USING YOUR OWN MOBILE DEVICE IN EUROPE

USING A EUROPEAN SIM CARD IN A MOBILE PHONE

USING LANDLINES AND COMPUTERS IN EUROPE

This chapter covers the practical skills of European travel: how to get tourist information, pay for things, sightsee efficiently, find good-value accommodations, eat affordably but well, use technology wisely, and get between destinations smoothly. To study ahead and round out your knowledge, check out “Resources.”

The website of the French national tourist office, us.rendezvousenfrance.com, is a wealth of information, with particularly good resources for special-interest travel, and plenty of free-to-download brochures. Paris’ official TI website, www.parisinfo.com, offers practical information on hotels, special events, museums, children’s activities, fashion, nightlife, and more. (For other useful websites, see here.)

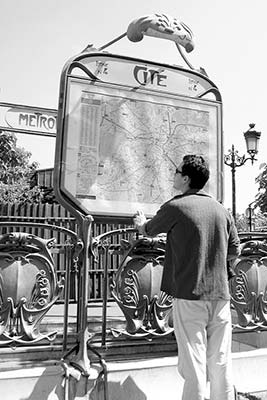

In Paris, TI offices are few and far between. They aren’t helpful enough to warrant a special trip, but if you’re near one anyway, consider stopping by to confirm opening times, pick up a city map, and get information on public transit (including bus and train schedules), walking tours, special events, and nightlife. For TI locations, see here (the most handy locations may be at the airports).

Emergency and Medical Help: In France, dial 112 for any emergency. For English-speaking police, call 17. To summon an ambulance, call 15. If you get sick, do as the locals do and go to a pharmacist for advice. Or ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services.

Theft or Loss: To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy or consulate (see here). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them (see “Damage Control for Lost Cards” on here). File a police report, either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for lost or stolen rail passes or travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport or credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help. To minimize the effects of loss, back up your digital photos and other files frequently.

Time Zones: France, like most of continental Europe, is generally six/nine hours ahead of the East/West Coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Europe “springs forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after most of North America), and “falls back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). For a handy online time converter, see www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

Business Hours: In Paris, most shops are open Monday through Saturday (10:00-12:00 & 14:00-19:00) and closed Sunday (except in the Marais neighborhood and along the Champs-Elysées). Many small markets, boulangeries (bakeries), and street markets are open Sunday mornings until noon.

Saturdays are virtually weekdays, with earlier closing hours at some shops. Banks are generally open on Saturday and closed on Sunday and possibly Monday. Sundays have the same pros and cons as they do for travelers in the US: Special events and weekly markets pop up (usually until about noon) and sightseeing attractions are generally open, while many shops are closed, public transportation options are fewer, and there’s no rush hour. Friday and Saturday evenings are rowdy; Sunday evenings are quiet.

Watt’s Up? Europe’s electrical system is 220 volts, instead of North America’s 110 volts. Most newer electronics (such as laptops, battery chargers, and hair dryers) convert automatically, so you won’t need a converter, but you will need an adapter plug with two round prongs, sold inexpensively at travel stores in the US. Avoid bringing older appliances that don’t automatically convert voltage; instead, buy a cheap replacement in Europe. You can buy low-cost hair dryers and other small appliances at Darty and Monoprix stores, which you’ll find in most Parisian neighborhoods (ask your hotelier for the closest branch).

Discounts: Discounts aren’t always listed in this book. However, many sights offer discounts for youths (usually up to age 18), students (with proper identification cards, www.isic.org), families, and groups of 10 or more. Always ask, and have your passport available at sights for proof. Seniors (age 60 and over) may get the odd discount, though these are often limited to citizens of the European Union (EU). To inquire about a senior discount, ask, “Réduction troisième âge?” (ray-dewk-see-ohn trwah-zee-ehm ahzh).

Online Translation Tips: You can use Google’s Chrome browser (available free at www.google.com/chrome) to instantly translate websites. With one click, the page appears in (very rough) English translation. You can also paste the URL of the site into the translation window at www.google.com/translate. The Google Translate app converts spoken English into most European languages (and vice versa) and can also translate text it “reads” with your mobile device’s camera.

This section offers advice on how to pay for purchases on your trip (including getting cash from ATMs and paying with plastic), dealing with lost or stolen cards, VAT (sales tax) refunds, and tipping.

Bring both a credit card and a debit card. You’ll use the debit card at cash machines (ATMs) to withdraw local cash for most purchases, and the credit card to pay for larger items. Some travelers carry a third card, in case one gets demagnetized or eaten by a temperamental machine. For an emergency reserve, consider bringing €200 in hard cash in €20-50 bills (bring euros, as dollars can be hard to change in France).

Cash is just as desirable in Europe as it is at home. Small businesses (B&Bs, mom-and-pop cafés, shops, etc.) prefer that you pay your bills with cash. Some vendors will charge you extra for using a credit card, some won’t accept foreign credit cards, and some won’t take any credit cards at all. Cash is the best—and sometimes only—way to pay for cheap food, bus fare, taxis, and local guides.

Throughout Europe, ATMs are the standard way for travelers to get cash. They work just like they do at home. To withdraw money from an ATM (known as a distributeur; dee-stree-bew-tur), you’ll need a debit card (ideally with a Visa or MasterCard logo for maximum usability), plus a PIN code (numeric and four digits). For increased security, shield the keypad when entering your PIN code, and don’t use an ATM if anything on the front of the machine looks loose or damaged (a sign that someone may have attached a “skimming” device to capture account information). Try to withdraw large sums of money to reduce the number of per-transaction bank fees you’ll pay.

When possible, use ATMs located outside banks—a thief is less likely to target a cash machine near surveillance cameras, and if your card is munched by a machine, you can go inside for help. Stay away from “independent” ATMs such as Travelex, Euronet, YourCash, Cardpoint, and Cashzone, which charge huge commissions, have terrible exchange rates, and may try to trick users with “dynamic currency conversion” (described at the end of “Credit and Debit Cards,” next). Although you can use a credit card to withdraw cash at an ATM, this comes with high bank fees and only makes sense in an emergency.

While traveling, if you want to monitor your accounts online to detect any unauthorized transactions, be sure to use a secure connection (see here).

Pickpockets target tourists, particularly those arriving in Paris—dazed and tired—carrying luggage in the Métro and RER trains and stations. To safeguard your cash, wear a money belt—a pouch with a strap that you buckle around your waist like a belt and tuck under your clothes. Keep your cash, credit cards, and passport secure in your money belt, and carry only a day’s spending money in your front pocket.

For purchases, Visa and MasterCard are more commonly accepted than American Express. Just like at home, credit or debit cards work easily at larger hotels, restaurants, and shops. I typically use my debit card to withdraw cash to pay for most purchases. I use my credit card sparingly: to book hotel reservations, to buy advance tickets for events or sights, to cover major expenses (such as car rentals or plane tickets), and to pay for things online or near the end of my trip (to avoid another visit to the ATM). While you could instead use a debit card for these purchases, a credit card offers a greater degree of fraud protection.

Ask Your Credit- or Debit-Card Company: Before your trip, contact the company that issued your debit or credit cards.

• Confirm that your card will work overseas, and alert them that you’ll be using it in Europe; otherwise, they may deny transactions if they perceive unusual spending patterns.

• Ask for the specifics on transaction fees. When you use your credit or debit card—either for purchases or ATM withdrawals—you’ll typically be charged additional “international transaction” fees of up to 3 percent (1 percent is normal) plus $5 per transaction. Some banks have agreements with European partners that help save on fees (for example, Bank of America customers don’t have to pay the transaction fee when using French Paribas-BNP ATMs). If your card’s fees seem high, consider getting a different card just for your trip: Capital One (www.capitalone.com) and most credit unions have low-to-no international fees.

• Verify your daily ATM withdrawal limit, and if necessary, ask your bank to adjust it. I prefer a high limit that allows me to take out more cash at each ATM stop and save on bank fees; some travelers prefer to set a lower limit in case their card is stolen. Note that foreign banks also set maximum withdrawal amounts for their ATMs.

• Get your bank’s emergency phone number in the US (but not its 800 number, which isn’t accessible from overseas) to call collect if you have a problem.

• Ask for your credit card’s PIN in case you need to make an emergency cash withdrawal or you encounter Europe’s chip-and-PIN system; the bank won’t tell you your PIN over the phone, so allow time for it to be mailed to you.

Magnetic-Stripe versus Chip-and-PIN Credit Cards: Europeans are increasingly using chip-and-PIN credit cards embedded with an electronic security chip and requiring a four-digit PIN. Your American-style card (with just the old-fashioned magnetic stripe) will work fine in most places. But there could be minor inconveniences; it might not work at unattended payment machines, such as those at train and subway stations, toll plazas, parking garages, bike-rental kiosks, and gas pumps. If you have problems, try entering your card’s PIN, look for a machine that takes cash, or find a clerk who can process the transaction manually.

Major US banks are beginning to offer credit cards with chips. Many of these are not true chip-and-PIN cards, but instead are “chip-and-signature” cards, for which your signature verifies your identity. These cards should work for live transactions and at most payment machines, but won’t work for offline transactions such as at unattended gas pumps. If you’re concerned, ask if your bank offers a true chip-and-PIN card. Andrews Federal Credit Union (www.andrewsfcu.org) and the State Department Federal Credit Union (www.sdfcu.org) offer these cards and are open to all US residents.

No matter what kind of card you have, it pays to carry euros; remember, you can always use an ATM to withdraw cash with your magnetic-stripe debit card.

Dynamic Currency Conversion: If merchants or hoteliers offer to convert your purchase price into dollars (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC), refuse this “service.” You’ll pay even more in fees for the expensive convenience of seeing your charge in dollars. If your receipt shows the total in dollars only, ask for the transaction to be processed in the local currency. If the clerk refuses, pay in cash—or mark the receipt “local currency not offered” and dispute the DCC charges with your bank.

Some ATMs and retailers try to confuse customers by presenting DCC in misleading terms. If an ATM offers to “lock in” or “guarantee” your conversion rate, choose “proceed without conversion.” Other prompts might state, “You can be charged in dollars: Press YES for dollars, NO for euros.” Always choose the local currency in these situations.

If you lose your credit, debit, or ATM card, you can stop people from using your card by reporting the loss immediately to the respective global customer-assistance centers. Call these 24-hour US numbers collect: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111). In France, to make a collect call to the US, dial 08 00 90 06 24, then say “operator” for an English-speaking operator. European toll-free numbers (listed by country) can be found at the websites for Visa and MasterCard. For another option (with the same results), you can call these toll-free numbers in France: Visa (tel. 08 00 90 11 79) and MasterCard (tel. 08 00 90 13 87). American Express has a Paris office, but the call isn’t free (tel. 01 47 77 70 00, greeting is in French, dial 1 to speak with someone in English).

Try to have this information ready: full card number, whether you are the primary or secondary cardholder, the cardholder’s name exactly as printed on the card, billing address, home phone number, circumstances of the loss or theft, and identification verification (your birth date, your mother’s maiden name, or your Social Security number—memorize this, don’t carry a copy). If you are the secondary cardholder, you’ll also need to provide the primary cardholder’s identification-verification details. You can generally receive a temporary card within two or three business days in Europe (see www.ricksteves.com/help for more).

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for any unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50.

Tipping (donner un pourboire) in France isn’t as automatic and generous as it is in the US. For special service, tips are appreciated, but not expected. As in the US, the proper amount depends on your resources, tipping philosophy, and the circumstances, but some general guidelines apply.

Restaurants: At cafés and restaurants, a service charge is included in the price of what you order, and it’s unnecessary to tip extra, though you can for superb service. For details on tipping in restaurants, see here.

Taxis: For a typical ride, round up your fare a bit (for instance, if the fare is €13, pay €14). If the cabbie hauls your bags and zips you to the airport to help you catch your flight, you might want to toss in a little more. But if you feel like you’re being driven in circles or otherwise ripped off, skip the tip.

Services: In general, if someone in the service industry does a super job for you, a small tip of a euro or two is appropriate...but not required. If you’re not sure whether (or how much) to tip for a service, ask a local for advice.

Wrapped into the purchase price of your French souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT) of about 20 percent. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase more than €175 (about $195) worth of goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. Typically, you must ring up the minimum at a single retailer—you can’t add up your purchases from various shops to reach the required amount.

Getting your refund is straightforward and, if you buy a substantial amount of souvenirs, well worth the hassle. If you’re lucky, the merchant will subtract the tax when you make your purchase. (This is more likely to occur if the store ships the goods to your home.) Otherwise, you’ll need to:

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document, called a bordereau de détaxe. You’ll have to present your passport. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. Process your VAT document at your last stop in the European Union (such as at the airport) with the customs agent who deals with VAT refunds. Arrive an additional hour before you need to check in for your flight to allow time to find the local customs office—and to stand in line. It’s best to keep your purchases in your carry-on. If they’re too large or dangerous to carry on (such as knives), pack them in your checked bags and alert the check-in agent. You’ll be sent (with your tagged bag) to a customs desk outside security; someone will examine your bag, stamp your paperwork, and put your bag on the belt. You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your chic new shoes, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. You’ll need to return your stamped document to the retailer or its representative. Many merchants work with a service, such as Global Blue or Premier Tax Free, that has offices at major airports, ports, or border crossings (either before or after security, probably strategically located near a duty-free shop). At Charles de Gaulle, you’ll find them at the check-in area (or ask for help at an orange ADP info desk). These services, which extract a 4 percent fee, can refund your money immediately in cash or credit your card (within two billing cycles). If the retailer handles VAT refunds directly, it’s up to you to contact the merchant for your refund. You can mail the documents from home, or more quickly, from your point of departure (using an envelope you’ve prepared in advance or one that’s been provided by the merchant). You’ll then have to wait—it can take months.

You are allowed to take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 31 days. You can take home many processed and packaged foods: vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. Fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed, with exceptions for some canned items. As for alcohol, you can bring in one liter duty-free (it can be packed securely in your checked luggage, along with any other liquid-containing items).

To bring alcohol (or liquid-packed foods) in your carry-on bag on your flight home, buy it at a duty-free shop at the airport. You’ll increase your odds of getting it onto a connecting flight if it’s packaged in a “STEB”—a secure, tamper-evident bag. But stay away from liquids in opaque, ceramic, or metallic containers, which usually cannot be successfully screened (STEB or no STEB).

For details on allowable goods, customs rules, and duty rates, visit help.cbp.gov.

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Paris’ finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your must-see sights. For a one-stop look at opening hours, see “Paris at a Glance” (here). Remember, the Louvre and some other museums are closed on Tuesday, and many others are closed on Monday (see “Daily Reminder” on here). Most sights keep stable hours, but you can easily confirm the latest by checking their websites or picking up the booklet Musées, Monuments Historiques, et Expositions (free at most museums). You can also find good information on many of Paris’ sights online at www.parisinfo.com.

Don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know when a place will close unexpectedly for a holiday, strike, or restoration. Many museums are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Labor Day (May 1). A list of holidays is on here; check online for possible museum closures during your trip. In summer, some sights may stay open late. Off-season, many museums have shorter hours.

Going at the right time helps avoid crowds. This book offers tips on the best times to see specific sights. Try visiting popular sights very early (arrive at least 15 minutes before opening time) or very late. Evening visits are usually peaceful, with fewer crowds. For example, the Louvre and Orsay museums are open selected evenings, while the Pompidou Center is open late every night except Tuesday (when it’s closed all day). For a list of sights that are open in the evenings, see “Paris for Early Birds and Night Owls” (here).

Consider buying a Paris Museum Pass, which can speed you through lines and save you money, or booking advance tickets for popular sights (for details, see here). For more money-saving tips, see “Affording Paris’ Sights” on here.

Study up. To get the most out of the self-guided tours and sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit. The Louvre is more interesting if you understand why the Venus de Milo is so disarming.

Here’s what you can typically expect:

Entering: Be warned that you may not be allowed to enter if you arrive 30 to 60 minutes before closing time. And guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last.

Some important sights have a security check, where you must open your bag or send it through a metal detector. Some sights require you to check daypacks and coats. (If you’d rather not check your daypack, try carrying it tucked under your arm like a purse as you enter.) If you check a bag, the attendant may ask you if it contains anything of value—such as a camera, phone, money, passport—since these usually cannot be checked.

At churches—which often offer interesting art (usually free) and a cool, welcome seat—a modest dress code (no bare shoulders or shorts) is encouraged though rarely enforced.

Photography: If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask a guard. Generally, taking photos without a flash or tripod is allowed. Some sights ban photos altogether.

Temporary Exhibits: Museums may show special exhibits in addition to their permanent collection. Some exhibits are included in the entry price, while others come at an extra cost (which you may have to pay even if you don’t want to see the exhibit).

Expect Changes: Artwork can be on tour, on loan, out sick, or shifted at the whim of the curator. Pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask museum staff if you can’t find a particular item. Say the title or artist’s name, or point to the photograph in this book and ask for its location by saying, “Où est?” (oo ay).

Audioguides and Apps: Many sights rent audioguides, which generally offer worthwhile recorded descriptions in English. If you bring your own earbuds, you can enjoy better sound and avoid holding the device to your ear. To save money, bring a Y-jack and share one audioguide with your travel partner. Increasingly, museums and sights offer apps—often free—that you can download to your mobile device (check their websites). I’ve produced free, downloadable audio tours for my Historic Paris Walk, the Louvre, Orsay Museum, and Versailles; these are indicated in this book with the symbol  . For more on my audio tours, see here.

. For more on my audio tours, see here.

Services: Important sights may have an on-site café or cafeteria (usually a handy place to rejuvenate during a long visit). The WCs at sights are free and generally clean.

Before Leaving: At the gift shop, scan the postcard rack or thumb through a guidebook to be sure that you haven’t overlooked something that you’d like to see.

Every sight or museum offers more than what is covered in this book. Use the information in this book as an introduction—not the final word.

Accommodations in Paris generally are easy to find and usually cost less than comparable places in other big European cities. Choose from one- to five-star hotels (two and three stars are my mainstays), bed-and-breakfasts (chambres d’hôtes, usually cheaper than hotels), hostels, and apartments.

A major feature of the Sleeping sections of this book is my extensive and opinionated listing of good-value rooms. I like places that are clean, central, relatively quiet at night, reasonably priced, friendly, small enough to have a hands-on owner and stable staff, and run with a respect for French traditions. (In Paris, for me, five out of these seven criteria means it’s a keeper.) I’m more impressed by a convenient location and a fun-loving philosophy than flat-screen TVs and a pricey laundry service.

Book your accommodations well in advance, especially if you want to stay at one of my top listings or if you’ll be traveling during busy times. Reserving ahead is particularly important for Paris—the sooner, the better. Wherever you’re staying, be ready for crowds during these holiday periods: Easter weekend; Labor Day; Ascension weekend; Pentecost weekend; Bastille Day and the week during which it falls; and the winter holidays (mid-Dec-early Jan). In August and at other times when business is slower, some Paris hotels offer lower rates to fill their rooms. Check hotel websites for the best deals.

See here for a list of major holidays and festivals in France; for tips on making reservations, see here.

I’ve described my recommended accommodations using a Sleep Code (see sidebar). The prices I list are for one-night stays in peak season, do not include breakfast (unless noted), and assume you’re booking directly with the hotel, not through an online hotel-booking engine or TI. Booking services extract a commission from the hotel, which logically closes the door on special deals. Book direct.

If I give a single rate for a room, it applies to high season (figure Easter to October); if I give a range, the lower rates are likely available only in winter. Hotels in France must charge a daily tax (taxe du séjour) of about €1-2 per person per day. Some hotels include it in the listed prices, but most add it to your bill.

My recommended hotels each have a website (often with a built-in booking form) and an email address; you can expect a response in English within a day (and often sooner). You’ll almost always find the lowest rates through a hotel’s own website.

If you’re on a budget, it’s smart to email several hotels to ask for their best price. Comparison-shop and make your choice. This is especially helpful when dealing with the larger hotels that use “dynamic pricing,” a computer-generated system that predicts the demand for particular days and sets prices accordingly: High-demand days can be more than double the price of low-demand days. This makes it impossible for a guidebook to list anything more accurate than a wide range of prices. I regret this trend. While you can assume that hotels listed in this book are good, it’s difficult to say which ones are the better value unless you email to confirm the price.

As you look over the listings, you’ll notice that some accommodations promise special prices to Rick Steves readers. To get these rates, you must book direct (that is, not through a booking site like TripAdvisor or Booking.com), mention this book when you reserve, and then show the book upon arrival. Rick Steves discounts apply to readers with ebooks as well as printed books. Because I trust hotels to honor this, please let me know if you don’t receive a listed discount. Note, though, that discounts understandably may not be applied to promotional rates.

In general, prices can soften if you stay at least three nights or mention this book. You can also try asking for a cheaper room or a discount, or offer to skip breakfast.

In this book, the price for a double room will normally range from €60 (very simple; toilet and shower down the hall) to €500 (grand lobbies, maximum plumbing, and the works), with most clustering around €120-180 (with private bathrooms).

The French have a simple hotel rating system based on amenities and rated by stars (indicated in this book by asterisks, from * through *****). One star is modest, two has most of the comforts, and three is generally a two-star with a fancier lobby and more elaborately designed rooms. Four-star places give marginally more comfort than those with three. Five stars probably offer more luxury than you’ll have time to appreciate. Two- and three-star hotels are required to have an English-speaking staff, though nearly all hotels I recommend have someone who speaks English.

The number of stars does not always reflect room size or guarantee quality. One- and two-star hotels are less expensive, but some three-star (and even a few four-star hotels) offer good value, justifying the extra cost. Unclassified hotels (no stars) can be bargains or depressing dumps.

Prices vary within each hotel depending on room size and whether the room has a bathtub or shower and twin beds or a double bed (tubs and twins cost more than showers and double beds). If you have a preference, ask for it. Hotels often have more rooms with tubs (which the French prefer) and are inclined to give you one by default. You can save as much as €25 per night by finding the increasingly rare room without a private shower or toilet.

Most French hotels now have queen-size beds—to confirm, ask, “Avez-vous des lits de cent-soixante?” (ah-vay-voo day lee duh sahn-swah-sahnt). Some hotels push two twins together under king-size-sheets and blankets to make le king size. If you’ll take either twins or a double, ask for a generic une chambre pour deux (room for two) to avoid being needlessly turned away. Many hotels have a few family-friendly rooms that open up to each other (chambres communiquantes).

Extra pillows and blankets are often in the closet or available on request. To get a pillow, ask for “Un oreiller, s’il vous plaît” (uhn oh-ray-yay, see voo play).

Old, characteristic, budget Parisian hotels have always been cramped. Retrofitted with private bathrooms and elevators (as most are today), they are even more cramped. Hotel elevators are often very small—pack light, or you may need to take your bags up one at a time.

Hotel lobbies, halls, and breakfast rooms are off-limits to smokers, though they can light up in their rooms. Still, I seldom smell any smoke in my rooms. Some hotels have nonsmoking rooms or floors—ask.

Most hotels offer some kind of breakfast (see here), but it’s rarely included in the room rates—pay attention when comparing rates between hotels. The price of breakfast correlates with the price of the room: The more expensive the room, the more expensive the breakfast. This per-person charge rises with the number of stars the hotel has and can add up, particularly for families. While hotels hope you’ll buy their breakfast, it’s optional unless otherwise noted; to save money, head to a bakery or café instead.

Hoteliers uniformly detest it when people bring food into bedrooms. Dinner picnics are particularly frowned upon: Hoteliers worry about cleanliness, smells, and attracting insects. Be tidy and considerate.

If you’re arriving in the morning, your room probably won’t be ready. Drop your bag safely at the hotel and dive right into sightseeing.

Hoteliers can be a great help and source of advice. Most know their city well, and can assist you with everything from public transit and airport connections to calling an English-speaking doctor, or finding a good restaurant, Wi-Fi hotspot (point Wi-Fi, pwan wee-fee), or self-service launderette (laverie automatique, lah-vay-ree oh-to-mah-teek).

Even at the best places, mechanical breakdowns occur: Air-conditioning malfunctions, sinks leak, hot water turns cold, and toilets gurgle and smell. Report your concerns clearly and calmly at the front desk. For more complicated problems, don’t expect instant results.

To guard against theft in your room, keep valuables out of sight. Some rooms come with a safe, and other hotels have safes at the front desk. I’ve never bothered using one.

Checkout can pose problems if surprise charges pop up on your bill. If you settle your bill the afternoon before you leave, you’ll have time to discuss and address any points of contention (before 19:00, when the night shift usually arrives).

Above all, keep a positive attitude. Remember, you’re on vacation. If your hotel is a disappointment, spend more time out enjoying the city you came to see.

A hostel (auberge de jeunesse) provides cheap beds where you sleep alongside strangers for about €23-35 per night. Travelers of any age are welcome if they don’t mind dorm-style accommodations and meeting other travelers. Most hostels offer kitchen facilities, guest computers, Wi-Fi, and a self-service laundry. Nowadays, concerned about bedbugs, hostels are likely to provide all bedding, including sheets. Family and private rooms may be available on request.

Independent hostels tend to be easygoing, colorful, and informal (no membership required); www.hostelworld.com is the standard way backpackers search and book hostels, but also try www.hostelz.com and www.hostels.com.

Official hostels are part of Hostelling International (HI) and share an online booking site (www.hihostels.com). HI hostels typically require that you either have a membership card or pay extra per night.

Hip Hop Hostels is a clearinghouse for budget hotels and hostels. It’s worth a look for its good selection of cheap accommodations throughout Paris (tel. 01 48 78 10 00, www.hiphophostels.com).

Renting an apartment or house can be a fun and cost-effective way to go local. Websites such as Booking.com, Airbnb, VRBO, and FlipKey let you browse properties and correspond directly with European property owners or managers. Airbnb and Roomorama also list rooms in private homes. Beds range from air-mattress-in-living-room basic to plush-B&B-suite posh. If you want a place to sleep that’s free, Couchsurfing.org is a vagabond’s alternative to Airbnb. It lists millions of outgoing members, who host fellow “surfers” in their homes.

If you are having trouble locating a hotel or an apartment, Paris Webservices’ staff understands our travelers well and personally inspects every hotel and apartment they work with (see here).

Apartments: For more information on apartment rentals, and a list of rental agencies in Paris, see here.

Bed-and-Breakfasts: Though B&Bs (chambres d’hôtes, abbreviated CH) are generally found in smaller towns and rural areas, some are available in Paris. See here for a list of rental agencies that can help.

Home Exchanges: Swapping homes with a Parisian works for some, and HomeExchange.com offers a good variety of exchange choices in Paris. Don’t assume where you live is not interesting to the French (annual membership fee required).

The French eat long and well. Relaxed lunches, three-hour dinners, and endless hours of sitting in outdoor cafés are the norm. Here, celebrated restauranteurs are as famous as great athletes, and mamas hope their babies will grow up to be great chefs. Cafés, cuisine, and wines should become a highlight of any Parisian adventure: It’s sightseeing for your palate. Even if the rest of you is sleeping in a cheap hotel, let your taste buds travel first-class in Paris. (They can go coach in London.)

You can eat well without going broke—but choose carefully: You’re just as likely to blow a small fortune on a mediocre meal as you are to dine wonderfully for €20. Read the information that follows, consider my restaurant suggestions in this book, and you’ll do fine. When restaurant-hunting on your own, choose a spot filled with locals, not the place with the big neon signs boasting, “We Speak English and Accept Credit Cards.” Venturing even a block or two off the main drag can lead to higher-quality food for less than half the price of the tourist-oriented places. Locals eat better at lower-rent locales.

In Paris, lunches are a particularly good value, as most places offer the same quality and similar selections for far less than at dinner. If you’re on a budget or just like going local, try making lunch your main meal, then have a lighter evening meal at a café.

Most hotels offer an optional breakfast, which is usually pleasant and convenient, for about €8-15. A few hotels serve a classic continental breakfast, called petit déjeuner (puh-tee day-zhuh-nay). Traditionally, this consisted of a café au lait, hot chocolate, or tea; a roll with butter and marmalade; and a croissant. But these days most hotels put out a buffet breakfast (cereal, yogurt, fruit, cheese, croissants, juice, and hard-boiled eggs).

If all you want is coffee or tea and a croissant, the corner café offers more atmosphere and is less expensive (though you get more coffee at your hotel). Go local at the café and ask for une tartine (oon tart-een), a baguette slathered with butter or jam. If you crave eggs for breakfast, drop into a café and order une omelette or œufs sur le plat (fried eggs). Some cafés and bakeries offer worthwhile breakfast deals with juice, croissant, and coffee or tea for about €5 (for more on coffee and tea drinks, see here).

To keep it cheap, pick up some fruit at a grocery store and pastries at your favorite boulangerie and have a picnic breakfast, then savor your coffee at a café bar (comptoir) while standing, like the French do. As a less atmospheric alternative, some fast-food places offer cheap breakfasts.

Whether going all out on a perfect French picnic or simply grabbing a sandwich to eat on an atmospheric square, dining with the city as your backdrop can be one of your most memorable meals. For a list of places to picnic in Paris, see here.

Great for lunch or dinner, French picnics can be first-class affairs and adventures in high cuisine. Be daring. Try the smelly cheeses, ugly pâtés, sissy quiches, and minuscule yogurts. Shopkeepers are accustomed to selling small quantities of produce. Get a succulent salad-to-go, and ask for a plastic fork. If you need a knife or corkscrew, borrow one from your hotelier (but don’t picnic in your room, as French hoteliers uniformly detest this). Though drinking wine in public places is taboo in the US, it’s pas de problème in France.

Assembling a Picnic: Visit several small stores to put together a complete meal. Shop early, as many shops close from 12:00 or 13:00 to 15:00 for their lunch break. Say “Bonjour” as you enter, then point to what you want and say, “S’il vous plaît.” For other terminology you might need while shopping, see the sidebar on here.

At the boulangerie (bakery), buy some bread. A baguette usually does the trick, or choose from the many loaves of bread on display: pain aux céréales (whole grain with seeds), pain de campagne (country bread, made with unbleached bread flour), pain complet (wheat bread), or pain de seigle (rye bread). To ask for it sliced, say “Tranché, s’il vous plaît.”

At the pâtisserie (pastry shop, which is often the same place you bought the bread), choose a dessert that’s easy to eat with your hands. My favorites are éclairs (chocolat or café flavored), individual fruit tartes (framboise is raspberry, fraise is strawberry, citron is lemon), and macarons (made of flavored cream sandwiched between two meringues, not coconut cookies like in the US).

At the crémerie or fromagerie (cheese shop), choose a sampling of cheeses. I usually get one hard cheese (like Comté, Cantal, or Beaufort), one soft cow’s milk cheese (like Brie or Camembert), one goat’s milk cheese (anything that says chèvre), and one blue cheese (Roquefort or Bleu d’Auvergne). Goat cheese usually comes in individual portions. For all other large cheeses, point to the cheese you want and ask for une petite tranche (a small slice). The shopkeeper will place a knife on the cheese indicating the size of the slice they are about to cut, then look at you for approval. If you’d like more, say, “Plus.” If you’d like less, say, “Moins.” If it’s just right, say, “C’est bon!”

At the charcuterie or traiteur (for deli items, prepared salads, meats, and pâtés), I like a slice of pâté de campagne (country pâté made of pork) and saucissons sec (dried sausages, some with pepper crust or garlic—you can ask to have it sliced thin like salami). I get a fresh salad, too. Typical options are carottes râpées (shredded carrots in a tangy vinaigrette), salade de betteraves (beets in vinaigrette), and céleri rémoulade (celery root with a mayonnaise sauce). The food comes in takeout boxes, and they may supply a plastic fork.

At a cave à vin you can buy chilled wines that the merchant is usually happy to open and re-cork for you.

At a supermarché, épicerie, or magasin d’alimentation (small grocery store or minimart), you’ll find plastic cutlery and glasses, paper plates, napkins, drinks, chips, and a display of produce. Daily Monop’ stores—offering fresh salads, wraps, fruit drinks, and more at reasonable prices—are convenient one-stop places to assemble a picnic. You’ll see them all over Paris.

Throughout Paris you’ll find plenty of to-go options at crêperies, bakeries, and small stands. Baguette sandwiches, quiches, and pizza-like items are tasty, filling, and budget-friendly (about €4-5).

Sandwiches: Anything served à la provençale has marinated peppers, tomatoes, and eggplant. A sandwich à la italienne is a grilled panino. Here are some common sandwiches:

Fromage (froh-mahzh): Cheese (white on beige).

Jambon beurre (zhahn-bohn bur): Ham and butter (boring for most but a French classic).

Jambon crudités (zhahn-bohn krew-dee-tay): Ham with tomatoes, lettuce, cucumbers, and mayonnaise.

Pain salé (pan sah-lay) or fougasse (foo-gahs): Bread rolled up with salty bits of bacon, cheese, or olives.

Poulet crudités (poo-lay krew-dee-tay): Chicken with tomatoes, lettuce, maybe cucumbers, and always mayonnaise.

Saucisson beurre (saw-see-sohn bur): Thinly sliced sausage and butter.

Thon crudités (tohn krew-dee-tay): Tuna with tomatoes, lettuce, and maybe cucumbers, but definitely mayonnaise.

Quiche: Typical quiches you’ll see at shops and bakeries are lorraine (ham and cheese), fromage (cheese only), aux oignons (with onions), aux poireaux (with leeks—my favorite), aux champignons (with mushrooms), au saumon (salmon), or au thon (tuna).

Crêpes: The quintessentially French thin pancake called a crêpe (rhymes with “step,” not “grape”) is filling, usually inexpensive, and generally quick. Simply place your order at the crêperie window or kiosk, and watch the chef in action. But don’t be surprised if they don’t make a wrapper for you from scratch; at some crêperies, they might premake a stack of wrappers and reheat them when they fill your order.

Crêpes generally are sucrée (sweet) or salée (savory). Technically, a savory crêpe should be made with a heartier buckwheat batter, and is called a galette. However, many cheap and lazy crêperies use the same sweet batter (de froment) for both their sweet-topped and savory-topped crêpes. A socca is a chickpea crêpe.

Standard crêpe toppings include cheese (fromage; usually Swiss-style Gruyère or Emmental), ham (jambon), egg (oeuf), mushrooms (champignons), chocolate, Nutella, jam (confiture), whipped cream (chantilly), apple jam (compote de pommes), chestnut cream (crème de marrons), and Grand Marnier.

To get the most out of dining out in France, slow down. Allow enough time, engage the waiter, show you care about food, and enjoy the experience as much as the food itself.

French waiters probably won’t overwhelm you with friendliness. As their tip is already included in the bill (see “Tipping,” below), there’s less schmoozing than we’re used to at home. Notice how hard they work. They almost never stop. Cozying up to clients (French or foreign) is probably the last thing on their minds. They’re often stuck with client overload, too, because the French rarely hire part-time employees, even to help with peak times. To get a waiter’s attention, try to make meaningful eye contact, which is a signal that you need something. If this doesn’t work, raise your hand and simply say, “S’il vous plaît” (see voo play)—“please.”

This phrase should also work when you want to ask for the check. In French eateries, a waiter will rarely bring you the check unless you request it. For a French person, having the bill dropped off before asking for it is akin to being kicked out—très gauche. But busy travelers are often ready for the check sooner rather than later. If you’re in a hurry, ask for the bill when your server comes to clear your plates or checks in to see if you want dessert or coffee. To request your bill, say, “L’addition, s’il vous plaît.” If you don’t ask now, the wait staff may become scarce as they leave you to digest in peace. (For a list of other restaurant survival phrases, see here.)

Note that all café and restaurant interiors are smoke-free. Today the only smokers you’ll find are at outside tables, which—unfortunately—may be exactly where you want to sit.

For a list of common French dishes that you’ll see on menus, see here. For details on ordering drinks, see here.

Tipping: At cafés and restaurants, a 12-15 percent service charge is always included in the price of what you order (service compris or prix net), but you won’t see it listed on your bill. Unlike in the US, France pays servers a decent wage. Because of this, most locals never tip. If you feel the service was exceptional, tip up to 5 percent extra. If you want the waiter to keep the change when you pay, say “C’est bon” (say bohn), meaning “It’s good.” If you are using a credit card, leave your tip in cash—credit-card receipts don’t even have space to add a tip. Never feel guilty if you don’t leave a tip.

French cafés and brasseries provide user-friendly meals and a relief from sightseeing overload. They’re not necessarily cheaper than many restaurants and bistros, and famous cafés on popular squares can be pricey affairs. Their key advantage is flexibility: They offer long serving hours, and you’re welcome to order just a salad, a sandwich, or a bowl of soup, even for dinner. It’s also fine to split starters and desserts, though not main courses.

Cafés and brasseries usually open by 7:00, but closing hours vary. Unlike restaurants, which open only for dinner and sometimes for lunch, some cafés and all brasseries serve food throughout the day (usually with a limited menu), making them the best option for a late lunch or an early dinner.

Check the price list first, which by law must be posted prominently (if you don’t see one, go elsewhere). There are two sets of prices: You’ll pay more for the same drink if you’re seated at a table (salle) than if you’re seated or standing at the bar or counter (comptoir). (For tips on ordering coffee and tea, see here.)

At a café or a brasserie, if the table is not set, it’s fine to seat yourself and just have a drink. However, if it’s set with a placemat and cutlery, you should ask to be seated and plan to order a meal. If you’re unsure, ask the server before sitting down.

Ordering: A salad, crêpe, quiche, or omelet is a fairly cheap way to fill up. Each can be made with various extras such as ham, cheese, mushrooms, and so on. Omelets come lonely on a plate with a basket of bread.

Sandwiches, generally served day and night, are inexpensive, but most are very plain (boulangeries serve better ones). To get more than a piece of ham (jambon) on a baguette, order a sandwich jambon crudités, which means it’s garnished with veggies. Popular sandwiches are the croque monsieur (grilled ham-and-cheese) and croque madame (monsieur with a fried egg on top).

Salads are typically large and often can be ordered with warm ingredients mixed in, such as melted goat cheese, fried gizzards, or roasted potatoes. One salad is perfect for lunch or a light dinner. See here for a list of classic salads.

The daily special—plat du jour (plah dew zhoor), or just plat is your fast, hearty, and garnished hot plate for about €12-20. At most cafés, feel free to order only entrées (which in French means the starter course); many people find these lighter and more interesting than a main course. A vegetarian can enjoy a tasty, filling meal by ordering two entrées (for more on navigating France with dietary restrictions, see page).

Regardless of what you order, bread is free but almost never comes with butter; to get more bread, just hold up your basket and ask, “Encore, s’il vous plaît?”

Choose restaurants filled with locals. Consider my suggestions and your hotelier’s opinion, but trust your instincts. If a restaurant doesn’t post its prices outside, move along. Refer to my restaurant recommendations to get a sense of what a reasonable meal should cost.

Restaurants open for dinner around 19:00, and small local favorites get crowded after 21:00. To minimize crowds, go early (around 19:30). Last seating at Parisian restaurants is about 22:00 or later. Many restaurants close Sunday and/or Monday.

Tune into the quiet, relaxed pace of French dining. The French don’t do dinner and a movie on date nights; they just do dinner. The table is yours for the night. Notice how quietly French diners speak in restaurants and how this improves your overall experience. Out of consideration for others, speak as softly as the locals.

If a restaurant serves lunch, it generally begins at 12:00 and goes until 14:30, with last orders taken at about 14:00. If you’re hungry when restaurants are closed (late afternoon), go to a boulangerie, brasserie, or café (see previous section). Remember that even the fanciest places have affordable lunch menus (often called formules or plat de midi), allowing you to sample the same gourmet cooking for generally about half the cost of dinner.

Ordering: In French restaurants, you can choose something off the menu (called the carte), or you can order a multicourse, fixed-price meal (confusingly, called a menu). Or, if offered, you can get one of the special dishes of the day (plat du jour). If you ask for un menu (instead of la carte), you’ll get a fixed-price meal.

You’ll have the best selection if you order à la carte (from what we would call the menu). It’s traditional to order an entrée (a starter—not a main dish) and a plat principal (main course). The plats are generally more meat-based, while the entrées usually include veggies. Multiple course meals, while time-consuming (a positive thing in France), create the appropriate balance of veggies to meat. Elaborate meals may also have entremets—tiny dishes served between courses. Wherever you dine, consider the waiter’s recommendations and anything de la maison (of the house), as long as it’s not an organ meat (tripe, rognons, or andouillette).

Two people can split an entrée or a big salad (since small-size dinner salads are usually not offered á la carte) and then each get a plat principal. At restaurants, it’s considered inappropriate for two diners to share one main course. If all you want is a salad or soup, go to a café or brasserie.

Menus, which usually include two or three courses, are generally a good value and will help you pace your meal like the locals. With a three-course menu you’ll get your choice of soup, appetizer, or salad; your choice of three or four main courses with vegetables; plus a cheese course and/or a choice of desserts. It sounds like a lot of food, but portions are smaller in France, and what we cram onto one large plate they spread out over several courses. Wine and other drinks are extra, and certain premium items add a few euros to the price, clearly noted on the menu (supplément or sup.). Most restaurants offer less expensive and less filling two-course menus, sometimes called formules, featuring an entrée et plat, or plat et dessert. Some restaurants (and cafés) offer great-value lunch menus, and many restaurants have a reasonable menu-enfant (kid’s meal).

The fun part of dining in Paris is that you can sample fine cuisine from throughout France. Most restaurants serve dishes from several regions, though some focus on a particular region’s cuisine (see the sidebar for a list of specialty dishes by region). In this book I list restaurants specializing in food from Provence, Burgundy, Alsace, Normandy, Brittany, Dordogne, Languedoc, and the Basque region. You can be a galloping gourmet and try several types of French cuisine without ever leaving the confines of Paris.

General styles of French cooking include haute cuisine (classic, elaborately prepared, multicourse meals); cuisine bourgeoise (the finest-quality home cooking); cuisine des provinces (traditional dishes of specific regions); and nouvelle cuisine (a focus on smaller portions and closer attention to the texture and color of the ingredients). Sauces are a huge part of French cooking. In the early 20th century, the legendary French chef Auguste Escoffier identified five French “mother sauces” from which all others are derived: béchamel (milk-based white sauce), espagnole (veal-based brown sauce), velouté (stock-based white sauce), hollandaise (egg yolk-based white sauce), and tomate (tomato-based red sauce).

The following list of items should help you navigate a typical French menu. Galloping gourmets should bring a menu translator. The most complete (and priciest) menu reader around is A to Z of French Food by G. de Temmerman. The Marling Menu-Master is also good. The Rick Steves’ French Phrase Book & Dictionary, with a menu decoder, works well for most travelers.

Crudités: A mix of raw and lightly cooked fresh vegetables, usually including grated carrots, celery root, tomatoes, and beets, often with a hefty dose of vinaigrette dressing. If you want the dressing on the side, say, “La sauce à côté, s’il vous plaît” (lah sohs ah koh-tay, see voo play).

Escargots: Snails cooked in parsley-garlic butter. You don’t even have to like the snail itself. Just dipping your bread in garlic butter is more than satisfying. Prepared a variety of ways, the classic is à la bourguignonne (served in their shells).

Foie gras: Rich and buttery in consistency—and hefty in price—this pâté is made from the swollen livers of force-fed geese (or ducks, in foie gras de canard). Spread it on bread, and never add mustard. For a real French experience, try this dish with some sweet white wine (often offered by the glass for an additional cost).

Huîtres: Oysters, served raw any month, are particularly popular at Christmas and on New Year’s Eve, when every café seems to have overflowing baskets in their window.

Œuf mayo: A simple hard-boiled egg topped with a dollop of flavorful mayonnaise.

Pâtés and terrines: Slowly cooked ground meat (usually pork, though game, poultry liver, and rabbit are also common) that is highly seasoned and served in slices with mustard and cornichons (little pickles). Pâtés are smoother than the similarly prepared but chunkier terrines.

Soupe à l’oignon: Hot, salty, filling—and hard to find in Paris—French onion soup is a beef broth served with a baked cheese-and-bread crust over the top.

With the exception of a salade mixte (simple green salad, often difficult to find), the French get creative with their salades. Here are some classics:

Salade au chèvre chaud: This mixed green salad is topped with warm goat cheese on small pieces of toast.

Salade aux gésiers: Though it may not sound appetizing, this salad with chicken gizzards (and often slices of duck) is worth a try.

Salade composée: “Composed” of any number of ingredients, this salad might have lardons (bacon), Comté (a Swiss-style cheese), Roquefort (blue cheese), œuf (egg), noix (walnuts), and jambon (ham, generally thinly sliced).

Salade niçoise: A specialty from Nice, this tasty salad usually includes greens topped with green beans, boiled potatoes, tomatoes, anchovies, olives, hard-boiled eggs, and lots of tuna.

Salade paysanne: You’ll usually find potatoes (pommes de terre), walnuts (noix), tomatoes, ham, and egg in this salad.

Duck, lamb, and rabbit are popular in France, and each is prepared in a variety of ways. You’ll also encounter various stew-like dishes that vary by region. The most common regional specialties are described here.

Bœuf bourguignon: A Burgundian specialty, this classy beef stew is cooked slowly in red wine, then served with onions, potatoes, and mushrooms.

Confit de canard: A favorite from the southwest Dordogne region is duck that has been preserved in its own fat, then cooked in its fat, and often served with potatoes (cooked in the same fat). Not for dieters. (Note that magret de canard is sliced duck breast and very different in taste.)

Coq au vin: This Burgundian dish is rooster marinated ever so slowly in red wine, then cooked until it melts in your mouth. It’s served (often family-style) with vegetables.

Daube: Generally made with beef, but sometimes lamb, this is a long and slowly simmered dish, typically paired with noodles or other pasta.

Escalope normande: This specialty of Normandy features turkey or veal in a cream sauce.

Gigot d’agneau: A specialty of Provence, this is a leg of lamb often grilled and served with white beans. The best lamb is pré salé, which means the lamb has been raised in salt-marsh lands (like at Mont St-Michel).

Poulet rôti: Roasted chicken on the bone—French comfort food.

Saumon and truite: You’ll see salmon dishes served in various styles. The salmon usually comes from the North Sea and is always served with sauce, most commonly a sorrel (oseille) sauce. Trout (truite) is also fairly routine on menus.

Steak: Referred to as pavé (thick hunk of prime steak), bavette (skirt steak), faux filet (sirloin), or entrecôte (rib steak), French steak is usually thinner and tougher than American steak and is always served with sauces (au poivre is a pepper sauce, une sauce roquefort is a blue-cheese sauce). Because steak is usually better in North America, I generally avoid it in France (unless the sauce sounds good). You will also see steak haché, which is a lean, gourmet hamburger patty served sans bun. When it’s served as steak haché à cheval, it comes with a fried egg on top.

By American standards, the French undercook meats: Their version of rare, saignant (seh-nyahn), means “bloody” and is close to raw. What they consider medium, à point (ah pwan), is what an American would call rare. Their term for well-done, or bien cuit (bee-yehn kwee), would translate as medium for Americans.

Steak tartare: This wonderfully French dish is for adventurous types only. It’s very lean, raw hamburger served with savory seasonings (usually Tabasco, capers, raw onions, salt, and pepper on the side) and topped with a raw egg yolk. This is not hamburger as we know it, but freshly ground beef.

In France the cheese course is served just before (or instead of) dessert. It not only helps with digestion, it gives you a great opportunity to sample the tasty regional cheeses—and time to finish up your wine. Between cow, goat, and sheep cheeses, there are more than 400 different ones to try in France. Some restaurants will offer a cheese platter, from which you select a few different kinds. A good platter has at least four cheeses: a hard cheese (such as Cantal), a flowery cheese (such as Brie or Camembert), a blue or Roquefort cheese, and a goat cheese.

Those most commonly served in Paris are Brie de Meaux (mild and creamy, from just outside Paris), Camembert (semi-creamy and pungent, from Normandy), chèvre (goat cheese with a sharp taste, usually from the Loire), and Roquefort (strong and blue-veined, from south-central France).

If you’d like to sample several types of cheese from the cheese plate, say, “Un assortiment, s’il vous plaît” (uhn ah-sor-tee-mahn, see voo play). You’ll either be served a selection of several cheeses or choose from a large selection offered on a cheese tray or cart. If you serve yourself from the cheese tray, observe French etiquette and keep the shape of the cheese. It’s best to politely shave off a slice from the side or cut small wedges.

A glass of good red wine complements your cheese course in a heavenly way.

If you order espresso, it will always come after dessert. To have coffee with dessert, ask for “café avec le dessert” (kah-fay ah-vehk luh day-sayr). See the list of coffee terms on here. Here are the types of treats you’ll see:

Baba au rhum: Pound cake drenched in rum, served with whipped cream.

Café gourmand: An assortment of small desserts selected by the restaurant—a great way to sample several desserts and learn your favorite.

Crème brûlée: A rich, creamy, dense, caramelized custard.

Crème caramel: Flan in a caramel sauce.

Fondant au chocolat: A molten chocolate cake with a runny (not totally cooked) center. Also known as moelleux (meh-leh) au chocolat.

Fromage blanc: A light dessert similar to plain yogurt (yet different), served with sugar or herbs.

Glace: Ice cream—typically vanilla, chocolate, or strawberry.

Ile flottante: A light dessert consisting of islands of meringue floating on a pond of custard sauce.

Mousse au chocolat: Chocolate mousse.

Profiteroles: Cream puffs filled with vanilla ice cream, smothered in warm chocolate sauce.

Riz au lait: Rice pudding.

Sorbets: Light, flavorful, and fruity ices, sometimes laced with brandy.

Tartes: Narrow strips of fresh fruit, baked in a crust and served in thin slices (without ice cream).

Tarte tatin: Apple pie like grandma never made, with caramelized apples, cooked upside down, but served upright.

In stores, unrefrigerated soft drinks, bottled water, and beer are one-third the price of cold drinks. Bottled water and boxed fruit juice are the cheapest drinks. Avoid buying drinks to-go at streetside stands; you’ll pay far less in a shop.

In bars and at eateries, be clear when ordering drinks—you can easily pay €9 for an oversized Coke and €14 for a supersized beer at some cafés. When you order a drink, state the size in centiliters (don’t say “small,” “medium,” or “large,” because the waiter might bring a bigger drink than you want). For something small, ask for 25 centilitres (vant-sank sahn-tee-lee-truh; about 8 ounces); for a medium drink, order 33 cl (trahnte-twah; about 12 ounces—a normal can of soda); a large is 50 cl (san-kahnt; about 16 ounces); and a super-size is one liter (lee-truh; about a quart—which is more than I would ever order in France). The ice cubes melted after the last Yankee tour group left.

The French are willing to pay for bottled water with their meal (eau minérale; oh mee-nay-rahl) because they prefer the taste over tap water. Badoit is my favorite carbonated water (l’eau gazeuse; loh gah-zuhz). To get a free pitcher of tap water, ask for une carafe d’eau (oon kah-rahf doh). Otherwise, you may unwittingly buy bottled water.

In France limonade (lee-moh-nahd) is Sprite or 7-Up. For a fun, bright, nonalcoholic drink of 7-Up with mint syrup, order un diabolo menthe (uhn dee-ah-boh-loh mahnt). For 7-Up with fruit syrup, order un diabolo grenadine (think Shirley Temple). Kids love the local orange drink, Orangina, a carbonated orange juice with pulp (though it can be pricey). They also like sirop à l’eau (see-roh ah loh), flavored syrup mixed with bottled water.

For keeping hydrated on the go, hang on to the half-liter mineral-water bottles (sold everywhere for about €1) and refill. Buy juice in cheap liter boxes, then drink some and store the extra in your water bottle. Of course, water quenches your thirst better and cheaper than anything you’ll find in a store or café. I drink tap water throughout France, filling up my bottle in hotel rooms.

The French define various types of espresso drinks by how much milk is added. To the French, milk is a delicate form of nutrition: You need it in the morning, but as the day goes on, too much can upset your digestion. Therefore, the amount of milk that’s added to coffee decreases as the day goes on. A café au lait is exclusively for breakfast time, and a café crème is appropriate through midday. You’re welcome to order a milkier coffee drink later in the day, but don’t be surprised if you get a funny look.

By law, a waiter must give you a glass of tap water with your coffee or tea if you request it; ask for “un verre d’eau, s’il vous plaît” (uhn vayr doh, see voo play).

Here are some common coffee and tea drinks:

Café (kah-fay): Shot of espresso

Café allongé, a.k.a. café longue (kah-fay ah-lohn-zhay; kah-fay lohn): Espresso topped up with hot water—like an Americano

Noisette (nwah-zeht): Espresso with a dollop of milk (best value for adding milk to your coffee)

Café au lait (kah-fay oh lay): Espresso mixed with lots of warm milk (used mostly for coffee made at home; in a café, order café crème)

Café crème (kah-fay krehm): Espresso with a sizable pour of steamed milk (closest thing you’ll get to an American-style latte)

Grand crème (grahn krehm): Double shot of espresso with a bit more steamed milk (and often twice the price)

Décafféiné (day-kah-fee-nay): Decaf—available for any of the above

Thé nature (tay nah-tour): Plain tea

Thé au lait (tay oh lay): Tea with milk

Thé citron (tay see-trohn): Tea with lemon

Infusion (an-few-see-yohn): Herbal tea

Be aware that the legal drinking age is 16 for beer and wine and 18 for the hard stuff—at restaurants it’s normale for wine to be served with dinner to teens.

Wine: Wines are often listed in a separate carte des vins. House wine at the bar is generally cheap and good (about €3-5/glass). At a restaurant, a bottle or carafe of house wine costs €10-20. To order inexpensive wine at a restaurant, ask for table wine in a pitcher (only available when seated and when ordering food), rather than a bottle. Finer restaurants usually offer only bottles of wine.

Here are some important wine terms:

Vin du pays (van duh pay): Table wine

Verre de vin rouge (vehr duh van roozh): Glass of red wine

Verre de vin blanc (vehr duh van blahn): Glass of white wine

Pichet (pee-shay): Pitcher

Demi-pichet (duh-mee pee-shay): Half-carafe

Quart (kar): Quarter-carafe (ideal for one)

Beer: Local bière (bee-ehr) costs about €5 at a restaurant and is cheaper on tap (une pression; oon pres-yohn) than in the bottle (bouteille; boo-teh-ee). France’s better beers are Alsatian; try Kronenbourg or the heavier Pelfort (one of your author’s favorites). Une panaché (oon pah-nah-shay) is a tasty French shandy (beer and lemon soda). Un Monaco is a red drink made with beer, grenadine, and lemonade.

Aperitifs: For a refreshing before-dinner drink, order a kir (pronounced “keer”)—a thumb’s level of crème de cassis (black currant liqueur) topped with white wine. If you like brandy, try a marc (regional brandy, e.g., marc de Bourgogne) or an Armagnac, cognac’s cheaper twin brother. Pastis, the standard southern France aperitif, is a sweet anise (licorice) drink that comes on the rocks with a glass of water. Cut it to taste with lots of water.

Staying connected in Europe gets easier and cheaper every year. The simplest solution is to bring your own device—mobile phone, tablet, or laptop—and use it just as you would at home (following the tips below, such as connecting to free Wi-Fi whenever possible). Another option is to buy a European SIM card for your mobile phone—either your US phone or one you buy in Europe. Or you can travel without a mobile device and use European landlines and computers to connect. Each of these options is described below, and you’ll find even more details at www.ricksteves.com/phoning.

Without an international plan, typical rates from major service providers (AT&T, Verizon, etc.) for using your device abroad are about $1.50/minute for voice calls, 50 cents to send text messages, 5 cents to receive them, and $20 to download one megabyte of data. But at these rates, costs can add up quickly. Here are some budget tips and options.

Use free Wi-Fi whenever possible. Unless you have an unlimited-data plan, you’re best off saving most of your online tasks for Wi-Fi (pronounced wee-fee in French). You can access the Internet, send texts, and even make voice calls over Wi-Fi.

Many cafés (including Starbucks and McDonald’s) have hotspots for customers; look for signs offering it and ask for the Wi-Fi password when you buy something. You’ll also often find Wi-Fi at TIs, city squares, major museums, public-transit hubs, airports, and aboard trains and buses. For more on where to find free Wi-Fi in Paris, see here.

Sign up for an international plan. Most providers offer a global calling plan that cuts the per-minute cost of phone calls and texts, and a flat-fee data plan that includes a certain amount of megabytes. Your normal plan may already include international coverage (T-Mobile’s does).

Before your trip, call your provider or check online to confirm that your phone will work in Europe, and research your provider’s international rates. A day or two before you leave, activate the plan by calling your provider or logging on to your mobile phone account. Remember to cancel your plan (if necessary) when your trip’s over.

Minimize the use of your cellular network. When you can’t find Wi-Fi, you can use your cellular network—convenient but slower and potentially expensive—to connect to the Internet, text, or make voice calls. When you’re done, avoid further charges by manually switching off “data roaming” or “cellular data” (in your device’s Settings menu; if you don’t know how to switch it off, ask your service provider or Google it). Another way to make sure you’re not accidentally using data roaming is to put your device in “airplane” or “flight” mode (which also disables phone calls and texts, as well as data), and then turn on Wi-Fi as needed.

Don’t use your cellular network for bandwidth-gobbling tasks, such as Skyping, downloading apps, and watching YouTube—save these for when you’re on Wi-Fi. Using a navigation app such as Google Maps can take lots of data, so use this sparingly.

Limit automatic updates. By default, your device is constantly checking for a data connection and updating apps. It’s smart to disable these features so they’ll only update when you’re on Wi-Fi, and to change your device’s email settings from “auto-retrieve” to “manual” (or from “push” to “fetch”).

It’s also a good idea to keep track of your data usage. On your device’s menu, look for “cellular data usage” or “mobile data” and reset the counter at the start of your trip.

Use Skype or other calling/messaging apps for cheaper calls and texts. Certain apps let you make voice or video calls or send texts over the Internet for free or cheap. If you’re bringing a tablet or laptop, you can also use them for voice calls and texts. All you have to do is log on to a Wi-Fi network, then contact any of your friends or family members who are also online and signed into the same service. You can make voice and video calls using Skype, Viber, FaceTime, and Google+ Hangouts. If the connection is bad, try making an audio-only call.

You can also make voice calls from your device to telephones worldwide for just a few cents per minute using Skype, Viber, or Hangouts if you prebuy credit.

To text for free over Wi-Fi, try apps like Google+ Hangouts, What’s App, Viber, and Facebook Messenger. Apple’s iMessage connects with other Apple users, but make sure you’re on Wi-Fi to avoid data charges.

This option works well for those who want to make a lot of voice calls at cheap local rates. Either buy a phone in Europe (as little as $40 from mobile-phone shops anywhere), or bring an “unlocked” US phone (check with your carrier about unlocking it). With an unlocked phone, you can replace the original SIM card (the microchip that stores info about the phone) with one that will work with a European provider.

In Europe, buy a European SIM card. Inserted into your phone, this card gives you a European phone number—and European rates. SIM cards are sold at mobile-phone shops, department-store electronics counters, some newsstands, and even at vending machines. Costing about $5-10, they usually include about that much prepaid calling credit, with no contract and no commitment. You can still use your phone’s Wi-Fi function to get online. To get a SIM card that also includes data costs (including roaming), figure on paying $15-30 for one month of data within the country you bought it. This can be cheaper than data roaming through your home provider. To get the best rates, buy a new SIM card whenever you arrive in a new country.

I like to buy SIM cards at a mobile-phone shop where there’s a clerk to help explain the options and brands. Certain brands—including Lebara and Lycamobile, both of which operate in multiple European countries—are reliable and economical. Ask the clerk to help you insert your SIM card, set it up, and show you how to use it. In some countries you’ll be required to register the SIM card with your passport as an antiterrorism measure (which may mean you can’t use the phone for the first hour or two).

When you run out of credit, you can top it up at newsstands, tobacco shops, mobile-phone stores, or many other businesses (look for your SIM card’s logo in the window), or online.

It’s easy to travel in Europe without a mobile device. You can check email or browse websites using public computers and Internet cafés, and make calls from your hotel room and/or public phones.

Phones in your hotel room can be inexpensive for local calls and calls made with cheap international phone cards (carte international), sold at many post offices, newsstands, street kiosks, tobacco shops, and train stations. You’ll either get a prepaid card with a toll-free number and a scratch-to-reveal PIN code, or a code printed on a receipt; to make a call, dial the free (usually 4-digit) access number. If that doesn’t work, dial the toll-free number, follow the prompts, enter the code, then dial your number.

Most hotels charge a fee for placing local and “toll-free” calls, as well as long-distance or international calls—ask for the rates before you dial. Since you’re never charged for receiving calls, it’s better to have someone from the US call you in your room.

It’s always possible to find public computers: at your hotel (many have one in their lobby for guests to use), or at an Internet café or library (ask your hotelier or the TI for the nearest location). If typing on a European keyboard, use the “Alt Gr” key to the right of the space bar to insert the extra symbol that appears on some keys. To type an @ symbol on French keyboards, press the “Alt Gr” and “à/0” key. If you can’t locate a special character, simply copy it from a Web page and paste it into your email message.

You can mail one package per day to yourself worth up to $200 duty-free from Europe to the US (mark it “personal purchases”). If you’re sending a gift to someone, mark it “unsolicited gift.” For details, visit www.cbp.gov and search for “Know Before You Go.”

The French postal service works fine, but for quick transatlantic delivery (in either direction), consider services such as DHL (www.dhl.com). French post offices are referred to as La Poste or sometimes the old-fashioned PTT, for “Post, Telegraph, and Telephone.” Hours vary, though most are open weekdays 8:00-19:00 and Saturday morning 8:00-12:00. Stamps and phone cards are also sold at tabacs. It costs about €1 to mail a postcard to the US. One convenient, if expensive, way to send packages home is to use the post office’s Colissimo XL postage-paid mailing box. It costs €50-90 to ship boxes weighing 5-7 kilos (about 11-15 pounds).

If your trip will cover more of France than just Paris, you may need to take a long-distance train, rent a car, or fly. I give some specifics on trains and flights here. For more detailed information on transportation throughout Europe, including trains, flying, renting a car, and driving, see www.ricksteves.com/transportation.

France’s rail system, called SNCF (short for Société Nationale Chemins de Fer), sets the pace in Europe. Its super TGV (tay zhay vay; train à grande vitesse) system has inspired bullet trains throughout the world. The TGV runs at 170-220 mph. Its rails are fused into one long, continuous track for a faster and smoother ride. The TGV has changed commuting patterns throughout France by putting most of the country within day-trip distance of Paris.

Any staffed train station has schedule information, can make reservations, and can sell tickets for any destination. For more on train travel, see www.ricksteves.com/rail.

Schedules change by season, weekday, and weekend. Verify train times shown in this book—online, check www.bahn.com (Germany’s excellent all-Europe schedule site), or check locally at train stations. The French rail website is www.sncf.com; en.voyages-sncf.com is the English version. It shows ticket prices and sells some tickets online (worth checking if you’re traveling on one or two long-distance trains without a rail pass, as advance-purchase discounts can be a great deal).

Bigger stations may have helpful information agents roaming the station and at Accueil offices or booths. They can answer schedule questions more quickly than staff at the ticket windows. Make use of their help; don’t stand in a ticket line if all you need is a train schedule.

Online: While there’s no deadline to buy any train ticket, the fast, reserved TGV trains get booked up. Reserve well ahead for any TGV you cannot afford to miss. Tickets go on sale 90 to 120 days in advance, with a wide range of prices on any one route. The cheapest tickets sell out early and reservations for rail-pass holders also go particularly fast.

To buy the cheapest advance-discount tickets (50 percent less than full-fare), visit http://en.voyages-sncf.com, three to four months ahead of your travel date. A pop-up window may ask you to choose between being sent to the Rail Europe website or staying on the SNCF page—click “Stay.” Next, choose “Train,” then “TGV.” Under “Book your tickets,” pick your travel dates, and choose “France” as your ticket collection country. Select the cheapest, non-refundable category of tickets, called “Prem’s,” and be sure that it says “TGV” (avoid iDTGV trains—they’re very cheap, but this SNCF subsidiary doesn’t accept PayPal). Choose the eticket delivery option (which you can print at home), and pay using a PayPal account. These low-rate tickets may not be available from Rail Europe or other USA agents.

After the non-refundable rates are sold out, you can buy other fare types on the French site only if you have set up the “Verified by Visa” or “MasterCard SecureCode” program for your US credit card. Otherwise, US customers have to order through a US agency, such as at www.ricksteves.com/rail, which offers both etickets and home delivery, but may not have access to all of the cheapest rates; or Capitaine Train (www.capitainetrain.com), which sells the “Prem’s” fare and iDTGV tickets.