Governments serve gods. This is true of every government in every place ever since God gave governments to the world. The judge judging, the voter voting, the president presiding, all of them work for their gods. No citizen or officeholder is religiously indifferent or neutral.

Let me explain in two steps. Step one: our religion or worship is bigger than what happens at church. It involves everything we do. To see that, just ask why, why, why.

I’m having oatmeal for breakfast.

Why are you having oatmeal?

To be healthy.

Why do you want to be healthy?

So that I can work hard.

Why do you want to work hard?

So that I can get what I want.

Why do you want to get what you want?

So that I can be happy.

Why do you think that will make you happy?

If you keep asking a person “why,” eventually you will reach a backstop—something with nothing behind it and that doesn’t move. Here you find that person’s gods. Our gods are the backstop or foundation for all our thinking, longing, and acting. Our gods are

whatever we cannot imagine living without,

whatever we most love,

whatever we most trust, rely on, and believe in, and

whatever is our final refuge.

Our gods motivate our big and small decisions alike. This is why the apostle Paul told us to “glorify God in your body” and to do so “whether you eat or drink” (1 Cor. 6:20; 10:31), be it oatmeal or Frosted Mini-Wheats, which I prefer.

One of the top legal philosophers of the latter half of the twentieth century, Ronald Dworkin, made just this point. “Religion,” Dworkin said, “is a deep, distinct, and comprehensive worldview” and “a belief in a [supernatural] god is only one manifestation or consequence of that deeper worldview.” Religion is whatever gives a person’s universe purpose and order. So Dworkin described himself as a religious atheist.1

Non-Christian novelist David Foster Wallace drew out the lesson: everyone worships. He wrote, “In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.”2

You probably noticed that I’m saying gods—plural—not god or God, because our hearts usually contain multitudes. One moment it’s the God of the Bible that we worship. The next moment it’s the god of our parent’s approval. Then the god of fleshly desire. Then the god of cultural acceptance. Then the god of cool. Then the god of our skin color. Then the god of a Super Bowl hero. Then the god of personal ambition. You get the point.

Our hearts are battlegrounds of gods.

So step one for understanding my claim that governments serve gods is seeing that our religion is bigger than what happens at church. Step two is seeing that our politics are bigger than what happens in the public square. In fact, our politics involve everything we do.

Typically, we think of politics as the stuff of congressmen and councilmen, school boards and voting booths. That’s part of politics. But there’s a bigger story. The story of politics is the story of how you and I arrange our days, arrange our relationships, and arrange our neighborhoods and nations to get what we most want—to get what we worship. Every one of us employs whatever power we possess, including the mechanisms of the state, to gain whatever we find most worthy of worship—what we worth-scipe, as the Old English had it.

Just as our natures are religious, being designed to worship, so our natures are political, being designed to establish a social order.

You see this when children play house and offer each other various roles. “You be the kid. I’ll be the mommy.” You hear it in their disputes over whether the ball rolled out of bounds.

Or, had you been present, you would have heard it from the four-year-old son of a lawyer friend of mine. One day at preschool the boy’s teacher asked him to come inside after playtime. The four-year-old, son of a lawyer, replied sincerely, “I will take it under advisement.”

In a fallen world, all of us game the rules and play the people over us in order to slant life’s benefits to our advantage. That’s why, even if you don’t think you are interested in politics, you are deeply interested in politics.

As children, we trade obedience for cookies. As adults, we leverage job choices, marital fights, clothing styles, artistic pursuits, body type, skin color, national identity, gender stereotypes, insider social cues, rolling eyes and sighs, church attendance, automobile brand names, friendships, and more all to shape our little plots of dirt according to our hearts’ desires. Whenever we can grab onto the levers of state power, we do the same. The sword of state is just one more tool for this larger political project of rule and acquisition.

No king or queen rules for rule’s own sake. Every king and queen—insert your name and mine here—rules for a reason. And that reason is our religion, our worship.

Politics serves worship. Governments serve gods.

WARS OF RELIGION

Americans today talk about the culture wars. It might be slightly more accurate to call them wars of religion, because religion is at the root. None of us steps into the public square leaving our objects of worship behind. We take our gods with us. It’s impossible to do otherwise.

Last week I was teaching a class of Christian college students doing internships in Washington, DC. One student asked whether we had the right to impose our morality through law. I said, “Name one law for me that doesn’t impose someone’s morality.”

The class paused. Thought. Then chuckled. “Right, there is no such thing.”

Similarly, a US senator on the Senate Judiciary Committee recently expressed her concern about a Roman Catholic law professor who had been nominated for a circuit court judgeship. The senator explained, “I think whatever a religion is, it has its own dogma . . . And I think in your case, professor, when you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for years in this country” (emphasis added).3 If I could, I would pose the same challenge to the senator that I posed to the college class: Senator, please name one big issue that doesn’t depend on every side’s dogmas. Or one small issue? Senator, do you assume your own dogmas don’t motivate your positions and decisions?

More to the point, behind every Senate Judiciary Committee vote, Supreme Court decision, protestors’ picket line, editorial board meeting, social media campaign, interest group press conference, political action committee e-mail, campaign television advertisement, and presidential veto is someone’s basic worldview of how things ought to be. And behind that worldview is a god. This is true whether the matter up for debate is abortion, same-sex marriage, tax policy, immigration law, or funding for national parks.

Likewise, a nation’s constitution and laws are those places where a consensus exists between our many gods or where one god has defeated the others. They are the terms of victory, the peace treaties, the détentes from decades and centuries of battles. No one god wins all the wars. Rather, a nation’s laws are a collection of competing values and commitments, cobbled together over time by compromise and negotiation.

We can’t help but bring our gods into the public square. Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel did not use the language of different gods—that’s a biblical way of putting it—but he agreed with the basic point. The pro-choice position, he said, “is not really neutral on the underlying moral and theological question.” Instead, it “rests on the assumption” that Christian teaching on this topic “is false.” Both the case for banning abortion and the case for permitting it presuppose “some answer to the underlying moral and religious controversy.” He proceeded to say the same thing about same-sex marriage: “the underlying moral question is unavoidable.”4 Sandel then pointed back to the Lincoln-Douglass debates to make his point. In the 1858 Illinois senate race, Stephen Douglass said he was neutral on slavery. Abraham Lincoln replied that only someone who accepted slavery could say that. Douglass, like everyone else, had a moral position on slavery, and behind that a religious position.

Just as our hearts are battlegrounds of gods, so the public square is a battleground of gods, the turf of our religious wars.

Either we ask the state to play savior, or, to say the same thing a different way, we demand it plays servant to our gods. Sometimes our gods agree with one another; sometimes they don’t. And that’s when the fighting starts in the public square.

What is the public square? It’s all those places where the nation goes to talk, debate, and make decisions that bind the whole public. It’s the letter to the editor, the Parent Teacher Association, the hallways of Congress. A nation’s public square is where a citizenry wages war on behalf of their gods.

There the ambassadors of Jesus and Allah, the representatives of the Christian’s big-G God and the Darwinist’s little-g god, the agents of this party’s idols and that party’s idols, come together to hustle and grapple, joust and cross swords, for the purpose of winning the day and pulling the levers of state power.

So it was in ancient Greece. Think of Socrates, that stout old figure of philosophical lore. He was executed, Plato told us, for “believing in deities of his own invention instead of the gods recognized by the state.”5

So it was in ancient Rome. Caesars and senators like Tacitus accused Christians of atheism and hatred for the human race because they would not pay tribute to Rome’s gods. And the Romans believed the gods’ favor sustained the prosperity of the empire.6

So it was in ancient Israel, who, one prophet would say, had as many gods as it had cities (Jer. 2:28; 11:13).

So it was in the communist revolutions in China and Russia, when Mao and Lenin both thought they could exterminate that worst of political rivals, God.

So it can be among those who adhere to conservativism, liberalism, and nationalism. Conservativism can idolize tradition; liberalism, freedom; nationalism, the nation.

Our gods, whatever they may be, are always present in the struggle for who gets to rule.

The holy battle rages on, even if we deny it. Our gods determine our morality, and they determine our politics—unavoidably. They are not always consistent with one another. They are not always apparent to us. But they are always there, determining our political postures and positions. There is no such thing as a spiritually neutral politics.

Just as China’s Communist Party tried to dispose of God, so did those who protested the Communist Party. “We want neither gods nor emperors,” sang the students as they gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989. They wanted to be their own gods and emperors, of course. In our sin, my children and I sympathize. So do you and your children, if you know your own hearts.

BUT SHOULDN'T WE KEEP POLITICS AND RELIGION SEPARATE?

Of course, talking this way goes against the way Christian and non-Christian Americans alike have been trained to talk and to think.

We learn in school how carefully the Founding Fathers sought to separate government and religion. President and so-called father of the Constitution James Madison said, “An alliance or coalition between Government and religion cannot be too carefully guarded against.”7

While you may hear politicians peppering references to the Almighty into their speeches and even the president closing every State of the Union with “And may God bless America,” the legislatures that make the laws and the judges who review them wouldn’t dare invoke a divine authority. So said Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: “The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky.”8 The Constitution is “the supreme Law of the Land”; it testifies to itself in article 6.2.

We strive to keep politics and religion separate in our churches too. I walk into Sunday school. The teacher explains that the gospel of Jesus Christ is the good word of salvation, not the promise of political change. Later, I open my study Bible and read the study notes on Matthew 5:3, which say that Jesus “is a spiritual deliverer rather than a political one.”9

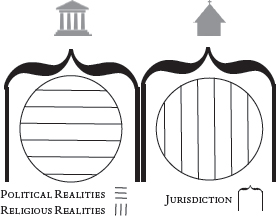

This is how we talk and think. Some people say that politics and religion must be entirely separate. Call them the hard separationists. They would say the institution of the state deals with political stuff, while the institution of the church deals with religious stuff. Like this:

Most Christians think of themselves not as hard separationists, but as soft separationists. They believe that politics and religion should overlap in a few places but mostly remain separate. Like this:

You wouldn’t talk about practicing your religion in the voting booth or the jury’s box. Nor would you say that church services are for engaging in politics. Right?

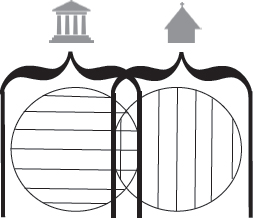

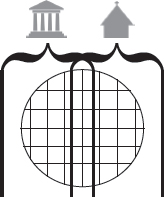

There are sensible historical and theological reasons behind the impulse to separate politics and religion. The emperor and pope once ruled “Christian” Europe together. Like this:

This shared rule of church and state, particularly when combined with a view of church membership that ignored the need for regeneration, helped to create whole nations called Christian that were filled with people who weren’t actually born-of-the-Spirit Christians. The shared rule forced false faith. It killed and tortured people in Jesus’ name. It distracted churches from preaching the gospel.

The Protestant Reformation didn’t immediately solve this problem. In some respects, it temporarily made the arrangement worse. The princes of Germany and kings of England became supreme over everything, including the church. They offered the previous graphic, only they put the state on top. And so Protestant and Catholic sovereigns went to war with each other. Across the Atlantic in the American colonies, one Protestant denomination would suppress another.

Yet something else was unleashed in the Reformation: Martin Luther’s emphasis on the individual conscience, which would eventually yield a doctrine of religious tolerance. By the early 1600s Baptist theologians like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys argued that God does not permit governments to meddle with religion or matters of conscience. By the late 1600s philosophers like John Locke made this point in a more philosophical way. Locke argued that governments should concern themselves with “outward things” such as life, liberty, health, money, lands, houses, and the like. Churches, however, should concern themselves with “inward things” like the care of souls and the mind.10 Governments, therefore, should make room for Protestants and Catholics, Anglicans and Baptists.

A century later, in the 1770s and ’80s, Thomas Jefferson, a fan of John Locke, made the same distinction between the inner and outer person. He then drew the conclusion, “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say that there are twenty Gods, or no God.”11

Around the same time Baptist minister John Leland said something very similar: “Let every man . . . worship according to his own faith, either one God, three Gods, no God, or twenty Gods; and let government protect him in so doing.”12

THE AMERICAN EXPERIMENT

So think about what’s happening here. Enlightenment folk like Jefferson and Protestant folk like Leland might have had slightly different reasons for wanting to separate government and religion—one claiming to rely on reason, the other on revelation—but both parties agreed they should be kept separate. So, at the risk of oversimplifying, they shook hands and made a deal. Today we call that deal the American Experiment.

The American Experiment is the idea that people of many religions can join together and establish a government based on certain shared universal principles. Think of it as a contract with at least five principles. Principle one of this contract is that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed,” says the Declaration of Independence. Principle two is religious freedom. Three is other forms of freedom and equality. Four is the idea of justice as rights. And five is the separation of church and state.

Now, the founders lived in a formally religious society. In many of their writings they appealed to natural law to justify these various principles: God exists, and everyone has a primary responsibility to God for his or her conduct and behavior, and then to the state. The Constitution never invokes these justifications, but those who signed it arguably intended for it to give Christians a favored place in the public square, even while protecting churches from governmental incursions.

Yet here is what’s crucial. Just because two religious people make a contract doesn’t make the contract itself religious. And the founders’ idea of government by consent doesn’t include God in the contract. In fact, the legal terms they set forth in article 6 of the Constitution, forbidding any religious test, made belief in God like a sunroof on a car: an optional extra. A citizen might believe in him or not, but the contract establishing a government is still a contract, just like a car is a car with or without a sunroof.

Likewise, the argument for religious freedom does not depend on believing in a big-G God. After all, how can you require people to believe in God in order to accept the argument that says they are free not to believe in God? From the beginning, therefore, the argument for religious freedom was built on the right to a free conscience. Everyone, whether they believe in a big-G God or not, wants a free conscience.

The same is true for the affirmations of general freedom, equality, and rights. One can offer a theological defense for each of these principles, as the founders and generations of Americans did. But the principles are freestanding, and one need not provide such a defense.

Back to the car analogy: It’s as if the founders designed a car with good drivers in mind, but nothing in the design of the car prevented bad drivers from getting behind the wheel and crashing it. They wanted to keep faith and politics, religion and government, separate. Yet the ironic truth is, we can’t help but drive the car on behalf of our God or gods.

We would be fools to think otherwise.

IDEOLOGICALLY RIGGED METAL DETECTORS AND TROJAN HORSES

What happens when people fool themselves into believing that it’s possible to separate our politics from our religion?

For starters, you create the illusion of a public square that’s religiously neutral, or at least partially neutral. But what you really have is a square rigged against organized religion. Organized religions are kept out. Unnamed idols are let in.

Imagine an airport security metal detector that doesn’t screen for metal but for religion standing at the entrance of the public square. The machine beeps anytime someone walks through it with a supernatural big-G God hiding inside one of their convictions, but it fails to pick up self-manufactured or socially constructed little-g gods. Into this public square the secularist, the materialist, the Darwinist, the consumerist, the elitist, the chauvinist, and, frankly, the fascist can all enter carrying their gods with them like whittled wooden figures in their pockets. Not so for the Christians or Jews or Muslims. Should they enter and make a claim on behalf of their big-G God, the siren will sound like a firetruck. What this means is that the public square is inevitably slanted toward the secularist and materialist. Public conversation is ideologically rigged.

Here’s another illustration. The illusion of separation is like a Trojan horse for idols and nameless gods. Do you remember how the Greek soldiers hid inside a massive wooden horse and left it outside the gates of Troy? The people of Troy pulled the horse inside the city gates. Then, while the city slept, the soldiers snuck out and destroyed the city. In the same way, claiming to separate politics and religion keeps organized religion outside the city gates while hiding idols and unnamed gods inside this very claim.

When we’re not paying attention, even those three hallmark American principles of rights, equality, and freedom become Trojan horses. After all, who gets to decide which rights are right, or how to define equality, or which freedoms are just? Shall we affirm the right to an abortion, marriage equality, and the freedom to define one’s own gender? Well, the answer depends on what your God or gods say. Christians, therefore, find themselves in the peculiar position of wanting to say that rights, equality, and freedom are good God-given gifts, but looking around and seeing people treat those gifts as gods, or at least as Trojan horses that hide their real gods.

For instance, a recent survey of 1,500 undergraduate college students suggested that free speech is “deeply imperiled” on US campuses.13 Is it the case that free speech is imperiled, or is it the case that our society’s sense of what’s morally acceptable speech is quickly shifting between one generation and another? The college students and administrations of, say, 1790, 1840, or 1950 would not have tolerated every conceivable form of speech. Imagine how campus administrators and students would have responded to the prospect of a pro-abortion or pro-gay marriage speaker in 1840. I don’t deny that some nations have broader and some have narrower boundaries for what’s morally permissible speech. But every nation has some boundaries, and those boundaries depend on its prevailing gods. The concept of free speech is a Trojan horse. It’s hiding someone’s gods.

Might we even say the same about religious freedom? Amid America’s quickly shifting moral consensus, it’s tempting for Christians to fall back on religious liberty as a stop-gap measure, at least to protect themselves. But hold on. We’ve defined religious freedom as freedom of conscience, remember? And what if my conscience demands things that your conscience finds abhorrent? Whose conscience wins in court? The very idea of a free conscience begins to look like an empty Trojan horse. People can pack the soldiers of any god they want inside of it.

For example, the 1992 Supreme Court case Planned Parenthood v. Casey said that “men and women of good conscience can disagree” on abortion. Therefore, we should protect a woman’s right to choose an abortion as a way of respecting her conscience. That is, we should protect abortion as a religious freedom. After all, isn’t sexual freedom a religious freedom in a pagan culture? Isn’t it an altar of worship? It was in the ancient world. And pro-choicers do fight for their cause with religious zeal.

In other words, when you define religious freedom apart from the God of Scripture, eventually those terms will be used against the people of that God. Yes, that’s the paradox of religious freedom.

Don’t misunderstand: I will present very Christian reasons to affirm religious tolerance, along with rights, freedom, and equality generally—those American ideals—later in the book. Still we find ourselves in this strange moment of American history where the American arguments for religious freedom just might be destroying religious freedom, and the American arguments for rights and equality just might be destroying rights and equality.

CHRISTIAN LANGUAGE BECOMES IRRATIONAL

So the first result of pretending we can separate politics and religion is that we ideologically tilt the public square floor against our Christian moral heritage and organized religion generally. The second result is that it makes some elements of Christian speech—especially related to the family, sexuality, and religion—sound irrational and therefore unjust.

Think about it like this. You’re sitting at lunch with a non-Christian friend. The question of same-sex marriage or transgender bathrooms comes up. You try to think of some way to say that same-sex marriage is wrong, or that God created people male and female. But you know that stating the matter this plainly will get no traction. In fact, such words might not even make sense to your non-Christian friend. “It’s wrong? What do you mean by ‘wrong’?”

I remember sharing a lively political conversation one afternoon in graduate school with nine of my political science classmates. The year was 1996, and I was the only professing Christian. The first topic of debate was abortion. I alone defended the life of the child. The other nine pushed for a woman’s right to abort her child. Yet the conversation was respectful and courteous because I was able to use language that my classmates recognized and understood: “The baby has its own DNA,” “Biology textbooks will tell you it’s a human life,” “The baby has rights too!” and so forth. They disagreed with me, even strongly. But they respected me because they understood my logic.

Then the conversation switched to the topic of the morality of homosexuality. Once again, I stood alone in making a case against it. But this time the tone of the conversation changed. It was no longer courteous and respectful. My classmates were shocked and offended that anyone would hold such an intolerant view. (And this was 1996!) I remember thinking afterward that the topic of homosexuality was going to prove more divisive and difficult in the so-called culture wars than even abortion had. My views didn’t make sense to their version of rationality or their version of justice.

In the public square, people fear the irrational and become angry toward injustice. Irrationality and injustice are linked because the first often leads to the second. And such fear and anger make sense. You’re wise to fear a powerful force that’s irrational, and you’re morally right to be angry toward injustice. It’s easy, therefore, to size up a nation’s gods by asking where that nation gives moral approval to fear and to anger—even to rage.

My classmates were angry at my views on homosexuality in 1996. They found them both irrational and unjust. And that same fear and anger toward Christian views of the family and sexuality increasingly permeate America’s public square today. To employ such language today sounds irrational and unjust. It evokes rage.

The only moral vocabulary that is permitted in the public square today is the language of rights, equality, and freedom. That language works fine for Christians when everyone shares a basic Christian-ish morality. But it effectively leads to a dishonest conversation when our moralities and religions radically diverge. It hides what’s really at stake, like the senator telling a judicial nominee that her dogma lives loudly within her, as if it doesn’t live loudly within the senator.

In a way, I think the American founders understood all this. George Washington said in his Farewell Address that “true religion and good morals are the only solid foundations of public liberty and happiness.” John Adams similarly observed, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”14 These two founders, in other words, would have given at least some credit to our nation’s success and durability not to democracy or liberal values (liberty, rights, equality), but to “true religion and good morals.” They seemed to understand that the American Experiment is like a gun: how it will be used depends on the morality of the person holding it. Or like a car: much depends on the driver. Or like a Trojan horse: Whose soldiers are hiding inside?

Writers and pastors sometimes say the solution to today’s culture wars is to get back to the American founders. I don’t think we have ever left them. What’s changed is the source of our morality. Whether Christians or not, the generation of the founders shared a Christian-ish morality (apart from the topic of slavery and the inequality of blacks and whites, and the treatment of women). That’s no longer the case.

Our rights might have come from God, but we’ve made them god. We are like rich and spoiled children who have forgotten that all the wealth we possess comes from our parents. And so we squander our wealth foolishly.

SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE

I was speaking on the phone with a friend several weeks ago who was complaining about American evangelicals. Thinking of himself as a separationist, he critically called them “soft theonomists.” Theonomists believe in some combination of church and state, often along the lines of what God ordained in ancient Israel. Theos is the Greek word for God and nomos the word for law. Put them together and you get God-law, which practically becomes church-state, or something like that.

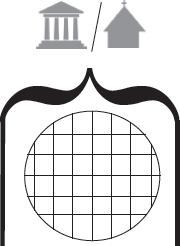

Is that what I’m endorsing? Well, if, by theonomist, you mean I’m going to take some of my religion into the public square, then, yes, because everyone is a theonomist in this fashion, including my friend. No, I won’t take all my religion into the public square. But what I enter the public square with represents my religion. The same is true for everyone. There’s no such thing as separationism in this sense. It’s all a bluff. But if, by theonomist, you mean I’m going to blend church and state, then, no, I’m not advocating theonomy because I’m a staunch supporter of separating these two God-ordained institutions. As I said in chapter 1, we can’t separate religion and politics, but we must separate church and state. The perspective of this book, therefore, is this:

All of life is both political and religious, because we are political and religious creatures. But church and state possess distinct, God-given authorities with distinct jurisdictions. We’ll explore this further in later chapters.

That brings us to a second paradox for this chapter. The first, you may recall, is that the logic of “religious freedom,” if not the language itself, will be used against God’s people in an unvirtuous society. The second is this: nearly every American today affirms the separation of church and state, but that institutional distinction is a Christian one, and it applies uniquely to Christians (and perhaps to members of other organized religions, but I’m going to focus only on churches for now).

Therefore, the separation works splendidly between Christians in churches of different denominations. Don’t make me pay taxes to support your Anglican church, and I’ll respect your freedom to baptize your infants.

Yet the conversation changes when you apply it to a Christian and a non-Christian. The non-Christian, after all, doesn’t have a church. When the non-Christian affirms his belief in the separation of church and state, he means separation of government from my church, not his own. He effectively says, “You can’t impose any of your beliefs and morals on me because they come from your church.” Okay, but does that mean he cannot impose his idolatrous and non-Christian views on me? Ah, there’s the catch. He has no official church and no god with a name. And there’s no such thing as the separation of idolatry and state. Too bad for me. Lucky for him. Do you see what I mean when I say it applies uniquely to the Christian?

Biblically understood, the separation of church and state isn’t about who gets to decide what morals will bind a nation. It’s about the fact that God has given the state one kind of authority and churches another kind. Yet how many non-Christians do you think can define what church authority is, much less care to? How many Christians, in fact, do you think know what church authority is? Yet unless you can explain what the authority of a church is, you cannot explain the separation of church and state. The separation, after all, means the state must not do what God authorized the church to do, and vice-versa. Do you know what he has authorized churches to do? We’ll unpack it later.

For now, we can say that the Christian belief in the church sidetracks us politically. It keeps us from imposing not all but a host of our beliefs on unbelievers—like the belief that Jesus got up from the dead and is the King of kings. Our doctrine of the church says, “Hey, Christian, apply your belief that Jesus is king over there, among your fellow church members.”

Unbelievers don’t have a doctrine of the church that sidetracks them. They impose whatever beliefs and morality they want. People often criticize John Calvin for his argument that the state should enforce the first two commandments (no other gods, no idols), and I would agree with those critiques. Yet it occurs to me that more and more secular progressivists do what Calvin did—they publicly promote their gods and prosecute forms of worship that offend them. My friend Andrew T. Walker recently tweeted:

Don’t be fooled: Secularism is a form of theocracy. It’s very jealous for its own glory, commands our worship, & demands a set of ethics.

How do secular progressives do this? Certainly through the ordinary legislation and judicial processes. Yet it’s also worth highlighting the work that public schools and education policy do in making disciples. Education is a society’s “paramount moral duty,” said political philosopher John Dewey, since it is “the fundamental method of social progress and reform.” Through the public schools the children of a nation come to “share in the social consciousness” of that nation.15

To put it another way, public schools, as agents of the state, participate in the religious indoctrination of their students. Before the Civil War, schools reinforced a Protestant orientation. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, school lessons began to move in a naturalistic direction. After World War II, secular progressivism became increasingly predominant. Schools today especially work to cultivate students who are conscientious in matters of social justice.16

A member of my church whose children attend a Washington, DC, public school recently received an e-mail announcement from the school notifying parents of the school's participation in a Gay Pride parade. I appreciate the fact that the school sent an e-mail. That doesn't always happen now. The letter explained that the school “values diversity” and “strives to create a safe and inclusive environment.” The administration believed that participating in the parade would be “a great way to proactively engage your child(ren) in a conversation about LGBTQ people in a way that focuses on acceptance, respect and understanding, promoting the spread of correct and positive information.”

I, too, hope that schools will foster “acceptance, respect and understanding” for all people, no matter how they identify themselves. Yet my Christian faith does not treat every conceivable identity-construct as morally legitimate. Should we foster “acceptance, respect and understanding” for those who identify themselves as thieves, adulterers, or (as I saw on one courtroom television show) vampires? For the people themselves, yes. For their identities as thieves, adulterers, or vampires? Not according to my faith.

What this school e-mail represents, then, is the state’s concerted effort to religiously indoctrinate my friend’s ten-, eight-, and five-year-olds in a different faith. A faith that worships the gods of self-definition and self-expression.

Through the classroom, the legislator, and the courtroom, today’s secular progressive is only too happy to use the state to enforce his moral and religious codes. Why wouldn’t he? There is no big-G God telling him to do otherwise. So his little-g gods and priests walk unnoticed into the legislative chamber, courtroom, and classroom. My doctrine of the church, however, keeps me from trying to impose everything the Bible says about sexuality on every American through the public-school system.

Again, in today’s thinking, the separation of the church applies only to those who believe in an organized church. Hence, the separation of church and state politically rigs the system against Christians, at least in a certain kind of society.

AMERICANS AS RELIGIOUS AS EVER

There is no doubt about it: Americans today remain as religious as ever. I don’t mean they identify as Methodists, Mormons, or Muslims. I mean they worship something. And that worship shows up in their politics.

Mary Eberstadt, in her book It’s Dangerous to Believe, said that “a new body of belief” and “orthodoxy” has replaced the Judeo-Christianity of yesteryear. “Its fundamental faith is that of the sexual revolution,” she said. The starting point of this new secular faith is that “freedom may be defined as self-will.” The second principle is that “pleasure is the greatest good.” According to this new religion, the sexual morality of biblical Christianity represents “unjust repression.” Yesterday’s sinners have become today’s saints, she observed, and yesterday’s sins have become today’s “virtues” and “positive expressions of freedom.”

The first commandment of this faith is that “no sexual act between consenting adults is wrong—possibly except in cases of adultery.” Therefore “whatever contributes to consenting sexual acts is an absolute good, and that anything interfering, or threatening to interfere, with them is ipso facto wrong.” She also asked the reader to observe the absolutist character of this new religion. Contraception and abortion are treated as “sacrosanct and nonnegotiable.” It won’t even draw the line at the horrifying procedure of partial-birth abortion. Instead, she said, “abortion within this new faith has the status of religious ritual. It is sacrosanct. It is a communal rite.”

It’s not the heresies of the past like Pelagianism and Arianism that are a threat to Christianity, she observed. The single biggest religious challenger to Christianity in the contemporary West is “sex.” In a chapter entitled “Anatomy of a Secularist Witch Hunt,” she explained:

After all, Christians and other dissidents aren’t threatened with job loss because of writing in self-published books [as the Atlanta fire chief was] about the biblical teaching against stealing, say. Military chaplains are not being removed from office and sidelined for quoting from the book of Ruth. No, every act committed in the name of this new intolerance has a single, common denominator, which is the protection of the . . . sexual revolution at all costs.

She then concluded the point: “Secularist progressivism today is less a political movement than a church.” And the so-called culture war does not pit people with religious faith on one side and people of no faith on the other side. “It is instead a contest of competing faiths.”17

The only qualification I would add to Eberstadt’s remarks is this: the heartbeat of this faith is not finally sex, it is self. The Enlightenment philosophies of Locke and Jefferson began with the self. The American Experiment, wonderful in so many ways, particularly among a virtuous people, ultimately exalts the self. The sexual revolution may have been the inevitable outgrowth of the Enlightenment’s exaltation of self all along. God gave us sex to give us the faintest whiff of what our union with him will be. Whenever humanity replaces God with itself, therefore, we often create houses of worship around that very gift. So it was among shrine prostitutes of the ancient world and among goddesses like Aphrodite. So it is today among a nation that worships its Hollywood heroines and Internet pornography.

CONCLUSION

Later in the book we’ll return to most of the themes raised here and try to get more practical. My purpose for now is to help you see the landscape a little differently—to give you a slightly different map than the one many Americans use.

So let’s return to where we began the chapter: governments serve their gods. It will be one god or another. Our politics and our worship are not as divided as we think. Both involve bowing. Both involve saying who is worthy to rule and to judge.

The citizens of the ancient world commonly regarded a king as either a god (as in Egypt) or a unique representative of a god (as in Babylon). Again and again God therefore tells his people not to put their trust in their own king or in foreign kings. And he tells foreign kings not to put their trust in their gods. Our trust always shows who our gods are.

Which is to say, our politics reveals our worship. It did then. It does now.

Our entire lives are fundamentally political because our entire lives are measured in relation to King Jesus and his claim on our whole person. This is true for Christians and non-Christians. We live in either submission or rebellion. The mechanisms of the state are merely one tool we use in this larger political contest.

The non-Christian nations do not trust God. Therefore, they rage against him and his Son. That is why the public square is a battleground of gods. It may be the case that this battlefield hosts multiple gods pitted against multiple gods. Yet the fundamental battle pits all the gods against the God. They rage against him.

Becoming a Christian, however, means we change our worship and our politics. We submit to King Jesus in all things. We acknowledge that he is praiseworthy and worthy to rule all things. Our politics and worship unite around him.

He creates a whole new politics for us, a political rebirth, a political new creation. We turn to this next.