalangites within the units of the formation could operate in a number of ways to achieve the objectives of the overall battle plan. If the opponents were heavily armoured, such as Greek hoplites or Roman legionaries, then all the phalanx had to do to effectively pin them in place was to hold them at bay with the tips of their sarissae. This is exactly what the Macedonians did at the battle of Pydna in 168BC according to Plutarch.² In this position the phalangites were relatively secure. Greek hoplites had a combat reach of around 2.4m with their spears.³ This is far shorter than even the amount that the shortest sarissa projects ahead of the man wielding it. Consequently, Greek hoplites could not even reach an opposing phalangite with their weapons unless they managed to somehow get ‘inside’ the first few rows of projected pikes. Yet Polybius says that this was all but impossible even for a Roman legionary carrying a shield that was thinner than the Greek aspis and wielding the small gladius instead of a lengthy spear.⁴ Furthermore, when a phalangite and an opposing hoplite are in this position, the phalangite in the front rank has not even made an attacking move with his weapon and has another 48cm of effective reach with which to try and dispatch his opponent if an opportunity to deliver a killing blow presented itself (Fig. 56).

Fig. 56: The difference in effective reach between a phalangite and a hoplite.

This brings into question Polybius’ statement (18.29) that the sarissa was held by the last 4 cubits of its length. If the purpose of such a lengthy weapon was to provide greater reach so that enemies could be engaged at a safe distance, it would seem illogical that it would be designed in a way that the weapon’s point of balance meant that a third of its length was behind the person wielding it rather than projecting ahead of him. Most hand-held weapons such as swords, daggers and, in particular, the spear used by the Greek hoplite, are all configured with a point of balance towards the rearward end of the weapon where the hand grasps it so that the person wielding it can use the length of the weapon to its full advantage. The sarissa, developed from the hoplite doru, is unlikely to have been any different and Polybius’ statement is most likely incorrect (see pages 83-88).

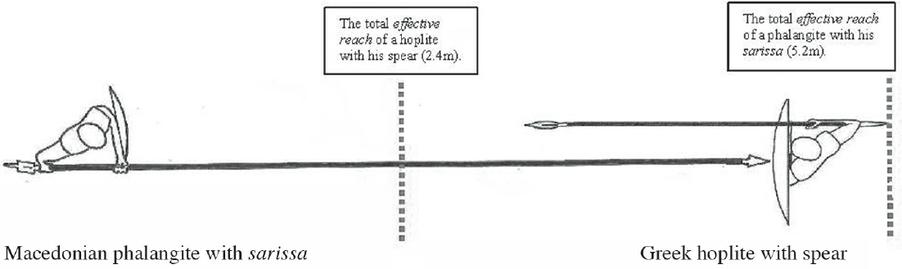

Greek hoplites, for the most part, also fought in the intermediate-order employed by the Macedonian pike-phalanx.⁵ This meant that each hoplite across the front rank of a Greek formation would face five pikes levelled at him by the opposing Macedonians (Fig. 57).

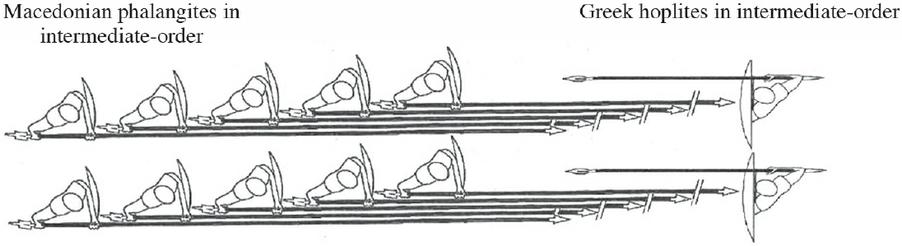

Even if the Greeks constructed a close-order shield wall using an interval of only 48cm per man, a formation commonly used by well trained troops like the Spartans, two Greeks would still face the five pikes presented by each file of the Macedonian phalanx. Additionally, the interlocked nature of the closer formation meant that, despite two hoplites facing each file of phalangites, individual hoplites would be unable to try and move between the sets of sarissae to engage the phalangites at closer quarters as they were locked into the formation (Fig. 58).

Fig. 57: How Greek hoplites in intermediate-order face five sarissae of the phalanx.

Fig. 58: How two Greek hoplites in close-order face five sarissae of the phalanx.

Thus no matter what order of interval an enemy formation of hoplites adopted, the members of the pike-phalanx were well protected behind their wall of serried pikes and were able to engage an opponent at a greater distance than the enemy could. This made the pike-phalanx practically unbeatable in a front-on confrontation – a sentiment specifically stated in many of the ancient texts.

Despite such limitations, opponents like Greek hoplites could mount a strong resistance to the Macedonian phalanx. The Theban Sacred Band, for example, is said to have been able to hold their ground against the Macedonians at the battle of Chaeronea in 338BC and that, following the battle, Philip found them all dead to a man where they had stood.⁶ At the Granicus in 334BC, the hoplite mercenaries fighting on the Persian side are said to have inflicted great losses among the Macedonians as they were fighting at close quarters.⁷ How are such accounts to be interpreted? How were hoplites able to resist an assault on their position which, as Diodorus states for Chaeronea, caused bodies to pile up until Alexander was finally able to break their line? There are several ways that such descriptions can be interpreted. Firstly, the members of the Sacred Band may have been able to withstand the attacks of the phalangites simply through the use of their larger shields. The Macedonians may have pressed the tips of their pikes into the Greek shields to keep them at bay and something of a stalemate could have ensued as the front rank phalangites sought to drive the Theban hoplites back or exploit targets of opportunity. It must be noted, however, that such a resistance by the Sacred Band would not include offensive actions against the Macedonians who would have been out of reach. Thus their resistance would have been wholly defensive and totally one sided. Alternatively, it must also be considered that such accounts may simply be literary motifs to both emphasize the ability of the hoplites and, by default, glorify the Macedonians who defeated them. Finally, it has also been suggested that Alexander led a unit of cavalry against the Thebans at Chaeronea rather than pike-wielding infantry.⁸ Plutarch states that the Thebans had faced troops carrying the sarissa.⁹ However, Plutarch may be referring to the long cavalry lance rather than the infantry weapon. If this is the case, then the Sacred Band did not face phalangites at all and may have been able to mount a stronger, and partially offensive, resistance to cavalry. If, on the other hand, the Sacred Band were engaged by pike infantry, then their deaths can only have been the result of thrusts delivered by the members of the front rank of the pike-phalanx. Due to the difficulty in committing such attacks against opponents with such large shields and strong defensive armour, this would account for the difficulty the Macedonians seem to have had in defeating the hoplites of the Sacred Band – with the lengthy sarissa eventually being the deciding factor.

Even if the Sacred Band itself did not face Macedonian phalangites at Chaeronea, the remainder of the Athenian and Theban line certainly did. Macedonian victory at other parts of the line seems to have been more easily obtained, partially through Philip’s use of a feigned retreat on his right wing, than in the confrontation with the Sacred Band. This not only highlights the difference between the experienced members of the Sacred Band and the other hoplites of the part-time citizen militia of Athens and Thebes, but would also correlate with the account of the stand of the Sacred Band as a literary motif to emphasize the fact. Despite any strong stand against the Macedonians at Chaeronea, the Greek hoplite was greatly outclassed by phalangites wielding a lengthy pike when both sides engaged frontally. At the Granicus, Alexander’s phalangites were able to easily overcome contingents of mercenary hoplites fighting for the Persians, while at Issus mercenary hoplites were only able to partially resist the advance of the pike-phalanx with the aid of an elevated position on the river bank.

Sekunda suggests that the shorter pike of the Iphicratean peltast was created to counter the spears of the Greek hoplite.¹⁰ Such a development of military weaponry would certainly make sense. Prior to the Iphicratean reforms, the Greek hoplite had dominated the battlefields of the ancient world. The most effective way to overcome such troops, armed with a long thrusting spear, would have been to engage them with a longer one, and this is the essence of pike-based combat – to outreach your opponent. This, in part, explains why, when more engagements against the Macedonians were imminent during the wars of the Successors, many city states of Greece abandoned the use of hoplites in favour of the adoption of the sarissa and the rest of the phalangite panoply.

A need to outclass the Greek hoplite also explains the greater depth of the Macedonian phalanx. The traditional hoplite deployment was eight deep – although formations of greater and lesser depths were also used.¹¹ Thus even the ten deep dekads of the Macedonian army in the time of Philip II, and later the sixteen deep syntagmae of the army of Alexander, were deeper than, and in some cases double the depth of, a hoplite formation. Not only would this provide a considerable amount of reserves to the Macedonian line (even though, due to the advantages of the pike-phalanx, they may not have really been needed), but such a deep formation would impart a strong psychological deterrent to anyone facing it, was mutually supporting due to its sub-units, and the depth provided momentum and encouragement to those within it. Had the Macedonians regularly deployed in half-files of eight (or even of five), on the other hand, then any psychological bonus provided by the pike-phalanx would be lost and its advantage would solely lay with the length of its weapons.

Unlike the Greek hoplite, the Persian forces faced by Alexander in the late fourth century BC fought in a completely different manner. Whereas the Greek hoplite was designed for massed, frontal, hand-to-hand, combat, the Persian way of war relied more on masses of cavalry, and their infantry were much more lightly armoured (if at all), were more mobile, and often relied on skirmishing, hit-and-run tactics, and using missile weapons to hit their enemy from a distance while relying on weight of numbers.¹² Thus the more lightly-armoured Persians were at a distinct disadvantage when fighting the Macedonians. Africanus states that ‘face-to-face with [Macedonians], no barbarian would be able to stand firm, no matter how he was fitted out’.¹³ Following the Persian defeat at Issus, Darius increased the length of the swords and lances that the Persians used as he considered that the Macedonians held a distinct advantage in the reach over their weaponry.¹⁴ This shows that Macedonian success was in part due to the length of the sarissa.

The configuration of the phalangite panoply provided other benefits to massed combat. The adoption of the hammer and anvil tactic to use the pike-phalanx to simply pin an opposing formation in place meant that a lowered pike, supported by the ochane and the oblique posture adopted to wield it, could be held in this position for a considerable length of time without causing the phalangite to become fatigued due to the minimal amount of thrusting offensive actions which would/could be undertaken. Thus the experienced officers in the front rank could maintain their position at the ‘cutting edge’ of the pike-phalanx and would not need to be rotated to the rear of the formation (a move that is almost impossible due to the mass of lowered weapons extending between the files) due to muscular exhaustion. The ability to hold back an opponent with a shorter reach weapon would have also reduced the risk of those in the front ranks sustaining injuries – another reason why such men would need to be moved to the rear, but one that would be difficult to accomplish once the phalangites in the front ranks had the tips of their weapons pressed into the shield of an opponent.

Despite its advantages, engaging lightly-armoured opponents with a pike-phalanx also presented potential problems – especially if that opponent charged against the line of phalangites en masse. At the battle of Gaugamela, the Persians are said to have attacked ‘all along the line’ which suggests just such a massed charge.¹⁵ What then happened when the two lines met? The accounts of the battle of Gaugamela (or other similar encounters) unfortunately do not go into such detail. However, the possible outcomes can be worked out with the understanding of the dynamics of fighting in the pike-phalanx.

When a wall of serried pikes met a mass of lightly-armoured opponents charging at it, one of two things would have happened – mostly likely concurrently along different parts of the line. If, on the one hand, the shields carried by the lightly-armoured opponent were able to resist penetration by the presented sarissae, then the opponent would be brought to an abrupt halt, those advancing behind him would slam into his back as the lines compressed, and the man in the front rank would be held back by the sheer length of the weapon pressed into it. As such, the two sides would remain ‘at pike length’ from each other and the phalanx could continue to keep the enemy at bay until a flanking attack could be delivered.

On the other hand, if the shields carried by the lighter troops could not stand up to the points of the sarissae (or if they did not carry a shield at all), or if the impact of the more rearward ranks of the charging formation slamming into those in front of them as they were brought to an abrupt halt by the weapons of the phalanx, applied pressure to the front ranks and drove them forward, the very impetus of the charge could result in many of the lightly armoured opponents impaling themselves on the pikes of the phalanx. While this would have undoubtedly caused significant casualties among the front ranks of the charging enemy, it would have had dire consequences for the members of the pike-phalanx as well.

If the momentum of a charge impaled an opponent on the tip of a sarissa this would effectively take that weapon out of action. Due to the pressure being exerted from the compressing ranks of the charging enemy formation, and the bracing in place of the front rank pikes by the men of the second rank of the phalanx, any phalangite who found an enemy pierced by his pike would have no means of retracting that weapon to continue fighting. The impaled body, falling to the ground, would take the tip of the pike with it. This would open up a small, but potentially dangerous gap in the ‘serried wall of pikes’. The next row of the charging enemy formation, carried forward by their own momentum over the bodies of those who had fallen, could also find themselves impaled on the sarissae of the second rank of the pike-phalanx with similar results. Thus, by the time the first three to four rows of the enemy had been slain, most of the pikes projecting ahead of the formation could have been rendered useless and, due to many of the members of the front ranks retaining their positions while the members of the more rearward ranks were unable to commit their weapons for action due to the depth of the file, the front-rank phalangites would have had little recourse but to drop their pikes and engage at much closer quarters with swords. When this occurred, the pike-phalanx would lose much of the advantage that the lengthy sarissa was designed to provide. This could have been one way of neutralizing the effectiveness of the phalanx – although, in terms of manpower, it would be a very costly one.

Such a compounding series of events would also occur if the sarissa was regularly used to thrust at an enemy. If the weapon became lodged in the body of an opponent due to the delivery of a killing blow, the pike would similarly become useless unless that killing blow was delivered in the furthest half of the weapon’s combat reach which would then provide the phalangite with enough room to extract it and continue fighting.

Prior to the engagement at Gaugamela, Alexander is said to have instructed Parmenion to order his troops to shave, stating: ‘do you not know that in battle there is nothing handier to grasp than a beard.’¹⁶ Such passages suggest that Alexander recognized that his front lines may have become overwhelmed if the more lightly armoured Persians chose to charge his position and that the fighting could ‘devolve’ into something more ‘in your face’ (almost literally). Plutarch similarly claims that phalangite combat was fought ‘amid shields, pikes, battle-cries and the clash of arms’.¹⁷ This again suggests how frantic some pike engagements could become – although it does not necessarily mean that all of them resulted in the pikes becoming unserviceable. This suggests that the primary function of the sarissa was for it to be pressed into an opponent’s shield in order to keep him at bay rather than to be used as an offensive weapon except when targets of opportunity presented themselves.

This primary use of the sarissa as a pushing weapon also correlates with the concept that the sarissa came in two parts. It needs to be considered, if the sarissa was in two sections, why an opponent simply did not pull the front end off and make the weapon ineffective? The answer is that the nature of phalanx combat rarely created the conditions where such a thing was possible. Most opponents facing a pike-phalanx would be carrying a shield in their left hand and a weapon in their right. Thus the only way an enemy could actually grasp the front end of the sarissa would be if they somehow freed their right hand. This would be difficult, although not impossible for a Greek hoplite wielding a long thrusting spear – who could raise the weapon vertically and transfer it to their left hand while their shield remained carried by its central armband. It would be somewhat easier for troops such as Roman legionaries armed with a sword which could be put back in its scabbard. However, this could only be done after the legionaries had cast the pila during the opening stages of the confrontations as, unlike the hoplite aspis, the Roman scutum, with its single grip and lack of central armband, was carried in a manner which prevented the left hand from being used for anything other than porting the shield. Plutarch’s statement that the Romans tried to grasp the Macedonian pikes in their hands at the battle of Pydna not only suggests that they were trying to separate the front end of the weapon from the back, but also that their swords were sheathed and their javelins had been cast in order for this to even be attempted.¹⁸ When engaged against another pike-phalanx, such as during the wars of the Successors, no one would have had the ability to grab onto an opponent’s sarissa due to the way that both hands were required to carry the weighty weapon.

Even if an opponent managed to get himself into a position to grab onto the pike, it was not guaranteed that this would render the weapon ineffective. At the battle of Edessa (c.300BC), for example, the Spartan king Cleonymus ordered the first two ranks of his troops to deploy without weapons so that they could grab onto the opposing sarissae while others swept around them to carry on the fight.¹⁹ This indicates that just grabbing the pike alone would not take it out of action. Indeed, the nature of massed combat would make it almost impossible for such an opponent to detach the front half of the pike. If the pike-phalanx was itself advancing, the forward momentum of this movement would drive the tip of the pike into an opponent (either his shield or body) with a result that anyone holding onto the pike would be simultaneously pushed back, the lines of his formation would compress, and he would not have sufficient room to step backwards and pull the front off the sarissa. Similarly, if the opposing formation was advancing against a static phalanx, once the tip of the pike was pressed into the opponent’s shield, the forward impetus of his own lines would also compress the formation and limit his ability to separate the two halves of the sarissa. This suggests that, at Pydna, both sides were somewhat static or moving only slowly – despite Plutarch’s statement that the initial Macedonian advance was conducted quickly.²⁰ Even if the two lines were only marginally separated, if a grasping opponent possessed enough room to step back and try to dislodge the front end of the sarissa, all the phalangite had to do was to thrust the weapon forward into the shield of the opponent, to negate this action and prevent the separation from happening.

Additionally, any force being brought to bear against the tip of the sarissa would force the two halves of the sarissa together within the connecting tube. This would make it even harder for someone to try and separate the two halves. Furthermore, in order to gain enough grip and leverage on the shaft of a sarissa that was pressed into his shield to pull it apart, an opponent who had grasped the weapon would have needed to turn his body and use his body mass behind his pull on the shaft. Doing so would result in the opponent exposing a side of his body to the other pikes of the phalanx. This would place the opponent at considerable risk and seems an unlikely practice except in the most extreme circumstances. This again means that the conditions where an opponent could attempt to pull the front end off a sarissa on the battlefield would have been rare.

The only time where the sarissa would have been at risk of separating would have been if the phalangite had delivered an offensive blow at some distance within the effective range of the weapon and the tip somehow became stuck in the opponent. If this occurred, when the phalangite tried to retract the weapon, the rear half which he was holding may dislodge from the forward half if it was securely lodged in the enemy’s body and the grip of the connecting tube on the shaft was not sufficient. This partially explains why the diameter of the connecting tube is slightly smaller than the diameter of the shaft – the elasticity of the metal provided the tube with more grip on the weapon. This additionally suggests that the primary function of the sarissa was to be pressed into an opponent’s shield, where it would not easily become lodged, in order to keep that opponent at a safe distance. In turn, the very nature of phalangite combat suggests that a sarissa that came in two sections was not only possible, but would have been just as effective as one with a single solid shaft.

When confronted by cavalry, chariots and even elephants, the pike-phalanx faced a similar dilemma. If the momentum of the beast did not simply snap the sarissa at the moment of impact, or force it backwards injuring the man in the rank behind, the tip of the pike could become lodged in the body of the animal. To counter such threats, the units of the phalanx may have moved out of their way rather than engage them directly. At Gaugamela, Darius sent hundreds of scythe-bearing chariots at Alexander’s phalanx in an attempt to disrupt the formation.²¹ Both Arrian and Diodorus state that to counter this attack the Macedonians opened their lines to allow the chariots to pass through into a ‘killing zone’ behind them.²² Connolly suggests that this opening of the lines was conducted by having whole syntagmae move to the right into new positions behind adjacent units.²³ While this would create a sixteen metre wide opening for the chariots to charge into as Connolly notes, it seems unlikely that such a manoeuvre could be undertaken. In order to effectively draw the Persian chariots into these gaps, they would have to appear almost instantaneously otherwise the drivers would simply change their course and direct their vehicles at a different part of the Macedonian line where they could inflict casualties. Even if the members of the syntagmae were still holding their pikes vertically, rather than presenting them lowered to engage the chariots directly, it would still take considerable time to move a unit the size of the syntagma out of the way of a charging chariot and to a new position behind the front line.

This makes the moving of entire units to create gaps to counter a chariot attack unlikely.²⁴ The ancient texts do contain references to a pike-phalanx ‘opening its files’to create gaps for lightly armed skirmishers to retreat through. However, this is more likely the moving of the members of alternate files into the intervals of the neighbouring file (in effect taking it from intermediate order to close order front-to-back). To undertake such a movement would also require the phalangites to have their pikes raised vertically. Appian describes how the pike-phalanx of Antiochus at Thermopylae in 191BC opened its files to allow skirmishers to withdraw, the formation then reformed into an intermediate order (puknon) and then, once in position, lowered their pikes for battle.²⁵ This shows that the normal deployment for battle was the intermediate order, that the opening of the files had to therefore be a move into a close order, and that the pikes were held in a vertical position until the intermediate order formation was re-established. ‘Opening’ into a close order by having every alternate file merge with the one to its right would create 48cm gaps between each file which skirmishers could pass down before the files resumed their original positions. However, these gaps would not be large enough to accommodate a charging chariot. Curtius, interestingly, makes no mention of this opening of the lines at Gaugamela and states that the pike-phalanx stood its ground looking ‘like a rampart…creating an unbroken line of spears’.²⁶ This would suggest that the phalanx did not divide itself but engaged any chariots that made their way through the screening units of skirmishers positioned ahead of them.

Lucian’s reference to the Thracians going down on one knee to brace a lengthy pike in position to engage cavalry raises the possibility that Alexander’s front ranks did something similar at Gaugamela.²⁷ However, Curtius’ statement that the phalanx created an ‘unbroken line of spears’ seems to more closely fit with their standard arrangement of standing upright with the pikes of the first five ranks lowered.²⁸ If this was how the pike-phalanx met Darius’ chariots at Gaugamela, then it seems safe to assume that the collision of the horses and chariots with the line of infantry would have caused some sarissae to snap, others to be forced out of the hands of the men wielding them, and others to impale the charging horses. This would have caused great disruption to the line – an effective, but costly, tactic.

As if to confirm such events, the narratives state that on the left wing, Parmenion’s troops suffered badly due to cavalry assaults.²⁹ We are not told whether the beleaguered troops in question were cavalry, pike-infantry, or both, but Parmenion was in overall command of the entire left wing, including units of the pike-phalanx, and the all-out attack by the Persians suggests that troops of both types were pressed hard – although Parmenion does save the situation with his Thessalian cavalry. If the Persian cavalry did attack the pike units on the Macedonian left then, as would have happened in the centre, much of the phalanx may have been disrupted by the mounted charge which greatly diminished the integrity of the line.

The other thing to consider is whether cavalry or chariot drivers would even attack a formation bristling with extended pikes. In 479BC at the battle of Plataea, a contingent of Phocian hoplites adopted a close-order formation to resist a charge by Persian cavalry. This formation would have also presented a wall of extending spears. Recognising the strength of this formation, Herodotus tells us the Persian cavalry turned and withdrew rather than engage.³⁰ Africanus also states that hoplites could easily repulse an attack of cavalry ‘with their spears’.³¹ It seems that, if the mounted Persian troops at Gaugamela had possessed a clear view of what they were charging at, they would have similarly not engaged a pike-phalanx with a frontal assault. Diodorus says that there was a great amount of dust being kicked up on the plain of Gaugamela and that Darius used this dust to hide his escape.³² If this dust was blowing into the ‘no man’s land’ between the lines at Gaugamela – i.e. the wind was blowing the dust towards the Persians and away from the Macedonians – as Diodorus’ account of Darius using it to screen his movements would suggest, then it is possible that the Persian chariots and cavalry may not have even seen what they were charging at until it was too late to alter their course. Additionally, such impaired vision would make it unlikely that the units of the pike-phalanx would have had enough time to open their lines to create gaps to allow the chariots to pass through (as suggested by Arrian and Diodorus), and they would have more likely engaged the mounted troops directly as they emerged charging from the dust – which would then correlate with the account of Curtius.³³ Heckel, Willekes and Wrightson suggest that the ‘lane’ that the Persian cavalry charged into at Gaugamela was actually the gap that had formed in the phalanx by the separation of the units of Meleager and Simmias and that Arrian (or his sources) was using Xenophon’s account of the battle of Cunaxa to account for how the Persians had managed to get their mounted troops through the phalanx.³⁴ If this is the case then the ‘lanes’ were not actually created but were ‘accidental’. It also seems that, if the line could be maintained, the pike-phalanx could hold its own against a mounted charge and may have even been terrifying enough (if clearly visible) to force one to back down.

At the Hydaspes in 326BC, Alexander’s army faced contingents of chariots as well as elephants – the first time they had fully engaged such beasts.³⁵ Unlike at Gaugamela, the terrain at the Hydaspes is reported to have been muddy due to a recent downpour and so there would have been little dust impeding anyone’s vision.³⁶ In the opening engagement, Alexander’s troops, after crossing the river, were attacked by advance units of the Indian army which included a contingent of chariots.³⁷ Supposedly recounting a record of the battle written by Alexander himself, Plutarch states that Alexander expected to be attacked by Indian cavalry.³⁸ Arrian states that one of Alexander’s intentions was to fight a delaying action against this force with his own cavalry to allow his infantry to move up.³⁹ This would suggest that Alexander thought that his infantry would be able to effectively engage whatever units Porus sent against him. Yet most of this advance guard of the Indian army was taken out using cavalry and skirmishers rather than the pike-phalanx.⁴⁰

For the main engagement, Porus had positioned both elephants and chariots across the front of his line.⁴¹ The phalanx was ordered not to advance into action until the enemy wings had been disrupted (another example of the timing requirements of the use of the hammer and anvil tactic).⁴² According to Curtius, despite the trumpeting of the elephants unsettling the members of the pike-phalanx, the beasts seem not to have troubled Alexander. The king is said to have claimed ‘our spears are long and sturdy; they can never serve us better than against these elephants and their drivers – dislodge the drivers and slay the beasts’.⁴³ This would suggest that Alexander believed that the pike-phalanx could effectively engage such animals. Plutarch, on the other hand, states that Alexander recognized the threat of the Indian elephants and so chose to mount a flank attack against the enemy using his cavalry.⁴⁴

Alexander’s flank attacks are said to have taken out most of the Indian chariots and the phalanx then advanced in the centre.⁴⁵ Reports vary as to how, if at all, the pike-phalanx engaged the elephants. Diodorus says the phalangites only engaged the units of Indian infantry positioned between the beasts.⁴⁶ Other reports state that as the phalanx advanced, the elephants were the targets of attacks by skirmishers who showered the animals with missiles and, when they got close, hacked at their legs and trunks with axes and swords.⁴⁷ Curtius says that the whole phalanx (by which he means the entire infantry line) succeeded in punching through the Indian forces in a single advance – which must have involved some direct confrontation between the pike-phalanx and the elephants.⁴⁸ Regardless of which account is accepted, it seems clear that Alexander’s pike-phalanx could, at least partially, hold its own against cavalry, chariots and even elephants.

For the most part, cavalry is used to either attack other cavalry or to deliver flank attacks against enemy infantry (as per the actions at Gaugamela and the Hydaspes). Rarely is the pike-phalanx used to counter an attack by mounted troops. Despite this, Aelian’s military manual contains a number of chapters devoted to the different type of cavalry formations that could be used against the pike-phalanx and the various infantry formations that are best employed to counter them.⁴⁹ Importantly, all of the formations detailed by Aelian would require substantial time to adopt and could not have been done on the spur of the moment. Aelian also does not describe opening the files as a tactic that could be employed to counter mounted troops or chariots. This suggests that the chariot charge at Gaugamela was screened by the dust that had been kicked up on the battlefield and, therefore, the pike-phalanx probably did engage, and resist, them directly (as per Curtius) as both sides would have had little time to react.

The capacity for the pike-phalanx to easily resist a cavalry charge seems confirmed when the use of cavalry in the age of the Successors is examined. Snodgrass outlines how the ratio of infantry to cavalry greatly increased from the time of Alexander to the Age of the Successors, providing the following figures as examples (Table 19):

| Period/Encounter | Ratio of Infantry to Cavalry |

| Age of Alexander | 2:1 |

| Battle of Sellasia (222BC) | Antigonus Doson – 8:1 |

| Battle of Raphia (217BC) | Antiochus - 5:1 Ptolemy IV - 5-10:1 |

| Battle of Cynoscephalae (197BC) | Philip V - 8:1 |

Table 19: Examples of the ratio of infantry to cavalry in the times of Alexander and the Successors.⁵⁰

The reduction in the reliance upon cavalry is a clear demonstration of changes in the type of opponent that was being fought from the time of Alexander into the time of the Successors. During Alexander’s conquest of Asia, the Persian and Indian forces that his army primarily engaged were strong in cavalry and, while numerous in infantry, that infantry was not armed in a manner which made them effective against the pike-phalanx. Consequently, using the pike-phalanx to both engage an opponent and pin their centre in place while the strong contingents of Macedonian cavalry struck the flanks was a sound tactic.

However, by the time of the Successors, the main infantry opponent was another pike-phalanx rather than enemies wielding short reach weapons such as those Alexander had faced. Thus the fundamentals of strategy, and the composition of armies, seem to have changed. Had the pike-phalanx been unable to stand up to cavalry, one would expect to see a decrease, rather than an increase, in the ratio of infantry to cavalry within Hellenistic armies. Instead, the amount of cavalry declines. This suggests that cavalry was not considered to be an effective force for use against an opposing contingent of pikemen except when attacking them from the flank.

Rather than solely rely on cavalry as the shock arm of an army, warfare in the Age of the Successors saw the development of other technologies for war to give one side an advantage on the battlefield. This accounts for the increase in the length of the sarissa from 12 cubits (576cm) in the time of Alexander to 16 cubits (768cm) at the end of the fourth century BC. If two pike-phalanxes were engaged against each other, with both carrying weapons of the same length, then neither side would hold an advantage over the other in terms of the reach of their combatants. Two forces equipped in such a way would simply pin each other in place and the outcome of the battle would rely more on the morale of the two sides, the depth of opposing formations (as per Sellasia), the success of any flanking attack, or the simple luck of the day. If, on the other hand, one side wielded lengthier weapons, that side would be able to both pin their opponent in place, and deliver killing blows if the opportunities presented themselves, while remaining outside of the range of the shorter weapons of their enemy, much in the same way that Philip’s phalanx held an advantage over Greek hoplites, or that of Alexander over the Persians.

Additionally, due to the way that both hands are employed to wield the sarissa, as the left arm extends as the weapon is thrust forward, the shield, strapped to the left forearm, is moved out of its defensive position across the front of the body. While this does not pose any threat when the phalangite is engaged against an opponent bearing a short-reach weapon like a sword or spear, it would place him at considerable risk when engaged against another pike-phalanx when both sides were bearing weapons of the same length. Such actions would have been very limited and only been undertaken when a certain killing blow could be delivered.

Furthermore, due to the way that the phalangite shield was securely mounted to the left forearm, and because both hands were employed to wield the sarissa, should a phalangite find his shield pinned in place by an opponent bearing a longer pike, that phalangite would have no way to thrust his weapon forward in an offensive manner even if an opportune target presented itself. In effect, using a longer pike and pressing its tip into the shield of an opposing phalangite rendered that enemy offensively impotent – incapable of any action like advancing or attacking – and would force him to simply stand his ground until he was slain either by a killing blow delivered by the longer weapons of the enemy, or mowed down by cavalry attacking from the flanks. This not only accounts for the increases in the length of the sarissa, but also highlights that the primary use of this weapon across the Hellenistic Age was to simply pin the opposing side in place.

Mounted troops were still a main strike weapon against pike-wielding phalangites during the wars of the Successors, as is demonstrated by the battles of Paraetacene, Gabiene, Gaza, Asculum, Raphia and Magnesia where cavalry were used to deliver flanking attacks against enemy formations. However, the changed nature of combat during this time meant that the opportunities where such attacks could be delivered were more limited, or had to be created in a different manner, to the ways they had been in the time of Alexander.

At battles such as Gaugamela and the Hydaspes, Alexander had used the oblique movements of his right wing of the cavalry to force part of the enemy (usually an opposing force of cavalry) to mirror his actions which resulted in the creation of an exploitable gap in the opposing line. The large, infantry-based armies of the Successor Period, on the other hand, were less likely to fragment in such a way due to their lesser mobility and, in many of the encounters of this time, the infantry line remains in place while cavalry are only used to initially engage other cavalry. Additionally, the traditional hammer and anvil tactics, and especially those employed by Alexander, would have been well known to most Hellenistic commanders of the age and any attempt to create a gap via an oblique advance of cavalry on either wing would have been anticipated. Consequently, in order to open gaps in the enemy line, other avenues of attack had to be employed. Thus there is an increase in the use of elephants in the Successor Period – whose charge was used to either smash an opposing wing and create a gap for cavalry to charge into (Gabiene, Raphia and Magnesia), to deliver sweeping attacks against the flank of an enemy line (Heraclea), or to make frontal charges against enemy infantry in an attempt to break the formation apart (Gaza, Ipsus and the ‘elephant victory’).

Julius Africans paints a vivid picture of the impact of a charge of elephants and the terror that this may cause:

…they make a terrifying spectacle at first sight: both to horses which are unaccustomed to them, and to men as well; and when [the enemy] equipped them with a tower, they considered them a source of fear, a sort of rampart advancing before the battle-line. Their trumpeting is piercing and their charge irresistible…It was…a multiple vision of military superiority: volleys of many missiles being cast from above by men with the advantage [of the tower], the area of the elephant’s feet being impregnable, and the enemy even fleeing far away. The battle was not one fought on an equal footing; against the elephant a siege operation would have to be conducted. When the front ranks were broken [by the elephants], as always happened, the troops turned and their ranks, shattered by the enemy, were primed for total destruction…Who could stand up to an avalanche from the collapse of a cliff-side? An elephant in combat makes the impression of a mountain: it overturns, it throws down, it smashes, it slaughters, and it does not spurn anyone who is lying in its way…It grabs horse, man and chariot with its trunk, strikes them violently, turns them upside down, and drags them to its own feet. By leaning on them with its knees, it squashes them – aware of its own weight – made even heavier by the addition of towers.⁵¹

The use of elephants in such ways created a new shock arm for many Hellenistic armies. Diodorus states that a contingent of elephants in the army of Polyperchon in 318BC had ‘a fighting spirit and a momentum of body that was irresistible’.⁵² One of the reasons given for why Alexander’s troops were reluctant to advance any further than the Hyphasis River in 326BC was the report that the kingdoms on the far side were said to have possessed thousands of elephants.⁵³ This demonstrates the impact that such beasts could have on the psyche of even seasoned professionals.

The threat of elephants thundering into infantry and breaking the formation apart seems to have been of considerable concern to some commanders who employed novel ways to counter the beasts. At Megalopolis in 318BC, Damis had wooden boards studded with sharp nails projecting upwards buried in shallow trenches near the entrance to the city. When the elephants of Polyperchon advanced into the breach, the animals stepped on the nails and, according to Diodorus, were in such pain that they could neither advance nor retreat while their drivers, and some of the beasts, were brought down by missiles fired from the flanks.⁵⁴ At Gaza in 312BC, Ptolemy deployed a series of spikes (χápαξ) chained together which were strung across the front of his right-wing infantry in the hope that these traps would foul any charge made by the opposing elephants of Demetrius.⁵⁵ This tactic worked. Diodorus describes how many of the beasts were wounded by treading on the spikes (he states that the softness of their feet is an elephant’s one true liability) and caused the attack to collapse in disorder.⁵⁶ Africanus similarly states that iron caltrops, when stepped upon, bring the elephant to a halt by penetrating into the soles of their feet.⁵⁷ At Asculum in 279BC, the Roman consul Publius Cornelius Mus employed a different method to counter enemy elephants: 300 ox-drawn ‘anti-elephant’ wagons. Dionysius of Halicarnassus describes these contraptions as being equipped with:

upright beams upon which were mounted movable traverse poles that could be swung round as quickly as thought in any direction that one may wish and, on the ends of these poles, there were either tridents or sword-like spikes or scythes – all of iron; or again they had cranes that hurled down heavy grappling-irons. Many of the poles had attached to them, projecting in front of the wagons, fire-bearing grapnels covered in tow that had been liberally smothered with pitch, which men standing on the wagons were to set fire to as soon as they came near the elephants and then rain blows with them upon the trunks and faces of the beasts. Furthermore, standing on the wagons, which were four-wheeled, were many light troops: bowmen, stone-throwers and slingers who threw iron caltrops…⁵⁸

These wagons initially held back the on-rush of the elephants as the battle began until both the oxen and the men controlling the wagons were brought down by light troops.⁵⁹ The use of such devices to inhibit an attack that would inflict the kind of carnage that Africanus describes showsjust how powerful the elephant arm of a Hellenistic army had become and also the dominant role that such animals played during the wars of the Successor Period.⁶⁰

While cavalry seems to have been relegated to a lesser role than it had before, its use in flanking attacks to try and drive the enemy from their position, once an exploitable gap had been created, ensured that they still held a valuable position on the battlefield. Regardless, almost all commanders of the Hellenistic Age still relied on a massive pike-phalanx as the basis for their army – the only formation which had the ability to stand up to opposing infantry armed in a similar manner.

However, when the pike-phalanx began to confront the legions of Rome in the third century BC it, yet again, faced an enemy who fought in a completely different style. The legionaries of the Roman Republic were able to put up strong resistance to, and even gain victories over, the Macedonian phalanx at battles such as Heraclea, Asculum, Cynoscephalae and Pydna.⁶¹ How this was accomplished was a matter of considerable examination even in ancient times. Polybius, for example, devotes a digressionary section of his histories to discussing how the Romans were able to overcome the pike-phalanx, while Africanus devotes a similarly sized section to comparing the armaments and fighting styles of the Greeks, Macedonians, Persians and Romans.

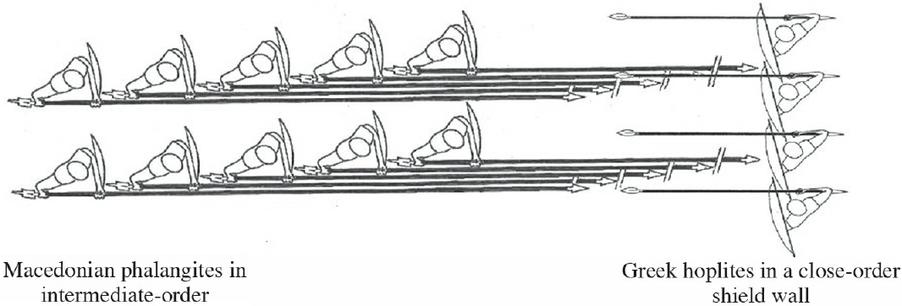

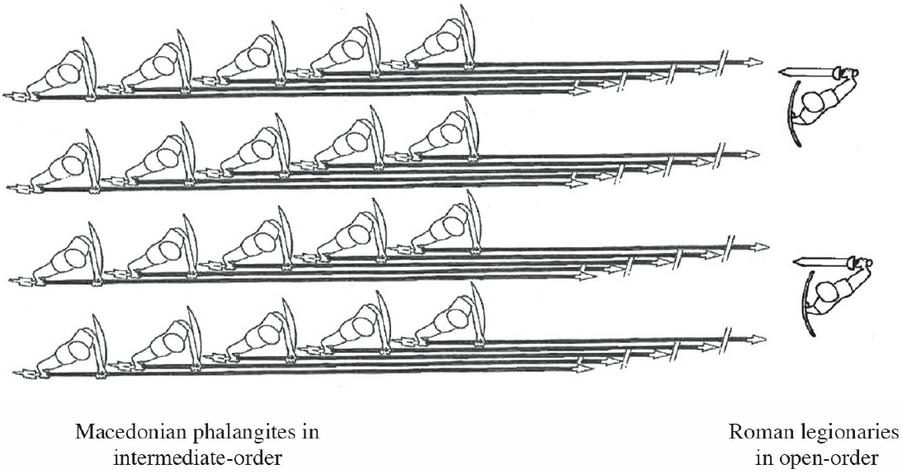

According to Polybius, the Romans formed their lines with an interval of three Greek feet (τρισί ποσὶ) of free space on either side of each man, and from front to back, in order to provide him with enough room to fight.⁶² Thus each space occupied by the Roman legionary was six Greek feet across. Each Greek foot equated to about 32cm; meaning that an interval of six Greek feet equalled 192cm – the same as the open order for phalangite formations detailed in the military manuals. As if in confirmation of this, Polybius goes on to state that when adopting this order of spacing, each Roman faced two files of the pike-phalanx (which each used the intermediate-order interval of 96cm per man) and, as a result of this difference in interval each legionary in the front rank of the Roman formation would have to face ten sarissae (Fig. 59).⁶³

Fig. 59: How Roman legionaries in open-order face ten sarissae of the phalanx.

The Roman legionary, armed with the short, gladius-type sword, had a far shorter effective reach due to the size of his weapon and, like both the Persians and the Greek hoplite, would have similarly been unable to reach an opposing phalangite when the sarissa was pressed into his shield – just as Plutarch says happened at the battle of Pydna.⁶⁴ How could such an open formation have ever stood a chance against the pike-phalanx?

At Heraclea and Asculum, Pyrrhus’ pike-phalanx gained costly victories over the legions of Rome.⁶⁵ The battles of Cynoscephalae and Pydna resulted in Roman victories – although these were close-run encounters. Indeed, Polybius remarks that some found it incredible that the pike-phalanx could be defeated at all (accounting for which became the purpose of the digression in his histories).⁶⁶

The advantage of the Roman legionary lay with his mobility and adaptability. According to Polybius, the Hellenistic phalangite was less suited to besieging enemy positions, being besieged, marching and encamping in open country and to meet unexpected attacks.⁶⁷ Similarly, Africanus states that legionaries:

have an advantage in agility, ready for both attacks and withdrawals, and they are swifter both in taking high ground and in the use of the sword… And they themselves are also trained in every technique of close-combat so that, in knowledge, both they and the Greeks are evenly matched, but in the lightness of their equipment they have the advantage.⁶⁸

Another area in which Polybius says the Roman legion was superior to the Hellenistic pike-phalanx was in its method of deployment. Polybius states that one way to defeat a pike-phalanx was to engage it with one part of your army while reserve units that had originally been posted behind the front lines could sweep around and either attack the phalanx from the side, or charge into gaps that had opened in the line.⁶⁹ This bears a close resemblance to the hammer and anvil tactics employed by Alexander and the Successors. The main difference is that in Polybius’ strategy both the frontal assault and the flanking attack are delivered by infantry as opposed to the infantry anvil and cavalry hammer of Hellenistic warfare. It was here that the mobility of the Roman legionary really came into play.

Such manoeuvres could not have been conducted by pike-infantry alone due to their cumbersome equipment. This explains why it was more mobile cavalry, and later elephants, which delivered decisive blows against enemy formations in Hellenistic warfare. The Roman legionary, on the other hand, was an allpurpose soldier – capable, as Polybius and Africanus state, of rapid movement in most directions. Livy claims that, where the Macedonian pike-phalanx lacked mobility and formed a single line, the Roman army was more elastic – being made up of numerous contingents – which could act individually or in concert as required.⁷⁰ However, it must be noted that, due to the use of units and subunits within the pike-phalanx, Livy’s claim is not entirely accurate.

Despite this apparent elasticity, in a frontal clash, the Roman legionary was hopelessly outclassed by the pike-phalanx. The long sarissae could be pressed into his shield which would keep him at bay with little offensive recourse at his disposal. Africanus additionally states that the Roman legionary shield (the scutum) was less effective in closed ranks as the soldier carrying it was unable to push against it with his shoulder due to the way that the grip was configured.⁷¹ Livy, on the other hand, states that the scutum provided better protection than the Macedonian peltē.⁷² The inability to exert counter pressure with the Roman scutum as noted by Africanus partially explains why Plutarch states that, at the battle of Pydna, the Romans could not break the Macedonian line head on, and that the Romans resorted to various means to render the pikes facing them unserviceable – including hacking at them with their swords, trying to push them with their shields, or grasping them in their hands.⁷³

What the Roman legionary needed was to get to closer quarters with his opponent, where his larger shield and short sword could be used to the most effect. Africanus’ statement that the necks of the Greeks were particularly vulnerable to Roman swords suggests that close-quarters battle was where the Roman legionary was in his element and that they regularly got close enough to an enemy to inflict such injuries.⁷⁴ Similarly, Livy’s reference to the Greek horror at the wounds inflicted by the gladius in 200BC highlight just how formidable a close-quarters weapon the Roman short sword was.⁷⁵

In order to be in a position to inflict such injuries, when facing a pike-phalanx, legionaries needed to attempt the removal of the sarissa from the combative equation (as they tried to do at Pydna) in order to get closer to their opponent, or to attack from the flanks or into gaps in the opposing formation (as Polybius suggests). Polybius additionally states that one of the advantages of the legionary was that he was also effective when fighting as an individual.⁷⁶ Africanus, on the other hand, states that no Roman soldier fights on his own.⁷⁷ While this initially seems contradictory to the statement made by Polybius, both claims can be reconciled in the ability of the Roman legionary, in close-quarters combat, to fight somewhat singularly while, at the same time, still being part of a unit.

Additionally if, due to the variables of combat, the opposing Roman and Macedonian formations aligned so that each legionary was directly opposite each alternate file of the pike-phalanx (in effect only facing five sarissae rather than ten) this still poses little problem to the legionaries, but could cause considerable trouble for the phalanx. Even though every second file of the pike-phalanx in this scenario would not have an opponent standing directly in front of it, these unopposed files could not continue to advance lest they move forward, between the legionaries, and into a position where they could be attacked at close quarters from the sides with little chance of retaliation, and while compromising the integrity of the phalanx as a whole at the same time. Thus every second file of the phalanx is essentially nullified by the Roman open-order without having to actually engage it. The Macedonian phalanx, on the other hand, could not adopt a similar open-order deployment so that each file of phalangites faced a single file of legionaries as this would create avenues in the lines which the more mobile Romans would have been able to exploit. Thus, no matter how the enemy was deployed, the security and integrity of the pike-phalanx lay in the adoption and maintenance of an intermediate-order spacing.

Consequently, by having the Romans fight in an open order which the pike-phalanx was not able to exploit, fewer Romans were placed in a position where they could potentially be killed by pike thrusts delivered by the front rank of the phalanx. This, in turn, meant that Roman formations could be wider, and have more men placed in reserve (just as Polybius advises) as they were not needed to hold the phalanx in place. Furthermore, by standing further apart, the Roman legionaries also had enough room to use their shield to parry or deflect the pikes they were facing into the vacant gaps between their files. This could also provide many of them with the opportunity to move inside the reach of the front rank weapons and then, using the same procedure, move further ahead to where they could attack the phalangites from a close distance – again, with little chance of retaliation. It is unlikely that the Romans adopted such an open formation when engaging against other more mobile opponents like Gauls or Germans, and Polybius’ reference to the open order of their deployment in his comparison to the Macedonian style of fighting must be something specifically undertaken by the Romans in order to negate many of the advantages of the pike-phalanx.

Another advantage that both Polybius and Africanus fail to comment on is that the Roman legionary also carried several javelins. Polybius himself, in an earlier section of his work, outlines how the members of the Roman infantry carried a light and heavy missile weapon (the pilum) some 3 cubits (144cm) in length.⁷⁸ Livy, who does mention the pilum in his comparison of the Roman and Macedonian fighting styles, claims that the javelin was ‘a much more effective weapon than the spear’.⁷⁹ As two opposing sides closed with one another, volleys of javelins would be launched from the Roman lines. The room required to cast such missiles also partially accounts for the openness of the Roman order of battle as described by Polybius. These missiles would slay many members of the opposing front ranks of an enemy formation like a pike-phalanx and, as the phalanx continued to advance over the bodies of their fallen comrades, the phalanx would begin to break apart just prior to any closer contact.

Such weapons would have dire consequences for an advancing pike-phalanx. Polybius states that the rear ranks of the phalanx held their pikes at an angle over the heads of the men in front to protect them from incoming missile fire.⁸⁰ However, this would only work against missiles such as arrows, fired on a high curving trajectory from a large distance, which would rain down and then become entangled in the angled pikes. Javelins, on the other hand, were cast at a much shorter range and on a much flatter trajectory. Consequently, the front ranks of the pike-phalanx were only protected by their shields and armour and, due to the weight of the sarissa which they were carrying in both hands, could not quickly or easily raise a shield to receive or deflect an incomingpilum. This meant that the front ranks of an advancing phalanx were particularly vulnerable to the main Roman missile weapon.

Many years after Polybius, Julius Caesar would comment on the effectiveness of the Roman javelin by stating that ‘…several of [the enemy’s] shields could be pierced and pinned together by a single pilum…’⁸¹ If this was as true in the Hellenistic Age as it was in 58BC when Caesar wrote this passage, then the members of the front rank of an advancing pike-phalanx, unable to deflect an incoming missile with their shield due to the other elements of their panoply, would have been considerably susceptible to injury or death from the opening volleys of Roman javelins. The removal of many of the front rank of the phalanx (where all of its experienced officers were positioned), and the partial disruption of the line caused by volleys of javelins, would have therefore ‘softened’ the phalanx and aided the Roman legion engaging with it. However, due to the depth of the phalanx, these volleys of missiles would not break the formation or destroy it completely and, by the time the javelins had found their mark, a hand-to-hand encounter between phalanx and legion was all but inevitable.

Skarmintzos suggests that the triumph of Rome over the Hellenistic pike-phalanx was more the result of Rome’s generals than the direct superiority of the legion and that Roman commanders adapted their tactics to overcome the advantages held by the phalangite.⁸² While partially true, these adapted tactics would not have been possible without the mobility of the legion as described by the likes of Polybius and Africanus. Tarn, on the other hand, blames the failure of the phalanx on its negligence to protect its flanks – a practice he says the Macedonians began to neglect during their pike-phalanx versus pike-phalanx encounters with the Spartans at the end of the third century BC.⁸³ Again, while partially correct, it was really only the mobility of the Roman legion which could exploit this, and other, vulnerable areas of the pike-phalanx.

When strengthened by a united front, and with its wings protected, the phalanx was almost unstoppable so long as the cohesion of the line was retained. The use of semi-independent units and sub-units meant that, rather than being a solid, rigid line, the pike-phalanx possessed a level of tactical flexibility and adaptability which allowed it to perform on almost any terrain. The formation’s weaknesses lie in its inability to turn and face new threats, the gaps that would invariably form in the line, and the inadequacy of the phalangite in individual combat should those gaps be exploited. It was this that ultimately led to the phalanx’s downfall. The utilisation of a strong but more mobile form of fighting saw many of the advantages of the pike-phalanx lost and witnessed the demise of the pike-phalanx from its place of dominance on the battlefields of antiquity.