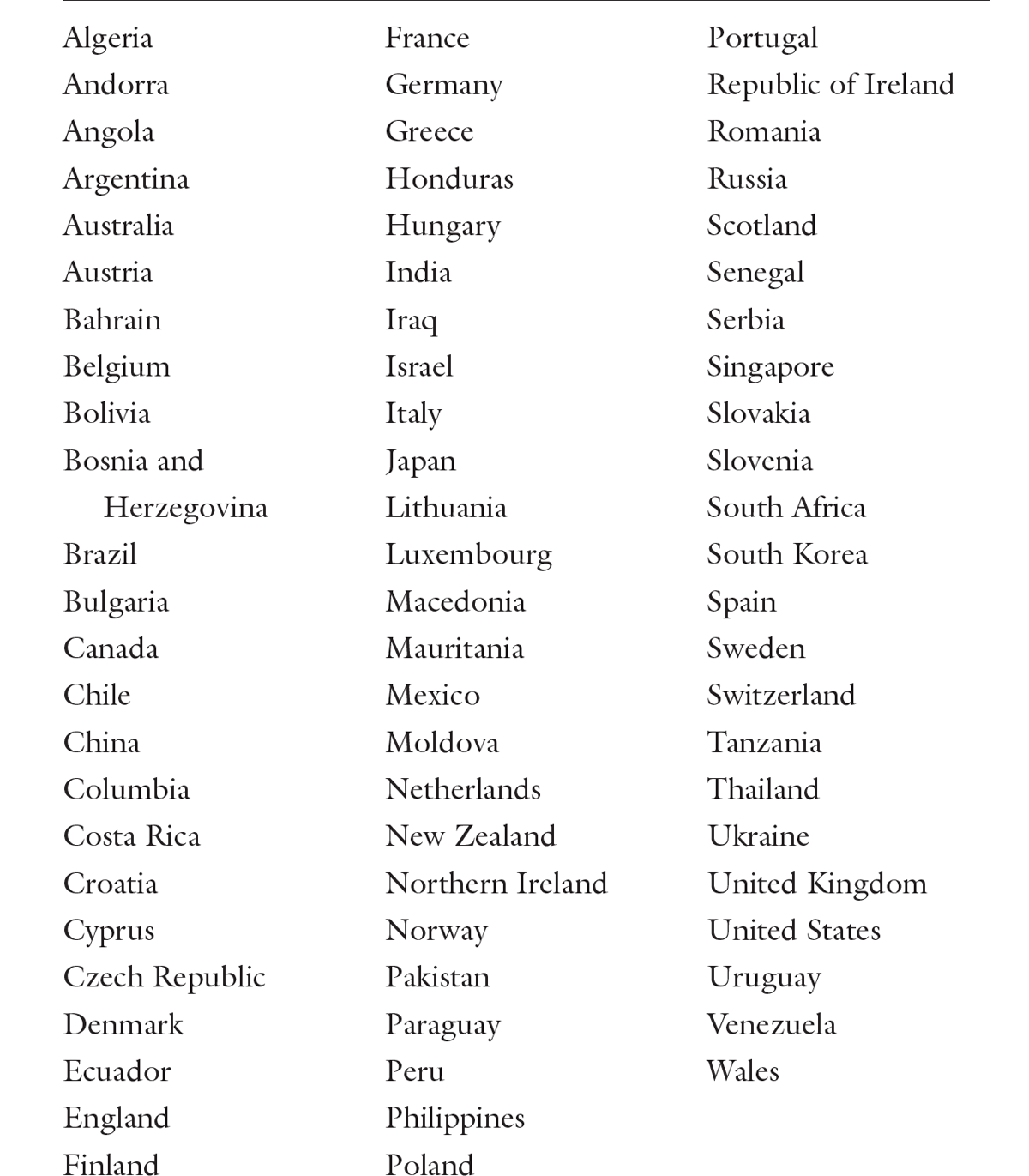

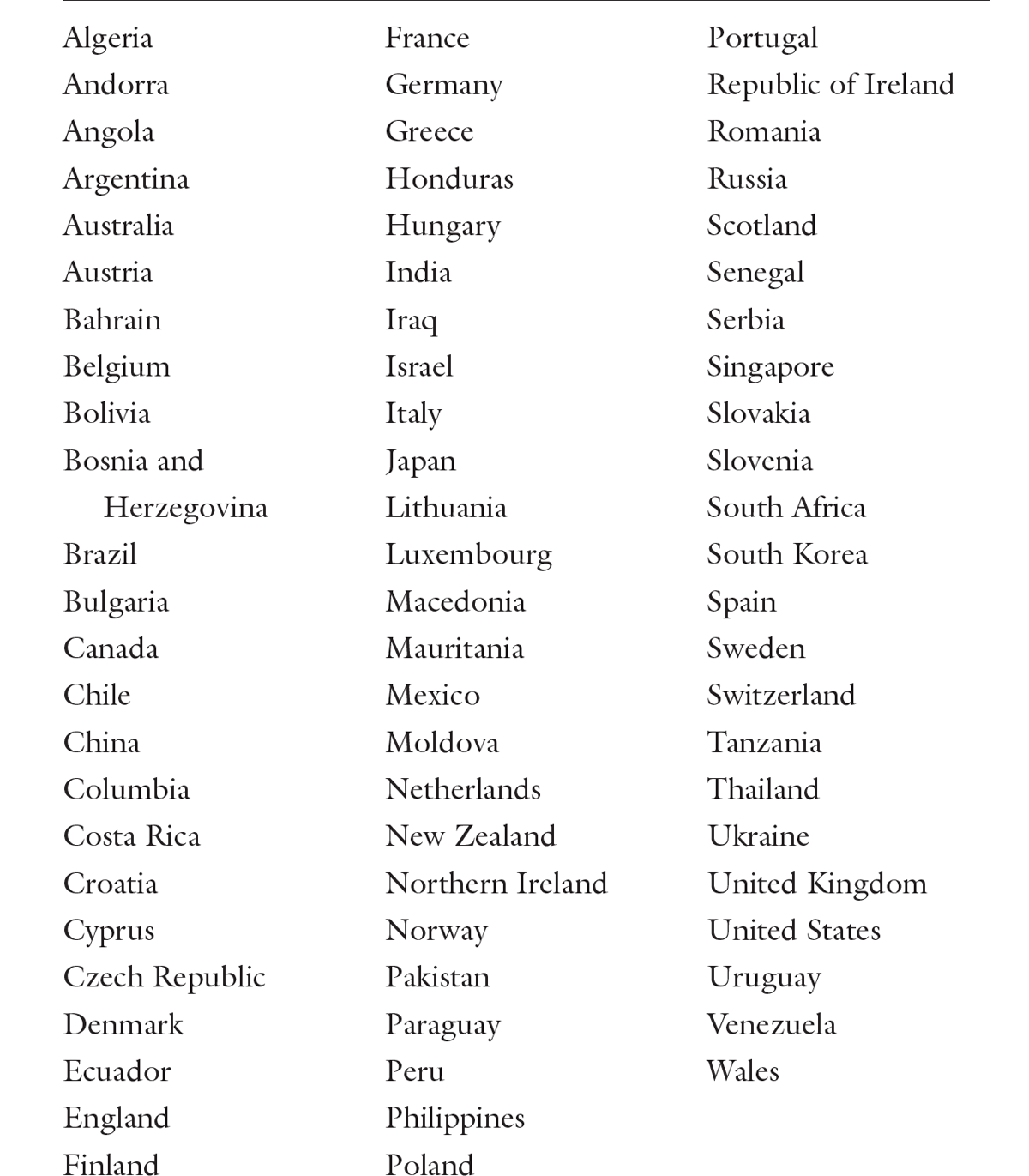

Table 5.1. List of countries with dedicated QAnon Facebook pages.

Source: Marc-André Argentino, “Twitter / @_MAArgentino: Lets Talk About QAnon Worldwide . . .” (August 8, 2020).

QONTAGION

On August 22, 2020, 200 street rallies were held across the United States, Canada, and European countries, as well as in eleven cities and towns in the UK, under the slogan “Save Our Children.” #SaveTheChildren was a fundraising campaign for the UK-based charity Save the Children, but the hashtag was hijacked by QAnon believers in July 2020, leading Facebook to temporarily disable it after it became awash with misinformation.1 In “band-wagoning” onto the charity’s hashtag, QAnon took root in the social media timelines of middle- and upper-class women who would never consider affiliating with an online conspiracy theory except for one that appealed to their maternal instinct.2 What is noteworthy is that the visuals used as part of the QAnon hashtag #SaveTheChildren featured battered and bruised children, almost all of whom were white. Long past are the days of Sally Struthers’s entreaties for donations to Christian Children’s Fund, which showed mostly non-white children with distended bellies and covered in flies. In contrast to the graphic images posted by QAnon, the actual Save the Children charity features smiling children from Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.

In Chapter 1 we explored how the COVID-19 pandemic supercharged conspiracy theories—but none so much as QAnon. As the pandemic is a global phenomenon, so too have the conspiracies gone global. With QAnon’s growing popularity in the United States, it has likewise metastasized to dozens of other countries from Brazil to Germany, France, the Balkans, the UK and Indonesia.3 In June 2020, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue counted 450,000 members of QAnon on the European continent.4 However, this figure is probably only the tip of the iceberg. The conspiracy theory has managed to attach itself to local grievances in countries around the world, and in doing so it successfully blends anti-government, anti-lockdown, and anti-Semitic rhetoric with its beliefs about the global pedophile ring.

QAnon has grown internationally in two ways: By embracing local grievances and coopting local interests, QAnon resonates with an international audience; and by embedding itself with particular strains in Christianity, it communicates a degree of legitimacy. Two countries have amplified QAnon disinformation with the goal of undermining people’s trust in institutions: Russia and China.

The Gospel of Q

In the United States, QAnon has infiltrated several religious denominations: Catholicism, Protestantism, and the evangelical church. Evangelical Christians elevated Trump to godlike status in 2016 when they put their full support behind then-candidate Trump. In the United States, AEI conducted a survey after the January 6, 2021, failed insurrection at the Capitol. The results of the survey defy logic; they found that 29 percent of Republicans and 27 percent of white evangelicals—the most of any religious group—believe the widely debunked collection of Q-conspiracy theories is completely or mostly accurate.5

QAnon infiltrated several Christian denominations besides evangelicals, including 15 percent of white Protestants, 18 percent of white Catholics, 11 percent of Hispanic Catholics, 7 percent of Black Protestants, 22 percent nonaffiliated, and 12 percent of non-Christians.6 As the conspiracy belief seeped into the religious fabric of U.S. life, it merged with the proselytizing zeal of some of these groups. Left unfettered, it is equally likely that traditional missionary work by Christian groups will become imbued with Q ideology.

As it has absorbed local grievances abroad, among evangelicals, QAnon blended its beliefs with religious dogma, cherry-picking verses from religious texts to substantiate its most outlandish claims. Despite so many of the QAnon predictions failing to manifest, evangelicals proselytize the conspiracy theory with the same religious zeal they bring to their missionary work. Adrienne LaFrance, editor for The Atlantic, has suggested that QAnon is not an everyday conspiracy but it is becoming a religion in its own right.7

QAnon spread among evangelicals for the same reasons that conspiracy theories increased multiple times over: as a result of the pandemic and quarantine. Instead of attending Sunday services in person, people were forced to worship at home without the benefits of group cohesion, comfort, and community. Without this succor, they experienced loneliness and isolation. Like the rest of the world, they spent additional hours on Facebook and the Internet. What made evangelicals especially vulnerable to QAnon was that the language and terminology that QAnon used sounded explicitly Christian, debating the existence of good and evil. The primacy of prophecy and the concept of the “Great Awakening” resonate with evangelical Christians because for many believers this describes how they experienced their own path to finding Christ or their prophecies about the Rapture.

QAnon has coopted Christian-sounding ideas to promote their false claims. The movement is imbued with Christian theology and language, with Q regularly quoting from the Bible and urging his followers to “put on the armor of God.”8 This language and these references resonate positively precisely because they are familiar and ingrained. The clearly defined gulf between good and evil in which the other side is completely vilified (as blood-drinking pedophiles) promotes a type of dehumanization and intense othering.9

Katelyn Beaty, a writer for the Religion News Services, interviewed evangelical pastors whose worshippers were falling down the QAnon rabbit hole. One pastor from Missouri—Mark Fugitt of the Round Grove Baptist Church—recounted all the conspiracy theories that his parishioners had been sharing on social media. The list included claims that 5G is an evil plot for mind control; that George Floyd’s murder is a hoax; that Bill Gates is related to the devil; that wearing masks might kill you; that the pandemic isn’t real; and that there might be something to Pizzagate after all.10 On the TV news show 60 Minutes, Leslie Stahl interviewed Derek Kabilis, a pastor from Ohio, who has been more aggressive in calling QAnon a heresy.11 However, the vast majority of Christian pastors have been reticent to take a stand against QAnon for fear of losing parishioners from their ministry to the conspiracy theory.

The leaders of the evangelical church are witnessing a crisis of authority in institutions—the government, the press, and even their own church—a crisis that is leading people to QAnon. Some pastors attributed the spread of QAnon to the so-called “death of expertise”—a distrust of authority that leads some people to undervalue competency and wisdom and where ignorance is considered a virtue.12

According to researcher Marc-André Argentino, one church in Indiana—the Omega Kingdom Ministry (OKM), led by Russ Wagner—hosts a two-hour Sunday service showing how Bible prophecies confirm QAnon’s messages. OKM’s leadership includes Kevin Bushey, a retired colonel who ran for election to the Maine House of Representatives in District 151. Wagner and Bushey advise their congregation to avoid the mainstream media (even Fox News and NewsMax are Luciferian in their estimation) in favor of QAnon YouTube channels or tracing Q-drops using the Qmap site developed by Jason Gelinas.13 When evangelical Christians shun mainstream media, this exacerbates the problem of misinformation:

The distrust in mainstream media and that willingness to write off mainstream media information as fake news opens the door for evangelicals to turn to alternative and fringe news sources, including those that traffic in conspiracy theories.14

Beginning in 2011, Trump actively courted evangelical support and appeared on the Christian Broadcasting Network, having been coached by Paula White to appeal to a religious Christian audience. As someone who could not cite even one biblical verse, Trump seemingly pandered to evangelical priorities (opposing abortion and same-sex marriage). When Trump finally launched his campaign in 2015, the evangelical base was surprisingly enthralled. Many evangelicals till this day claim that Trump was the most pro-life president ever to grace the office.15 Trump’s shared grievance with evangelicals—that the political, legal, and social changes in the country robbed Christian America of what they considered to be God’s intention for the United States.

Support for Trump among evangelicals has been consistently high despite their dwindling numbers as their children migrate from the church’s beliefs. Many evangelicals believe that God has chosen Trump, an unlikely leader, to lead the country in challenging times and to restore it to greatness.16 In surveys, over 6 out of 10 (63%) evangelical Christian Republicans believed that an unelected group of government officials, known as the deep state, were trying to undermine the Trump administration. Despite pastors ignoring it or a handful opposing it, between 27 and 30 percent of evangelicals continued to believe in the conspiracy theory.17

One possible explanation for why evangelical Christian Republicans are more likely to embrace conspiracy theories is their affinity to Trump. Trump played an active role in promoting misinformation.18

One of the major evangelical QAnon influencers is Dave Hayes, who uses the pen name “Praying Medic.” The Praying Medic persona has amassed more than 750,000 followers across Twitter and YouTube. This Arizona-based evangelical faith healer has become a popular and influential interpreter of QAnon writings, and he is one of the most influential QAnons in the world. Hayes often meets with international QAnon supporters.19

Eighty percent of evangelical church members support Trump, and 29 percent also support QAnon. By embracing adjacent conspiracy theories—for example, the anti-vaxx movement—QAnon has filtered into other religious organizations that are likewise anti-vaxx, including (most shockingly), Orthodox Jews. One would have assumed that the anti-Semitic content of QAnon’s beliefs would appall Jews. However, the Orthodox community in the United States overwhelmingly supports two elements consistent with QAnon beliefs: support for Trump and vaccine skepticism.20

While Silicon Valley began shutting down Q Facebook pages and Etsy and Twitter accounts in the summer of 2020, some new groups emerged to entice new followers. They migrated to new platforms like Parler and Gab and a few unexpected ones (like Peleton or Nextdoor).21 Even after aggressive de-platforming of the biggest QAnon Twitter influencers in October 2020, in the month leading up to the election, as many as 93,000 channels remained.22 Users also found a variety of ways to fool the moderators and the automatic enforcement systems by changing their hashtags or using the number 17 instead of the letter Q—for example, #Q17, #17Anon, or #CueAnon. Facebook has taken down thousands of pages but could not take down individual accounts that did not violate its terms of service. A British report from the group Hope Not Hate summarized the de-platforming whack-a-mole problem succinctly: “[A]ny action against them will therefore require endless vigilance against rebranded replacements repopulating the platforms.”23

However, by this point, the conspiracy theory had crossed the Rubicon. QAnon had gone global.

As social media companies were pulling down QAnon Facebook pages in the United States, new social media pages appeared in “Austria, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, Russia, and Israel.”24 In July 2020, Vice News began to document the global scope of QAnon, with thousands of followers in 25 different countries from the UK, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Russia, and even Japan and Iran.25 One QAnon researcher tracked the conspiracy through Facebook pages in 71 countries around the world (Table 5.1).26 Figure 5.1 shows the global spread of QAnon followers.

This internationalization presents an uphill battle for social media companies already facing increased pressure from governments to combat disinformation on their platforms in English, let alone a myriad other languages.27

In the international chapters of QAnon, the role that former President Trump plays varies. According to Melanie Smith of Graphika, QAnon subsidiaries in Japan and Brazil rely less on Trump as the focal point and are self-sustaining as an ideology.28 In Japan, General Michael Flynn is QAnon’s focal point more than former President Trump. Japan is a receptive milieu to conspiratorial thinking in part because Mü magazine has peddled various conspiracies for 40 years, and 2chan originated in Japan.29 Based on Graphika’s research, General Flynn is aware of his influence in Japan and follows several QAnon influencers in the Far East, including one woman whose Twitter handle was @okabaeri9111 (Twitter deleted the account as part of the crackdown on QAnon-promoting accounts). Eri Okabayashi ran the Japanese QAnon community (sometimes called “J-Anons”), which reportedly had more than 80,000 followers and claims she is both the founder of QArmyJapanFlynn (Qmap Japan) and the official translator of Q content into Japanese. Okabayashi’s interest in QAnon stems from her deep-seated qualms about Japan’s treatment of women and motherhood.30

Table 5.1. List of countries with dedicated QAnon Facebook pages.

Source: Marc-André Argentino, “Twitter / @_MAArgentino: Lets Talk About QAnon Worldwide . . .” (August 8, 2020).

According to the New York Times, however, most Japanese do not subscribe to J-Anon’s eccentric theories—including that the imperial family has been replaced by body doubles or that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were cover for a jobs-creation program for the interior.31 Japan is largely resistant to disinformation, partly because of its laws regarding fair media practices, partly because its newspapers have substantial circulations, and partly because of its high levels of literacy. Such mitigation strategies might be useful for countries trying to inoculate against dangerous conspiracies.

In most of the European QAnon chapters, Trump maintains his prominent place as the chosen one to save the children. In countries like Germany, Trump is the savior who will rescue the people from Angela Merkel’s corruption.32 QAnon has made deep inroads in Germany with hundreds of thousands of supporters (200,000 in October 2020) and increasing every month. The German-language Qlobal Change network has 106,000 subscribers to its YouTube channel and 122,000 subscribers to its Telegram channel.33

Like the United States, the German far right has latched onto Q. The conspiracy theory in Germany coalesced around a NATO joint military exercise. Josef Holnburger, cited in the New York Times, insists that there is an overlap between far-right influencers and groups aggressively pushing QAnon.34 In Germany, QAnon brings together an ideologically incoherent mix of anti-vaxxers, fringe thinkers, and citizens who believe that the pandemic is overblown. The earliest QAnon evangelists were members of the Reichsbürger or “citizens of the Reich” movement, a blend of groups bonded by their common rejection of the German state. Their apocalyptic, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories dovetail with QAnon narratives. They believed that Trump would restore the Reich.35 A report by Network Contagion, a think tank run by former Republican Congressman Denver Riggleman, explains the contagion of QAnon in Germany:

Conspiracy theories about underground bunkers, aliens, and mind-control microchips already proliferated in the far right through 4chan’s sister site, Kohlchan and other sites. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing restrictions provided the impetus for a widespread illiberal resistance movement tied to the populist radical right party.36

German celebrities and influencers like R&B singer Xavier Naidoo and Libertarian politician Oliver Janich encouraged people to follow them down the rabbit hole. QAnon has managed to thrive in the country despite the fact that much of its materials is anti-Semitic. By German law, disseminating this type of material can result in five years in jail. The German right-wing opposition to Merkel uses Q slogans like “WWG1WGA,” and Jürgen Elsässer’s far-right publication Compact has featured a giant Q on its cover and since 2019 has dedicated several issues to the conspiracy theory.37

One German Facebook page AUGEN AUF (“eyes open”) has over 61,000 followers and posts conspiracy theory content, including memes that are shared over and over again. The German content mirrors the U.S. memes of following the rabbit and choosing the red pill. In one post, an image of a white rabbit includes the text “leave the matrix, time is up,” linking to one of the German-language Telegram channels, seemingly intended to avoid Facebook’s prying eyes (or AI used to locate the content).38

Attila Hildmann, a vegan chef, amplified QAnon propaganda on Telegram for months. He took Trump’s defeat hard and posted his “resignation” from QAnon to his 114,000 Telegram followers, calling Q a CIA “psychological operation.” While some supporters like Hildmann became disillusioned by Trump’s defeat, others remained hopeful. “As the Americans say, in God we trust,” one poster on a German Telegram group wrote. “Now is the time to trust.”39

QAnon Facebook accounts indicate even more global interest from the Philippines to Finland, Chile to New Zealand. QAnon in Brazil focuses on the close relationship between former President Trump and Jair Bolsonaro. In Brazil, second only to the United States in terms of COVID-19 casualties, Bolsonaro echoed Trump’s conspiratorial behavior and amplified Trump’s claims about the utility of hydroxychloroquine, the anti-malaria drug QAnon influencers believed could cure coronavirus.

QAnon absorbs local grievances and concerns—this is the secret to its success and growth. Anna Merlan has likened it to a “conspiracy singularity,” where multiple conspiracies merge into a melting pot of unimaginable density. She describes Q absorbing adjacent conspiracies such that all the conspiracy theories come together and overlap, drawing each other’s constituents.40 For other researchers, QAnon is an amorphous blob that changes based on the situation. “When things change, the story changes, too.”41 Elle magazine’s Anne Helen Petersen considers it to be an adaptable organism.42

We consider QAnon to be like a sticky ball, rolling down a hill; as it rolls, faster and faster, it picks up other conspiracies and their supporters along the way—growing ever larger over time. QAnon is a meta conspiracy theory offering something different for everyone and thus able to accommodate a large constituency that has little in common except for a shared belief in QAnon.

In Britain QAnon appeals to Brexit supporters; in Italy, it appeals to anti-vaxxers.43 In most of the European countries, the conspiracy theory is tinged with an antagonism toward immigrants and refugees. In the UK, QAnon Facebook groups debate whether Trump’s ally, Boris Johnson, is advancing “the plan” according to schedule. QAnon in the UK also merges antagonism about 5G. Prime Minister Johnson’s decision to ban Huawei from the 5G networks is proof of Johnson’s allegiance to Q. Like in the United States, UK celebrities play a role in disseminating the conspiracy theory. For example, pop singer Robbie Williams endorsed Pizzagate on Twitter.44

Merging with local issues, QAnon in the UK has been focused on Prince Andrew’s relationship to Jeffrey Epstein and the disappearance of three-year-old Madeleine McCann in Portugal in May 2007.

The long history of conspiratorial thinking in the UK has resulted in fertile ground for QAnon. Q-conspiracy theorists like Martin Geddes have hundreds of thousands of followers and can convey the conspiracy theory’s most absurd details using quasi-scientific thinking. In the Netherlands, social media accounts that align themselves with Geert Wilders, the Dutch far-right politician, merge QAnon elements with anti-lockdown measures.45

The number of posts and demonstrations can measure manifestations of QAnon activity in Canada, the UK, Germany, Romania, Poland, Australia, and Indonesia; we can also study a failed attack against Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The very same structural conditions that impacted the United States during the pandemic increased the appeal of QAnon internationally. Trudeau closed the Canadian border on March 21, 2020, to control the spread of COVID-19. However, this failed to stop the U.S. export of QAnon from traveling northward. QAnon surged in Canada just as it did everywhere else with the rise of Internet usage at home. As with everywhere else, Canadian QAnon followers drew together an amalgamation of yoga moms, yellow vests (gilets jaunes), anti-vaxxers, pedophilia obsessives, and white nationalists.46

The Canadian QAnon attempt against Trudeau (briefly mentioned in Chapter 2) occurred in July 2020 when a heavily armed reservist named Corey Hurren drove 2,600 kilometers (over 1,600 miles) from Bowsman, Manitoba, to Ottawa to ram his vehicle through the gates of Rideau Hall. Before the attack, Hurren posted Q-inspired content to his company’s Instagram account. After the attack, Hurren changed his story and claimed that he was actually motivated by financial problems caused by the pandemic. He had grievances against the government and was concerned about the prospect of losing his gun rights.47 Hurren pled guilty in February 2021 to seven counts of weapons possession and one charge of mischief from causing $100,000 worth of damage to the Rideau Hall gate.48 In another instance, a Canadian influencer, Amazing Polly, was implicated in the Wayfair allegations—disseminating QAnon propaganda before YouTube purged her account in October 2021. Another Canadian influencer, Danielle LaPorte, used her Instagram account to publicize the #SaveTheChildren hashtag that was hijacked by QAnon in the summer of 2020.

Hijacking the charity’s hashtag hurt children more than it helped the work of child protection. QAnon exaggerates trafficking statistics in order to communicate the enormity of the problem. Elle magazine explains that it is a distraction from agencies and nonprofits that have actually been doing this work for decades, “diverting resources that could be used to actually protect vulnerable children.”49 QAnon followers’ near obsession with child trafficking might have influenced the Trump administration to announce its campaign to “save the children.” A budget of $35 million announced by the State Department earmarked for trafficking turned out to be no more than an illusion. The money that former President Trump and Ivanka Trump publicized50 was never actually spent on trafficking initiatives51 despite reports to the contrary.52 Rather, the focus on child trafficking was part of the Trump administration’s wink toward a growing QAnon voting bloc of QAmoms.

While some U.S. QAnon supporters were starting to lose hope after the 2020 election, the Canadian QAnon channels continued to organize protests in several Canadian cities and circulated the (false) claim that Justin Trudeau planned an “immediate military intervention on American soil” if Trump refused to concede.53

In France, the DéQodeurs website is the entry point into the French QAnon galaxy. The French version mixes philosophical esotericism with disinformation and extremist rhetoric. The local connection is with the yellow jackets protest movement.54 As is the case throughout Europe, French QAnon melds local issues while highlighting QAnon’s usual priorities. French President Emmanuel Macron is part of the cabal. The French QAnon movement describes itself as

[a] group of French, anti-globalization patriots, who campaign to wake up Nations . . . to inform the French people, and more generally, all Francophones that are manipulated by traditional media on today’s worldly stakes.55

French QAnon has posted news clips from Russian Television (RT) and repeated disinformation about the U.S. Democratic Party being filled with pedophiles alongside thinly veiled racist articles about George Floyd. The French government is understandably concerned. Macron ordered a multi-agency inquiry into conspiracy theory movements, while French security agencies have been investigating the intersection of QAnon with neo-Nazism.56 The individual credited with QAnon’s popularity in France is Léonard Sojili, an Albanian 9/11 “truther” who began posting online disinformation in 2011 and started disseminating the QAnon conspiracy theory on a YouTube channel called Thinkerview, which boasts 800,000 French subscribers.57

QAnon is a hoax, but it has likely even exceeded its creators’ expectations. The online movement about a supposed conspiracy theory controlled by the U.S. deep state has become a global ideology with representation all over the planet. While we might call QAnon a conspiracy theory, some of its adherents consider it to be a movement, whereas others are increasingly calling it a “cult”58 because of its adaptability and how it distorts people’s reality and relationship with their families and society.

There appears to be some debate about the centrality of Trump in some of the international versions of QAnon. For Tristan Mendes, of the University of Paris, “[QAnon] lost its American attachment when it went global, it adapted to the natural context in all the countries where it landed.”59 Yet in French, British, and even Finnish QAnon circles, former President Trump remains the chosen one selected to bring down the global cabal. Graphika “understands” that QAnon offers malicious foreign actors the “ideal delivery mechanism for the seeding of conspiratorial content and blatant disinformation into the politically-engaged US mainstream.”60 Accounts tweeting #WWG1WGA were often pro-Russian accounts. According to the Graphika study, there were only three users responsible for 17,000 tweets; Twitter removed the users as part of their crackdown against suspected Kremlin disinformation operations. Accounts promoting the hashtag #PizzaGate were also affiliated with the (now infamous) Russian Internet Research Agency.61

Russia’s efforts in amplifying QAnon have promoted Vladimir Putin’s primary interest in “Making Russia Great Again” as well as his master plan of undermining democracy in the United States and abroad.62 To be expected, Russian disinformation related to QAnon is replete with anti-Semitism, in particular attacks against philanthropist George Soros. In many ways, Russia’s role in popularizing QAnon in other countries brings our story full circle. Recall, the basis of QAnon myths are anti-Semitic stereotypes from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, originating in Russia 120 years prior, with little change in the tenor or tone in its vilification of Jews.

Hatred of Jews and anti-Semitism connect the European racist political parties with the U.S. far right and their belief about “replacement theory.” From the marchers in Charlottesville in August 2017 to the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol, the fear of replacement brings together the strangest bedfellows. New Yorker war correspondent Luke Mogelson explains what is meant by the “Great Replacement”:

The contention is that Europe and the United States are under siege from nonwhites and non-Christians, and that these groups are incompatible with Western culture, identity, and prosperity. Many white supremacists maintain that the ultimate outcome of the Great Replacement is “white genocide.” In Charlottesville, neo-Nazis chanted, “Jews will not replace us!” . . . and both the New Zealand mosque and El Paso Walmart massacres cited the Great Replacement in their manifestos.63

QAnon is unique compared to many other conspiracy theories or terrorist movements, which we have studied for three decades. This is not simply because of QAnon’s superior ability to absorb and adapt itself to local conditions—Al Qaeda and ISIS were also able to do that. But like apocalyptic terrorist movements, QAnon’s religious zeal and eschatology contend that it is purifying the world of evil. QAnon will redeem a corrupt world and usher in a new golden age. QAnon is like a millenarian sect—a “syncretic political cult, with a basic millenarian structure.”64

One of the more surprising consequences of QAnon has been an unintended backlash against Russia, one of the countries that amplified QAnon content on social media in an attempt to weaken U.S. institutions and erode people’s trust in government and the media. Russian government-backed social media accounts nurtured the QAnon conspiracy theory in its infancy, using bots and sock accounts. “From November 2017 on, QAnon was the single most frequent hashtag tweeted by accounts that Twitter has since identified as Russian-backed, with the term used some 17,000 times.”65

Russian accounts amplified and promoted Pizzagate. Then Russia turned to promoting Tracy Beanz (Diaz) tweeting instructional videos about how to locate Q-drops and posted to her YouTube channel about deciphering the breadcrumb Q-drops with Trump’s tweets or speeches. Russia and China used a variety of contrivances as part of their misinformation toolkit. Russian bots boosted the hashtag #ReleaseTheMemo on Twitter within three months of the birth of QAnon in 2017.66

But Russia now has a QAnon problem of its own. As Silicon Valley de-platformed many QAnon accounts, QAnon shifted to semi-encrypted platforms like Telegram—as had ISIS when it was de-platformed in December 2015. By moving to Telegram, owned by Pavel Durov, it opened the floodgates to a Russian constituency. On both Telegram and Russia’s version of Facebook, VKontakte, QAnon social media posts began flooding account timelines. Groups dedicated to spreading the conspiracy theory in Russian have grown to include tens of thousands of members.67 Like the rest of the globe, Russia is suffering from the COVID-19 pandemic, and economic crises have caused unemployment to reach an eight-year high. Many Russian QAnon members opposed mask mandates and other public health measures while Putin (like Trump) has downplayed the virus but stayed out of public sight for months at a time.68

Russia’s QAnon movement is divided over whether Vladimir Putin is part of the global cabal manipulating world events or, because of his proximity to Trump, an ally behind the scenes. Other QAnon supporters have a hard time believing that Trump has been uniquely chosen to save the children, and as a result Trump’s pivotal role in QAnon narratives is downplayed in Russia.

QAnon Politik

With ample evidence of Russia supporting and amplifying QAnon social media content, it is important to identify the man behind the curtain. Q may not have been directly controlled by Russia, but Russia has been using QAnon to advance its interests. Vladimir Putin has ruled Russia for over 20 years, ever since he was hand-picked by Russia’s first democratically elected president, Boris Yeltsin. In 2020, the Russian constitution was changed to enable Putin to rule for two more consecutive terms (another 16 years), until 2036.69 In April 2021, Putin signed the amendments into law.

Putin’s reign has become famous for the way he constructed a “vertical of power,” with him at the top, and anyone below either heeding his command or suffering the consequences. Twenty years into this effort, it is safe to assume that Russian foreign policy efforts are Putin’s foreign policy efforts. In this sense, QAnon’s spread is a well-executed psyop—a psychological operation to influence “hearts and minds”—a specialty of Putin’s KGB training.

When he became the Russian president, Putin was a political dark horse, barely known to the public. There was a good reason for this anonymity. Putin had been a spy, an officer of the KGB, the Комитет государственной безопасности (Committee for State Security), the notoriously secretive Russian intelligence agency tasked with tracking and tackling both internal and external threats to the ruling system.70 The KGB specialized in psyops to keep tabs on critics of the Soviet ideology. Rumors designed to discredit dangerous opponents and direct the public to actions desired by the Soviet government were a trademark of these psyops.71 With the advent of digital communications, the former KGB, now FSB,72 invested heavily in reorganizing to leverage the informational warfare capabilities provided by the high-speed networks. As part of this effort, Russia established the Internet Research Agency, the troll factory in St. Petersburg.73 Putin’s attempts to destabilize Western democracies and Western-leaning former Soviet republics range from funding divisive political figures (i.e., Marine Le Pen in France74 and Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine75), to sending Agent Provocateurs to foment protests in Germany76 and France,77 to informational warfare such as QAnon.

One study analyzed narratives transmitted by different media backed by the Russian government.78 These included news media officially affiliated with the Russian government (TASS, Russia Today) and with Russia’s presidential administration, but also those radical left- and right-wing resources linked with the “vertical of power” and “patriotic” accounts indirectly connected to Putin—such as the media holdings of Yevgeny Prigozhin (Putin’s friend79 wanted by the FBI for conspiracy to defraud the United States80). The study found all of these diverse sources releasing the same or similar narratives in a highly coordinated manner. The narratives included QAnon content, adapted for the former Soviet or European audiences targeted by these media.

Thus, the “manufactured virus”—that in the American QAnon version originated in a Chinese biolab in Wuhan—in the Russian version originated in a U.S. lab and was brought to China by NATO soldiers. The NATO soldiers are carrying the virus around the world, the narrative explains, because it serves the deep state’s purpose to get rich off the mandated masks and the lockdowns. This story was followed up in the Russian-controlled informational space by fear-mongering stories about the dangers of collaborating with the United States in the area of biochemistry. These follow-up stories supplied a list of “dangerous” laboratories in Ukraine, Georgia, and Kazakhstan––post-Soviet countries that Russia has attempted to bring back under its influence. The nature of the folQlore is the same: Use the real threat of the virus, add to it a sinister component of plotting governments, and point the finger at potential targets of public anger. Only the main characters are recast to better fit the audience’s mindset. The Russian version of QAnon folQlore blames NATO, an organization Putin detests, and directs public fear and outrage at countries that reject Russian control.

Another analysis traced the origins of the Russified QAnon story about the World Health Organization (WHO).81 This narrative claimed the WHO was created by the multi-millionaire Rockefeller, who had survived seven (or eight) heart transplants, for the purpose of running the world, including vaccinations designed to control population growth and destroy people’s individuality. This conspiracy theory—pushed by Russia-backed accounts on Russian-language social media VKontakte, Telegram, and Odnoklassniki, as well as on Facebook and on YouTube—is shrouded in fear-inducing commentary about COVID-19 vaccines and treatments offered through WHO (but, really, by the “world government”).

Clear parallels can be drawn to the U.S. version of the same conspiracy theory. Both narratives fan public distrust in science and fear of vaccines. In marketing this story to Russian-speaking audiences in Europe and in the former Soviet states, Russian “narrative writers” rebranded Wuhan/China (a Russian ally) into WHO (an organization Russia undermines). Instead of Hillary Clinton (a figure of little significance to most Russian speakers) playing a vampire, it is Rockefeller who is painted as barely human, after he had used up seven other people’s hearts, not to mention “Rockefeller” sounds Jewish in Russian, feeding into the anti-Semitic narratives.

The added benefit of manipulating people into distrusting the enemies of the Motherland like NATO and WHO is that conspiracy theories provide a distraction. While the crowd is busy worrying about imaginary dangers and blaming convenient scapegoats, experienced crowd masters are free to reign as they please.

Trained in secrecy and espionage, Putin is rumored to never himself use the Internet, getting his information in papochki—paper folders. He must know better than anyone the dangers lurking online, having masterminded the spinning of a web of lies and reaped its benefits.

Qonclusions

As the many predictions from Q have not seen fruition, there have been diverse reactions from constituents in the United States. We have seen continuously that QAnon keeps moving the goal posts. First Trump was supposed to win the 2020 election. That is why so many QAnon supporters were active in the “Stop the Steal” protests. Then “the Storm” was supposed to be January 6. In some ways the failed insurrection was just that: 1 in 10 people arrested at the Capitol were connected to the QAnon conspiracy theory. The inauguration on January 20, 2021, was supposed to generate “the Storm,” when the cabal would be publicly outed, arrested, and executed. Yet the date passed without any of the predictions coming true. Then March 4, 2021, came and went. March 4 has a complicated explanation, drawing from some of the anti-government militia mythology about the gold standard.

QAnon supporters see the repeated failures of accurately predicting events as less of a deficiency and more of “the sands keep shifting.” They interpret the failed prophecies either by doubling down or assuming, since they did the research themselves, that they got the date wrong. QAnon supporters reiterate: “Trust the plan” and so they continue to support the conspiracy theory even as each prophecy or date goes by without the expected “Storm.”

Part of the problem is that child trafficking is a problem, and certain elements of QAnon myths resonate as being true. In the United States, the arrest and mysterious death of Jeffrey Epstein, and in the UK, the arrest of Jimmy Saville, “demonstrate that elite pedophile rings do exist, and that they do sometimes enjoy protection from powerful political and cultural figures.”82 For true believers, it’s a divine plan. For others it is a social movement. For the people at the top, it is a money grab, and they’ve been getting rich off of selling the conspiracy and exploiting lonely and unhappy people. For evangelicals to continue to believe despite the many disappointments, they need something evangelicals have in great supply: faith. Evangelical pastor and Wheaton College professor Ed Stetzer explains:

People of faith believe there is a divine plan—that there are forces of good and forces of evil at work in the world. . . . QAnon is a train that runs on the tracks that religion has already put in place.83

When Q stopped posting drops in the aftermath of the 2020 election (December 2020), some of the better-known Q influencers stepped in to take control. Recall, these are the influencers who have benefited the most from the financial support of QAnon believers or from selling merchandise or profiting from increased traffic to their websites.

Whatever happens to QAnon in the United States, as long as the Republican Party does not disavow it, it will not completely disappear. QAnon has seeped into the religious sphere, the political sphere, and the international sphere; we will be dealing with the challenges associated with QAnon for years to come.