Alongside civil registration and the census, parish material, and more specifically parish registers, forms the third big genealogical source. Together they can prove links between generations (via baptisms) and between branches of the family (via marriages), and in England, Wales and Scotland in particular take your research back well beyond the start of civil registration. Indeed, they can potentially help you trace your line back to the sixteenth century – although this is rare in practice.

Tracking down civil registration records and census material is, in theory at least, relatively straightforward. For parish level sources in particular, the situation is more complicated. But it is worth the effort – there’s nothing quite liking seeing original registers, reading the handwriting and sometimes comments from the clergy who presided over the baptism, marriage or burial of an ancestor, sometimes with the marks and signatures of your ancestors and close family. Also, thanks to widespread transcription and indexing, not least by the LDS Church, and the mass county level digitisations through websites such as Ancestry and Findmypast, it’s becoming easier to track down parish sources remotely. The situation in Scotland is more advanced in that the equivalent registers, known as Old Parish Register, are available via ScotlandsPeople.

Parish-level records are an exciting area for genealogists. In this first section of this chapter we will be looking at material relating to birth, marriage and death. In the next section we will look in more detail at other parish-level sources, sometimes referred to as ‘parish chest’ material, as well as the related BMD sources such as marriage banns and licences and burial records.

As explored in Chapter 1, ‘The State and the Parish’, the way that parish, borough, city, hundred and county administration hangs together can cause confusion. The East Riding of Yorkshire’s archives service, based at the Treasure House in Beverley, looks after parish registers for the East Riding Archdeaconry – but as ecclesiastical boundaries are different to local authority boundaries, the Archdeaconry does not cover the whole of the East Riding. And this situation is not unique – most regions can offer up their own idiosyncrasies.

In built-up, urban areas identifying the correct parish and where that parish material is likely to reside is even more critical. The London Metropolitan Archives, for example, holds some 17,000 parish registers from more than 700 Church of England parishes, covering central and north-west London. But, as the ‘Metropolitan’ archives it covers only certain parts of the city – they have no City of Westminster parish registers at all, and many Greater London parish material resides in smaller borough collections. Thankfully, LMA’s parish material is arranged alphabetically by borough, and much of it is available through an ongoing digitisation partnership with ancestry.co.uk.

Some of the best advice is often the most obvious. It is generally a good idea to look both ways before stepping out into the road, for example. And although this may seem equally obvious, my one piece of advice is to make sure you are certain of the parish in which your ancestor lived – especially if you are visiting an archive in person. Most local and county archives, and many regional family history societies, provide online guides to their parish holdings and coverage. It really is worth the time investment to explore these thoroughly as you get to know an area.

Parish records were originally generated by and preserved at the parish church. In 1538, parish priests were told to start keeping record of all baptisms, marriages and burials during the week. The new records were to be kept in a ‘sure coffer’ with two locks. And it is these boxes, many of which still survive in parish churches, that has lead to the term ‘parish chest material’ being used to describe all kinds of parish sources.

The system took time to bed in. To begin with not everyone took it seriously, fearing the paperwork would lead to further taxes being levied on the Church. Plus many kept the records in a haphazard way, on loose sheets of paper, until further decrees ordered that they kept the records in bound books. So, while there are survivals right back to the late 1530s, 1558 is usually seen as the birth date of the parish register as this was the year of a royal proclamation that records should be kept on parchment, meaning more have survived.

To begin with, single registers contained all events. Essex Record Office looks after some really fine early parish registers. One example from Chelmsford, dating from May 1543, mixes baptisms, marriages and burials together in one sequence, with the writer putting a key in the margin: ‘C’ for christening,‘M’ for marriage and ‘O’ probably for ‘obit’ (Latin for ‘(s)he died’). The page also has occasional use of red ink which is unexplained, although local archivists suspect that it may reflect the social status of the parties. William Mildmay, for example, whose baptism appears in red, was a member of Chelmsford’s most prominent family.

External influences, particularly the Civil War, resulted in gaps and the detail entered varies depending on the incumbent or clerk who kept the registers. Hampshire chaplain William Rawlins noted a great deal of information about his parishioners. In the second entry of the page of baptisms and burials for Winchester St Cross with St Faith parish covering the years 1789 to 1791, he notes that a 52-year-old woman was for ‘several years Cook’ at the almshouse St Cross Hospital, while Robert Page,‘a truly pious and good man’, had been porter there. Overleaf we have the most extraordinary of entries where he describes the burial of Richard Hart, a Brother of St Cross, in a coffin made by himself out of a Spanish man-of-war he bought while working as a carpenter at Portsmouth Dock twenty years before. Further we learn that he kept the coffin in his room, drawn up on pulleys to the ceiling and ‘had painted funeral processions, skulls and other emblems of mortality’ on the side. He goes on: ‘Brother Hart was a man of a very singular turn and disposition.’ He ends the same page from 1791 with an entry for 60-year-old pauper widow Martha Dubber. He adds: ‘Her husband, in 1780, was crushed to death by the fall of earth in a sand pit.’

Another example from Essex is the register for the parish of Stansted Mountfitchet covering the years 1609 to 1610, which again has all the hallmarks of the period – tricky handwriting, marriage entries that simply name two parties involved, baptism entries that name the father but not the mother. However, it also boasts an extraordinarily long-delayed entry. At the top of the right-hand page of baptisms from 1610, a later hand has inserted: ‘John Burnet the old baylif of Stansted Hall was born this year who lived 90 years, or very near, dying Oct. the 27th 1699.’

You’ll sometimes come across pointed digs at parishioners – imagine the character of Mr Collins from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and you’ll get the idea. Also, some vicars took it upon themselves to note down all kinds of details they were not strictly required to record. Travel to Meirionnydd Record Office in Gwynedd, Wales, and you’ll find a burial register that has notes in the side margin describing the sinking of the ship Wapela on the night of 24 January 1868. Many of those lost are noted in the register, including Captain Isaac Lincoln Orr, whose body was later disinterred and sent to North America. And the final entry on the page from the year 1844 records the burial of a young black cabin boy whose body was found washed up on the shore. As the boy’s name was unknown, the burial entry reads simply ‘Bottle of Beer’ – as one was found in his jacket pocket.

Similarly, the Borthwick Institute in York, which looks after the huge York Diocesan Archive, has a Pocklington burial entry from April 1733 that records: ‘Thomas Pelling from Burton Stather in Lincolnshire, a Flying Man who was killed by jumping against the Battlement of the Choir when coming down the Rope from the Steeple.’ ‘Flying men’ were part of a 1730s craze for rope dancing, walking and sliding. (You can find out more via the Institute’s blog at borthwickinstitute.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/isit-bird-is-it-plane-no-its-flying.html.)

New laws formalised and standardised the system over time. One important development for genealogists occurred in 1597, when an Act of Parliament ordered the keeping of what are known as Bishop’s Transcripts. These were contemporary copies of the parish registers, made by local clergy and then sent to the bishop of the diocese. Today they offer the frustrated genealogist a second chance – where you find a gap in the parish records, it may often be the case that the Bishop’s Transcripts come to the rescue. Although remember that the Bishop’s Transcripts sometimes had less detail than the original registers.

It was tradition but not law that marriages should take place in the home parish, but clandestine marriages were commonplace. This was curtailed by Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, passed in 1754. The wonderfully named Nottinghamshire clergyman the Revd W. Sweetapple was notorious for marrying couples from near and far at his Fledborough parish church. Check the Fledborough parish register and the number of marriages appearing in the register drops dramatically after the passing of Hardwicke’s Marriage Act.

The marriage register from Ashen, a rural parish on the Suffolk border, stops short in 1753. This is because Hardwicke’s Marriage Act laid down a single, compulsory form of entry, so that most parishes acquired a new marriage register in 1754. After the Act marriage registers included signatures of brides, grooms and witnesses, and the clear distinction made between marriages by banns and by licence.

Wedding dresses can give clues about when a marriage took place. Once you have found the correct marriage register entry it should include signatures of brides, grooms and witnesses.

Baptism registers had their formats fixed by an Act of 1812, usually called Rose’s Act. For the first time, fathers’ occupations were recorded systematically. There was no requirement to record the child’s date of birth, but clergymen sometimes squeezed the information in.

The same Act also formalised burial registers. Burial entries can be disappointingly brief: they rarely name any of the deceased’s relatives, or give any clue as to where in the churchyard the grave actually lies. ‘Abode’, during this period, is usually simply the name of the parish. Finally, the year 1837 brought the introduction of a pattern of marriage register still essentially in use today. The most useful addition for family historians is probably the fathers’ names and occupations.

There were still regional variations. The Borthwick Institute, which holds parish records for the modern archdeaconry of York – York City parishes and those parishes within approximately a 20-mile radius of the city – is home to the so-called ‘Dade registers’. These were a more rigorous and detailed form of record keeping introduced by York clergyman William Dade to three York parishes in the early 1770s, before being adopted more generally across the diocese. Full Dade baptism registers provide the child’s name and seniority (e.g. fourth child), the father’s name, abode, profession and descent (including the paternal grandparents’ names and abode, the grandfather’s occupation, and details of the paternal great-grandfather), and the mother’s name and descent (including the maternal grandfather’s name, abode and occupation and the maternal grandmother’s name and descent). Dade burial registers are also of particular interest as they include the age and cause of death.

Another example is the ‘Barrington registers’, named after the Lord Bishop of Salisbury, the Rt Revd Shute Barrington. In the diocese of Durham between 1798 and 1812, he ordered that more detailed information should be kept in baptism and burial registers. Between these dates each baptism entry should give the date of baptism, name of the child, date of birth, position in the family, the occupation and abode of the father, and the maiden name and place of origin of the mother. Burial registers give the name and abode of the deceased, his parentage, occupation, the date of death, date of burial and age.

In Scotland parish registers are referred to as Old Parish Registers, or OPRs. These were maintained by parishes of the Established Church – the Church of Scotland – usually by the parish minister or session clerk. The National Records of Scotland holds the surviving original registers and these are accessible via the ScotlandsPeople website.

As with the early system south of the border, to begin with there was no standardised format, so you will find a great deal of variation. The relevant ScotlandsPeople page warns that information may be ‘sparse, unreliable and difficult to read’. The oldest surviving register dates from 1553 (the baptisms and banns from Errol in Perthshire), but while there was a requirement from 1552 that parishes record baptisms and marriages, many did not commence until much later, partly because registration was costly and unpopular. Also, while some Nonconformists can be found in these registers, many chose to have events registered in their own churches.

In Ireland, with so little surviving census material from the nineteenth century, the parish registers take on even more importance. Indeed, for many researchers they offer the only potential source for tracing an individual.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the National Library of Ireland microfilmed registers from the majority of Catholic parishes in Ireland and Northern Ireland. The registers contain records of baptisms and marriages from the majority of Catholic parishes up to 1880. Digital images from these microfilms are now freely available on the website Catholic Parish Registers at the NLI: registers.nli.ie. The start dates of the registers vary from the 1740/1750s in some city parishes in Dublin, Cork, Galway, Waterford and Limerick to the 1780/1790s in counties such as Kildare, Wexford, Waterford and Kilkenny. Registers for parishes along the western seaboard do not generally begin until the 1850/1860s.

The National Library of Ireland website (registers.nli.ie) where you can search digitised Catholic parish registers from the majority of Catholic parishes in Ireland and Northern Ireland up to 1880.

Catholic christenings generally took place as soon as possible after children were born, sometimes on the same day. The records include the date of baptism, names of child, father and mother (with maiden surname in later records), and the sponsors or godparents. Some christening records also include the child’s birth date and the family’s place of residence.

Marriage records normally provide the date of the marriage, the names of the bride and groom, and the names of the witnesses. Occasionally, places of residence are listed. Meanwhile, burials would record the name of the deceased, date of burial and sometimes an occupation or residence (townland). Later years often include the age at death and for children at least one of the names of the parents, usually the father.

There are also Church of Ireland (Anglican Church) parochial records, which often remain with the relevant parishes. It is estimated that they survive for about one-third of the parishes throughout the country. Many registers (originals, copies and microfilmed examples) are held in the National Archives of Ireland. PRONI also holds copies of surviving Church of Ireland registers for the dioceses of Armagh, Clogher, Connor, Derry, Dromore, Down, Kilmore and Raphoe.

Registers were originally kept by the church, but most have since now been deposited in diocesan archives or county record offices, often accessible as microform copies in archives and local libraries.

Genealogists and academic societies have been transcribing and indexing parish registers since Victorian times, and many groups and societies produced printed transcripts and indexes – such as the Parish Register Society, the Harleian Society, Phillimore & Co. and the Society of Genealogists.

Regional genealogical groups have also produced transcriptions, indexes and other finding aids. Indeed, one important national project, overseen by the Federation of Family History Societies, was the National Burial Index (NBI). This groundbreaking project led to the first published edition of the NBI in 2001, containing some 5.4 million records, derived mainly from registers and Bishop’s Transcripts. The NBI has since gone through several editions and is now available online via Findmypast (the majority of the records cover the period from 1813 to 1850).

Lots of microform copies of parish material are available through Family History Centres run by the LDS Church, which also preserves the mind-boggling collections at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. The LDS Church also produced the International Genealogical Index (the IGI), which includes indexed data mainly from baptisms and marriages. This is available online but, as with all transcriptions, should always be used with caution, as errors can occur in legibility of the original document or the microfilm copy.

In more recent years FamilySearch has continued partnerships with regional archives and commercial partners to further digitise parish-level material. Durham University Palace Green Library, for example, looks after Bishop’s Transcripts of County Durham and Northumberland parish registers from between 1760 and 1840. Images of these transcripts are all available through FamilySearch. (You can find out more about this and other family history sources via the Library’s dedicated genealogical portal familyrecords.dur.ac.uk.)

There’s lot of material online, but also lots of regional variation. In Yorkshire, for example, the situation is changing rapidly as millions of baptism, marriage and burial register entries are coming to findmypast.co.uk through agreements with six Yorkshire archives. At the time of writing, around 2,700 parish registers from over 250 parishes in the dioceses of York, Bradford and Ripon and Leeds were being digitised. Meanwhile, the site already boasts the Staffordshire Collection, which, when complete, will comprise around 6 million searchable transcripts/images covering all Anglican parish registers up to 1900, and including Stoke-on-Trent and parishes now within the City of Wolverhampton, as well as the Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell and Walsall. Meanwhile, volunteers are busy creating and adding to indexes on the dedicated Staffordshire Name Indexes site (www.staffsnameindexes.org.uk). You should also look out for ‘online parish clerks’ projects, which often transcribe and provide parish-level data free of charge. Cornwall Online Parish Clerks, for example, can be found at cornwall-opc.org.

Some more useful websites with parish register transcriptions and finding aids are listed below.

● Parish registers often survive back to the mid-sixteenth century. The earliest register entries were often little more than lists of names. Parish registers were gradually standardised through Acts of 1753 and 1812.

● Nonconformist and other non-parochial births and baptisms, deaths and burials (and some marriages) can be searched via www.BMDregisters.co.uk.

● Most Nonconformists were required by law to marry in Church of England churches between 1754 and 1837. So you may well find records of them in Anglican parish registers.

● TNA holds Clandestine Marriages & Baptisms in the Fleet Prison, King’s Bench Prison, the Mint & the May Fair Chapel ranging from 1667 to c. 1777.

● There are alternative sources of BMD data – The Gentleman’s Magazine, for example, founded in 1731 and running for almost 200 years, would often include lists of births, marriages, deaths, bankruptcies and military promotions.

ScotlandsPeople: scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Offers access to Old Parish Registers and Catholic Registers from across Scotland.

FamilySearch: familysearch.org

Hosts the International Genealogical Index (IGI), a mass parish-level source first published as a computer file in 1973. There are also vast indexes, transcriptions and register images for other parts of the UK.

FreeREG: freereg.org.uk

Volunteer led drive to provide free online searches of transcribed parish and Nonconformist registers.

National Library of Wales: llgc.org.uk

Has parish registers from over 500 parishes on microfilm in the South Reading Room. It also has archives of the Church in Wales (excluding original parish registers but including Bishop’s Transcripts). Findmypast has a significant Wales Collection of parish material.

National Library of Ireland: nli.ie

The NLI has made its collection of Catholic parish register microfilms freely available via registers.nli.ie.

National Records of Scotland: nationalrecordsofscotland.gov.uk

PRONI: proni.gov.uk

Ancestry: ancestry.co.uk/parish

Essex Ancestors: seax.essexcc.gov.uk/EssexAncestors.aspx

The Essex Record Office digital gateway to various sources including parish registers.

Findmypast: findmypast.co.uk

The Genealogist: thegenealogist.co.uk/parish_records/

Datasets include the noted Phillimore transcripts of marriages, as well as it has various regional collections – it recently announced a new agreement to digitise Norfolk parish/historical records.

Parish Chest: parishchest.com

Lincs to the Past: www.lincstothepast.com/help/parish-registers/

Access Lincolnshire parish registers.

Federation of Family History Societies: ffhs.org.uk

London Registers: www.parishregister.com

Specialises in parish data covering London, particularly from the Docklands.

UK BMD: ukbmd.org.uk

Useful lists of online parish data including Online Parish Clerk websites such as Dorset Online Parish Clerks (opcdorset.org), Cornwall (www.cornwall-opc-database.org) and Kent (kent-opc.org).

Sheffield Indexers: sheffieldindexers.com/ParishBaptismIndex.html

Cumberland & Westmorland Parish Registers: cumberlandarchives.co.uk

‘Parish chest records’ refer to parish-level records that were traditionally stored in a parish chest or strong box. These include the likes of vestry minutes, churchwardens’ accounts and Poor Law material. Some parish chest records, such as bastardy bonds and records of Overseers of the Poor are explored in more detail in Chapter 4, ‘Secrets, Scandals and Hard Times’, while apprenticeship records appear in Chapter 4, ‘Working Lives’. Here we’re going to explore not only these parish-level records, but also some of the alternative sources relating to marriages and deaths.

Fontmell Magna church, where my parents were married, my grandfather was churchwarden and I was mistaken for a girl.

Many genealogists ignore other parish chest material as they are not nearly so likely to have been indexed or transcribed, so accessing and exploring them is time consuming. But they can provide you with a vivid picture of the workings of the local community, about the life of a parish.

The earliest surviving parish records are often the accounts of churchwardens. Their chief responsibility was the maintenance of the church building and its contents. That may sound unpromising from a genealogical perspective, but sometimes they offer more than you might expect. A page of accounts for Great Dunmow in 1538, held at Essex Record Office, includes a list of rents and other receipts, headed by 41 shillings gathered at Christmas by the Lord of Misrule, William Stuard. There’s also a list of subscribers towards ‘the greate bell clapper’ – most men contributed a penny or less, although three widows were also named on the list.

Churchwardens were also responsible to the bishop or magistrate for presenting any wrongdoings at quarter sessions, including failure to attend church, drunkenness or other undesirable behaviour. You can explore the kinds of cases that might reach the Diocesan Courts via the wonderful Cause Papers Database at www.hrionline.ac.uk/causepapers/. These are from the Archbishopric of York and span the years 1300 to 1858; the originals are held in the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York. A simple search by the word ‘churchwarden’ resulted in a case from October 1556, when Robert Fox, the vicar’s clerk at St Martin le Grande, Coney Street, York, was accused of drunkenness, neglect of duty, quarrelling and brawling. The plaintiffs were churchwardens Nicholas Havelock, Richard Aneley and William Newsam.

Vestry minutes are essentially the minutes of the parish council, and will include lots of names of individuals and references to appointments, as well as agreements of care and lists of parishioners such as men eligible for parish duties and details of illegitimate children. These will often include Overseers of the Poor records.

Overseers accounts, like the vestry minutes, record payments made to the poor and rates charged and received. In January 1800 the monthly meeting of the Hornchurch vestry (today part of the London borough of Havering) faced heavy bills for poor relief. And overseers accounts like these provide vivid evidence of life at the bottom of the heap between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries. Quite apart from the names of individual paupers, they are also a good source for local tradespeople – recording payments to people employed by the parish in various capacities, such as molecatchers, blacksmiths and slaters.

Until the passing of the New Poor Law, the parish was responsible for the welfare of its parishioners. Therefore, before spending money on an individual in dire need, parish administrators wanted to be sure the person was from that parish – and they would often go to some lengths to prove someone was not their responsibility.

These records derive from the Act of Settlement and Removal (1662) which established the need to prove entitlement to poor relief by issuing Settlement Certificates. The certificates proved which parish a family belonged to and therefore which parish had the legal responsibility to provide poor relief if needed. In some cases, if a person was about to or had become a burden on the parish, a Settlement Examination would be carried out to determine whether the person had a legitimate right to residency and relief. If it was found they did not, they would be served a Removal Order. Settlement examinations in particular can be very enlightening as they give mini-biographies of those applying for poor relief. In addition, they can often give you clues about which parish to search next for records of the individual. (There’s a really useful guide to Settlement Certificates and removal orders at: genguide.co.uk/source/settlement-certificatesexaminations-and-removal-orders-parish-amp-poor-law/173/.)

Similarly, records of bastardy were created during a process in which the parish would try to establish the father of an illegitimate child, so the father, and not the parish, could provide for that child. You can find out more about the so-called bastardy bonds in Chapter 4,‘Secrets, Scandals and Hard Times’. In the meantime, to explore some examples try London Lives (londonlives.org) which has a number of case studies and databases drawn from London collections, including bastardy examinations and pauper settlements.

Apprenticeship records are dealt with in Chapter 4, ‘Working Lives’, but in short, so-called pauper apprenticeships were arranged specifically to remove the child as a financial burden on the parish. (Unlike trade apprenticeships, the pauper apprentice indentures were not subject to stamp duty.) This was a feature of the Old Poor Law which allowed the parish officials to bind children as young as 7 to a master. The agreements were drawn up between an apprentice and a master, overseen by the parish, and indentures may survive, or apprentice agreements can be found in the vestry or Overseer of the Poor minutes.

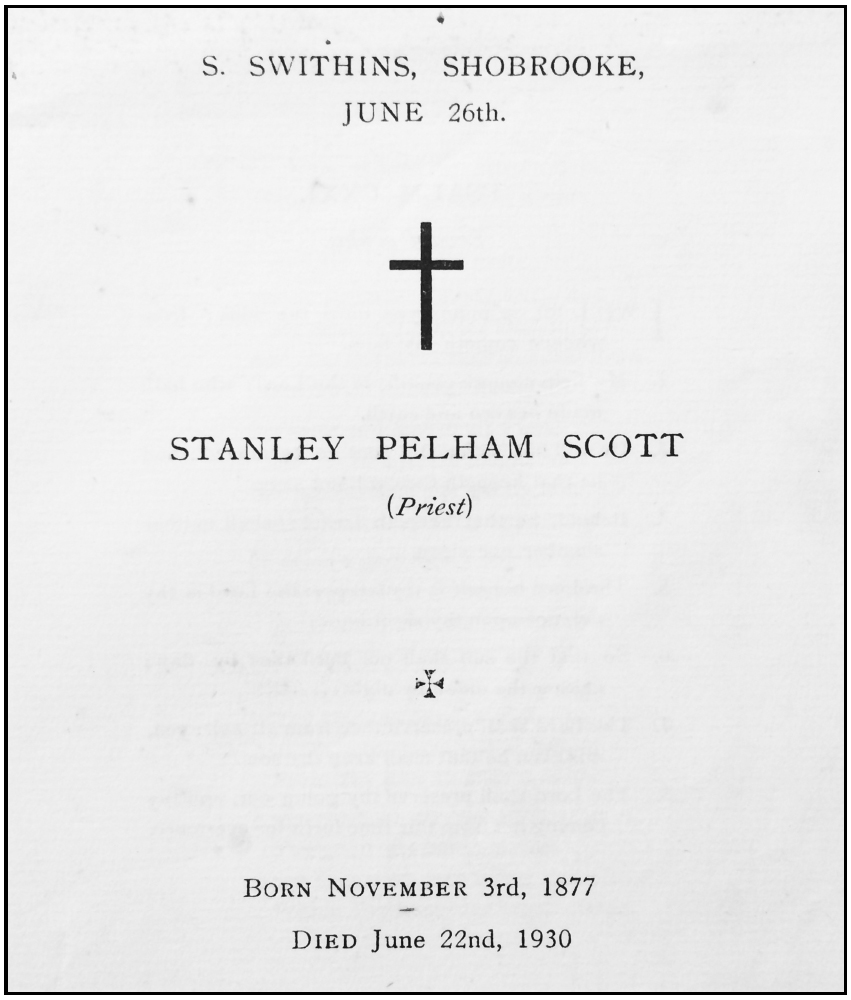

Two valuable pieces of evidence from the author’s family archive. The order of service for the funeral of the Revd Stanley Pelham Scott, which took place in Shobrooke, Devon in June 1930, and a newspaper cutting with the obituary of a forebear – Dublin-born philanthropist Sir William Fry.

Some county collections of these types of records have already been digitised and are available through commercial websites. Some archives have also catalogued and indexed their collections. The website and catalogue of Gloucestershire Archives, for example, has a useful online Genealogical Database, which includes names in the pre-1834 parish overseers’ records – including settlement, apprenticeship and bastardy records. (See www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/archives/article/107400/Genealogical-database.)

Away from the parish chest, there are other potential sources relating to death and burial. Surviving gravestones, for example, can contain information not found elsewhere. They may mention family relationships, will usually confirm dates of birth and death. They can also allow you to make deductions about a family’s relative wealth and status, and may even include designs or heraldic devices that may offer further clues.

Genealogical groups across Britain and Ireland have been transcribing and recording these sources for years, and while some of the data is only available in booklet form, many more can be accessed via CDs, often with images of the original stones. Others have free online indexes to a centralised monumental inscriptions database, and still others have entered partnerships with commercial bodies – including specialists such as DeceasedOnline.

Before the 1850s the vast majority of burials were recorded in the registers of Anglican parish churches (although some Nonconformist chapels had their own burial grounds). An Act of Parliament in 1853 enabled local authorities or private companies to purchase and use land for the purpose of burial.

DeceasedOnline is a good place to view other types of burial records from major municipal cemeteries across England, Wales and Scotland. Again, it’s also worth checking the local authority website as some provide free access to burial records. You may find the likes of this service offered at the Kingston upon Thames Burial Records site, kingston.gov.uk/info/200136/funerals_cremations_and_cemeteries/342/search_our_burial_records), where you can search records from July 1855 to December 2003. While at Belfast Burials (belfastcity.gov.uk/community/burialrecords/burialrecords.aspx) you can search 360,000 Belfast burial records from 3 cemeteries dating back to 1869, and buy images of burial records for £1.50 each. Another useful site is Gravestone Photos (gravestonephotos.com), a growing photographic resource launched in 1998, aiming to photograph and index monuments across the globe (coverage is dominated by England and Scotland).

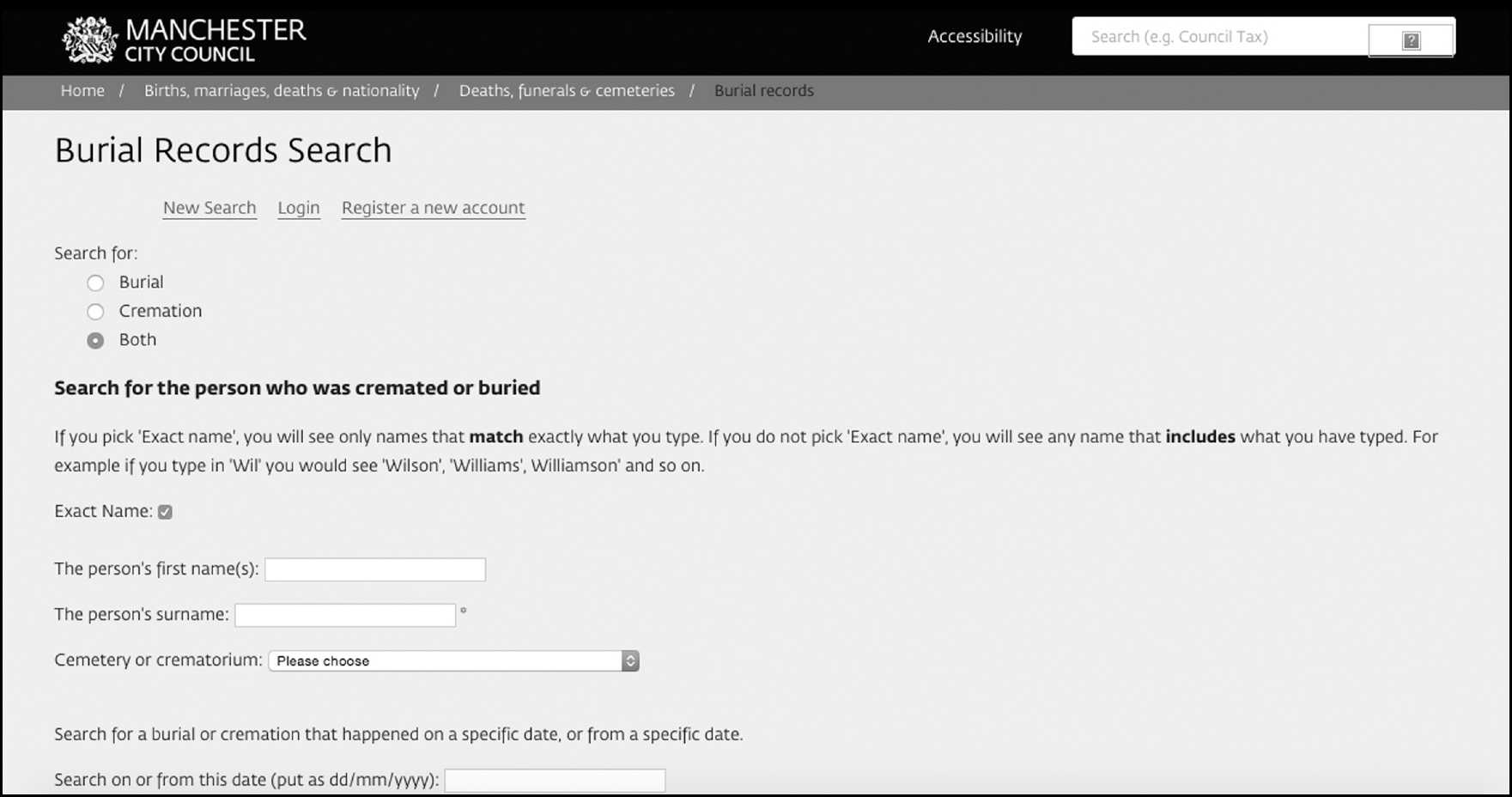

Some local authorities have put municipal burial and cremation records online. This example from Manchester can be explored at www.burialrecords.manchester.gov.uk.

The banns of marriage, commonly known simply as the ‘banns’, are the public announcement in a Christian parish church or in the town council of an impending marriage. Their purpose was to give anyone the opportunity to raise any potential impediment to the marriage.

There were many reasons why individuals might want to marry secretly or in a hurry – if the bride was pregnant or if the groom was on military leave perhaps. Differences in social standing, Nonconformism or simple family opposition to a union might all stand in the way of traditional weddings.

The Church allowed them to circumnavigate the unwanted publicity of calling banns on three successive Sundays by providing a marriage licence – for a fee. And the information given in order to obtain the licence may include detail not available elsewhere. From the early seventeenth century a person applying for the licence (usually the groom) had to provide a bond and an allegation. The allegation was a formal statement containing ages, marital status and places of residence, with an oath that there was no formal impediment to marriage. Then the bond was sworn by witnesses, one of whom pledged to forfeit a sum of money should there prove to be any fraud.

Survival of banns, licences and bonds is patchy, but just as Bishop’s Transcripts can offer a second chance for genealogists looking for parish material, so these related marriage records can give you more opportunities to trace a legal marriage. Where they reside varies, but much of the material may be held in diocesan collections. Through the online catalogue of the National Library of Wales website, for example, you can search some 90,000 bonds and affidavits relating to marriages held in Wales between 1616 and 1837. Similarly, the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections Department houses a heavily used collection of bonds and allegations for marriage licences granted by the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham from 1594 to 1884. And the aforementioned Borthwick Institute for Archives, home to one of the oldest diocesan collections in the country, houses both Bishop’s Transcripts stretching back to 1598 and marriage bonds.

FamilySearch, Ancestry, Findmypast, TheGenealogist and more all boast marriage banns, licences and bonds from various areas. Findmypast’s Staffordshire Collection, which was launched with parish registers between 1538 and 1900, later expanded to include Diocese of Lichfield marriage bonds and allegations. And as the diocese was wider than just Staffordshire, this benefits family historians researching families from Derbyshire, north Shropshire and north Warwickshire.

In Scotland too the proclamation of banns was the notice of contract of marriage, read out in the kirk before the marriage took place. Couples or their ‘cautioners’ (sponsors) were often required to pay a ‘caution’ or security to prove the seriousness of their intentions. And forthcoming marriages were supposed to be proclaimed on three successive Sundays, however, in practice, all three proclamations could be made on the same day on payment of a fee. All this and more detail about Scottish OPR Banns and Marriages can be found via the relevant ScotlandsPeople page (you’ll find the link on the left-hand homepage menu).

Parish Chest Records: familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Parish_Chest_Records

Ancestry: ancestry.co.uk/parish

ScotlandsPeople: scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Findmypast: search.findmypast.co.uk/search-united-kingdom-records-in-birth-marriage-death-and-parish-records

Bishop’sTranscripts, Devon Archives: devon.gov.uk/bishops_transcripts.htm

Deceased Online: deceasedonline.com

Leading commercial specialists, providing data from graveyards and municipal cemeteries across the UK.

Gloucestershire Archives, Genealogical Database: www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/archives/article/107400/Genealogical-database.

Anguline Research Archives: anguline.co.uk

Republishes rare books on CD/PDF download, including many volumes of UK parish transcriptions.

Gravestone Photos: gravestonephotos.com

Interment: interment.net

Free library of Cemetery Records Online, drawn from cemeteries and graveyards across the globe.

Burial Inscriptions: burial-inscriptions.co.uk

Sheffield Indexers: sheffieldindexers.com/BurialIndex.html

Death & Burial, GenesReunited:

Manchester Burial Records: www.burialrecords.manchester.gov.uk

Belfast Burials: belfastcity.gov.uk/community/burialrecords/burialrecords.aspx

GraveMatters: gravematters.org.uk

Annal, David and Audrey Collins. Birth, Marriage and Death Records: A Guide for Family Historians, Pen & Sword, 2012

Grenham, John. Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, Gill & Macmillan, 2012

Heritage, Celia. Tracing Your Ancestors Through Death Records: A Guide for Family Historians, Pen & Sword, 2015

Humphery-Smith, Cecil R. The Phillimore Atlas and Index of Parish Registers, Phillimore, 2002

Probert, Rebecca. Marriage Law for Genealogists, Takeaway Publishing, 2012

Raymond, Stuart A. Tracing Your Ancestors’ Parish Records, Pen & Sword, 2015

Tate, William Edward. The Parish Chest, Phillimore, 2011