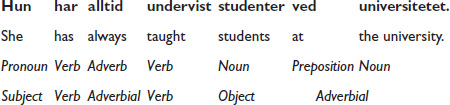

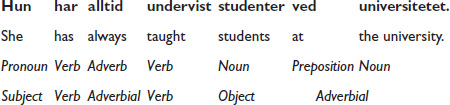

In Chapters 1–9 of this book we largely examine word classes and the way some words inflect and are used. In the current chapter, we look at the syntax of Norwegian, that is how words are combined into longer phrases, utterances, clauses and sentences. By way of comparison, compare the main clause sentence below, analysed first by word classes and then by clause elements:

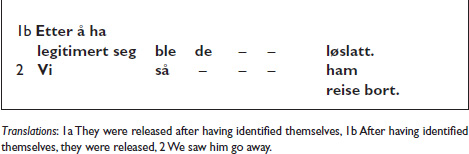

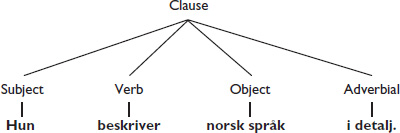

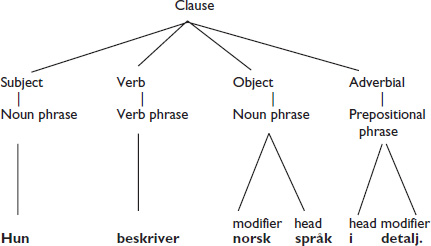

The clause is one of the basic elements of sentence structure or syntax. It comprises clause elements as in the diagram below:

She describes Norwegian language in detail.

These clause elements consist of phrases. Phrases in turn comprise a head word alone or a head word and modifier. The structure of the clause can in this way be regarded as a hierarchy:

Phrases comprise a head word alone (H) or a head word with modifiers coming before or after the head:

|

Noun phrase |

Verb phrase |

tre jenter fra Tromsø |

nesten måtte gi opp |

H |

H |

three girls from Tromsø |

almost had to give up |

Adjective phrase |

Adverb phrase |

mye eldre enn henne |

nesten aldri |

H |

H |

much older than her |

almost never |

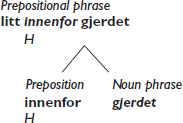

Prepositional phrase |

|

litt innenfor muren |

|

H |

|

a little way inside the wall |

Noun phrases may alternatively contain a pronoun as head (see also 10.2.2):

hun med det lyse håret |

she with the fair hair |

H |

The verb phrase in a narrow sense comprises the finite verb plus optionally a verb particle or reflexive pronoun: klarnet opp, ‘cleared up’; snu seg, ‘turn around’.

The infinitive phrase comprises an infinitive (and complements): ikke å glemme passet, ‘not to forget the passport’.

The prepositional phrase consists of a preposition plus (optionally) a noun phrase:

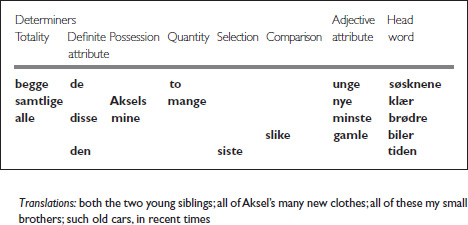

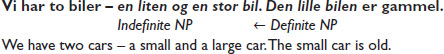

The noun phrase (NP) consists either of a noun or pronoun alone (boken, ‘the book’; hun, ‘she’) as head or an NP with optional determiners (alle hans bøker om grammatikk, ‘all his books about grammar’).

Har du øl ? |

Do you have any beer? |

Katter liker ikke vann. |

Cats do not like water. |

or one preceded by:

An indefinite article |

en katt, a cat |

An adjective attribute |

alkoholfritt øl, non-alcoholic beer |

A measurement attribute |

en liter melk, a litre of milk |

A combination of these |

en kilo god kaffe, a kilo of good coffee |

Dahl var forfatter. |

Dahl was a writer. |

Fant du ølet ? |

Did you find the beer? |

The noun in the definite NP may either occur alone: katten, the cat or it may be preceded by a definite attribute expressing:

totality |

alle tilskuere, all the spectators |

possession |

deres kolleger, their colleagues |

USAs utenriksminister, the US Secretary of State |

|

selection |

første omgang, the first round |

demonstrative |

dette produktet, this product |

determiner |

den katten, that cat; det produktet, that product |

or it may be followed by:

a possessive |

kollegene deres, their colleagues |

a prepositional phrase |

fyren i Washington, the bloke in Washington |

a relative clause |

boka som vi leste, the book we read |

A definite noun phrase may have a complement that agrees with it (see 2.1.1):

kattene er hjemløse |

the cats are homeless |

Generally speaking, only definite noun phrases are duplicated (see 10.7.3.5–6):

Bilen, den har automatgir. |

The car, it has an automatic gear box. |

BUT:

Kaffe, det er godt. |

Coffee, that’s good. |

For clause elements see 10.3ff below. The functions of noun (and pronoun) phrases are:

Den nye bilen er grå. |

The new car is grey. |

Malin kjøpte en terrengsykkel. |

Malin bought a mountainbike. |

Barna gav henne en PC til jul. |

The children gave her a computer for Christmas. |

Han er oversetter. |

He is a translator. |

De kalte kattungene Tom og Jerry. |

They called the kittens Tom and Jerry. |

huset i byen |

the house in town |

A verb phrase consists either of a finite verb (FV, see 10.3.3.1) alone:

Barnet skriker. |

The child is crying. |

or of several verbs, including one finite and one or more non-finite (NFV, see 10.3.3.2) forms:

Barnet hadde skreket hele natten. |

The child had cried all night. |

Alle kunne ha fått det til samme pris. |

|

or a FV (+NFV) and a verb particle, i.e. an adverb or preposition (For compound verbs, see 5.7):

Vi sender over hans brev. |

We are forwarding his letter. |

or a FV (+NFV) and a reflexive pronoun (For reflexive verbs see 5.5.3):

Hun måtte skynde seg. |

She had to rush. |

One view of the verb phrase includes elements governed by the main verb such as objects, complements and adverbials:

Finite verb |

Particle |

Indirect object Subject complement Potential subject |

Direct object Object complement Particle |

Free/Other adverbial |

hengte |

opp |

et maleri |

i hallen |

|

satte |

av |

mjølkespannet |

i vegkrysset |

|

så |

trett |

ut |

hele kvelden |

|

utnevner |

nok |

Inger |

til leder |

neste år |

hørte |

sønnen |

komme opp |

om morgenen |

|

kjørte |

forbi |

bussen |

i høy fart |

Translations: hung up a picture in the dining-room; set down the milk pail at the crossroads; looked tired all evening; will probably appoint Inger leader next year; heard the son get up in the morning; overtook the bus at high speed

The adjective phrase often consists of an adjective or participle (functioning as an adjective) as Head (H) either alone or with adverbial modifiers, primarily adverbs:

temmelig nervøs |

rather nervous |

H |

|

ti meter høy |

ten metres tall |

H |

|

forferdelig urettferdig |

terribly unjust |

H |

Adjective phrases function as:

De var glade. |

They were happy. |

subject comp. |

Det gjorde henne søvnig. |

It made her sleepy. |

object comp. |

en ikke spesielt vellykket forfatter

a not particularly successful writer

det i enhver henseende perfekte hotellet

the in every respect perfect hotel

– in an adjective phrase:

en ekstremt mislykketforfatter |

an extremely unsuccessful author |

– in a clause:

Han hopper fint. |

He jumps well |

The adverb phrase may consist of an adverb (H) either alone or with adverbial modifiers. These modifiers are preposed.

ganske fort |

rather quickly |

H |

|

nesten aldri |

almost never |

H |

Temporal and spatial adverbs can form postposed attributes:

på vei ut |

on the way out |

konkurransen her hjemme |

the competition here at home |

Prepositional phrases used adverbially as modifiers may be postposed:

ute på landet |

out in the country |

ut fra sitt kontor |

out of his office |

The adverb phrase functions mainly as:

Other adverbial (see 10.3.6.1):

Der bor Ivar. |

(Lit. There lives Ivar.) That is where Ivar lives. |

Hun virket veldig fornøyd.

She seemed very pleased.

Han kjørte veldig fort.

He drove very fast.

Prepositional phrases comprise a preposition plus – often – a prepositional complement (7.1.3.1) which is governed by the preposition and may consist of a noun phrase, infinitive phrase or subclause:

toget mot Lillehammer

the train to Lillehammer

Skuddet gikk forbi den norske målvakten.

The shot went past the Norwegian goalkeeper.

Uten tvil er hopp vinterens beste norske gren.

Ski jumping is without doubt Norway’s best sport this winter.

See 7.1.3.4.

I år ble han utnevnt til transportminister.

This year he was appointed Minister of Transport.

The different clause elements (or ‘building blocks’) are each examined in the paragraphs that follow, whilst in 10.4 these are plotted in a scheme showing their relative order in the clause.

In the Norwegian clause, the subject is compulsory except in imperative clauses (Hjelp!, ‘Help!’) and certain relative clauses where it may be omitted. Its form may vary.

The subject usually consists of:

Sofia er min søster. |

Sofia is my sister. |

Drosjen stanset utenfor. |

The taxi stopped outside. |

De kom ut av butikken. |

They left the shop. |

Om de liker meg, er tvilsomt. |

Whether they like me is doubtful. |

Note – An infinitive phrase can also form the subject, see 5.3.1.6.

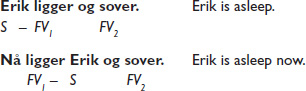

The subject (S) is normally placed next to the finite verb (FV) in main clauses, and its position relative to the finite verb helps to indicate sentence type:

Jan spiste eplet. |

S – FV = Statement |

Jan ate the apple. |

Spiste Jan eplet? |

FV – S = Yes/no question |

Did Jan eat the apple? |

But notice that, when a non-subject (X) begins the clause, Norwegian usually has inverted statements, unlike English:

Hver dag spiser Jan et eple. |

Every day Jan eats an apple. |

X FV S |

In some imperative clauses, an implicit or explicit second person subject comes after the verb:

Gå (du) først! |

(You) go first! |

A formal subject is typically the pronoun det, ‘it’ that does not refer back to a word in the preceding text. We differentiate between four types in 10.3.2.1ff.

In some sentences, det (= ‘it’) as subject has little real meaning and by means of its position is used to indicate sentence type, i.e. statement or question. It is sometimes called a ‘place-holder subject’:

Det regner/snør/hagler. |

It is raining/snowing/hailing. |

Det blir mørkt snart. |

It will be dark soon. |

Det ringte i telefonen. |

The phone rang. |

Er det ikke for varmt herinne? |

Isn’t it too hot in here? |

This is particularly the case with verbs indicating meteorological phenomena (regne), but also applies to sensory verbs that could alternatively take a personal subject (ringe).

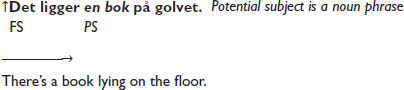

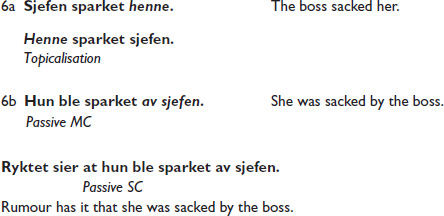

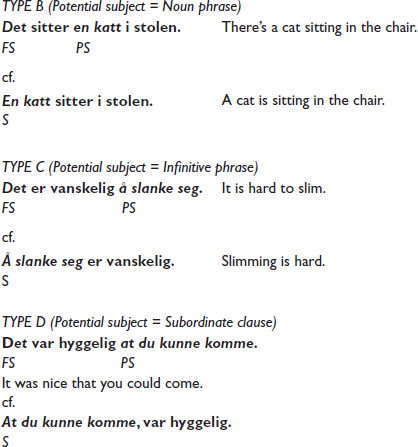

When the subject is postponed (moved to the right in the sentence), an anticipatory det (= ‘there’) is inserted, which is known as the formal subject (FS, Nw. formelt subjekt). The postponed subject is then known as the potential subject (PS, Nw. potensielt subjekt). Type B is used to anticipate an indefinite noun phrase, i.e. a new idea, which rarely comes at the front of the sentence:

Compare the following alternative, which is less likely, particularly in the spoken language:

This construction with det is called an existential sentence (10.7.3.4, Nw. presenteringssetning), because in English it is found only with forms of the verb ‘to be’. In Norwegian, its use is more frequent, and it may be found, as above, with other intransitive verbs.

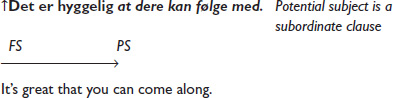

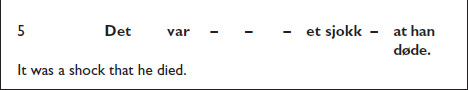

In Type C, the formal subject det (= ‘it’) anticipates an infinitive phrase or subordinate clause as potential subject:

Alternatively, the infinitive phrase or the subclause may come at the front of the sentence:

Type D is in English called the cleft sentence (Nw. utbrytning). Here the construction Det er/var X som…, ‘It was X that/who… ’ places emphasis on a particular element, and the remainder of the original clause is relegated to a subordinate clause (relative clause). The original sentence is, therefore, cleft in two:

Theoretically, almost any clause element may be emphasized in this way:

The finite verb shows tense, voice or mood (cf. 5.1.1f), and its forms include:

(a) Present tense: |

kjører |

Politiet kjører fort. |

The police drive fast. |

||

(b) Past tense: |

kjørte |

De kjørte fort. |

They drove fast. |

||

(c) Imperative: |

kjør |

Kjør! |

Drive! |

||

(d) Present (and, rarely, past) passive: |

kjøres (kjørtes) |

Bilen kjøres av Erik. |

The car is (was) being |

||

driven by Erik. |

||

(e) Subjunctive (rare): |

leve! |

Leve kongen! |

Long live the King! |

Note 1 – When there are several coordinated finite verbs, the subject is as a rule placed either immediately before or after the first verb:

Note 2 – If there are both finite and non-finite verbs in a clause, the finite verb is usually an auxiliary and comes first:

See also 5.2.1.1(e) – (h).

Non-finite forms include:

(a) Infinitive – without å: |

kjøre |

Han skal kjøre. |

– with å: |

å kjøre |

Hun liker å kjøre. |

(b) Past participle (supine): |

kjørt |

Han har kjørt hit. |

(c) Infinitive passive: |

kjøres |

Bilen må kjøres. |

Note 1 – Several infinitives may occur together:

Note 2 – After a modal auxiliary both an infinitive and supine may be found:

De burde ha tenkt på det. |

They should have thought of that. |

Note 3 – The present participle in Norwegian is most often regarded as an adjective or adjectival noun, seldom as a non-finite verb form (5.2.1.1 (g), 5.3.13.)

De spiste lunsj. |

They ate lunch. |

Jeg møtte ham. |

I met him. |

Koret begynte å synge. |

The choir began to sing. |

«Helvete, » ropte hun. |

“Hell,” she cried. |

Jeg vet at han er korrupt. |

I know he’s corrupt. |

Hermine gav Harry en dult. |

Hermione gave Harry a nudge. |

Harry gav blomster til Gulla. |

Harry gave flowers to Ginny. |

De har bygget huset selv. |

They have built the house themselves. |

When stressed, the object usually comes directly after the non-finite verb or verb particle:

Jeg har brent (opp) brevene. |

I’ve burnt the letters. |

(If there is only a finite verb, the object comes after that.)

The object may, however, begin the clause:

Brevene har jeg brent. |

Lit. The letters I’ve burnt. I’ve burnt the letters. |

Object clauses usually come at the end of the clause:

Karl spurte hvem som hadde brent brevene.

Karl asked who had burned the letters.

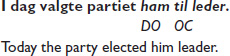

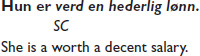

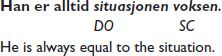

The predicative complement (Nw. predikativ) is found with a copular verb (Nw. kopulaverb), one that has little real content and which either describes a state, e.g. være, ‘be’; hete, ‘be called’; se … ut, ‘look’; virke, ‘seem’, or which results in a change: bli, ‘become’; nominere … til, ‘nominate’. It occupies the same position as the object.

Complements may be:

(a) A noun phrase: |

Bilen er et vrak. |

(b) An adjective phrase: |

Hun er intelligent. |

(c) A subordinate clause: |

Dette er hva det handler om. |

(d) A prepositional phrase: |

De valgte henne til leder. |

(e) An infinitive construction: |

Poenget er å leve livet. |

Predicative complements are of three kinds.

Hun er professor. |

She is a professor. |

Vann blir altfor dyrt. |

Water is becoming too expensive. |

Dette gjorde ham rasende. |

This made him furious. |

Paret kalte gutten Shirley. |

The couple called the lad Shirley. |

Trett og sliten kom hun sent hjem.

Exhausted she came home late.

Som ung var Martin utadvendt.

As a young man, Martin was extrovert.

See also 6.2.1.3, 10.2.5.2.

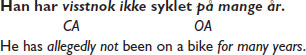

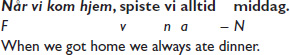

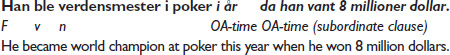

Adverbials are of two types: Clausal adverbials (CA) and Other adverbials (OA):

Han sykler aldri/ofte/sjelden til arbeidet.

He never/often/rarely cycles to work.

Fordi Gene var så pen, undervurderte folk henne.

Because Gene was so beautiful, people underestimated her.

why?

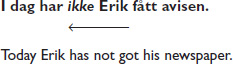

The main types of clausal adverbial are:

(a) Modal adverbs: |

Det er dessverre for sent. |

(b) Conjunctional adverbs: |

Du kommer altså på søndag. |

(c) Prepositional phrases: |

Det er tross alt januar. |

(d) Negations: |

Jeg gambler ikke. |

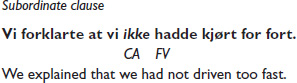

Note – One may also sometimes find the same word order in a subordinate clause as in a main clause (Vi forklarte at vi hadde ikke kjørt for fort, see 10.8.5), but this is less common in writing, and it has a special nuance of meaning.

Vi hadde ikke kjørt for fort denne gangen.

We had not driven too fast this time.

Denne gangen hadde vi ikke kjørt for fort.

This time we had not driven too fast.

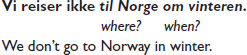

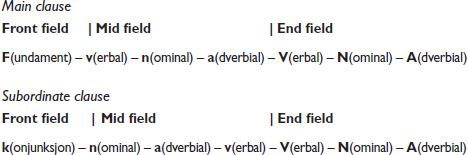

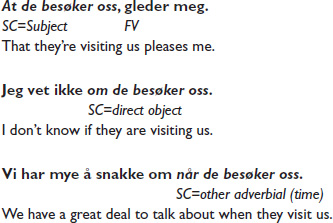

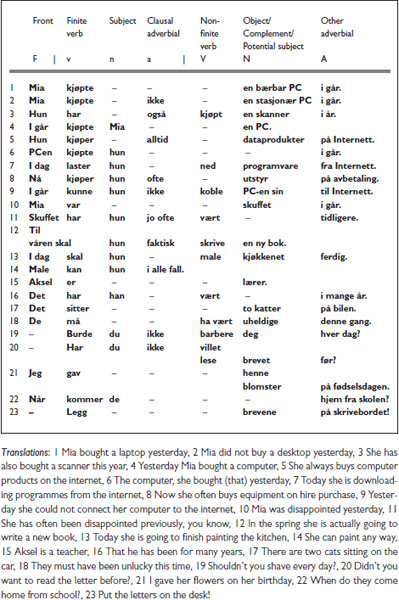

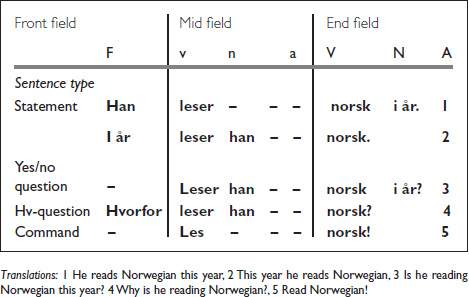

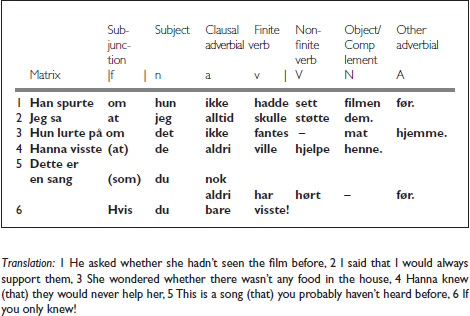

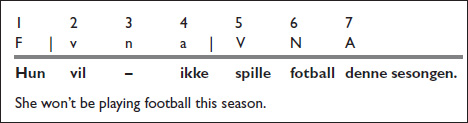

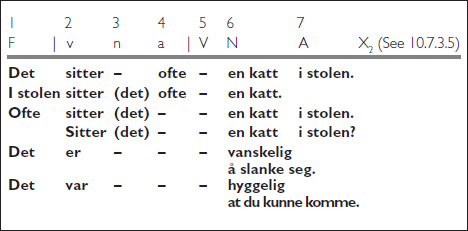

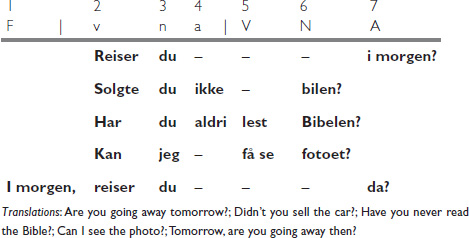

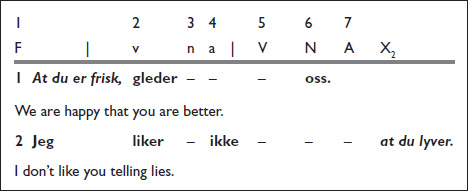

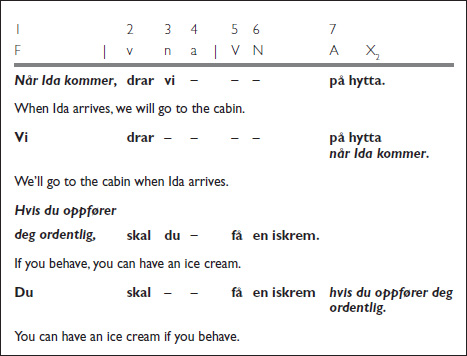

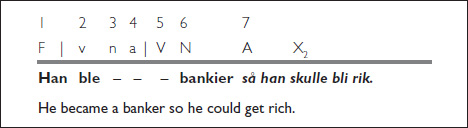

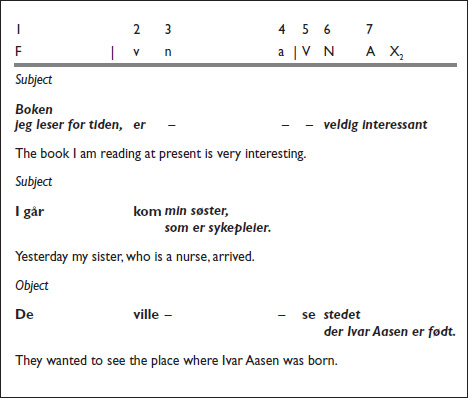

The account of Norwegian word order in this book is based largely on a positional scheme originally developed by Paul Diderichsen for Danish, a syntactically similar language, though there are some minor differences. Diderichsen’s scheme has the great advantage of mapping the entire clause (in principle the sentence), thus indicating the relative positions of all the clause elements simultaneously. Diderichsen uses the following nomenclature for the seven positions in the clause and the three fields:

In what follows, ‘k’ has been replaced by ‘f’ (Norwegian forbinderfelt) in the subordinate clause, to accord with Norwegian practice. In the diagram below, the positions are shown for comparison with the terminology used above in 10.1–10.3. But see 10.6.3 for major exceptions regarding clausal adverbials.

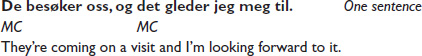

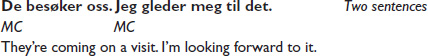

A clause is part of a sentence that usually has a subject and finite verb (with the exception of most imperative constructions (5.4.4, 10.3.1, 10.3.3.1). A sentence comprises either a main clause alone or several coordinated main clauses, and may have one or more subordinate clauses.

(Tenk) at jeg kunne ta så feil ! |

That I could be so wrong! |

When there are several subordinate clauses, one may form part of another, forming a hierarchy (see 9.1.3):

There are two major differences.

While the main clause begins with any clause element in the ‘F’ position, the subordinate clause almost always begins with the subjunction (position ‘f’) and subject (‘n’). Occasionally, however, (see 10.4.3.1) the subordinators at and som are omitted in the subordinate clause. So, while main clause order may be either S – FV (‘straight’) or FV – S (‘inverted’), subordinate clause order is usually S – FV (straight).

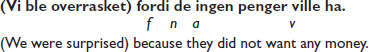

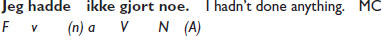

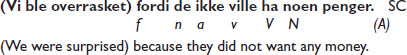

In the main clause, the clausal adverbial (‘a’) comes immediately after the FV (‘v’). In the subordinate clause, the clausal adverbial (a) comes immediately before the finite verb (v), although there are exceptions (see 10.6.3.1).

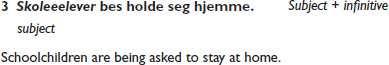

In many sentences, there is more than one element in the ‘a’, ‘V’, ‘N’ and ‘A’ positions. This section discusses the relative order of elements within these positions.

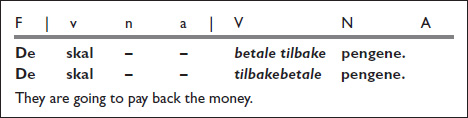

With separable compound verbs, the verb particle occupies the ‘V’ position. When the separable verb is in the non-finite form, both verb and particle occupy this position.

For compound verbs, see 5.7.

Potential |

Subject |

Indirect |

Direct |

Object |

subject |

complement |

object |

object |

complement |

See also 10.3.4.2.

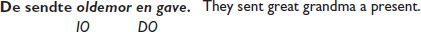

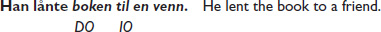

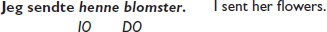

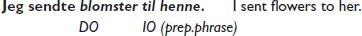

The order of objects is usually the same as in English: the indirect object (IO) precedes the direct object (DO) unless the indirect object is a prepositional phrase:

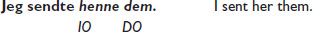

This is also true when the objects are pronouns (see also 10.3.4.2):

BUT:

When the DO is a subordinate clause, it is usually preceded by the IO, as in English:

Note – There are exceptions in some set phrases:

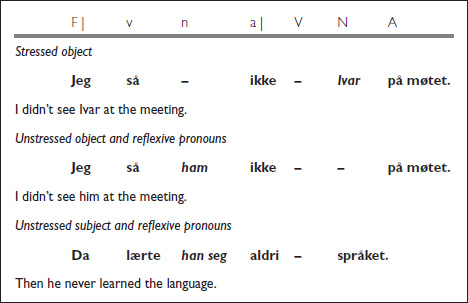

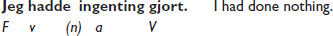

Unlike stressed objects, which go in the ‘N’ position, unstressed object pronouns (including reflexive pronouns) go in the ‘n’ position:

Note – An exception is the clause with a complex verb (i.e. both finite and non-finite verbs):

Han har aldri lært seg språket. |

He has never learnt the language. |

Clauses with an unstressed subject have the order seen in 10.4.2f., namely:

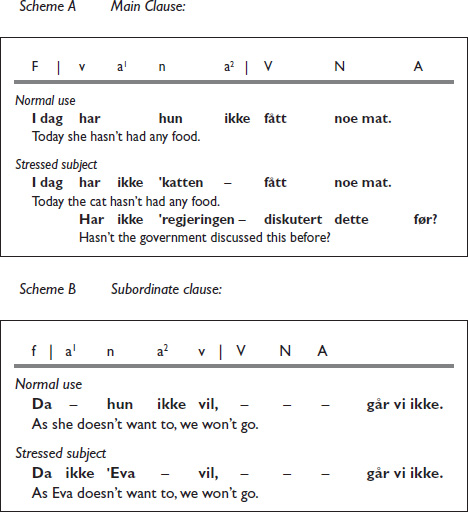

Scheme A |

Main Clause: |

F | –v–n–a – | V–N–A |

Scheme B |

Subordinate clause: |

f | –n–a–v – | V–N–A |

In these clauses, the clausal adverbial adopts the position marked in the table below as a2. Note, therefore, that in normal (unmarked) use in Scheme A, the clausal adverbial frequently comes after the finite verb and in Scheme B, it frequently comes before the finite verb, i.e. in a1.

But, with a stressed subject (marked ' below), the adverbial may come either before or after the finite verb, and some versions of the schemes in Norwegian grammar books consequently have the order where the clausal adverbial goes in a1:

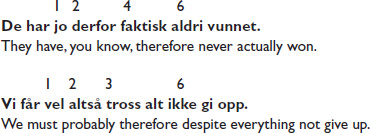

The order of clausal adverbials is usually:

1 Modal, 2 Context, 3 Empathy, 4 Epistemic, 5 Focus, 6 Negation

If several of these are used in the same clause, the order may be as above:

See also 10.6.3.3.

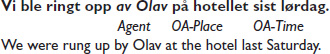

The passive agent usually comes immediately before the Other adverbial expressions in position ‘A’.

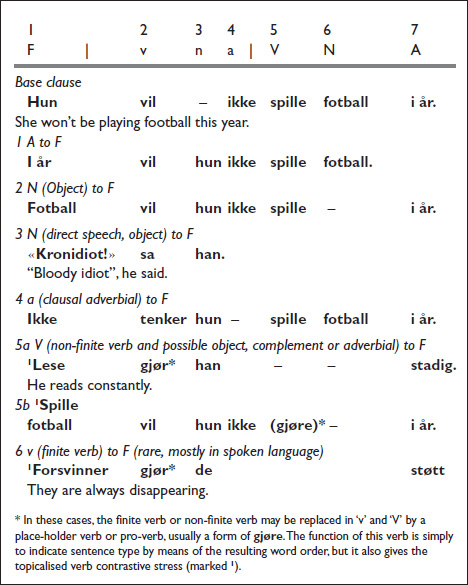

Optional movements within the Norwegian main clause are often made for stylistic reasons.

In order to discuss movements within the clause, we will assume a Norwegian base clause, that is one that is stylistically unmarked, for example:

This base clause begins with the subject and therefore has straight (subject – finite verb) word order, with all the other positions filled except for ‘n’. The subject is, therefore, the theme of the sentence, see 10.9.1.1.

Variations on this order are explored in the paragraphs that follow, where other sentence elements may become the theme. In 10.7.3.3–10.7.3.5 these changes involve a radical redisposition of elements.

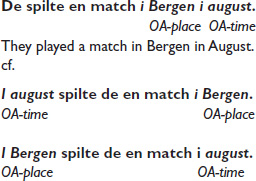

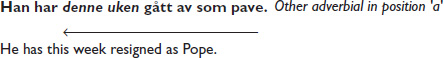

In topicalisation (or fronting, Nw. framflytting, topikalisering)), one of the clause elements usually located in positions 2 to 7 is placed in this first, ‘F’, position, and the subject in the ‘n’ position. The most common topicalisation is of adverbial expressions of time or place.

See also 10.9.1.1f for theme and focus. Numbers below refer to examples in 10.7.2.1 above.

For example, see 1 in 10.7.2.1 above: I år vil hun ikke spille fotball.

Adverbial ‘A’ – the element topicalised provides background information (often establishing time or place, see 10.7.2.4) to the new information that is to come in the clause. It is not emphasised.

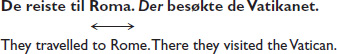

The adverbial (The word der in the second sentence) may serve to link the clause with a previous clause.

For examples see 2 in 10.7.2.1 above: Fotball vil hun ikke spille i år (, men tennis vil hun spille) and also 3–6. The elements topicalised are given added emphasis. The weight of the additional emphasis corresponds to the relative infrequency with which that element appears in ‘F’. In cases 4–6 these topicalisations are not found in English. See also Emphatic topic 10.9.3.2.

Note that (with the exception of example 5b in 10.7.2.1) only one clause element usually occupies the ‘F’ position (10.4.2.1 (a). For instance, only one adverbial is normally topicalised, which is different from English:

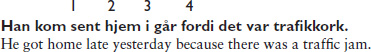

A subordinate clause otherwise found in the ‘A’ position may commonly be found in the ‘F’ position, where it provides background information, as in this temporal clause:

An unstressed element referring to a familiar idea (i.e. a short element) tends to be located to the left of the sentence, while a stressed element introducing a new idea (i.e. a longer element) tends to be located to the right. So, the natural balance of the sentence in spoken and informal written Norwegian is one of ‘end weight’ as in this example:

The implications of the weight principle (Nw. vektprinsippet) are that:

Compare:

At han skal bruke tid på å skrive upassende tweeter med hysteriske utfall mot kvinnelige journalister, har vakt forundring i vide kretser.

That he should spend time on writing inappropriate tweets with hysterical outbursts against female journalists has caused surprise in many circles.

Long subordinate clause in position 'F'

Various implications of the weight principle are explored in 10.7.3.1–10.7.3.6 below.

See also 10.6.4.

Other adverbials (10.3.6.1) are sometimes classified as either ‘free’ or ‘bound’. Free adverbials are those whose position or content is not determined by a governing verb. They can adopt various positions in the clause. Time adverbials are generally free:

When the free adverbial is located in position ‘a’, as in example 3, this is usually an indication of formal written style.

Bound adverbials form a complement to the verb and are usually found in position ‘A’. Place adverbials are bound more often than time adverbials:

For adverbial subordinate clauses see 10.7.2.4, 10.8.2.2, 10.10.2.1.

This also occurs in subordinate clauses:

This order is, however, stylistically marked, and usually it indicates an old-fashioned or literary style.

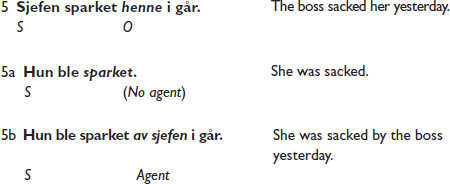

Active |

Passive |

|

1 Noen stjeler biler. |

→ |

Biler stjeles. |

Someone steals cars. |

Cars are stolen. |

|

2 De valgte ham. |

→ |

Han ble valgt. |

They elected him. |

He was elected. |

|

3 Man har invitert oss. |

→ |

Vi har blitt invitert. |

They have invited us. |

We have been invited. |

|

4 Henrik slo ham. |

→ |

Han ble slått av Henrik. |

Henrik hit him. |

He was hit by Henrik. |

In examples 1–3 an expression containing an unimportant subject becomes an agentless passive expression with emphasis on the verb. In example 4 the subject in the base is important, and for emphasis, it is moved rightwards according to the weight principle. See 10.7.3.

See 10.3.2.1f. for types.

In English, this construction is largely only found with the verb ‘to be’, hence the term ‘existential sentence’, but in Norwegian its use extends beyond verbs of existence or non-existence to what might be called ‘presentative’ verbs, i.e. any intransitive verb (cf. the Norwegian term presenteringskonstruksjon).

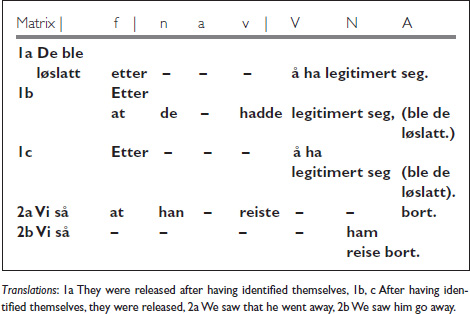

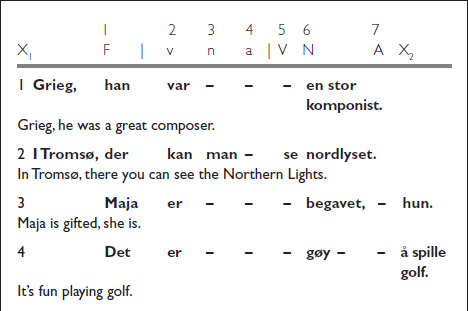

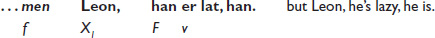

Extra positions (X1, X2) are occasionally added at the beginning and end of the schema to accommodate clauses as potential subject, object clauses or free elements outside the clause.

A position ‘f’ – which one might call a ‘conjunction field’ (Nw. forbinderfelt) – is added before position ‘F’ in the main clause in order to accommodate conjunctions:

This section deals with direct questions. For indirect questions, see 10.8.1.2. There are several different constructions.

These questions are so called because they anticipate either affirmation or denial (see also 10.4.2.3). They have inversion of the finite verb and subject, and the ‘F’ position is usually empty.

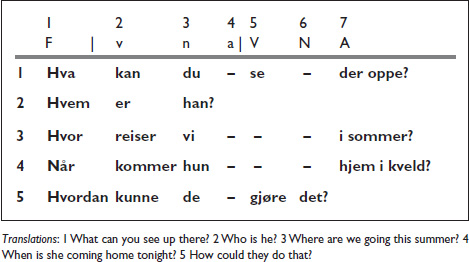

The topic in this kind of question is an interrogative adverb or pronoun, most of which begin with hv– : hvem, ‘who’; hva, ‘what’; hvor, ‘where’; hvilken, ‘which’, etc. (see 4.8) (but notice når, ‘when’) located in the ‘F’ position.

The hv-question requests information about a specific clause element: in example 1 an object, 2 a subject complement, 3 an adverbial of place, 4 an adverbial of time, 5 an adverbial of manner.

Some questions are found in statement form (‘declarative’ questions), when question intonation is used or a tag or tag clause is added:

Du reiser altså i morgen? |

You are leaving tomorrow, then? |

Du reiser ofte, gjør du ikke? |

You travel often, don’t you? |

Det er ikke dårlig, hva? |

That’s not bad, eh? |

Du kommer fra USA, ikke sant? |

You come from the USA, don’t you? |

Du reiser mye, eller? |

You travel a lot, don’t you? |

The last variant with eller as a tag is colloquial and mainly found in speech.

These clauses are introduced by a subordinator such as at, ‘that’; ettersom, ‘as’; fordi, ‘because’; hvis, ‘if, whether’; når, ‘when’; om, ‘if’, etc (see 9.3.1):

See also 10.7.4 for direct questions.

These clauses are introduced by:

Han visste ikke hva han skulle tro.

He didn’t know what he was supposed to believe.

When the hv-word is the subject of the subordinate clause, the subject marker som must be added (cf. 10.8.4.2):

Han ville vite hva som skjedde.

He wanted to know what was happening.

Jeg vet ikke om (hvorvidt) vi kan fortsette.

I don’t know whether we can go on.

These clauses usually occur as a postposed attribute to or are in apposition to a noun phrase, and are introduced by a subjunction or a relative adverb:

Subordinate clauses can be classified according to their function, that is according to the clause element they represent in the larger sentence.

See also 10.3.1, 10.3.4.

At du vegret, var meget klokt. |

Subject |

That you refused was very sensible. |

|

Jeg håper at han vinner. |

Object |

I am hoping that he will win. |

Det er uvisst hvem som blir sjef. |

Potential subject |

It is not known who will be the boss. |

|

Vi spurte henne hva hun hadde tenkt å gjøre. |

Object |

We asked her what she was considering doing. |

These include:

There are two types: restrictive and non-restrictive:

De bileierne som allerede har betalt årsavgift, må ikke betale mer.

Those car-owners who have already paid road tax do not have to pay anything more.

Bileierne, som for øvrig allerede betaler en årsavgift, må betale denne avgiften.

The car-owners, who incidentally already pay road tax, have to pay this charge.

When the relative clause relates to the subject, som is necessary, but in other cases it is often omitted (see 9.1.5.3f, 9.4.1.1(b), 10.8.4.2):

Compare:

See also: 10.3.1.2, 10.3.4.1(a), 10.3.5.1(c), 10.4.1.2f., 10.7.2.4, 10.7.3.4).

These usually occupy the ‘F’ or ‘X2’ position.

Note – It is also possible in formal written language to locate the adverbial clause in ‘a’. See 10.7.3.1.

Some adverbial clauses (consecutive) usually only occupy the ‘A’ position:

Attributive clauses that are associated with the subject or object occupy the same position as these, i.e. ‘F’, ‘n’ or ‘N’:

As in English, at, ‘that’ is often omitted after verbs of saying, thinking or perceiving:

De sa (at) de skulle komme neste uke. |

They said they were coming next week. |

Han synes (at) det er hyggelig. |

He thinks it’s nice. |

Filmen (som) vi så, var kjedelig. |

Object |

The film we saw was boring. |

|

Vi fant den skjorta (som) han lette etter. |

Object |

We found the shirt he was looking for. |

Hun skriver krim, noe (som) publikum liker.

She writes detective stories, something the public like.

Subordinate clauses usually have no topic and possess subject-verb order. The order is usually subject – clausal adverbial – finite verb:

De sa at de ikke kunne komme. |

They said they couldn’t come. |

But some subordinate clauses follow Scheme A (10.4.2). These are detailed in 10.8.5.1f below.

Main clause word order is found in some at-clauses after a verb of saying:

De sa at når de kom hjem, skulle de spise middag.

They said that when they got home they would eat dinner.

De sa at de kunne ikke komme. cf. 10.8.5. |

(cf. ‘Vi kan ikke komme.’) |

See also conditional subjunctions, 9.3.4.3.

Conditional clauses usually begin with a subordinator:

cf. Vi kan bygge et svømmebasseng hvis pengene strekker til.

This kind of conditional clause, which has no subordinator, but instead inverted word order and an unfilled ‘F’ position, usually comes at the beginning of the sentence. This type of conditional is much more frequent in Norwegian:

Hadde jeg nok penger, skulle jeg bygge et svømmebasseng.

If I had enough money, I would build a swimming pool.

Leser du bruksanvisningen nøye, vil det være lettere å sette det sammen.

If you read the instructions carefully, it will be easier to assemble it.

This construction exists in English elevated and formal style after ‘had’, ‘were’, ‘should’:

Cf.

Hvis jeg hadde nok penger, …

Hvis du leser bruksanvisningen nøye, …

Most main clauses follow Scheme A (10.4.2), but a few main clause sentences have Scheme B word order (10.4.3). These include three cases detailed below in 10.8.7.1ff.

This construction is usually associated with emotional intensity.

Kanskje, ‘perhaps’ and kan hende, ‘may be’ are the remnants of verb phrases historically followed by at: det kan skje at and det kan hende at. Therefore, the sentences below may follow schema B:

(Schema A is, however, also possible.)

These are a type of direct question that repeats part or all of what someone has just asked.

Question: |

«Er du allerede ferdig?» |

“Are you ready already?” |

Echo question: |

«Om jeg allerede er ferdig?» |

“Am I ready already?” |

In Norwegian, three factors determine the order of the words in the clause: the information structure, the syntactic function and the weight.

The information structure of the sentence is such that it is divided into two parts, ‘given’ information and ‘new’ information. The given information is called the theme and the new information the focus (Nw. tema and rema respectively). The first element after any conjunction is the theme, while the rest is focus:

Theme |

Focus |

Jeg |

liker å leve i Frankrike |

I |

like living in France. |

Der |

kan jeg koble av. |

There |

I can relax. |

Det |

er bra for helsen min. |

That |

is good for my health. |

Derfor |

må jeg dra dit hver sommer. |

That’s why |

I have to go there every summer. |

As can be seen from the short text above, the element that forms the theme is governed by the context. The order within the focus is primarily governed by the syntactic function of the clausal elements involved (subject, object, etc.), compare:

I går slo Man U Chelsea. |

Yesterday Man U beat Chelsea. |

I går slo Chelsea Man U. |

Yesterday Chelsea beat Man U. |

Because the focus involves new information or new ideas, it is often longer and ‘heavier’ than the theme, so end-weight is natural in the sentence. See the weight principle, 10.7.3. The end of the sentence also forms a natural stress position, so we can also talk of end-focus.

cf. |

|

Hun kjøpte en ny platetopp. |

She bought a new hob. |

In the spoken language, it is possible to use voice stress to emphasise any element without altering the word order:

Subject |

||

Subject |

'Frida solgte hytta si i fjor sommer. |

(i.e. not Sara or…) |

Verb |

Frida 'solgte hytta si i fjor sommer. |

(i.e. did not give it away) |

Object |

Frida solgte 'hytta si i fjor sommer. |

(i.e. not her flat) |

Adverbial |

Frida solgte hytta si 'i fjor sommer. |

(i.e. not this summer) |

This is, of course, not possible in written Norwegian, and various strategies can be adopted in writing in order to provide an unequivocal marking of elements, such as fronting (10.9.3), raising (10.9.4), duplication (10.9.5) or the cleft sentence (10.3.2.4).

As we have seen above, the front position ‘F’ usually, but not always, contains given information (10.9.1). It is in this context practical to think of topics (elements in ‘F’) as being of two kinds.

Læreren/Eva/Hun kom inn i forelesningssalen.

The teacher/Eva/She came into the lecture room.

This is regarded as an unmarked or base clause (10.7.1).

I neste uke reiser jeg til Tyskland. |

Next week I’m going to Germany. |

I Berlin skal jeg treffe Tobi. |

In Berlin, I’m meeting Tobi. |

Bilen kan ikke godkjennes. Et frontlys er ødelagt.

The car cannot pass its test. One headlight is broken.

It is clear that the headlight belongs to the car.

See also 10.7.2.1ff.

The ‘F’ position is, less frequently, used to add extra emphasis (marked ') to an element already ‘heavy’ in information. Emphatic topics may include the object, a verb phrase, infinitive phrase or negation. This kind of topicalisation is rare in English, but is considerably more frequent in Norwegian.

'Lære noe gjør jeg hver dag. |

I learn something every day. |

'Jage etter jenter gjør han stadig. |

He’s always running after girls. |

'Aldri har jeg sett maken. |

I have never seen the like. |

Raising (often resulting in what Norwegians call setningsknute) is the term used when an element in a subordinate clause is fronted in the matrix, thus ‘raising’ it to a higher level:

Jeg synes ikke |

(at) den filmen var så vellykket. |

Matrix |

subject in the subordinate clause |

I don’t think |

that film was so successful. |

cf. |

|

Den filmen synes jeg ikke var så vellykket. |

|

Topic in the main clause |

|

That film I don’t think was so successful. |

|

Frequent kinds of raising are:

Vi hadde en katt som het Smilla. |

We had a cat called Smilla. |

cf. |

|

Smilla hadde vi en katt som het. |

|

(raised subject complement in subclause) |

Jeg vil ikke si at de er dyre. cf. |

I wouldn’t say they are expensive. |

Dyre vil jeg ikke si (at) de er. |

|

(raised subject complement in subclause) |

Jeg tror ikke at Shakespeare skrev det dramaet.

I don’t believe Shakespeare wrote that drama.

cf.

Det dramaet tror jeg ikke (at) Shakespeare skrev.

(raised object in subclause)

Jeg regner med at vi har arbeidet ferdig i neste uke.

I expect we will have the work completed next week.

cf.

Ineste uke regner jeg med at vi har arbeidet ferdig.

(raised adverbial in subclause)

See also extra positions, 10.7.3.5.

The theme in the ‘F’ position can be moved leftwards to the ‘X1’ position and at the same time be represented in ‘F’ by a ‘pro-word’. This is often a personal (subject or object) pronoun or an adverb like så, da or der:

Amundsen, han kom først til polen. Amundsen, he arrived at the pole first. |

Subject duplicated |

Sigrid Undset, henne gav de Nobelprisen i 1928. |

Object duplicated |

Sigrid Undset, they gave her the Nobel Prize in 1928. |

|

Forsiktig med penger, det var han ikke. |

Complement duplicated |

Careful with money he was not. |

|

I Paris, der vil jeg tilbringe påsken. |

Adverbial duplicated |

In Paris, that’s where I want to spend Easter. |

|

I fjor, så/da var vi i Sverige. |

Adverbial duplicated |

Last year, then we were in Sweden. |

Although duplication is more characteristic of the spoken language, it does occur in written texts, especially when the element in ‘X1’ is an adverbial clause:

In the ‘X2’ position one finds elements that are also represented inside the clause. The element in the extra position duplicates the sense of the one inside the clause, usually a pronoun, pro-word or adverb.

Maja er ikke frisk, hun.

Maja is not well (, she [isn’t]).

De arbeidsløse er det synd på, de.

The unemployed are to be pitied (they [are]).

På universitetet var det fint, der.

At the university (there) it was great.

Det var så spennende, så.

It was so exciting(, it was).

A clause usually contains both a subject and a finite verb. But there are some exceptions to this pattern.

See also 5.4.4.

These are usually found with the imperative form of the verb and have an implicit subject in the second person:

Spis (du) smørbrødet ditt nå! |

Eat up your sandwich now! |

Note 1 – The subject is occasionally explicit and then follows the finite verb:

Kjør du! |

You drive! |

Note 2 – The negative can precede or follow the finite verb.

Ikke gjør dette hjemme! |

Don’t do this at home! |

Tro ikke at kjærlighet varer. |

Don’t think that love lasts. |

(H. Wildenvey) |

Han kom fram til oss og (han) skrek. |

Subject deleted |

He came up to us and (he) shouted. |

|

Aksel spiser oksekjøtt og Emma (spiser) fisk. |

Finite verb deleted |

Aksel is eating beef and Emma (is eating) fish. |

Han skal ta seg en kaffepause nå og hun |

Finite verb and object deleted |

(skal ta seg en kaffepause) om en time. |

|

He’ll take a coffee break now and she (’ll take a coffee break) in an hour. |

Her er jenta som vant kampen.

Here is the girl that won the match.

Her er bilen jenta vant.

Here is the car the girl won.

In the example following, a preposition is followed by a finite subordinate clause:

But, in this case the finite verb (and here the subject) may be omitted if the subject is the same in both clauses. Then, an infinitive with å replaces them:

Clauses lacking a finite verb are of several different kinds, see 10.10.2.1ff.

Han var flere ganger alene med keeper uten å score.

He was alone with the goalkeeper several times without scoring.

Vi tar betalt for å bringe varene hjem til folk.

We charge for home delivery.

Det er bedre enn å slenge rundt uten arbeide.

It is better than hanging about without any work.

Det er fortsatt tryggere å fly enn å kjøre bil.

It is still safer to fly than to drive.

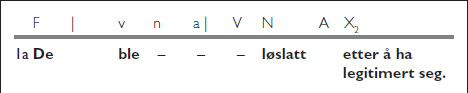

The noun phrase preceding the infinitive has a double function, both as object of the verb in the matrix and as the logical or implied subject of the infinitive:

Jeg så ham falle. |

cf. |

Jeg så at han falt. |

I saw him fall. |

I saw that he fell. |

Other examples:

Jeg bad dem bli til middag. |

I asked them to stay for dinner. |

Hun lot meg snakke videre. |

She allowed me to go on talking. |

Klubben tillater publikum å se på treningene.

The club allows the public to watch the training sessions.

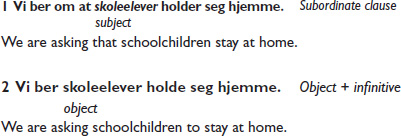

We may regard this as a development of the object + infinitive construction above (in an active sentence) in which the ‘object’ then becomes the subject of a passive verb. Compare the following: