Prendick may be the narrator and the main character in terms of presentation and point of view, but there are many protagonists in The Island of Doctor Moreau, for which the human characters (i.e., Homo sapiens) are foils. Look at the story again, this time with different points of view creating different through lines, and you’ll see complete personal arcs, full of insights, decisions, and committed actions, for four of the Beast People.

•The Leopard Man, in Chapters 9 through 16 of the novel, relative to Prendick, discussed in this chapter

•The Puma Woman, in Chapters 3 through 17, relative to Moreau, discussed in this chapter

•M’Ling, in Chapters 3 through 18, relative to Montgomery, discussed in Chapters 7 and 9 of this volume

•The Hyena-Swine, in Chapters 16 through 21, relative to Prendick, discussed in Chapters 8 and 9 of this volume.

Processing these personal stories is complex: they’re filtered through Prendick’s narration, and his ideas change several times, always in relation to Moreau’s unchanging view. To get into these stories, these more explicit perspectives need to be explained, prior to parting them like curtains.

Moreau’s point of view is straightforward, unswerving, and incorrect in one crucial point, which serves well as the baseline view of the Man/Beast divide against which Prendick’s changes can be compared.

Again, cast aside the “don’t meddle” story, which has it all wrong. Moreau isn’t trying to be God—he is appreciating God by investigating and extending his works, the perfect nineteenth-century scientist with one foot in the Romantics. He reveres “man” as the primary work of God, and therefore the obvious and imperative aim of such investigation. Moreau’s problem is that his vision of such a work is already idealized entirely out of the ballpark of being human.

In fact, I’ll name his goal, not the ordinary descriptive label “man,” but the exalted, exceptional status of “Man.” This construct is perfectly rational, spiritually elevated, beautiful to behold, master of the world, emotionally serene, and civil in every way, Spencer’s ideal to the letter. Moreau’s uncritical and arrogant view of this entity not only permits his own inadvertent sadism, but blinds him to the results before his eyes: that his creations suffer, believe, sin, and struggle to the same extent that real people do. Moreau’s consuming passion is to overcome precisely this outcome.

For all the clarity and consistency in the rest of his argument in Chapter 14, he is oblivious to his single, outrageous self-contradiction when Prendick asks him why he chose the human form as an experimental goal. His slick “by chance” answer is completely incompatible with every other description by him of that particular goal, throughout the rest of that conversation as well as elsewhere in the story. He really wants to make, not only a person, not only a human, but Man out of entirely nonhuman material. He’s not even trying to create a new kind of “perfect man,” because to him, Man as is, the Creator’s work, is already perfect. Making a real one would be enough—but it must be according to the exceptionalist expectation, not “animal” at all:

. . . just after I make them, they seem to be indisputable human beings. It’s afterwards as I observe them that the persuasion fades. [. . .]

[T]his time I will burn out all the animal, this time I will make a rational creature of my own. (The Island of Doctor Moreau, p. 59)

This is the core of the plot: Moreau succeeds with his procedures. But he cannot possibly see this, because this Man, as he conceives it and which he tries to create, does not exist. He does not see what he has achieved, because he never sees anything but the absence of the rational man. He throws his subjects out into the night, saying, “Bah, failure,” and has little further to do with them. But what they do out there, on their own, is to act like and indeed to experience life as people do.

He complains about them bitterly:

The intelligence is often oddly low, with unaccountable blank ends, unexpected gaps. And least satisfactory of all is something that I cannot touch, somewhere—I cannot determine where—in the seat of emotions. Cravings, instincts, desires that harm humanity, a strange hidden reservoir to burst suddenly and inundate the whole of the being with anger, hate, or fear. (Ibid., p. 58)

Once he gets going on his obsession, his pretended indifference to seeking the human form sloughs away:

I can see through it all, see into their very souls, and see there nothing but the souls of beasts, beasts that perish—anger and the lusts to live and gratify themselves. [. . .] There is a kind of upward striving in them, part vanity, part waste sexual emotion, part waste curiosity. It only mocks me. . . . (Ibid., p. 59)

Aw, poor Moreau. He keeps trying to get a Man, but (damn it!) keeps winding up with boring, grubby, feeling, variably articulate, unfortunate people.

I ask that you reflect upon this for a moment. Moreau is a maniac in the technical sense, rather than the Hollywood sense, arguably psychopathic in that same technical sense, and all too willing to inflict agony—because of his unshakeable mainstream perspective. He’s crazy not because of his scientific techniques, but because he agrees with the Man/Beast divide—his one central and bonkers notion perfectly represents what most people think!

The films consistently and accurately define the Moreau character as committed to the Man/Beast divide, rather than questioning it. This is probably best conveyed, if unsubtly, in the 1977 The Island of Doctor Moreau, when Moreau flips his lid and starts whipping the poor Bear Man for evincing even a bit of his origins, as he’s clearly unhinged at the sight of any combination across the divide.

However, modifying his view so that he seeks to improve upon humanity through his work, as he states outright in several of the films, is a dodge to keep the topic of real people out of the discussion. The line in the 1996 film that claims his creations are “ … a divine creature that is pure, harmonious, absolutely incapable of any malice” is difficult to interpret because it sits on the boundary between conceiving of real people as perfect rational beings, and seeking to create such a being because real people are not.

The films also struggle with how this essential quirk of Moreau’s relates to religion, or more accurately, to God. The common nineteenth-century view that the Creator made a world that operates by laws accessible to science fell out of fashion sometime in the early twentieth century and is not well articulated or commonly recognized today. Therefore the films—which draw upon the strong scientist-as-blasphemer template anyway—either make Moreau a hyper-intellectual whose science defies God and nature, or effectively a cult leader, whether cynical or naïve, whose science is merely a means of creating a subject population toward that end.

If Moreau seems thickheaded about his notions of Man, he is at least in good company, which is to say, nearly everyone else, both in his time and ours. His unchanging view perfectly expresses contemporary Angel/Ape thinking.

These juxtaposed terms “Angel” and “Ape” refer to specific Victorian values and view of humanity, the idea that the human experience is a battleground of two absolutely opposed influences. The first is a veritable army of violent, irrational urges that arise easily and swiftly, bypassing all thought. Sex! Anger! Bad manners! Think of a host of evil spirits or an inherent legacy of sin that infects the mind, then give it a scientific face and gloss by recasting it as vestigial traces of the wicked brutes from which we, humanity, have barely emerged. Meanwhile, the opposition engages in a holding action by progressive, productive endeavors, distilling a perfect social order from human history, all to be instilled in an obstreperous populace only with great effort of some kind (military force, parenting, civil education, take your pick). In this construction, civilized culture is completely and uniquely an add-on to the human animal, rendering it not an animal—bonus points for tagging your own culture as especially accomplished in this regard.

Conceiving the human mind, or “psyche” to use the contemporary term, as such a battleground feels good. It is exactly the same exceptionalism in both social-reformer fervor and ostensibly secular (but not really) military-imperial enthusiasm, with religious language added for either, or not—frankly, that particular language doesn’t matter because the construct and the ideal are the same. My eyes fall upon a different, less trivial language:

•Beastly, bestial, savage, uncivilized, primitive

•Sometimes, emotion or passion, when constructed as uncontrollable

•Human, humane, humanitarian, civil, advanced

•Sometimes, reason, especially when linguistically elevated to the term “rational,” allowing for passion only when it’s directed toward a worthy goal or cherry-picked to be selfless or radiant in some way.

The same things get renamed in various contexts: nature versus nurture, nature/biology versus culture, deterministic versus choice, genes versus environment, instinct versus learning—always opposed, always the same Manichean battleground. Even switching sides to romanticize the Ape as spontaneous, natural, sincere, or authentic doesn’t change the overall construct.1

I don’t advise questioning this construct outside an organized discussion, based on long experience. The nineteenth-century obsession with model of humanity as synonymous with policy position is still very much with us, and the Angel/Ape model is the bed from which most of our modern political views have sprung—to question it is too easily perceived as a direct attack upon one’s own views, or as sneaky support for the worst view the person can imagine.

I can hear it now: “But, but we are smart!” This is one of the arrows in the exceptionalist quiver: an appeal to functionality as an obvious hard-line separation between this constructed Man and Beast. It’s even exactly what Huxley told his audiences in his 1860 “Lecture to the Working Man,” specifically referencing speech as the key variable between the two, thirty-three years before he’d present the rather different view in Evolution and Ethics. I have bad news for you, though: no, we aren’t. We’re pretty good at some neat cognitive actions, but it doesn’t make us smart in any qualitative sense, nor are those actions all that different from what most or all other creatures already do. And we’re really bad at a lot of mental stuff that this or that other creature can do well.

There is no body-mind divide in biology; the concept carries no weight whatsoever. This is right out of Lawrence’s lectures, that thinking is an operation, a physiological act that we exhibit. Like any other physiological undertaking, thinking has parameters of competence; and even within those parameters, it may work or not work, it may produce or not produce, and it may succeed or not succeed, relative to any criterion you like.

The terms “sentience” and “sapience” are not observed in the vocabulary of any scientific discipline. Biologists, especially, do not use them because they apply to every organism you ever heard of. All living things continually perceive their environments and adjust their behaviors in response. These perceptions and adjustments all have parameters and extents according to the species in question, but the underlying point is that there are no such things as an insensible or a moronically robotic living creature.

For instance, do plants think? The simple answer is yes. More helpful is to consider what “thinking” means: whether it’s the means by which we behave, in our case, nerves and brains, or the outcome of behaving regardless of particular physiology, which is to say, responsively and strategically. In outcome terms, plants definitely think, but since it’s practically impossible to use that word without the vertebrate-centric brain-oriented implication or the human-centric verbally oriented implication, I have to qualify it—with a full dose each of Captain Obvious and So What—by adding that plants’ experience of their own behavior is certainly different from ours.

To focus on those outcomes, the real question is, what do real creatures think about? In that context, behavior comes in effectively two forms, staying alive (maintenance) and making new creatures (reproduction). Both can be quite indirect and sophisticated, with lots of subsidiary and derived properties, even including reversals, but details and add-ons aside, a living creature’s life transfers stored energy into radiant heat, and when you look at how, maintenance or reproduction is typically what’s happening. Here’s the thing, though: since a packet of stored energy is used and lost only once, the creature has to trade off its limited stores between the two general categories, as well as among many options within each, including options like “no” and “not this time” in many cases. Life for every creature, no matter how simple, is a nonstop series of literal decisions among viable options. Yes, bacteria too. Everybody.

That line of thought is scientifically powerful, but it is so abstract and divorced from our personal experience—thoughts, identity, emotions, motivations—that it’s hard to apply, and the discussion typically shifts quickly from “what about” to “how.” In that case, we have to bring it all closer to home and talk about animals, with nerves and in many cases brains. Here’s the question of whether we are functionally special, which in fact was investigated startlingly well, practically in isolation and without really good follow-up for a century, by none other than Charles Darwin. It might surprise you to learn that evolution was not really his primary topic of study, but rather nonhuman reasoning and emotions. He might qualify as the single unequivocal non-exceptionalist thinker of that era. However, this work was not well appreciated during his life, nor for about a century afterward.

Past the middle of the twentieth century, the study of behavior remained outside biology as such, conducted primarily in branches of psychology, such as the comparative school founded by Frank Beach and its splinter school of psychonomics, the behaviorist school made famous by B. F. Skinner, the ethological school best known in the work of Konrad Lorenz, and the too-often missed developmental school of Theodore Schneirla and Daniel Lehrman. Other branches include the famous anthropological work with gorillas by Jane Goodall and Diane Fossey. A lot of this work became overrated and a lot of it was unfairly passed over. The disciplinary boundaries and inter-school barriers were very strong, so that most of it remained isolated from formal biology, and much of it did not even get cross-referenced from subdiscipline to subdiscipline. It took a long time for experimental research to focus on problems that made sense to the organisms. Studies of rat behavior didn’t start using semi-natural enclosures until the 1970s, for instance.

Academic integration and a certain intellectual housecleaning emerged by about 1980, including the new designations of behavioral ecology, cognitive psychology, psychobiology, and behavioral neuroscience, as well as refining and effectively resolving the long-standing debate about behaviorism. Behavioral work began to connect with biological and evolutionary researchers, at first in informal academic crossover, then in interdisciplinary groups, and finally, today, many scientists include it in biology along with physiology, systematics, ecology, genetics, and cell studies.

It’s rude but accurate (and funny) to criticize the historical study of mental operations as a bit schizophrenic, with, as the quip goes, the mind studies being brainless and the brain studies being mindless.2 However, a lot of the classical work does stand up, including Darwin’s, and the modern integration is very, very good. One thing is blatantly clear: there is no Beast process or part of the brain-and-mind that is opposed to some Man process or part, not anatomically, not physiologically, and not behaviorally.

Many brain-and-mind operations are quantitative and organizational, or in plain language, based on counting and comparisons. How much quantity, how much distance, how much time, how much difference, how many repetitions, in what combinations—creatures are all really good at processing this kind of information and basing decisions on it, although quite strictly within specific limits, or if you will, priorities. In the animal, neurological context, this precise kind of perception and processing is called cognition.

Studies of cognition are unequivocal: it’s long past time to drop the model of humans with mystic capacities to do ordinary things and of nonhumans as insensate automata, switching back and forth between these portraits whenever considering real observations about the other.

Here’s a key point: most behaviors tagged as reflexive are no such thing. The physiological response called a reflex has been quite wrongly applied to behaviors that are simply fast and nonverbal, but rely on as much cerebral processing as the most complicated thing you can think of. Just because you did something “without thinking” doesn’t mean it was a technical reflex, as observed in the compromised nerve of your knee. It was thinking all right—it simply wasn’t talking, and we tend to ascribe too much power to that activity. This same error has also been confounded with “instinctive,” unfortunately, with a whole raft of further associations folded in, so that humans’ behavior can be falsely walled away from instinct, and nonhumans’ behavior can be falsely tagged as unthinking no matter how complex. As I see it, the discipline best labeled “behavior” is close to tossing out all reflexive/processed, instinct/learned, and involuntary/voluntary distinctions, as in their current general constructions, they reinforce the false image of nonhuman living creatures as mindless robots and of behaviors as snap-in modules.

Also, again to varying degrees per creature, perceptions are stored and constantly cross-referenced with both new perceptions and with other stored perceptions from the past, for which “memory” is an insufficient word. This is a significant, consequential operation, but it is neither independent of brain function nor limited to our own species. One of its effects is literally an environmental context for many details of behavioral development. Another is to generate an inner, imagined world, or “constructed” if you prefer, as vivid and important to the creature as the outer, real one, and—from the inside—not easily distinguished from it. Biologists and experimental psychologists call this the cognitive map.

We have no idea what other species’ literal experience of their cognitive maps are like, whether they “imagine” in the same way we do. For ourselves, I stress that the word “imagine” is a bit misleading because I’m talking about more than that—I’m talking about when you walk into a lamppost or other stationary object on a street you’re perfectly familiar with. It’s because you weren’t consulting your immediate sense analysis, you were consulting your cognitive map.

I’ll focus on one well-defined social subset of perception and cognition: communication, in which an individual perceives the signals of another and acknowledges this receipt to the sender. (Its definition is quite careful to distinguish communication from, for example, merely noticing what another creature is doing.) In a highly social species, individuals constantly “swim” in communicated information from other members of the group and live in that “sea” as much as they do in the plain-and-simple physical world. Our own combination of immediate input, memory in this broad sense, and communicated content composes our experience of life, and may be thought of as the medium for our behavior. The position of oneself as an individual in this map is a completely functioning variable, too. From inside, we dress it up as “consciousness,” “awareness,” “imagination,” and “being smart”—and in pure exceptionalist glory, claim it for ourselves all the way from the ground up as a unique feature. I have no beef with the idea that our exact version of it is species-specific, but denying similar, specific versions for other social species is simply to deny the entire body of evidence. Creatures cognitively compare multiple possibilities, assess immediate conditions in the context of past experiences, imagine multiple outcomes, and judge distances in time, amounts, space, and social relationships. Call this “being aware” if you want, but don’t pretend it’s a unique human capacity.

When you put the brain into the study of the mind, and the mind into the study of the brain, remarkable work can be done. Here are just a few of the studies from the past few years, taken from a high-powered series of biology journals called Trends:3

•Regions of the cerebral cortex

•Two-dimensional, or area-based zones of activity set limits on attention, recognition, and memory, but in the long run, the borders shift in what appears to be a competitive manner.

•Two different sorts of self-activity are identifiable, an active agent (“I) and a reflective or perhaps narrative product (“me”).

•Cell functions within the cortex

•Neural impulses among specialized pyramidal cells travel outward through the layers of the cortex and then inward again, regulated by tiny, local inhibitory processes called microcircuits.

•A particular receptor type (kainate-type glutamate) has diverse and complex effects at the juncture of cortical cells, regulating their excitability.

•Microglial cells eliminate and generate the synaptic connections among cerebral cortex cells all the time, such that the neural circuits are constantly changing (plasticity).

•This remodeling goes on all the time in both the cortex and the hippocampus, in response to particular kinds of stimulation, as a feature of ordinary behavior.

•The hippocampus is the site for temporal processing: memory, time and spatial orientation, and prediction.

•Whole neuronal ensembles manage how we remember order and sequences, but single time cells and place cells encode the moments and locations.

•Forgetting things arises from a built-in decay process (efficient pattern separation), but difficulties with encoding and retrieving memories in the moment result from interference—in other words, “forgetting” is a lot of different things.

•And taking comparative work to its arguable and fascinating extreme

•Bacterial mats operate as weirdly coordinated, arguably behaving entities using processes not too different from coordinated neurons.

Finally, certain questions can be addressed and certain myths or intellectual dodges squashed for good. Take “human awareness”—how does a dog go through a door? It does not blunder at a doorway and repeatedly attempt a series of head-butts until somehow it makes it. Why not acknowledge that the dog looked at the door, knew what it was, and went through it? Or more generally, it had some reason to go over there, remembered the layout of the building perfectly well, and knew that getting through the door was the way to go? Conversely, how does a human go through the door? Does the process involve the most edge-case, sophisticated analyses of which the human mind is capable? Do we work out geometric angles, spatiotemporal relations, the engineering of the door, and all the math of reality, using a widget perhaps, to figure it out first? No—like it or not, we go through doors pretty much the same way a dog does.

Similarly, “consciousness” as a human-referenced feature is long overdue for an unsympathetic review. Nonhuman critters can count, remember, assess, and for lack of a better word, judge the circumstances they find themselves in. Each type differs from the others in its parameters (limits, boundaries, points of focus) and in its details of individual experience, including humans. Given all that, what is left for a human-only definition of consciousness? Maybe something, but we won’t figure out what it is until people stop using the term to talk about the soul with its serial numbers scraped off.

If you hold consciousness and awareness to measurable and rigorous variables, which is to say, real things, then humans have no special claim to them, and if you insist that humans have a special claim to them, then they turn out not to be real things. In my experience, people squirm when pinned down on these points, as they objectify nonhuman abilities into a grunting parody of their observed capacity, or move the goalpost of consciousness well past anything we ourselves exhibit. Because nonhumans may not think what we think or share it with us, it is all too easy to say they cannot think, or more generally, that they exhibit no cognition and that their behavior is muddy and halting, or a finely tooled automatic mechanism, anything but messy and processed thought.

It’s also time to stop dodging further down the line of argument by conceding that the operations are the same in kind but insisting without justification that we do them better. We don’t know if our physiological neural sophistication means anything about making better decisions, by any criterion, such as being right at basic problems more often, or handling more sophisticated problems in any way more successfully than basic ones. People talk themselves into this kind of claim by holding nonhumans to abstract and weird standards of “awareness” that neither we nor they can reach, and by invoking “instinct” in the sense of a colorful animal trick when a nonhuman does something smart.4

The word “intelligence” is so often nothing but a marker for these blind spots and refusals to engage with the question. Yes, we think and talk about doing things, to the point of obsessive chatter, and we assign social status based on personal facility with the local cultural idiom. Yet nothing ever studied physiologically or psychologically indicates that we make ordinary decisions more successfully than any creature doing any damn thing.

The same goes for emotions: nothing about the human brain and mind indicates that our intensity or complexity of feelings is anything distinctive. When pressed, the discussion dodges to the undefined term “depth” in order to maintain the exceptional human status.

Other compartmentalization tricks include focusing on conditions outside a nonhuman’s processing parameters while pretending that such limits do not exist for us, and for things that are inside those parameters, cherry-picking nonhuman individual failures and human individual successes. However, all living functionality entails risk, as it occurs in real space and real time, riddled with conditions of failure. It’s easy to forget that our “magnificent rational capacity” or nonhumans’ “perfectly adapted instincts” spend most of their time making mistakes. Pertaining to this, the novel twice features a minor but significant phrase, first at the end of Chapter 13, when the Beast Folk see Prendick surrender to Moreau’s and Montgomery’s pleas to return to the compound, and later in Chapter 19, as Montgomery struggles to make sense of his life just before he dies.

They may once have been animals. But I never before saw an animal trying to think.

[and]

“Sorry,” he said presently, with an effort. He seemed trying to think. “The last,” he murmured, “the last of this silly universe. What a mess—” (The Island of Doctor Moreau, p. 87)

Although these are Prendick’s words, they express his overlap with Moreau’s construct of Man/Beast thinking and intelligence. They both fail to realize that “trying to think” is the best possible description of cognitive processes as we see them in any creature.

Unlike Moreau and Montgomery, Prendick’s understanding, perception, and judgments of the Beast Folk change during the story, several times in fact. But these changes are not from pure confusion to pure clarity, nor from pure vilification to pure acceptance—each phase is a mixed bag, as indicated by the language Prendick uses toward them.

•Chapters 3–6: He thinks they’re people and is disturbed by them, but cannot tell why.

•“[B]rown men,” “black-faced man,” and M’Ling and the “evil-looking” others get the personal pronoun “he.”

•Chapters 7–13: He thinks they’re people mutilated by surgery and is afraid to meet similar treatment.

•The Thing, for the Leopard Man; man, Ape Man; thing, creature, Beast Folk (once), Beast Men, both “he” and “it” as personal pronouns

•Chapters 14–16: He knows they’re nonhuman animals altered by surgery; he becomes increasingly more empathetic, culminating in brief but full acceptance of their humanity.

•The Beast Folk, the brute(s), the animals, strange creatures, grotesques, the Beast People, “your brutes,” “your monsters,” and the appended “Man” and “Woman” to various types; “it” for many, including the Hyena-Swine; the Leopard Man is variously “he” and “it, and similarly, M’Ling is “it” but also “the black-faced man.”

•In Chapter 14, Moreau uses “her” referring to the puma, previously “it” throughout Prendick’s narration, or in Moreau’s comment upon her arrival, the “new stuff.”

•Chapters 17–21: He knows they’re nonhuman animals altered by surgery; he hates and fears them, culminating in full paranoia and murderous intent.

•Generally, “creatures,” “Beast People” (or Folk or Men), “brutes,” with brute as the most common individual term

•The transformed puma is variously “the monster,” “the brute,” “she,” “her,” and “it.”

•The Dog Man and the Hyena-Swine get the pronoun “he” in Chapter 20.

•Chapter 21 only: Beast Monsters, with the Dog Man as “he” and the Hyena-Swine as “the monster” and “it.”

The important phase is the third, when he knows the Beast Folk’s origin but comes to sympathize with them more and more, even briefly to identify with them, or vice versa. This isn’t what happens in most horror stories about human-like monsters, especially in groups. Let’s make one up for purposes of contrast. In it, our hero, Bob, is confronted by stalking, scary humanoids—perhaps they seem like zombies, and in fact, they are zombies, actually dead, yet moving about and craving the flesh of the living. Bob doesn’t realize at first that his pursuers are undead. If our story had the same number of chapters and structure as The Island of Doctor Moreau, then through Chapter 6, he’d think they were crazy humans, and then in Chapters 7 through 13, he’d think they were living people who were altered in some way. Throughout these chapters he might find them scary and upsetting, but still maintain some sense of sympathy for their plight. But then, in the transition between Chapters 13 and 14, he’d correctly learn that they’re classic Hollywood undead.

Well, that does it. Bob goes into full ruthless mode for the rest of the story, shooting the zombies in the head (and similar actions) in order to keep from being eaten, and I think you know how the story goes from there.

In this story, the plot includes a single, perfectly symmetrical flip between Bob’s knowledge and his empathy: as soon as he shifts from fully mistaken to fully informed, his initial sympathy disappears. He might conceivably retain a certain grief or smidgeon of personal horror after that, but not enough to affect his trigger finger; in fact, those secondary characters who do let their empathy interfere with their ruthlessness would be depicted as fatally naïve.

However, in the novel, Bob’s story isn’t what Prendick goes through at all. The transition from mistaken interpretation to complete knowledge is the same, shifting between Chapters 13 and 14. Also, his initial empathy levels are similar in the first two phases as well: disturbed and then horrified regarding what he thinks are distorted human beings. However, when his knowledge flips to the accurate understanding that their origins are fully nonhuman, his empathy levels go through two extreme transitions that map very differently to the knowledge transition.

Since Prendick’s emotional through line in the story does not hinge strictly upon his knowledge of the Beast Folks’ nonhuman origins, it cannot be simplistically slotted into good versus bad categories defined by a man versus beast divide. During Chapters 14 through 16, after he knows what the Beast Folk are, he steadily feels more and more positively toward them. His response begins mainly as sympathy for tortured animals, but then acquires genuine empathy, which peaks during the events of the hunt for the Leopard Man at the end of Chapter 16. At that point, he acts upon and articulates the most uncompromising and least sentimental embrace of nonhumans as fellow beings in literature.

But right at the beginning of Chapter 17, after the mostly undescribed six-week gap in his account, this feeling is entirely gone. Prendick has apparently flatly reversed his perceptions and insights of Chapter 16. He even displays a new distaste and loathing for the Beast Folk, more extreme than his initial disturbance upon originally meeting them. Right at the opening of the chapter, he describes the Beast Folk as “horrible caricatures” of real people, and describes real people as assuming “idyllic beauty and virtue in my memory.”

The textual transition is so abrupt and extreme that it comes off as uncharitable of him, and it instantly begs the question of how his shift in judgment developed during the undescribed six weeks of his stay upon the island. However it happened, it’s permanent; he never again expresses sentiments like those which closed Chapter 16. Instead, his distaste continues and becomes more intense, in a complex process intertwining religion and the Beast Folks’ reversion.

This profile of understanding and judgments captures the two core questions of the plot:

1.Why does Prendick come to feel so deeply in favor of the Beast Folk’s humanity after he learns what they are?

2.Given his deep empathy for them at the end of Chapter 16, why does he come to hate and fear them so dramatically by the start of Chapter 17?

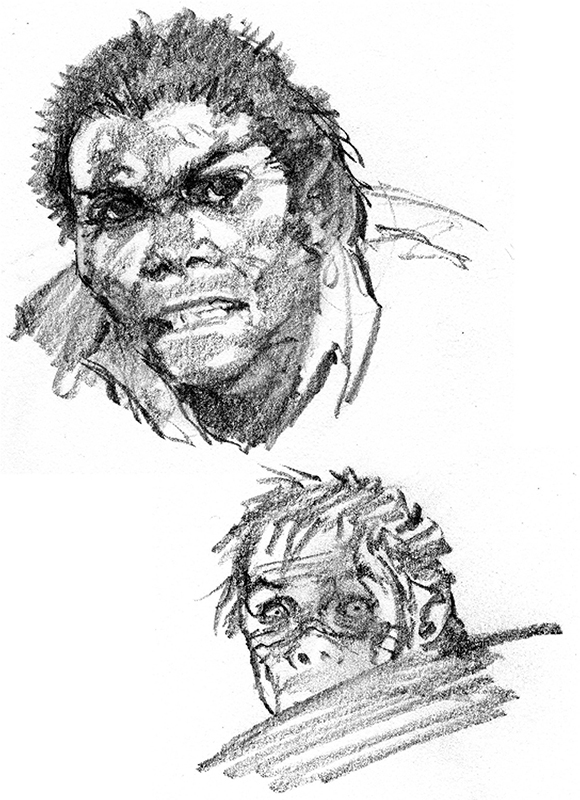

The moment when Prendick’s assessment of the Beast Folk hits its most positive, most sympathetic level is wrapped around the subplot of the Leopard Man, culminating in Prendick killing him. It begins in Chapter 9 with the two as antagonists, just before the Leopard Man stalks Prendick through the forest, probably barely suppressing the urge to take him down as prey.

It’s a dark, mysterious scene, reflecting Prendick’s complete confusion. I’m not sure what the Leopard Man means by saying, “No!” when they come face to face—is it a preemptive refusal of whatever Prendick may order? Is it in defiance of his conditioning, therefore an expression of his desire to kill? Or is it an instruction to himself, to reinforce his understanding that he should not kill prey? It’s like a human’s behavior, but the reader can’t be sure if it is.

I think the mystery arises because the Beast Folk experience complex emotions although their creators do not see it, or they don’t admit what they do see. For example, Montgomery unwittingly reveals quite a bit when he states that he and Moreau must prove (emphasis in text) to the Beast Folk that the Leopard Man killed the rabbit, in order to punish him. Moreau confirms this necessity soon afterward. In other words, the Beast Folk possess a perfectly sound concept of evidence-based jurisprudence and are capable of critiquing the claims of authority, not only individually, but collectively. Moreau and Montgomery cannot simply invoke the Law and crack the whip. Although they both know this and casually refer to it, they don’t notice that they know.

Prendick is not sympathetic toward the Leopard Man, to say the least, and in Chapter 16 he joins in his exposure and in the ensuing chase with a will. Wells clearly did his share of running around in rough terrain; I have, too, and I can confirm that the extended chase sequence perfectly captures the changing ground, the painful and inconvenient struggles through the underbrush, and the lightheaded combination of enthusiasm and exhaustion. In such moments, emotions appear suddenly in a sharp, distinct way.

In the story, two such emotions stand out. One is Prendick’s distaste for the presence of the Hyena-Swine, who is clearly enjoying his opportunity to pin the crime and upcoming punishment solely on his accomplice, as well as sizing up Prendick for some further act. He reeks of hypocrisy, glee, and malevolence, perfectly displaying the stereotypes of mockery and profanity invoked by the animals he’s made from. However, those stereotypes have nothing to do with real hyenas or pigs but with people. Prendick despises the Hyena-Swine because he quickly and accurately recognizes his behavior.

The other is just before they find their quarry, when Prendick’s feelings for him change dramatically:

“Back to the House of Pain, House of Pain, House of Pain!” yelped the voice of the Ape-Man, some twenty yards to the right.

When I heard that, I forgave the wretch [the Leopard Man] all the fear he had inspired in me. (The Island of Doctor Moreau, p. 72)

When Prendick locates the Leopard Man before the others do, this feeling culminates in this crucial phrase:

It may seem a strange contradiction in me—I cannot explain the fact—but now, seeing the creature there in a perfectly animal attitude, with the light gleaming in its eyes and its imperfectly human face distorted with terror, I realized again the fact of its humanity. (Ibid., p. 72)

Victorian-era writers did not screw around with their word choice. It doesn’t say semblance of humanity, akin to humanity, or my impression of its humanity, or anything like those. It doesn’t even say humanity by itself, open to interpretation. Prendick abandons all such qualification—the word is “fact.”

What is human, at this point in the story? It’s explicitly not a being’s bipedal posture, or the possibility of its being mistaken for a member of our species, physically speaking. It is instead the Leopard Man’s understanding of his situation and his multiple resulting emotions: his recognition of being discovered, his terror of further torture, and what can only be called moral despair. Significantly, these fall into the category of the things Moreau earlier claimed he could not produce through his techniques, but which are now revealed to Prendick to exist, in this person, in a form he identifies with easily.

Whereupon Prendick, knowing that Moreau wants to return the Leopard Man to the laboratory both as an experiment in reprogramming and to demonstrate to the other Beast Folk that “none escape,” shoots him between the eyes. He does so from sympathy to prevent the suffering of a (i.e., any) living thing, but also from empathy, to relieve a fellow man of despair, both at that moment and in his inevitable agony later in the laboratory.

What mental operations make this possible? It lies in communication, which strictly speaking, is a carefully defined, social subset of perception. It happens when one individual perceives the signals of another, and acknowledges to the sender that they have received them. This behavior is very, very common among social organisms, employing a huge range of media and senses, of which the cognitive trick of language and the physical medium of vocalizing are subsets.

The real barrier to insight is our experience of language, which is all too easy to inflate in value, creating a circular argument. “We speak because we have special mental abilities, and we think in a special way because we speak.” Technically, language is indeed a neat trick: it folds two things together, vocabulary and syntax, with surprising results that neither can do alone. One such result in our species is recording content, so that older communications may become a teaching curriculum in later generations, which we call “culture.” It’s definitely distinctive as a historical combination of things, but not a new thing at an atomic level, because both vocabulary and syntax are observed across other living species.5

However, we make too much of it in several ways. For one, we consider the vocal medium that we use for this communication as the phenomenon itself, flying in the face of profound evidence that the use of sound has nothing intrinsically important about it toward such a function. For another, the recorded form of language has had drastic ecological consequences, not least our recent population explosion, but in this, it’s similar to many accumulated and multifaceted biological phenomena in many species. This discussion always boils down to identifying our population explosion as an achievement, a heroic triumph, a debatable point to say the least.

So I’ll break the circle. Like many other primates, humans are extremely good at the social form of cognition, permitting them to evaluate who is doing what to whom at many levels and across many individuals. Our map of social community is, perhaps, the central organizing principle of human cognition, such that we can hardly imagine “communication” without it. If so, then misidentifying our mode of communication, speech, as the cognition itself, or pulling the trick that all other forms are substandard because they do not use it, is a mire nearly impossible to escape. It means that we confound the capacity to communicate with membership of an acknowledged community and even with human status. Sadly, we constantly demonstrate this in the demonizing of other people simply due to differences in human language.

Understanding human cognition, then, lies in our particular social operation rather than the linguistic one. Work on social cognition has vastly improved in the past decade, but even some of the best discussion cleanly misses the crucial question: Does human behavior meet the criteria for the various goalpost-shifting concepts of consciousness? The discourse always takes it as given that it does, and as I see it, dives back into the intellectual hamster wheel encountered by so many of us who are interested in this topic.

That’s not to discount the research insights. One useful concept that’s emerged is called the language of thought, to investigate social and cognitive operations without getting distracted by verbal speech. The first insight is to recognize how widespread it must be, and how it might be worthwhile to consider other complex variables, like communicative devices besides vocalizations in other social animals, and equivalently complicated environments for non-social ones.

Social cognition and the suddenly shared language of thought are at the core of this moment in the story. However briefly, the whole situation suddenly becomes not Prendick’s place to say something, but the Leopard Man’s. Until this point, the Beast Folks’ ability to vocalize words had not by itself penetrated Prendick’s sense of shared community; it was not communication. Now, however, he cannot interpret this immediate situation in any other way as he acknowledges common values, fears, perceptions, and concepts. He’s not projecting. It’s not a guess. He “gets” the Leopard Man socially, and once the connection is made in that medium, then by definition, the two can communicate. The Leopard Man’s unvoiced statement strikes Prendick between the eyes as surely as the bullet will strike him in return: Please don’t let them take me.

Such an insight is life transforming. Prendick quickly translates his new grasp of the Beast Folk’s nuanced and above all familiar experience of their lives into equivalency between them and humans as he knows them. As he soon puts it,

A strange persuasion came upon me that save for the grossness of the line, the grotesqueness of the forms, I had before me the whole balance of human life in miniature, the whole interplay of instinct, reason, and fate in its simplest form. (The Island of Doctor Moreau, pp. 73–74)

This is as far from the “don’t meddle” science fiction horror story as you can get. Prendick is briefly unconcerned with the creations’ potential for violence (“Oh no, they’re really animals, they’ll turn savage and eat us!”). Instead, his sympathy to their physical plight as nonhuman victims of torture expands dramatically to empathy with their emotional, intellectual, and spiritual plight as people like himself. He isn’t even patronizing about it—it’s nothing to do with the Leopard Man being as good as a person, but rather that the totality of personhood and the Leopard Man, with all his faults and fears, are the same.

A lot of “don’t meddle” stories cast the subject of the abominable experiment as a tragic victim, especially when it’s rejected: the creature is angry because it is different, because it is cast out, because it is isolated and unloved. That’s not what happens in this novel. The Beast Folk do not rage and revolt—they putter along, living their lives, getting married, and growing their vegetables. They stumble frequently in the eyes of the Law, and try to make the best of it. Their failures and grotesqueries are ordinary, not fantastic results of their fantastic origins.

The Leopard Man happened to go under. That was all the difference. (Ibid., p. 74)

It wasn’t his Animal urges, beneath our lordly status or our Man or Angel side, that dragged him under “back to the beasts,” but plain old urges, any urges, such as you or I might feel and similarly struggle with, and which dragged him exactly to the emotional and social crisis where you or I might well go. He did a bad thing a person might do. Looking back over his story, I think the Leopard Man’s “No!” is not evidence of his alleged bestiality, but rather the defiant cry of someone who can no longer stand feeling guilty for something he did, yet still feeling it, who will rebel even harder if he’s criticized.

Prendick may be forgiven his insensitivity to these nuances, perhaps, as he began their interaction with being stalked and then attacked in the forest at night by a man who is also a leopard. It could be said that this initial moment was pure rotten luck for both of them, as given a chance, Prendick might have listened to him. As it went, though, he failed to see the community-and-communication medium they shared, and realized too late that this other person might have something to say.

Two of the films make use of this subplot, but they both distort its core features to the point of incoherence.

In The Island of Doctor Moreau (1977), the sequence is split into three characters, including M’Ling as the sucker-up of drink, who is then reprogrammed in much agony, then a cat-like, possibly tiger-based man who chases Braddock through the forest and attacks him on sight in defiance of the Sayer of the Law, and who is similarly reprogrammed, and finally the bull-man who defies the Law in the name of “Animal! Proud!” and goes on a rampage. The two violent rebellions seem to be expressed as a random, incomprehensible desire to fight the most dangerous opponent available for no reason, in the latter case an unmodified tiger that has escaped its cage. Spectacular and terrifying as it is to see a stuntman wrestle an actual tiger (no CGI back then!), it makes almost no sense at all. After another group confrontation with Moreau, the bull-man flees in fear of the House of Pain, chased by everyone. His final scene retains some of the pathos in the novel, when he pleads for Braddock to shoot him, “No House of Pain … kill,” which he does. The lack of prior interaction between them, though, leaves it as a toss-up between a moment of genuine connection between two people and the more familiar, “don’t meddle” concept of “We belong dead” as realized by a wretched, science-created monstrosity. The idea that the bull-man is more human than Braddock thought is at least possibly present in his understandable desire not to be painfully brainwashed, but is also undercut by his expression of “Animal!” as an urgent and apparently constant desire to fight.

The corresponding events in The Island of Doctor Moreau (1996) at first accord slightly more with the novel, featuring a leopard-man named Lo-Mai (Mark Dacascos) who kills a rabbit, the confrontation between Moreau and the Law-abiding Beast Folk community, the hyena character who hides his complicity, and the ensuing brief attack on Moreau. However, Douglas has no relationship with Lo-Mai and plays no role whatsoever in his eventual fate, when even as he submits to Moreau, he is unexpectedly shot by Azazello, the dog-man. The latter is obviously smugly pleased with murder, has inexplicably been given a gun by Montgomery, and is equally inexplicably not punished or limited in his later activities in any way. This point in the film marks its veering into many unmotivated or logistically hard-to-follow events, and whatever intellectual content or emotional resonance might have been evoked is lost.

In terms of story pacing and plot significance, the insight into the Leopard Man’s situation is as fleeting as Prendick’s perception of it. There’s another, prolonged, step-by-step point of view, with considerably more impact on everyone in the story, if you’re not blinding yourself to it. It belongs to the puma (in the US, mountain lion) who arrives on the island with Prendick.

She is mentioned and described throughout Chapters 3 through 8, from Prendick’s recovery aboard the Ipecacuanha through his acceptance by Moreau, so it’s possible to trace her experiences in detail—most of them horrible, such as being cramped into her transport cage, or spun around by the tackle while being unloaded. Once arrived, her surgeries begin immediately. She doesn’t appear in Chapter 9 only because Prendick has left the compound to escape her screams, which are described so eloquently that when they reappear in Chapter 10, I find that I have retroactively extended them back through Chapter 9 even though Prendick couldn’t hear them.

Her voice changes in Chapter 10, after only a day or two of surgery, to the extent that Prendick is convinced that Moreau is operating upon a human person. In Chapter 14, Moreau speaks of intervening extensively into her brain, occasionally so distracted by his hopes for success (again, for a “rational being”) that he sometimes loses his train of thought when debating with Prendick. Whatever degree of human mental processing is developed by Moreau’s techniques, which as I argue in this chapter is considerable, is well along its way. It’s also at this point that the reader learns her gender.

By the opening of Chapter 17, after the six-week break in Prendick’s narration, she has been subjected to almost two months of constant and extraordinary agony, permitted to heal between sessions only to be set upon again. When Moreau enters his laboratory, she shrieks, and here the text employs an interesting term:

So indurated was I to the abomination of [Moreau’s laboratory], that I heard without a touch of emotion the puma victim begin another day of torture. It met its persecutor with a shriek almost exactly like that of an angry virago. (The Island of Doctor Moreau, p. 75)

Some of the criticism I’ve read focuses on the negative implications of the word, similar to “bitch,” “hysterical,” and “uppity,” but I also consider its older, original meaning: a woman of strength, assertion, presence, and force, willing to defy social norms without denying her sex.

What happens then is simple: she does what no other Beast Person has done, even those made from animals probably stronger than she is, such as the oxen or the bear. Either she pulls her chain out of the wall upon seeing Moreau, or she did so during the night and has been waiting for him. She hits Moreau with it—not employing her teeth or claws—and breaks Prendick’s arm on her way out of the compound, then runs onto the beach. When she perceives Moreau pursuing her she takes to the brush, escaping him briefly.

The confrontation between her and Moreau must be reconstructed from what Prendick and Montgomery find almost a day later. When Moreau caught up to her, he shot her through the shoulder, but she was still able to kill him, again using the chain. She collapsed from loss of blood from the bullet wound, and she either bled to death or was too weakened to defend herself from the other Beast Folk. Her body is found “gnawed and mutilated.”

Several authors have investigated the character regarding fear of women and their oppression by Victorian and later society, especially in light of the prevailing ideas that women are more emotional and therefore more animalistic than men, unless subjected to male authority, up to and including surgical intervention. I agree with and recommend Coral Lansbury’s discussion of that issue in The Old Brown Dog, but I’m focusing instead on the character’s active and decisive role, rather than solely her victimization.

The Puma Woman, as I shall call her, is an actor, not merely acted upon. She extends the Leopard Man’s relatively passive defiance, becoming more than a skulking victim and sinner. Consider her experience just prior to the escape. What did she know? What did she think? How long did it take to get that chain out of the wall—was it a sudden surge of adrenaline, or had she tried all night—or even, possibly, over many nights?

Her cry, “almost that of an angry virago”—isn’t it the most easily identifiable moral voice in the story? Her agonized screams provided the backdrop to Moreau’s and Prendick’s debate in Chapter 14—now, isn’t this new cry, delivered not in agony but in anticipation, effectively her decision to participate in that debate herself?

Here the story taps into the issues of justice that Moreau’s and Prendick’s debate missed entirely. She has something to say, or to do, precisely about what is being done to her. Or to put it rather more bluntly, what might the vole have said to me?

I’ve criticized the movies a lot, but I’ll give their creators credit for examining the puma’s potential as a major character, especially since they don’t merely glamorize and objectify her. Her decisions and sexuality are a serious plot point begging to happen, and the films do come through in varying ways, generating deep ambiguity regarding whether this character “should” exist and given that she does, what degree of empathy, attraction, and admiration she merits, and most especially, what she chooses to do.

In Island of Lost Souls, in addition to the unscientific craziness I discussed previously, Moreau is even more perverse in his sexuality, always expressed through some hypothesis test or other. He sets up Parker and Lota for romance—successfully!—and lurks in the shadows to watch them kiss, then he sets up Parker’s fiancée Ruth to be raped by Ouran, all in the name of testing how human his creations have become. Film writers have a field day with him, including the explicit sublimation (no one ever looked more like an impotent voyeur than Laughton’s Moreau) and the racist stereotyping of the exotic, innocent native woman who wants nothing more than to keep the mighty white man by her side, and the bestial, grinning native man, who needs only glance at the white woman to become obsessed with raping her. The literature on that matter is fascinating, but my aim is a little different.

Although this film’s plot is the pure, even distilled “don’t meddle” story, Lota’s role in it is deeper, including some positive elements of the novel’s Leopard Man and Hyena-Swine, aided by a remarkable performance by Kathleen Burke. Her moral status, which is to say, how to think of her, is dramatized by the escalating romantic triangle among Lota, Parker, and Ruth. The triangle is resolved orthogonally, rather than through a direct conflict, when Lota sacrifices herself to save the others from Ouran. Ruth never learns about the knee-weakening kiss, for instance. I was a little disappointed not to see Parker forced to choose between the two women, which would entail deciding whether Lota is human or not. Her final actions spare him that choice even as they nail that very issue to the wall—in her favor.

In Terror Is a Man, the romantic tangle is effectively the whole story, with Girard’s wife Frances at the center of all four principal men’s interests, including her husband as a driven but sane version of Moreau and the nearly complete Panther Man. The gender switch doesn’t change the issue, because the Beast Man turns out to be rather admirable toward her, especially in contrast to Walter the debased assistant, and even in contrast to Fitzgerald, the protagonist. As in Island of Lost Souls, the sexualized and emotionally sincere Beast Person is sympathetic, but in this case, as the only Beast Person in the story, he’s also the source of lethal danger to others every time he gets loose. Fitzgerald’s opinion of him captures that dilemma, as he states that upon looking into the Panther Man’s eyes, he sees a soul, but he also fears the created man’s evident urge to kill—as if a tormented, restrained person would not return a captor’s scrutiny with the desire to strike back.

The Panther Man’s final confrontation with Girard is almost exactly the same as the Puma Woman’s with Moreau in the novel, and his death seems quite sympathetic to me. I can’t help wishing that his murderous attacks on the natives had been left out of the plot, such that his lethality would have been limited to his tormentor Walter. In that case, the story’s rather well-developed question, “what makes a man,” might have been thrown into unique focus through Frances’s eyes.

The main conflicts in Twilight People are also rooted in romantic tension, although in this case, only among three fully human characters and with one corner being explicitly homoerotic. The Panther Woman, Ayessa (Pam Grier), isn’t part of this story at all, so adds little to my present point, aside from being the film’s unquestioned most righteous bad-ass and killing a slew of Doctor Gordon’s goons. Her presence accords more with Jennifer Vere Brody’s analysis in Impossible Purities, as the films, especially this one, generally go further than the novel ever does in exoticizing the Beast People in ethnic terms. My point is still supported, though, in that Gordon meets his end at the hands of his wife, now severely transformed by his experiments.

In The Island of Doctor Moreau (1977), Maria (Barbara Carrera) is presented such that she may or may not be one of Moreau’s creations, despite many hints, and she and Braddock do become lovers. However, this plot thread or question becomes a bit lost in all the mayhem until the very end, where I find myself muddled slightly—because I would swear on a stack of Metropolis DVDs that when I first saw this movie in my mid-teens, Maria is clearly reverting to her panther form in the final moments, in perfect mirror to Braddock’s recovery from Moreau’s animalizing serum.6 I was looking forward to seeing the final scene again, but on the currently available DVD, what do I find? The final shot of Maria’s face isn’t at all what I remember, but that of an ordinary woman with maybe the barest touches of makeup to suggest otherwise, if that. Was she a creation of Moreau’s or wasn’t she? Answering “no” makes no sense, considering multiple lines of dialogue and crucially, that Moreau was shown to be observing the earlier sex scene in a clinical fashion, but the visuals lean more toward “no” than “yes.”

As the single unfortunate exception, in The Island of Doctor Moreau (1996), Aissa (Fairuza Balk) is deeply marginalized by the script, which makes her less of a positive virago and more of a waif. She’s a cat, not a puma, and her action is limited to wavering between ineffectually helping Douglas and irrelevantly tending to Moreau. Even her catlike qualities are weak when she needs them, as she gets beaten up easily by the dog-man, and she ultimately ends up the victim of trying to please too many people at once—not exactly the route the original puma character or the other film versions of her would take.

At the other end of the spectrum is Doctor Moreau’s House of Pain (2004), in which Alliana (Lorielle New, mis-credited as Loriele New) is—“objectified” is about the mildest way to put it, as she works as a stripper, which is filmed as to leave no doubt, seeks a suitable mate, ditto, and deals with an annoying man by punching her fist through his head. However, there’s no question that the film is also working with motifs relevant to what I’m discussing in this section. She and the other transformed animals in this film hold a lot of agency, making decisions as least as important as those of the human characters, and New’s performance is similar to Burke’s in Island of Lost Souls in combining catlike movement with undeniable personhood. Alliana’s final decisions are more vicious and self-centered than Lota’s, but they cannot be described as brutish or subordinate; for instance, unlike Lota, her sexual and romantic focus on Carson is not ordered or manipulated by Moreau but completely under her control.

Prendick’s changing gaze culminates in retreat, ending in utter exceptionalism and, in the face of experiences that contradict it, break down. It begins with that full and sudden flip that starts in Chapter 17. After six weeks pass, about which Prendick reveals almost nothing, he has adopted Moreau’s idealized view of Man and actively suppresses the fact that the latter’s words criticizing the Beast Folk inadvertently describe people perfectly, or that he had seen the fact of their humanity for himself.

. . . I had lost every feeling but dislike and abhorrence of these infamous experiments of Moreau’s. My one idea was to get away from these horrible caricatures of my Maker’s image, back to the sweet and wholesome intercourse of men. My fellow creatures, from whom I was thus separated, began to assume idyllic virtue and beauty in my memory. (The Island of Doctor Moreau, p. 75)

Weird! I would think, after his insights at the end of Chapter 16, that he’d go straight back to the lab and insist that the Puma Woman be freed. But he doesn’t, and after six more weeks of listening to her scream, he’s “untouched by emotion” and coming up with all this hate speech.

He’s also avoiding Montgomery like the plague, and no wonder: the assistant is all too evidently a person, rather than a paragon of virtue and beauty.

Prendick never found his way into a gaze that wasn’t his own, which is why he failed to help the Leopard Man in time. As for the Puma Woman, he fails to help her at all, completely missing her presence in the situation, despite it being his primary sensory experience throughout most of the first half of the book. The reason why is twisted up in that strange six weeks of silence between two chapters, and what can only be interpreted not merely as happening to miss her, but refusing to look.

The power in this portion of story arises, at least as I see it, from forcing the reader—you and me—to look instead, to challenge the Man/Beast divide in precisely those places we cling to it: our “intelligence,” our “awareness,” and our over-vaunted verbal tricks. It’s laid upon us to make the connection that Prendick could not.

The literary power of that point is stunning, even historically heroic given the period, and given that the same conundrum ties our intellectual culture in knots. It gets further than Huxley did, and further than Wells would achieve again.

James Rachels, Created from Animals (1999), provides a good summary of Darwin’s work on nonhuman decision-making and problem-solving. The definitive reference is Robert J. Richards, “Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behavior” (1987).

Academic writing on human thought is contentious, so the following titles are recommended as an assemblage of slightly differing views and as portals to their extensive bibliographies: Marc Hauser, Wild Minds (2001); Mark S. Blumberg, Basic Instinct (2005); Edmund O. Wilson, On Human Nature (1994); Stephen Pinker, The Language Instinct (1995) and The Blank Slate (2003); Timothy Goldsmith and William Zimmerman, Biology, Evolution, and Human Nature (2000); James Gould and Carol Gould, The Animal Mind (1994); Dorothy Cheney and Robert Seyfarth, Baboon Metaphysics (2007); and Temple Grandin, Animals in Translation (2004). Technical mind-and-brain function references include M. Deric Bownds, The Biology of Mind (1999); and John Dowling, Creating Mind (1999).

Intersections among clinical psychotherapy, social deconstructionism, and literature can be found in Paul Gilbert (editor), Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research, and Use in Psychotherapy (2005), especially Chapter 8: Neville Hood, “Cosmetic Surgeons of the Social.” Further historical and gender analysis are available in Jennifer Vere Brody, Impossible Purities (2012), and Coral Lansbury, The Old Brown Dog (1985).

The Elsevier Trends journals published by Cell Press are one of modern biology’s brightest lights, publishing reviews and opinion pieces in the hope of bringing current debates to the attention of multiple disciplines, highlighting unusual points of view, and sparking new questions, and best of all, many articles prompt fierce debates in subsequent issues. There are fourteen titles, including Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, and Trends in Molecular Medicine. Most universities have licensed them for free reading online, so if you have access, I can recommend no better source to keep up with what bioscience and biotech are doing at the edge of what we don’t know.

1.The connection with Freud’s writings is direct: the id is defined as repressed stages of thought from older evolutionary conditions, primitive predispositions from prior organismal identity.

2.Credit for this one goes to Leon Eisenberg, “Mindlessness and Brainlessness in Psychiatry,” British Journal of Psychiatry 148(5): 497–508, 1986, although, as his title states, he was discussing clinical care, not the broader behavioral and evolutionary field.

3.Trends references:

•Regions of the cerebral cortex

•Steve L. Franconeri et al., “Flexible Cognitive Resources: Competitive Content Maps for Attention and Memory,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17(3): 134–141, 2013.

•Kalina Christoff et al., “Specifying the Self for Cognitive Neuroscience,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 15(3): 104–112, 2011.

•Cell functions within the cortex

•Matthew Larkum, “A Cellular Mechanism for Cortical Associations: An Organizing Principle for the Cerebral Cortex,” Trends in Neurosciences 36(3): 141–151, 2013.

•Anis Contractor et al., “Kainate Receptors Coming of Age: Milestones of Two Decades of Research,” Trends in Neurosciences 34(3): 154–163, 2011.

•Hiroaki Wake et al., “Microglia: Actively Surveying and Shaping Neuronal Circuit Structure and Function,” Trends in Neurosciences 36(4): 209–217, 2013.

•Min Fu and Yi Zuo, “Experience-Dependent Structural Plasticity in the Cortex,” Trends in Neurosciences 34(1): 177–187, 2011.

•Gianfranco Dalla Barba, “The Hippocampus, a Time Machine That Makes Errors,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17(3): 102–104, 2013.

•Sara A. Burke and Carol A. Barnes, “Senescent Synapses and Hippocampal Circuit Dynamics,” Trends in Neurosciences 33(3): 153–161, 2010.

•Howard Eichenbaum, “Memory on Time,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17(2): 81–88, 2013.

•Oliver Hardt et al., “Decay Happens: The Role of Active Forgetting in Memory,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17(3): 111–120, 2013.

•Robert P. Ryan and J. Maxwell Dow, “Communication with a Growing Family: Diffusible Signal Factor (DSF) Signaling in Bacteria,” Trends in Microbiology 19(3): 145–152, 2011.

4.The word “intelligence” lacks scientific content and has probably been corrupted permanently in its use as a performance variable in stress-testing that we call IQ tests. If it were to be rehabilitated, it would certainly not include that type of performance. See Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (1982).

5.Vocabulary is a catalog of representations used in communication, “words” in the general sense; one’s vocabulary is typically acquired through examples. Syntax is a cognitive framework of rules or techniques for constructing sentences; it underlies grammar and makes language as we know it possible. The honeybee provides an excellent example of a nonhuman that uses syntax. It may be more useful, however, to consider communication as such before language as structure, as demonstrated by Uri Hasson et al., “Brain-to-Brain Coupling: A Mechanism for Creating and Sharing a Social World,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16(2): 114–121, 2012.

6.I remember speculating that it would have been awesome if Braddock had died in the final fight, and if the approaching ship’s crew would have therefore discovered nothing in the boat but a panther.