Kitchen Speak

What Is That and How Do I Pronounce It?

Test Your Cooking IQ

Basic Kitchen Vocabulary

Memorize This!

Is “Al Dente” Pasta a Good Thing?

Cheat Sheet

La Cuisine Française: Commonly Misunderstood (and Mispronounced) French Food Terms

The first step in the successful completion of a recipe is understanding what it is telling you to do. Cooking has its own special vocabulary; an entire lexicon has evolved to translate what happens in the kitchen to the printed page. Some recipes are precise blueprints, specifying particular sizes, shapes, quantities, and times. Other recipes are rough sketches that leave the cook to fill in the blanks. If you don’t talk the talk, you’re going to be in trouble. Unfamiliar terms can cause a real problem if you simmer when you’re supposed to boil, or chop when you should dice. Specialized vocabulary can also be an issue at the grocery store, where packaging comes covered in jargon and buzzwords. And what about the indecipherable language of restaurant menus? If you aren’t sure what a word means, you should always check before proceeding with a recipe or purchasing a product. Start with the helpful notes in this chapter and you’ll be fluent in foodie before you know it!

Match each cooking term to the correct definition.

Cooking Terms

| Boil Deglaze Chop |

Sweat Fold Poach Simmer |

Toast Sear Dice |

1 To heat a liquid until small bubbles gently break the surface at a variable and infrequent rate.

2 To cook food over gentle heat in a small amount of fat in a covered pot.

3 To cook food in hot water or other liquid that is held below the simmering point.

4 To heat a liquid until large bubbles break the surface at a rapid and constant rate.

5 To cook food over high heat, without moving it in the pan, usually with the goal of creating a deeply browned crust.

6 To cut food into uniform cubes (exact size depends on the recipe).

7 To mix delicate batters and incorporate fragile ingredients using a gentle under-and-over motion that minimizes deflation.

8 To use liquid (usually wine or broth) to loosen the brown fond that develops and sticks to a pan during the sautéing or searing process.

9 To cook or brown food by dry heat, and without adding fat, using an oven or a skillet on the stovetop.

10 To cut food into small pieces (⅛ inch to ¾ inch, depending on the recipe).

Sometimes there isn’t a convenient or safe place to put a hot pan. If a recipe says “off heat” or “remove from heat,” do I really need to take the pan off the burner, or can I just turn the heat off?

Physically moving the pan off the heat is pretty important, especially if you have an electric stove.

We went into the test kitchen and brought a saucepan of water to a boil several times, recording its temperature change over a three-minute period as it sat on top of the same burner (turned off) as opposed to sitting on a trivet on the countertop. Left on the hot grate of the gas burner, the water in the saucepan remained 10 degrees higher than when the pan was moved to the countertop. When the pan was left on an electric burner, the temperature difference was even greater: The water remained 30 degrees hotter.

While these temperature differences probably won’t matter for large pots of stew or pasta sauce, we wondered if they could adversely affect more delicate, heat-sensitive recipes. To find out, we made three batches each of a simple pan sauce and a vanilla custard pie filling, one batch taken completely off the heat when directed by the recipe, one left on the hot grate of a gas burner, and one left on the hot coil of an electric burner. In the 30 seconds that the pans sat on the gas burner while additional ingredients were whisked in, no adverse reaction occurred in either the sauce or the custard. However, when left on the electric burner (which retains heat for a longer period of time), the sauce became darker and clumpier, with a slightly oily rather than rich and glossy texture, and the custard became thick and pasty.

So the next time a recipe calls for adding an ingredient “off heat,” don’t just turn off the burner (especially if it’s an electric burner). Take the extra two seconds to move the pan completely off the heat, onto either a trivet or a cool, unused burner.

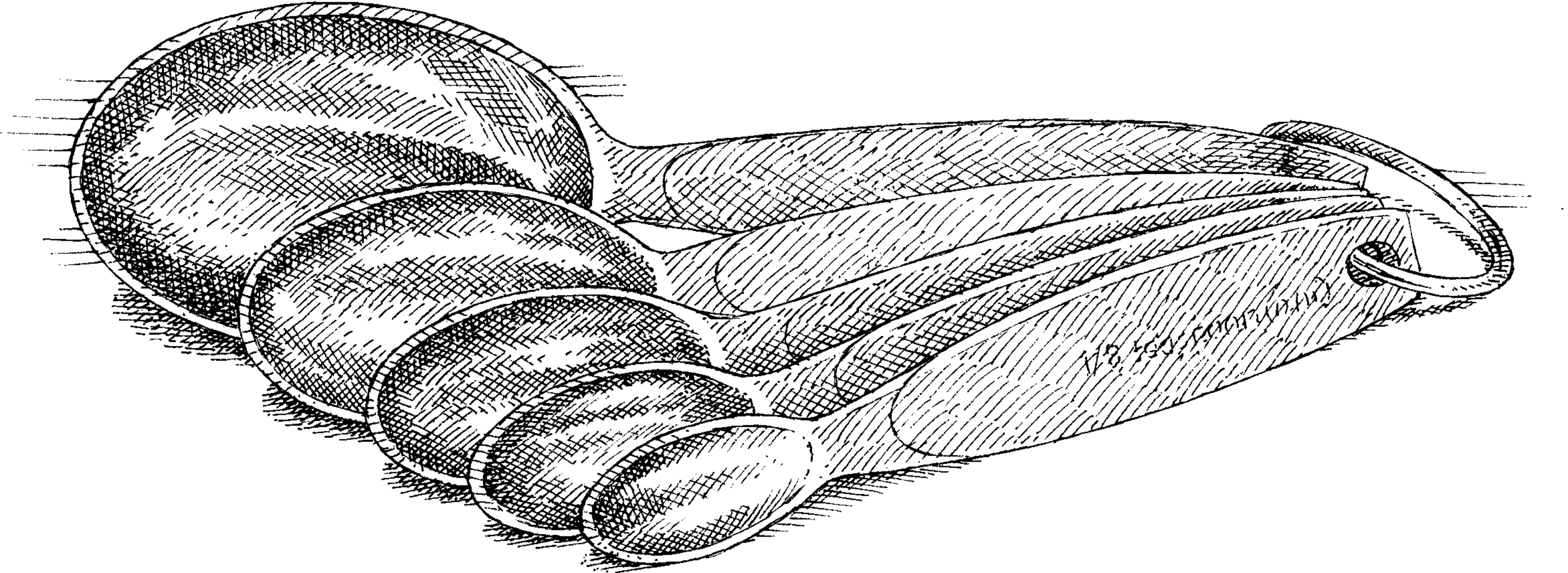

How do I measure a “pinch” of an ingredient? What about a “dash”? And a “smidgen” isn’t a real thing, right?

Traditionally these measurements were pretty vague, but these days there are slightly clearer rules.

We’re pretty particular about measuring—you should always select the appropriate tools for the type of ingredient you’re measuring and use them properly (see here). We also have rules for exactly how to treat tricky ingredients like delicate greens or fluffy grated cheese (see here). And of course, whenever possible, we prefer to use weight instead of volume for maximum accuracy. However, sometimes you need just a tiny amount of an ingredient—a pinch of this, a dash of that, a smidgen of the other thing. While these terms were used pretty vaguely in the past, recently manufacturers have begun offering measuring spoons labeled with them. The general consensus is that a dash is ⅛ teaspoon, a pinch is ½ dash or ¹/16 teaspoon, and a smidgen is ½ pinch or ¹/32 teaspoon. If you’re committed to complete precision, you can use these measurements. However, since they are difficult to achieve without a set of measuring tools exactly calibrated to these rules, and since these are very small amounts in any case, you’re probably OK estimating. If we use the word “dash” in a recipe, we usually mean a small splash of a liquid ingredient added to taste, and if we use the word “pinch,” we mean the amount of a dry ingredient you can literally pinch between your thumb and forefinger. We don’t use the word “smidgen” in recipes.

Many of my favorite recipes include a step where the ingredients are either “caramelized” or “browned.” But aren’t caramelizing and browning the same thing?

In a word, no: These are two different processes that happen in different circumstances.

Lots of people—even professional chefs—use “caramelize” and “brown” interchangeably, but if you look at the science behind these flavor-boosting techniques, they’re actually quite different (though both, of course, lead to a literal “browning” of the food).

Caramelization describes the chemical reactions that take place when any sugar is heated to the point that its molecules begin to break apart and generate hundreds of new flavor, color, and aroma compounds. Consider crème brûlée: After being exposed to high heat, the sugar atop the custard turns golden brown, with rich, complex caramelized flavors. (A similar process takes place when you cook onions, carrots, apples, or any other high-sugar fruit or vegetable; the food’s sugars caramelize once most of the moisture has evaporated.)

As for browning, here the process involves the interaction of not just sugar molecules and heat but also proteins and their breakdown products, amino acids. Foods that benefit from browning include grilled and roasted meats and bread. Like caramelizing, browning creates a tremendous amount of flavors and colors, but they’re not the same as those created by caramelization, because protein is involved. Another name for browning is the Maillard reaction, after the French chemist who first described these reactions in the 1900s.

I am confused about the meaning of the term “proof” in bread baking. Does it have to do with the yeast or the dough?

No wonder you’re confused: The term “proof” has two meanings—one having to do with yeast and the other with dough.

Proofing yeast is a quick way for bakers to determine whether the yeast spores in active dry yeast or cake yeast are active. If these types of yeast have an extended stint in the refrigerator or if their age is unknown, it is a good idea to test them before using them in a recipe. To do so, fill a glass bowl or measuring cup with the amount of lukewarm water (105 to 115 degrees) called for in the recipe, add a pinch of sugar, and whisk until dissolved. Now sprinkle the yeast granules over the surface of the sugar water and whisk again. If active, the yeast will feed on the sugar and begin to foam and swell in five to 10 minutes. At this point, it is safe to proceed with the recipe. If there is no activity, the yeast will not do its work in the recipe and should not be used. Instant yeast, which is what we use in our test kitchen, does not require proofing. Each package is marked with an expiration date and, if used within the specified time, should be active.

The other use of the term “proof” denotes a stage in the rising of dough. After its first rise, dough is deflated, or punched down, and shaped into its final form. The shaped dough is then set out for its final rise and fermentation before baking; this is the step that is referred to as proofing. Fermentation allows flavors to develop for better-tasting bread. Most bread recipes recommend proofing dough at room temperature under plastic wrap or a clean, slightly damp, lightweight towel to prevent dehydration. Some doughs proof quickly; others need to proof overnight. A reliable way to test the dough’s progress is to touch it lightly with a moistened finger. At first, the dough will feel firm and will bounce back to the touch. At the halfway mark, it will feel spongy on the surface but firm underneath. It is ready for the oven when it feels altogether spongy and when the indentation left in the dough fills in slowly. If the indentation doesn’t fill in at all, the dough has overproofed and is in danger of collapsing in the oven.

I’ve occasionally seen the word “short” used in articles on baking, as in adding “shortness” to pastry. Can you tell me what this means?

For bakers, “shortness” is a term used to describe the level of tenderness in a dough.

Bakers must be nothing if not precise, so it should come as no surprise that they have a term reserved for a particularly important aspect of pastry: its tenderness. When bakers talk about shortening a pastry, they’re essentially talking about increasing its tenderness, making it more crumbly. A shortbread cookie is a perfect example of shortness; it is so tender, so crumbly, so short that it nearly melts in your mouth.

To find out how the term “short” entered the baker’s vocabulary, we turned to Ben Fortson, senior lexicographer at the Boston-based American Heritage Dictionary. He told us that one of the original meanings of short was “friable,” as in easily crumbled or crushed into powder. The first documented use of “short” as applied to baking was in a cookbook in England around 1430, Fortson said, while the term “shortening” as we know it in baking first appeared in America in 1796. Yet another, certainly less pleasant (though no less useful) application of “short” in this sense of crumbly or friable showed up in England in 1618, when farmers were in the habit of adding straw to manure to make it break up more easily when used as a fertilizer. They called their creation “short manure” or “short muck.”

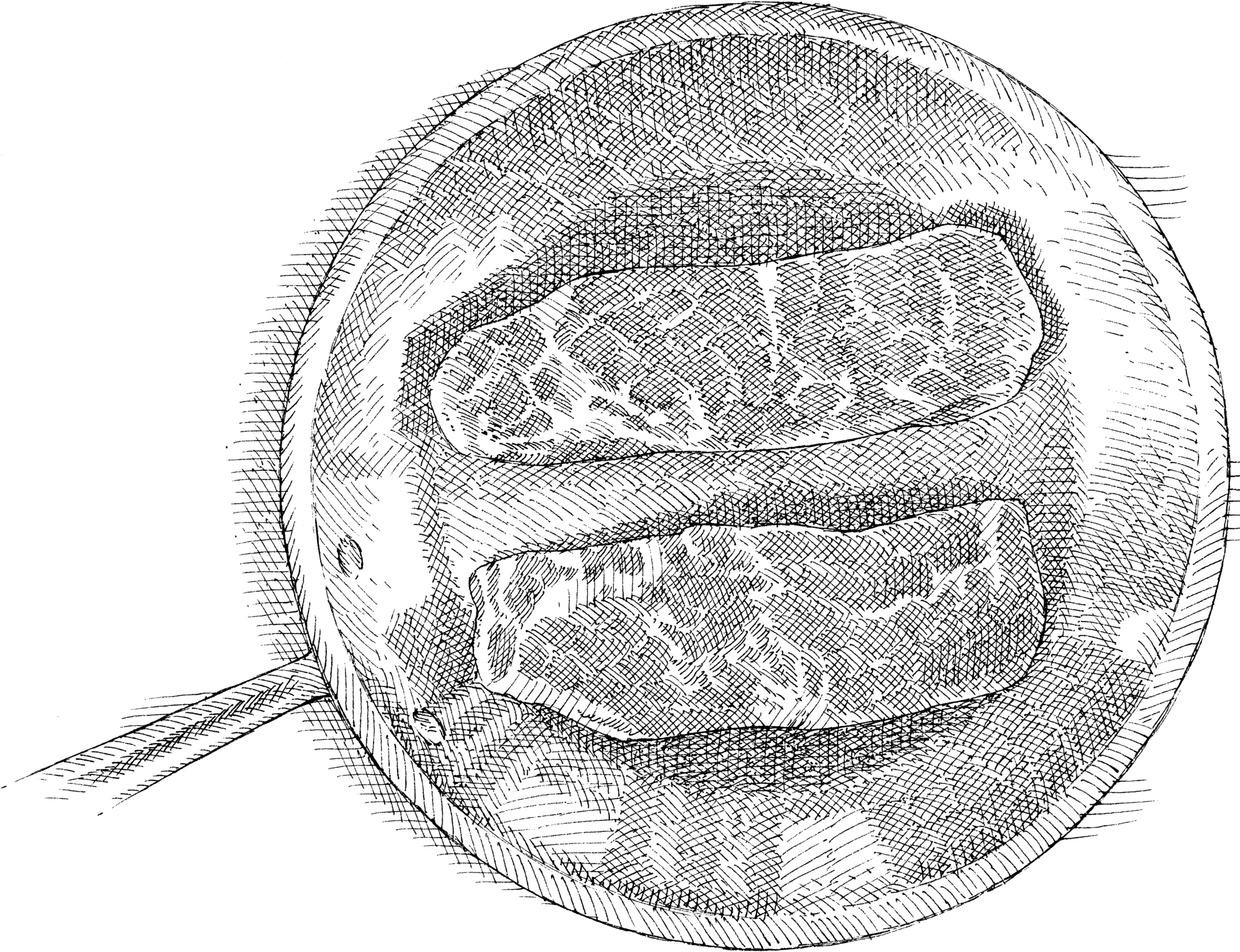

I’ve seen articles on baking that mention the desirability of a “closed crumb” versus an “open crumb.” What are bakers talking about when they refer to “crumb”?

These are descriptions of the texture of the baked good; different types of crumb are ideal for different types of baked goods.

Bakers use the terms “closed” (or tight) and “open” (or loose) to describe the texture of a baked good, often in reference to its aeration, or the relative size and concentration of the air pockets. A comparison to knitting may be helpful: A very tightly knit sweater with small stitches that lets little air through (and so keeps you warm) would be comparable to a piece of pound cake or brioche. A shawl with a very open pattern would be comparable to the loose crumb that’s typical of an English muffin or a piece of sourdough bread. Crumb is affected by nearly everything that goes into a cake or bread: the type of flour, the amount of yeast or chemical leavener, and the amount of liquid. In general, tenderness is characteristic of a fine, tight crumb, while chewiness goes along with the open crumb of artisan breads such as sourdough.

Is there a difference between “frosting” and “icing”?

There’s no hard-and-fast rule, but generally frostings are thick and fluffy, while icings are thin and smooth.

Some food encyclopedias define frosting as the American word for icing, and a handful of culinary dictionaries state that frosting and icing are one and the same, but most other sources differentiate the two. They define frostings as relatively thick, sometimes fluffy confections that are spread over a cake or used to fill it. Icings are considered to have a thinner consistency and are usually poured or drizzled over baked goods as opposed to spread. They form a smooth, shiny coating. Also commonly noted about icings is that they are typically white.

What does it mean to “coddle” an egg? How is it different from poaching?

Coddled eggs are cooked in the shell; poached eggs are not.

Both coddling and poaching refer to cooking something gently in water heated to just below the boiling point. With eggs, the difference comes down to the shell: Poached eggs are cooked without the shell, directly in the simmering water (often with vinegar added to help the whites set). Coddling, on the other hand, involves cooking the eggs still protected by their shell (or by individual covered containers called coddling cups). Lightly coddled eggs (cooked for about 45 seconds, just to thicken the yolks slightly) are commonly used in Caesar salad dressing to provide a more viscous texture. When cooked a few minutes more, to a consistency resembling soft-boiled eggs (the whites are slightly more set), they can be eaten as is.

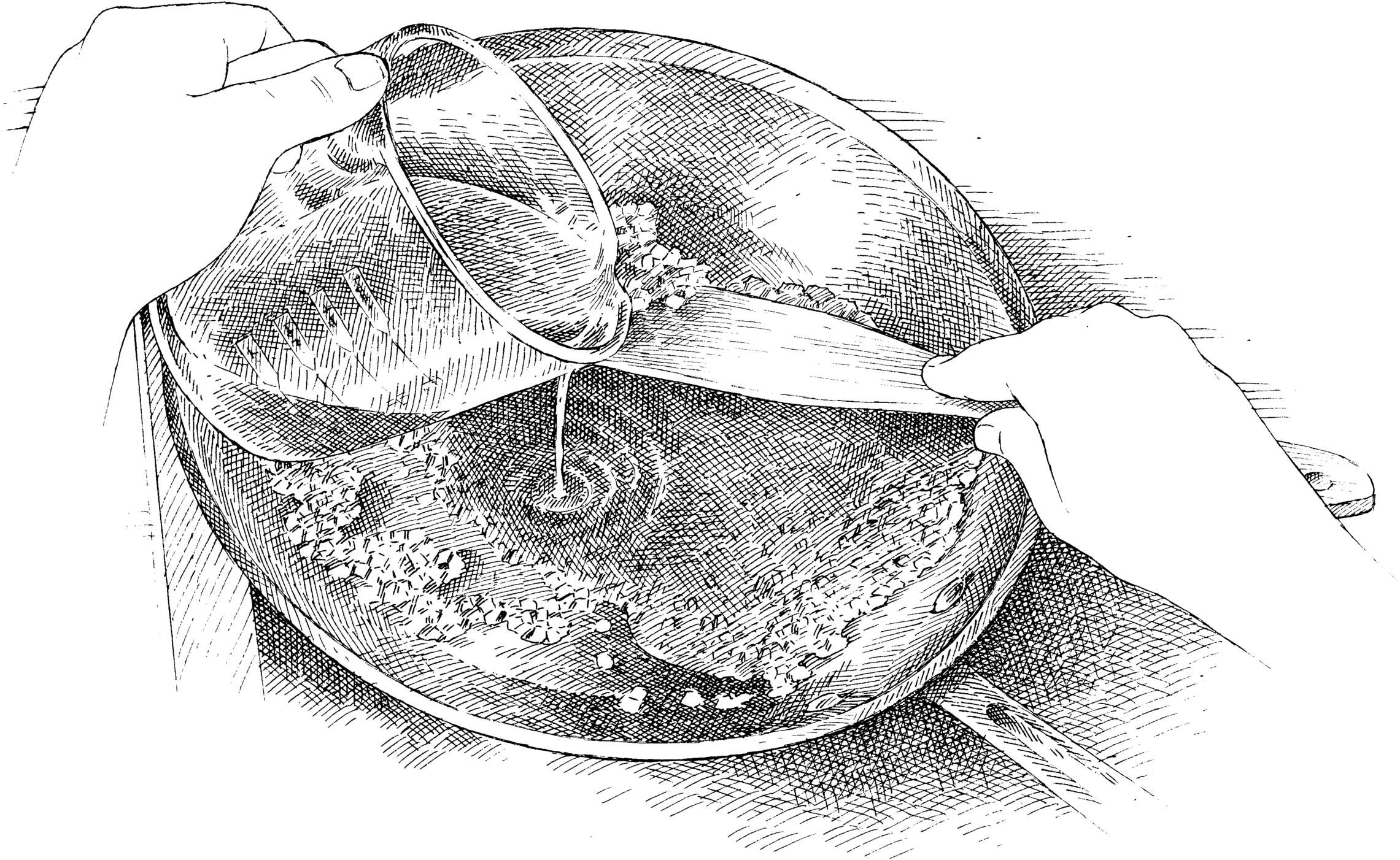

What is a “bouquet garni,” and what does it do for a dish?

A bouquet garni is a bundle of herbs and spices used to flavor a dish; it is removed before serving.

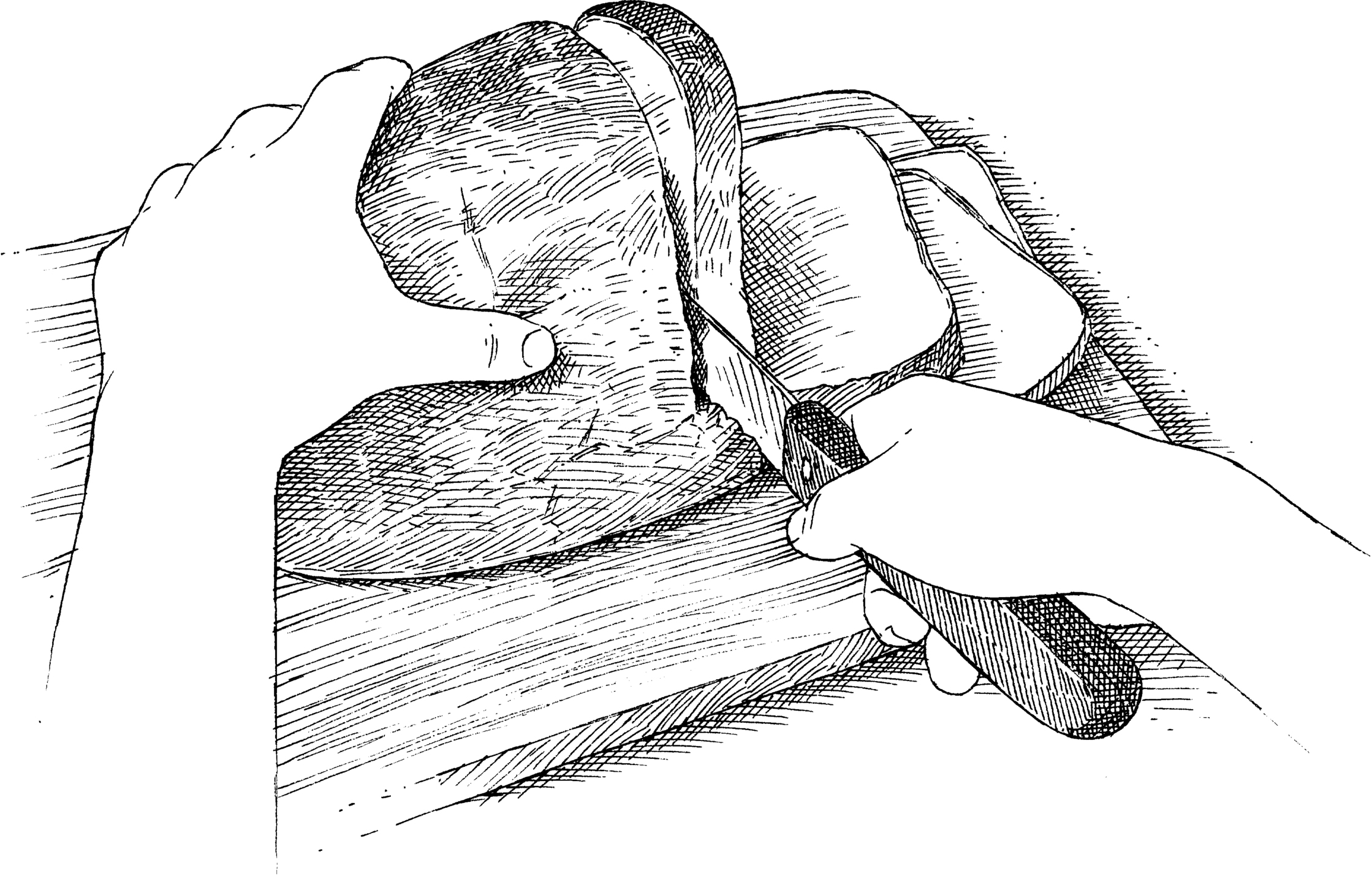

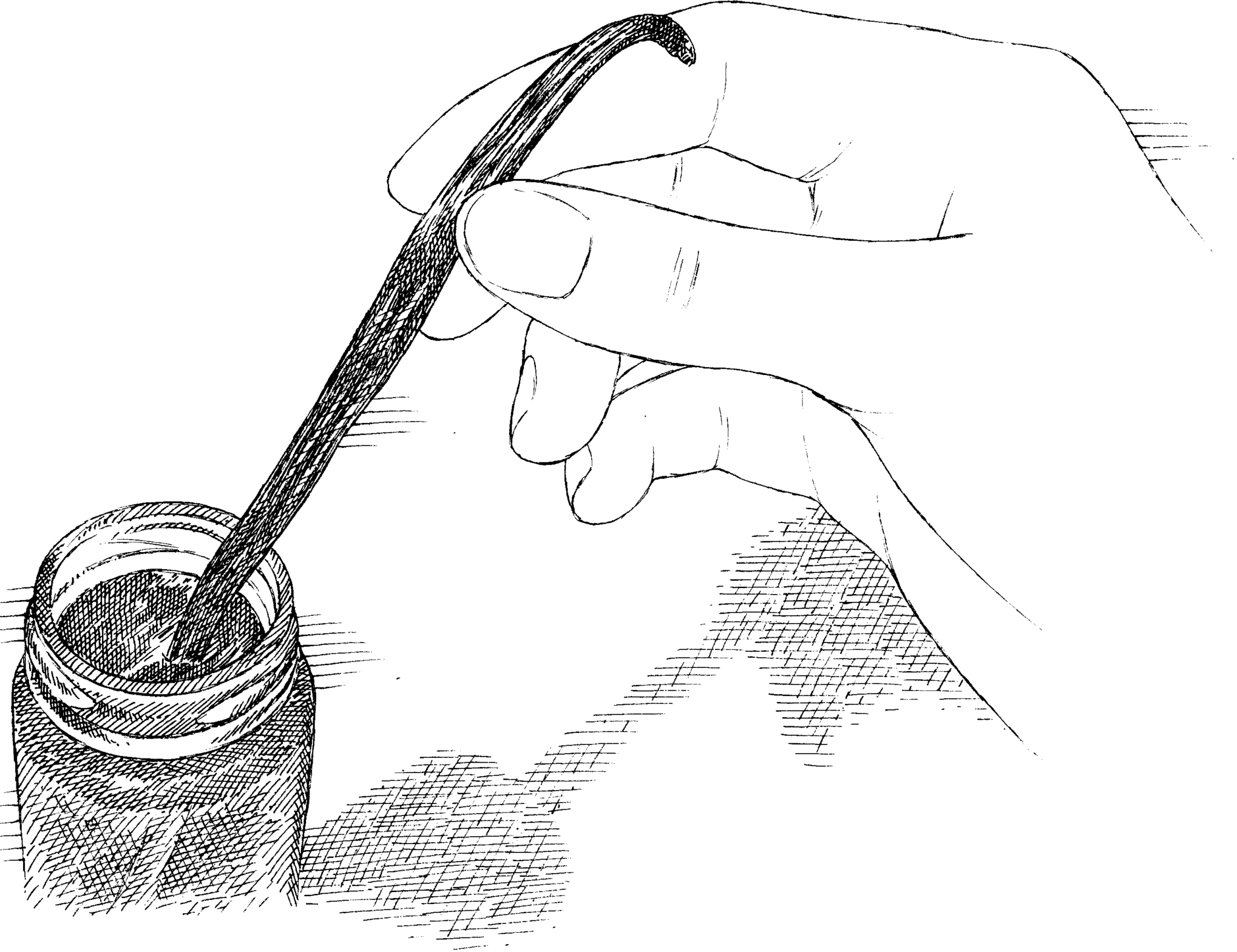

A bouquet garni is a classic combination of fresh herbs used to flavor stocks, soups, and stews. There is no one universal recipe for bouquets garnis, although most variations begin with sprigs of fresh parsley and thyme, plus a dried bay leaf. Possible additions include rosemary, celery, leek, tarragon, savory, fennel, and whole spices, including black peppercorns. All the ingredients are wrapped together, either simply in a bundle tied with kitchen twine or in cheesecloth that’s then tied up with twine. One end of the twine is often left long enough to wrap around the handle of the pot; when cooking is finished, the herb bundle is then easily retrieved and discarded.

What are “herbes de Provence”?

This herb mix includes a variety of herbs native to the Provence region of France.

Herbes de Provence, the aromatic blend from the south of France, traditionally combines dried lavender flowers with dried rosemary, sage, thyme, marjoram, and fennel, and sometimes chervil, basil, tarragon, and/or savory. It’s a natural partner for poultry and pork (used as a rub or in an herb butter) or in other dishes characteristic of the Provençal region, such as lentil salads or ratatouille. You can find it in the spice aisle of most supermarkets or simply make your own simplified version at home. We like a combination of equal parts dried thyme, dried marjoram, dried rosemary, and toasted fennel seeds. Store homemade herbes de Provence in an airtight container at room temperature for up to 1 year.

What is “kombu”? I’ve seen it listed as an ingredient in Japanese dishes, but I’m not sure what it is.

Kombu is a form of dried seaweed that’s used to enhance savory, umami flavors.

Kombu is a dried kelp, rich in flavor-enhancing glutamic acid, that’s used extensively in Japanese cooking. One of its most popular applications is in dashi, Japan’s multipurpose base for soups, stews, and sauces. Japanese cooks often add the seaweed to cold water, which is then brought to a simmer, at which point the kombu is removed (since temperatures above a simmer can pull out off-flavors). We’ve found that kombu can also be used to deepen flavors in nontraditional applications, as when small pieces of it are added to the pot with a vegetable soup’s liquid ingredients or with the tomatoes in a pasta sauce. For every quart of liquid (or liquid-like ingredients), add a 2 by 2-inch piece of kombu (which can be found in Asian markets and many ordinary grocery stores), and be sure to remove it just as the liquid begins to simmer.

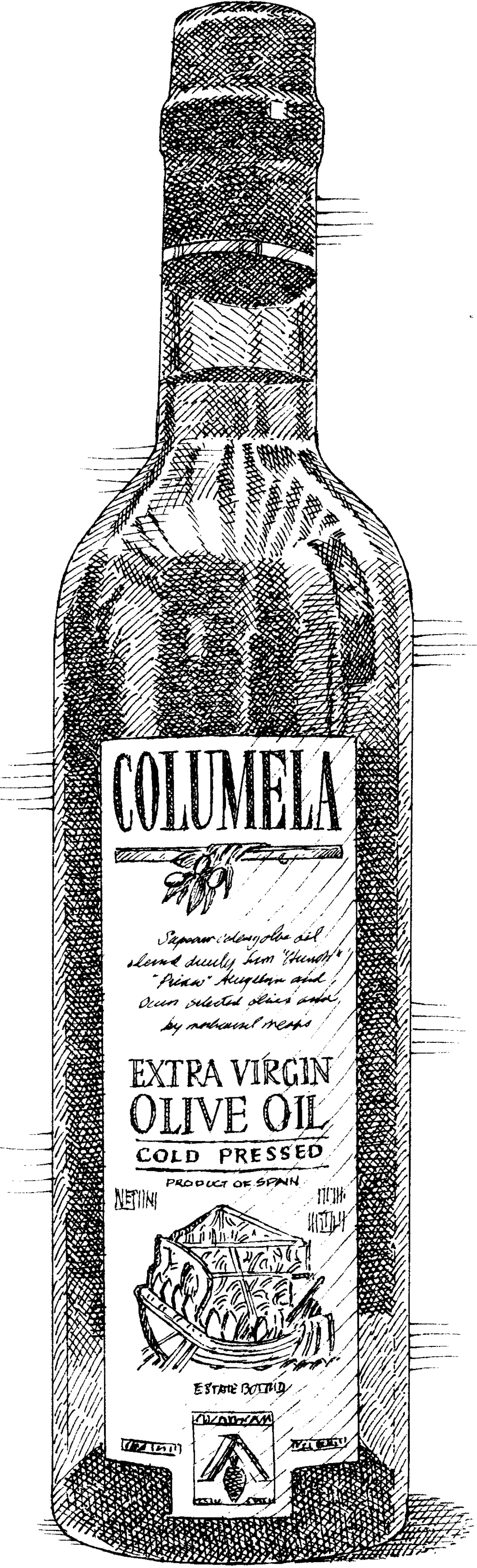

Why is some olive oil called “extra-virgin”? That seems like an odd term to use for oil.

The term itself might be a little odd, but the meaning is pretty important if you like good olive oil.

Olive oil, which is simply juice pressed from olives, tastes great when it’s fresh. Only oil from the very first pressing of olives can be called extra-virgin olive oil. Extra-virgin olive oil is lively, bright, and full-bodied at its best, with flavors that range from peppery to buttery depending on the variety of olives used and how ripe they were when harvested. But like any other fresh fruit, olives are highly perishable, and their pristine, complex flavor degrades quickly, which makes producing—and handling—a top-notch oil time-sensitive, labor-intensive, and expensive.

For all these reasons, olive oil must meet numerous standards in order to achieve official extra-virgin status. These are established by the International Olive Council (IOC), the industry’s worldwide governing body. Extra-virgin oil must meet certain chemical standards, be free of off-notes, and contain some positive fruity flavors. Unfortunately, these standards were largely unenforced in the United States until recently, so lower-quality oils were being passed off as extra-virgin. In the past few years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has adopted similar chemical and sensory standards to those used by the IOC in order to better regulate the olive oil most Americans buy at the supermarket. Add extra-virgin olive oil to dishes after cooking, or save it for vinaigrettes; don’t use the good stuff for pan-frying, since its delicate flavors break down when heated.

What can labels like “dark” and “light” on ground coffee and coffee beans tell me about how they taste?

Not much, but the roast color can tell you whether the coffee is better black or with milk.

The degree to which coffee beans are roasted has as much of an impact on their final profile as their intrinsic flavors. While coffee roasters use a variety of names to categorize the darkness of their roasts (Italian, French, Viennese), there are no industry standards for this nomenclature. We’ve found it’s more useful to categorize roasts by color. At one end of the spectrum are light roasts, characterized by pale brown color and bright, fruity, more acidic flavors. As roasting continues, color deepens, acids are broken down, and sweeter flavors begin to surface.

Choosing your roast is a matter of preference, but how you take your coffee is also a consideration. We prefer drinking lighter roasts unadulterated; when milk is added, our preference switches to darker roasts. The proteins in milk and cream bind some of the bitter-tasting phenolic compounds in the more deeply roasted beans, reducing both bitterness and intensity of coffee flavor.

| Roast | Color/ Texture | Flavor |

| Light | Pale brown with dry surface | Light body and bright, fruity, acidic flavor |

| Medium | Medium brown with dry surface | Less acidity and the beginnings of richer, sweeter notes |

| Medium-Dark | Dark mahogany with slight oily sheen | Intense, caramelized flavors with subtle bittersweet aftertaste |

| Dark | Shiny black with oily surface | Pronounced bitterness with few nuances |

I’ve heard some red wines described as “tannic.” Can white wines be tannic, too?

While white wines may contain tannins, their levels are too low to produce the bitterness and astringency that we would characterize as tannic.

Wines that are characterized as tannic are high in tannins, which are chemical compounds known as polyphenols that occur naturally in wood, plant leaves, and the skins, stems, and seeds of fruits like grapes, plums, pomegranates, and cranberries. Tannins have a bitter flavor and astringent quality that has a drying effect on the tongue. One of the challenges of wine making is striking a favorable balance between tannins and sweetness, and wines are manipulated to enhance or suppress either characteristic depending on the varietal. Intense, full-bodied red wines like Malbec or Cabernet Sauvignon are often high in tannins, since the pressed grape juice spends a good deal of time in contact with the grape skins, stems, and seeds before being aged in wood barrels (another source of tannins).

White wines tend to be significantly lower in tannins than red wines since the juice spends so little time exposed to the grape skins. Any tannic characteristics they do exhibit are more likely the effect of oak aging.

What does it mean when a food is “fermented”?

Fermentation is a set of reactions that occur when bacteria and/or yeasts interact with food, changing its flavor, texture, and aroma and helping preserve the food.

Fermentation is a process in which bacteria and/or yeasts consume carbohydrates and proteins naturally present in food, producing alcohols, lactic acid, acetic acid, and/or carbon dioxide as byproducts. Water and salt are often added to the mix because both create a fermentation-friendly environment. (Salt can also keep bad bacteria at bay.) Fermentation helps preserve food and alters its flavor, texture, and aroma. Fermented foods are easy to digest, and their bacteria are thought to offer health benefits—which helps explain their recent uptick in popularity.

Foods like pickles, vinegar, and yogurt have the tang that we often associate with fermentation. And of course beer and wine are fermented. But everyday foods like chocolate, coffee, olives, bread, vanilla, hot sauce, and cheese also get deep flavor from fermentation.

What do “pasteurized” and “ultrapasteurized” mean when it comes to dairy? Is there an advantage to using ultrapasteurized products?

Ultrapasteurization is a version of pasteurization specially designed for dairy that might sit on the shelf longer, such as heavy cream, to help it last longer.

Pasteurization, developed in the 1860s by French scientist Louis Pasteur, is the process of applying heat to a food product to destroy pathogenic (disease-producing) microorganisms and to disable spoilage-causing enzymes. Because cow’s milk is highly perishable and an excellent breeding ground for bacteria, yeast, and molds, it and other dairy products are among the most highly regulated and monitored foods in the United States. Heating milk kills 100 percent of existing pathogenic bacteria, yeast, and molds and 95 to 99 percent of other, nonpathogenic bacteria. Rapid cooling and subsequent refrigeration retard the growth of the survivors, which would eventually cause spoilage.

Ultrapasteurization was developed to solve the problem of slow-selling items such as eggnog, lactose-reduced products, and cream. Ultrapasteurized products are heated to 280 degrees or higher for at least two seconds and packaged in an aseptic atmosphere in sterilized containers. This process destroys not only all pathogenic organisms but also those that cause spoilage. Combined with sterile packaging techniques, ultrapasteurization extends shelf life to as much as 14 to 28 days after opening, if properly refrigerated. However, ultrapasteurization also destroys some of the proteins and enzymes that promote whipping, and the higher heat leaves the cream with a slightly cooked taste that our tasters detected, eliminating the more complex, fresh taste of pasteurized cream.

If you take cream in your coffee, or need to keep cream around for more than a few days, reach for ultrapasteurized (organic, if available). Mixed with coffee’s strong taste, its flavor deficit will go unnoticed, and the cream will last much longer in your refrigerator. But if you plan to use cream on its own, whether whipped or poured over berries, seek out the pasteurized version—you’ll be glad you did.

What make plastics “food grade”?

This term really just means “plastic meant for use with food.”

Food-grade plastic is simply plastic that was manufactured with the intent of being used with food. The ingredients in the plastic must be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to ensure that they do not leach into the food under the intended use. A garbage bag is not intended for storing food, but a zipper-lock bag is. However, note that you can get into trouble if you don’t follow manufacturers’ recommendations. For instance, excessive heat can promote the leaching of chemicals in plastics into food. Make sure to read labels to see whether (and how) plastic containers can be heated.

What is rose water, and how is it used in cooking?

Rose water is an essence of rose petals commonly used in Middle Eastern and Indian cooking.

Rose water is a floral, perfumelike flavoring made by boiling crushed rose petals and condensing the steam in a still. It is used in Middle Eastern and Indian desserts, sometimes in conjunction with orange blossom water. In Middle Eastern cooking, rose water is often used in cakes, puddings, fruit salads, confections, and baklava. It plays a similar role in sweets from northern India, such as gulab jamun, which are deep-fried milk powder balls soaked in a cardamom- and rose-flavored syrup. Rice pudding is another common application.

We purchased three brands of rose water and tasted them in a Middle Eastern rice pudding that calls for 2 tablespoons of the flavoring. Tasters found that the brand containing “natural flavors” had the subtlest flavor, which they liked. The others had stronger profiles that struck our tasters as “fake-tasting” and “overwhelming.” Rose water can be found in the international section of some supermarkets and at Middle Eastern and Indian grocers. Rose water is also sold as a beauty product, so make sure to buy a bottle that is labeled for culinary use if you plan to cook with it. If you’re not used to its flavor, start out by using slightly less than the recipe calls for. A little goes a long way, and you can always add more.

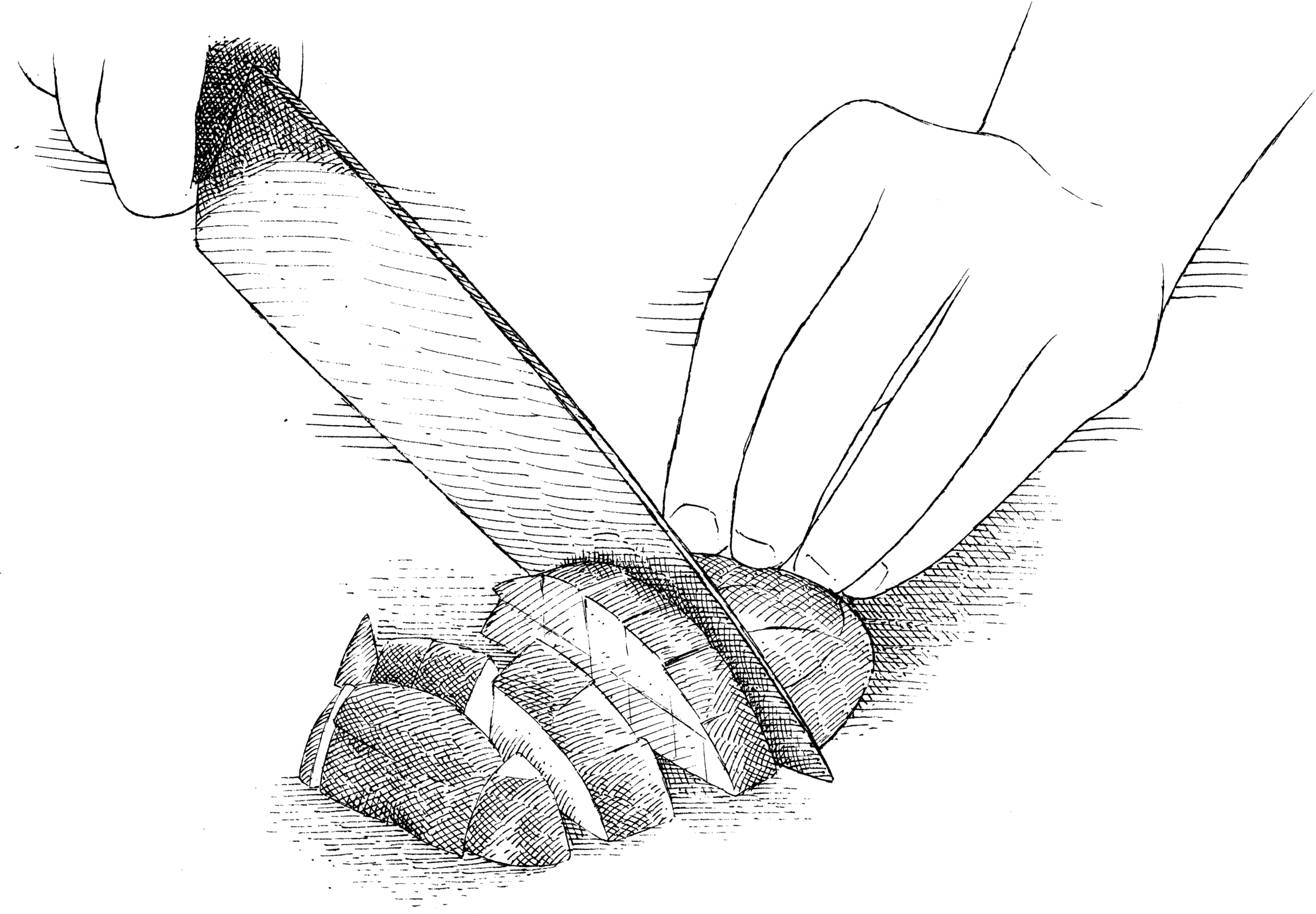

What are ramps? I keep seeing them at farmers’ markets.

Ramps are closely related to onions, leeks, and scallions.

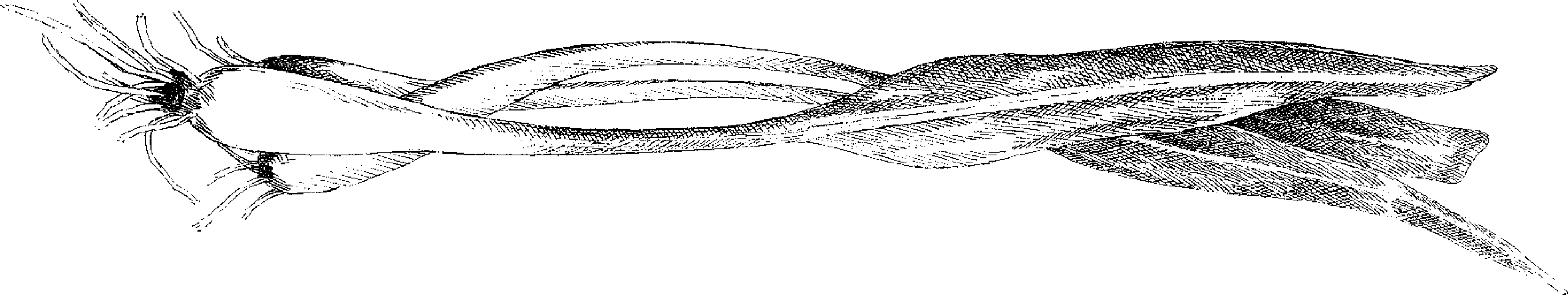

The ramp (also known as wild leek, wild garlic, or ramson) is a member of the onion family that sprouts up in early spring. The bulb looks a little like a scallion, but the leaves are flatter and broader. Both bulb and leaves can be used raw or cooked in applications that call for onions, leeks, or scallions. To prepare ramps, trim off the roots, remove any loose or discolored skin, and rinse well. We sampled ramps sautéed in butter and tossed with pasta, as well as pickled in a simple vinegar mixture. Tasters described the flavor as slightly more pungent than more familiar alliums, with hints of garlic and chive. The raw leaves are slightly grassy, reminiscent of a mild jalapeño.

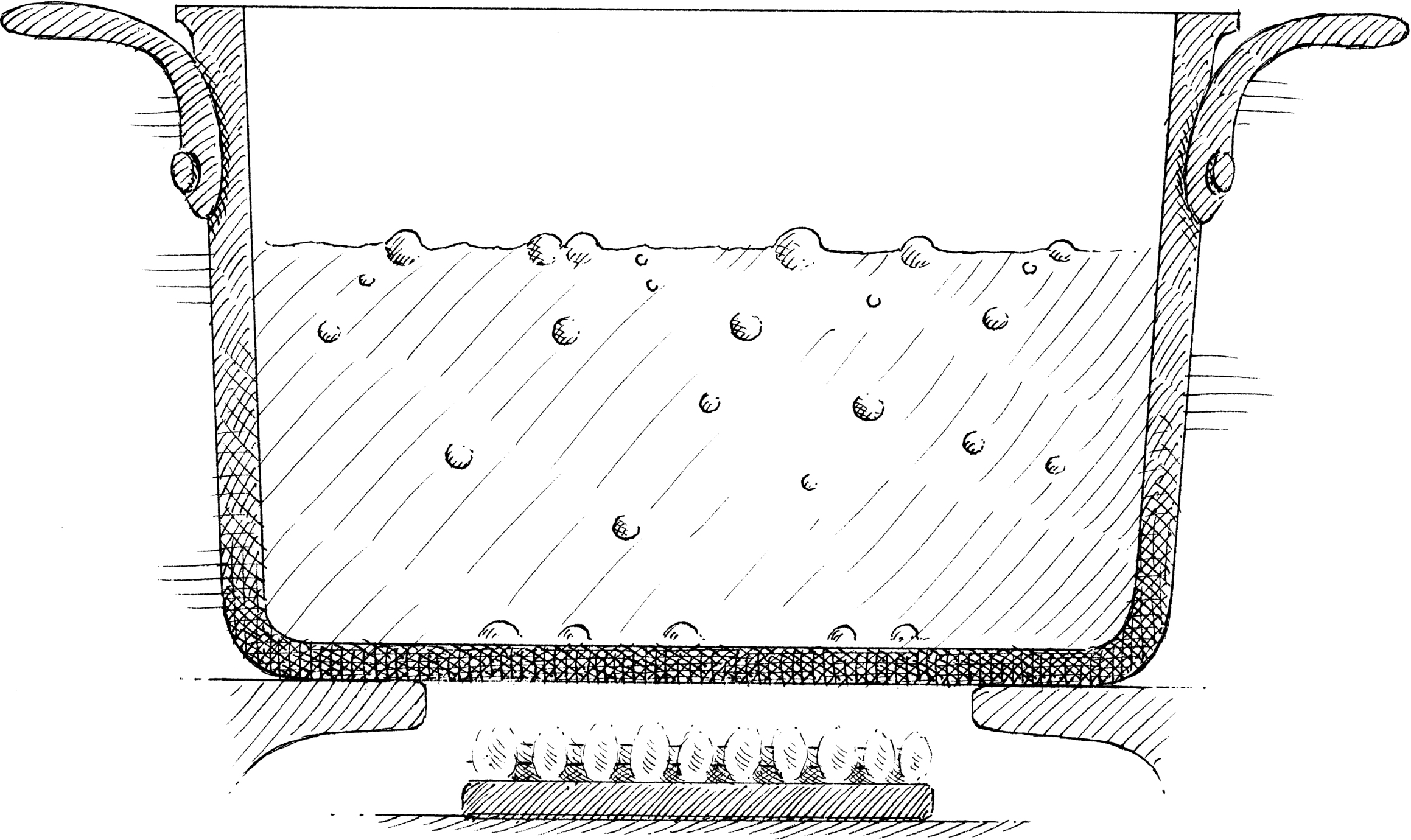

There is one term you need to know for perfect pasta: al dente. This Italian phrase means “to the tooth,” and it’s used as a doneness instruction for pasta, rice, and other grains. It indicates food that is fully cooked but still firm when bitten into. For perfectly al dente pasta, you can’t just use the timing instructions on the side of the box. Several minutes before the pasta should be done, begin taste-testing it—that’s really the only way to know when it’s ready (see here). When the pasta is almost al dente, drain it. The residual heat will finish cooking it. Here are our other tips for getting great pasta every time:

Use Plenty of Water

Use 4 quarts of water for every pound of pasta. You’ll need a large pot, but a generous amount of water will ensure that the pasta cooks evenly and doesn’t clump.

Salt the Water, but Don’t Oil It

Once the water is boiling, add 1 tablespoon of salt. Salt adds flavor—without it, the pasta will taste bland. But forget about adding oil to the pot (see here). Adding oil to the boiling water does not prevent sticking; frequent stirring does.

Save Some Water

Before draining, use a liquid measuring cup to retrieve about ½ cup of the cooking water from the pot. Then go ahead and drain the pasta for just a few moments before you toss it with the sauce. (Don’t let your pasta sit in the colander for too long; it will get very dry.) When you toss your sauce with the pasta, add some (or all) of the reserved pasta water to help spread the sauce.

Sauce in the Pot

Returning the drained pasta to the pot and then saucing it ensures evenly coated, hot pasta. You generally need 3 to 4 cups of sauce per pound of pasta.

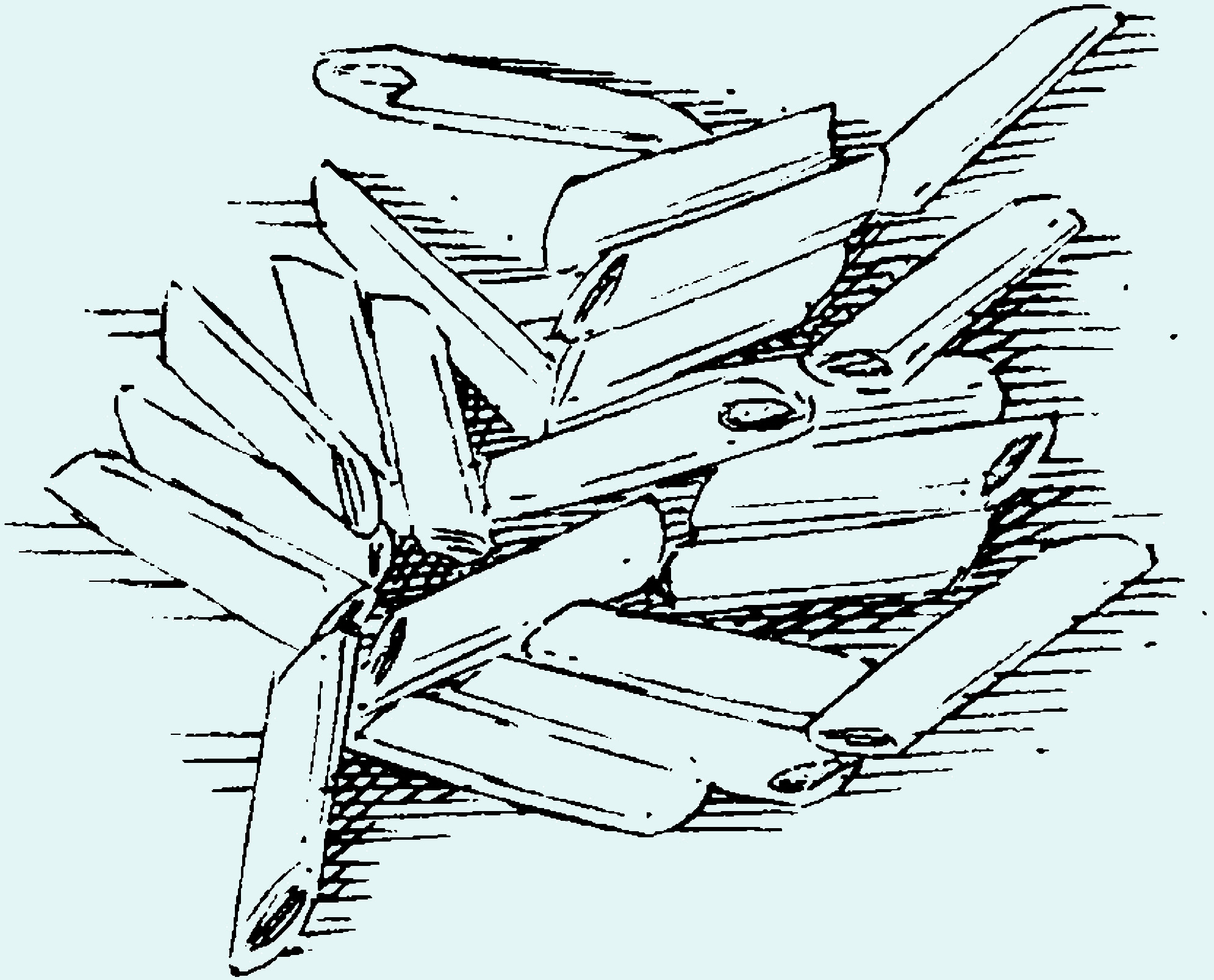

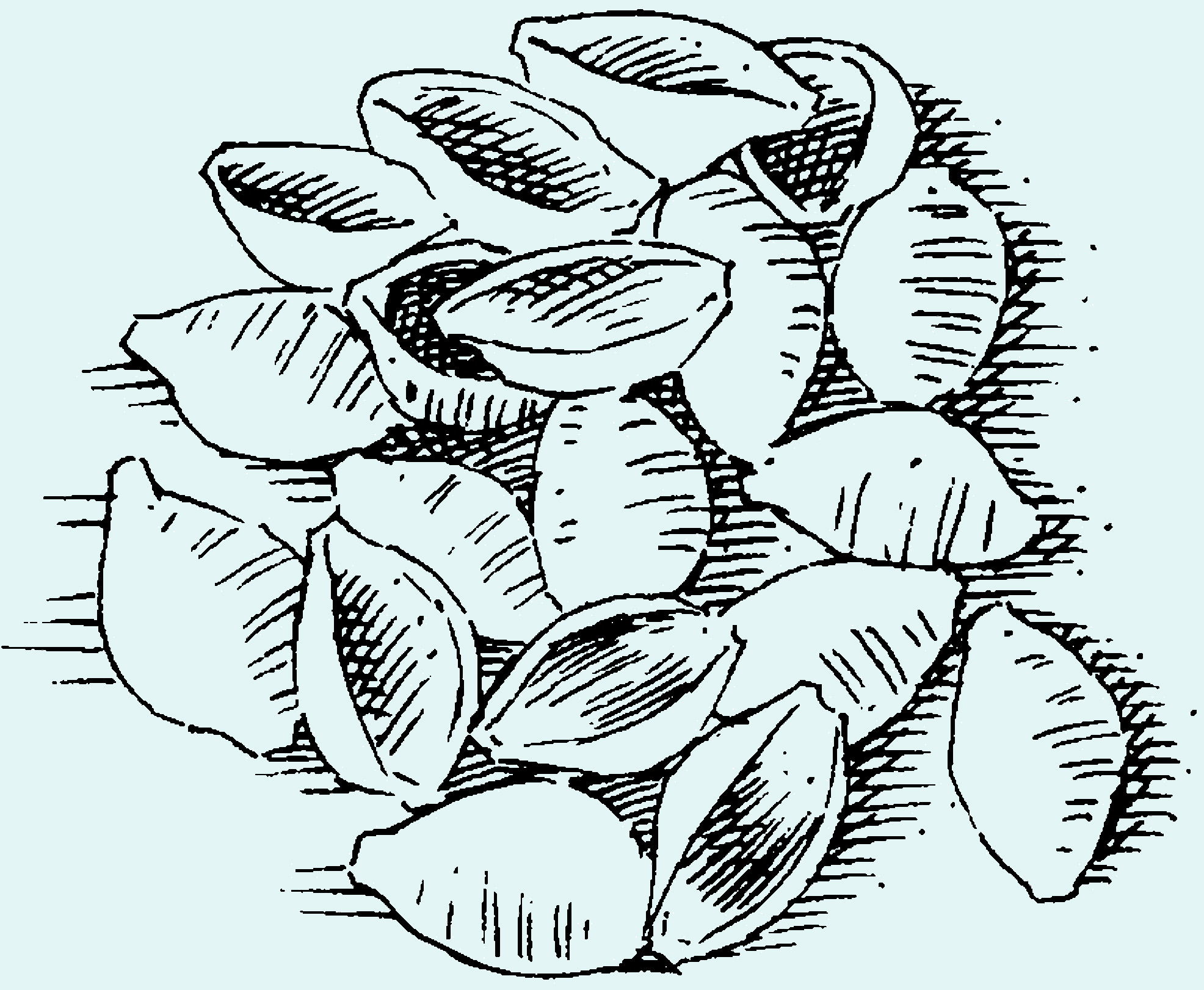

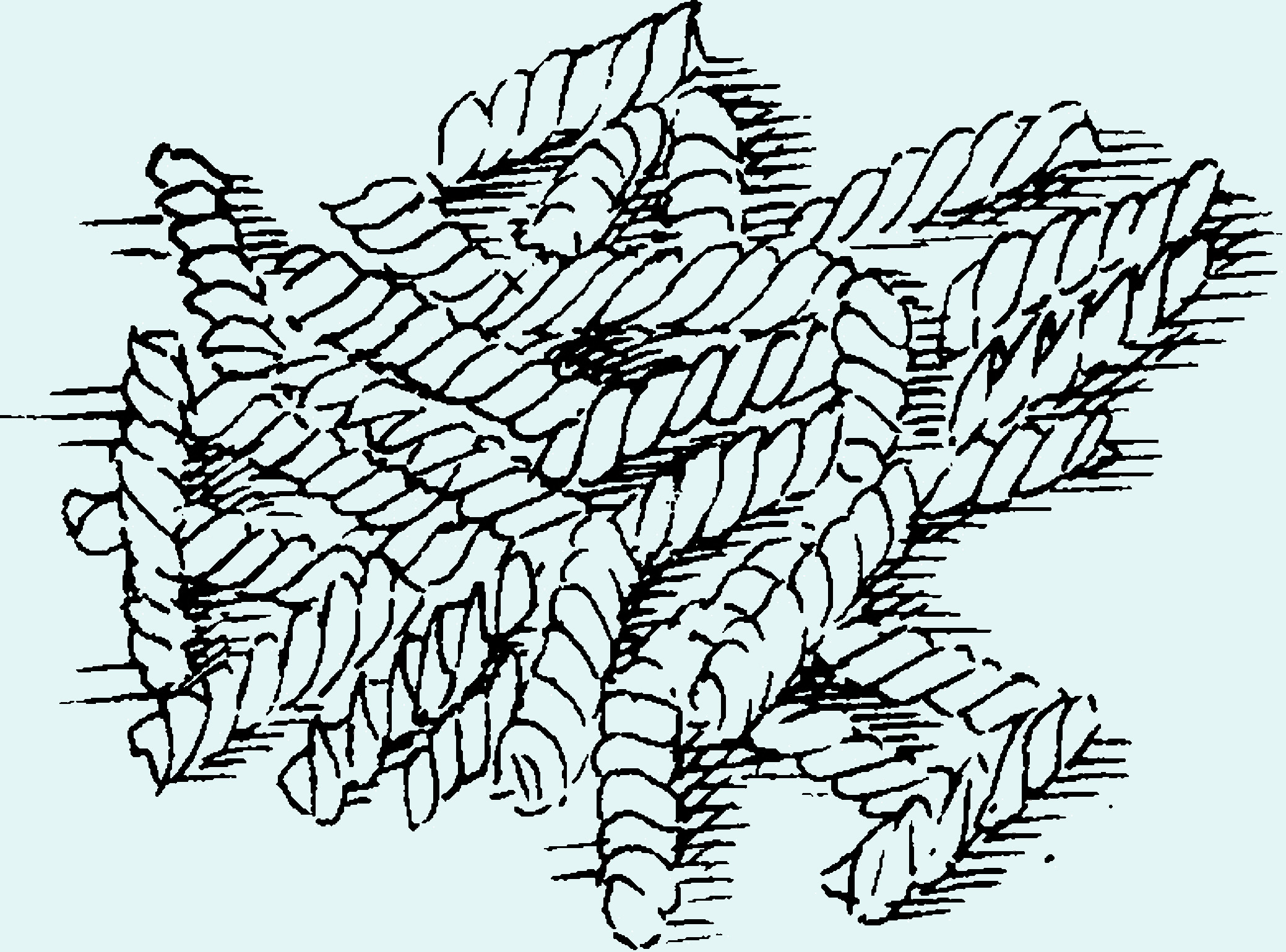

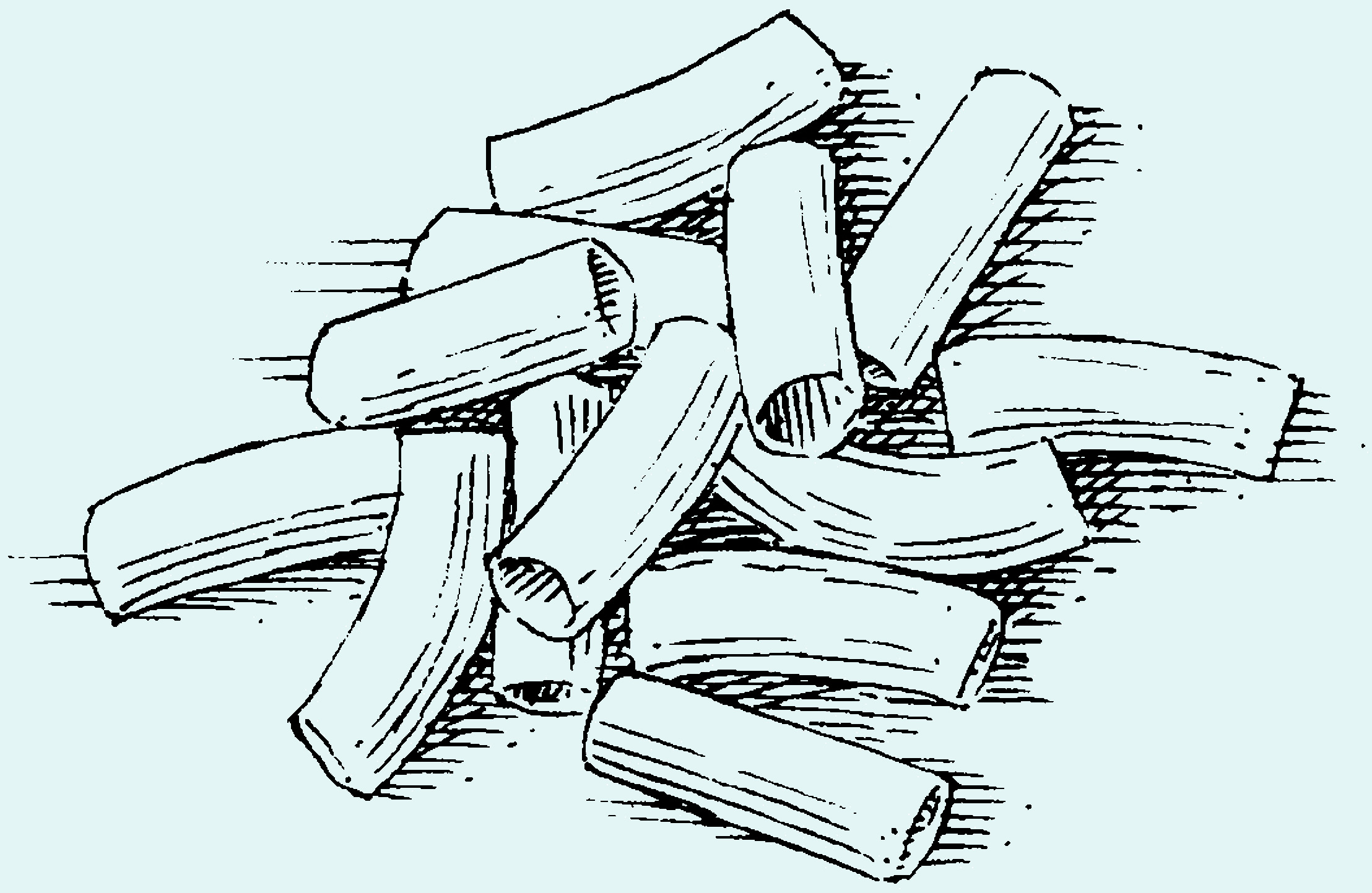

There are dozens of shapes of pasta. Our general rule for matching pasta and sauces is that you should be able to eat some pasta and sauce easily with each bite. This means that the texture of the sauce should work with the pasta shape. In general, long strands are best with smooth sauces or sauces with very small chunks. Wider noodles, such as fettuccine, can more easily support slightly chunkier sauces. Sauces with very large chunks are best with shells, rigatoni, or other large, tube-shaped pastas, while sauces with small to medium chunks make more sense with fusilli or penne.

Pasta in Translation

Here are the most common pasta shapes we use in the test kitchen, along with what their names really mean.

Farfalle butterflies, bow ties

Penne pens, quills

Fusilli little springs

Rigatoni fluted tubes

Fettuccine little ribbons

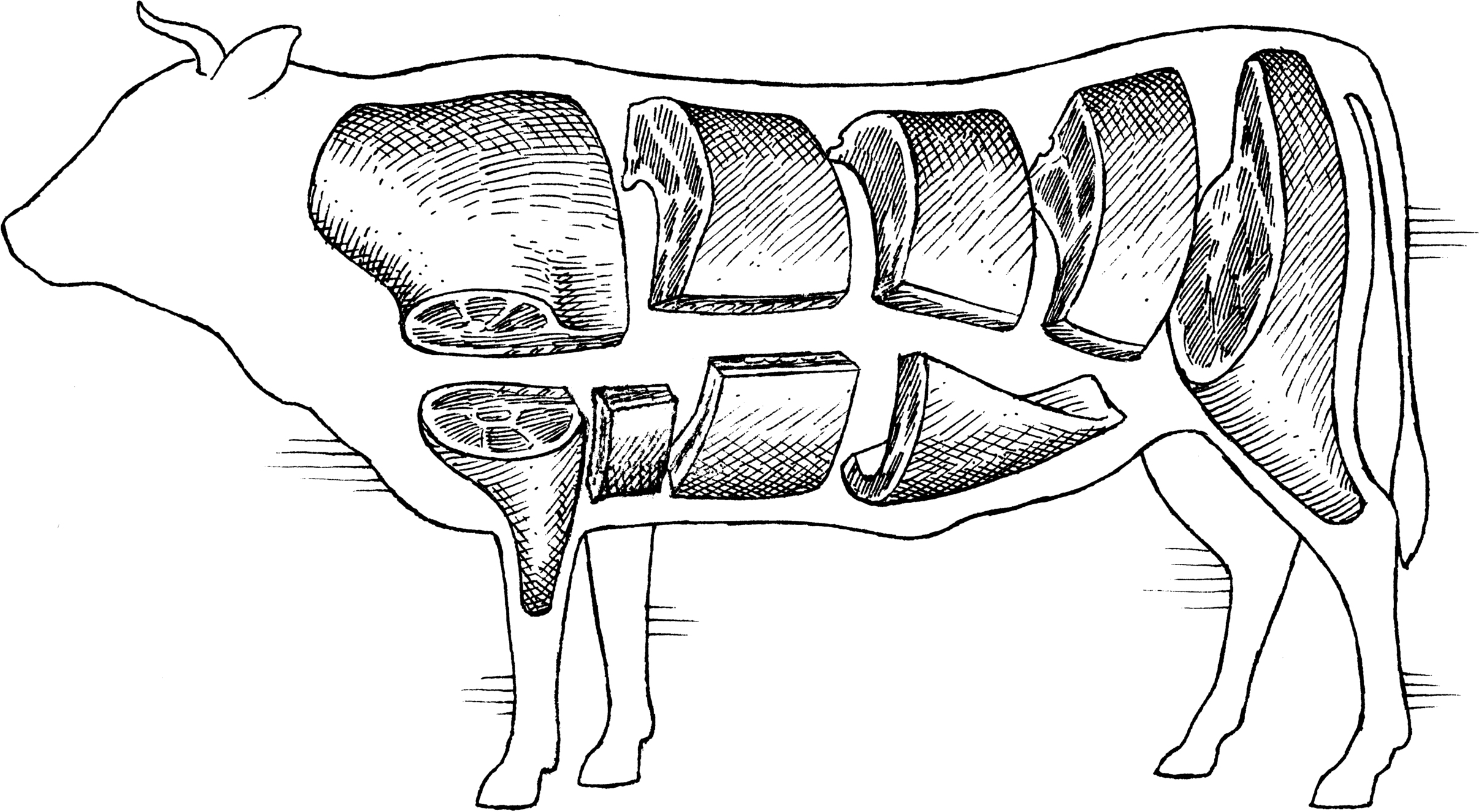

What exactly is “prime” beef, and should I pay extra for it?

To grade meat, inspectors evaluate color, grain, surface texture, and fat content and distribution.

The USDA assigns eight different quality grades to beef, but most of the meat available to consumers is confined to just three: prime, choice, and select. Grading is strictly voluntary on the part of the meat packer. If meat is graded, it should bear a USDA stamp indicating the grade, though the stamp may not be visible to the consumer. To grade meat, inspectors—or, more often today, video image analysis machines—evaluate color, grain, surface texture, and fat content and distribution. Prime meat (often available only at butcher shops) has a deep maroon color, fine-grained muscle tissue, and a smooth surface that is silky to the touch. It also contains fat that is evenly distributed and creamy white instead of yellow, which indicates an older animal that may have tougher meat. Choice beef has less marbling than prime, and select beef is leaner still.

Our blind tasting of all three grades of rib-eye steaks produced predictable results: Prime ranked first for its tender, buttery texture and rich, beefy flavor. Next came choice, with good meaty flavor and a little more chew. The tough and stringy select steak followed, with flavor that was barely acceptable. We’ve found the same to be true for other cuts. Our advice: When you’re willing to splurge, go for prime steak, but a choice steak that exhibits a moderate amount of marbling is a fine, affordable option. Just steer clear of select-grade steak.

I assume “grass-fed” and “grain-fed” refer to what an animal ate, but what do these labels actually mean for the quality and taste of the meat?

Grain-fed beef has long been promoted as richer and fattier, while grass-fed beef has gotten a bad rap as lean and chewy, with an overly gamy taste, but we didn’t find that in our taste tests.

Picking out a steak is no longer as simple as choosing the cut, the grade, and whether the beef has been aged. Now there’s another consideration: the cow’s diet. While most American beef is grain-fed, many supermarkets are starting to carry grass-fed options as well.

To judge the difference between the two types for ourselves, we went to the supermarket and bought 16 grass-fed and 16 grain-fed rib-eye and strip steaks. Because the grass-fed steaks were dry-aged for 21 days, we bought the same in the grain-fed meat. When we seared the steaks to medium-rare and tasted them side by side, the results surprised us: With strip steaks, our tasters could not distinguish between grass-fed and grain-fed meat. Tasters did, however, notice a difference in the fattier rib eyes, but their preferences were split: Some preferred the “mild” flavor of grain-fed beef; others favored the stronger, more complex, “nutty” undertones of grass-fed steaks. None of the tasters noticed problems with texture in either cut.

What accounts for the apparent turnaround in meat that’s often maligned? The answer may lie in new measures introduced in recent years that have made grass-fed beef taste more appealing, including “finishing” the beef on forage like clover that imparts a sweeter profile. Perhaps even more significant is that an increasing number of producers have decided to dry-age. This process concentrates beefy flavor and dramatically increases tenderness.

Our conclusion: For non-dry-aged grass-fed beef, the jury is still out over whether it tastes any better (or worse) than grain-fed. But if your grass-fed beef is dry-aged—and if you’re OK with fattier cuts like rib eye that taste a little gamy—you’ll likely find the meat as buttery and richly flavored as regular grain-fed dry-aged beef.

What does it mean when beef is labeled “blade tenderized”?

Blade-tenderizing is a process used to minimize toughness in chewy cuts of meat.

Blade-tenderized (also known as “mechanically tenderized” or “needled”) meat has been passed through a machine that punctures it with small, sharp blades or needles to break up the connective tissue and muscle fibers with the aim of making a potentially chewy cut more palatable (or an already tender cut more so). But because the blades can potentially transfer illness-causing bacteria from the surface of the meat into the interior, the USDA recommends that all mechanically tenderized meat be labeled as such and accompanied by a reminder to cook the meat to 145 degrees with a resting time of 3 minutes (or 160 degrees with no resting time).

A handful of retailers label their tenderized beef, but if you’re concerned, you can ask your supermarket butcher to confirm whether the meat has been processed in this way. As for the effectiveness of blade tenderizing, we compared tenderized top sirloin steaks and rib-eye steaks with traditional steaks and found that the blade-tenderized steaks were indeed more tender when all the steaks were cooked to a safe 160 degrees. But we prefer our steaks cooked to medium-rare, and since that isn’t advisable with blade-tenderized beef, we’ll stick with traditional meat.

What do the terms “Kobe,” “Wagyu,” and “American Wagyu” beef mean?

Kobe and Wagyu refer to a particular breed of cattle from Japan. American Wagyu is a hybrid breed from the United States.

Wagyu is a breed of cattle originally raised in Kobe, the capital city of Japan’s Hyogo prefecture. Wagyu have been bred for centuries for their rich intramuscular fat, the source of the buttery-tasting, supremely tender meat. Wagyu cattle boast extra fat since they spend an average of one year longer in the feedlot than regular cattle, and end up weighing between 200 and 400 pounds more at slaughter. What’s more, the fat in Wagyu beef is genetically predisposed to be about 70 percent desirable unsaturated fat and about 30 percent saturated fat, while the reverse is true for conventional American cattle.

In order to earn the designation “Kobe beef,” the Wagyu must come from Kobe and meet strict production standards that govern that appellation. The “American Wagyu” or “American-Style Kobe Beef” that appears on some restaurant menus is usually a cross between Wagyu and Angus, but the USDA requires that the animal be at least 50 percent Wagyu and remain in the feedlot for at least 350 days to receive these designations. In our taste tests, American Wagyu proved itself a delicacy worthy of an occasional splurge: It was strikingly rich, juicy, and tender.

I sometimes see meat at the supermarket labeled “lean” or “extra lean.” What do these terms mean?

These designations have pretty specific meanings, but this labeling isn’t required, so some very lean meat may not be labeled as such.

According to the USDA’ s Food Safety and Inspection Service, the terms “lean” and “extra lean” are used not only on beef but also on pork, poultry, and seafood to convey information about fat content, including the amount of total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol per 100-gram serving (about 3½ ounces). A “lean” designation means that the product contains fewer than 10 grams of total fat, 4.5 grams of saturated fat, and 95 milligrams of cholesterol per serving. “Extra lean” indicates fewer than 5 grams of total fat, 2 grams of saturated fat, and 95 milligrams of cholesterol per serving. (Following these rules, 93 percent lean ground beef would technically be considered “lean,” while “extra lean” beef would have to be more than 95 percent lean.) These designations can be used for any cut of meat as long as the packer includes nutritional information on the label. Whether they appear at all, however, is up to the individual packing company.

I just bought ham, and its label says, “water added.” What does that mean, and why am I paying for added water?

The label stems from a process called “wet curing,” in which ham is treated with a brining solution, affecting both its water and protein contents.

The USDA grades cooked ham products. “Ham, Water Added” is one of the four categories used in classifying ham. The others are “Ham,” “Ham with Natural Juices,” and “Ham and Water Product.”

Cooked ham is commonly wet-cured with a brining solution (often water, salt, phosphates or nitrates, and sugar). This makes the meat more seasoned and less likely to dry out when reheated at home. However, it also allows the producer to make more money by increasing the weight of the ham with water.

Officially, a cooked ham product is labeled by the percentage of protein by weight: The more water you add, the lower the percentage of protein in the meat. The USDA bases its grading scale on this protein percentage. Water-added ham has 17 to 18.5 percent protein by weight. We prefer ham with natural juices, which is 18.5 to 20.5 percent protein by weight and has good flavor and moisture when cooked.

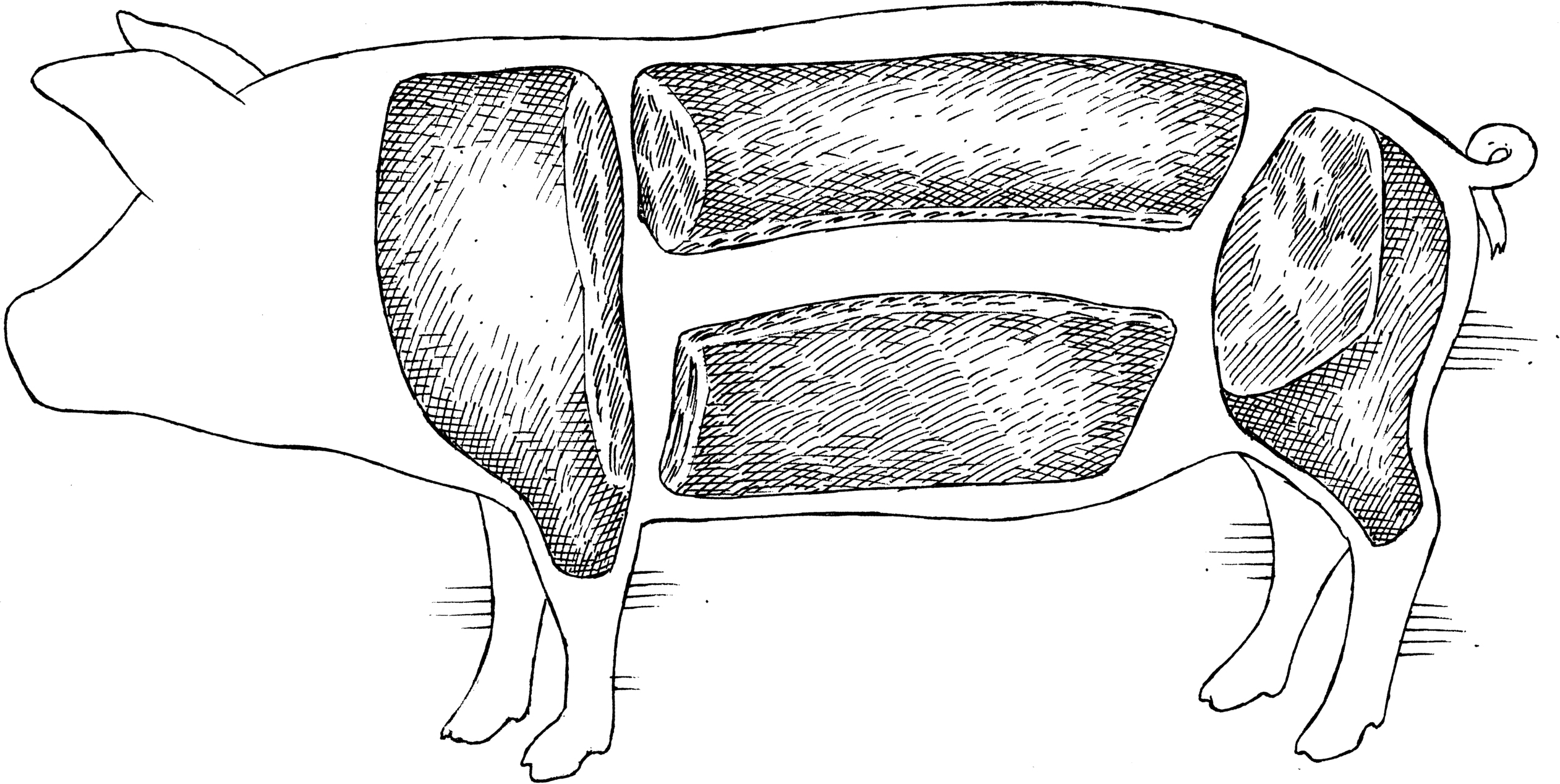

What is “enhanced” pork enhanced with? Is it better than regular pork?

We prefer natural pork to enhanced pork, which has been injected with a saline solution.

More than half of the fresh pork sold in supermarkets is now “enhanced.” Enhanced pork is injected with a salt solution to make lean cuts, such as center-cut roasts and chops, seem moister. But we think natural pork has a better flavor, and a quick 1-hour brine adds plenty of moisture. We recommend buying natural pork.

Manufacturers don’t use the terms “enhanced” or “natural” on package labels, but if the pork has been enhanced it will have an ingredient list. Natural pork contains just pork and thus doesn’t need an ingredient list.

What are nitrites, and why should I avoid them?

This additive can lead to the formation of carcinogenic compounds.

Cured pork products, such as bacon, often contain nitrite, a food additive that has been shown to form carcinogenic compounds when heated. So should you buy “nitrite-free” bacon? The problem is that while technically these products have no added nitrites, some of the ingredients used to brine them actually form the same problematic compounds during production. In fact, regular bacon contains lower levels of nitrites than some brands labeled “no nitrites or nitrates added” once the products are cooked. All the bacons we tested fell well within federal standards, but if you want to avoid nitrites you need to avoid bacon and other processed pork products altogether.

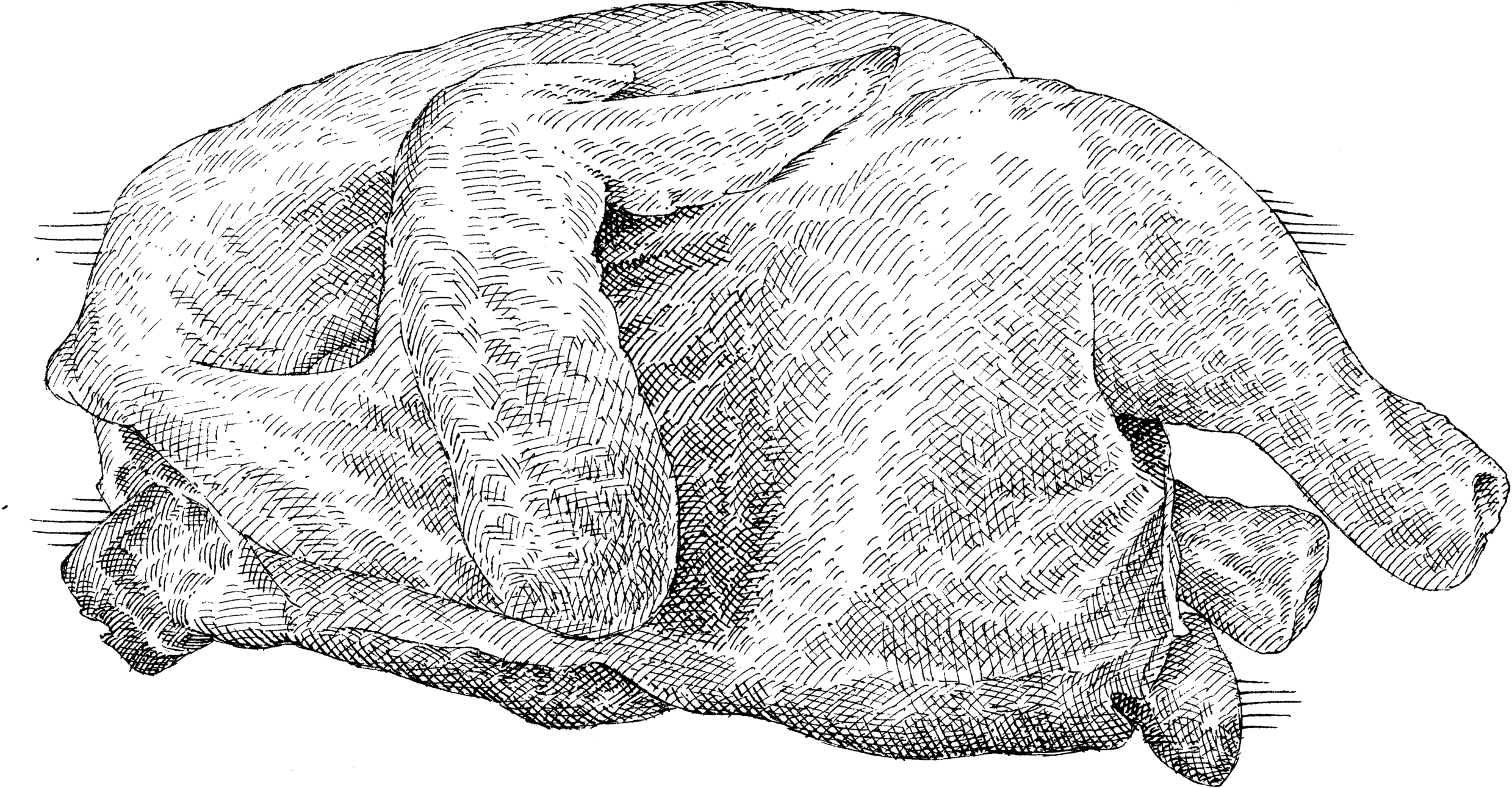

When shopping for whole chicken, I’ve seen “broilers,” “roasters,” and “stewing” birds. Can I really use them only for their assigned purpose?

Those labels give you some useful information, but that doesn’t mean that you have to do exactly as they tell you to.

These terms refer to the age of the bird—an important factor, since as chickens mature, they develop connective tissue that turns their meat tough. The older the bird, the more substantial the tissue, and the longer it takes to break down during cooking. However, since these terms are not widely used or understood, we call for poultry by weight, which is typically a good indicator of age.

Broilers (or fryers) are younger chickens: The USDA requires that the birds be slaughtered when they are around 7 weeks old and weigh 2½ to 4½ pounds. Next come roasters, processed at 8 to 12 weeks and weighing 5 pounds or more. Stewing chickens aren’t slaughtered until 10 months or older and typically weigh at least 6 pounds.

When we roasted and stewed each type, the mature hens were undeniably tough and chewy compared with the tender broilers and roasters. But after three hours of stewing, the stewing birds tasted even richer and were just as tender as the broilers and roasters, since their connective tissue had enough time to transform into gelatin, which lubricated and flavored the meat. Our recommendation: If you’re roasting, broiling, or frying, stick with a younger, more tender broiler or roaster. For a long-simmered stew or soup, it’s worth seeking out a stewing chicken (which, unlike broilers or roasters, may require special ordering).

What makes a “kosher” chicken kosher?

The process of koshering a chicken involves soaking, salting, and washing the chicken, as does brining; they just happen in a different order and for different reasons.

In accordance with the dietary laws that govern the selection and preparation of foods eaten by observant Jews, chicken is processed in a prescribed manner to make it kosher, or fit to eat. The primary function of koshering chicken (as well as other meats) is to remove blood, the consumption of which is prohibited by the dietary laws.

After slaughter, inspection, and butchering, kosher chickens are soaked in cool, constantly replenished water for a half hour and then set out to dry before being covered entirely—inside and out—with coarse kosher salt. The chicken is left to sit and drain for an hour, at which point it is rinsed three times to remove the salt. According to Dr. Joe Regenstein, professor of food science at Cornell University, when salt is applied to the surface of the chicken, the free-flowing liquid within the proteins is drawn out. The salt, in turn, is absorbed back into the proteins. The salt denatures, or unwinds, the coiled strands of proteins, thereby priming them for the absorption of more liquid when the salt is rinsed off. The water and salt molecules, tangled in the web of protein strands, are what make the koshered chicken moist and flavorful.

Brining essentially combines all these steps into one. Immersed in a large container of salt and water, the chicken (or turkey) goes through much the same process as a koshered bird. Liquid rushes out of the proteins to dilute the solution of salt, which is then absorbed back into the meat, causing the protein strands to unravel and eventually absorb and trap additional moisture. This moisture retention is the primary function of brining.

The chicken I buy is labeled “natural,” but what does that mean? Is it the same as “organic”?

“Natural” and “organic” are not the same. If you see the word “natural” on a poultry or meat label, take it with a grain of salt: The term has very little meaning.

While the term “natural” sounds nice, it doesn’t have much meaning on food packaging. The USDA stipulates that meat or poultry labeled “natural” can have no artificial ingredients added to the raw meat. It doesn’t cover how a chicken was raised, however, so a producer can tack the label on a package even if the animal was fed an unnatural diet, pumped with antibiotics, and/or injected with broth or brine during processing.

On the other hand, “USDA Organic” is a tightly regulated term. It applies not only to the meat itself but also to how the animal was raised. To earn this label, the animals must eat organic feed not containing animal byproducts, be raised without antibiotics, and have access to the outdoors.

What is the difference between “air-chilled” and “water-chilled” chicken?

As the names suggest, one is chilled in cold air and the other in cold water—and which process is used can have serious repercussions for the chicken’s flavor and texture.

When working on chicken recipes, we almost always use a high-quality bird from one of our favorite brands, Bell & Evans. One morning when these chickens weren’t available, we tested a recipe for roast chicken using a regular supermarket brand instead. The chicken behaved completely differently—the skin did not brown as much, and the meat tasted bland and washed-out. When we read the fine print on the label—“Contains up to 4% retained water”—we understood why.

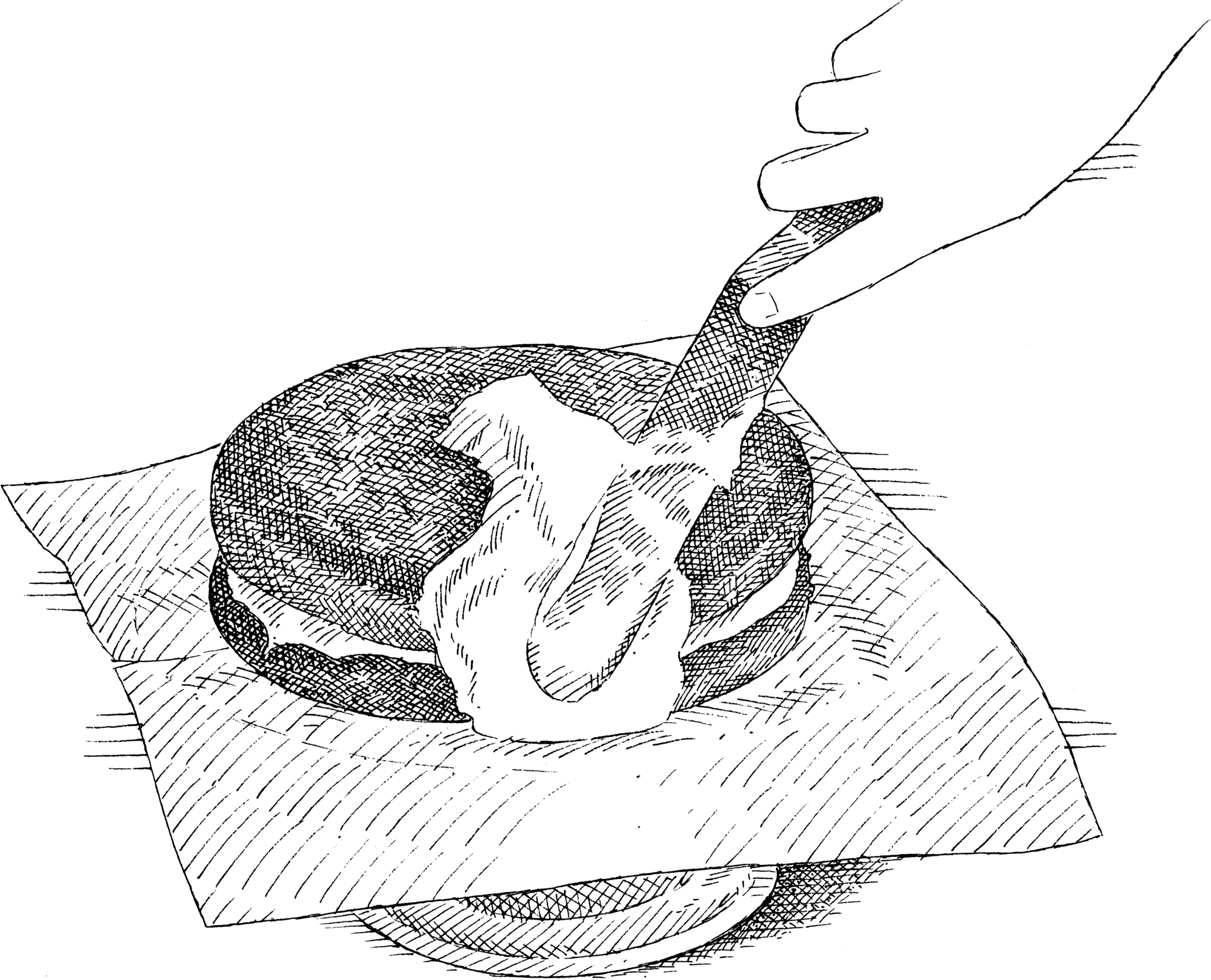

Unlike Bell & Evans chickens, which are air-chilled soon after slaughtering in order to cool to a safe temperature, most supermarket birds are submerged in a 34-degree water bath. According to the USDA’ s Agricultural Research Service, chickens can absorb up to 12 percent of their body weight in moisture during this process; the amount drops down to about 4 percent by the time they are sold. Air-chilled chickens, on the other hand, are not exposed to water and thus do not absorb additional moisture, which helps account for the more concentrated flavor of their meat and better browning of their skin.

My grocery store sells frozen “Atlantic salmon,” but the package says “product of Chile.” What gives?

“Atlantic salmon” refers to a species of salmon, not to the ocean where it was caught.

Atlantic salmon did originate in the Atlantic Ocean, but nowadays most Atlantic salmon sold in the United States is raised on farms in Norway, Scotland, Chile, and Canada. Similarly, Pacific salmon—which includes sockeye, coho, and Chinook (also called king)—originated in the north Pacific Ocean. Most Pacific salmon sold in this country is wild-caught in the American northwest, British Columbia, and Alaska and has a more assertive flavor and a lower fat content than farmed Atlantic salmon.

Because of france’s rich and influential culinary culture, you will encounter a lot of French terms at restaurants, in cookbooks, and on food packaging. This handy guide will help you avoid confusion and embarrassment the next time you’re out to eat with your foodie friends or navigating the gourmet market.

| Word/Pronunciation | What It Is |

| aïoli aye-OH-lee |

Aïoli is a rich mayonnaise sauce infused with garlic, although other flavorings are sometimes used. It is served as a condiment for meats, fish, and vegetables or spread on sandwiches. |

| à la mode ah luh MOHD |

Literally translated, this phrase means “in the latest style or fashion.” It usually refers to a dessert served with ice cream. |

| aperitif uh-pair-ih-TEEF |

An aperitif is an alcoholic drink that you have before the meal to stimulate the appetite. The opposite of an aperitif is a digestif, which you drink after the meal to aid in digestion. |

| bain-marie bayn-muh-REE |

A hot water bath called a bain-marie is used to gently cook delicate foods like custard by modulating the heat of the oven. |

| béarnaise bare-NAYS |

This classic French sauce is a variation on hollandaise. Both are buttery, creamy emulsified sauces, but béarnaise has a slightly more savory flavor profile due to the addition of white wine and tarragon. It is frequently paired with steaks, chops, and fish. |

| béchamel BAY-sha-mell |

The classic French white sauce is traditionally made by stirring milk into a cooked mixture of butter and flour, or roux (see here). It serves as the base for numerous dishes such as lasagna and creamed spinach. |

| confit kon-FEE |

The confit cooking method involves slow-cooking food in abundant fat until the food is completely tender. Traditionally used for duck and other meats, this method can also be applied to ingredients such as garlic or mushrooms. |

| crème Anglaise krem ahn-GLAYS |

This velvety custard sauce is served with fruit, fruit desserts, cakes, and puddings, including sticky toffee pudding. |

| croquette kro-KET |

A croquette consists of food (such as minced meat, fish, or vegetables) shaped into a small ball. Croquettes are often breaded and deep-fried. |

| dacquoise da-KWAZ |

A dacquoise is a multilayered pastry dessert made from meringue, buttercream, and chocolate ganache. Its name means “of Dax,” the town in southwestern France where the dessert was first made. |

| demi-glace DEH-mee-glahss |

Demi-glace is a highly reduced sauce base with rich, concentrated flavor and glossy texture. |

| en papillote enh pah-pee-YOTE |

This cooking method is characterized by enclosing the food in a parchment paper packet before cooking. The food steams in its own juices for pure, clean flavors. |

| fleur de sel fluhr deh SELL |

This flaky, crunchy sea salt (literally “flower of salt”) is made by skimming off the thin film of salt that forms on seawater. It is often used as a finishing salt. |

| haricots verts AH-ree-coe vair |

While the literal translation of haricots verts is just “green beans,” this name refers to a particular type of thin French green beans. |

| hors d’oeuvre or DERV |

Literally translated, this phrase means “outside the work”—it refers to food that is “outside” the main meal, or food served before the meal. These small appetizers, often finger foods, are usually savory. |

| mille-feuille meel-FWEE |

A mille-feuille is a type of dish made by layering puff pastry and filling. It can be savory or sweet. The name literally means “thousand sheets,” although most recipes do not actually have a thousand layers. |

| mirepoix meer-PWAH |

Mirepoix is a mixture of onions, carrots, and celery that serves as a flavor base for stocks, broths, sauces, and braises. The classic ratio is 2 parts onions, 1 part carrots, and 1 part celery. |

| mise en place meez uhn PLASS |

This term for the process of preparing and measuring out all the ingredients for a dish before you begin to cook means “putting in place” in French. |

| pâte à choux pat ah SHOO |

This light, basic pastry dough is used to make the base of profiteroles, eclairs, cream puffs, and gougères. You may also see the terms pâte brisée (shortcrust pastry, as used in a pie) or pâte sucrée (sweet pastry, as used in a tart). |

| persillade pur-see-YAD |

Persillade refers to a mixture of finely chopped parsley and garlic that is commonly used to garnish meat or vegetables. |

| rémoulade ray-moo-LAHD |

This creamy, tangy sauce usually contains capers and herbs and is traditionally paired with fish and shellfish. |

| sablé sah-BLAY |

Sablés are French butter cookies similar to shortbread. |

| sous vide soo VEED |

During sous vide cooking, vacuum-sealed food (the name literally means “under vacuum”) is cooked in a water bath that is heated to the food’s final serving temperature (e.g., 125 degrees for salmon). |

| terroir tehr-WAHR |

Terroir describes the way that the unique place in which a food was grown can affect its flavors. It is frequently used to describe wine but can apply to many other kinds of natural products. |

| velouté veh-loo-TAY |

This classic, rich French sauce is made from stock, cream, butter, and flour. |