Consistent and appropriate care of the foot is a critical component of horse health.

The old saying, “no foot, no horse,” couldn’t be more true. There is a clear relationship between the working ability of the horse and the soundness of his hooves.

If you handle a horse’s feet often, he grows accustomed to it as part of his daily routine. He learns to mind his manners for trimming and shoeing. With frequent handling, you become more apt to notice problems. As you clean his feet daily, you can remove any rocks stuck in the feet and prevent buildup of packed mud or manure that can lead to thrush. You are also likely to notice wounds or any heat in the leg or hoof (or swelling of the lower leg) that could be a sign of infection or injury.

Because the horse is an athlete, his feet and legs are crucial parts of his structure. Care of the feet is essential; neglect can lead to unsoundness and pain.

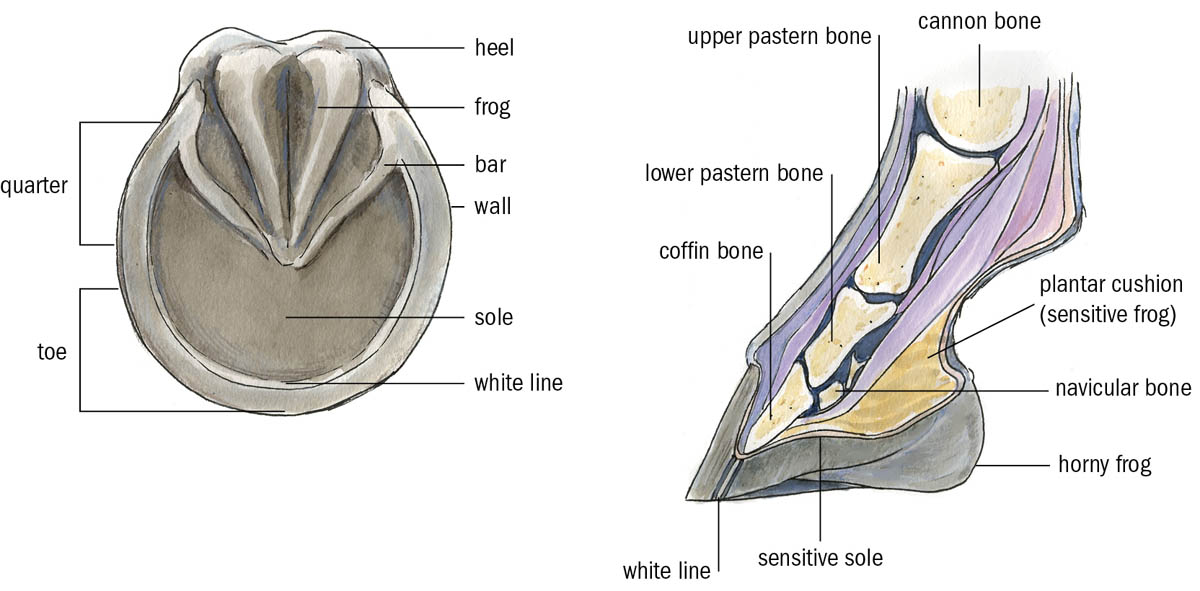

Horses are individuals; each one’s feet differ slightly in shape, hardness, and rate of hoof growth. The hoof is a specialized horny shell that covers sensitive living tissues — bones, blood vessels, and nerves. The outer shell is a unique covering that grows continuously to compensate for wear and tear.

The sole should be somewhat concave to allow for expansion when weight is placed on it. The hoof wall is designed to carry most of the weight and the bars serve as a brace to prevent overexpansion or contraction of the foot. The V-shaped frog serves as a cushion in the middle of the foot, helps absorb concussion, and regulates hoof moisture. If any of these outer tissues are injured or abused by excessive trimming, the normal functions and soundness of the hoof are impaired.

How the foot is built plays a role in its ability to hold up. Front hooves should be larger, rounder, and stronger than hinds because front legs support about two-thirds of the horse’s weight. Hooves should be wide at the heels, not narrow or contracted. The sole should be slightly concave in the front feet and even more so in the hinds. A horse with flat feet is likely to suffer stone bruising or develop navicular disease. (See chapter 9 for more information.)

Ideally, the hoof wall should be thick, pliable, and resistant to drying out, and should grow at a normal rate. The sole should be thick so it can’t be easily bruised, and the bars should be strong and well developed. The frog should be large and healthy and centered in the foot. An off-center frog is an indication of crooked feet and/or legs; the hooves probably do not wear evenly.

Few horses have perfect feet and legs. When breeding horses, you should select individuals with the best possible conformation because this characteristic is passed on to offspring. When acquiring or keeping a horse with less than ideal feet, you may decide to overlook the foot faults. In spite of a foot problem, plenty of folks have purchased or held on to a child’s dependable old horse or pony, or an animal with malformed feet because of an earlier injury, or a horse purchased for his wonderful disposition or exceptional ability. These horses may need special foot care or more than routine foot trimming to stay comfortable and reasonably sound.

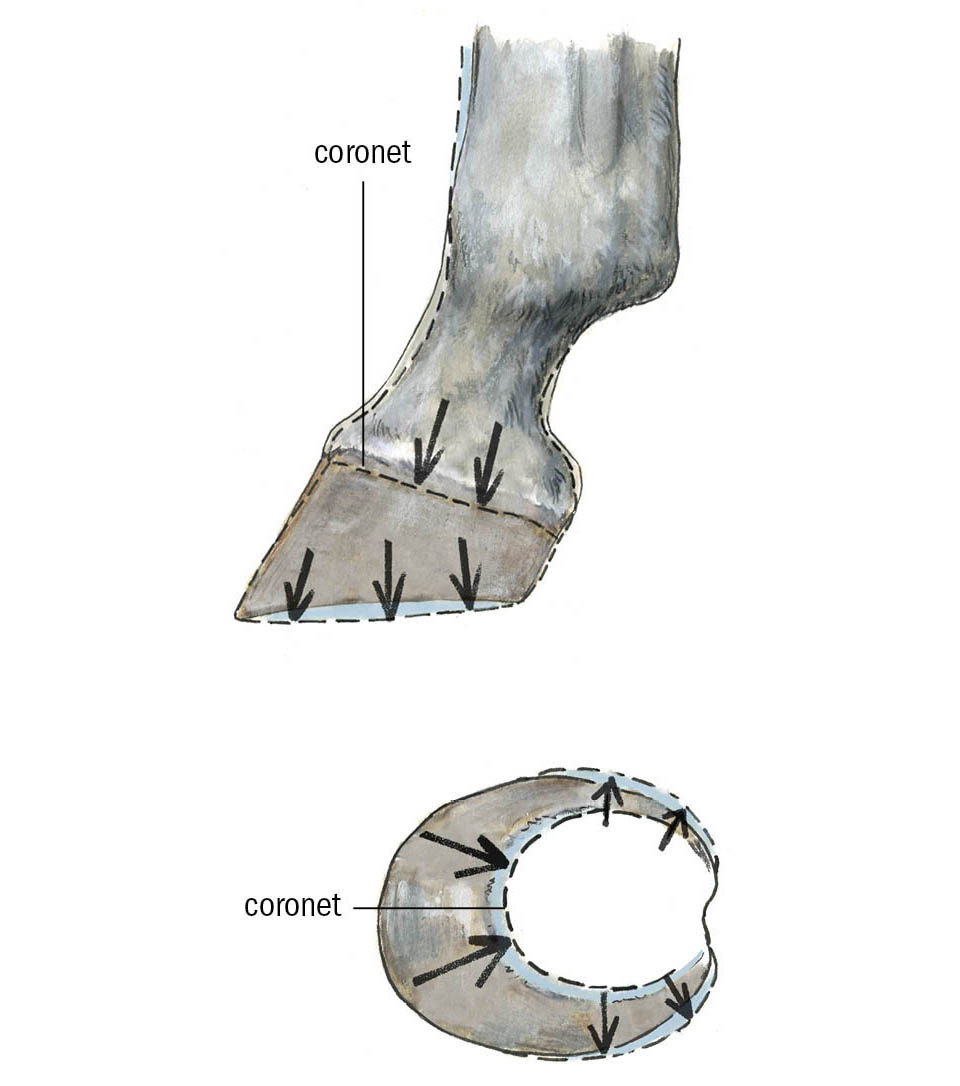

A contracted foot is narrower than normal, especially at the heels and quarters; the frog becomes small and atrophied, shrinking to such an extent that it no longer has contact with the ground. A horse with contracted heels or feet is likely to go lame because of the inability to properly absorb and dissipate concussion — making him susceptible to problems such as navicular disease or concussion-related breakdowns in other structures of the foot and leg.

Contracted heels are often caused from improper shoeing (the shoe too narrow at the heels with no room for hoof expansion when weight is placed on the foot), injury, a diseased frog, or unnecessary shoeing — leaving shoes on too long or keeping the horse shod year-round. If shoes are left on too long without trimming the foot and resetting the shoes, the hoof wall grows long and heels become underrun, inhibiting expansion at the heel and quarters.

Lameness from any cause may make a horse put less weight on a foot and, over time, the lack of frog pressure results in contraction. Once a foot is badly contracted, it may take more than a year to become normal again, even with special shoeing.

Contracted feet are more common in front feet than hinds, especially if the condition is from improper shoeing. Sometimes only one foot is contracted because of an injury. It is easy to tell the difference between the normal foot and the contracted one: the normal foot has a healthy frog and heels whereas the heels of the contracted foot are too close together.

Foot contraction is often accompanied by a dished or concave sole. The foot no longer flattens when weight is placed on it because the heels cannot expand; the sole becomes more concave, arched upward. If contraction becomes severe, the hoof wall may start to press against the coffin bone inside the foot, making the horse lame and unsound — a condition called hoof-bound.

Treatment. Corrective trimming and shoeing can help reverse contraction (with the help of a good farrier), but the primary cause — such as lameness, improper shoeing, or dry feet — should be identified and corrected. If feet are hard and dry, use a good hoof dressing daily to restore proper hoof moisture. A dry foot lacks elasticity for proper foot expansion.

Normal foot (left) and contracted foot (heels too close together; frog small and atrophied)

Foot expansion helps counteract concussion; the normal foot has a concave sole that flattens when weight is placed on it, the heels springing wider apart. The coronet narrows and drops backward as the overall height of the foot decreases.

Flat feet lack natural concavity of sole — an inherited condition. There is not much you can do to correct this, but you can keep the horse from stone bruising by using Easyboots or some other brand of protective hoof boots over the shoes when riding among rocks or by having your farrier attach hoof pads under the shoes.

Some flat-footed horses get by without hoof pads if the soles are kept toughened so they don’t bruise easily. This can be done by applying a little iodine or commercial hoof-hardener product over the sole of the foot, taking care not to spill any of it on the horse’s skin (because it burns) or let it run over the hoof wall (because it dries out the tissues). The iodine can be applied on days when the horse will be traveling on rocks or gravel.

A club foot is one that has a steep pastern, with hoof and pastern angle of more than 60 degrees. The hoof angle is often steeper than the pastern angle, and the heels grow faster than the toe. If just one foot is this way, it may be because of an old injury (lack of use can cause contracting and shortening of the tendons, making the foot more upright). Sometimes the problem is genetic; in certain family lines, several individuals may have one abnormal foot (always on the same side), possibly because of conformation of that leg and the way the foot and pastern grow. Other horses may inherit the club-foot trait in both fronts. This disability makes a horse less agile, with a rough and stumbling gait.

Treatment. Frequent and proper foot trimming can help a horse with a club foot, especially if corrective trimming begins while he is still young and growing, before the condition gets worse. Letting the hoof grow too long between trimmings can aggravate the problem, causing the horse to have a very long heel and upright foot and pastern.

Club foot (left) compared with normal foot (right)

You may wish to leave all foot trimming to your farrier; however, if your horses have normal feet and legs and do not need corrective trimming or special work, you may wish to learn how to trim. Ask the farrier to give you lessons on trimming so you can take care of the routine matters. Even if you never trim a foot yourself, be sure to handle and clean all feet regularly. Then you’ll know if there are any problems and be able to appropriately schedule trimmings with the farrier.

When cleaning a foot, a hoof pick or the blunt edge of a hoof knife is the best instrument for getting out all dirt or embedded rocks. Never use a very sharp or pointed object for cleaning a foot. You could injure yourself or the horse if he happened to jerk his foot at the wrong time.

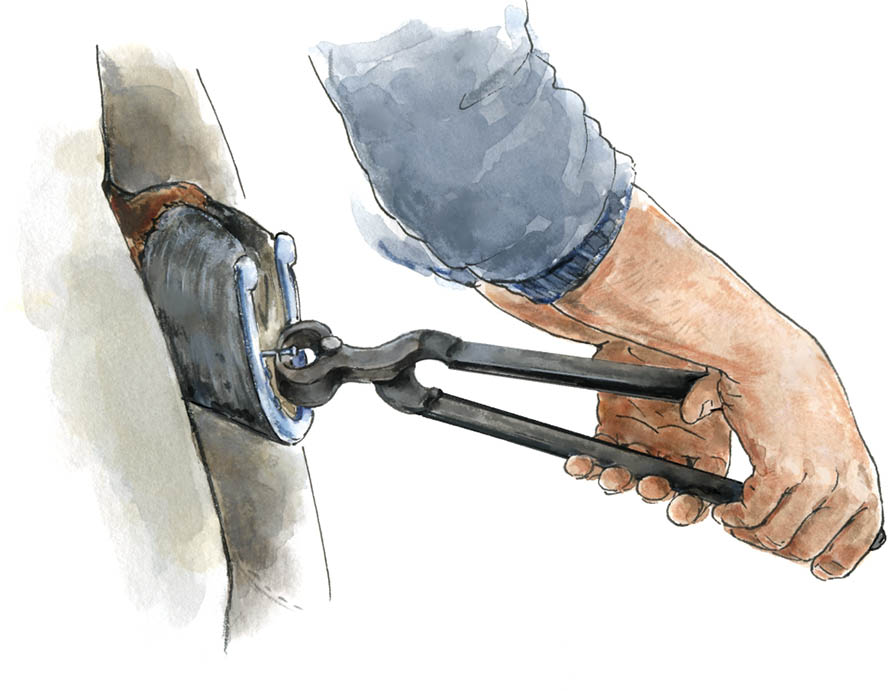

Once in a while, it becomes necessary for a horse owner to pull off a shoe. Even if a farrier does all your trimming and shoeing, you may, at some time, face a situation when you can’t wait for him or her. Even if the shoe was well clinched to start with, it may become loose — get hooked on a fence, caught in a deep bog, stepped on by a hind foot and pulled loose, or loosened when traveling through rocks.

Use a hoof pick to clean feet, not a screwdriver or other sharp implement.

In these instances, it’s best to pull off the shoe. If it is not immediately removed, it may injure the horse if it’s hanging loose on one side, or it catches on something, or causes a corn or bruise because it is putting pressure on the sole or bars. If the shoe is accidentally pulled off, it may break the hoof wall, taking out a chunk and making it harder for the farrier to reshoe the foot.

The shoe is easiest to remove (and pieces are less likely to break out of the hoof wall as you pull it off) if you first unclinch the nails that are still holding. You can use any kind of hammer to drive the clinch cutter or screwdriver under each nail end to pry up the clinched end and straighten it out. This is easiest while the horse’s foot is on the ground. Be careful not to cut into the hoof wall if you are using a screwdriver. Once each nail is unclinched, cut off the straightened nail end with nippers if you have any. If you don’t have a clinch cutter or screwdriver, rasp off the clinched nail ends with a rasp or file.

If you don’t have a rasp or file, you can still pull the shoe with nippers or vise grips, especially if the shoe is already partly loose. Hold the hoof in regular shoeing position — between your legs for a front foot, across your thigh for a hind. Place the nippers or vise grips between shoe and hoof at the heel (starting on the looser side to make it easier), and use a downward force, pushing the handles slightly toward middle of the foot, to pry and loosen the shoe. Work alternately along each branch of the shoe, starting at the heels and moving toward the toe as the shoe comes loose.

If you are unable to undo the clinches, you can still remove the shoe in this manner, although it takes a bit more strength and leverage because you must pull the clinches loose and on through the hoof wall. The nails will straighten out as you pull the shoe; they will come out with it.

If some of the nails are still tight, the hoof wall may break unless you take each nail out as you go. This may happen when you pry on the shoe because the clinches are still secured in the wall. To get hold of a nail head, you may have to gently pound the shoe back down against the hoof so the loosened nail head protrudes up enough to grasp with hammer claws, nippers, or pliers. Pull it out, then loosen the shoe enough to take out the next nail, alternating down each side of the shoe.

1. Pull a nail out to help loosen the shoe.

2. Work down each branch of the shoe with alternate pulls and take each nail out as you come to it.

3. Pull the shoe.

For many horses, going barefoot can be healthier than having shoes on all the time. Whether a horse is a good candidate for leaving shoes off depends on the horse’s lifestyle, use, hoof conformation, and so on. For feet to be healthy and strong while barefoot, the horse must be in a natural environment — reasonably dry ground rather than continually wet areas — with room to exercise. A horse kept in a stall can’t keep his feet as healthy and strong as the horse roaming a 300-acre rocky pasture. The latter will be wearing his feet normally, about the same speed they grow, and getting regular exercise that aids the blood supply to the hoof.

The more nearly a horse can approach totally natural conditions, the healthier his feet will be. Barefoot life won’t work for a horse who is confined or kept in a wet pasture where his feet stay soft. A horse with soft, bare feet will quickly go tender-footed or lame from bruising if you try to ride him on a gravel road. However, if you allow his feet to toughen gradually — put him in a drier, larger area and limit your rides to very short distances at first — and he’s not ridden excessively on rocky ground, he may get by just fine without shoes. There are many styles of hoof boots available for extra protection during rides.

Bare feet must also be properly balanced so the hoof walls on each side bear equal weight and stress and the toes are not too long. Otherwise, the hoof walls will split and crack from abnormal pressures. Many horses must be kept shod to keep the foot from cracking and chipping, and to keep the wall from wearing away too fast if the horse is ridden regularly on rocky ground.

Thrush is an infection of the frog, caused by bacteria (and sometimes fungi) commonly found in barnyards or pastures. Because these organisms thrive in wet, decaying material such as manure or mud, thrush is common in horses who live in muddy pens, wet pasture, or dirty stalls. If a horse’s feet are frequently packed with dirt, mud, or manure, the lack of air next to the frog and the constant moisture in the hoof make ideal conditions for the organisms to flourish, rotting the frog tissue.

The telltale foul odor of thrush is unmistakable when you clean a horse’s foot. There are also black secretions along the edges of the frog, and it may be soft and eaten away at the edges. The early stages of thrush are indicated by just a little dark coloration and grime around the frog, or dark spots along the white line of the sole, plus the bad odor. You can quickly clear up the problem at this point by keeping the foot cleaner and applying iodine, bleach, or a commercial preparation for thrush daily to the affected area to kill the bacteria. Just be careful not to let any of these medications run down the hoof wall to the coronary band or they may burn the skin.

If a horse is kept in a muddy pen, boggy pasture, or dirty stall, and his feet are rarely cleaned —never having a chance to dry out — thrush can progress to the point of lameness as the infection penetrates and spreads to sensitive parts of the foot. If thrush is long-standing and deep, the horse will flinch when his feet are cleaned or trimmed because the frog is undermined with infection.

Prevention is the best “treatment”: keep the horse in a clean environment, clean his feet often, and ride or exercise him regularly. If he can get out of the wet paddock and travel on dry ground, his feet will have a chance to dry out and air will get to the bottom of them, inhibiting thrush. No hoof dressing or medication can keep thrush from recurring if the horse is constantly kept in dirty surroundings and his feet are packed with mud and manure most of the time.

If you detect the beginnings of thrush when you clean a foot, don’t ignore it. Clean the foot thoroughly, then swab the affected areas (usually the edges of the frog and any black spots in the sole) with iodine-soaked cotton or squirt on a little iodine with a small syringe. Daily treatment with strong (7 percent tincture) iodine for three or four days will clear up an early case. Clean feet often and keep track of their condition — then, thrush won’t get a head start.

This is the common term for a progressive infection and subsequent separation of the hoof wall resulting in the wall coming loose from the foot. The term “white line disease” is misleading, however, because the area of the hoof affected is the layer just beneath the outer hoof horn, not the white line (which is the bottom of a more inner layer at the junction of the sole and hoof wall).

The problem usually starts at the bottom of the foot at the white line between sole and wall and travels upward, creating a hollow area between wall and foot. Earlier terms for this condition were “seedy toe” and “hollow hoof.”

The cause of this problem is opportunistic pathogens (often a mix of anaerobic bacteria and fungi) that “eat” hoof horn, entering the foot through damaged tissue. If the foot is out of balance or too long, with a flare on one side or a dished toe, the extra stress on the hoof wall may create a separation at the white line. Each time the horse places weight on the foot, it stretches the white line area, enabling the fungal spores or bacteria to enter. They may also enter through any break in the hoof wall, or through an old abscess.

These hoof-eating pathogens thrive in an airless environment and become established in the area between the outer wall and the inner, sensitive tissues and gradually eat it away. Tapping the outside of the hoof produces a hollow sound. The hoof horn residue inside this area is like chalky, dry, crumbled cheese. If a lot of the inner wall is damaged, the foot loses some of the attachment that binds the coffin bone to the hoof wall, and that bone may drop, just as it does in severe cases of laminitis (founder).

The only successful way to treat white line disease is to trim out all the diseased tissue to get rid of most of the microbes. Topical medication can be applied to get rid of the rest. You will probably need help from your farrier, especially if much of the hoof wall must be cut away. The area must be opened up to the air because these microbes thrive in an airless environment. If the hoof wall attachments have been so seriously damaged that the coffin bone moves, the horse will need special shoeing for support. If caught early, white line disease is fairly easy to treat and clear up; however, in advanced cases in which a lot of the wall must be cut away, it may take six months to a year for the horse to grow a new hoof wall. Those horses may need the foot to stay in a special boot or wall cast to protect it until they can grow more wall.

White line disease can be prevented by keeping the feet well trimmed (not too long) and in proper balance so there are never any extra stresses on the foot to stretch or damage the white line. Because some horses tend to get repeated infections, once the problem is cleared up, your farrier may recommend soaking the feet every couple of months or so in a product containing chlorine dioxide. Studies have shown this treatment to be most effective against redevelopment of this fungal or microbial infection. Since these microbes can be transmitted from one hoof to another, farriers should disinfect their trimming and shoeing tools after working on a horse with white line disease.

The horse’s foot is strong and durable, but it can be injured if he steps on a sharp rock or nail. The tough outer covering of hoof wall and sole protect the delicate inner tissues from most types of trauma, but sometimes an exceptionally deep penetration, severe blow, or constant pressure causes bruising of the underlying tissues.

Corns are bruised areas on the sole, usually involving the tissues at the angle where the hoof wall meets the bars. A corn appears as a slightly reddened area and is especially noticeable when feet are trimmed and the sole pared down. The red area may be hot and tender in the early stages of the bruise. Corns are most common in front feet because they bear more weight and are more subject to bruising than are hind feet. Horses with flat feet are more likely to get a corn or sole bruise from stepping on sharp rocks or gravel.

Corns are most often caused by improper shoeing (ill-fitting shoes that are too narrow) or by leaving shoes on too long. The hoof wall begins to grow down around the outside of the shoe at the heel area, and the shoe puts pressure on the sole at the angle between hoof wall and bars, bruising the sole. Trimming a horse’s heels too low may also cause corns as a result of increased pressure at the angle of the wall and bar. Corns in this area are rare in a horse who goes barefoot, but he may suffer sole bruising (a similar sore spot) from stepping on rocks. Horses with thin soles or chronic laminitis (founder) with dropped soles are very susceptible to sole bruising. Bruises in the sole generally occur in the toe or quarter area.

Corns or sole bruises can make the horse lame. If the problem is a corn, the horse will favor the heel and put more weight on the toe. If the problem is a bruise in the toe area, he will try to land on his heel to keep the weight off his toe. Your veterinarian or farrier may use a hoof tester to locate the corn or bruise. The horse will flinch when the sore area is pressed. If the sole at that spot is pared down with a hoof knife, a reddish (or bluish if an abscess is developing) discoloration may be seen in the area where the horse shows pain.

When improper shoeing causes corns, removal of shoes may be all that is necessary for healing. The horse should not be ridden or reshod until the corn and lameness have disappeared. To make sure shoes do not cause corns, check that the heels of each shoe extend well back and cover the hoof wall completely at the heel and quarters to allow room for hoof expansion. The hoof wall in this area must rest on the shoe. If the hoof extends beyond the shoe when the foot expands, the shoe is not large enough.

If a horse develops an abscess from a corn or sole bruise, your veterinarian will pare down the sole at that area until the infection in the sensitive tissues begins to drain. Then soak the foot daily, packing and protecting it between soakings, as you would for a puncture wound.

Puncture wounds in the body are always serious because they can lead to tetanus if a horse has not been vaccinated, but a puncture in the foot can be very bad because it may damage the inner tissues and cause any one of several serious problems — inflammation or fracture of the coffin bone, decay of the bone, or decay of the digital cushion (the spongy area above the frog). A puncture in the middle third of the frog may puncture the navicular bursa.

A puncture in the bottom of the foot is not always easy to locate if the foreign object (nail, stick, or rock) is no longer embedded. A puncture in the frog can be difficult to find if the spongy tissue has closed up again after the object makes its hole.

If you suspect a puncture (or the object is still embedded), consult your veterinarian. You may not realize there is a problem until an abscess develops within the foot and the horse goes lame — from infection putting pressure on surrounding tissues. It’s best to start treatment immediately after the puncture occurs.

An abscess may be caused by a puncture wound, an infected stone bruise, a misplaced horseshoe nail that quicked the hoof (entered the sensitive inner tissues), or a case of deep, neglected thrush that penetrated into sensitive inner tissues. Sometimes, a hoof crack becomes deep enough to allow entry of bacteria that start an infection.

The area should be opened to drain, soaked, cleaned with disinfectant, and the hole plugged with a wick that will allow drainage. A puncture wound in the sole should be opened so there is at least a 1⁄4-inch (0.6 cm) hole into the infected tissue, with the walls of the drainage hole widening toward the ground surface of the sole so it won’t become obstructed. When the wound is in the frog, trim away the frog at the site of the puncture to establish adequate drainage for the abscess.

Part of the treatment for a puncture wound or foot abscess consists of soaking the foot. After the veterinarian has dealt with the original condition — opening the area for drainage and flushing it out — and given the horse a tetanus shot and possibly antibiotics, he may tell you to soak the foot daily for several days to draw out infection and promote rapid healing. Soaking the foot in a warm water-and-salt solution not only pulls out any remaining infection but also makes the sore foot feel better.

Soaking a Foot. If a horse has never had a foot soaked, get him used to the idea carefully and gradually so it will be a good experience — so he will cooperate rather than resist. Put his foot gently into an empty rubber tub. Once he stands there with his foot in the tub, wash the foot thoroughly with water — scrubbing with a rag, if necessary, to remove mud or dirt — and replace it in a clean, well-rinsed tub. Carefully add a little warm water, slightly warmer than the horse’s body temperature (100°F [37.8°C]). After he accepts it and is relaxed, you can add several tablespoons of Epsom salts (magnesium sulfate) to the water. Don’t add the salt to the water until you’re sure he’s comfortable about the soaking in case he moves around and spills the first batch.

After he’s standing with his foot in the warm salt solution, periodically add hotter water until the water in the tub is quite warm but not burning hot. Keep the water as warm as the horse will tolerate. It’s easiest with two people — one to keep the horse from spilling the tub water if he picks up his foot (hold the foot and guide it gently back down into the water so he won’t put it on the ground and get it dirty), and one to manage the tea kettle and refills. Usually 20 to 30 minutes of soaking per day is adequate. Most infections clear up after three or four days of this.

Soaking a foot can be simplified by using a special soaking boot that can be filled with warm water and Epsom salts. The horse can move around with the boot and there’s no danger of spilling a tub.

Protecting a Drainage Hole. If there is a drainage hole in the sole or on the bottom of the foot, protect it between soakings by wrapping and bandaging the foot to keep out mud and dirt. An easy way to bandage is to wind vet wrap (stretchy material that sticks to itself) around the foot to cover the bottom, then use duct tape from mid-hoof on up to the pastern to hold everything in place. Then put the bandaged foot into an Easyboot or some other type of protective boot so the bandage stays clean and dry. If the horse can be kept in a clean stall, a treated abscess will often heal well enough so that you can turn the horse out again in three to four days. If you don’t have a stall and the horse’s pen or pasture is wet or muddy, use a waterproof boot to keep the foot and bandage clean between soakings.

Sometimes a horse suffers injury to the coronary band at the top of the hoof by running into something, stepping on himself with a shod hoof, or being stepped on by another horse. A deep wound at the coronary band that results in scar tissue may disrupt the hoof-growing cells and make a weak spot in the hoof as it grows — an area that may easily crack or disrupt hoof growth completely.

An Easyboot or similar product can help keep the foot clean and dry.

A serious or deep injury at the coronary band requires immediate veterinary attention so it can heal properly and prevent proud flesh (excessive granulation tissue; see chapter 16).

Occasionally, a crack develops in the hoof wall from splitting and chipping, concussion, or injury. Barefoot horses often develop chips and cracks, but these are usually not serious unless neglected. In a long, untrimmed foot, cracks can become worse quickly, traveling up into sensitive tissues. These can be hard to correct. A deep crack may make the horse lame.

Toe cracks, quarter cracks, and heel cracks start in the hoof wall at ground surface, usually from a chip or split in an overly long hoof, and travel upward. Sometimes, a crack starts in the heel or quarter area and travels horizontally around the foot because of weakness in the wall at that area (from a blow or injury, as when a horse strikes the hoof against a rock). Sometimes, a crack starts at the coronary band. This type of crack travels downward because of weakness in the hoof wall at that area.

A barefoot horse with a serious crack must be trimmed often to relieve pressure on the crack and keep it from splitting further. It is difficult to grow out a bad crack on a barefoot horse because it’s impossible to take all pressure off the crack and keep it from spreading. The horse may have to be shod.

When trimming a foot with a crack, the farrier will cut away the hoof wall at the ground surface of the crack so it does not bear weight (which would expand the crack). He may also try to stop the progress of the crack by burning a small notch across its highest point with a crescent-shaped iron. This helps stop the splitting because, if weight is placed on the crack, it sends the force along the notched groove instead of up the hoof wall. Some farriers lace the sides of the crack together with wire, to keep it from opening up and spreading on up the hoof.

Corrective Shoes. A crack that originates in the coronary band caused by an old injury that affects horn growth may be a more persistent problem. In this case, corrective shoeing may be necessary for the rest of the horse’s life. Regular use of a hoof dressing, lanolin ointment (such as Bag Balm or Corona), or olive oil may keep the coronary band and hoof wall more pliable in that area and less apt to crack.

A shoe can help take the stress off the hoof wall and keep a crack from splitting further, enabling it to grow out. A clip on each side of the crack helps keep the hoof from expanding there when weight is placed on the foot.

Fast-Drying Glue or Plastic. Some cracks can be repaired with a strong, fast-drying glue or plastic that fills the hole and holds the cracked area together so it can’t keep expanding. This protects sensitive tissues from contamination and infection if the crack is large or deep. There are several types of acrylic bonding agents that your farrier or vet may use for repairing cracks. The foot will still need to be trimmed often or the shoe reset — until the crack grows out — so the glue or bonding agent may have to be reapplied several times.

Pain is nature’s way of keeping an animal off an injured leg or foot. If a horse limps, try to determine the cause. A sore front leg (or foot) will cause him to bob his head more than normal as he hurries to get off the painful limb and takes more weight on the good leg. A sore hind leg or foot will cause a hitch in his stride as he puts less weight on the bad one and hits the ground harder with the good one.

To tell which leg is lame, watch his head and hips. The horse’s head goes higher when he steps on the bad front leg and drops lower as he takes more weight on the good front leg. His hip stays higher on the lame side if he’s got a bad hind leg and drops lower on the good side that is taking more weight.

Check his feet and legs to see what the problem might be. It may be as simple as a rock caught in his foot, or it may be a stone bruise or leg wound. If there is infection in a leg, there will be heat and swelling. A pulled tendon or injured joint will also cause heat and swelling. If you cannot determine the exact problem or how to treat it, call your veterinarian.