| ∎ | 6 | ∎ |

Organization is central to collective action, yet organizational resources vary greatly. Institutionalized civil-society organizations are an important presence in many contemporary societies but were largely absent in the PRC until fairly recently.1 From the Red Guard movement to the student movement in 1989, schools and work units provided the essential social basis for movement organization.2 Activists appropriated state-designed organizational structures and turned them into resources for mobilization. Although independent movement organizations appeared in the middle of these movements, they ceased to exist with the suppression of the movements, and no legitimate nonstate organizational basis ultimately developed. Social organizations grew rapidly in the 1980s, but as the case of the Chinese Economic System Reform Research Institute (SRI) illustrates, they were mostly state sponsored. Their approach to social and political change was to work from within the establishment.3

In the early 1990s, voluntary organizing began to revive, this time in a new direction marked by the appearance of new types of grassroots civic associations. Compared with social organizations in the 1980s,4 these new organizations have achieved a new degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the state.5 They are also more diverse in form, ranging from officially registered civic organizations to informal grassroots associations, student associations, leisure clubs, support groups and, with the diffusion of the Internet, new digital formations such as online communities. These civic associations provide the organizational basis for the new citizen activism since the 1990s.

I will study two major types of new civic associations. One is civic associations, the other is online communities. The first type exists primarily offline; the second relies more heavily, but not solely, on the Internet. These two types raise two somewhat different sets of questions concerning their relations with online activism. With respect to online communities, the main questions are why people join them and how they generate contention. I will address these questions in the next chapter. This chapter focuses on civic organizations and examines (1) the extent to which they have incorporated the Internet into their agendas and (2) the mutually constitutive relations between organizations and technology. To answer these questions requires a basic understanding of civic organizations’ Internet capacity and patterns of Internet use. Are they online in the first place? How do they use the Internet in their daily operations? With what impact on organizational development? I will answer these questions through an analysis of survey data I collected from October 2003 to January 2004.

The survey yields four main findings. First, urban grassroots organizations are equipped with a minimal level of Internet capacity. Second, for these organizations, the Internet is most useful for publicity work, information dissemination, and networking with peer and international organizations. Third, social-change organizations, younger organizations, and organizations in Beijing report more use of the Internet than business associations, older organizations, and organizations outside Beijing. Fourth, organizations with bare-bones Internet capacity report more active use of the Internet than better-equipped organizations. These findings suggest that the Internet has had a special appeal to relatively new organizations oriented to social change and that a “web” of civic associations has emerged in China. Following the survey analysis, I will present four case studies of Web-based environmental groups to illustrate how grassroots citizen groups have sought social change and organizational development through the use of the Internet.

A Tale of Two Revolutions: Information and Association

While the Internet caught on in China, another social trend was gathering force: the revival of voluntary associations. In the 1980s, social organizations had already multiplied, but after the suppression of the student movement in 1989, the number of newly formed organizations fell drastically.6 Further, the revival of voluntary associations in the 1990s had some new features. The most important feature is the appearance of large numbers of organizations oriented to social service and social change. Pei’s study finds that although business and trade associations flourished in the 1980s, there was a dearth of public-affairs organizations then.7 Jude Howell observes that from the early to mid-1990s onward, there was “a new wind in civil society,” that is, the rapid growth of associations concerned with providing services to marginalized groups such as migrant workers and HIV/AIDS patients.8 She concludes that the corporatist framework for analyzing Chinese civic organizations can no longer capture the “increasingly diverse and differentiated reality”9 of civic organizing in China. The works of several other scholars support this argument. Some have argued that such organizations have achieved a new degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the state.10 Others have shown that unlike organizations in the “state corporatism” model, the rural NGO they studied “is not a creature of either the central or local government” but “a genuine minjian association, created by and operated for the benefit of the local community.”11 Environmental NGOs provide further evidence of this “new wind in civil society.”12

If the advent of the Internet inaugurates an information revolution in China, then the rise of new types of voluntary associations marks an associational revolution.13 In appearance, these two phenomena are not necessarily related. People everywhere have associated with or without modern transportation and communication technologies. Does the Internet matter?

In many parts of the world, civil-society actors were early adopters of the Internet because of a high degree of elective affinity between Internet culture and civil-society culture.14 Some have postulated that horizontal communication and the sharing of information as public goods are two distinct features of civil-society organizations and new information and communication technologies.15 Social-science research on the adoption of new ICTs generally supports the hypothesis that civil-society organizations embrace the Internet because it is an affordable and effective communication technology. Some scholars find that the use of such technologies can reconfigure information flows and relationships.16 Others have shown that in transitional societies such as Eastern Europe, civil-society use of new ICTs leads to organizational innovation.17 Still others have focused on how civil-society organizations use the Internet to promote social causes.18 A common message is that the Internet matters to civic organizations. Technological change may provide new opportunities and resources for organizational development and institutional transformation.

Current social-science research has thus taken into account organizational and ecological conditions that influence the use of the Internet by civic associations. It commonly assumes that civic associations operate in an open and democratic environment. The same assumption is often extended to the Internet. Yet these two assumptions do not hold in China, where the state attempts to control both the Internet and civic associations. How does the Chinese political context shape the relationship between the Internet and civil-society organizations?

Politics is an inescapable fact of life for Chinese civic associations. It influences civic associations through two key mechanisms. One mechanism of influence is to set the rules of the game for civic associations. The other is to charge state agencies with the task of monitoring and implementing these rules. There are both general and specific rules of the game. The most “sacred” general rule is “the principle of Party supremacy,” mentioned in chapter 2. This principle is useful for understanding the political challenge facing Chinese civic associations. It means, in slightly different terms, that the Chinese party-state may allow the growth of civic associations provided that they do not challenge the legitimacy of the party-state. When civic associations are perceived to have posed threats to the party-state, political control may be tightened.

In essence, the rule of “party supremacy” puts all civic associations in subordinate positions vis-à-vis the party-state. In practice, it translates into a state-corporatist framework for the management of civic associations. State-corporatist argument holds that the state permits the development of social organizations, such as NGOs, provided that they are licensed by the state and observe state controls on the selection of leaders and articulation of demands.19 In 1995, Unger and Chan made a strong case for a state-corporatist perspective on Chinese society based on observations of social organizational development in the 1980s.20 Since then, however, significant changes have taken place. New types of civil-society organizations have appeared that are independent of the state in funding, personnel appointment, and administration.21 Although the relationship between civic associations and the state remains one of subordination and domination, the contents and dynamics of this relationship have become more complex.

First, again as mentioned in chapter 2, the state is not a homogeneous entity but a complex system of multilevel party organizations and government agencies. It faces not only enormous challenges in policy implementation but also intraparty and intragovernmental conflicts of interest and turf battles. For example, the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA) may disapprove of a dam-building project for environmental reasons, but the State Economic and Development Commission may give the project the green light because economic development is its priority. Furthermore, Chinese politics has an informal dimension, and state bureaucracies are open to personal influences.22 The heterogeneity of the Chinese state and the informal facet of Chinese politics translate into opportunities for Chinese civic associations. Environmental NGOs, for example, have found some SEPA officials to be strong allies, just as these SEPA officials sometimes depend on environmental groups to speak out on issues that they themselves hesitate to talk about publicly out of consideration for their relations with other government departments.

Second, just as Chinese civic associations are not autonomous from the Chinese party-state, so the party-state itself is not immune to externalities. In the 1990s, these external conditions included society itself, globalization, the market, and the information revolution. Scholars of comparative politics have argued that “societies affect states as much as, or possibly more than, states affect societies.”23 Third, civic associations themselves are strategic social actors. As subordinate groups in an unstable and fledgling new field, they “take what the system will give to avoid dominant groups in stable fields” in order “to keep their group together and their hopes of challenging alive.”24 They can make strategic use of their relations with the party-state to negotiate the state and seek organizational development.25 In addition, they can mobilize other resources to promote organizational development.

Chinese Civic Associations Respond to the Internet

For Chinese civic associations, one of the consequences of its subordinate position vis-à-vis the state is that they must seek resources and support from other social fields to negotiate state power. The Internet presents a vast network of information and communication. It is a new field from which civic associations can potentially draw strength. Despite the growing amount of research on the Chinese Internet, little attention has been paid to how civic associations respond to the Internet.26

To understand how well or poorly civic associations are equipped with the Internet and how they use it, namely their Internet capacity and Internet use, I conducted a survey of a sample of 550 urban civic associations from October 2003 through January 2004.27 An urban focus was necessary, because Internet use in rural areas remained marginal at the time of the survey. I used a proxy measure of Internet capacity by adapting an informatization index used by the International Telecommunication Union to measure the development of telecommunications technology at the national level.28 This informatization index distinguishes information technology (IT) from telephones and cellular phones and measures national-level IT development by the number of personal computers, computer hosts,29 and Internet users. Adapting this index to the organizational level, I use four indicators to measure an organization’s Internet capacity: number of computers, number of computer hosts, proportion of computers to staff, and proportion of computer hosts to staff.30 My survey sample consisted of 550 organizations. The response rate was 25 percent, yielding a valid sample of 138 civic organizations. After diagnostics, nine extreme cases were detected and removed from the sample.31 The remaining 129 cases were the basis of my analysis. These 129 cases encompass all the main types of civic associations in China. I grouped them into five broad categories: (1) business associations, (2) environment, (3) women, (4) social services, health, and community development, and (5) others (for example, religious and cultural organizations). Reflecting the broad trend in the development of civic associations, the largest category is business associations, numbering fifty-six out of 129. These are primarily trade associations and chambers of commerce. Also reflecting a new trend since the 1990s, the sample has sixteen environmental organizations, accounting for a relatively high 12 percent of the sample.

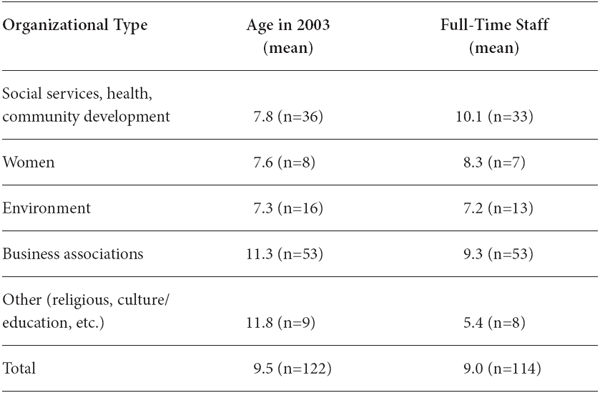

The sampled organizations are relatively young, mostly founded since the 1990s. As of 2003, they have an average organizational age of nine-and-a-half. Eighty-two (67 percent) of 122 organizations with information about their organization’s age were founded in or after 1991. Only seven organizations were founded in or before 1984. Most of the organizations are modest in size, with an average of nine full-time staff members. One hundred out of 112 organizations with registration information are officially registered, accounting for 89 percent of the sample; twelve (11 percent) are not registered. Table 6.1 presents the average age and number of full-time staff by organizational type.

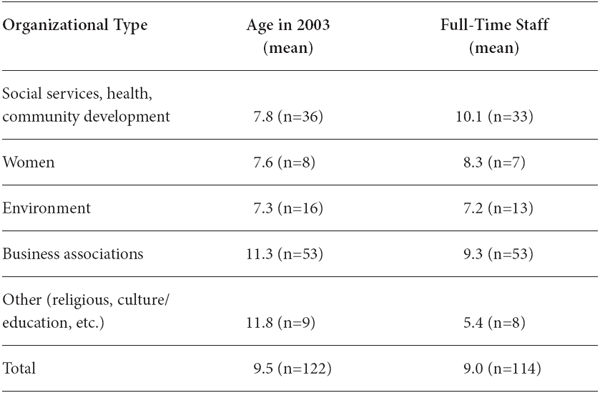

My survey captures three modes of growth of civic associations since the founding of the PRC. They are 1988, 1993, and 2000–2002. Ten out of 122 organizations were founded in 1988, eleven in 1993, and twenty-seven between 2000 and 2002. They account for 39 percent of the sample. The first mode of growth is consistent with the findings in Minxin Pei’s study. Covering the years from 1979 to 1992, Pei’s study finds that 1981, 1988, and 1989 saw the most visible gains in the number of newly formed associations, whereas 1983 and 1990 saw drastic drops in the number.32 While organizations established in the first wave of growth (1981) in Pei’s study are underrepresented in my study, my sample captures Pei’s second phase (1988 and 1989) well. Furthermore, my sample captures new trends that appeared after 1992, the cut-off point for Pei’s data. As figure 6.1 shows, the number of newly founded civic associations began to increase again in 1993. The growth remained robust throughout the 1990s until peaking in 2002. This pattern resembles that found in a study by Shaoguang Wang and Jianyu He.33 One difference is that the slump in the number of newly founded organizations between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s in the Wang and He study occurred later than that in our study. This may be because my sample includes twelve (11 percent) unregistered organizations, whereas the Wang and He study samples only registered organizations. As Wang and He note, the Chinese government implemented more stringent criteria for renewing and registering organizations in 1998. This may have led to a decline in the number of registered associations but not necessarily unregistered ones.

TABLE 6.1 Organizational Age and Number of Full-Time Staff by Types of Civic Associations, December 2003

Minxin Pei attributes the drastic growth of civic associations in 1988 and 1989 to the relatively relaxed political climate in 1988.34 Pei also finds that of all types of civic associations, trade and business associations were growing the fastest in number, reflecting the deepening of market reforms. The first wave of growth of civic associations in our sample was due to structural processes similar to those identified in Pei’s study. Those organizations founded in 1988 in our sample existed in the same political climate as those in Pei’s sample. Also similar to Pei’s study, the number of business associations founded in 1988 was relatively large: six out of ten.

On average, the nonbusiness associations in my sample are younger than the business associations. They are more likely to have been founded in the 1990s and after. Pei’s study finds that although business and trade associations flourished in the 1980s, there was a dearth of public-affairs organizations then.35 Jude Howell observes that from the early to mid-1990s onward, the most notable development in Chinese civil society was the rapid growth of associations concerned with providing services to marginalized groups.36 My study supports both Pei’s finding and Howell’s observation.

FIGURE 6.1 Chinese Civic Associations Founded by Year, 1951–2003 (percent, n=122)

Several domestic and international factors may explain the jump in the number of new civic associations in 1993 and the relatively stable growth thereafter. Internationally, the 1995 UN World Conference on Women in Beijing had a significant impact on the growth of NGOs in China, especially women’s organizations.37 The growing presence of international NGOs in China is another source of influence. Jude Howell argues, for example, that “external agencies have played a much greater role in the nurturing of civil society and public spheres than has been previously understood in China.”38 Keith, Lin, and Huang similarly point to the importance of international contacts for the development of local NGOs.39

On the domestic front, as Howell argues, the deepening of the market reform following Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992 bankrupted the socialist welfare system and created a large, marginalized population badly in need of social support.40 This structural change necessitated the rise of new social-service organizations. We may add that, in the case of environmental groups, which make up 12 percent of my sample, the acceleration of the market reform in the 1990s was accompanied by severe environmental degradation. The appearance of grassroots environmental groups was at least partially a response to China’s environmental crisis. Furthermore, the development of the Internet, which parallels the revival of civic associations, is another favorable condition. As the following analysis will show, the Internet is more than a technological tool; it is a strategic resource and opportunity for small and resource-poor organizations to stake out an existence in China’s constraining political context.

Internet Capacity of Chinese Civic Associations

To be able to use the Internet requires basic capabilities such as computer equipment. Although some observers have argued that in many industrialized societies, Internet access is no longer a main issue for civil-society organizations,41 it remains a challenge for organizations in developing countries. A digital divide is still a serious barrier. China has a numerically large but proportionally small Internet population; less than 10 percent of its population was online at the time of the survey. The majority are still left behind in the Internet age.42 Therefore, a starting point for understanding how Chinese civic associations respond to the Internet is their basic Internet capacity. Does the average association have computers? Are they linked to the Internet? How many staff members share a computer?

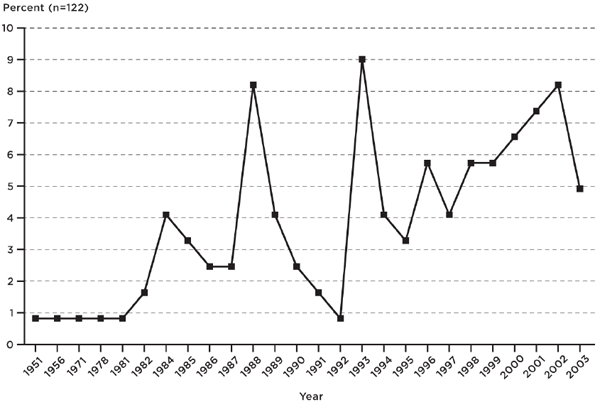

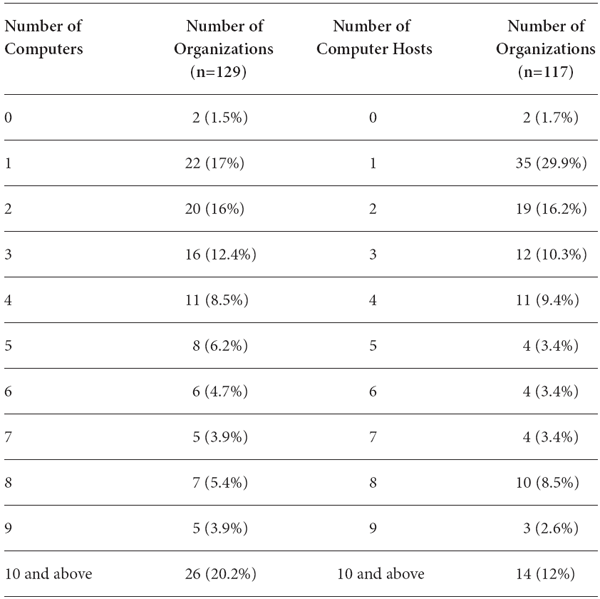

Our survey shows that Chinese civic associations have a minimal level of Internet capacity. On average, each organization has close to six computers and about five of these are linked to the Internet. In terms of methods of connection, forty-three (36 percent) out of 119 organizations report using dialup, fifty-two (43.7 percent) report using broadband, and twenty-four (20 percent) report using both dialup and broadband. Only two out of 129 organizations do not own a computer. About half (sixty) have three or fewer computers while twenty-two (17 percent) have one computer only. Table 6.2 shows the number of computers and computer hosts in Chinese civic associations.

The proportion of computers and computer hosts to the number of staff is low. On average, nearly two full-time staff members share one computer or computer host. The proportion becomes even lower if part-time staff is added. The average number of full-time staff for all organizations is about nine, that of full-time and part-time staff combined is about nineteen. This means that on average, more than three staff members (full and part-time) share one computer and every four people share a computer host. This is lower than the proportion of computer hosts to the number of Internet users at the national level for the same period. Nationally, of those who use the Internet for at least one hour per week, every two-and-a-half share a computer host.43

TABLE 6.2 Number of Computers and Computer Hosts in Chinese Civic Associations, December 2003

Chinese civic associations have an Internet capacity comparable to civic associations in other developing nations but lag behind organizations in developed countries. Data compiled in 2001 by Mark Surman show that as of 2000, 97 percent of voluntary organizations and small businesses in Britain already had Internet access and 87 percent of the voluntary organizations in the United States had Web sites.44 Although Surman provides no statistics on the actual number of computers or computer hosts, his measures of Internet access include up-to-date computers and dialup or high-speed Internet connections. The high rate of Internet access in the voluntary organizations he examined leads him to conclude that “basic Internet connection and access issues are no longer a major issue for most voluntary organizations.”45

Studies of voluntary organization in Latin America, Africa, and southeastern Europe show lower levels of Internet capacity than those in the United States and Britain. For example, a study of one hundred gender-equality organizations in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico finds that one-third of the organizations have no computer, one computer for the organization, or use home computers for their work. Forty-two percent of the organizations do not have all their computers connected to the Internet.46 A study of ICT use in seventy-eight civil-society organizations in Buenos Aires, Argentina, finds that only one-third of the organizations have Internet connections, with an average of five computers per organization. The same article also studies sixty NGOs in Montevideo, Uruguay, and finds that 87 percent of the organizations have at least one computer, and 60 percent have Internet connections.47 Finally, a study of six regions in southeastern Europe conducted in 2001 finds that despite unevenness in ICT capacity across the region, almost all the NGOs in the study have at least one computer, although only about 9 percent of them have Web sites.48 In comparative perspective, then, Chinese civic associations are neither at the head of the curve in terms of Internet capacity nor are they far behind. They have a minimal level of Internet capacity comparable to civic associations in other developing countries.

Internet Connectivity and Frequently Used Network Services

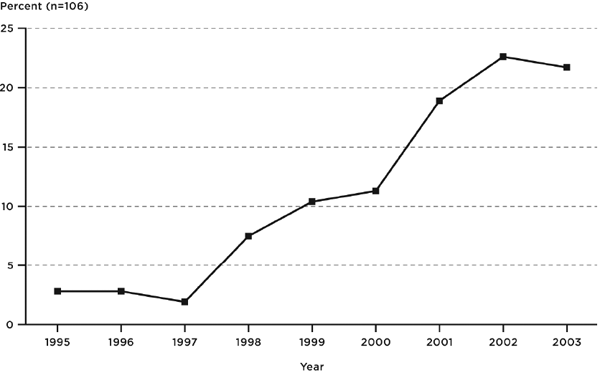

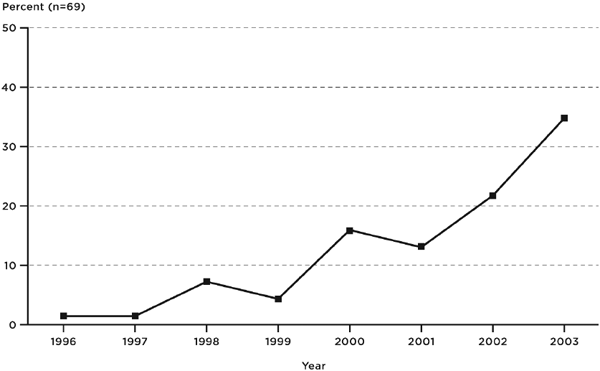

Given a minimal level of Internet capacity, how do Chinese civic associations use the Internet? Are they connected? Do they have Web sites? When did they go online or launch their Web sites? What network services do they commonly use? Our survey shows that Internet connectivity in Chinese civic associations is high for their low capacity. Out of 129 organizations, 106 (82 percent) were connected and sixty-nine (65 percent) had Web sites as of December 2003. As figure 6.2 shows, most organizations went online between 1998 and 2004, with 1998 marking the first major jump, followed by a steady annual growth. Out of 106 wired organizations, only eight went online between 1995 and 1997. A similar pattern holds for Web launching. Only two organizations had Web sites before 1997. Web launching jumped in the year 2000, with 86 percent (fifty-nine) starting their Web sites between 2000 and 2003 (see figure 6.3). Not surprisingly, Web launching lags a year or two behind the initial wiring of the organizations, indicating that organizations do not launch Web sites as soon as they go online.

FIGURE 6.2 Chinese Civic Associations Connected to Internet by Year, 1995–2003 (percent, n=106)

The timing of civic organizations going online and launching Web sites parallels the national diffusion of the Internet. Although China was connected to the Internet in 1994, the Internet did not become widely available until about 1998. There were only about ten thousand Internet users in 1994. In December 1998, the number of Internet users exceeded two million and the number of computer hosts reached over 700,000. Thereafter, the development of the Internet accelerated. During the eight-year period from 1997 to 2004, 1999 and 2000 saw the most dramatic growth in the number of computer hosts and Internet users.49

The Internet is associated with a variety of network applications. Among these, e-mail is the most frequently used by Chinese civic associations, followed by search engines and Web sites. As table 6.3 shows, electronic newsletters and BBSs are used quite often. Twenty-five percent of surveyed organizations indicate that they frequently use electronic newsletters, while 14.3 percent indicate frequent use of BBSs. This is particularly notable in view of the previously mentioned report by Surman, which suggests that few nonprofit organizations in the United States or Britain use such discussion forums.50 Eleanor Burt, the author of several studies of Internet uptake by British voluntary organizations, expressed surprise at the “relatively high figure for online discussion” shown by my survey, noting that “this is an activity that has been slow to take off in the UK voluntary sector.”51

FIGURE 6.3 Number of Chinese Civic Associations Launching Homepages, 1996–2003 (percent, n=69)

The network services used by civic associations parallel national patterns for individual Internet users. As table 6.4 shows, at the national level, individual users also favor e-mail and search engines most. Similarly, interactive functions such as BBSs and chat rooms are popular. It is clear that Internet capacity and use in the voluntary and nonprofit sector is related to the overall Internet development of a country. National Internet development is an important precondition. Furthermore, Internet use by civic associations probably reflects the national Internet culture. Thus if BBS forums are more popular with Chinese civic associations than with their counterparts in more developed countries, it is probably because there is a more vibrant BBS culture in China. Indeed, my own online ethnography indicates that there is some degree of crossfertilization between the BBS forums run by civic associations and the nationally popular ones. The crossposting of messages between these two types of forums is a common phenomenon.52

TABLE 6.3 Most Frequently Used Network Services in Civic Associations in China, December 2003 (multiple option, percent)

| 95.5 | ||||

| Search engine | 58.9 | |||

| Homepage | 47.7 | |||

| Electronic newsletter | 25.0 | |||

| BBS | 14.3 | |||

| Video conference | 2.7 | |||

TABLE 6.4 Most Frequently Used Network Services for Chinese Internet Users, December 2003 (multiple option, percent)

| 88.4 | ||||

| Search engine | 61.6 | |||

| Browsing Web sites | 47.2 | |||

| BBS, community, newsgroup | 18.8 | |||

| Free personal homepage | 5.0 | |||

| Electronic magazine | 3.9 | |||

| Video conference | 0.4 | |||

Source: CNNIC report, January 2004.

The Role of the Internet in Organizational Activities

With a relative high level of Internet connection and Web presence, do Chinese civic associations use the Internet to perform core organizational activities? Which network services are used for what activities? How important is the Internet for performing various organizational tasks?

I collected both qualitative and quantitative data on these questions. One survey question asks the respondents whether they think the Internet has any special significance ( , teshu yiyi) to their organizations and what it may be. A remarkable forty organizations provided written responses to this question. Though mostly brief, these comments uniformly affirmed the importance of the Internet to their organizations. Below are a few sample comments:

, teshu yiyi) to their organizations and what it may be. A remarkable forty organizations provided written responses to this question. Though mostly brief, these comments uniformly affirmed the importance of the Internet to their organizations. Below are a few sample comments:

“Yes, it’s an important tool for strengthening cooperation and networking.”

“Low costs, broad reach, convenient.”

“The Internet is crucial for the development of our organization. It can be used to greet and understand the outside world, shorten the distance, and broaden our horizons.”

“For disabled people, the Web is an important channel for communication and participation in social life.”

“Yes. It increased our social influence.”

“Yes. It speeds up information exchange and facilitates interactions with overseas organizations. It saves time and expenses.”

“Yes. It shortens our distance with other organizations, facilitates interactions, and increases information flow.”

The quantitative data support the message of these comments while providing a more differentiated picture of the role of the Internet in different kinds of organizational tasks. Table 6.5 shows that the Internet is most important for “organizational development” and “organizing activities.” It is also important for networking, although here there are interesting differences. The Internet is more useful for interacting with peer or international organizations than with government agencies. The implication is that the Internet is a favored means of horizontal communication. This suggests that for Chinese civic associations, the Internet may not be an effective means of communicating with or lobbying government officials but may be effective for mobilizing peer groups and international organizations.

TABLE 6.5 “Overall, what role has the Internet played in your organization?” December 2003

| Organizational development | 4.1 | |||

| Organizing activities | 3.97 | |||

| Interactions with international organizations | 3.87 | |||

| Interactions with domestic organizations | 3.86 | |||

| Interactions with government agencies | 3.53 | |||

| Member recruitment | 3.07 | |||

| Fundraising | 2.99 | |||

Note: (5=most important; 1=least important).

The same pattern holds for the use of homepages. When asked what they used their homepages for, over 90 percent of the organizations selected “organizational publicity.” Over 70 percent chose “publicizing laws, regulations, and other information” and “networking with domestic organizations,” followed by “networking with international organizations” and “networking with government agencies” (table 6.6). One notable feature is that more organizations use homepages for online discussion than for fundraising or recruitment. The Internet is least important for membership recruitment and fundraising.

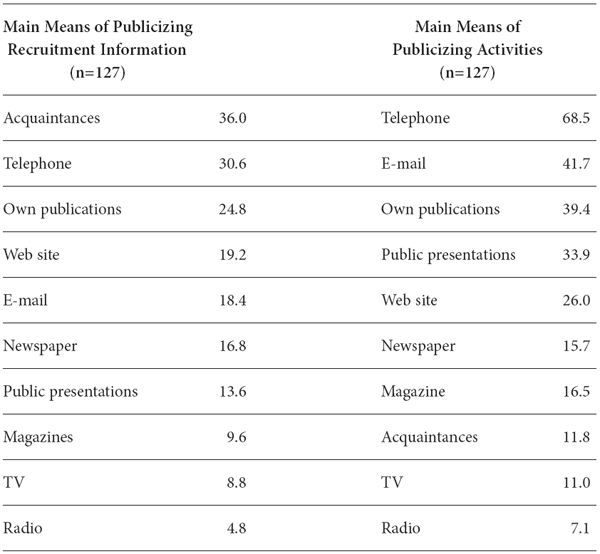

It is clear that the Internet is more useful for some purposes than others. It is a supplement to, not a replacement of, traditional means of communication. This feature is brought into further relief when organizations are asked about how they publicize activities and recruitment information. As table 6.7 shows, the favored means of publicizing recruitment information are acquaintances, the telephone, organizational publications, Web sites, and e-mail, in that order. The favored means of publicizing activities are the telephone, e-mail, organizational publications, public presentations, and Web sites.

Table 6.7 suggests that conventional mass media (newspapers, TV, and radio) appear to be least used for recruitment and publicizing activities. One obvious reason is the high costs of placing commercials in the mass media.

TABLE 6.6 Main Uses of Homepages by Chinese Civic Associations, December 2003 (percent)

| Organizational publicity | 90.9 | |||

| Publicizing laws, regulations, and other information | 75.8 | |||

| Networking (goutong) with domestic organizations | 74.2 | |||

| Networking with international organizations | 45.5 | |||

| Networking with government agencies | 33.3 | |||

| Online discussion | 24.2 | |||

| Recruiting volunteers | 10.6 | |||

| Fundraising | 6.1 | |||

Table 6.7 further shows that in publicizing recruitment information, face-to-face and telephone communication is clearly favored over Internet-based communication, yet e-mail becomes much more important in publicizing activities. This suggests that the Internet may be especially useful for publicity and information dissemination, whereas traditional means of communication may be more appropriate for activities involving interpersonal relations such as member recruitment. Of course, this is not to say that the Internet does not lend itself to interpersonal interactions. The popularity of BBS forums suggests that many such interactions take place online, but online interactions are usually anonymous and therefore differ from face-to-face or telephone interactions.

Overall, my survey shows that the Internet plays a significant role in interactions with international organizations. This finding merits special attention because of the important role, mentioned earlier, that international organizations play in the growth of new types of civic associations in China. If international organizations significantly contribute to the development of Chinese civic associations, we would expect relatively high levels of communication between them. The technological features of Internet applications facilitate long-distance communication. Do Chinese civic associations use the Internet to network with international organizations? If so, what kinds of interactions?

TABLE 6.7 Means of Publicizing Selected Types of Information in Chinese Civic Associations, December 2003 (percent)

The survey shows that ninety (or 71 percent) out of the 126 surveyed organizations report having contact with international organizations. Fifty-one organizations report having contact with fewer than five international organizations, twenty-eight report contact with six to ten international organizations, and seven report eleven to thirty. Chinese civic associations interact with international organizations for various purposes, such as information exchange, project collaboration, mutual visits, and consultation. Seventy-one out of ninety organizations (79 percent) report that information exchange is their main area of contact with international organizations. Sixty-eight percent selected “project collaboration,” 48 percent “mutual visits,” and 26 percent “consultation.” In order of descending importance, the main means of communication in networking with international organizations is e-mail, fax, telephone, and regular mail.53 This forms an interesting contrast with networking with domestic peer organizations, where the telephone is the most important means of communication, e-mail the second, fax the third, and regular mail the least.54 The importance of e-mail for international communication may be due to its speed, convenience, and low cost.

Variations in Internet Capacity and Internet Use

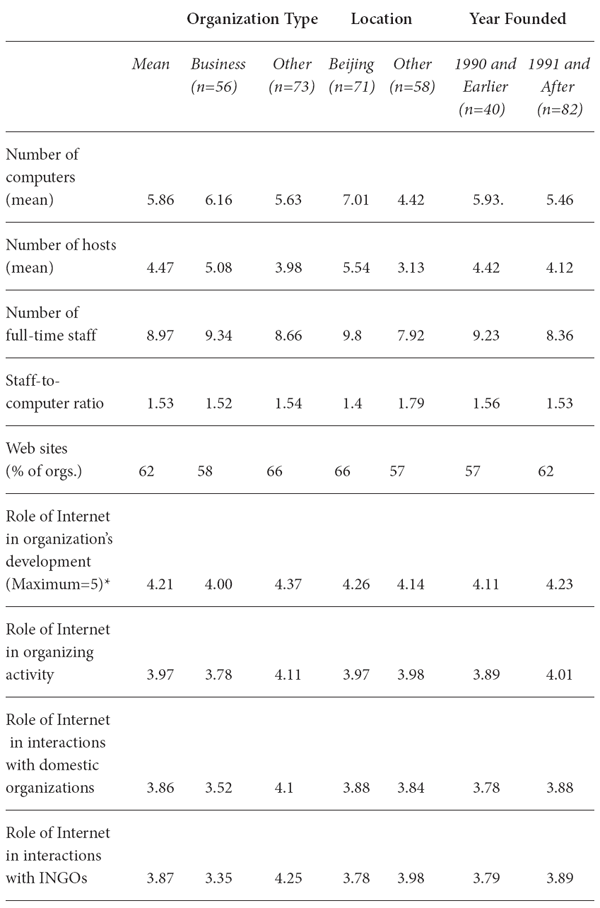

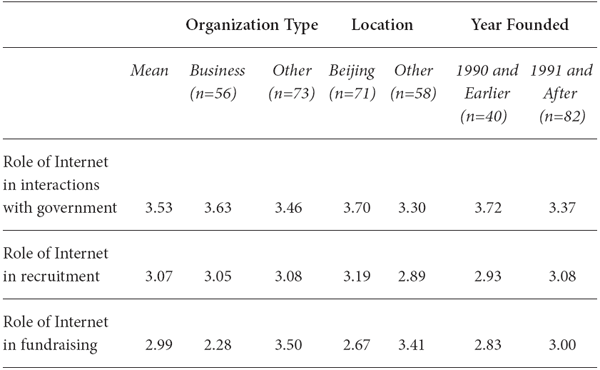

Above, I have discussed the general features of Internet capacity and use in Chinese civic associations. Variations in Internet capacity and use emerge after breaking down the sample by organizational type, location, and organizational age. Business associations make up 43 percent of the sample (fifty-six of 129). Other types include environmental organizations, women’s organizations, health organizations, social-service and community-development organizations, and culture and education organizations. Our data set contains only a small number of each of these other types. I therefore grouped the sample into two large categories by organizational type: business and nonbusiness associations. Similarly, our data set has seventy-one associations in Beijing but contains only a small number of organizations from each of the other provinces and regions in the sample. Thus I distinguished organizations by two locations, Beijing (n=71) and “Other” (n=58). I also separated organizations established in or before 1990 from those founded in or after 1991. The results are shown in table 6.8.

Table 6.8 reveals three interesting patterns. First, business associations are better equipped with the Internet than nonbusiness associations, yet they make less use of it. On average, they have more computers and computer hosts than nonbusiness associations, but only 58 percent have Web sites, compared to 66 percent of nonbusiness associations. On all but one parameter, the Internet plays a lesser role in business associations. In interactions with government agencies, the Internet appears to be slightly more important for business associations than for others. This, however, may simply reflect another phenomenon: business associations have more interactions of any kind with government agencies than do nonbusiness associations, including Internet-based interactions. This is confirmed by another finding in our survey: 75 percent of business associations indicate that they often interact with government agencies, compared to 62 percent of non-business associations.

Second, older organizations (that is, those founded in or before 1990) have better Internet capacity than younger organizations but make less use of the Internet. As in business associations, the Internet plays a lesser role in older organizations on all but one parameter. It is used more in interactions with government agencies. This again reflects the fact that older organizations simply interact with government agencies more often by any means, whether telephone or e-mail. Ninety-one percent of organizations founded in or before 1990 report that they often interact with government agencies, compared with a low 59 percent of those founded in or after 1991.55

TABLE 6.8 Internet Capacity and Use by Organizational Type, Location, and Age, December 2003

* The survey question was “Overall, what role has the Internet played in your organization?”

Third, associations in Beijing have better capacity. With an average of seven computers, they own at least two more computers than organizations not in Beijing. Overall, the Internet has a more important role in their activities than in associations elsewhere, but the differences are not very remarkable.

There are several tentative explanations for these differences. First, the organizational mission may influence an organization’s responses to the Internet. Nonbusiness organizations (such as women’s and environmental organizations) are mostly oriented to social change, whereas business associations largely represent the interests of their members. Social-change organizations need to reach a broad-based public. They must mobilize large numbers of citizens. Furthermore, many of their activities (such as environmental education) aim to disseminate information to the general public, for which the Internet is an accessible and money-saving tool. It is for these reasons that nonbusiness associations make more use of the Internet than business associations even though business associations have more Internet capacity.

This conclusion is confirmed by the finding that older organizations are better equipped than younger organizations and yet make less use of the Internet. Thus resources are not the most decisive factor in influencing Internet capacity and use. Organizations with good Internet resources do not necessarily make full use of them. Smaller and resource-poor organizations, while poorly equipped, may make much better use of whatever they have. This is a counterintuitive yet perfectly understandable finding. With a minimal Internet capacity, resource-poor grassroots organizations committed to social change have to make the most out of the Internet. For them, the Internet becomes a more central resource than for the more established and resource-rich organizations. Indeed, the Internet is no longer an ordinary resource (such as office space) but rather a resource-generating resource. Using the Internet to network with international organizations, disseminate information, or organize activities is an important way of generating organizational visibility, influence, and social capital, which may then help to generate other kinds of resources, such as project grants and personnel recruitment.

Besides organizational mission, Internet culture and organizational culture influence organizational responses to the Internet. Generally speaking, the level of Internet capacity and Internet use in civic associations should reflect the broader Internet culture. Civic associations in cities with a more developed Internet culture should be more likely to use the Internet. Thus, if the Internet plays a slightly more important role in civic associations in Beijing than in other places, it may be partly due to the more developed Internet culture and larger Internet population in Beijing. At the time of our survey in December 2003, Beijing had the largest percentage (28 percent) of its population online of all Chinese cities. Furthermore, a quarter of all .cn domain names were registered in Beijing, and one-fifth of the 595,500 Web sites in China were concentrated in Beijing.56 These factors should have a favorable impact on Internet uptake in civic associations there.

With respect to organizational culture, organizational theory would expect that the chances of organizational change decrease with an organization’s age.57 Thus, well-established organizations may experience difficulty in adopting new technology, because such technology requires new organizational capabilities.58 It has also been argued that “organizations are likely to adopt the technologies that are prominent during the time of their formation.”59 These theoretical perspectives may partially explain why older organizations in my sample use the Internet less even though they are better equipped. It may be that they have the resources to build the infrastructure but lack the innovative impulses to use new technologies. Another possible reason is that they are relatively well-established organizations and have less need for the new technology than younger organizations.

Obstacles to Better Use of the Internet

Chinese civic associations face many challenges in using the Internet. Some challenges are common to all Internet users in China, individual or organizational; others are unique to civic associations. One obstacle is political control. If commercial and public Web sites and BBS forums are regularly monitored, we cannot expect those of civic associations to be free from such surveillance. Due to the political nature of this issue, I did not ask explicit survey questions about how Chinese civic associations experience surveillance and control. Yet interview evidence does indicate the presence of surveillance. In an interview with an NGO office manager in December 2004, it was revealed to me that public-security authorities investigated the organization about Falun Gong–related messages posted in its BBS forum. The investigation involved “friendly visits” to the organization by public-security personnel. After being assured that the organization had nothing to do with the postings, the public-security people let the matter rest but did ask the organization to monitor its BBS forums more closely in the future.

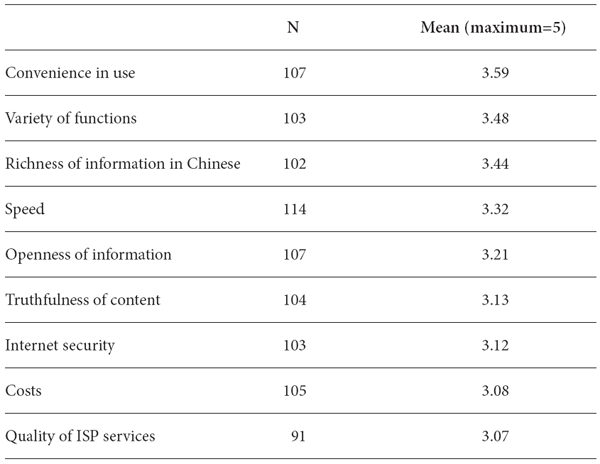

Besides political control, there are other barriers to better use of the Internet. Our survey indicates that the degree of satisfaction with various aspects of the Internet is relatively low. As table 6.9 shows, respondents report the highest level of satisfaction with “convenience in use,” but even this has an unimpressive score of 3.59 on a scale of 1–5. There are also concerns about the services of Internet service providers (ISPs), costs, Internet security, and even the truthfulness of Internet content and the openness of information. The degree of satisfaction with Internet speed scores 3.32. Considering that 43 out of 119 organizations (36 percent) still use dial-up connections and therefore must experience low satisfaction with Internet speed, this score can only be interpreted as unremarkable.

The Birth of Four Environmental Groups

The growth of environmental NGOs coincided with the development of the Internet in China. Friends of Nature was founded in 1994, the same year China was connected to the Internet. After 1998, the number of Internet users in China began to grow rapidly, jumping from 620,000 in October 1997 to over two million in December 1998. So did the number of environmental groups. In 1994, there were only nine ENGOs, four of which being college-student organizations. By 1996, the number had grown to twenty-eight, including ten student organizations. The number of ENGOs increased dramatically from 1997 to 1999. In those three years alone, at least sixty-nine ENGOs were founded, forty-three of which were student organizations. Thus by April 2001, the total number of student environmental organizations had reached 184. By 2002, nonstudent ENGOs had grown to seventy-three.60 The case of the ENGOs shows how fledgling citizen groups oriented to social change have grown through creative uses of the Internet and other new media. Four environmental groups provide exemplary cases. Greener Beijing and Green-Web were born online, while Tibetan Antelope Information Center and Han Hai Sha metamorphosed from “offline” green activist initiatives.61

TABLE 6.9 “How satisfied is your organization with the following aspects of the Internet?”

Greener Beijing originated from the Internet. It was initially a Web site designed and launched by a Mr. Song in November 1998. In the first few years, this Web site won prizes in national Web design competitions and was widely publicized in newspapers and TV news programs. Greener Beijing’s “Environmental Forum” became a popular BBS, with 2,700 registered members as of mid-2002. Members of Greener Beijing engage in three kinds of activities to promote a green culture—operating a Web site, conducting environmental-protection projects, and organizing volunteer environmental-awareness activities. Greener Beijing’s online discussion forums have been catalysts for offline environmental activism. For example, in 1999, one of the early online discussions on the recycling of used batteries sparked students at the Number One Middle School in the city of Xiamen (Fujian Province) to organize a successful community battery-recycling program. Another impressive online project was the launching of a “Save Tibetan Antelope Website Union” in January 2000, which helped draw national attention to this endangered species. The creation of the Web union helped Greener Beijing and environmentalists from twenty-seven universities in Beijing to jointly organize environmental exhibit tours on many university campuses.

Like Greener Beijing, Green-Web originated on the Internet. It was launched in December 1999. Its main founder, a Mr. Gao, previously spent two years as a volunteer Web master for the “Green Forum” of the influential portal site Netease.com. The idea of launching an independent environmental Web site first arose from discussions on the Green Forum. Green-Web was initially a virtual community with about four thousand registered users as of July 2002 (and 7,009 by February 10, 2008). The Web site functions as a space for online discussions and exchange on environmental issues, but it aims to develop into a portal site on environmental protection in China. Like Greener Beijing, Green-Web volunteers also organized community environmental activities and campaigns. One project in 2002 was a community-education initiative called “Green Summer Night.” Usually with borrowed audiovisual equipment, Green-Web volunteers put on environmental exhibits and showed environmental documentary films in the public parks in Beijing. Also in 2002, it launched an online petition campaign to oppose developing an area of wetlands and bird habitat in suburban Beijing. The local government planned to build an entertainment center and a golf course neighboring the wetlands—construction that threatened to destroy the habitat. This plan was exposed by the media in October 2001. Joining a rising campaign against the development plan, Green-Web organized an online petition from February 2 to April 12, 2002. Green-Web’s campaign collected hundreds of online signatures and sent petition letters to about ten government agencies—actions covered by the news media. According to the summary report published by Green-Web, the local government eventually canceled its development plan.

Hu Jia set up the Tibetan Antelope Information Center (TAIC) with a few fellow environmentalists in 1998. The Web site was maintained by volunteers on rented server space with grant support from several international environmental NGOs. It served as an information and communication center on the protection of the Tibetan antelope. In July 2002, the Web site contained eight sections, including Archives on Tibetan Antelope, Research, People, Data Center, News, and a link on how to help the protection efforts. The news section carried reports about what was happening in the “battlefield”—that is, on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, where environmentalists and local communities were teaming up to fight illegal poaching activities. TAIC members maintained close contact with antipoaching patrols on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and assisted local environmental protection efforts through fund-raising and serving as information liaisons between local groups and environmental NGOs in Beijing and outside China.

Han Hai Sha (literally, “Boundless Ocean of Sand”) is a volunteer network devoted to desertification problems. A Mr. Yang started planning this network with several other young environmentalists in Beijing in 2001. In March 2002, the first group of fifty volunteers was recruited through e-mail and announcements posted in the Friends of Nature and Green-Web online forums. These volunteers met twice over four months and launched the Han Hai Sha Web site and an electronic newsletter in June 2002. Han Hai Sha promotes public awareness of desertification and mobilizes community efforts to solve practical problems. It emphasizes the gathering and dissemination of information through the Internet and works closely with experts and volunteers in areas plagued or threatened by desertification. It partners with the Institute of Desert Green Engineering of the city of Chifeng—a local ENGO in Inner Mongolia—to enhance public awareness of the challenges of desertification and related problems of rural poverty. When I interviewed its main organizer in July 2002, Han Hai Sha did not own a computer and was completely reliant on volunteers.

Evolution, Change, and Challenges

More than five years have passed since I first studied these four groups in 2002. A major change is the demise of TAIC, with Hu Jia’s departure. Hu continued to be involved with environmental activism, but his focus shifted to HIV/AIDS issues. As I will discuss in the next chapter, he would eventually become one of China’s most prominent human-rights activists. TAIC’s decease therefore is not necessarily a sign of failure. Its main leader did not leave it to give up activism but rather became involved in more contentious areas of activism. However, the other three groups all have grown and have all done so with sustained and creative use of the Internet. Greener Beijing changed its English name to Greener Beijing Institute, redesigned and expanded its Web site, and continues to maintain active online forums and organize offline activities and campaigns.62 In 2005, when I met with its main organizer again, Han Hai Sha had found a new direction. Its members had just begun to promote the new notion of “environmental protection from the soul” (xinling huanbao). The basic idea is that environmental change must begin with self-transformation, and self-transformation must start in everyday life.63 Consequently, its projects began to focus more on humanistic education, grassroots-community construction, and the promotion of organic agriculture. Its members travel frequently to rural areas. In the cities, they organize public film screenings and have built a remarkable collection of over one thousand DVDs. On their Web sites, discussions in their BBS forums remain active. Han Hai Sha’s electronic newsletters have expanded in content and are mailed to subscribers and downloadable from its Web site.

The development of Green-Web illustrates particularly well the evolution of a grassroots organization in their use of the Internet. Green-Web continues to organize projects and campaigns. More than twenty projects or campaigns were listed in Green-Web’s online forum as of February 16, 2008.64 In 2004, Green-Web initiated a successful campaign to protect the Beijing Zoo. In April that year, Green-Web volunteers learned of a plan to move the Beijing Zoo from its current location. The volunteers publicized the information in its own BBS forum and in other online forums, leading to heated public debates about this issue. Volunteers also used e-mail and the telephone to mobilize the mass media. Eventually the Ministry of Construction revised its regulations about the management of urban zoos. The regulations contained a new article requiring public hearings for urban zoo-design proposals. This article in effect means that any plan to move the Beijing Zoo will have to go through public-hearing procedures.65

In 2003, Green-Web initiated efforts to improve its organizational development. It held its first membership meeting in August and elected a small coordinating team to function as a leadership organ. A second membership meeting was held in 2007, at which a new coordinating team was elected. Since its first meeting, the new team has published its minutes in Green-Web’s blog. The minutes provide evidence of Green-Web struggling with organizational development. A main item on the agenda of its first meeting on April 2, 2007, for example, was a brainstorming session about visions for Green-Web. One group member proposed that each person write down a list of keywords he or she would use to describe Green-Web. The following list came up: “volunteer spirit,” “loneliness,” “communication,” “people,” “action,” “growth,” “identity,” “respect,” “sustainable development,” “happiness,” “diversity,” “recognition,” “persevere,” “get rid of,” “environment-friendly lifestyle,” “change,” “support.” Based on this list, one participant composed the following sentence: “Respect diversity, get rid of loneliness, persevere in action for sustainable development.” Another came up with: “Grow in the middle of respect and tolerance, develop in the middle of change and action.”66 The minutes of its fifth meeting, which took place on May 16, 2007, contained a resolution about the procedures of initiating changes to Green-Web’s Web site. It reported that Green-Web’s BBS forum was not only its members’ forum but also belonged to all its Internet users. Therefore, Green-Web’s leadership group did not have the authority to change the Web site. The meeting resolved that a message would be posted in the forum to solicit all forum members’ views and then ask forum members to vote on whether and how to revise the Web site for the forum.67

Green-Web’s minutes also reveal how its members negotiate information management. One item at the fifth meeting was about whether to publish a gay and lesbian summer-camp announcement on its Web site. The minutes recorded that the discussions about this issue were extremely heated and at one point almost out of control. The discussions reached a resolution with four “yea” votes and three “nay” votes. The group resolved to publish the announcement with appropriate disclaimers. It further resolved that future complaints by forum users be handled in a similar fashion: the complaints should be immediately transmitted to all members of the coordinating team through group mail and all resolutions reached through voting.

Conclusion

This chapter provides the first empirical analysis of the level of Internet capacity and Internet use in civic associations in China. The analysis leads to five conclusions. First, my survey shows that Chinese civic associations have a minimal level of Internet capacity. More than 80 percent of these organizations were connected to the Internet and more than half had Web sites. Only two out of 129 organizations did not own a computer at the time of the survey. All the others had at least one computer. Considering that small and poorly equipped organizations actually make better use of the Internet, the difference between zero and one computer has to be a qualitative difference, for with even one computer, an organization can be linked to the outside world.

Second, my analysis shows that social-change organizations, younger organizations, and organizations in Beijing make more use of the Internet than business associations, older organizations, and organizations outside Beijing. This is so even when they have lower capacity. This finding suggests that organizational mission, organizational culture, and Internet culture influence organizational responses to the Internet. Social-change organizations aim to reach a broad-based public, organizations founded in or after 1991 have developed in tandem with the Internet and are thus acculturated to it, and organizations in Beijing exist in a culture of high Internet density. To promote Internet use by civic associations, therefore, it is necessary to build the national Internet culture and an organizational culture committed to horizontal relationships and the open flow of information. In the broadest sense, it may be suggested that the civic uses of the Internet depend on a democratic social and political environment, just as they help to cultivate such an environment.

Third, organizations with bare-bones Internet capacity can make effective use of whatever they have, whereas resource-rich and better-equipped organizations may not. The Internet may be more valuable to those shoestring organizations.68 It has been observed that in the history of the Internet worldwide, civil-society organizations embraced the Internet before government and commercial institutions.69 This was not because civil-society organizations had more resources but rather because they needed the Internet more and therefore they would use what they had to full capacity.70 This explains why Chinese civic associations make active use of the Internet despite their low capacity. It is essential for civic organizations to have a minimal level of Internet capacity, but capacity does not determine use. For civil-society organizations to achieve strategic growth by taking full advantage of new technological capabilities, it is equally important to understand what needs the new technologies can best meet.

Fourth, my survey shows that the Internet is most useful for publicity, information dissemination, and networking with peer and international organizations. In interactions with government agencies or when it comes to recruitment or fundraising, Chinese civic associations rely more on face-to-face and telephone communication. This finding shows that corresponding to the hierarchical power structures in society is a hierarchy of communication media. In this hierarchical structure, different kinds of organizational tasks are accomplished with different communication media. Thus for Chinese civic associations, the Internet works well for information dissemination and networking with peers and international counterparts but less well for interactions with government agencies.

Finally, four case studies of Web-based environmental groups illustrate the ways in which grassroots organizations achieve organizational growth through their use of the Internet. Two of the four groups were born out of online interactions; the other two were organized offline but then went online. All four groups rely significantly on their Web sites for building organizational identity, mobilizing resources, and organizing activities. All four groups have engaged in online environmental activism. Thus organizations provide a basis for launching online activism, and online activism is a means of organizational building. These four cases illustrate the dynamics of mutual constitution of the Internet and civil society.

All these findings suggest that the interactions between civic associations and the Internet have produced a “web” of civic associations in China and that this “web” is civilly engaged. This web of associations assumes special significance in China’s political context. Chinese civic associations must negotiate a state that seeks to maintain political control over civic associations. Perhaps it is precisely because they have to manage this daunting environment that Chinese civic associations have built at least a minimal level of Internet capacity. Such capacity is important for organizational survival. Herein lies an important message concerning the relationship between technological change and institutional transformation. When the developments of new institutional forms (such as Chinese civic associations) and new technologies (such as the Internet) coincide, their interactions become more than incidental. The new technologies may become a strategic opportunity and resource for achieving organizational and social change even where there is strong resistance to change. Such a strategic opportunity and resource does not always present itself. When it does, it is not always seized. This chapter shows how grassroots civic associations in urban China have seized the opportunity in achieving organizational development and social change.