Kṛṣṇa is one of the most captivating and beloved of Hindu deities, whose divine exploits are celebrated in all parts of India in devotional poetry, scriptures, theological works, visual arts, pilgrimage traditions, dramatic performances, and an array of other cultural forms.1 The Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the authoritative scripture of Vaiṣṇava bhakti, recounts the divine drama through which Kṛṣṇa, the supreme Godhead, descends to earth at the end of Dvāpara Yuga in approximately 3000 BCE and unfolds his līlā, divine play, in the region of Vraja in North India.2 Kṛṣṇa is born in the city of Mathurā as a prince of the Yādava clan known as Vāsudeva, the son of Vasudeva and Devakī. He is born in a prison where his parents have been confined since their wedding day by his evil uncle, King Kaṃsa, because during their nuptial festivities Kaṃsa had heard an incorporeal voice prophesying that he would be slain by the couple’s eighth child. Immediately after his birth Kṛṣṇa reveals his resplendent four-armed divine form to his parents and then resumes his appearance as an ordinary infant. Through his yoga-māyā, power of illusion, he loosens the chains of Vasudeva and causes the prison guards to fall asleep. In order to protect his newborn son from death at Kaṃsa’s hands, Vasudeva then carries Kṛṣṇa across the Yamunā River to a nomadic cowherd encampment and places him in the care of the cowherd Nanda and his wife Yaśodā, who raise him as their son.

The core narrative of the tenth book of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa focuses on the first sixteen years of Kṛṣṇa’s life as Gopāla Kṛṣṇa, in which he carries out his līlā in the form of a gopa, cowherd boy, in the land of Vraja (Vraja-bhū), the pastoral arena outside of the city of Mathurā, where he engages in playful exploits with his companions, the cowherds (gopas), cowmaidens (gopīs), and cows (gos) of Vraja. At the end of his extended sojourn in Vraja, Kṛṣṇa is portrayed as returning to Mathurā, the city of his birth, where he assumes his princely mantle as Vāsudeva and accomplishes his divine mission of killing his evil uncle Kaṃsa. He then establishes his kingdom in Dvārakā, where he rules as Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa, the chief of the Yādava clan. It is in his royal status as the prince of the Yādavas that Kṛṣṇa serves as the charioteer of Arjuna in the Mahābhārata war and proclaims to him the wisdom of the Bhagavad-Gītā.

Whereas Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa is represented in the Bhagavad-Gītā as the wise, somber teacher who is the upholder of dharma, the cosmic ordering principle that maintains the harmonious functioning of the social and cosmic realms, Gopāla Kṛṣṇa is represented in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as the master of līlā, divine play, who during his sojourn in Vraja delights in pranks and lovemaking, overturning the norms of the social order with unrestrained exuberance while at the same time maintaining the cosmic order by effortlessly disposing of numerous demons who torment the people of Vraja. He is the divine trickster and the divine lover who lures his companions, the gopas and gopīs of Vraja, with the sound of his flute, bewitching and intoxicating them, inspiring them to break the boundaries of social convention and join with him in his play. In his youthful exploits as the cowherd of Vraja, Gopāla Kṛṣṇa is celebrated as the mischievous child of his foster parents Nanda and Yaśodā, the cherished friend of the cowherd boys, the passionate lover of the cowmaidens, and the heroic protector of all the people of Vraja.

The land of Vraja in North India is thus celebrated as the sacred terrain where Kṛṣṇa, during his sojourn on earth, romped through the hills and forests, danced in the groves, and bathed in the rivers and ponds. He is held to have left his imprint—literally—on the entire landscape in the form of his footprints and other bodily traces that mark the līlā-sthalas, the sites of his playful exploits. Among the earliest known religious authorities to visit Vraja and perform pilgrimages in the area are seminal figures in two of the most important Vaiṣṇava sampradāyas (schools): Caitanya (1486–1533 CE), who inspired the establishment of the Gauḍīya Sampradāya, and Vallabha (1479–1531 CE), who founded the Vallabha Sampradāya, or Puṣṭi Mārga. Caitanya and Vallabha subsequently directed their followers—the early Gauḍīya authorities known as the “six Gosvāmins of Vṛndāvana” and the leaders of the Puṣṭi Mārga—to “rediscover” and restore the “lost” līlā-sthalas where particular episodes of Kṛṣṇa’s līlā occurred and to establish temples and shrines to visibly mark these sites as tīrthas, sacred sites. In accordance with the directives of their teachers, the leaders of the Gauḍīya Sampradāya and the Puṣṭi Mārga mapped the narratives of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and other authoritative Sanskritic scriptures onto the landscape of Vraja, transforming the geographic region into a pilgrimage place interwoven with tīrthas identifying the sites of Kṛṣṇa’s līlā activities.3

From the end of the sixteenth century CE to the present day, millions of pilgrims have traveled to Vraja—or to “Braj,” the Hindi designation by which the “Vraja” of the Sanskritic scriptures is known today—from all regions of India to track the footprints of Kṛṣṇa and to recall the stories of his youthful exploits that are indelibly associated with this place. Vraja is represented as a maṇḍala, or circle, formed by an encompassing pilgrimage circuit called the Vana-Yātrā (Hindi Ban-Yātrā), which was established in the sixteenth century and is schematized as a circular journey through twelve forests that is traditionally calculated to be eighty-four krośas,4 or approximately 168 miles. Pilgrims come from all over India each year to perform the Vana-Yātrā, arriving via trains, buses, and automobiles as well as on rickshaws, bullock carts, horse carts, and by foot. After inaugurating their pilgrimage with a ritual bath in the sacred waters of the Yamunā River, they traditionally embark on the parikrama (circumambulation) path that encircles the entire region of Vraja with bare feet as a sign of their reverence for the dust that has been consecrated by the feet of Kṛṣṇa. As part of the Vana-Yātrā, the full circumambulation of Vraja, which generally lasts from one to two months, they may also traverse the three smaller pilgrimage circuits within the encompassing circuit, circumambulating the city of Mathurā, Mount Govardhana, and the town of Vṛndāvana as they reach each of these central nodes along the Vana-Yātrā path. Since the establishment of these pilgrimage networks in the sixteenth century, local residents of Vraja have also undertaken their own pilgrimages periodically throughout the year, walking around one or more of the parikrama paths at Mathurā, Govardhana, and Vṛndāvana.

As pilgrims and local residents journey through the landscape of Vraja, they move from līlā-sthala to līlā-sthala, celebrating the particular episodes of Kṛṣṇa’s līlā that are associated with each geographic locale. They visit the hills, forests, groves, ponds, and other sites where he is said to have engaged in his playful exploits and left behind his bodily traces. They revel in Kṛṣṇa’s bodily presence in the sacred terrain of Vraja with their own bodies, embracing the ground through full-body prostrations, rolling in and ingesting the dust, touching the stones, hugging the trees, bathing in the ponds—engaging with their bodies every part of the landscape consecrated by the body of the divine cowherd. Moreover, as David Haberman has emphasized, many contemporary pilgrims and residents of Vraja proclaim that “Vraja is the body of Kṛṣṇa,” echoing the pronouncement of Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭa, the sixteenth-century Gauḍīya authority who is credited with creating the Vana-Yātrā.5

Kṛṣṇa’s corporeal instantiation in the land of Vraja is particularly evident in pilgrimage traditions associated with Mount Govardhana. Kṛṣṇa is represented in one līlā episode in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as assuming the form (rūpa) of Mount Govardhana and in his mountain form consuming the ritual offerings that the cowherds had originally intended for the deity Indra. When Indra retaliated by unleashing torrential rains to punish the people of Vraja for ceasing to worship him, Kṛṣṇa in his cowherd form effortlessly uprooted the mountain and held it aloft with one hand as an umbrella for seven days in order to protect the cowherds, cowmaidens, and cows of Vraja from Indra’s deluge.6 Evoking this tradition, many contemporary pilgrims and local residents revere Govardhana as a localized embodiment of Kṛṣṇa in the form of a mountain—even though, according to several narratives that are traditionally recounted about Govardhana, this once vast mountain has now been reduced to the size of a modest seven-mile-long hill due to the curse of a sage.7 Because they venerate Mount Govardhana as the body of Kṛṣṇa, they may refuse to set foot on the sacred mountain lest they desecrate the divine body—a tradition that is held to have been established by Caitanya during his sixteenth-century pilgrimage to Vraja.8 Instead they circumambulate the mountain by foot, traversing the Govardhana parikrama path—which is calculated to be seven krośas, or approximately fourteen miles—in a minimum of five to six hours if walking at a brisk pace. Some pilgrims and residents of Vraja, out of reverence for Kṛṣṇa’s mountain form, circumambulate the mountain in a manner called daṇḍavat-parikrama, which involves performing a sequence of full-body prostrations along the parikrama path—a practice that can take ten to twelve days if performed along the entire length of the pilgrimage circuit. This practice is particularly prevalent during the festival known as Govardhana Pūjā, or Annakūṭa, which is celebrated each year on the day after Dīvālī, the festival of lights, in the month of Kārttika (October–November). As part of their veneration of Mount Govardhana during the festival, pilgrims and local residents traditionally perform daṇḍavat-parikrama along the parikrama path until they reach the town of Jatīpurā at the foot of the mountain. In Jatīpurā a great feast is celebrated in which the mountain, as a form of Kṛṣṇa, is ritually anointed with milk, decorated with auspicious red and yellow powders, and offered a “mountain of food” (anna-kūṭa).9

Mount Govardhana’s special status as a localized embodiment of Kṛṣṇa is ascribed not only to the mountain as a whole but also to each of its stones, or śilās—a tradition that is held to derive from Caitanya.10 In contrast to sculpted iconic images, mūrtis or arcās, which are fashioned by artisans and must be consecrated by brahmin priests through rites of installation (pratiṣṭhā) in order to invest the image with the deity’s presence, Govardhana śilās are worshiped as natural forms (svarūpas) of Kṛṣṇa and therefore do not require ritual installation. These aniconic mūrtis are venerated by pilgrims and residents of Vraja as living forms of the deity and are worshiped regularly through pūjā, ritual offerings, in public and domestic shrines throughout Vraja.

Kṛṣṇa’s bodily instantiations in Vraja are not limited to Govardhana śilās, Mount Govardhana as a whole, or the entire sacred geography of Vraja. Kṛṣṇa is also held to be embodied in a multiform array of particularized mūrtis, ritual images, that are worshiped in the myriad temples that dot the landscape of Vraja. The most revered among the mūrtis in Vraja are those that are considered svayam-prakaṭa, “self-manifested” by Kṛṣṇa himself. These self-manifested mūrtis are venerated as Kṛṣṇa’s living bodies in which his real presence spontaneously dwells, and thus, in contrast to sculpted images fashioned by artisans, they do not require rites of installation. The central mūrti of the Puṣṭi Mārga, for example, is the self-manifested Śrī Nāthajī, a black stone image of Kṛṣṇa with his left arm held aloft as upholder of Mount Govardhana, which is held to have progressively revealed itself in the fifteenth century CE by emerging from the ground in stages on the top of the mountain.11 Among the central mūrtis of the Gauḍīya Sampradāya are two svayam-prakaṭa mūrtis that Kṛṣṇa is held to have manifested to two of the early Gauḍīya authorities who were immediate followers of Caitanya, appearing in his two-armed cowherd form in the emblematic tribhaṅga posture that he adopts when playing the flute in which his body is “bent in three places.” The first, a black stone image of the flute-playing Kṛṣṇa as Govindadeva, the keeper of cows, is celebrated as revealing itself to Rūpa Gosvāmin in 1533 or 1534 CE at the site of the original yoga-pīṭha, “seat of union,” in Vṛndāvana where Kṛṣṇa enjoyed his nightly trysts with Rādhā, his favorite gopī, cowmaiden lover.12 The second, a small black stone image of the flute-playing cowherd as Rādhāramaṇa, the beloved of Rādhā, is held to have appeared to Gopāla Bhaṭṭa Gosvāmin in 1542 CE out of a śālagrāma stone that he was worshiping in Vṛndāvana.13

Rādhāramaṇa is unique among these svayam-prakaṭa mūrtis of Kṛṣṇa—as well as among the other mūrtis established by the six Gosvāmins—in that it is the only mūrti that was not removed from Vraja and taken to a safer locale in response to the iconoclastic attacks of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707 CE) in the latter half of the seventeenth century CE. Rādhāramaṇa is thus allotted a special place in the history of Vraja as one of the oldest and most important of the mūrtis of Kṛṣṇa, for the image has been continuously worshiped in Vṛndāvana for over 470 years by the lineage of priests of the Rādhāramaṇa temple who claim direct descent from Gopāla Bhaṭṭa Gosvāmin through his first householder disciple, Dāmodara Gosvāmin.

If we venture into the Rādhāramaṇa temple today, we find that the logic of the daily temple service, like that found in other Kṛṣṇa temples throughout Vraja, involves venerating the mūrti as the living body of Kṛṣṇa on two levels that reflect the “double life” of the deity. On the one hand, the priests of the temple celebrate the public life of Rādhāramaṇa as the embodiment of aiśvarya, divine majesty, by honoring and serving him as a royal guest in the temple in strict accordance with the ritual and aesthetic prescriptions of mūrti-sevā. Each day the deity embodied in the mūrti is awakened, bathed, dressed, adorned with jewelry and flowers, fed periodic meals, revered through ritual offerings, and put to bed. Worship of the mūrti involves the presentation of a series of sixteen ritual offerings (upacāras), including food, water, cloth, sandalwood paste, flowers, tulasī leaves, incense, and performance of āratī through circling oil-lamps before the image. On the other hand, the temple priests seek to foster an awareness of the hidden life of Rādhāramaṇa as the embodiment of mādhurya, divine sweetness, by dividing the temple service into eight periods (aṣṭa-yāma) corresponding to the aṣṭa-kālīya-līlā, the eight periods of the divine cowherd’s daily līlā that goes on eternally in his transcendent abode and its earthly counterpart, the land of Vraja.14 During this eightfold līlā he engages in intimate love-play in the secret bowers with his cowmaiden lover Rādhā, tends the cows and romps through the forest with his cowherd buddies, and returns home periodically to be bathed, dressed, and fed by his adoring foster mother, Yaśodā.15

Pilgrims and local residents flock to Rādhāramaṇa temple throughout the day, eager to participate in one or more of the eight temple services—from maṅgala āratī, the early morning service that is held before dawn when Rādhāramaṇa is awakened, to śayana āratī, the final service of the day that is held around 9:00 PM just before he retires to his bedchamber in the inner sanctum of the temple. They come to receive darśana of Rādhāramaṇa, to see and be seen by the deity embodied in the mūrti, and to partake of prasāda, the remnants of food and other offerings that have been suffused with his blessings. They engage Kṛṣṇa’s embodied form in the mūrti with their own bodies, circumambulating the inner sanctum, prostrating before the mūrti, making offerings, singing, dancing, blowing horns, sounding gongs, ringing bells, and beating drums in exuberant celebration. Through līlā-kīrtana, singing the praises of Kṛṣṇa and extolling his līlā activities, worshipers hope to penetrate beyond the sight of Kṛṣṇa’s manifest form as the black stone mūrti to a visionary experience of his hidden presence in and beyond the mūrti, culminating in direct realization of the divine cowherd’s unmanifest līlā that goes on eternally in his transcendent abode and its immanent counterpart, the land of Vraja.

Periodically during the daily temple service in Rādhāramaṇa temple, as well as in other Gauḍīya temples in Vraja, the sounds of nāma-kīrtana or nāma-saṃkīrtana, communal singing of the divine names of Kṛṣṇa, can be heard resounding throughout the temple. According to the Gauḍīya theology of the name that is ascribed to Caitanya himself, Kṛṣṇa’s nāmans, divine names, are his localized embodiments in the form of sound, just as his mūrtis are his localized embodiments in the form of ritual images. In this perspective singing the divine names serves as a means through which worshipers enliven Kṛṣṇa’s divine presence and send forth his reverberating sound-forms as offerings to his sumptuously adorned image-form. The sounds of nāma-saṃkīrtana are not confined to temple spaces but can be heard throughout Vraja, as kīrtana troupes process through the streets of Vṛndāvana and pilgrims traverse the parikrama paths singing the names of Kṛṣṇa.16

Kṛṣṇa’s instantiation in sound extends beyond the seed-syllables that constitute his nāmans to the recited narratives of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, which is revered as his text-embodiment in the form of speech. Pilgrims and residents of Vraja engage Kṛṣṇa’s living presence in the oral-aural text through hearing recitations of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa by qualified brahmin reciters as part of the daily service in local temples and through attending public performances of Bhāgavata saptāha in which all twelve books of the Bhāgavata are ritually recited, from beginning to end, over the course of seven days. The Bhāgavata Purāṇa is not only revered as a body of efficacious sounds that when recited manifest Kṛṣṇa’s presence among the listeners; it is also extolled as a wellspring of multilayered meanings that when expounded serve to illuminate the nature of the supreme Godhead and his līlā. Temples in Vraja occasionally sponsor seven-day Bhāgavata celebrations that combine Bhāgavata saptāha, in which 108 brahmins recite together one-seventh of the text each morning, and saptāha kathā, in which a learned Bhāgavata scholar delivers a discourse on the recited portion of the Bhāgavata each afternoon or evening, expounding the meaning of the Sanskrit text in a vernacular language appropriate for the particular audience.17 In addition to these oral-aural modes of reception, worshipers in Vraja also engage the Bhāgavata in its written-visual form by ritually venerating the concrete book, which is enshrined in a number of local temples as a special kind of mūrti.18

During the monsoon season (July–August) every year thousands of pilgrims travel to Vraja from all over India to participate in Kṛṣṇa’s līlā not only through hearing the stories of his divine play as recounted in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and other authoritative texts but also through seeing these stories enacted in dramatic performances called rāsa-līlās. The rāsa-līlā is traditionally performed by rāsa-līlā troupes in which young brahmin boys native to Vraja enact the roles of Kṛṣṇa, Rādhā, the gopīs, and the other characters in Kṛṣṇa’s līlā. As soon as the central actors don their crowns as Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā and the performance commences, they are revered during the duration of the performance as svarūpas, living forms, of the deity and his eternal consort. Rāsa-līlā performances are divided into two parts. The first part, the rāsa section, enacts Kṛṣṇa’s eternal circle dance (nitya rāsa) with Rādhā and the other gopīs that takes place perpetually in the unmanifest līlā in his transcendent abode beyond the material realm. The second part, the līlā section, varies in content from day to day and enacts one of the specific episodes of Kṛṣṇa’s manifest līlā that occurred during his sojourn on earth in the land of Vraja. During the period that separates the rāsa section from the līlā section of the performance, a tableau is formed in which the actors who embody Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā are enthroned on a dais and members of the audience come forward to receive their darśana and make offerings to the svarūpas as living mūrtis.19

How are we to understand the manifold ways in which Kṛṣṇa’s bodily presence—in stones, in a mountain, in an entire landscape, in temple images, in divine names, in a sacred text, in young male actors—has been invoked, encountered, engaged, and experienced through the bodily practices of Kṛṣṇa bhaktas, not only in Vraja but also in devotional communities throughout the Indian subcontinent and the diaspora? In this study I will interrogate the logic of embodiment that is integral to bhakti traditions and will seek to illuminate more specifically the multileveled models of embodiment and systems of bodily practices through which devotional bodies are constituted in relation to divine bodies in Kṛṣṇa bhakti traditions. I will ground my general reflections on bhakti and embodiment in an analysis of discourses of Kṛṣṇa bhakti, focusing in particular on two case studies: the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the authoritative scripture of Kṛṣṇa bhakti; and the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava tradition inspired by Caitanya in the sixteenth century, which invokes the canonical authority of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as the basis for its distinctive teachings.

In order to provide a broader theoretical framework for my study, I will briefly survey certain trends of scholarship on the body in the social sciences and humanities that have had a significant impact on studies of the body in religion. I will then map out an array of Hindu formulations of the body and will argue that a sustained investigation of these formulations can contribute in important ways to theories of embodiment and also to illuminating the connections between constructions of embodiment and notions of the person and the self. Finally, I will turn to an analysis of the role of embodiment in Hindu bhakti traditions and more specifically Kṛṣṇa bhakti traditions, which is the central concern of my study.

Theorizing the Body in the Human Sciences

In the past decades there has been an explosion of interest in the “body” as an analytical category in the social sciences and humanities, particularly within the context of cultural studies. Studies of the body have proliferated, representing a range of disciplinary perspectives, including philosophy, anthropology, sociology, history, psychology, linguistics, literary theory, art history, and feminist and gender studies. In attempting to demarcate their respective methodological approaches, scholars speak of the phenomenology of the body, the anthropology of the body, the sociology of the body, the biopolitics of the body, the history of the body, thinking through the body, writing the body, ritualizing the body, and so on. Since the 1990s a number of scholars of religion have begun to reflect critically on the notion of embodiment and to examine discourses of the body in particular religious traditions. Among the plethora of perspectives and theories, three areas of scholarship in particular have had a significant influence on studies of the body in religion: the body in philosophy, the body in social theory, and the body in feminist and gender studies.

The growing importance of the body in philosophy is closely tied to critiques of the hierarchical dichotomies fostered by Cartesian dualism and objectivism: mind/body, spirit/matter, reason/emotion, subject/object. One trend of critical analysis stems from the philosophical phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who sought to overcome the dualities of subject/object and mind/body by positing the notion of the lived body based on a continuum of consciousness-body-world. Merleau-Ponty’s theory of embodiment has had a significant impact beyond the domain of philosophy, particularly in the areas of phenomenological psychology, phenomenological anthropology, and phenomenological sociology.20 Such studies tend to emphasize the role of the lived body as the phenomenological basis for experience of the self, world, and society.

A second trend of analysis focuses more specifically on critiques of the mind/body dichotomy in which the disembodied mind reigns over and above the mind-less body. A number of studies have suggested that the relationship between the mind and body needs to be reevaluated and the model of hierarchical dualism jettisoned for a more integrated model of mutual interpenetration: the mindful body, alternatively characterized as the “mind-in-the-body,” “embodied mind,” or “body-in-the-mind.”21 Critiques of the mind/body dichotomy constitute an integral part of studies of the body not only in philosophy but also in other fields.22

While theories concerned with the phenomenology of the body emphasize the lived experience of the body-self, social theories that seek to develop an anthropology of the body or sociology of the body are generally founded on the assumption that the body is a social construction rather than a naturally given datum. Such theories involve an analysis and critique of the discursive practices that constitute and inscribe the social body and the body politic. These theories emphasize, moreover, that the body has a history, and thus one aspect of the social theorist’s task is to reconstruct the history of the body and its cultural formations.

Among the various theoretical perspectives on the body developed by anthropologists, sociologists, and historians, three types of approach are central. The first approach focuses on the body as a symbolic system that conveys social and cultural meanings. This approach builds upon the insights of Mary Douglas, whose work on the symbolism of the body emphasizes the dialectical relation between the physical body and the social body. A second trend of analysis is concerned primarily with the body as the locus of social practices. Among the theoretical bases of this approach are Marcel Mauss’s conception of “techniques of the body” and Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of the “socially informed body” as the principle that generates and unites all practices. A third approach focuses on the body as a site of sociopolitical control on which are inscribed relations of power. This approach builds upon the seminal contributions of Michel Foucault, applying and extending his conception of the “biopolitics of power” through which the body is regulated, disciplined, controlled, and inscribed.23

Following the lead of Foucault, a number of social theorists have sought to chronicle the history of the body, its representations, and its modes of construction.24 This has resulted in a variety of specialized studies focused on particular types of embodiment and the discursive practices that contribute to their formation. Among the different categories of the body singled out for attention by social theorists are the sexual body, the alimentary body, and the medical body. The sexual body is constituted by sexual norms and practices, including models of sexual difference, rules and techniques regulating sexual intercourse, codes of sexual restraint and decorum, traditions of celibacy and asceticism, and reproductive regulations and technologies.25 The alimentary body is constituted by food practices and dietary regulations, including taxonomies classifying types of food substances, laws regulating the preparation, exchange, and consumption of food, norms of table fellowship and etiquette, practices of fasting and control of food intake, and dietetic management.26 The medical body is constituted by medical discourses and practices, including taxonomies delineating categories of diseases, classifications of human bodies in terms of physical body types and pathologies, theodicies of illness and pain, traditional methods of healing and medicine, and modern medical technologies and regimens.27

The Body in Feminist and Gender Studies

The body is also a central focus of analysis and cultural critique in feminist and gender studies. Feminist critiques of the “phallocentric” discourses of Western culture generally involve a sustained critique of the dualisms fostered by these discourses, with particular attention to the gendered inflection of the mind/body dichotomy. The distinction between mind and body, spirit and matter, in its various formulations in Western philosophy from Plato and Aristotle to Descartes, is a hierarchical and gendered dichotomy: the mind, characterized as the nonmaterial abode of reason and consciousness, is correlated with the male and is relegated to a position of superiority over the body, which is characterized as the material abode of nonrational and appetitive functions and is correlated with the female. Thus one aspect of the feminist project involves challenging the tyranny of male:reason by re-visioning the female:body and ultimately dismantling the dualisms that sustain asymmetrical relations of power.

Among the wide range of perspectives on the body in feminist and gender studies,28 four types of approaches are of particular significance. One trend of analysis, consonant with early American feminists’ emphasis on the irreducible reality of women’s experience, centers on experiences of the female body, focusing on those bodily experiences that are unique to women, such as menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, lactation, and menopause. A second approach, inspired by French feminists Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, and Hélène Cixous, focuses on the role of discourse in constructing the female body, emphasizing that the body is a text inscribed by the structures of language and signification and hence there is no experience of the body apart from discourse. Irigaray and Cixous, exponents of écriture féminine (feminine writing), propose “writing the body,” generating new inscriptions of the female body liberated from “phallocentric” discursive practices and celebrating the alterity of woman’s sexual difference.29 The notion of sexual difference has been developed in a variety of distinctive ways by Anglo-American feminists such as Judith Butler.30 A third approach, represented by British and American Marxist feminists and other advocates of social reform, challenges the preoccupation by French feminists and other proponents of sexual difference with the discourse of woman’s body and emphasizes instead the politics of bodily praxis in which the female body is a site of political struggle involving concrete social and material realities, ranging from socioeconomic oppression and violence against women to reproductive rights and female eating disorders.31 A fourth trend of analysis, especially prevalent among American scholars, focuses on representations of the female body in the discourses of Western culture—philosophy, religion, science and medicine, literature, art, film, fashion, and so on.32

Many of the debates among theorists of the body in feminist and gender studies center on the gendered body and its relation to the sexed body, with the validity of the sex/gender distinction itself a topic of contention. On the one hand, feminist advocates of social constructionism tend to distinguish between sex and gender, in which sex (male or female) is identified with the biological body as a “natural” datum and gender (masculine or feminine) is a second-order sociocultural construction that is superimposed as an ideological superstructure on this “natural” base. On the other hand, feminist advocates of sexual difference call into question the sex/gender distinction and insist that the sexually marked biological body, like gender, is socially constructed. Butler, for example, in Bodies That Matter argues that the binary sex/gender system arises not from nature but from a system of sociocultural norms grounded in the “heterosexual imperative,” and thus sex must be construed not “as a bodily given on which the construct of gender is artificially imposed, but as a cultural norm that governs the materialization of bodies.”33

A number of scholars of religion have contributed in recent years to scholarship on the body in the social sciences and humanities. This burgeoning interest is evidenced by the increasing number of scholarly forums and publications since the 1990s dedicated to sustained reflections on the body in religion, including international conferences and seminars, special issues of religious studies journals, edited collections, review essays, and book series.34 The emerging corpus of scholarship on the body in religion is a multidisciplinary enterprise, involving the collaborative efforts of scholars of religion, philosophers, anthropologists, sociologists, historians, feminist theorists, and other scholars in the human sciences. The majority of studies have focused on body discourses and practices in particular religious traditions.35

Although a number of scholars of religion have made important contributions to our understanding of the body, the dominant trends of analysis are problematic in two ways. First, many scholars of religion have tended to simply adopt the categories of the body that have been theorized by scholars in philosophy, history, the social sciences, or feminist and gender studies: the lived body, the mindful body,36 the social body, the body politic,37 the sexual body,38 the alimentary body,39 the medical body,40 the gendered body,41 and so on. I would suggest that using such Western constructions of the body as the default cultural templates against which to compare and evaluate categories of embodiment from “the Rest of the World” serves to perpetuate the legacy of “European epistemological hegemony”42 in the academy. In order to establish “theory parity”43 in our investigations as part of the post-colonial turn, we also need to consider the potential contributions of “the Rest of the World” to theories of embodiment, and it is therefore important for scholars of religion to excavate the resources of particular religious traditions and to generate analytical categories and models of the body that are grounded in the distinctive idioms of these traditions. For example, in addition to categories such as the medical body and the gendered body, other forms of embodiment that are of particular significance to religious traditions—such as the divine body,44 the ritual body,45 and the devotional body46—need to be more fully explored from the methodological perspective of the history of religions. Second, as a result of the tendency to appropriate categories from other disciplines, we are left with a bewildering profusion of scholarly constructions of the body. Such an approach is not adequate to account for the complex integrative frameworks and taxonomies that are constructed by religious traditions to delineate the interconnections among various forms of embodiment.

A number of studies in recent years have focused on select aspects of embodiment in Hindu,47 Buddhist,48 and other South Asian religious traditions.49 Hindu traditions in particular provide extensive, elaborate, and multiform discourses of the body, and I have sought to demonstrate in my own work that a sustained investigation of these discourses can contribute in significant ways to scholarship on the body in the history of religions and in the human sciences generally.50 The body has been represented, disciplined, regulated, and cultivated from a variety of perspectives in the discursive representations and practices of Hindu traditions, including ritual traditions, ascetic movements, medical traditions, legal codes, philosophical systems, bhakti movements, yoga traditions, tantric traditions, the science of erotics, martial arts, drama, dance, music, and the visual arts.

Although Hindu discourses of the body have assumed highly diverse forms, it is nevertheless possible to isolate a number of fundamental postulates that are shared by most of these discourses and that need to be taken into consideration in our investigations.

The Body as a Psychophysical Continuum

The human body is represented as an integrated psychophysical organism that has both gross and subtle dimensions.

In contrast to Western philosophy’s emphasis on the mind/body polarity, Hindu discourses generally represent the human body as a psychophysical continuum encompassing both gross physical constituents and subtle psychic faculties.51 This notion is elaborated in two types of conceptions: the doctrine of the five sheaths (pañca-kośa) of the embodied self, and the distinction between the gross body (sthūla-śarīra) and the subtle body (sūkṣma-śarīra or liṅga-śarīra). The doctrine of the five sheaths, which is first formulated in the Taittirīya Upaniṣad,52 maintains that the embodied self (śarīra ātman) is composed of multiple layers, from the gross, outermost sheath constituted by food (anna-maya-kośa) to the increasingly subtle sheaths made of breath (prāṇa-maya-kośa), mind (mano-maya-kośa), and consciousness (vijñāna-maya-kośa) to the subtlest, innermost sheath consisting of bliss (ānanda-maya-kośa). The distinction between the gross body and the subtle body also has its roots in the Upaniṣads and is elaborated in Sāṃkhya, one of the six Darśanas, or orthodox Hindu philosophical schools, within the framework of the twenty-three tattvas (elementary principles) that constitute prakṛti, primordial matter: the gross body is constituted by the five gross elements (mahā-bhūtas), while the subtle body is made up of the intellect (buddhi or mahat), ego (ahaṃkāra), mind (manas), five sense capacities (buddhīndriyas), five action capacities (karmendriyas), and five subtle elements (tanmātras).53

An alternative formulation is proposed in one of the contending philosophical schools, Advaita Vedānta, which distinguishes three bodies: the gross body (sthūla-śarīra), which is composed of the five gross elements; the subtle body (sūkṣma-śarīra), which is made up of the intellect, mind, five sense capacities, five action capacities, and five vital breaths (prāṇas); and the causal body (kāraṇa-śarīra), which is ignorance (avidyā or ajñāna) and is the cause of the gross and subtle bodies. The Advaita school, moreover, correlates the three bodies with the five sheaths of the embodied self, identifying the sheath constituted by food with the gross body; the sheaths made of breath, mind, and consciousness with the subtle body; and the sheath consisting of bliss with the causal body.54

In these various formulations the mind, along with other psychic faculties, is represented as a subtle form of embodiment—a subtle sheath or an aspect of the subtle body—while the physical body is represented as a gross form of embodiment. The mind, like the physical body, is a type of matter, although it is a more subtle form of materiality than the physical body. The mind/body problem that has preoccupied Western philosophy is thus not a central concern in Hindu philosophical traditions. The principal problem is rather the relationship between the material psychophysical organism and the eternal Self—variously termed Ātman, Brahman, or puruṣa—which is represented as the ultimate reality that in its essential nature transcends all forms of embodiment. In Sāṃkhya and Pātañjala Yoga, as we shall see, this problem is formulated in terms of the relationship between prakṛti, primordial matter, and puruṣa, pure consciousness. In Advaita Vedānta the problem is reformulated in terms of the relationship between the phenomenal world of embodied forms—which is ultimately deemed to be māyā, an illusory appearance—and Brahman, the encompassing totality that in its essential nature is beyond all form.55

Hindu conceptions of the subtle body and subtle materiality find elaborate expression in tantric traditions, which, drawing on the ontological and psychophysiological categories of Sāṃkhya, Pātañjala Yoga, and Advaita Vedānta, re-figure the subtle body as a subtle physiology constituted by a complex network of channels (nāḍīs) and energy centers (cakras) and the serpentine power of the kuṇḍalinī.

Transmigratory History of the Body

The human body is represented as having a transmigratory history in which the subtle body reincarnates in a succession of gross bodies.

From the Upaniṣadic period on, the distinction between gross and subtle bodies assumes soteriological import as an integral part of the doctrine of karma and rebirth. The subtle body is represented in this context as the transmigratory body that reincarnates in a series of gross bodies. The character and destiny of an embodied self in any given lifetime is determined by the combined influence of the two bodies: the karmic heritage from the subtle body, which is the repository of the karmic residues accumulated from previous births, and the genetic heritage from the gross body, which is the repository of the genetic contributions of the current father and mother. In the Upaniṣads and later ascetic traditions, as well as in philosophical schools such as Sāṃkhya, Pātañjala Yoga, and Advaita Vedānta, all forms of embodiment—gross and subtle—are represented as a source of bondage because they bind the soul to saṃsāra, the endless cycle of birth and death. Mokṣa, liberation from saṃsāra, is construed in this context as freedom from the fetters of embodiment and realization of the essential nature of the eternal Self beyond the material psychophysical complex.

The Person, the Self, and the Body

Constructions of embodiment in different Hindu traditions are embedded in distinctive ontologies and notions of the person and the self.

Many Hindu traditions distinguish between the empirical self in bondage, which mistakenly identifies with the psychophysical complex in the material realm of prakṛti, and the eternal Self, which is beyond the realm of prakṛti. In such traditions embodiment is generally represented as a fundamental problem of the human condition that is inextricably implicated in the bondage of materiality.

Constructions of embodiment in classical Sāṃkhya, as expounded in the Sāṃkhya-Kārikā of Īśvarakṛṣṇa (c. 350–450 CE), are based on a dualistic ontology that posits a plurality of puruṣas that are eternally distinct from prakṛti, primordial matter. Puruṣa is pure consciousness, which is the eternal, nonchanging Self that is the silent, uninvolved witness of the ever-changing transformations of prakṛti. Bondage is caused by ignorance (avidyā) of puruṣa as distinct from prakṛti. The jīva, empirical self, mistakenly identifies with the activities of the ego, intellect, and mind, which are subtle forms of materiality, and is thereby subject to the binding influence of prakṛti and its continuum of pleasure and pain that is perpetuated through the cycle of birth and death. Liberation from bondage is attained through the discriminative knowledge (jñāna) that distinguishes between puruṣa and prakṛti. The enlightened sage, having realized the luminous reality of puruṣa, the nonchanging Self, attains kaivalya, a state of absolute isolation and freedom in which identification with the dance of prakṛti, the ever-changing realm of embodiment, ceases.

The classical Yoga system, which is first articulated in the Yoga-Sūtras of Patañjali (c. 400–500 CE), builds upon the ontology and epistemology of Sāṃkhya in its discussions of the nature of embodiment, bondage, and liberation. However, in contrast to Sāṃkhya’s emphasis on discriminative knowledge, Pātañjala Yoga gives primary emphasis to practical methods of purification and meditation as means to liberation. It outlines an eight-limbed program termed aṣṭāṅga-yoga, which comprises physical and mental disciplines aimed at purifying the material psychophysical complex (śarīra) and attenuating the afflictions (kleśas) and the residual karmic impressions (saṃskāras) that perpetuate the cycle of rebirth. The first four limbs involve external practices, including a series of vows of abstinence (yama), psychophysical disciplines (niyama), bodily postures (āsana), and breathing exercises (prāṇāyāma). The fifth limb involves withdrawal of the mind from external sense objects (pratyāhāra) in preparation for the internal practice of saṃyama, a threefold meditation technique that encompasses the final three limbs, comprising two phases of meditation (dhāraṇā and dhyāna) and culminating in samādhi, an enstatic experience of absorption in the Self, puruṣa, which is pure consciousness. Through sustained practice of aṣṭāṅga-yoga the yogin ceases to identify with the fluctuations of ordinary empirical awareness (citta-vṛtti) and attains direct experiential knowledge (viveka-khyāti) of the true nature of puruṣa as separate from the realm of prakṛti and from other puruṣas. The liberated yogin, having become permanently established in the nonchanging Self, puruṣa, enjoys eternal freedom in kaivalya, a state of absolute isolation, and attains a perfected body (kāya-sampad) that manifests siddhis, psychophysical powers, as an externalized expression of the yogin’s enlightened consciousness.56

In classical Advaita Vedānta, as expounded by Śaṃkara (c. 788–820 CE), constructions of embodiment are based on a monistic ontology in which the duality of puruṣa and prakṛti is subsumed within the totality of Brahman, the universal wholeness of existence, which alone is declared to be real. Brahman is described as an impersonal totality consisting of being (sat), consciousness (cit), and bliss (ānanda), which in its essential nature is nirguṇa (without attributes) and completely formless, distinctionless, nonactive, nonchanging, and unbounded. As saguṇa (with attributes), Brahman assumes the form of Īśvara, the personal God who manifests the phenomenal world of forms as māyā, an illusory appearance. Deluded by ignorance (avidyā), the jīva, empirical self, becomes enchanted by the cosmic play and mistakenly identifies with the material psychophysical complex (śarīra), becoming bound in saṃsāra. The goal of human existence is mokṣa or mukti, liberation from the bondage of saṃsāra and the fetters of embodiment, which is attained through knowledge (jñāna or vidyā) alone. When knowledge dawns the jīva awakens to its true nature as Ātman, the eternal, universal Self, and realizes its identity with Brahman. In this embodied state of liberation, jīvanmukti, the liberated sage enjoys a unitary vision of the all-pervasive effulgence of Brahman in which he sees the Self in all beings and all beings in the Self.57

The discourse of embodiment developed by the sixteenth-century exponents of the Gauḍīya Sampradāya, which will be a major focus of the present study, rejects both the dualistic ontology of Sāṃkhya and Pātañjala Yoga and the monistic ontology of Advaita Vedānta. The Gauḍīyas promulgate instead the ideal of acintya-bhedābheda, inconceivable difference-in-nondifference, which re-visions prevailing notions of the relationship between embodiment, personhood, and materiality on both the divine and human planes. On the one hand, they assert the deity Kṛṣṇa’s supreme status as pūrṇa Bhagavān, the full and complete Godhead, who is beyond the impersonal, formless Brahman and is supremely personal and possessed of an absolute body (vigraha) that is nonmaterial. On the other hand, they maintain that the goal of human existence is for the jīva, individual living being, to awaken to its svarūpa, its unique inherent nature, as a part (aṃśa) of Bhagavān and to realize the particular form of its siddha-rūpa, its eternal, nonmaterial body made of bliss. The highest state of realization is thus represented as an eternal relationship between two persons—Kṛṣṇa, the supreme Bhagavān, and the individual jīva—each of whom possesses a body that is eternal and nonmaterial. In the Gauḍīya perspective, as we shall see, the body is not a problem to be overcome but, on the contrary, is ascribed a pivotal role on multiple levels—divine and human, material and nonmaterial—as the very key to realization.58

Constructions of embodiment are not limited to the human body but rather include a hierarchy of structurally correlated bodies corresponding to different planes of existence: the human body, the social body, the cosmos body, and the divine body.

Vedic taxonomies posit a system of inherent connections (bandhus) among the different orders of reality: the divine order (adhidaiva), the natural order (adhibhūta), and the human order (adhyātma), which includes the psychophysical organism as well as the social order. These orders of reality are at times represented as a hierarchy of structurally correlated bodies, nested one within the other: the human body, the social body, the cosmos body, and the divine body. I term these bodies “integral bodies” in that each is represented as a complex whole that is inherent in the structure of reality. The earliest formulation of this fourfold hierarchy of bodies is found in the famous Puruṣa-Sūkta, Ṛg-Veda 10.90, which is the locus classicus that is frequently invoked in later Vedic and post-Vedic discourses of the body. In this formulation the divine body is the encompassing primordial totality, which transcends and at the same time replicates itself in the structures of the cosmos body, the social body, and the human body; the cosmos body is the body of the universe, which is the differentiated manifestation of the divine body; the social body is the system of social classes (varṇas), which is inherent in the structure of the divine body; and the human body is the microcosmic manifestation of the divine body, which is ranked according to class and gender in the social body. A system of homologies is thus established between the transcosmic divine body, the macrocosmic cosmos body, the microcosmic human body, and the social body, which is the intermediate structure between the microcosm and the macrocosm.

This fourfold model persists in later Vedic and post-Vedic discourses of the body, although the relative importance of, and interrelationship among, the four integral bodies is reconfigured to accord with the epistemological perspective of each discourse. This fourfold model is further complicated by post-Vedic taxonomies that, building on earlier Vedic taxonomies, distinguish among different classes of deities (devas) and also delineate a manifold array of subtle beings (bhūtas) who inhabit subtle worlds between the divine and human realms and who each have their own distinctive forms of embodiment. These subtle beings include gandharvas (celestial musicians), apsarases (celestial dancing nymphs), nāgas (semidivine serpents), and yakṣas (chthonic spirits); various classes of demonic beings such as asuras, rākṣasas, and piśācas; and disembodied human spirits such as pretas (ghosts) and pitṛs (ancestors).

The human body is represented as assuming various modalities in order to mediate transactions among the social body, the cosmos body, and the divine body.

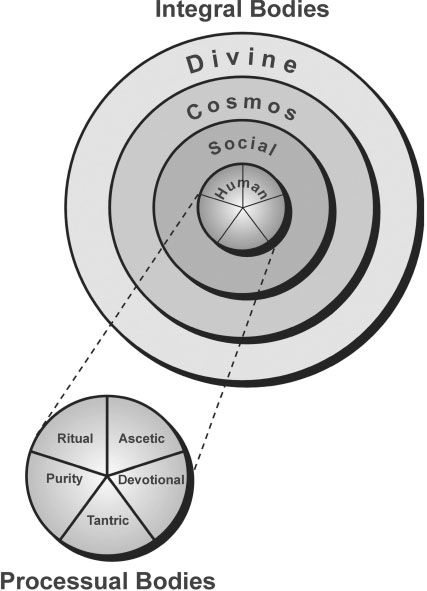

In Hindu traditions the human body is generally represented not as “individual” but as “dividual”—to use McKim Marriott’s term—that is, a constellation of substances and processes that is connected to other bodies through a complex network of transactions.59 The dividual human body is represented in different traditions as assuming distinctive modalities—which I term “processual bodies”—in order to mediate transactions among the social body, the cosmos body, and the divine body. Among the various types of processual bodies that have assumed central importance in Vedic and post-Vedic traditions, my own work has focused on the ritual body, the ascetic body, the purity body, the tantric body, and the devotional body.60 Each of these processual bodies is constituted by specific practices and adopts a distinctive configuration of transactions with the various integral bodies (see Figure 1).61

Figure 1 Integral Bodies and Processual Bodies.

Ritual Body. Vedic sacrificial traditions, as represented in the Vedic Saṃhitās (c. 1500–800 BCE) and the Brāhmaṇas (c. 900–650 BCE), ascribe central importance to the ritual body as the modality of embodiment that mediates the inherent connections (bandhus) among the divine body, the cosmos body, the social body, and the human body. As mentioned earlier, the earliest formulation of this quadripartite model is found in the Ṛg-Veda Saṃhitā (c. 1500–1200 BCE) in the Puruṣa-Sūkta, Ṛg-Veda 10.90. The Puruṣa-Sūkta depicts the primordial yajña, sacrifice, by means of which the wholeness of the body of Puruṣa, the cosmic Man, is differentiated, the different parts of the divine anthropos giving rise to the different parts of the universe. The divine body of Puruṣa is represented as the paradigmatic ritual body, the body of the sacrifice itself, which serves as the means of manifesting the cosmos body, the social body, and the human body. This model is extended and adapted in the Brāhmaṇas (c. 900–650 BCE), sacrificial manuals attached to the Saṃhitās, which foster a discourse of sacrifice that centers on the divine body of the Puruṣa Prajāpati, the primordial sacrificer, and on the theurgic efficacy of the yajña, sacrificial ritual, as the instrument that constitutes the divine body and its corporeal counterparts and then enlivens the connections among this fourfold hierarchy of integral bodies.62 First, the yajña is celebrated as the cosmogonic instrument through which the creator Prajāpati generates the cosmos body, setting in motion the entire universe, bringing forth all beings, and structuring an ordered cosmos. Second, the yajña is represented as the theogonic instrument through which the divine body of Prajāpati himself, which is disintegrated and dissipated by his creative efforts, is reconstituted and restored to a state of wholeness. Third, the yajña is portrayed as the anthropogonic instrument that ritually reconstitutes the embodied self of the yajamāna—the patron of the sacrifice, who is the human counterpart of Prajāpati—in the form of a divine self (daiva ātman) through which he can ascend to the world of heaven (svarga loka). Finally, the yajña is represented as the sociogonic instrument that constructs and maintains the social body as a hierarchy of bodies differentiated according to social class (varṇa) and gender.

Ascetic Body. In the metaphysical speculations of the classical Upaniṣads (c. 800 BCE–200 CE), the epistemological framework shifts from the discourse of yajña, sacrifice, to the discourse of jñāna, knowledge. In accordance with the ascetic interests of the forest-dwelling Upaniṣadic sages, the Upaniṣads’ discursive reshaping of the body interjects two new emphases. First, the divine body is recast in relation to the ultimate reality—generally designated as Brahman or Ātman—which is the focus of the Upaniṣads’ ontological and epistemological concerns. Second, the ascetic body displaces the ritual body as the most important modality of human embodiment, which is to be cultivated through minimizing transactions with the cosmos body and the social body in order to attain realization of Brahman-Ātman. The Upaniṣadic sages locate the source of bondage in the embodied self’s attachment to the material psychophysical complex and consequent failure to recognize its true identity as Brahman-Ātman, which in its essential nature is unmanifest, nonchanging, unbounded, and beyond all forms of embodiment. In this context the human body is often ascribed negative valences, becoming associated with ignorance, attachment, desire, impurity, vices, disease, suffering, and death. In contrast to the ritual body—which is constituted as a means of enlivening the connections among the divine body, the cosmos body, the social body, and the human body—the ascetic body, as described in the Upaniṣads and in later post-Vedic ascetic traditions, is constituted as a means of overcoming attachment to all forms of embodiment. The regimen of practices that structures the ascetic body includes disciplines of celibacy aimed at restraining the sexual impulse; practices of begging and fasting aimed at minimizing food production and consumption; and meditation techniques, breathing exercises, and physical austerities aimed at disciplining and transforming the mind, senses, and bodily appetites.

Purity Body. In the Dharma-Śāstras (c. first to eighth centuries CE), brahmanical legal codes, the body is re-figured in accordance with the epistemological perspective of the discourse of dharma, and more specifically varṇāśrama-dharma, the system of ritual and social duties that regulates the four social classes (varṇas) and the four stages of life (āśramas).63 The Dharma-Śāstras’ discursive reshaping of the inherited models of embodiment results in two new emphases. First, the ideological representations of the Dharma-Śāstras give priority to the social body among the four integral bodies. They attempt to provide transcendent legitimation for the brahmanical system of social stratification by invoking the imagery of the Puruṣa-Sūkta in which the body of the divine anthropos is portrayed as the ultimate source of the hierarchically differentiated social body consisting of four varṇas. Second, the modality of human embodiment that is of central significance to the Dharma-Śāstras is the purity body, which must be continually reconstituted through highly selective transactions with the cosmos body and the social body in order to maintain the smooth functioning of the social and cosmic orders. In the discourse of dharma the purity body is not a given but rather an ideal to be approximated, for the human body is considered the locus of polluting substances associated with bodily processes and secretions, such as urine, feces, semen, menses, saliva, phlegm, and sweat. The purity body, its boundaries constantly threatened by the inflow and outflow of impurities, must be continually reconstituted. The regulations and practices delineated in the Dharma-Śāstras for structuring the purity body focus in particular on the laws that govern the system of interactions among castes (jātis), including the laws of connubiality that regulate marriage transactions among castes and the laws of commensality that circumscribe food transactions among castes, determining who may receive food and water from whom.

Tantric Body. In tantric traditions the body is reimagined in accordance with the epistemological framework of the discourse of tantra. The nondual Trika Śaiva tradition of Kashmir (c. ninth to eleventh centuries CE), for example, delineates a multileveled tantric ontology in which the absolute body of Paramaśiva, the ultimate reality, manifests itself simultaneously on the macrocosmic level as the cosmos body and on the microcosmic level as the human psychophysiology. This discursive reframing of the body results in two new emphases. First, among the four integral bodies, the human body is given precedence as the principal locus of embodiment onto which the divine body and the cosmos body are mapped in the form of the subtle physiology, which consists of an elaborate network of nāḍīs (channels) and cakras (energy centers) and the kuṇḍalinī. Second, the ideal modality of human embodiment is envisioned as a tantric body, in which the material body (bhautika-śarīra) is transformed into a divinized body (divya-deha). The tantric body is constituted through an elaborate system of ritual and meditative practices, termed sādhana, that involves instantiating the divine-cosmos body in the human psychophysiology with the aid of such devices as bīja-mantras (seed-syllables), maṇḍalas and yantras (geometric diagrams), mūrtis (ritual images), and mudrās (bodily gestures).

Devotional Body. In bhakti traditions the body is re-figured to accord with the epistemological perspective of the discourse of bhakti, devotion, which interjects two new emphases. First, among the fourfold hierarchy of integral bodies, the divine body is given precedence and is represented in a standardized repertoire of particularized forms of the deity who is revered as the object of devotion—whether Viṣṇu, Kṛṣṇa, Śiva, or Devī (the Goddess). Second, the modality of human embodiment that is of central significance is the devotional body, which is to be cultivated as a means of encountering, engaging, and experiencing the deity. The Gauḍīya tradition provides a robust example of the multileveled models of embodiment that are integral to many bhakti traditions. The discourse of embodiment developed by the early Gauḍīya authorities in the sixteenth century CE celebrates the deity Kṛṣṇa as ananta-rūpa, “he who has endless forms,” his limitless forms encompassing and interweaving all aspects of existence: as Bhagavān, the supreme personal Godhead, who is endowed with an absolute body (vigraha) that is nonmaterial; as Paramātman, the indwelling Self, who on the macrocosmic level animates the innumerable universes, or cosmos bodies, and on the microcosmic level dwells in the hearts of all embodied beings; as Brahman, the impersonal, formless ground of existence, which is the radiant effulgence of the absolute body of Bhagavān; and as the avatārin, the source of all avatāras (divine descents), who descends to the material realm periodically and assumes a series of forms in different cosmic cycles. The Gauḍīyas delineate an elaborate regimen of practices, termed sādhana-bhakti, by means of which the bhakta can realize a siddha-rūpa, a perfected devotional body that is eternal and nonmaterial, and rise to that sublime state of realization in which he or she savors the exhilarating sweetness of Kṛṣṇa-preman—the fully mature state of all-consuming love for Kṛṣṇa—in eternal relationship with Bhagavān.

In a separate study I have provided an extended analysis of the discursive representations and practices associated with these five processual bodies—ritual body, ascetic body, purity body, tantric body, and devotional body—in distinct Hindu discourses of the body, along with an exploration of the connections between these modes of embodiment and notions of the person and the self.64 My focus in the present study is on the role of embodiment in bhakti traditions and more specifically on the mechanisms through which devotional bodies are constituted in dynamic engagement with divine bodies in Kṛṣṇa bhakti traditions.

The term bhakti, from the root bhaj, “to share, partake of,” is first and foremost about relationship. Among the earliest occurrences of the term, in Pāṇini’s Aṣṭādhyāyī (c. 500–400 BCE)65 and the Mahābhārata (c. 200 BCE–100 CE) the term bhakti is at times used to refer to a relationship of loyalty, service, and homage to a king or military leader, while in the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad (c. 400–200 BCE)66 and the Bhagavad-Gītā (c. 200 BCE) the meaning of the term is extended to include service, reverence, love for, and devotion to a deity. In later bhakti traditions the term is also at times extended further to include the guru as the object of bhakti.

Bhakti, as a term concerning a relationship with a deity, connotes sharing in, partaking of, and participating in the deity as Other. The various traditions that constitute themselves in relation to the category bhakti tend to posit an initial duality between the bhakta as subject and the divine Other as object and then delineate a path by means of which the bhakta can overcome the state of separation and engage in an increasingly intimate relationship with the divine Other conceived of as a personal God. This relationship finds fruition in the ultimate goal of union with the deity, which is variously represented, ranging from a state of union-in-difference to a state of undifferentiated unity without duality. Bhakti, as a term connoting partaking of and participation in the deity, is thus at times invoked as both a means and an end, as constitutive of the path as well as of the goal.67

In order to illuminate the connections between bhakti and embodiment and to highlight more specifically the various factors that tend to distinguish highly embodied traditions and less embodied traditions, I would like to briefly examine the role of embodiment in the emergence of bhakti traditions.

The period between 200 BCE and 200 CE marks the transition from the Vedic period to the post-Vedic period in which a new brahmanical synthesis—that “federation of cultures popularly known as Hinduism”68—emerged, which attempted to bring together and reconcile diverse strands of Indian thought and practice. Although certain proto-bhakti currents may be found in Vedic traditions, it is only in the period between 200 BCE and 200 CE that we see the emergence of popular bhakti movements. The bhakti stream, the underground currents of which may have been gathering force for centuries, suddenly bursts forth in certain areas of the Indian subcontinent in the last centuries before the Common Era, finding expression in the rise of sectarian devotional movements centering on the deities Viṣṇu and Śiva and in the upsurge of multiform vernacular traditions venerating a panoply of goddesses at the local village level.

The historical shift from Vedic traditions to post-Vedic bhakti traditions is accompanied by a shift from abstract, translocal notions of divinity to particularized, localized notions of divinity and a corresponding shift from aniconic to iconic traditions and from temporary sacrificial arenas to established temple sites. A. K. Ramanujan has provided a succinct encapsulation of a number of features that define this historical shift:

This shift [from Vedic to bhakti traditions] is paralleled by other religious shifts: from the noniconic to the iconic; from the nonlocal to the local; from the sacrificial-fire rituals (yajña and homa) meant to be performed only by Vedic experts to worship (pūjā) by nearly all; from rituals in which a plot of ground is temporarily cordoned off and made into sacred space by experts in a consecration rite—to worship in temples, localized, named, open to almost the whole range of Hindu society. These changes are accompanied by a shift away from the absolute godhead, the non-personal Brahman of the Upaniṣads, to the gods of the mythologies, with faces, complexions, families, feelings, personalities, characters. Bhakti poems celebrate god as both local and translocal, and especially as the nexus of the two.69

I would argue that the various transformations that characterize this historical shift from Vedic traditions to post-Vedic bhakti traditions are a direct consequence of newly emerging discourses of the body in bhakti traditions in which constructions of divine embodiment proliferate, celebrating the notion that a deity, while remaining translocal in his or her essential nature, can appear in manifold corporeal forms and assume various types of concentrated presence in different times and different localities on different planes of existence.70 These new constructions of divine embodiment can be distinguished from earlier Vedic formulations in seven ways.

Particularized Divine Bodies. In contrast to Vedic texts, which make formulaic allusions to the bodies of gods and goddesses while eschewing individualized descriptions of their corporeal forms, bhakti traditions develop elaborate and particularized descriptions of the bodies of the deities.71 The rise of bhakti traditions is accompanied by the elaboration of iconographic and mythological traditions in which each of the major deities becomes associated with a standardized repertoire of particularized forms, with distinctive postures, gestures, and emblems.

Embodiment of the Divine in Time. The emergence of bhakti traditions is accompanied by the development of post-Vedic notions of “divine descent”—designated by the terms avatāra, avataraṇa, or other substantive forms derived from the root tṝ + ava, “to descend”—in which certain deities are represented as descending from their divine abodes to the material realm periodically and becoming embodied in manifest forms—whether divine, human, animal, or hybrid forms—in different cosmic cycles.72

Embodiment of the Divine in Place. In Vedic yajñas a sacrificial arena is temporarily cordoned off and particular deities are invoked to become present at the seat of sacrifice and to receive the oblations offered into the sacrificial fire, after which the deities are invited to depart and the sacrificial arena is destroyed. In contrast to the temporary constructions of sacred space and translocal notions of divinity associated with Vedic traditions, bhakti traditions foster locative discourses and practices centering on sacred sites, or tīrthas (from the root tṝ, “to cross over”), that function as “crossing-places” in which deities become embodied in particular locales. As the counterpart of the notion of avatāra, the concept of tīrtha encompasses the multiple places on earth to which deities descend from their divine abodes, assuming localized forms in particular geographic features such as rivers, mountains, forests, rock outcroppings, and caves, or infusing their divine presence in the landscape of an entire region. Tīrthas, as centers of concentrated divine presence associated with particular deities, are variously represented as manifestations of the deity, parts of the deity’s body, special abodes (dhāmans) of the deity, or sites of the deity’s divine play (līlā). Bhakti communities develop a variety of means to visibly mark such places as sacred—in particular, through building architectural structures such as temples and shrines to mark the sites of divine presence and then investing these built structures with the status of tīrthas. In addition, tīrtha-yātrā, pilgrimage to tīrthas, is ascribed primacy of place in the emerging complex of bhakti practices as a ritual alternative to Vedic yajñas that is in principle open to people at all levels of the socioreligious hierarchy.73

Embodiment of the Divine in Image. In contrast to the aniconic orientation of the Vedic tradition,74 in bhakti traditions the notion of avatāra, divine descent in time, and the notion of tīrtha, divine instantiation in place, converge in conceptions of image-incarnations in which ritual images (mūrtis or arcās) are revered as localized embodiments of the deity.75

Embodiment of the Divine in Name. Vedic conceptions of language, in which the names (nāmans) contained in the Vedic mantras are held to be the sound correlates that contain the subtle essence and structure of the forms (rūpas) that they signify, are extended and recast in bhakti formulations concerning divine names (nāmans) in which the name is extolled as the sonic form of the deity.76

Embodiment of the Divine in Text. Vedic constructions of scripture, in which the body of the creator Prajāpati or the body of Brahman-Ātman is held to be constituted by the Vedic mantras, are appropriated and reinterpreted in bhakti traditions with reference to their own sacred texts.77 In certain bhakti reformulations the deity is celebrated as becoming embodied in a variety of different kinds of sacred texts, ranging from Sanskritic smṛti texts that emulate the paradigmatic Veda to vernacular hymns that are revered as text-embodiments of the deity. Moreover, the notion of divine embodiment is extended beyond oral texts to include written texts as well, in which the concrete book is viewed as an incarnate form of the deity that is to be worshiped accordingly.

Embodiment of the Divine in Human Form. Bhakti traditions foster a variety of notions in which the deity assumes corporeal form in a human body. In such conceptions certain human beings—in particular, realized gurus, poet-saints, and exalted bhaktas—are revered as localized embodiments of the deity. The deity is also held to descend and become temporarily instantiated in particular human bodies through a variety of embodied practices, including ritual possession, dance, and dramatic performances.

This constellation of notions pertaining to divine bodies—along with the associated practices through which devotional bodies are constituted in relation to these modes of divine embodiment—is configured in a variety of ways in early bhakti traditions. A number of these notions and practices are found in incipient form in the Mahābhārata (c. 200 BCE–100 CE)—the first Sanskritic work to allot a significant place to bhakti—and are further crystallized and expanded in the Harivaṃśa (c. 200 CE), the appendix to the Mahābhārata, and in the early Purāṇas that derive from the Gupta Period (c. 320–550 CE). Certain epic and Purāṇic traditions pertaining to these various modes of divine embodiment are in turn selectively appropriated and reimagined in the earliest full-fledged bhakti movements for which we have textual witness in the form of devotional poetry: the Tamil Vaiṣṇava poet-saints known as the Āḻvārs and their Tamil Śaiva counterparts, the Nāyaṉārs and Māṇikkavācakar, who flourished in the Tamil-speaking areas of South India between the sixth and ninth centuries CE.

An exploration of the connections between bhakti and embodiment can thus serve to illuminate a number of the transformations that characterize the historical shift from Vedic traditions to post-Vedic bhakti traditions. Moreover, I would suggest that such an investigation is critical to our understanding of the myriad forms that bhakti has historically assumed up to the present time, for embodiment is integral to the oral-aural and performative dimensions of devotional practices through which bhaktas engage the deity in his or her various embodied forms: tīrtha-yātrā, pilgrimage to the sacred places in which the deity’s presence is held to be instantiated; pūjā, ritual offerings to the image-incarnations of the deity in temples and shrines; nāma-kīrtana, singing the divine names as a means of engaging the sonic forms of the deity; paṭhana, recitation of the scriptures and devotional hymns that are revered as text-embodiments of the deity; līlā-kīrtana, singing and recounting the stories of the divine play of the deity in various bodily forms; and rāsa-līlā and nṛtya, dramatic and dance performances in which the performers are revered as living forms (svarūpas), or temporary instantiations, of the deity. All of these practices are embodied practices—practices through which the bodies of bhaktas engage the embodied forms of the deity. Karen Pechilis Prentiss, in her study of Tamil Śaiva bhakti from the seventh to fourteenth centuries CE, has argued that bhakti functions as a “theology of embodiment” for Tamil Śaivas and for bhakti traditions generally.78 More recently, Christian Novetzke, building on Pechilis Prentiss’s insights, has emphasized that embodiment has not only assumed a critical role in the sociocultural construction of particular bhakti communities but, more broadly, constitutes the “very epicenter” of what he terms the “publics of bhakti.”

Just as the public sphere requires literacy, the publics of bhakti in South Asia require “embodiment,” the human as medium. This very useful notion of “embodiment” does not simply exist as a trope of literature, but is deeply engaged in the performance of the discourse of bhakti. By “discourse” I mean the manifestation of bhakti not only in performance through song or literacy, but also through all those actions and bodily displays that make up bhakti in the broadest sense, such as … pilgrimage, pūjā, darśan, the wearing of signs on the body, and so on. Embodiment, then, is not so much a technique of bhakti as its very epicenter: bhakti needs bodies.79

I would suggest that an investigation of embodiment as the “very epicenter” of bhakti can illuminate correlations among the array of ontologies, devotional modes, goals, and practices found in bhakti traditions. In this context I would posit, as a heuristic device, a spectrum of bhakti traditions characterized by varying degrees of embodiment, with highly embodied traditions at one end of the spectrum and less embodied traditions at the other end. Highly embodied bhakti traditions tend to be correlated with ontologies that celebrate the manifold forms of the Godhead, modes of bhakti that favor more passionate and ecstatic expressions of devotion, and formulations of the goal of life that emphasize the state of union-in-difference in which the bhakta savors the embrace of the deity in eternal relationship. Exemplars of highly embodied traditions include the Āḻvārs Nammāḻvār and Āṇṭāḷ (c. ninth century CE), the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (c. ninth to tenth century CE), and Caitanya (1486–1533 CE) and his Gauḍīya followers. Less embodied bhakti traditions tend to be correlated with ontologies that emphasize the formlessness of the Godhead in its essential nature, modes of bhakti that favor more contemplative forms of devotion, and formulations of the goal of life that emphasize the state of undifferentiated unity without duality in which the bhakta merges with the deity. Among the exemplars of less embodied traditions, I would single out Kabīr (c. 1398–1448 CE) in particular.80

In the following chapters I will interrogate a number of categories and practices that are critical to our understanding of the role of embodiment in bhakti traditions, focusing in particular on the highly embodied discourses of Kṛṣṇa bhakti expressed in seminal form in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and richly elaborated in the Gauḍīya tradition, which can serve as case studies to illustrate how issues of embodiment are grappled with in specific discursive frameworks.

The Bhāgavata Purāṇa, the consummate textual monument to Vaiṣṇava bhakti, is generally held to have originated between the ninth and tenth centuries CE81 in South India.82 The Bhāgavata establishes itself as an authoritative, encompassing scripture by integrating the religiocultural traditions of South India and North India and reconciling the claims of Vaiṣṇava bhakti with brahmanical orthodoxy. More specifically, it adopts the canonical form of a Purāṇa and incorporates the South Indian devotional traditions of the Āḻvārs within a brahmanical Sanskritic framework that reflects North Indian ideologies.83

Friedhelm Hardy, in his landmark study of the early history of Kṛṣṇa devotion in South India, has argued persuasively that the Bhāgavata Purāṇa is “an attempt to render in Sanskrit (and that means inter alia to make available for the whole of India) the religion of the Āḻvārs.”84 Regarding the Bhāgavata’s role in Sanskritizing the Tamil bhakti of the Āḻvārs and contributing to the synthesis of North Indian and South Indian traditions, he remarks: