I am writing this late in the evening on July 4. My daughters are in bed. The sizzle and crackle of fireworks are over. But the music from PBS’s coverage of the concert outside the US Capitol building still rings in my ears. The show combined patriotic music, words from well-known American heroes, and photos of iconic American images—the Statue of Liberty, the Lincoln Monument, the Grand Canyon, the Golden Gate Bridge, and so on.

O beautiful for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain.

I feel a swell of emotion. Independence Day, for me, brings with it a sense of nostalgia, almost like a birthday does. A birthday evokes memories of childhood. July Fourth evokes memories of, well, how do you describe it? Memories of America? What it is, what it represents, what we want it to be.

I don’t recall when I first became conscious of my affection for the United States. Maybe it was amid the glint of sparklers on the Fourth of July as a child, or during an elementary school lesson on Abraham Lincoln, or into my third helping of sweet-potato casserole at Thanksgiving, or while watching a Cubs game at Wrigley Field in high school.

I do remember discovering Walt Whitman’s poem “I Hear America Singing” in college and being enlivened by it.

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear . . .

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else . . .

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.1

I also remember discovering the American composer Aaron Copland in college. His ballets and orchestral suites inspired thoughts of Appalachian songs, prairie nights, and Western hoedowns. To this day when I hear his music, I can feel a deep yearning for decades I’ve only read about and places I’ve only seen in black-and-white photographs—all deeply American.

These snapshots are some of the symbols of my own love of country. What has been difficult for me over the last decade or two, however, has been to watch a growing divide between America and my Christianity. I might even say the relationship is becoming downright contentious.

CONTENTION AND DIVISION

I was in Southeast Asia several weeks ago spending time with a friend, Michael. Michael is an American missionary, and his family has been absent from the United States for more than a decade. Over dinner one evening we strayed into politics.

“I keep up on the news,” he said. “But what’s it really like?”

Missionaries are kind of like cultural time capsules. They leave the homeland, and their sense of the homeland’s trends and styles gets frozen in time. “Why are you wearing baggy pleated pants, brother? It’s not the 1990s.” Keeping up on the news, of course, doesn’t give someone a feel for what it’s like living in the States.

“Honestly, it’s really intense,” I said in answer to his question. “There’s a lot of division and contention.” I then spent several minutes trying to give Michael a feel for that division.

For instance, the political Left and Right used to talk and reason with each other. Now they just shout. When a liberal guest lecturer at the University of Notre Dame was asked if she could find common ground with conservatives on race and gender, she answered, “You cannot bring these two worlds together. You must be oppositional. You must fight. For me, it’s a line in the sand.”2

Then there was the man who spent $422 million bankrolling the campaign to make same-sex marriage legal in all fifty states. When asked about his plans, he replied, “We’re going to punish the wicked.”3

And there was the Harvard law professor who described his posture toward conservatives: “The culture wars are over; they lost, we won. . . . My own judgment is that taking a hard line (‘You lost, live with it’) is better than trying to accommodate the losers.”4

“It’s a nasty time. It’s a nasty time,”5 concluded the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia as he thought about the modern climate and recalled how Republican and Democrat powerbrokers fraternized and clinked glasses at Washington, DC, dinner parties in the 1970s and ’80s. This “doesn’t happen anymore.” Scalia was elected to the Supreme Court in 1986 by the US Senate in a 98–0 vote. Today’s Supreme Court nominee battles, however, are nearly straight party-line votes.

Scalia made these comments in 2013. Think of what’s transpired since: the Supreme Court’s legalization of same-sex marriage in the Obergefell case, the legal showdowns between LGBT rights and religious liberty, the explosion of police-brutality videos and the emergence of Black Lives Matter, the sudden prominence of the transgender movement, the rise of the alt-right, the growing divide between globalists and nationalists, and the still-bewildering 2016 elections.

Meanwhile, a conservative lobbying organization in Washington sent out a fundraising e-mail shortly after Donald Trump’s election. With all caps and bold-faced warnings, it promised the “radical Left won’t accept” the election’s results but “will subvert the future.” The Left has “already violently protested the election” with “money from Hollywood-Washington elitists.” Everyone who loves “faith, family, and freedom” should therefore watch out for “the Left’s massive attempt to DECEIVE, INTIMIDATE, AND SIDETRACK lawmakers.” It would “try EVERY POLITICAL TRICK IN THE BOOK.” But you can “fight back” and help win “the 2017 policy war.” So “donate now.”

Whether or not you agree with this release, consider its language: radical, subvert, violently, deceive, intimidate, fight, war. I asked a friend who works at a similar religious-right organization whether such strident language was typical.

“It’s the standard vernacular,” he said. “It’s us versus them. Either we’ll take our country back (for God) or they (the progressive liberals) will take over.” He also explained, “By and large politics is no longer about people participating in a shared project of societal order. There is very little desire to actually persuade. The strategy nowadays is to acquire enough political power to have your way. There may be more groups that are more nuanced and charitable in their language, but groups on the Far Right and Left set the tone on the ground.”

In fact, Pew Research shows that Democrats are more left-leaning and Republicans more right-leaning than they were two decades ago. And both increasingly see each other as an existential threat to the nation.6

The contentiousness is hardly limited to DC interest groups. Ask Jordanna. She’s twelve. Her parents are Christians, and her father worked for a previous Republican administration. Those two facts alone have made her the butt of jokes and ridicule in her public school. Meanwhile, the teachers and administration increasingly advocate for Gay Pride and other such causes. Shortly after the 2016 elections, Jordanna’s school (teachers and students) participated in an anti-Trump march. Jordanna’s parents were not Trump supporters, but they asked if their daughter could be exempted from the march. Permission was granted, but Jordanna became the lone standout. Students bullied. Old friends stopped speaking to her. “Why do we have to be so different?” she pleaded with her father through tears.

I didn’t give Michael all these examples as I laid out how things have grown increasingly divided, but a number of them were fresh in my mind. “It’s as if we are in a contest between two warring planets—the Left versus the Right,” I said. “Or perhaps it’s more like one planet that has broken into multiple pieces, with guns shooting every which way as the pieces drift apart. Remember that game Asteroids on the old Atari systems from when we were kids? That’s what it’s like.”

One thing is certainly true: America is in the middle of an identity crisis. Ask those wearing the red “Make America Great Again” ball caps and those holding “Black Lives Matter” picket signs what unites us, and you’ll hear pretty different answers.

INSIDE THE CHURCH TOO

“What’s even sadder,” I went on to explain to Michael, “is how much these battles have shown up among Christians and in our churches.”

Consider the 2016 presidential election. Among evangelicals it felt like someone dropped a lit match into a box of firecrackers. Tweets whistled like bottle rockets, and Facebook posts popped like cherry bombs. Pastors who had never in their careers endorsed a political candidate from the pulpit suddenly felt conscience-bound to speak. Christian leaders with a national stage did the same thing.

Michael had picked up this much just from watching the Web. His local friends often queried him about the elections. But what Michael couldn’t know firsthand was the quibbling and tension building inside of churches too. One friend in another part of the country shared in an e-mail, “We were having dinner with some friends from our church the other night. I offered a few of my thoughts on Trump. People got pretty mad. All this is crazy! I have to quit talking about the elections. They’re really putting a damper on our friendships. Too dangerous.”

The media, popcorn in hand, noticed all this bickering. Headlines buzzed: “Donald Trump Reveals Evangelical Rifts That Could Shape Politics for Years” (New York Times, 10/17/16) and “Evangelical Christians Are Intensely Split over Trump and Clinton” (Faithwire, 10/17/16).

The elections especially divided Christians by ethnicity. Whites leaned hard toward Trump, nonwhites marginally toward Clinton. After the election, African American friends of mine wanted to be “done” with evangelicalism.

“All these tensions showed up in my own Sunday school classroom,” I told Michael. That fall I taught a class on Christians and government in my church, which gathers six blocks away from the US Capitol building. The Sunday after the election I opened the class with a few comments on our need for unity in the gospel. An older black woman raised her hand and lamented that she had felt no empathy from the white majority. A middle-aged white woman responded by declaring all Democrats “evil.”

Wait, why did I choose to teach this class?

“My concern with all this was not that Christians might disagree on which candidate was best,” I explained. “It was the emotional temperature of the disagreements. Trust began breaking down. Relationships were jeopardized. Christian liberty was threatened.”

What I didn’t get into with Michael was something I thought about later. If we truly stop and consider where all this strife came from, we’d see that the confusion and conflict American evangelicals experienced during the 2016 elections cannot be isolated to that relatively short moment in time. They were symptoms of larger confusions, larger troubles.

Pan the camera back and consider the perspective of the last few decades. Christians feel that they have been losing the culture wars on front after front. Born in 1973, I don’t remember the sexual revolution of the 1960s or the nationwide legalization of abortion the year of my birth. Yet I remember firsthand the successive waves of moral changes throughout my childhood, college years, and beyond: the positive portrayal of a cohabitating couple on television in 1984, a children’s book about two lesbian mothers in 1989, school board debates over the distribution of condoms in the early Clinton years, and the growing number of gay characters on television shows and movies in the ’90s and ’00s. Add the judicial doubling-down on abortion in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Add the state-by-state advance of same-sex marriage laws starting in Massachusetts in 2004, culminating in a nationwide decision with Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015. Add the battles over religious liberty this created, such as when corporate America threatened commerce in Indiana due to Governor Mike Pence’s proposed Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Also throw in the political controversies that quickly followed in 2016 over transgender bathrooms, as well as the workplace controversy over gendered pronouns shortly thereafter.

And there you have my generation’s cultural autobiography.

Little by little Christians have felt pushed to the outskirts of whatever America is becoming. We still light the sparklers, enjoy the sweet-potato casserole, and root for our ball teams. But something is changing—has changed. It’s beginning to feel like a different America. Like the media is sneering, the universities are stigmatizing, the government is sidelining, and Hollywood is scoffing. Religious liberty, which is explicitly written down in the Constitution, seems to be losing in court to erotic liberty, which is nowhere near the Constitution.

Amid our cultural war losses and dropping church attendance numbers, Christians have bickered about how to best engage the culture. Some want to strengthen the evangelical voting bloc. Others want to pursue social-justice causes. Still others would leave the public square to the pagans and get on with the so-called spiritual work of the church.

Now zoom the camera back in on the 2016 elections, where disagreements like these finally boiled over. After several decades of losses, evangelicals felt a growing sense of desperation. It was like watching the fourth quarter of a game where a team that fully expected to win suddenly realized how far behind it was. Players began to take higher risks. The risks didn’t pay off. The team became more anxious. Tempers flared. More fouls, more whistles. Players and coaches started blaming one another. Team unity broke down.

Perhaps the saddest example of this inside American churches remains the ethnic divide. Black churches exist in America in large part because whites pushed them out in centuries past. Since the 1980s, many whites have tried to welcome blacks, but it’s back into their white churches. The message people of color often hear remains, “Give up your cultural preferences so that I can keep mine.”

It’s like the explanation I gave of my enjoyment of Independence Day. I can talk to you about what I think it means to be “American.” But I speak as a European American. Ask an African, Asian, Latino, or Native American what the noun American means. Certainly people within each of these groups will not share uniform perspectives. Still, you may hear certain family resemblances inside each group as they tell their versions of the story. In chapter 3, for instance, I’ll point to one African American pastor who feels internal conflict over the Fourth of July holiday. His regard for America is less nostalgic, more painful than mine.

We all bring different perspectives, and frankly the majority and the minority have a hard time hearing each other. We use terms like guilt and privilege and justice, but we mean different things by them.

It’s my sense that one of Satan’s greatest victories in contemporary America has been to divide majority and minority Christians along partisan lines. White Christians lean heavily right. Black Christians lean heavily left. (Honestly, I’m unsure about Latino, Asian, and Native American evangelicals.) And this partisan divide hurts trust and breaks down Christian unity even further.

Perhaps it’s time for Christians to rethink faith and politics?

Goal 1: Rethinking Faith and Politics

This is one of the first goals of this book: to rethink faith and politics from a biblical perspective. At one point the working title for this book was Political Restart.

There are a number of books on faith and politics being published at the moment, some advocating for a kind of withdrawal, others for a more active engagement. Such books have their place, and I’ve benefited from them. Yet many of them depend on the author’s ability to read the moment and offer his or her best advice about responding to it. I, too, am looking at the present divided and contentious moment in American life. But that’s not my primary interest. Instead, I want to help us build on something more solid and certain. That’s not my wisdom. It’s God’s, as revealed in his Word.

Let me characterize my first goal this way. Once a year, my friend Patrick and his wife rethink their financial priorities through what he calls “zero-based budgeting.” With zero-based budgeting, everything in the family budget is out until they can justify putting it back in. Does their family need that size of a house? Should they give more money to the church? They don’t take anything for granted. The alternative is “incremental budgeting,” where you accept everything from last year’s budget but then add or subtract items in bits and pieces.

There is wisdom in both approaches, but it serves a family to occasionally rethink their priorities from scratch. One year Patrick and his wife decided they had “too much” house. So they did a radically un-American thing: they downsized!

I want to take a zero-based budgeting approach to Christianity and politics in this book. Assuming we take nothing for granted, what might a biblically driven vision of politics look like? What are the biblical principles that we must hold with a firm grip? What are the matters of wisdom and judgment to hold with a loose grip? And what should we discard altogether? Too often, we cling to our political judgments with as much certainty and zeal as we maintain God’s.

I once asked a friend who takes his political opinions very seriously whether he assumed Jesus would agree with his positions on health care and tax policy. I asked almost as a joke, but he said yes! I would say, in response, that confusing our judgments with God’s turns our judgments into idols, which in turn divides the church and leads to injustices inside and outside the church.

It’s easy for Christians (as with all people) to approach the topic of politics like incremental budgeting. We take the views, assumptions, and practices into which we were born for granted. Then we look for ways to make marginal improvements. And, frankly, much of the time, that is the better approach, especially if you believe there is wisdom in the past and you don’t assume that you or your generation knows better than everyone who came before. I’m not a political radical. I’m not calling for a revolution. I don’t want to unlearn all the good things we have learned in the last several thousand years of human history about freedom and justice, democracy and rights.

Still, as Christians who prize God’s wisdom above that of men and women, we should strive to stop from time to time and say, “Wait a second. Is this biblical?” and be willing to throw anything and everything off the boat if necessary. And we should do this even with the things that our nation, our tribe, and our people regard as most precious. An unwillingness to try may indicate a political idol, even if it’s not as visible as the statue built by Nebuchadnezzar.

More foundationally, I am concerned that sometimes we let principles of Americanism determine the way we read Scripture, rather than letting Scripture determine how we evaluate principles of Americanism. It’s like we have a big pot of stew that has been simmering for centuries and contains all our favorite phrases, like so many potatoes, carrots, and chunks of meat:

• “render to Caesar”

• “be subject to the governing authorities”

• “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”

• “no law respecting an establishment of religion”

• “wall of separation between church and state”

• “of the people, by the people, for the people”

• “I pledge allegiance to the flag”

• “in God we trust”

The political lines of Scripture cook together with the sacred lines of American history, each flavoring the other.

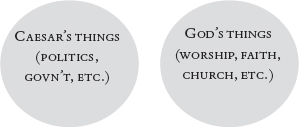

For instance, think of that favorite biblical phrase for many American Christians: “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matt. 22:21). My sense is that most American Christians interpret that phrase like this: you have the domain of government and politics in one circle and the domain of God and church and religion in another circle.

Hold on. Is that what Jesus was saying? Might we be letting certain American ideals overdetermine our understanding of Scripture?

On the one hand, Jesus was surely telling these Jews under Roman rule to respect their Roman ruler. Many in Jesus’ day were saying that a non-Jewish government was illegitimate and that they needed a Jewish king again. Jesus was saying otherwise. The Old Testament’s church and state arrangement—to risk an anachronism—was coming to an end. Americans rightly get this, and we rightly separate church and state.

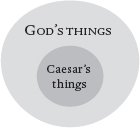

On the other hand, consider the verse in context. Jesus looked at a coin and asked whose image was on it. Answer: Caesar’s. Okay, but in whose image was Caesar? Answer: God’s. Which would mean: giving to God what is God’s includes Caesar! Jesus was not pushing God into the private domain, concluded New Testament scholar Don Carson. Rather, “Jesus’ famous utterance means that God always trumps Caesar.”7 The real picture is like this:

Fast-forward to Matthew 28, where Jesus said he possesses all authority in heaven and on earth. Jesus will judge the nations and their governments. They exist by his permission, not the other way around, even if states don’t acknowledge this fact (John 19:11; Rev. 1:5; 6:15–17).

The separation of church and state is not the same thing as the separation of religion and politics. But it’s not until we dump the pot of stew onto the counter and examine each chunk a little more carefully that we’ll see this.

That’s why this book’s subtitle mentions “rethinking” faith and politics. We are dumping the stew onto the countertop and starting over. Mixing metaphors, we are adopting a zero-based budgeting strategy for thinking about politics. The goal is not to discard everything we’ve learned, but it is to make sure we are thinking rightly, acting rightly, loving rightly, even worshipping rightly in our political lives.

When you’re done with the book, you won’t have gained much if you are relying on my wisdom. You want to rely on God’s. It’s a much steadier place to stand.

In that sense, I hope the book proves helpful not just for early twenty-first-century Americans, even though that’s the context for the conversation. I hope it will prove useful for Christians in every nation.

Goal 2: Investing Our Political Hopes Firstly in the Church

If the first goal of the book is to help us rethink religion and politics, the second goal is to encourage us all to invest our political hopes first and foremost in our local churches. That’s why another working title I discussed with the publisher was Church Before State.

Perhaps this goal surprises you. The church isn’t political, is it? Make no mistake, rethinking things means blowing up a few of our present paradigms. And this is one of the first things I want to blow up. Church and state are distinct God-given institutions, and they must remain separate. But every church is political all the way down and all the way through. And every government is a deeply religious battleground of gods. No one separates their politics and religion—not the Christian, not the agnostic, not the secular progressive. It’s impossible.

Let me give you a taste of what I mean about the political nature of the church with a true story about one of my fellow church members, Charles. Charles is a Washington, DC, speechwriter. He has written speeches for cabinet members, party chairmen, and other DC insiders. Charles’s work, to be sure, puts him at the center of American politics.

Charles also spends time with Freddie. Freddie, who was homeless, became a Christian and joined our church. After several good years, the church discovered Freddie was stealing money from members to support a drug addiction, so they removed him from membership. That’s when Charles entered the picture. He began reading the Bible with Freddie, and little by little, Freddie began to repent. Eventually Charles helped Freddie stand before the entire church, confess his lying and stealing, and ask for forgiveness. The church clapped, cheered, and embraced Freddie. Charles and Freddie cried for joy.

Here’s the GDP-sized question: Which Charles is the “political” Charles? The speechwriter or the disciple-maker? To ask it another way, which Charles deals with welfare policy, housing policy, criminal reform, and education? Answer: both. In fact, Charles will tell you that the political life of the disciple-maker fashions and gives integrity to the political life of the speechwriter. It’s the same man working, the same King ruling, the same principles of justice and righteousness applying, the same politics in play.

This speechwriter has many political hopes for better laws and fairer practices. But the greatest of his political hopes comes to life in the congregation. The local church should be a model political community for the world. It’s the most political of assemblies since it represents the One with final judgment over presidents and prime ministers. Together we confront, condemn, and call nations with the light of our King’s words and the saltiness of our lives.

Unlike Charles, however, many Christians in America continue to invest their greatest political hopes in the nation. Since colonial times, we have called the nation “a city on the hill.” Since Abraham Lincoln’s day, we have asked our leaders to provide “a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Yet is it possible that all the contention and division Christians presently face is the catalyst God means to force some of us to rethink where our political hopes really lie?

Just think: Where do we first beat swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks? Where should love of enemy first dissolve a nation’s tribalism? Where should Lincoln’s just and lasting peace first take root and grow?

Answer: in our local churches.

Conversion makes us citizens of Christ’s kingdom, places us inside embassies of that kingdom, and puts us to work as ambassadors of heaven’s righteousness and justice. Churches are the cities on hills, said Jesus. Not America.

Goal 3: Learning to Be Before We Do

This brings us to the third goal of this book. If our political hopes should rest first in our churches, we must learn to be before we do.

My church gathers six blocks from the US Capitol. It is filled with young people like Charles who moved to DC wanting to make a difference by working in various spheres of government. And their work matters. After all, good governments are prerequisites to the rest of life, including the life of the church.

But as one of the elders, or pastors, of the church, I often remind our Hill staffers, K Street lobbyists, and military officers that real political action starts in the teaching ministry of our church and then flows outward from there—from our relationships with other members, to our families, our workplaces, and beyond. First be, then do. Don’t tell me you’re interested in politics if you are not pursuing a just, righteous, peace-producing life with everyone in your immediate circles.

Paul asked the Jews of his day, “You who preach against stealing, do you steal?” (Rom. 2:21).

I’ve got a few questions of my own.

You who call for immigration reform, do you practice hospitality with visitors to your church who are ethnically or nationally different from you?

You who vote for family values, do you honor your parents and love your spouse self-sacrificially?

You who speak against abortion, do you also embrace and assist the single mothers in your church? Do you encourage adoption? Do you prioritize your own children over financial comfort?

You who talk about welfare reform, do you give to the needy in your congregation?

You who proclaim that all lives matter, do all your friends look like you?

You who lament structural injustices, do you work against them in your own congregation? Do you rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep?

You who fight for traditional marriage, do you love your wife, cherishing her as you would your own body and washing her with the water of the Word?

You who are concerned about the economy and the job market, do you obey your boss with a sincere heart, not as a people-pleaser but as you would obey Christ?

You who care about corporate tax rates, do you treat your employees fairly? Do you threaten them, forgetting that he who is both their Master and yours is in heaven and that there is no partiality with him?

Finally, as you share your opinions about all these issues on social media, do you gladly share the Lord’s Supper with the church member who disagrees? Do you pray for his or her spiritual good?

“All politics is local,” said former Speaker of the US House of Representatives Tip O’Neill. He spoke better than he knew.8

Politics should begin with our putting away the verbal swords we might be tempted to wield against church members who vote differently than we do. Any political impact our fellow members make in and through the church will last forever. I love how my church’s senior pastor Mark put it: “Before and after America, there was and will be the church. The nation is an experiment. The church is a certainty.”

When I say we must be before we do, I mean the local church should strive first to live out justice, righteousness, and love in its life together. Then it can commend its understanding of justice, righteousness, and love to the nation.

With these last two goals I want to shift our focus from redeeming the nation to living as a redeemed nation, like Charles and Freddie together. Our congregational lives should tutor us in the justice and love that God desires for all humanity. And then the lessons we learn inside the church should inform our public engagement outside of it.

God establishes governments to build the platforms of peace and basic justice on which we can live our lives. Christians, as they have opportunity in government, should therefore work for principles of justice. Yet God establishes churches, among other reasons, to mark off the people who will present a fuller picture of justice. The work of Christians in Washington, your state capitol, your town hall, or your school board means little without the radiating glow of kingdom embassies behind them and the ambassadorial witness of every Christian.

Goal 4: Preparing for Battle and for Rage

As the church moves outward and into the public square, we must be prepared for battle. That’s the fourth goal of this book, and the source of the title the publisher and I finally settled on: How the Nations Rage.

Did you pick up on the reference to Psalm 2?

Why do the nations rage

and the peoples plot in vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers take counsel together,

against the LORD and against his Anointed, saying,

“Let us burst their bonds apart

and cast away their cords from us.” (vv. 1–3)

The division and contention of our present cultural moment is just one more illustration of the nations’ rage against the Lord. Division inside the church roots in such rage. The disdain you feel in the media, academy, or courtroom roots in such rage. The arguments on social media depict this rage. Ironically, news sites even know that rage leads to more “clicks.” Rage means advertising dollars.

If the public square is a battleground of gods, the saints should expect the rage of the nations to burn hot in the square. Political philosophers often claim that we can greet one another in the square on religiously neutral terms through what they call a social contract. I will argue in chapter 2 that this is a Trojan horse for idolatry. In fact, every combatant will fight for his or her god’s brand of justice. Every time. All the time. They will even send lions to devour the saints wherever we oppose their gods and their version of justice.

But amid the heat and the lions, every Christian, for love of neighbor, must use whatever political stewardship God has given, even if that stewardship doesn’t include the insider’s access of a Washington, DC, speechwriter like Charles. We should enter the public square as what I will call principled pragmatists.

Here’s an awkward question that the reality of the battle raises: how often do you think Americans think of Psalm 2 when asked about verses on politics in the Bible? More uncomfortably, how often do we locate America in Psalm 2: Yes, one of those raging nations and peoples plotting against the Lord and his Messiah is America.

Or did you think America was exempt from Psalm 2’s indictment? I’ll confess, it’s an idea that makes me uncomfortable. It almost feels like criticizing your home.

Goal 5: Becoming Less American and More Patriotic

I want to help us be less American so that we might be more patriotic. To put it another way, I want to help you and me identify with Christ more so that we might love our fellow citizens more, no matter the name of our nation.

When you become a Christian, your identity dramatically changes, and you gain a new citizenship. Suddenly, the most important thing about you is not your gender, who your parents are, where you are from, how much money you have, what color your skin is, your nationality, your intelligence or beauty, whether you are married, or anything else that humans ordinarily use to identify one another. The most important thing about you is that you are united to Christ through the new covenant and made a citizen of his kingdom.

Who are you, Christian? You are: A new creation. Born again. An adopted heir. A member of Christ’s body. A citizen of the kingdom. A son or daughter of the divine King.

When all this happens, then you find yourself having to renegotiate how you relate to all those old categories. How do you relate to your parents, your colleagues, your friends, your ethnic group, your government, the public at large, even what society says it means to be a “man” or a “woman”?

The Bible calls Christians “aliens” and “strangers” and “sojourners” and “exiles,” depending on your translation. Each of these labels reminds us that this world is not our final home, and that we await another city whose architect and builder is God. The labels resonate with Jesus’ instruction to live in but not of the world. And knowing how to strike both sides of the in-not-of balance is challenging in every area of life, perhaps especially in our relationship to the public square. How do we live as citizens of a nation while being a citizen of the kingdom of Christ?

Step one is letting go of America and our American identity long enough to give it to the Lord and let him fashion it as he pleases. We become better friends to America by loving Christ first. This frees us to be honest and not blind to our national failings. “Faithful are the wounds of a friend; profuse are the kisses of an enemy” (Prov. 27:6).

Step two is remembering that Psalm 2 is not about the power of the nations’ rage, but its futility.

He who sits in the heavens laughs;

the Lord holds them in derision. (v. 4)

The psalm promises the victory and rule of Christ over every nation, military, and government:

Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage,

and the ends of the earth your possession.

You shall break them with a rod of iron

and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.” (vv. 8–9)

We come therefore with the word of the King of kings and Judge of judges, and his word goes out to every nation, including ours:

Now therefore, O kings, be wise;

be warned, O rulers of the earth.

Serve the LORD with fear,

and rejoice with trembling.

Kiss the Son,

lest he be angry, and you perish in the way,

for his wrath is quickly kindled.

Blessed are all who take refuge in him. (vv. 10–12)

As I mentioned earlier in this chapter, a losing team becomes desperate and takes desperate measures. But what might it look like for the church’s politics if we became convinced—really convinced—both that we will have trouble in this world and that Jesus has overcome this world, as he promised? Might we present a strange and winsome confidence that is not desperate to win the culture wars but is also tenderly and courageously committed to the good of others?

The primary goal of this book is not to help Christians make an impact in the public square. It is not to help the world be something. It is to help Christians and churches be something.

My posture in this book is a pastor’s. I want Christ’s people to follow Christ in every area of life, including in their capacity as voters, officeholders, lobbyists, editorial writers, jurists, and citizens.

So this is a book for Christians.

Now, I hope that what follows does equip some readers to make an impact in the public square, and that all readers might know what it means to live peaceful and quiet lives (1 Tim. 2:2). But we need to start with knowing who we are and being true to that identity.

So remember your baptism. Your baptism argues that you have been buried and raised with Christ, and that you should represent his righteousness, justice, and love everywhere you go.

A Christian’s political posture, in a word, must never be withdraw. Nor should it be dominate. It must always be represent, and we must do this when the world loves us and when it despises us. Anyone who tells you, “Withdraw, we’re losing!” or, “Push forward, we’re winning!” may have succumbed to a kind of utopianism, as if we could build heaven on earth. Instead, heaven starts in our assemblies, even if only as in a mirror dimly. Christians are heaven’s ambassadors, and our churches are its embassies. Neither panic nor triumphalism become us. A cheerful confidence does. We represent this heavenly and future kingdom now, whether the skies are cloudy or clear.

CONCLUSION

Indeed, here is the irony we will discover at the end of all our rethinking: the church’s political task is unchanging. Until Christ returns, the nations will rage and plot in vain. We, meanwhile, point to the Lord and to his Anointed, both in word and deed. We’re on the right side of history so long as we stand with the Lord of history. His vindication will be our vindication.

Honestly, you may or may not make a public impact in this life. You may or may not make a difference “out there.” Society may get better; it may get worse, regardless of the activities of faithful Christians. That is outside of your control and mine. What is within our control is whether we seek justice, love our neighbor, and do both these things wisely, not foolishly.

On the Last Day, God will not ask you, “Did you produce change?” but, “Did you faithfully pursue change in those places where I gave you opportunity and authority?”