The Disappearance of the Medieval Lantern

The Fate of the Lantern Tower

The lantern does not appear in any view of the Abbey after 1532, and it was presumably lost shortly after that date (or perhaps even earlier: see p. 24). It is improbable that the loss resulted purely from the decay of the carpentry, but a fire caused either accidentally or by a lightning strike could have precipitated destruction. However, it is inherently unlikely that an incident as major as this would have passed without being noticed in the written record, and we should perhaps seek another cause. Structural failure in the crossing was reported by Wren when he carried out a survey in 1713, and this was potentially the problem that precipitated the removal of the lantern (see below, p. 31).

Wren recorded that the crossing piers had all bowed, and the adjacent arches of the triforium arcades were fractured. Later references to the necessary repairs imply that the crossing arches were also distressed, which must inevitably have occurred if the piers themselves had moved to any significant extent. The date at which this failure occurred cannot be precisely established, but it was well before the eighteenth century. If the corbelling or squinch-arches carrying the four angled sides of the masonry octagon had fractured, then the whole superstructure would have been endangered. Structural measurements and archaeological observations indicate that movement of the north-west crossing pier caused the principal damage. The most expeditious method of dealing with the problem was simply to demolish the lantern. If the crossing piers and arches were failing in the early sixteenth century, it would have been an understandable reaction to remove as much weight as possible from them, in the belief (albeit mistaken) that this was the cause of the problem. In reality, it may have exacerbated the situation. We shall return to this subject later (p. 58).

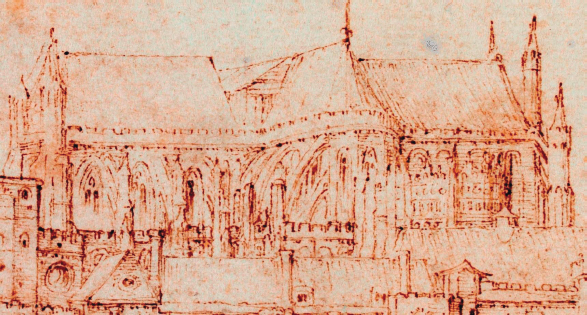

A view of the Abbey from the east, formerly attributed to Wenceslaus Hollar and assigned to c. 1630, has recently been redated to the mid-sixteenth century.34 Its depiction of the Abbey’s roofscape is very revealing. It does not show any upstanding feature over the crossing, but a low-pitched roof linking the ridges of the nave and eastern arm; the south transept roof stands independently, in an ungainly manner, and with a V-shaped gap, or gusset, between it and the main east–west roof. [29] Presumably, there was a similar feature on the north side too. The anonymous artist is most unlikely to have invented this incongruous arrangement of junctions between the roofs: arguably, he captured the moment when all the timber and much of the masonry of the lantern had been taken down, and a low-pitched, temporary roof covering had been, or was being, installed over the crossing. The arrangement depicted in this view could not have obtained for long, and it would certainly not have stood like this since the 1250s. In the first place, it would have been well nigh impossible to keep the crossing (and hence the quire) watertight, but even more significant is the fact that, being entirely without lateral support from a crossing tower, the trussed rafters of the transept roofs were very vulnerable: they would have racked within a few years, and partial collapse would doubtless have ensued. The original design of the transept roofs necessitated their being supported at both ends by masonry (i.e. by the crossing tower and the transept gables, respectively).35

29 Anonymous, mid-sixteenth century. Detail from a drawing showing Westminster Abbey from the east, with a temporary configuration of roofs over the crossing after the medieval lantern had been removed. This view appears also to show a fragment of the lower part of the south-east stair-turret. © Victoria and Albert Museum: E.128–1924

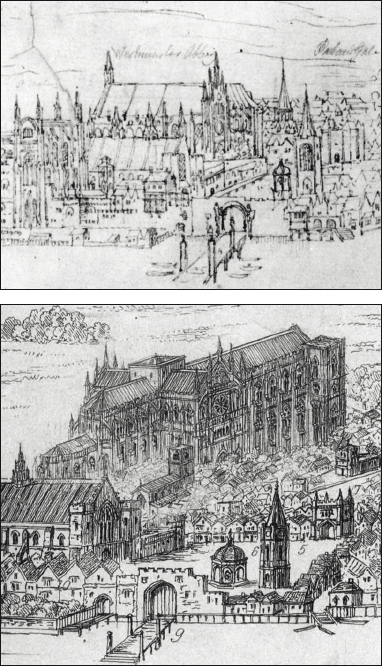

30 Van den Wyngaerde, c. 1544.

A. Detail from his original Panorama, showing Westminster Abbey and Hall from the north-east. No tower or other feature is indicated over the crossing. © Bodleian Library, Oxford.

B. Mid-nineteenth-century redrawing of his birds-eye view of Westminster Abbey from the northeast, showing a box-lantern over the crossing which does not appear in the original illustration. Mitton 1908

Early Views of the Abbey

The next piece in the Tudor jigsaw comes from the birds-eye view of Westminster by Anthonis van den Wyngaerde, which forms part of his Panorama of London, drawn in c. 1544.36 [30A] Since the original drawing is very faint, it was copied and engraved several times in the nineteenth century,37 and one version in particular has frequently been reproduced in subsequent works.38 It shows the Abbey with a square ‘box-lantern’, projecting slightly above the ridges of the four main roofs. The lantern has a plain coping and a pyramidal roof of low pitch. There are two small windows in each face, but no stair-turrets at the angles. [30B] Superficially, the structure depicted could be mistaken for the present lantern, except for the absence of corner-turrets. However, there are major discrepancies between the two versions of the drawing, since Wyngaerde’s original does not show anything projecting from the roof of the Abbey church. In fact, it is extremely sketchy, and the only prominent detail is the pinnacled gable of the north transept; its counterpart on the south is also depicted with a tall finial. Numerous alterations and introductions of non-original material are found in the Victorian re-drawing, and the ‘box-lantern’ is wholly fictitious, being merely a re-working of Hawksmoor’s tower.39

To recapitulate: there are fortuitously three views of the Abbey, all dating to the first half of the sixteenth century and showing the crossing in markedly different states. Although the Islip drawing dates from 1532, it records an event which took place in 1509, when there was a staged lantern tower.40 The second drawing is undated, but appears to record the transition between the destruction of the octagonal lantern and the reroofing of the crossing. The third illustration, dating from c. 1544, shows the Abbey church without any feature on its roof.

Various views of Westminster Abbey dating from the seventeenth century exist, and none shows anything projecting from the roof above the crossing. Hollar’s north and south prospects (1654), for example, simply depict the four main roof-ridges all meeting over the centre of the crossing.41 Neither does a lantern appear on Keirincx’s prospect of Westminster (1625),42 nor on Hollar’s general views, although a small feature that seems to be a roof dormer occurs in the north-east angle of his drawing of 1647.43 Thus, the evidence seems conclusive: the later medieval lantern and at least some of the masonry of the thirteenth-century octagonal base upon which it sat were removed sometime between c. 1509 and 1544, and, after an initial patching-up of the crossing, a new roof was erected to infill the space and connect effectively with the four abutting high roofs.

31 Wren, 1715. Plan of the crossing at eaves level, as then existing, showing the bases of the thirteenth-century angle-turrets and a pair of narrow openings in each wall (east is at the top). Overdrawn on this are two alternative versions for a proposed spire (dodecagonal on the left, and octagonal on the right), and in the centre is a plan at a smaller scale, showing the proposed arrangement of the parapets at the top of the tower. Also on the same sheet is an internal elevation of the east side of the crossing, as modified in the sixteenth century; the dotted line represents a ceiling of elliptical form. Bodleian Library, Oxford: Gough Mss. Wren Society 1934

The Earliest Architects’ Drawings

However, the story may not be quite as straightforward as it appears because various features relict from the former lantern are recorded in two architects’ drawings of the early eighteenth century, and from these further details of its construction can be gleaned. The first is a plan of the crossing at eaves level, made in 1715, overlaid upon which is Wren’s proposal to build a tower and spire.44 [31] The walls of the crossing were each pierced by a pair of narrow, lancet-headed openings (60 cm wide). These never functioned as windows because they were set low in the walls, were unsplayed and opened only into the adjacent roof spaces. They were almost certainly associated with the thirteenth-century construction, and are suggestive of a gallery around the interior of the crossing, at the base of the lantern stage.45

The plan is accompanied by an internal elevation of the east side of the upper part of the crossing, from which additional important details can be gleaned. It shows that the walls and octagonal corner-turrets stood to a height of 18 ft (5.5 m) above eaves level, and that the crossing was capped with its own roof. That was noted by Wren as being of chestnut, and it comprised two trusses intersecting at right-angles, anchored by wall-posts rising from corbels at the centre of each side. Although certainty cannot obtain, the structure gives the appearance of being sixteenth or perhaps seventeenth century in date. The crossing was ceiled with a plaster dome of elliptical profile, just above the level of the lancet openings in its walls.46 Indeed, most contemporary allusions to the unrestored crossing refer to it simply as ‘the dome’.

The plan records that the walls of the crossing, above eaves level, were reduced in thickness from 5 ft to 3 ft, but whether the resultant offset (which still exists) was an original features, or was introduced subsequently, is unknown. Substantial parts of the octagonal turrets clearly survived at all four corners of the tower, and those on the north-east and south-west had newel stairs in them; the others may have been either solid or hollow.47

The second drawing is by Wren’s assistant, William Dickinson, and is dated 8 June 1724. It comprises a sectional elevation of the upper part of the crossing, upon which a new king-post roof had been constructed by Wren. [32] He must have regarded this as a short-term measure, since he clearly had more ambitious ideas for the future treatment of the crossing. The domed plaster ceiling is again indicated, but superimposed upon the elevation is an arrangement of three arches, clearly of masonry and evidently indicative of some kind of vaulted ceiling. This drawing has the appearance of being a proposal to rebuild the crossing piers (see below, p. 32) and to replace the plaster ceiling with a stone vault, as precursors to the eventual erection of a tower and spire. However, it is not easy to reconcile these architects’ drawings with an internal view of the quire in c. 1700, which clearly shows three of the ribs of an octopartite vault over the crossing, where, at that date, we should expect to see a domical plaster ceiling.48 [33] A simple explanation, which accommodates all the evidence, might be that the ribbed vault was a sixteenth-century creation in timber and plaster, and that this was replaced in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century with a simple domical ceiling.49

What conclusions can be drawn from this disparate and partially conflicting evidence? The late medieval octagonal lantern was destroyed sometime between c. 1509 and 1544, leaving in situ the base of Henry III’s lantern, including substantial parts of its four octagonal corner-turrets. The remains were roofed in an ad hoc fashion, as glimpsed in the mid-sixteenth-century drawing. [29] The upper part of the crossing now became a windowless box with paired openings into the adjacent roof voids. A certain amount of reconstruction, squaring-off the angles of the octagonal lantern, and integrating the corner-turrets, seems to have taken place in the sixteenth century, making the structure easier to roof. The reduction in thickness of the side walls may have occurred at the same time. The masonry of the box-like top to the crossing extended only as high as the window sills in the present lantern, and the apex of its roof – which must have been pyramidal in form – rose to approximately the same level as the ridges of the adjacent medieval high roofs.

Thus, by the mid-sixteenth century there was no lantern or other structural projection above the ridge-line of main roofs of the Abbey, a fact confirmed by numerous seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century topographical views. However, what these views all failed to record is that the medieval masonry at the corners of the crossing would have protruded at the angles between the four high roofs. It is not surprising that such archaeological detail, which made no significant impact on the overall appearance of the church, was not recorded by most of the topographical artists, who simplified the roof-lines.

32 Dickinson, 1724. Elevation of the interior of the crossing, showing the Tudor box-like top, with its elliptical ceiling and Wren’s new but temporary roof. The proposed reconstruction of the crossing piers and insertion of a stone vault are also shown; these features anticipated the erection of the great tower and spire seen in Figure 34. WAM (P)911