CHAPTER 8

Exercising for Endurance: Aerobic Activities

WHEN THINKING ABOUT AEROBIC (ENDURANCE) EXERCISE, many people are confused about what to do and how much to do. We describe the guidelines for aerobic, flexibility, and strengthening exercise in Chapter 6. Figuring out your very own program may be a challenge. The guidelines recommend that adults exercise at a moderate intensity for at least 150 minutes spread out through the week. There are many ways to work aerobic activities into your day. In this chapter you will learn about exercise effort, various aerobic activities, and how to put together a program that works for you. The most important thing is that some activity is better than none. If you start off doing what is comfortable and increase your efforts gradually, it is likely that you will build a healthy, lifelong habit. You will learn how to stay active and how to get back to activity even when changes in your condition may slow you down for a while. Generally, it is better to begin your program by underdoing rather than overdoing.

You can adjust your exercise effort and work toward your goal by using the three basic building blocks: frequency, time, and intensity.

Frequency is how often you exercise. Most guidelines suggest doing at least some exercise most days of the week. Three to five times a week is a good choice for moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Taking every other day off gives your body a chance to rest and recover.

Frequency is how often you exercise. Most guidelines suggest doing at least some exercise most days of the week. Three to five times a week is a good choice for moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Taking every other day off gives your body a chance to rest and recover.

Time is the length of each exercise period. According to the guidelines, it is best if you can exercise at least 10 minutes at a time. You can add up 10-minute exercise periods all week to work toward 150 minutes. For example, three 10-minute walks a day for 5 days gets you to 150 minutes for the week. If 10 minutes is too much at first, start with what you can do and work toward 10 minutes.

Time is the length of each exercise period. According to the guidelines, it is best if you can exercise at least 10 minutes at a time. You can add up 10-minute exercise periods all week to work toward 150 minutes. For example, three 10-minute walks a day for 5 days gets you to 150 minutes for the week. If 10 minutes is too much at first, start with what you can do and work toward 10 minutes.

Intensity is your exercise effort—how hard you are working. Aerobic exercise is safe and effective at a moderate intensity. When you exercise at moderate intensity, you’ll feel warmer, you’ll breathe more deeply and faster than usual, and your heart will beat faster than normal. At the same time, you will feel that you can continue for a while longer. Exercise intensity is relative to your fitness. For an athlete, running a mile in 10 minutes is probably low-intensity exercise. For a person who hasn’t exercised in a long time, a brisk 10-minute walk may be moderate to high intensity. For someone with severe physical limitations, a slow walk may be high intensity. The trick, of course, is to figure out what is moderate intensity for you. There are several easy ways to do this.

Intensity is your exercise effort—how hard you are working. Aerobic exercise is safe and effective at a moderate intensity. When you exercise at moderate intensity, you’ll feel warmer, you’ll breathe more deeply and faster than usual, and your heart will beat faster than normal. At the same time, you will feel that you can continue for a while longer. Exercise intensity is relative to your fitness. For an athlete, running a mile in 10 minutes is probably low-intensity exercise. For a person who hasn’t exercised in a long time, a brisk 10-minute walk may be moderate to high intensity. For someone with severe physical limitations, a slow walk may be high intensity. The trick, of course, is to figure out what is moderate intensity for you. There are several easy ways to do this.

Talk Test

When exercising, talk to another person or yourself, or recite poems out loud. Moderate-intensity exercise allows you to speak comfortably. If you can’t carry on a conversation because you are breathing too hard or are short of breath, you’re working at a high intensity. Slow down to a more moderate level. The talk test is an easy and quick way to recognize your effort and regulate intensity. If you have lung disease, the talk test might not work for you. If that is the case, try using the perceived-exertion scale.

Perceived Exertion

Another way to monitor intensity is to rate how hard you’re working on a scale of perceived exertion. There are two scales: 0 to 10 and 6 to 20. On the 0-to-10 scale, 0, at the low end of the scale, is lying down, doing no work at all, and 10 is equivalent to working as hard as possible, very hard work that you couldn’t do for more than a few seconds. A good level for moderate aerobic exercise on the 0-to-10 scale is between 4 and 5.

On the 6-to-20 scale, 6 is considered the same as sitting quietly and 20 as working as hard as possible. On the 6-to-20 scale, moderate intensity is between 11 and 14.

Use whichever scale that you like better.

Heart Rate

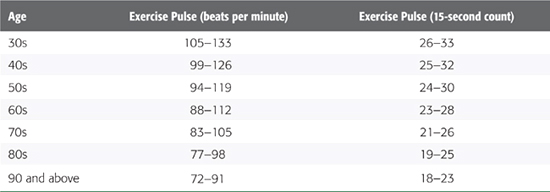

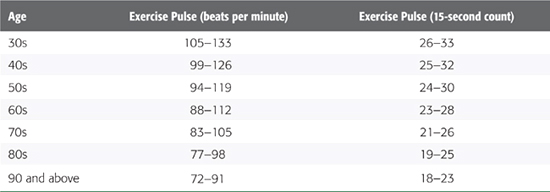

Unless you’re taking heart-regulating medicine (such as the beta-blocker propranolol), checking your heart rate is another way to measure exercise intensity. The faster the heart beats, the harder you’re working. (Your heart also beats fast when you are frightened or nervous, but here we’re talking about how your heart responds to physical activity.) Endurance exercise at moderate intensity raises your heart rate to a range between 55% and 70% of your safe maximum heart rate. The safe maximum heart rate declines with age, so your safe exercise heart rate gets lower as you get older. You can follow the general guidelines of Table 8.1 or calculate your own exercise heart rate using the formula we’re about to give you. Either way, you need to know how to take your pulse.

Take your pulse by placing the tips of your index and middle fingers at your wrist below the base of your thumb. Move your fingers around, but don’t push down, until you feel the pulsations of blood pumping with each heartbeat. Count how many beats you feel in 15 seconds. Multiply this number by 4. Start by taking your pulse whenever you think of it, and you’ll soon learn the difference between your resting and exercise heart rates. Most people have a resting heart rate between 60 and 100 beats per minute.

Here’s how to calculate your own exercise heart rate range:

1. Subtract your age from 220:

Example: 220 − 60 = 160

You: 220 − ______ = ______

2. To find the low end of your exercise heart rate range, multiply your answer in step 1 by 0.55:

Example: 160 × 0.55 = 88

You: ______ × 0.55 = ______

3. To find the upper end of your moderate intensity range, multiply your answer in step 1 by 0.7:

Example: 160 × 0.7 = 112

You: ______ × 0.7 = ______

The exercise heart rate range for moderate intensity in our example is from 88 to 112 beats per minute. What is yours?

You only need to count your pulse for 15 seconds, not a whole minute. To find your 15-second pulse for exercise, divide both the lower-end and upper-end numbers by 4. The person in our example should be able to count between 22 (88 ÷ 4) and 28 (112 ÷ 4) beats in 15 seconds while exercising.

Table 8.1 Moderate-Intensity Exercise Heart Rate, by Age

The most important reason for knowing your exercise heart rate range is so that you can learn not to exercise too vigorously. After you’ve done your warm-up and 5 minutes of endurance exercise, take your pulse. If it’s higher than the upper rate, don’t panic. Just slow down a bit. You don’t need to work so hard.

If you are taking medicine that regulates your heart rate, have trouble feeling your pulse, or think that keeping track of your heart rate is a bother, use the talk test or a perceived-exertion scale to monitor your exercise intensity.

Be FIT

You can design your own program by using the FIT approach. FIT stands for how often you exercise (F = Frequency), how hard you work (I = Intensity), and how long you exercise each day (T = Time). The guidelines recommend that you exercise at moderate intensity for a minimum of 150 minutes a week. You can build your exercise program by varying frequency, time, and activities. We are recommending moderate-intensity exercise, so you will start slowly and increase frequency and time as you work toward or even beyond 150 minutes each week. You can use different kinds or combinations of exercises. The following are programs of moderate intensity that reach 150 minutes each week:

A 10-minute walk at moderate intensity three times a day, 5 days a week

A 20-minute bike ride at moderate intensity (most on level ground) 3 days a week and a 30-minute walk 3 days a week

A 30-minute aerobic dance class at moderate intensity twice a week and three 10-minute walks 3 days a week

If you are just starting, you could begin like this:

Take a 5-minute walk around the house three times a day, 6 days a week (total = 90 minutes).

Take a 5-minute walk around the house three times a day, 6 days a week (total = 90 minutes).

Take a water aerobics class for 40 minutes twice a week and two 10-minute walks on 2 other days a week (total = 120 minutes).

Take a water aerobics class for 40 minutes twice a week and two 10-minute walks on 2 other days a week (total = 120 minutes).

Take a low-impact aerobic class once a week (50 minutes), mow the lawn for 30 minutes, and take two 20-minute walks (total = 120 minutes).

Take a low-impact aerobic class once a week (50 minutes), mow the lawn for 30 minutes, and take two 20-minute walks (total = 120 minutes).

An easy way to remember the guideline goal for minimum physical activity is that you should accumulate 30 minutes of moderate physical activity on most days of the week. This could be a combination of walking, stationary bicycling, dancing, swimming, or chores that require moderate-intensity activity. It is important to remember that 150 minutes is a goal, not necessarily your starting point. If you begin exercising just 2 minutes at a time, you are likely to be able to reach the recommended 10 minutes three times a day. Almost everyone can reach the guideline goals and achieve important health benefits. If you have a setback and stop exercising for a while, start back exercising for less time and less vigorously than when you stopped. It takes some time to work back up again; be patient with yourself.

Warming Up and Cooling Down

If you are going to exercise at moderate intensity, it is important to warm up first and cool down afterward.

Warming Up

Don’t exercise cold. Before building to moderate intensity, you must prepare your body to do more strenuous work. This means doing at least 5 minutes of a low-intensity activity to allow your muscles, heart, lungs, and circulation to gradually increase their work. If you are going for a brisk walk, warm up with 5 minutes of slow walking. If you are riding a stationary bike, warm up on the bike with 5 minutes of easy pedaling. In an aerobic exercise class, you will warm up with a gentle routine before getting more vigorous. Warming up reduces the risk of injuries, soreness, and irregular heartbeat.

Cooling Down

A cool-down period after moderate-intensity exercise helps your body return to its normal resting state. Repeating the 5-minute warm-up activity or taking a slow walk helps your muscles gradually relax and your heart and breathing slow down. Gentle flexibility exercises during the cool-down can be relaxing, and gentle stretching after exercise helps reduce muscle soreness and stiffness.

Aerobic (Endurance) Exercises

We will examine a few common low-impact aerobic exercises. All of these exercises can condition your heart and lungs, strengthen your muscles, relieve tension, and help you manage your weight. Most of these exercises can also strengthen your bones (swimming and aqua aerobics are the exceptions).

Walking

Walking is easy, inexpensive, and safe, and it can be done almost anywhere. You can walk by yourself or with company. Walking is safer than jogging or running and puts less stress on the body. It’s an especially good choice if you have been sedentary or have joint or balance problems.

If you walk to shop, visit friends, and do household chores, then you can probably walk for exercise. Using a cane or walker need not stop you from getting into a walking routine. If you are in a wheelchair, use crutches, or experience more than mild discomfort when you walk a short distance, you should consider some other type of aerobic exercise or consult a physician or therapist for help.

Be cautious the first two weeks of walking. If you haven’t been doing much for a while, 5 or 10 minutes may be enough. Alternate brisk walks and slow walks to build up your time. Each week increase the brisk walking interval by no more than 5 minutes until you are up to 20 or 30 minutes. Remember that your goal is to walk most days of the week, at moderate intensity, to get up to at least 10 minutes at a time. Before starting, read these walking tips.

Walking tips

Choose your ground. Walk on a flat, level surface. Walking on hills, uneven ground, soft earth, sand, or gravel is hard work and often leads to hip, knee, or foot pain. Fitness trails, shopping malls, school tracks, streets with sidewalks, and quiet neighborhoods are good places.

Choose your ground. Walk on a flat, level surface. Walking on hills, uneven ground, soft earth, sand, or gravel is hard work and often leads to hip, knee, or foot pain. Fitness trails, shopping malls, school tracks, streets with sidewalks, and quiet neighborhoods are good places.

Always warm up and cool down with a stroll. Walk slowly for 5 minutes to prepare your circulation and muscles for a brisker walk. Finish up with the same slow walk to let your body calm down gradually. Experienced walkers know they can avoid shin and foot discomfort if they begin and end with a stroll.

Always warm up and cool down with a stroll. Walk slowly for 5 minutes to prepare your circulation and muscles for a brisker walk. Finish up with the same slow walk to let your body calm down gradually. Experienced walkers know they can avoid shin and foot discomfort if they begin and end with a stroll.

Set your own pace. It takes practice to find the right walking speed. To find your speed, start walking slowly for a few minutes, then increase your speed to a pace that is slightly faster than normal for you. After 5 minutes, check your exercise intensity by using a perceived-exertion or talk test. If you are working too hard or feel out of breath, slow down. If you are below your desired intensity, try walking a little faster. Walk another 5 minutes and check your intensity again. If you are still below your target intensity, keep walking at a comfortable speed and simply check your intensity in the middle and at the end of each walk.

Set your own pace. It takes practice to find the right walking speed. To find your speed, start walking slowly for a few minutes, then increase your speed to a pace that is slightly faster than normal for you. After 5 minutes, check your exercise intensity by using a perceived-exertion or talk test. If you are working too hard or feel out of breath, slow down. If you are below your desired intensity, try walking a little faster. Walk another 5 minutes and check your intensity again. If you are still below your target intensity, keep walking at a comfortable speed and simply check your intensity in the middle and at the end of each walk.

Increase your arm work. You can use your arms to raise your heart rate into the target exercise range. (Note that many people with lung disease may want to avoid arm exercises, as they can cause more shortness of breath than other exercises.) Bend your elbows a bit, and swing your arms more vigorously. You might carry a 1- or 2-pound (0.5 or 1.0 kg) weight in each hand. You can purchase hand weights for walking; hold a can of food in each hand, or put sand, dried beans, or pennies in two small plastic beverage bottles or socks. The extra work you do with your arms increases your intensity of exercise without forcing you to walk faster than you find comfortable.

Increase your arm work. You can use your arms to raise your heart rate into the target exercise range. (Note that many people with lung disease may want to avoid arm exercises, as they can cause more shortness of breath than other exercises.) Bend your elbows a bit, and swing your arms more vigorously. You might carry a 1- or 2-pound (0.5 or 1.0 kg) weight in each hand. You can purchase hand weights for walking; hold a can of food in each hand, or put sand, dried beans, or pennies in two small plastic beverage bottles or socks. The extra work you do with your arms increases your intensity of exercise without forcing you to walk faster than you find comfortable.

Shoes

Wear shoes of the correct length and width with shock-absorbing soles and insoles. Make sure they’re big enough in the toe area. The rule of thumb is a thumb width between the end of your longest toe and the end of the shoe. You shouldn’t feel pressure on the sides or tops of your toes. The heel counter should hold your heel firmly in the shoe when you walk.

Wear shoes with a continuous composite sole. Be sure your shoes are in good repair. Shoes with laces or Velcro let you adjust width as needed and give more support than slip-ons. If you have problems tying laces, consider Velcro closures or elastic shoelaces. Shoes with leather soles and a separate heel don’t absorb shock as well as athletic and casual shoes. Good shoes do not need to be expensive; any shoes that meet the criteria we have just described will serve your purposes.

Many people like shoes with removable insoles that can be exchanged for more shock-absorbing ones. You can find insoles in sporting goods stores and shoe stores. When you shop for insoles, take your walking shoes with you. Try on the shoe with the insole inserted to make sure there’s still enough room for your foot to be comfortable. Insoles come in different sizes and can be trimmed with scissors for a custom fit. If your toes take up extra room, try the three-quarter insoles that stop just short of your toes. If you have prescribed inserts in your shoes already, ask your doctor about insoles.

Avoid purchasing shoes that are too heavy or that have very thick, rubbery, or sticky soles that may create a tripping hazard.

Possible problems

If you have pain around your shins when you walk, you may not be spending enough time warming up. Try some ankle exercises (Chapter 7, Exercises 24–26) before you start walking. Start your walk at a slow pace for at least 5 minutes. Keep your feet and toes relaxed.

Sore knees are another common problem. Fast walking puts more stress on knee joints. To slow your speed and keep your heart rate up, try doing more work with your arms, as described earlier. Do the knee strengthener and ready-go exercises (Chapter 7, Exercises 18 and 20) in your warm-up.

Cramps in the calf and pain in the heel can be reduced by starting with the Achilles stretch (Chapter 7, Exercise 22). A slow walk to warm up is also helpful. If you have circulation problems in your legs and get cramps or pain in your calves while walking, alternate between comfortably brisk and slow walking. Slow down and give your circulation a chance to catch up before the pain is so intense that you have to stop. As you will see, such exercises may even help you gradually walk farther with less cramping or pain. If this doesn’t help, check with your physician or therapist for suggestions.

Maintain good posture. Remember the heads-up position described in Chapter 7, and keep your shoulders relaxed to help reduce neck and upper back discomfort.

Swimming

Swimming is another good aerobic exercise. The buoyancy of the water lets you move your joints through their full range of motion and strengthen your muscles and cardiovascular system with less stress than on land. Because swimming involves the arms, it can lead to excessive shortness of breath. This is especially true for people with lung disease. However, for people with asthma, swimming may be the preferred exercise, as the moisture helps reduce shortness of breath. People with heart disease who have severely irregular heartbeats and have had an implantable defibrillator (AICD) should avoid swimming. For most people with chronic illness, however, swimming is excellent exercise. It uses the whole body. If you haven’t been swimming for a while, consider a refresher course.

To make swimming an aerobic exercise, you will eventually need to swim continuously for 10 minutes. Try different strokes, changing strokes after each lap or two. This lets you exercise all joints and muscles without overtiring any one area.

Note that although swimming is an excellent aerobic exercise, it does not improve balance, nor does it provide essential weight-bearing exercise for healthy bones. Incorporating swimming as one part of your overall fitness regime is recommended.

Swimming tips

The breast stroke and crawl normally require a lot of neck motion and may be uncomfortable. To solve this problem, use a mask and snorkel so that you can breathe without twisting your neck.

The breast stroke and crawl normally require a lot of neck motion and may be uncomfortable. To solve this problem, use a mask and snorkel so that you can breathe without twisting your neck.

Chlorine can be irritating to the eyes. Consider a good pair of goggles. You can even have swim goggles made in your eyeglass prescription.

Chlorine can be irritating to the eyes. Consider a good pair of goggles. You can even have swim goggles made in your eyeglass prescription.

A hot shower or soak in a hot tub after your workout helps reduce stiffness and muscle soreness. Remember not to work too hard or get too tired. If you’re sore for more than 2 hours, go easier next time.

A hot shower or soak in a hot tub after your workout helps reduce stiffness and muscle soreness. Remember not to work too hard or get too tired. If you’re sore for more than 2 hours, go easier next time.

Always swim where there are qualified lifeguards, if possible, or with a friend. Never swim alone.

Always swim where there are qualified lifeguards, if possible, or with a friend. Never swim alone.

Aquacize

If you don’t like to swim or are uncomfortable learning strokes, you can walk laps in the pool or join the millions who are “aquacizing”—exercising in water.

Aquacize is comfortable, fun, and effective as a flexibility, strengthening, and aerobic activity. The buoyancy of the water takes weight off the hips, knees, feet, and back. Because of this, exercise in water is generally better tolerated than walking by people who have pain in the hips, knees, feet, and back. Exercising in a pool allows you a degree of privacy in doing your own routine in that no one can see you much below shoulder level.

Getting started

Joining a water exercise class with a good instructor is an excellent way to get started. The Arthritis Foundation and the Y sponsor water exercise classes and train instructors to teach them. The heart and lung associations can refer you to exercise programs that include aquacize classes. Contact your local chapter or branch office to see what is available. Many community and private health centers also offer water exercise classes, some geared to older adults.

If you have access to a pool and want to exercise on your own, there are many water exercise books available that can guide you. Water temperature is always a concern when people talk about water exercise. The Arthritis Foundation recommends a pool temperature of 84°F (29°C), with the surrounding air temperature in the same range. Except in warm climates, this means a heated pool. If you’re just starting to aquacize, find a pool around this temperature. If you can exercise more vigorously and don’t have cold sensitivity, you can probably aquacize in cooler water. Many pools where people swim laps are about 80–83°F (27–28°C). It feels quite cool when you first get in, but starting off with water walking, jogging, or another whole-body exercise helps you warm up quickly.

The deeper the water you stand in, the less stress there is on joints; however, water above the chest can make it hard to keep your balance. You can let the water cover more of your body just by spreading your legs apart or bending your knees a bit.

Aquacize tips

Wear something on your feet to protect them from rough pool floors and to provide traction in the pool and on the deck. There is footgear especially designed to wear in the water. Some styles have Velcro straps to make them easier to put on. Beach shoes with rubber soles and mesh tops also work well.

Wear something on your feet to protect them from rough pool floors and to provide traction in the pool and on the deck. There is footgear especially designed to wear in the water. Some styles have Velcro straps to make them easier to put on. Beach shoes with rubber soles and mesh tops also work well.

If you are sensitive to cold or have Raynaud’s phenomenon, wear a pair of disposable latex surgical gloves. Boxes of gloves are available at most pharmacies. The water trapped and warmed inside the glove seems to insulate the hand. If your body gets cold in the water, wear a T-shirt or full-leg Lycra exercise tights for warmth.

If you are sensitive to cold or have Raynaud’s phenomenon, wear a pair of disposable latex surgical gloves. Boxes of gloves are available at most pharmacies. The water trapped and warmed inside the glove seems to insulate the hand. If your body gets cold in the water, wear a T-shirt or full-leg Lycra exercise tights for warmth.

If the pool does not have steps and it is difficult for you to climb up and down a ladder, suggest that pool staff position a three-step kitchen stool in the pool by the ladder rails. This is an inexpensive way to provide steps for easier entry and exit, and the steps are easy to remove and store when not needed.

If the pool does not have steps and it is difficult for you to climb up and down a ladder, suggest that pool staff position a three-step kitchen stool in the pool by the ladder rails. This is an inexpensive way to provide steps for easier entry and exit, and the steps are easy to remove and store when not needed.

Wearing a flotation belt or life vest adds extra buoyancy and comfort by taking weight off hips, knees, and feet.

Wearing a flotation belt or life vest adds extra buoyancy and comfort by taking weight off hips, knees, and feet.

As on land, moving slower makes your exercise easier. Another way to regulate exercise intensity is to change how much water you push when you move. For example, when you move your arms back and forth in front of you under water, it is hard work if you hold your palms facing each other and clap. It is easier if you turn your palms down and slice your arms back and forth with only the narrow edge of your hands pushing against the water.

As on land, moving slower makes your exercise easier. Another way to regulate exercise intensity is to change how much water you push when you move. For example, when you move your arms back and forth in front of you under water, it is hard work if you hold your palms facing each other and clap. It is easier if you turn your palms down and slice your arms back and forth with only the narrow edge of your hands pushing against the water.

Be aware that additional buoyancy allows for greater joint motion than you are probably used to, especially if you are exercising in a warm pool. Start slowly and do not overextend your time in the pool because it feels good until you know how your body will react or feel the next day.

Be aware that additional buoyancy allows for greater joint motion than you are probably used to, especially if you are exercising in a warm pool. Start slowly and do not overextend your time in the pool because it feels good until you know how your body will react or feel the next day.

If you have asthma, exercising in water can help you avoid the worsening of asthma symptoms that occurs during other types of exercise. This is probably due to the beneficial effect of water vapor on the lungs. Remember, though, that for many people with lung disease, exercises involving the arms can cause more shortness of breath than leg exercises. You may want to focus most of your aquacizing, therefore, on exercises involving mainly the legs.

If you have asthma, exercising in water can help you avoid the worsening of asthma symptoms that occurs during other types of exercise. This is probably due to the beneficial effect of water vapor on the lungs. Remember, though, that for many people with lung disease, exercises involving the arms can cause more shortness of breath than leg exercises. You may want to focus most of your aquacizing, therefore, on exercises involving mainly the legs.

If you have had a stroke or have another condition that may affect your strength and balance, make sure that you have someone to help you in and out of the pool. Finding a position close to the wall or staying close to a buddy who can lend a hand if needed are ways to add to your safety and security. You may even wish to sit on a chair in fairly shallow water as you do exercises. Ask the instructor to help you design the best exercise program, equipment, and facilities for your specific needs.

If you have had a stroke or have another condition that may affect your strength and balance, make sure that you have someone to help you in and out of the pool. Finding a position close to the wall or staying close to a buddy who can lend a hand if needed are ways to add to your safety and security. You may even wish to sit on a chair in fairly shallow water as you do exercises. Ask the instructor to help you design the best exercise program, equipment, and facilities for your specific needs.

Stationary Bicycling

Stationary bicycles offer the fitness benefits of bicycling without the outdoor hazards. They’re better for people who don’t have the flexibility, strength, or balance to be comfortable pedaling and steering on the road. Some people with paralysis of one leg or arm can exercise on stationary bicycles with special attachments for their paralyzed limb. Indoor use of stationary bicycles may also be preferable to outdoor bicycling for people who live in a cold or hilly area.

The stationary bicycle is a particularly good alternative exercise. It doesn’t put excess strain on your hips, knees, and feet; you can easily adjust how hard you work; and weather doesn’t matter. Use the bicycle on days when you don’t want to walk or do more vigorous exercise or when you can’t exercise outside.

Making it interesting

The most common complaint about riding a stationary bike is that it’s boring. If you ride while watching television, reading, or listening to music, you can become fit without becoming bored. One woman keeps interested by mapping out tours of places she would like to visit and then charts her progress on a map as she rolls off the miles. Other people set their bicycle time for the half hour of soap opera or news that they watch every day. There are also videocassettes and DVDs of exotic bike tours that put you in the rider’s perspective. Book racks that clip onto the handlebars make reading easy.

Riding tips

Stationary bicycling uses different muscles than walking. Until your leg muscles get used to pedaling, you may be able to ride for only a few minutes. Start off with no resistance. Increase resistance slightly as riding gets easier. Increasing resistance has the same effect as bicycling up hills. If you use too much resistance, your knees are likely to hurt, and you’ll have to stop before you get the benefit of endurance.

Stationary bicycling uses different muscles than walking. Until your leg muscles get used to pedaling, you may be able to ride for only a few minutes. Start off with no resistance. Increase resistance slightly as riding gets easier. Increasing resistance has the same effect as bicycling up hills. If you use too much resistance, your knees are likely to hurt, and you’ll have to stop before you get the benefit of endurance.

Pedal at a comfortable speed. For most people, 50 to 70 revolutions per minute (rpm) is a good place to start. Some bicycles tell you the rpm rate, or you can count the number of times your right foot reaches its lowest point in a minute. As you get used to bicycling, you can increase your speed. However, faster is not necessarily better. Listening to music at the right tempo makes it easier to pedal at a consistent speed. Experience will tell you the best combination of speed and resistance.

Pedal at a comfortable speed. For most people, 50 to 70 revolutions per minute (rpm) is a good place to start. Some bicycles tell you the rpm rate, or you can count the number of times your right foot reaches its lowest point in a minute. As you get used to bicycling, you can increase your speed. However, faster is not necessarily better. Listening to music at the right tempo makes it easier to pedal at a consistent speed. Experience will tell you the best combination of speed and resistance.

Set your goal at 20 to 30 minutes of pedaling at a comfortable speed. Build up your time by alternating intervals of brisk pedaling with less exertion. Use your heart rate or the perceived exertion talk test to make sure you aren’t working too hard. If you’re alone, reciting poems or telling a story to yourself as you pedal can make the time pass more quickly. If you get out of breath, slow down.

Set your goal at 20 to 30 minutes of pedaling at a comfortable speed. Build up your time by alternating intervals of brisk pedaling with less exertion. Use your heart rate or the perceived exertion talk test to make sure you aren’t working too hard. If you’re alone, reciting poems or telling a story to yourself as you pedal can make the time pass more quickly. If you get out of breath, slow down.

Keep a record of the times and distances of your bike trips. You’ll be amazed at how much you can do.

Keep a record of the times and distances of your bike trips. You’ll be amazed at how much you can do.

On bad days, maintain your exercise habit by pedaling with no resistance, at a lower rpm, or for a shorter period of time.

On bad days, maintain your exercise habit by pedaling with no resistance, at a lower rpm, or for a shorter period of time.

Other Exercise Equipment

If you have trouble getting on or off a stationary bicycle or don’t have room for a bicycle where you live, you might try a restorator or arm crank. Ask your therapist or doctor, or call a medical supply house.

A restorator is a small piece of equipment with foot pedals that can be attached to the foot of a bed or placed on the floor in front of a chair. It allows you to exercise by pedaling. Resistance can be varied, and placement of the restorator lets you adjust for leg length and knee bend. A restorator can be a good alternative to an exercise bicycle for people who have problems with balance, weakness, or paralysis. People with other chronic illnesses, such as lung disease, may find the restorator to be an enjoyable way to start an exercise program.

Arm cranks or arm ergometers are bicycles for the arms. They are mounted on a table. People who are unable to use their legs for active exercise can improve their cardiovascular fitness and upper body strength by using the arm crank. It’s important to work closely with a physical therapist to set up your program, because using only your arms for endurance exercise requires different intensity monitoring than using the bigger leg muscles. As mentioned previously, many people with lung disease may find arm exercises to be less enjoyable than leg exercises because they may experience shortness of breath.

There are many other types of exercise equipment. These include treadmills, self-powered and motor-driven rowing machines, cross-country skiing machines, mini-trampolines, and stair-climbing and elliptical machines. Most are available in both commercial and home models. If you’re thinking about exercise equipment, know what you want to achieve. For cardiovascular fitness and endurance, you want equipment that will help you exercise as much of your body at one time as possible. The motion should be rhythmic, repetitive, and smooth. The equipment should be comfortable, safe, and not stressful on joints. If you’re interested in a new piece of equipment, try it out for a week or two before buying.

Exercise equipment that requires you to use weights usually does not improve cardiovascular fitness unless individualized circuit training can be designed. Most people will find that the flexibility and strengthening exercises in this book will help them safely achieve significant increases in strength as well as flexibility. Be sure that you consult with your doctor, therapist, or trained fitness instructor if you want to add strengthening exercises involving weights or weight machines to your program.

Low-Impact Aerobics

Most people find low-impact aerobic dance a fun and safe form of exercise. “Low impact” means that one foot is always on the floor and there is no jumping. However, low impact does not necessarily mean low intensity, nor do the low-impact routines protect all joints. If you participate in a low-impact aerobics class, you’ll probably need to make some changes to suit your needs. You can also get low-impact aerobic exercise in classes that include dancing such as Zumba or Jazzercise. Regular dancing such as salsa, ballroom, and square dancing also provide good aerobic exercise.

Getting Started

Let the instructor know who you are, that you may modify some movements to meet your needs, and that you may need to ask for advice. It’s easier to start off with a newly formed class than it is to join an ongoing class. If you don’t know people, try to get acquainted. Be open about why you may sometimes do things a little differently. You’ll be more comfortable and may find others who also have special needs.

Most instructors use music or count to a specific beat and do a set number of repetitions. You may find that the movement is too fast or that you don’t want to do as many repetitions. Modify the routine by moving to every other beat or keeping up with the beat until you start to tire and then slowing down or stopping. If the class is doing an exercise that involves arms and legs and you get tired, try resting your arms and doing only the leg movements or just walking in place until you are ready to go again. Most instructors will be able to instruct you in “chair aerobics” if you need some time off your feet.

Some low-impact routines use a lot of arm movements done at or above shoulder level to raise the heart rate. Remember that for people with lung disease, hypertension, or shoulder problems, too much arm exercise above shoulder level can worsen shortness of breath, increase blood pressure, or cause pain. Modify the exercise by lowering your arms or taking a rest break.

Being different from the group in a room walled with mirrors takes courage, conviction, and a sense of humor. The most important thing you can do for yourself is to choose an instructor who encourages everyone to exercise at her or his own pace and a class where people are friendly and having fun. Observe classes, speak with instructors, and participate in at least one class session before making any financial commitment.

Aerobics tips

Wear shoes. Many studios have cushioned floors and soft carpet that might tempt you to go barefoot. Don’t! Shoes help protect the small joints and muscles in your feet and ankles by providing a firm, flat surface on which to stand.

Wear shoes. Many studios have cushioned floors and soft carpet that might tempt you to go barefoot. Don’t! Shoes help protect the small joints and muscles in your feet and ankles by providing a firm, flat surface on which to stand.

Protect your knees. Stand with knees straight but relaxed. Many low-impact routines are done with bent, tensed knees and a lot of bobbing up and down. This can be painful and is unnecessarily stressful. Avoid this by remembering to keep your knees relaxed (aerobics instructors call this “soft knees”). Watch in the mirror to see that you keep the top of your head steady as you exercise. Don’t bob up and down.

Protect your knees. Stand with knees straight but relaxed. Many low-impact routines are done with bent, tensed knees and a lot of bobbing up and down. This can be painful and is unnecessarily stressful. Avoid this by remembering to keep your knees relaxed (aerobics instructors call this “soft knees”). Watch in the mirror to see that you keep the top of your head steady as you exercise. Don’t bob up and down.

Don’t overstretch. The beginning (warm-up) and end (cool-down) of the session will have stretching and strengthening exercises. Remember to stretch only as far as you comfortably can. Hold the position, and don’t bounce. If the stretch hurts, don’t do it. Instead, ask your instructor for a less stressful substitute, or choose one of your own.

Don’t overstretch. The beginning (warm-up) and end (cool-down) of the session will have stretching and strengthening exercises. Remember to stretch only as far as you comfortably can. Hold the position, and don’t bounce. If the stretch hurts, don’t do it. Instead, ask your instructor for a less stressful substitute, or choose one of your own.

Change movements. Do this often enough that you don’t get sore muscles or joints. It’s normal to feel some new sensations in your muscles and around your joints when you start a new exercise program. However, if you feel discomfort doing the same movement for some time, change movements or stop for a while and rest.

Change movements. Do this often enough that you don’t get sore muscles or joints. It’s normal to feel some new sensations in your muscles and around your joints when you start a new exercise program. However, if you feel discomfort doing the same movement for some time, change movements or stop for a while and rest.

Alternate kinds of exercise. Many exercise facilities have a variety of exercise opportunities: equipment rooms with cardiovascular machines, pools, and aerobics studios. If you have trouble with an hour-long aerobics class, see if you can join the class for the warm-up and cool-down and use a stationary bicycle or treadmill for your aerobics portion. Many people have found that this routine gives them the benefits of both an individualized program and group exercise.

Alternate kinds of exercise. Many exercise facilities have a variety of exercise opportunities: equipment rooms with cardiovascular machines, pools, and aerobics studios. If you have trouble with an hour-long aerobics class, see if you can join the class for the warm-up and cool-down and use a stationary bicycle or treadmill for your aerobics portion. Many people have found that this routine gives them the benefits of both an individualized program and group exercise.

Self-Tests for Endurance (Aerobic Fitness)

For some people, just the feelings of increased endurance and well-being are enough to indicate progress. Others may need proof that their exercise program is making a measurable difference. You can use one or both of these endurance or aerobic fitness tests. Not everyone will be able to do both tests, so pick one that works best for you. Record your results. After 4 weeks of exercise, repeat the test and check your improvement. Measure yourself again after 4 more weeks.

Testing by Distance

Use a pedometer. One of the least expensive pieces of equipment is a pedometer. Because distance can be difficult to set, the best pedometers measure your steps. If you get in the habit of wearing a pedometer, it is easy to motivate yourself to add a few extra steps each day. You will be surprised at how these add up.

Use a pedometer. One of the least expensive pieces of equipment is a pedometer. Because distance can be difficult to set, the best pedometers measure your steps. If you get in the habit of wearing a pedometer, it is easy to motivate yourself to add a few extra steps each day. You will be surprised at how these add up.

Measure distance. Find a place to walk, bicycle, swim, or water-walk where you can measure distance. A running track works well. On a street you can measure distance with a car. A stationary bicycle with an odometer provides the same measurement. If you plan on swimming or water-walking, you can count lengths of the pool. After a warm-up, note your starting point and then bicycle, swim, or walk as briskly as you comfortably can for 5 minutes. Try to move at a steady pace for the full time. At the end of 5 minutes, mark your spot or note the distance or number of laps, and immediately take your pulse or rate your perceived exertion from 0 to 10. Continue at a slow pace for 3 to 5 more minutes to cool down. Record the distance, your heart rate, and your perceived exertion.

Measure distance. Find a place to walk, bicycle, swim, or water-walk where you can measure distance. A running track works well. On a street you can measure distance with a car. A stationary bicycle with an odometer provides the same measurement. If you plan on swimming or water-walking, you can count lengths of the pool. After a warm-up, note your starting point and then bicycle, swim, or walk as briskly as you comfortably can for 5 minutes. Try to move at a steady pace for the full time. At the end of 5 minutes, mark your spot or note the distance or number of laps, and immediately take your pulse or rate your perceived exertion from 0 to 10. Continue at a slow pace for 3 to 5 more minutes to cool down. Record the distance, your heart rate, and your perceived exertion.

Repeat the test after several weeks of exercise. There may be a change in as soon as 4 weeks. However, it often takes 8 to 12 weeks to see improvement.

Repeat the test after several weeks of exercise. There may be a change in as soon as 4 weeks. However, it often takes 8 to 12 weeks to see improvement.

Goal: To cover more distance, to lower your heart rate, or to lower your perceived exertion.

Testing by Time

Set a time. Measure a given distance to walk, bike, swim, or water-walk. Estimate how far you think you can go in 1 to 5 minutes. You can pick a number of blocks, actual distance, or lengths in a pool. Spend 3 to 5 minutes warming up. Start timing and begin moving steadily, briskly, and comfortably. At the finish, record how long it took you to cover your course, your heart rate, and your perceived exertion.

Set a time. Measure a given distance to walk, bike, swim, or water-walk. Estimate how far you think you can go in 1 to 5 minutes. You can pick a number of blocks, actual distance, or lengths in a pool. Spend 3 to 5 minutes warming up. Start timing and begin moving steadily, briskly, and comfortably. At the finish, record how long it took you to cover your course, your heart rate, and your perceived exertion.

Repeat the test after several weeks of exercise, as you would for distance.

Repeat the test after several weeks of exercise, as you would for distance.

Goal: To complete the distance in less time, at a lower heart rate, or at a lower perceived exertion.

Suggested Further Reading

Fortmann, Stephen P., and Prudence E. Breitrose. The Blood Pressure Book: How to Get It Down and Keep It Down, 3rd ed. Boulder, Colo.: Bull, 2006.

Karpay, Ellen. The Everything Total Fitness Book. Avon, Mass.: Adams Media, 2000.

Knopf, Karl. Make the Pool Your Gym: No-Impact Water Workouts for Getting Fit, Building Strength and Rehabbing from Injury. Berkeley, Calif.: Ulysses Press, 2012

Nelson, Miriam E, Alice H. Lichtenstein, and Lawrence Lindner. Strong Women, Strong Hearts: Proven Strategies to Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease Now. New York: Putnam, 2005.

White, Martha. Water Exercise: 78 Safe and Effective Exercises for Fitness and Therapy. Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics, 1995.

Other Resources

Sit and Be Fit (chair exercise): http://www.sitandbefit.org

Sit and Be Fit (chair exercise): http://www.sitandbefit.org

Frequency is how often you exercise. Most guidelines suggest doing at least some exercise most days of the week. Three to five times a week is a good choice for moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Taking every other day off gives your body a chance to rest and recover.

Frequency is how often you exercise. Most guidelines suggest doing at least some exercise most days of the week. Three to five times a week is a good choice for moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Taking every other day off gives your body a chance to rest and recover.

Sit and Be Fit (chair exercise):

Sit and Be Fit (chair exercise):