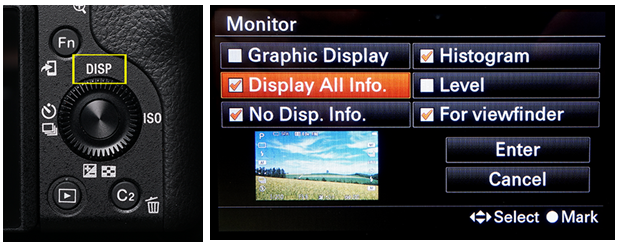

Figure 3-14: You can choose which displays the DISP button cycles through via this screen. (And you can configure the camera to cycle through different screens depending on whether you’re looking at the LCD (“Monitor”) or EVF (“Finder”).

|

Figure 3-14: You can choose which displays the DISP button cycles through via this screen. (And you can configure the camera to cycle through different screens depending on whether you’re looking at the LCD (“Monitor”) or EVF (“Finder”). |

When you press the DISP button (the UP arrow button on the rear control wheel Figure 3-14a) multiple times, the camera will cycle through the displays you have checked in Menu -->  2 --> DISP Button --> [Monitor or Finder].

2 --> DISP Button --> [Monitor or Finder].

When you go to this screen you can scroll amongst the options and a small preview will appear in the lower-right-hand corner. You can select and unselect the screens you want using the center button.

Figure 3-15: The display screens available. Pressing the DISP button switches from one screen to another. |

When you go there make sure “Histogram” is checked as an option (Figure 3-14b). This is the ONLY display option available that shows you a live histogram as you’re composing so you can know if you’re blowing out any highlights (or losing detail in your shadows). (Histograms are explained in Appendix A, in Section A.7.)

Video options can be pretty daunting, and so I'm leaving the very heavy technical stuff to Chapter 12. In the meantime, here's the bare minimum you need to know about shooting video, starting with the point-and-shoot auto-everything home movie mode:

8 --> MOVIE Button is set to ALWAYS). (Or, if you’re like me, you’ve reassigned C1 to be “MOVIE”.) To stop taking movies, push that red button again.

8 --> MOVIE Button is set to ALWAYS). (Or, if you’re like me, you’ve reassigned C1 to be “MOVIE”.) To stop taking movies, push that red button again. ), then you can specify the P/A/S/M equivalent for movies you shoot via MENU -->

), then you can specify the P/A/S/M equivalent for movies you shoot via MENU -->  7 --> Movie / HFR and choose the desired mode. (Section 6.39). With the exposure mode dial set to “Movie”, Live View automatically switches to the appropriate aspect ratio (either 16:9 or “Super35”) so you can compose your shot beforehand.

7 --> Movie / HFR and choose the desired mode. (Section 6.39). With the exposure mode dial set to “Movie”, Live View automatically switches to the appropriate aspect ratio (either 16:9 or “Super35”) so you can compose your shot beforehand.  3 --> Focus Area setting) will work in movie mode except for the last item – Lock on AF won’t be a selectable option.

3 --> Focus Area setting) will work in movie mode except for the last item – Lock on AF won’t be a selectable option. 8 --> MOVIE Button is set to Movie Mode Only. In this configuration, if you want to take a movie you must move the exposure mode dial to Movie position first. (Then if you want to take pictures you’ll have to move it to something else.)

8 --> MOVIE Button is set to Movie Mode Only. In this configuration, if you want to take a movie you must move the exposure mode dial to Movie position first. (Then if you want to take pictures you’ll have to move it to something else.)

TIP: While shooting movies you can focus-lock using the currently selected focus area by pressing the shutter release button halfway. The focus will remain locked until you take your finger off the shutter release. So it’s a quick way to go from the mandatory AF-C to AF-S while shooting. |

TIP: This camera has a clip length limitation – 2 GB file size for AVCHD movies; 4 GB for XAVC S. If you’re shooting in .mp4 video mode (more on that later), then the camera automatically stops shooting when it hits this limit. If on the other hand you’re shooting in AVCHD video mode, then the camera will “close” the first file and automatically start recording a new one while you shoot. The only thing for you to do is edit the two clips together using programs such as PlayMemories Home. |

“Center Lock-On AF” is the 2nd of two features that allows the camera to track a subject. And unlike the other object tracking feature "Lock-on AF" (Section 6.15.6), this one works when shooting video, too. (This can be a valuable feature since the other great object-recognition feature, Face Recognition, doesn't work in video.)

For best results, take care that your object is distinctly colored relative to its surroundings, for this feature actually is tracking color rather than any particular shape or feature. Here’s how to use it:

|

Figure 3-16: You can tell your camera “Here, track this!” via the center button of the multi-selector and it will track the object across the screen. |

3 --> Focus Area --> [Choose anything except the last option]).

3 --> Focus Area --> [Choose anything except the last option]). 7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> Center Button is set to Focus Standard.

7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> Center Button is set to Focus Standard. 6 --> Center Lock-On AF --> On. The top screen in Figure 3-16 is seen.

6 --> Center Lock-On AF --> On. The top screen in Figure 3-16 is seen. Things to note:

Overall, although it’s useful when it works, I’d say it’s best not to expect too much from this feature. I’ve found that even if the subject moves slowly the camera can get confused and select something else as the subject instead of what you specified. (Don’t judge its abilities too harshly – it’s a difficult feat to perform.)

I have found this feature to be most useful when shooting home movies – I just focus on my subject and the camera will do a better job focus tracking on a moving subject than if the feature were off.

TIP: There’s a slightly better implementation of this feature which doesn’t require you pressing several buttons to invoke it, and your subject doesn’t necessarily have to be in the center. It’s the 6th Focus Area option “Lock-On AF” and it’s described in Section 6.15.5. (It doesn't work when shooting videos, though.) |

|

Figure 3-17: Sweep Panorama mode. |

Panorama shots aren’t as novel as they once were, but that doesn't make them any less fun or easy. So to get started, turn your exposure mode dial to “Sweep Panorama” (Figure 3-17). Then perform the following:

|

Figure 3-18: A sample Sweep Panorama shot. Your camera makes these kinds of shots ridiculously easy. No tripod nor home computer is required. |

|

Figure 3-19: Need different aspect ratio? Set Sweep Panorama to “Down”, rotate your camera counterclockwise 90 degrees, and sweep from left to right to get an image that looks more like a 16:9 shot and less like a panorama. |

If you have your panorama mode set to Wide (which means “wider than ‘Standard’” -- Make sure the function dial is set to Panorama and then MENU -->  1 --> Panorama: Size --> Wide), what you get is a high-resolution panorama picture – 12,416 pixels x 1,856 pixels ( Figure 3-18). Most impressive! (Interestingly, these are the same dimensions as what Sony’s other cameras produced – the number of megapixels doesn’t affect the panorama size, apparently.)

1 --> Panorama: Size --> Wide), what you get is a high-resolution panorama picture – 12,416 pixels x 1,856 pixels ( Figure 3-18). Most impressive! (Interestingly, these are the same dimensions as what Sony’s other cameras produced – the number of megapixels doesn’t affect the panorama size, apparently.)

There’s much more to say about the Panorama features – and I’ll continue this subject in Section 6.4.

TIP 1: The histogram is not displayed during panorama shooting. Probably because it can’t know what the camera will be pointing at at the end of the sequence. TIP 2: If you’re very serious about panoramas, it is better to do things the old fashioned way: Use a tripod, shoot a sequence of overlapping images in RAW, stitch them together in photoshop or lightroom. Now only will you have the advantage of using RAW’s wider dynamic range, but you’ll also get a SIGNIFICANTLY larger file which can be blown up to auditorium-wall size. |

If you like the idea of remote control, there are three options available to you: The ability to control your camera with your Wi-Fi-equipped smartphone (discussed in detail in Chapter 5), an infrared remote control (The Sony RMT-DSLR2), and a new plug-in cable release ideal for time exposures called the RM-VPR1 (Figure 3-20.)

Figure 3-20: You can use your Wi-Fi-enabled smartphone as a remote control (and remote viewfinder) for your camera – as you can see it captured quite an expression on the test subject (left). There’s also an IR remote (center) and a new wired option (right) which plugs into the camera's USB port. TIP: If your Android smartphone has an infrared transmitter (my Galaxy S5 does), there's a FREE app that lets you control Sony cameras remotely. It's called ShutterBOT (http://bit.ly/1PeoH62 ). If you have a Samsung phone then the capability is already there in a pre-loaded app called Samsung IR Universal Remote. |

|

|

Figure 3-21: The “Images Remaining Counter” (yellow rectangle) is only a guess, since the size of a .jpg depends on its content. |

When the camera shows you how many more images you can shoot on the memory card (yellow rectangle in Figure 3-21), it’s only a guess -- the actual size of a .jpg image can vary wildly based on the content of the image. (Chapter 15 will explain why.) So don’t take this number literally.

TIP: Interestingly, the camera doesn’t take the currently-set aspect ratio into account when making its images-remaining calculation. Files shot in 16:9 aspect ratio take up less room on your memory card than the standard 3:2 (at least JPGs do); yet the camera will show the same number of images remaining for both settings. |

Figure 3-22: When a full-frame lens Is projected onto an APS-C Sized sensor, very little of the what the lens sees is captured by the sensor. |

Okay, this will be a short section. Sony Alpha cameras have two kinds of lens mounts: A-mount, which they inherited from Minolta, and the E-mount for mirrorless cameras. (Yours is an E-mount.) And there are two kinds of E-mount lenses: those made for APS-C sized sensors (like your A6300) which have the “E” designation, and those made for Full Frame cameras like the A7 series, which have the “FE” designation.

As Figure 3-22 demonstrates, attaching a full-frame FE lens to a small-sensor body like the A6300 results in a lot of wastedness: very little of the scene gets capture, plus the lens is bigger and heavier (and more expensive) than it needs to be. So FE lenses are not a good fit (figuratively).

Have something other than a native E-mount lens? You can use an adapter to attach just about every kind out there. I talk about lens adapters in the next chapter.

Sony and Zeiss Brands

Both Sony and Zeiss make native autofocusing lenses for the E-mount. Sony offers a high-end “G” series lens, and as of recently have introduced an even higher-end lens line called “G-master” which is designed for the next generation of high-resolution, full-frame sensors. Lenses that are not labeled as either “G” or “G Master” are no slouch either – and they are also lightweight and more affordable, and will be a good match for the A6300.

Zeiss, a partner with Sony, also has several lines of lenses which are designed for the E-mount. Usually they have the term "ZA" somewhere in the lens name. All of these lenses had designs approved by Zeiss, and are using Zeiss manufacturing hardware for precision quality control, and are made either by Sony or Zeiss.

Here’s a rundown on the Zeiss brands and what they stand for:

For a complete, up-to-date list of all available E-mount lenses made for the APS-C format cameras from multiple manufacturers, visit Brian Smith’s constantly-updated website at http://briansmith.com/aps-e-mount-lenses-for-sony-mirrorless-cameras/ .

Although it’s hard to find, the A6300 has what’s called a Diopter Correction element to the right of the EVF (Figure 3-23).

The most basic kinds of eyesight disorders are nearsightedness (Myopia) and farsightedness (Hyperopia), and if that’s all you have (and if you only have a mild to moderate case of it) then your camera can provide a correction for you so you need not wear your eyeglasses while shooting. Correction for such disorders are commonly measured in units called diopters; and the number of diopters in your prescription represents the amount of correction needed to provide 20/20 vision.

Figure 3-23: The diopter correction wheel can apply basic eyesight corrections for some eyeglass wearers. Sony has dispensed with any kind of calibration markings, so you’ll just have to turn the wheel until a menu screen looks sharpest to you. |

Interestingly, all camera viewfinders have a built-in optic that makes the focusing screen (which is physically very close) appear to be very far away, allowing your eye to focus to infinity. You can verify this for yourself: set the zoom lens on your lens to around 58mm focal length, and look at your subject with BOTH EYES open (one looking through the EVF, the other looking over the “shoulder” of the pseudo-pentaprism hump). The images from both eyes should appear in focus. This means that if you’re farsighted, you really shouldn’t need any diopter correction at all in your viewfinder.

So the EVF has a mechanism built in that can provide diopter correction mostly to help nearsighted folks. The correction ranges from -3 (nearsightedness) to +1 (slight farsightedness). To adjust it, perform the following:

Note that if you have more than a mild astigmatism (another common disorder that can’t be corrected using simple “spherical” optics), the built-in diopter correction will probably not make things look clearer to you. You'll need to use the camera with your eyeglasses on instead.